By William Scheck

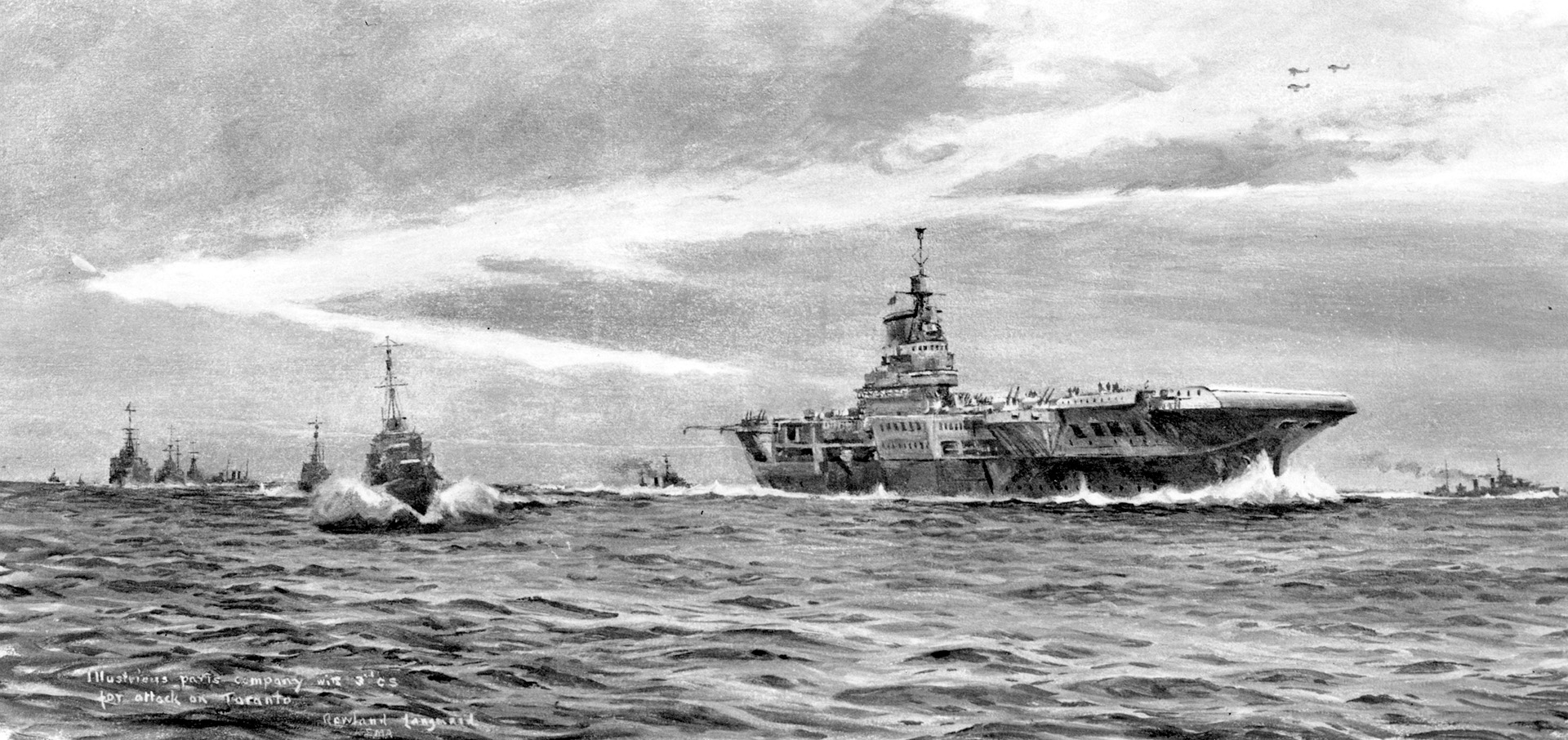

The flight deck of HMS Illustrious had become a very busy place. Aircraft were being raised to the flight deck, aircraft handlers were attending to their tasks, and on the command deck there was an air of anxiety. Illustrious was preparing to launch an unprecedented mission. The final order to carry out a full, airborne, torpedo and dive-bomber attack on the Italian fleet had come down at 7 o’clock that evening. In the deepening twilight, aircraft were being lined up, fully fueled and armed. The air crews, heavily swaddled in their fur-lined “Irving Jackets,” clambered into the open cockpits of their planes. Despite the fact that this was 1940, the flight deck was covered with anachronistic aircraft that resembled veterans of 1918. These were Fairey Swordfish biplanes, Model K4190 Mark II.

The air on the deck was rent by the throaty growl of Pegasus Bristol 1,750 hp engines as the aircraft came to life. Like the biplanes, the engines retained a hallmark of World War I—they were hand-cranked. Bringing one of these engines to life required the vigorous cranking of an inertia starter handle by an engine fitter who needed the strength of Hercules. When the whining reduction gears came up to speed, the pilot then engaged the starting clutch. If he had performed the prestarting drill properly, the Pegasus engine would cough into life. An engine fitter holding a withdrawn crank handle was not amused by a pilot whose engine refused to start on the first try.

In the rear cockpit, which was normally shared by the observer and gunner/wireless telegraphist [WT], there was also a great deal of activity. On normal missions, the observer was engaged in stowing his navigational instruments into their storage slots. These included the Bigsworth Board, which was a rather clumsy wooden frame with attached parallel rulers and dividers and mounted chart upon which calculations would be entered. The gunner/WT checked his single Lewis .303-caliber machine gun, examined his radio connections, and hooked up the nonelectric communication system between crewmen. This consisted of rubber tubes, called Gosport Tubes, which were affixed to the goggled, leather flying helmets of the crew. Despite their primitive appearance, Gosport Tubes were quite effective.

On long-range missions a secondary fuel tank would be installed in the forward seat of the rear cockpit, and an observer performed his own jobs plus that of the WT. Characteristic of the methodology of a Swordfish, the auxiliary fuel tank required a vent on its upper end, protruding from the cockpit. To prevent splashing of fuel during takeoff, a cork would be inserted into this opening. A piece of string attached to the cork was held by the observer, who would open the vent by pulling this cork free once the plane was in level flight. A fuel tank in the observer’s lap complete with cork and string was regarded as “high-tech” in a Swordfish.

Even burdened with a torpedo weighing in at 1,610 lbs., the fabric-covered aircraft vibrated as their engines were run up in the growing darkness. Blue guide lights, mounted on struts running from the upper wing, were turned on to help one plane follow another. In addition, a string of lights running from the upper wing to the forward cockpit—used as a torpedo-aiming aid for the pilot—was checked to see that it was properly activated. In truth, a Swordfish required very little in the way of a preflight mechanical check because the aircraft had retained the simplicity of World War I design. The propeller pitch was fixed, there were no flaps on the wings, there was no power boost to the control surfaces, the massive rudder had no trim tab, and the landing gear was fixed. In short, the Fairey Swordfish was a minimal but robust aircraft—despite its fragile appearance, beneath the vibrating fabric was a substructure of steel tubing. In addition, armor plate protected part of the engine and crew spaces.

With her engines bringing her up to flank speed, HMS Illustrious pointed upwind, the better to give quick lift to her aircraft. As she turned into the wind, she was also turning a corner in tactics and strategy for all navies. Her mission was the first attack by carrier aircraft on an armed and belligerent fleet in its home port. The target was the Regia Marina Italiana (Royal Italian Navy), ensconced in Italy’s largest naval base at Taranto, on the arch of the “Italian boot.” The aircraft carrier—along with its aircraft, was, at this time, a completely untried weapon.

Every navy of the world was aware of the reputed but disputed lethality of aircraft carriers. In every navy there was also a vociferous argument over the relative merits of battleships and aircraft carriers. Seamen, characteristically the most conservative of all military types, and gunships were the soul of the maritime historic tradition. Ships had been performing as gun platforms for hundreds of years and most naval types were very reluctant to abandon a proven system for a concept involving airmen and air-delivered bombs that was regarded as unknown and untried.

At the close of World War I, the U.S. Navy had confined its air operations to the use of seaplanes, generally search aircraft for discovering the enemy, not destroying it. The British had developed a Royal Naval Air Service, which performed similar operations. Moreover naval aviation in the Royal Navy suffered from command control. The entire British air effort, on land or sea, was incorporated in 1917 into a single air service. On ship or shore, whatever could fly belonged to the Royal Air Force. It took years for this decision to be reversed.

Experiments conducted aboard U.S. naval ships established the fact that wheeled aircraft could indeed take off and land on suitably adapted ships. Despite the limitations of aircraft in speed, reliability, utility, and load-carrying ability, experiments continued, albeit on a very restricted basis. In Britain, in the early 1920s, the political clout of the Royal Navy was potent enough to recover naval aviation, despite the expanding hegemony of the Royal Air Force.

Then the Royal Navy struggled to an early entry in the arena of naval aviation. The liner Argus, converted into an aircraft carrier with a minimal flight deck, joined the fleet. The planning for Argus anticipated the use of bombers flying directly off and onto its flight deck. Even earlier, in 1917, the British Admiralty bought back the battleship Almirante Cochrane, still on the ways, from the Chilean Navy. She was converted into a primitive aircraft carrier and began her career as HMS Eagle. The major limitation in naval aviation in all countries was the performance, or lack thereof, of available aircraft.

In the U.S. Navy there was only sporadic and constricted interest in the use of an aircraft carrier as an integral part of the fleet. In Japan, there began to be a growing interest in aircraft in naval operations, which developed into a three-way conflict between the battleship adherents, naval aircraft enthusiasts, and the army, which was at loggerheads with both of the naval factions. It was accepted by almost all that battleships and other well-armored naval vessels were immune from attacks mounted from the air.

But this doctrine was checked by tests held off the coast of Virginia, conceived and conducted by Brig. Gen. William Mitchell of the U.S. Air Service. Mitchell had been beating the drum for a test by his continual allegation that his aircraft were capable of destroying any ship afloat. The interservice rivalry in the United States escalated, and ultimately the navy, by some ill-advised statements, painted itself into a corner and testing was scheduled, albeit reluctantly, in 1921.

Inconclusive trials were initially held using American ships as the targets and employing dummy bombs. The disputed results practically demanded a series of more objective tests. The second time around the targets were former German naval ships with a reputation for durability; these would be subjected to live explosives. Now the ball was in Mitchell’s court. The prime target was to be the former German Ostfriesland. Mitchell took no chances and armed his MB-2 bombers with 2,000-lb. bombs. This was pushing the envelope for the aircraft but lesser bomb weight might not be able to validate Mitchell’s claims.

At noon, on July 21, 1921, the bombers arrived with their massive 2,000-lb. bombs. A direct hit was not really necessary. Explosions of this size, close to a vessel, will wreak serious damage due to the water-hammer effect generated by the incompressibility of fluids. A series of near misses did the trick and Ostfriesland sank beneath the waves before the now significantly silent observers, many of whom were high naval officers. Also attending: then Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The demonstration by Mitchell’s minimal bomber force became the object of deep study in Britain and Japan. But in the United States there was still very little movement toward developing a potent naval air force and even less toward the construction of an aircraft carrier. Then the U.S. Navy made a tentative move toward acquiring an aircraft carrier. Congress was stingy and funds were tight. There could be no aircraft carrier built from scratch, so adherents turned to the collier Jupiter, built in 1912. She had her cargo-handling gear removed and a flight deck installed.

Renamed the USS Langley, this former collier could perform to a limited degree. Aircraft could indeed take off and land on her restricted flight deck and an elevator provided access to the hangar deck. But soon another problem arose as aircraft performance improved. Newer aircraft had higher take-off and landing speeds, which required a concomitant higher speed for the ship. Langley was entirely too slow for her expanding mission and was relegated to the status of a seaplane tender.

On July 22, 1931 the keel was laid for the first U.S. Navy ship to be built as an aircraft carrier. She was the USS Ranger, launched on June 4, 1934. Ranger was a major commitment to naval aviation. She required a crew of 2,000 men, had a waterline length of 728 feet, and carried up to 86 aircraft. She was protected by one inch of armor under the teak decking on her flight deck and had a width of 80 feet, which permitted her to transit the Panama Canal.

The Royal Navy by this time also was building aircraft carriers, although they were experimental in nature and had been converted from liners or other naval vessels. But in 1937 the keel was laid for HMS Illustrious, the first British carrier of modern design. Launched in April 1939, she displaced 23,000 tons, far exceeding the USS Ranger’s 14,000 tons. In addition, Illustrious had 3.5 inches of flight deck armor as well as 4.5 inches of side armor. Despite her much larger size, however, she could carry only 36 aircraft because of her weight and other design limitations.

In 1921 the Japanese navy had converted a merchant ship hull to make the aircraft carrier Kaga, with a 26,000-ton displacement. In 1925, the Akagi, also with a 26,000-ton displacement, joined the fleet. Naval aviation was moving along rapidly in Japan, and the passage of their Third Fleet Replacement Law in the 1920s authorized four major carriers to be constructed. By the outbreak of World War II the Japanese Navy boasted 13 fleet aircraft carriers, to the Royal Navy’s 11 and America’s eight (which included the questionable Langley).

Even the Germans were interested in naval aviation. In 1936 they began to build the Flugzeugetrager Graf Zeppelin (aircraft carrier “Count Zeppelin”), the first aircraft carrier to fly the Nazi swastika flag. Launched on December 8, 1938 she was moved to her fitting-out dock. Germany, with limited naval expertise and even less in naval aviation, never brought this ship to active status. Through internal bureaucratic warfare and interservice rivalry, the ship that could have been on station with the Bismarck during her foray into the Atlantic languished in her fitting-out berth. Having an aircraft carrier as a consort to Bismarck might very well have changed the outcome of her mortal engagement with the Royal Navy in May 1941.

Circumstances allowed the British to take the first decisive move in employing naval aviation. The situation in the Mediterranean in 1940 taxed the British fleet heavily. The Italian Navy was a major player in what Premier Mussolini referred to in his speeches as “Mare Nostrum” (Our Sea). The Italian fleet, though somewhat dated, was potentially a very dangerous antagonist. British convoys, heading for Egypt and the Suez Canal, were constantly menaced by Italian ships based at Taranto.

This Italian port had been a naval outpost since the days of Imperial Rome. Located at the instep of the “Italian boot,” it protected Sicily and the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian coasts, menaced the vital island of Malta, and threatened all shipping lanes. With a “fleet in being” of this lethality, it was clear to the British that the Italian Navy had to be dealt with. The Italian Navy had been built in the same manner as the German and Japanese fleets, that is, essentially for coastal defense and not for far-ranging, high-sea patrolling. In fact, crews of Italian ships did not stay aboard their ships during the long periods they were in their home port. Italian seamen and most officers were berthed either on depot ships or in shore-station barracks. The Italian fleet displayed an understandable reluctance to come to grips with the lethal and aggressive Royal Navy.

At Taranto were inner and outer harbors, the Mar Grande and Mar Piccola. With narrow, easily defended entrances, each was protected by coastal-defense artillery that would make it suicidal to attempt a naval surface attack. British Admiral of the Fleet Sir Andrew Cunningham’s only option was to mount an attack with an untried weapon on targets that were defended and might possibly be warned, manned, and ready for action, all in a distant location. The attack force that would be going against the Italian fleet in its home port consisted of only 21 planes: 11 carrying torpedoes, eight loaded with six 250-lb. armor-piercing bombs, and two assigned as pathfinders, carrying a supply of parachute flares. The Swordfish’s lack of defense capability demanded that this be a nocturnal excursion.

Originally planned for October 21 to celebrate Trafalgar Day, a fire aboard Illustrious on the hangar deck mandated a postponement. In addition, a fuel-contamination problem aboard HMS Eagle changed the plans again. Aircraft were flown from Eagle to Illustrious and now the entire effort was to be mounted from one ship. None of this particularly slowed Admiral Cunningham. He had a Nelsonian streak in his temperament, the urge to close with the enemy, even if he were, unlike Nelson, using his aircraft rather than his ships of the line.

The Italian fleet, in a defensive move, had resorted to sowing mines from the shoreline to the 200-fathom line. The Royal Navy’s draft of Mediterranean Fleet Tactical Instructions stated in one paragraph, “If the enemy fleet is damaged and retires, the British fleet is to pursue to the 200-fathom line.” Cunningham, in his review of this document, added, “until the enemy is sunk. Where the enemy fleet can go, we can follow.” Cunningham knew that a continuation of the present stalemate was unacceptable.

The attack on the ships at Taranto was rescheduled for November 11, 1940. Cunningham was uneasy about his paucity of assets and sketchy knowledge of how vulnerable the target might or might not be. The only experience regarding an air attack on an armed naval ship was confined to the December 1937 sinking of the USS Panay by Japanese aircraft. That attack had taken place on the Yangtze River and Panay was an unarmored gunboat. She had been attacked by dive-bombers and level bombers of the Japanese Naval Air Force. She had remained afloat less than 20 minutes.

The Japanese speedily paid reparations to the United States. They offered some garbled stories about mistaking the Panay for a Chinese naval ship, unlikely because the Chinese Navy had no ships of any type in the area. The explanation circulating in high levels was that the attack was an experiment of the capability of naval aircraft, ordered by Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, a rising star of the Japanese Navy and the standard-bearer of the aircraft faction. The Panay “incident” may very well have been a practical demonstration to settle the difference of opinion in the Japanese Navy between the battleship adherents and the growing group of aviation enthusiasts, led by Yamamoto.

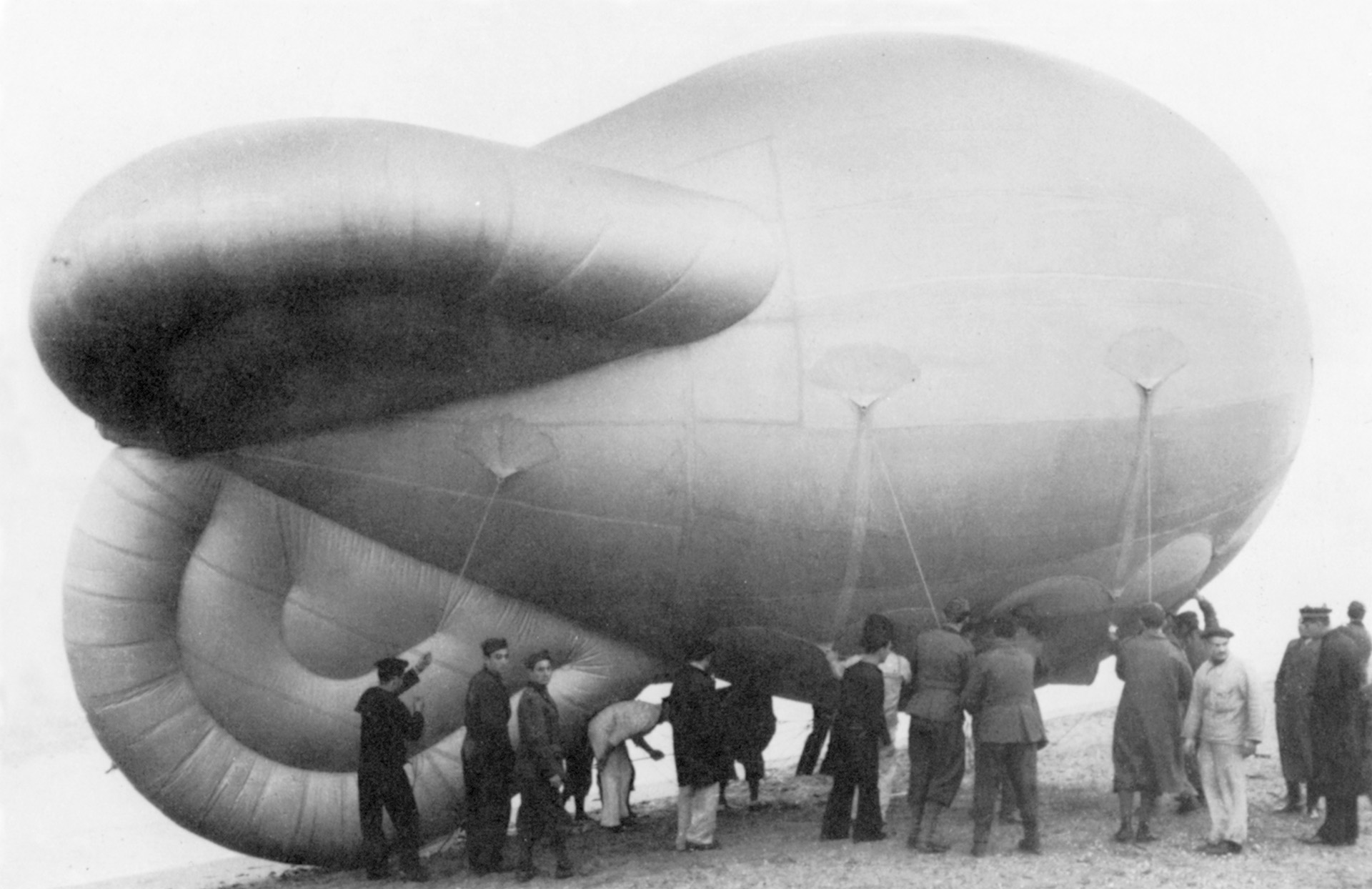

But back to the Mediterranean. The meticulous intelligence work for which the British were noted began to tell. A reconnaissance flight out of Malta garnered photographs of Taranto that showed anchorages, torpedo-net placement, and locations of barrage balloons. Copies of these photos were brought aboard Illustrious, and an elaborate sand table was constructed for study. The crewmen scheduled for the foray, now named Operation Judgment, were rigorously instructed on the layout of their targets. With only 21 aircraft participating, there was little if any margin for error.

November 11 arrived. Aboard Illustrious, at 8:30 pm, the first wave of 13 planes, led by Lt. Cmdr. Williamson, began to take off. With the aircraft carrier heading into the wind, a Swordfish required little in the way of a deck run to get into the air. This was fortunate because the forward vision from the pilot’s seat in a Swordfish was limited. With its nose angled up by the tall landing gear, the pilot kept his forward motion in a straight line by observing how close his wing tip was to the edge of the flight deck. With a wingspan of 45.5 feet, he had to judge this distance carefully.

As the second wave was getting lined, one of the aircraft sustained damage to the fabric of its lower wing. She was speedily taken below and, with her pilot, Lieutenant J.W. Cifford, RN, goading the repair crew, she was speedily returned to the flight deck with the damage rectified. Although her take- off was late, holding back 5 percent of the strike force on account of tardiness was not acceptable. Illustrious was at this time some 170 miles southwest of Taranto.

At the Italian port, all was quiet both in town and aboard ship. This was November 11, the anniversary of Italy’s participation in the victory of 1918. Traditionally, this date was celebrated with fireworks. This year, it was different—the Italian government thought it might be unseemly to hold a fireworks display celebrating its victory over a former enemy who was now an ally. The crews were engaged in their customary recreational activities ashore, but they seemed to hold an air of disappointment over the lack of a celebratory fireworks display. They were about to get one of a different sort.

The Fairey Swordfish, with its engine going flat out, could reach a top speed of 137 mph. But carrying an externally mounted torpedo , it was almost at its maximum load and could barely reach 120 mph. Allowing for headwinds, covering the 170 miles to target would take the best part of two hours. That put the arrival time at about 10 pm, the height of the customarily late Italian dinner hour.

The first aircraft to arrive were the pathfinders droning in from the west at an altitude of 5,000 feet. They tossed out their flares, which made a mild popping sound. Then the flares’ brilliant magnesium light turned night into day as they drifted down over the harbor beneath their small parachutes. The brilliant light cast by the flares initially transfixed the Italians; they were astonished into immobility.

With tremendously fortunate timing, the first torpedo plane arrived at the same time the first flare was ignited. Following one behind the other were the remainder of the first wave—it was too dangerous to attempt formation flying at night, and in any event the dearth of defensive armament made formation flying for Swordfishes superfluous. As the first wave came droning in, each plane maneuvered for its torpedo run. In the bright light of the flares, the pilots were able to discern the predicted locations of the ships and also the cables dangling from the barrage balloons.

The Italians believed they had adequately protected their ships with torpedo nets that hung down to the level of the ships’ keels. They were in for a surprise; the British torpedoes had been altered to compensate for this defense. They were set to run below the keels of the target ships and, thanks to internal devices called Duplex Pistols that could detect the massive steel hulls, explode directly beneath.

Each Swordfish in turn lined up on a target and descended to torpedo-dropping height. Because of their moderate speed, there was little chance of fouling a torpedo setting when the explosive cylinder hit the water’s surface. With its torpedo on its way, each aircraft—significantly lightened—turned and rose to make its escape. Three battleships, the Conte de Cavour, Caio Duilo, and Littorio, were hit by torpedoes with devastating results. The Conte de Cavour sank to the shallow bottom of the harbor, and the other two were severely damaged.

The second wave then arrived and moved to the attack. Some of the planes in this wave were equipped as dive-bombers and acted as such. A Swordfish, in fact, was a tractable dive-bomber. Unlike most dive-bombers, it was not necessary to throttle back the Swordfish’s engine during the dive. Since the plane did not require dive brakes or a pull-out mechanism—on account of an aerodynamic profile cluttered with struts, wires, landing gear, and so forth—it never exceeded a graceful dive speed. As a matter of fact, a pilot had to bring the engine up to full rpm when going into the dive in order to acquire a reasonable speed. After releasing the bomb load, the pilot then throttled down and the Swordfish would begin to lose speed, permitting a gentle pull out.

That night the British dive-bombers were murderously effective. Two cruisers were badly mauled, two auxiliaries were sunk outright, and the fuel tank farm and repair depot sheds were savaged.

Lieutenant Charles Lamb, piloting one of the pathfinder aircraft, had to stooge about over the harbor for almost a half-hour, periodically dropping his flares. It was no patsy assignment, however, with the antiaircraft fire providing an impressive display of pyrotechnics. Lieutanant Lamb later stated that crouching down behind the canvas and leather in his cockpit was one of the most anxious periods of his career.

Antiaircraft fire had been sporadic at the outset of the attack but began to grow as the situation developed. With many of their crews in town, antiaircraft weapons aboard the ships began to respond but only with scratch crews. In addition, the antiaircraft crews had trouble tracking the Swordfish in the fading flare light. The Italians had no radar apparatus and relied on sound-ranging equipment.

Nevertheless, antiaircraft shells exploded and brightened the sky. In some outlying areas people believed a celebratory fireworks display had been set off despite the official ban. But this was no fanfare. Many of the shells fired had not had their fuses cut properly and fell back on the town to explode. The oil tank farm burned and the fire brigade was badly taxed. With crewmen running about trying to return to their ships, some of which were no longer serviceable, the town was a mass of confusion.

Throughout the attack the Italian gunners had problems directing fire at the torpedo planes. The Swordfish, at almost sea level, forced the gunners to take exquisite care to ensure that shells missing the enemy planes would not strike the ships scattered about the harbor. Many batteries tended to concentrate on the flares lighting up the scene. But the flares had a 1,000-foot drop delay before lighting. Apparently, some gunners thought the flares were very close to the aircraft. Firing at the flares, hardly a worthwhile target, was a total waste of ammunition. Thus the Italian gunnery was poorly directed and ineffectively operated; they did not down more than two of 21 elderly aircraft that were fairly well illuminated. The Italians said later they fired 13,489 high-angle antiaircraft shells at the attacking planes as they waltzed around in the brilliant light. They also fired l,750 4-inch shells and 7,000 3-inch shells at the Swordfish. It was a staggering expenditure of ammunition.

The pathfinder planes carried six 250-lb. bombs as well as flares. Lieutanant Lamb, upon completing his illumination duties, turned his attention to the oil tank farm. This target had already been punished, but Lamb’s bombs were also on target and exploded the blazing tanks.

The port now lighted by burning ships and oil tanks and fires in town, the 19 surviving Swordfish biplanes began to reassemble and head for home. Three British crewmen from the downed planes were taken prisoner; the fourth crewman had been killed. Other than these casualties, it was a near-perfect coup. The surviving planes showed little flak damage, and the Italian Navy was given a severe reversal.

In fact, the Royal Navy had greatly alleviated the surface menace of the Italian fleet. Not only had they sunk ships and damaged others, but they forced the Italians to recognize that Taranto was not safe for their fleet. They would have to move it to a more secure base northward—to Naples—but by doing so would be even less of a menace to British naval operations.

The fight at Taranto made front-page news. But arguments persisted over whether or not the air strike there had been a fluke. In The New York Times of November 15, 1940, U.S. Rear Admiral Clark H. Woodward, commandant of the Third Naval District, wrote that he “still held emphatically to the opinion that no battleships, old or new, of any navy, in active service, have ever been destroyed by aerial bomb.” Like many other high naval officials, Woodward was unable to believe what had taken place.

But in many high places the capability of naval aviation began to be appreciated. Those with rigid beliefs in the innate superiority of battleships who had witnessed the Mitchell tests of 1921 now began to rethink their opinions. President Roosevelt, who had always been a battleship adherent, was astute enough to come around. The flares that had lit up a harbor at Taranto began to light up naval minds around the world.

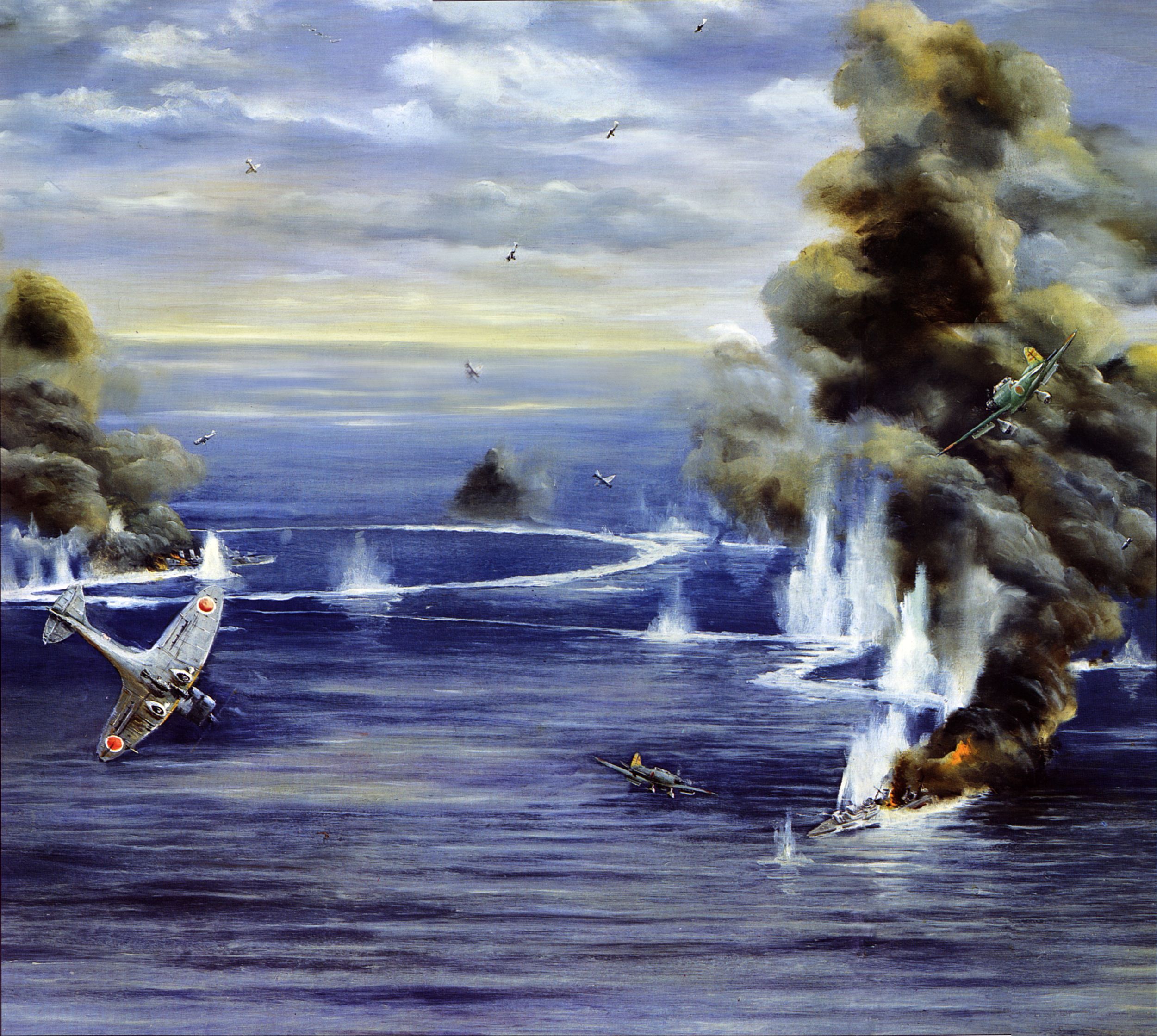

In Japan, Yamamoto saw the Taranto raid as a validation of his theories and an even greater confirmation of his plan for a war against the United States. His planning was based on a novel, published in 1925 and written by renowned naval expert Hector Bywater. This best-seller detailed a war between Japan and the United States that Yamamoto slavishly followed in laying out his plans for the coming conflict.

Fortunately, in the United States, Admiral Woodward’s view began to lose favor and naval air strength grew. As for the British, they had already learned their lesson.

The Japanese, of course, took careful note of all that had happened at Taranto. But they failed to appreciate one aspect of the British triumph. The Royal Navy had taken the trouble to destroy the fuel reserves and repair facilities at the naval base. In the following year at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese attack force commander, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, refused to mount a third-wave attack to deal with the untouched U.S. fuel supplies and repair facilities.

This lack of foresight by Nagumo made Pearl Harbor much less than the victory it was thought to be. Like General George McClellan of the U.S. Army in 1861-1862, Nagumo was reluctant to follow up an advantage to create a decisive victory. The failure to destroy the ancillary facilities at Pearl Harbor made it possible for salvage work to begin immediately. Of all the major ships sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor, all but two had been returned to service within 18 months. USS Utah, an obsolescent ship being used as a target ship, was scrapped. The only other ship that never went back to sea still remains on station as a monument: the USS Arizona.

Taranto had a lesson for everyone, whether fully appreciated at the time or not. But one message could hardly be ignored: The balance of power at sea was slipping away from battleships toward the aircraft carriers and their mobile, lethal aircraft.

William Scheck served in the U.S. Maritime Service, U.S. Army, and Air National Guard, retiring as a Lieutenant Colonel. As a civilian he worked with the U.S. Treasury Department and as an investigator for the U.S. Congress. He has written for numerous magazines dealing with military history.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments