By Michael P. Slater

From an altitude of 30,000 feet, the swift Japanese reconnaissance aircraft flew high over Saipan and Tinian, photographing the brisk and extensive engineering effort under way on the American airfields far below.

Conditions Worsen For Imperial Japan

After completing its mission, the plane evaded fighter interception as it reversed course on a heading due north for the return trip to its airfield on Iwo Jima. Three hours later the reconnaissance plane touched down on one of the battered, but still operational, airfields on the bleak, volcanic island. During their debriefing the crew confirmed Imperial General Headquarters’ grim intelligence estimate. The Americans were expanding the runways and dispersal areas on the major airfields in the Marianas—on Saipan, Tinian, and probably Guam—in preparation for the imminent arrival of giant Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers.

It was September 1944, and Imperial General Headquarters was clearly worried. A few months earlier, on the morning of June 15, 1944, hundreds of armored amphibious tractors had crawled over the reef under heavy defensive fire to disgorge the men of the 2nd and 4th Marine Divisions onto the fire-swept beaches of Saipan. Later that evening, as the fighting raged on Saipan, far away in distant China, the first of 68 U.S. Army Air Force B-29s from the 58th Bombardment Wing began to roll down the runway to commence the first air attack on Japan since the Doolittle Raid more than two years before.

A Psychological Blow To Japanese

As the Marines on Saipan repulsed a series of ferocious Japanese counterattacks, the fleet of silver B-29s, reduced in number through mechanical attrition and operational loss to 48 planes, raided the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yawata on Kyushu at altitudes ranging from 8,000 to 21,000 feet through bursting flak and probing searchlight beams.

Situated on the northwestern corner of the island of Kyushu, Yawata lay at the extreme limit of the B-29 bomber’s range. The damage inflicted on the target did not prevent the Imperial Iron and Steel Works from continuing to produce steel for the Empire’s war machine, but the air raid did deal a serious psychological blow to Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo. Until the B-29 bombardiers toggled their bomb loads over Yawata, physical distance had spared the Home Islands from protracted aerial assault. One small kernel of comfort remained after this raid. From their forward operating bases in China, the B-29s were unable to strike Tokyo and other major Japanese industrial centers on the island of Honshu. With the American invasion and conquest of the Marianas, however, the Superfortress was brought within range of Tokyo, the capital of Imperial Japan.

Low-Flying B-29s Provide Easy Targets

The Imperial Army and Navy air forces were ill prepared in terms of numbers of modern fighters and skilled pilots to combat the swift B-29 bomber formations when they appeared in the skies over Manchuria and Japan. The B-29 carried a larger bomb load farther, faster, and at a higher altitude than any other bomber in the world. To conserve fuel during the long-range missions mounted from bases in China, the bombers often had to fly below their optimum operational ceiling of 30,000 feet. This handicap aided the Japanese defenses, particularly during the XX Bomber Command’s daylight missions over Kyushu, which resulted in higher than expected bomber losses from fighter interception and antiaircraft fire.

On August 19, 1944, for example, during a daylight mission to Yawata, enemy action accounted for five B-29s shot down. The B-29 gunners claimed 17 enemy fighters shot down, demonstrating that the Japanese fighter pilots who fought the fast four-engine silver bombers, with their multiple machine-gun turrets and automated fire control systems, faced a most formidable foe. Combat experience over Manchuria soon demonstrated the inability of early-model Japanese fighters, such as the Imperial Army’s Ki-43 Hayabusa and Ki-44 Shoki, to climb to 30,000 feet and engage the heavily armed bombers on equal terms. On September 26, 1944, during a B-29 raid against the Anshan Steel Works in Manchuria, the B-29s claimed 11 defending Ki-44s shot down and nine probables without losing a single bomber.

Challenging Bombers That Required High-Skilled Pilots

As few Japanese fighter models flew fast enough above 20,000 feet to overtake the bombers in a chase, positioning the fighters at the correct altitude in front of the bomber formations proved the key to combating the B-29s, but this required an efficient air defense system with modern radar and sophisticated fighter direction capabilities. These were only two of the many deficiencies in the Japanese armed forces that the B-29s exposed during raids over Kyushu and Manchuria. Once engaged with the bomber formations, only the latest models of Japanese fighters armed with automatic cannon stood a chance in clawing a B-29 from the sky using conventional tactics.

Head-on firing passes pressed to within 250 meters of the bombers proved the most effective method of fighting the B-29s, but pulling this off at closing speeds in excess of 600 miles per hour took proper positioning of the fighters and extremely adept pilots. Years of war, however, had taken their toll and many of the best pilots had already perished. The novice pilots of the air defense squadrons guarding Japan often experienced great difficulty taming the newer, faster, and more temperamental fighters such as the Army’s Ki-61 Hien and the Navy’s J2M2 Raiden. Most of these eager young men lacked the piloting and gunnery skills to shoot down the B-29s.

Orders are Orders: The ‘Special Duty Attack Unit’

Losses in defending fighters were severe. One consequence was that even skilled Japanese pilots often resorted to ramming tactics over Japan. As for the antiaircraft guns defending Japanese targets, few possessed the range and modern fire control systems necessary to engage the high-flying and extremely fast bomber formations effectively.

On July 20, 1944, the same day a German officer placed a bomb under Adolf Hitler’s map table in East Prussia and two weeks after the garrison on Saipan had mounted its final and futile Banzai charge, Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo issued orders for the Army and Navy to organize provisional Special Duty Attack Units for deployment against the B-29 bases, which were expected to become operational in the Marianas. The purpose of the Special Duty Attack Units was to prevent B-29 raids over Japan. Aviation units selected for this task were expected to fly 1,500 miles and attack “with armor piercing shells enemy planes on the ground.” Having incurred severe losses in planes and aircrews during the first half of 1944, the Imperial Navy and Army had few remaining aviation combat formations to conduct this difficult task.

Orders were orders, however, and planning commenced to implement the Special Duty Attack Unit concept. The first hurdle was geographical. While the United States produced the magnificent B-29 bomber capable of flying round trip with a heavy bomb load from the Marianas to Tokyo, Japan was unable to match this capability with a comparable aircraft. As a consequence, Japanese aircraft assigned to the Special Duty Attack Units would have to refuel at Iwo Jima, 700 miles south of Tokyo, before flying on to strike targets in the Marianas, 600 miles farther south.

Japanese Fail To Unite Army-Navy Air Operations

The three airfields constructed on Iwo Jima were all under the operational control of the Imperial Navy’s 27th Air Flotilla. This aviation command element was assigned responsibility for servicing the aircraft transiting through the island. Chidori Airfield on Iwo Jima, also referred to as Airfield Number One, had the only runway long enough to accommodate the twin-engine bombers selected to execute the bombing missions. Fuel and bombs were shipped on coastal freighters and fishing boats and stored at Chidori in anticipation of an execute order to conduct the raids.

Imperial General Headquarters repeated the same mistake that had doomed earlier Japanese operations when it failed to create a joint Army-Navy headquarters to provide command and control for the Special Duty Attack Units. This error would play a key role in hindering the effectiveness of the strike operations. Each service controlled its respective aircraft through separate headquarters. The intent to fight a decisive battle when the Americans mounted their next major offensive compounded the problem of fielding aviation forces for the Special Duty Attack Units. The Imperial Army and Navy viewed husbanding aviation forces to fight a decisive battle for the fate of the Empire with favor. Employing a handful of planes to bomb airfields in the Marianas failed to spark the same level of interest or enthusiasm.

Devising a Defensive Plan Against The Americans

After the fall of Saipan, four contingency defensive plans to confront the next American offensive were devised. Sho 1 was formulated for the defense of the Philippines, Sho 2 for the defense of the Nansei Islands and Formosa, Sho 3 for the defense of Japan proper excluding Hokkaido, and Sho 4 for the defense of Hokkaido and the Kuriles Islands. An American advance on Formosa was viewed as the most likely and dangerous enemy course of action, so Sho 2 received paramount attention to the detriment of the other contingency plans. In contrast to the numerous Sho plans, the Special Duty Attack Units concept was not afforded the dignity of an operations plan.

In anticipation of having to execute Sho 2, the Navy’s 2nd Air Fleet and Air Training Army Headquarters were co-located at Kanoya Airfield on Kyushu, closer to the anticipated scene of an enemy offensive action and far removed geographically and psychologically from the handful of Special Duty Attack Units assigned a role in the Marianas strike operations. While the Air Training Army Headquarters was assigned responsibility for training and providing Army aviation combat assets for the Special Duty Attack Units, it is unclear which numbered naval air fleet headquarters received this responsibility.

Due to its geographic location and focus on planning for Sho 2, the 2nd Air Fleet at Kanoya probably had no role in the Marianas strike operations. In the event Sho 3 was activated, the 3rd Air Fleet was assigned primary responsibility for the aerial defense of mainland Japan, other than Kyushu, and it may have received responsibility for planning naval air force participation in the Special Duty Attack Units. In October 1944, however, the 3rd Air Fleet was transferred to Formosa, and it played no role in the subsequent Marianas strike operations.

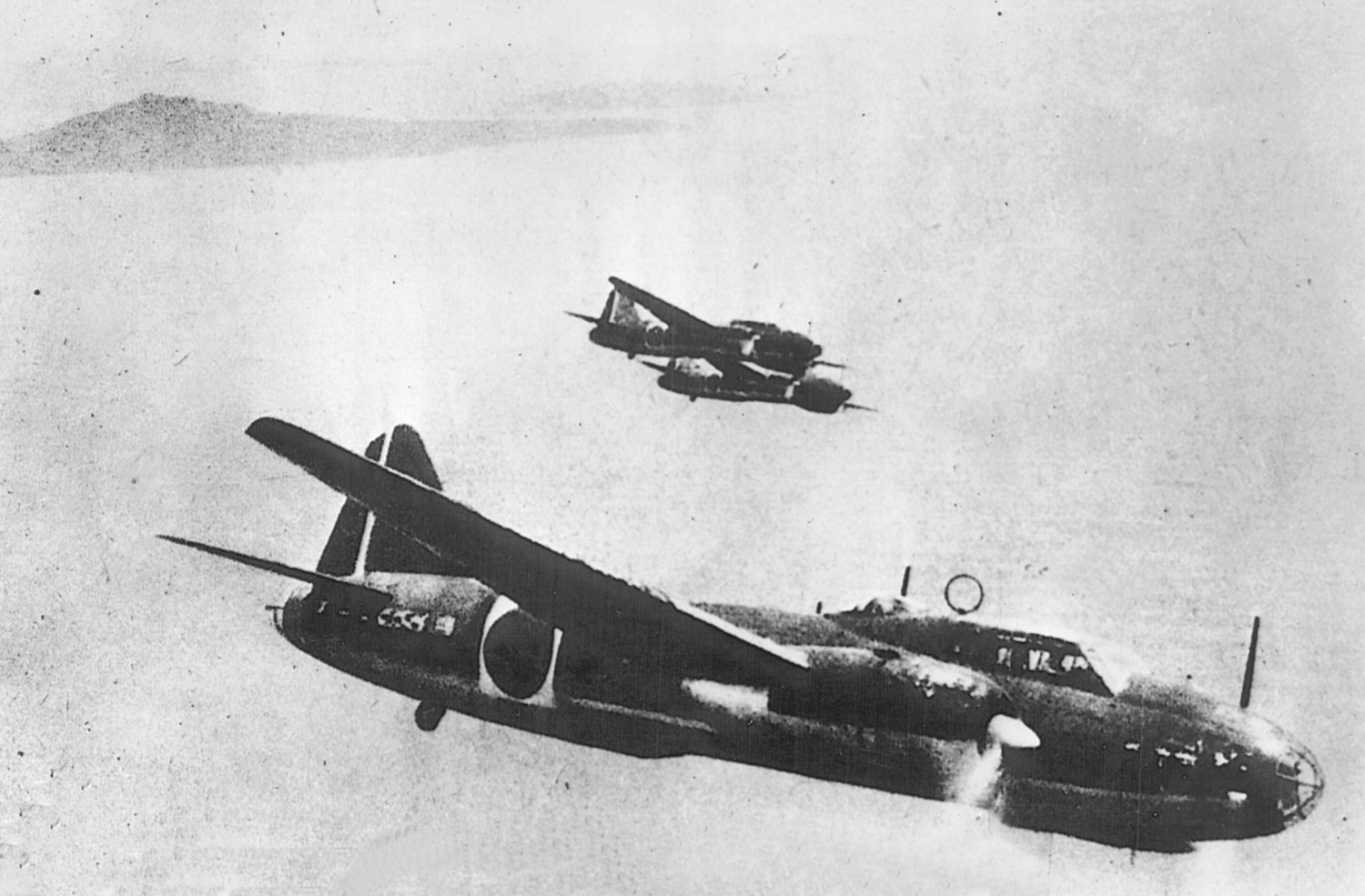

Unimpressive Improvements In The New Bomber

The most important naval aviation bomber unit to participate in the Special Duty Attack Units against the Marianas was (Kogeki) Hikotai 703, or (Attack) Squadron 703, equipped with late-model Type 1 Land-based Attack Aircraft G4M2A, or in Japanese the rikujo Kogeki-ki, or Rikko for short. This aircraft is more commonly referred to today by its Allied codename, Betty. The G4M2A was an improved variant of the original twin-engine bomber.

One important improvement on this aircraft variant was the addition of more powerful 1,850-hp engines with four-bladed propellers. Armament was upgraded as well, with a 20mm cannon in a power-rotated turret replacing the nearly useless handheld 7.7mm machine gun in the dorsal position. Other modifications included an increased number and caliber of defensive machine guns, the installation of a modicum of protection for the vulnerable fuel tanks, and a redesigned wing. Yet even with these modifications, the G4M2A remained extremely vulnerable to enemy fire, particularly machine-gun incendiary and tracer rounds hitting the fuel tanks in the wings. As early as 1942, sarcastic Rikko crews had nicknamed their aircraft a “one shot lighter” in reference to its cigar-shaped fuselage and the plane’s disturbing tendency to explode in flames when struck by enemy fire.

Japanese Rely on the Darkness For Their Aerial Operations

Even after orders were issued to establish Special Duty Attack Units, the Imperial Navy concentrated on preparing its bomber units to support the Sho series of defensive plans. In anticipation of an American advance on either the Philippines or Formosa, twin-engine bomber crews were trained to conduct low-level, all-weather, massed torpedo attacks at night or during low visibility conditions. Night operations were emphasized to conceal the vulnerable Betty bombers as they roared toward enemy warships on their high-speed torpedo runs.

The Imperial Navy had trained its Rikko crews to conduct torpedo attacks at night before Pearl Harbor and had refined this tactic during the war. After Saipan fell, the Imperial Navy decided to create a specialized twin-engine bomber unit trained to conduct massed attacks with over a hundred aircraft at night. Commanded by Captain Shuzo Kuno, a veteran naval aviator, this elite organization was designated the Taifu-Butai, or Typhoon Force.

Due to a serious shortage of aircraft and trained crews, the Navy grudgingly asked the Army to commit twin-engine bomber units to the Taifu-Butai under Navy command. Seeing an opportunity to expand its mission, which was to include a serious antishipping role, the Imperial Army willingly placed two of its newly re-equipped twin-engine heavy bomber regiments under naval control for use as torpedo bombers. This decision limited the number of trained Army bomber units available to flesh out the Special Duty Attack Units and execute the counterstrikes against the B-29s.

Intelligence Predictions for B-29 Operations

As the Imperial Army and Navy prepared to execute Sho 2 in September 1944, a reconnaissance plane from Iwo Jima photographed the extensive construction effort under way on Saipan and Tinian. A courier plane rushed the photos to Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo. Based on the photos and the information gleaned from B-29 operations in China and India, Japanese intelligence officers made a remarkably accurate prediction. They predicted that the airfields on Saipan and Tinian would commence large-scale B-29 operations as early as the end of October or the beginning of November 1944.

On October 10, 1944, as Imperial General Headquarters pondered its next step, the U.S. Third Fleet conducted a massive carrier air strike against the island of Okinawa. Other air strikes of equal magnitude pounded installations on Formosa and Luzon on subsequent days. Seeing a fleeting window of opportunity to inflict heavy losses on the U.S. Navy and overestimating the level of training achieved by the twin-engine torpedo bomber crews, the 2nd Air Fleet committed Japan’s last operational aviation reserve, the elite Taifu-Butai, to action.

The Imperial Navy and Army twin-engine bomber crews gamely deployed from Kyushu to stage at airfields on Okinawa with thoughts of the fate of the Empire and love for their families swirling in their minds. Beginning with a night attack on October 13, the torpedo bomber crews flew a series of low-level and near suicidal missions against Admiral William “Bull” Halsey’s powerful Third Fleet through October 15.

Celebration Dampened After Invasion of Leyte

In the face of deadly night fighter opposition and murderous proximity-fused antiaircraft fire, the aircrews pressed home their high-speed torpedo runs, crippling the cruisers Houston and Canberra, which had to be towed to safety. While the carrier Franklin was dodging torpedoes, the ship’s antiaircraft gunners shot down two twin-engine bombers at close range, one of which crashed onto and slid across the flight deck and fell into the water on the far side without inflicting serious damage to the carrier.

The returning torpedo bomber crews reported sinking 12 large ships, cruisers and above in size, and destroying 23 smaller warships. Imperial General Headquarters reported this success to the Emperor and announced a major victory to the jubilant public. On October 20, the invasion of Leyte in the Philippines snapped the Japanese out of their victory celebration, casting a long shadow of doubt on the claims of the torpedo bomber crews.

Inexperienced crews had exaggerated the results of their attacks, probably mistaking the muzzle flashes of the 5-inch antiaircraft guns on the defending warships for torpedo hits. Considering it had lost approximately a hundred twin-engine bombers, the Taifu-Butai had little to show for the costly effort. After this debacle, the Imperial Navy’s leadership initiated kamikaze missions within two weeks’ time. If the aircrews were going to die anyway, the admirals rationalized, they might as well be expended in a manner that offered a greater prospect of hitting their targets. The handful of surviving twin-engine bombers and crews returned to Japan to refit and await further orders that would not be long in coming.

Intensive Air Crew Training Commences

After the decimation of the Taifu-Butai and the American amphibious landing at Leyte, Imperial General Headquarters issued the execute order to implement Sho 1, the defense of the Philippines. For the Air Training Army Headquarters based at Kanoya, these were trying times. Even in an Imperial Army known for fielding a proliferation of diverse combat formations, the organization of the Air Training Army Headquarters was viewed as “peculiar.” Officers assigned to this staff held concurrent positions in the Air Inspectorate General Staff and Army Aeronautical Department in Tokyo, which hindered the effective performance of their increased responsibilities and duties spread over a wide geographic area. In late July 1944, this headquarters was activated and it received immediate operational control for planning purposes of several units assigned to the Air Training Army.

One of the first official acts of the Air Training Army Headquarters was to issue training directives to prepare selected units to conduct the Marianas strike operations. The most important unit alerted to prepare aircraft and crews for the counterstrikes against the B-29s was the Hokota Hamamatsu Air Training Division, an organization focused on training individual twin-engine bomber crews and entire units up to regimental size. Upon receipt of its training directive, Hokota Hamamatsu commenced training selected crews and units for the arduous, long-range missions over the open ocean. This was a unique challenge for the Imperial Army’s aviation units, accustomed as they were to leaving such missions to the Navy while they concentrated on operations over land.

Even The Army Respected The New Navy Bomber…

Through most of the Pacific War, the Imperial Army had operated various models of twin-engine bombers inferior in performance and survivability to even the Navy’s vulnerable G4M2 Betty. This changed when the new Type 4 Heavy Bomber Ki-67 Hiryu (flying dragon) twin-engine aircraft entered series production in the summer of 1944. The Hiryu bombers, which promptly received the Allied codename Peggy, re-equipped the decimated Army bomber units withdrawn from the aerial inferno in the skies over New Guinea to refit at the Hokota Hamamatsu Air Training Division in Japan. In contrast to earlier models of Japanese bombers, the Hiryu was a fast and maneuverable, heavily armed and armored twin-engine aircraft.

The Hiryu arrived too late and in insufficient numbers to play a decisive role in the outcome of the war, but it would play a dominant role in the Special Duty Attack Units created to bomb B-29 bases in the Marianas. Even the Imperial Navy, normally disdainful of all things related to the Army, from its leadership to its equipment, was impressed with the Ki-67’s superior performance. They even received deliveries of the Army-developed aircraft to outfit a portion of the 762nd Air Corps, a crack naval bomber unit that formed the nucleus of the elite Taifu-Butai.

Americans Begin A Training Operation Of Their Own

Of the Army’s aviation units placed under the Navy’s operational control in the Taifu-Butai, the 7th and 98th Air Regiments, equipped with 30 Hiryu bombers apiece, had incurred grievous losses. The 98th Air Regiment, for example, lost 11 of the 20 Ki-67s dispatched on October 12, and 15 of 16 two nights later, demonstrating that even the Hiryu was unable to survive in the face of hundreds of defending antiaircraft guns firing proximity-fused ammunition at pointblank range. These serious losses would limit the availability of Hiryu aircraft assigned to the Special Duty Attack Units when the grueling Marianas operations commenced a fortnight later. The precious Hiryu aircraft and crews expended over the ocean off Formosa would have been better utilized attacking the B-29 airfields.

On October 12, as the Taifu-Butai was springing into action off Formosa, the first B-29 from the 73rd Bombardment Wing landed at Isley Field on Saipan. More followed every day. Wasting no time, the B-29 crews commenced a serious training regimen. Training missions included flying daylight formation raids against Japanese garrisons at Dublon Island in the Truk atoll of the Caroline Islands and Iwo Jima. On November 1, a stripped-down B-29 bomber dubbed “Tokyo Rose” by its crew flew an ominous 35-minute photographic reconnaissance mission over Tokyo at 32,000 feet in broad daylight. Feeble, if frantic, Japanese attempts to down the aircraft demonstrated the ineffectiveness of the Empire’s aerial defenses when confronted with a single B-29 at high altitude.

Retaliation For The Brazen Tokyo Flyover Ordered

Stung by the aerial reconnaissance mission over Tokyo and determined to retaliate, the Imperial Navy ordered the K703 to raid Saipan. This Betty unit, like so many others, had incurred serious losses conducting night torpedo attacks off Formosa and was refitting in Japan when the orders arrived. As an afterthought, the Navy invited the Army to participate in the raid. Unwilling to lose face to the Navy, the Air Training Army Headquarters agreed to participate in the mission even though its own preparations remained incomplete.

Therefore, the first Special Duty Attack Unit consisted of a small but unknown number of Bettys, nine Hiryu bombers from the 2nd Independent Air Unit specially organized and trained for this task, and four Type 100 Ki-46 twin-engine Army reconnaissance aircraft, codenamed Dinah by the Allies. On November 2, the aircraft staged through Iwo Jima to refuel and arm. Late that night, leaving the Dinahs behind on Iwo Jima, the bombers lifted off from Chidori airfield to begin the 21/2-hour flight to Saipan and Tinian.

Japanese Raid Began With A Bad Start

Bad weather en route and over the Marianas hampered the operation from the start. Early in the morning on November 3, 1944, the bombers descended in the darkness to wave-top level to evade American radar coverage on their final approach to their targets. According to an American source, nine bombers, type unknown, dropped fragmentation bombs at 1:30 am on the runway at Isley Field, Saipan, inflicting little damage but evading the defenses on the egress. An unknown number of bombers attacked Tinian with equally poor results. Anti-aircraft guns defending Tinian shot down one bomber. A P-61 Black Widow night fighter downed a Betty over Tinian, which crashed into the Engineers bivouac area, killing four Americans and seriously wounding six.

Of the nine Hiryu bombers dispatched on this mission, five were lost to enemy action or from operational causes—a poor start for the Special Duty Attack Unit operations. As the Army reconnaissance planes did not participate in the mission, the Air Training Army Headquarters had no poststrike photos to study and remained in the dark concerning the results of this costly raid. Shortly afterward, the Imperial Navy deployed K703 to the Philippines, leaving the brunt of the combat missions over the Marianas in Army hands.

Photoshoot Prior To Attack

On November 6, a Dinah flew high overhead to photograph Isley Field on Saipan and the airfield complex on Tinian. According to postwar interrogation of a staff member of the Air Training Army Headquarters, the photographs played an important role in preparing the Hiryu crews for future missions. The same day, five more Hiryu bombers from the 2nd Independent Air Unit and two from the 4th Independent Air Unit staged through Iwo Jima. One of the Hiryu bombers belonging to the 2nd Independent Air Unit was a reserve aircraft brought along in case another Peggy broke down on Iwo Jima. It remained on Iwo Jima as the four bombers from the 2nd Independent Air Unit and two from the 4th Independent Air Unit departed Chidori on a raid to the Marianas between 10:50 and 11:26 pm.

Near the end of the flight to the Marianas, the sleek bombers descended to wave-top level and streaked over their targets in the early morning darkness. According to an American source, at 1:30 am on November 7 a single low-flying raider strafed the runway at Isley Field. Three hours later, a second aircraft buzzed the field without firing or dropping bombs. American intelligence officers surmised that this aircraft was taking photographs, but it was probably a Hiryu.

American Bombing Raid On Factory

According to a Japanese source, three bombers from the 2nd Independent Air Unit carried out a successful low-level attack at 3:30 am on Isley Field, and one bombed another airfield on the north end of Saipan. Why the American and Japanese accounts differ on the timing of the attacks is unclear, but it is probably due to the postwar Japanese account being prepared without the benefit of official records. In any event, after the first four Hiryu departed the target area, one plane from the 4th Independent Air Unit struck Isley Field while a second one bombed Tinian. Fierce antiaircraft fire from ground-based and shipboard weapons greeted the Hiryu bombers over the target area. All six bombers incurred battle damage, with one crew counting 130 holes in its plane.

The battered Ki-67s returned safely to Iwo Jima, demonstrating the survivability of this remarkable aircraft. The Japanese crews claimed 11 B-29s destroyed on the ground, but an American source indicates the battle damage inflicted on the four-engine bomber fleet was slight.

On November 24, the B-29s initiated a dreadful rain of ruin on Japan when 111 aircraft took off from Saipan and Tinian to bomb the Musashino Engine Factory, part of the Nakajima Aircraft Company, on the outskirts of Tokyo. Due to a combination of reasons ranging from encounters with the jet stream, operational losses, mechanical failures, and inadequate training, only 24 B-29s bombed the primary target, a major disappointment to the crews of the 73rd Bombardment Wing.

Strikes and Counter-Strikes: Japanese & Americans Go Blow-to-Blow

Operating at altitudes ranging from 27,000 to 31,000 feet, the B-29s recorded 184 fighter attacks. A damaged fighter rammed and destroyed a B-29 over the target, the only combat loss the bomber formation incurred during the mission. Return fire from the bombers shot down five other fighters. Japanese antiaircraft fire was ineffective over Tokyo. Imperial General Headquarters, having lost face in front of the Emperor when bombs fell on the capital, ordered an immediate resumption of the Special Duty Attack Unit operations.

The Air Training Army Headquarters alerted the 2nd Independent Air Unit to begin preparations to conduct the attack. In the afternoon of November 26, five Hiryu bombers, including one reserve aircraft, landed on Iwo Jima. Sometime that day, 11 Mitsubishi A6M5 Zero fighters also landed on Iwo Jima. The Imperial Navy, having commenced suicide attacks in the Philippines the month before, had something special in mind for the B-29 crews on Saipan.

On November 27, shortly after midnight, Tokyo time, four Hiryu bombers departed Chidori and commenced the long over-water flight toward Saipan. As the bombers neared the coast, they descended below effective radar coverage and pounded in low over the waves toward the target. All four aircraft screamed in over Isley Field at an altitude of 150 meters, strafing and bombing the B-29 dispersal areas. The attackers nailed a line of B-29s gassed and bombed up in preparation for the second raid on Tokyo that was scheduled to take off later in the morning. Luckily for the B-29 aircrews, they were not scheduled to board their aircraft until a few hours after the bombs hammered the flight line.

Surprise Attack From Zeroes

A B-29 in the 878th Squadron of the 499th Bombardment Group blew up, leaving a large hole in the ground. The low-level raiders badly damaged five other B-29s from the 878th Squadron, preventing them from paying their respects to Tokyo later in the day. Wild antiaircraft fire greeted the Hiryu crews over Saipan, but all four Ki-67s returned to Iwo Jima before first light with smiling crews and no reported battle damage.

A few hours after the last of the B-29s assigned to the second Tokyo mission had lumbered down the runway, the ground crews were surveying the damage to the flight line when a daylight raid struck Saipan. At 12:30 pm, Zero fighters from Naval Air Group 252 roared over Isley Field, dropping 250-kilogram bombs and hammering the flight line with 20mm cannon and machine-gun fire. An American account claims that 17 Zeros attacked. The official history of Japanese fighter units counterclaims that only 11 aircraft from Air Group 252, led by Lt. j.g. Kenji Omura of Fighter Hikotai 317, flew a “one-way attack” mission, an innovation that was increasing in frequency with the first kamikaze sorties flown only a few weeks before. In any event, the intrepid Zero pilots avoided radar detection with skillful low-level flying and arrived over Saipan in broad daylight before the defending P-47 and P-38 fighters scrambled.

The highly maneuverable Japanese fighters shot up the handful of B-29s left on the flight line, inflicting severe damage on a number of aircraft and killing and wounding numerous men on the ground. At least three B-29s were destroyed. One American source credits Air Group 252 with destroying or rendering unfit for combat nine B-29s on the ground, but this total may include the bombers destroyed in the day’s earlier Hiryu bombing raid.

The Mystery Of The Unaccounted Zeroes

Within seconds the antiaircraft gun crews were in action, and their effective return fire shot down most of the Zeros in short order, one of which crashed on a personnel shelter for the 500th Bombardment Group, badly injuring several men. An American source claims that antiaircraft fire downed 13 Zeros over Saipan, but it is probable that some of the “one-way attack” pilots deliberately crashed their aircraft into targets on the ground. A P-47 is credited with destroying a 14th Zero over Pagan, an island due north of Saipan that remained under Japanese control. Another P-47 pilot claimed a 15th Zero that was on final landing approach at a camouflaged airstrip on Pagan, presumably to refuel.

Zero fighters participating as part of the “one-way attack” mission carried 250-kilogram bombs under the fuselage instead of drop tanks and lacked the range to fly round trip from Iwo Jima. While the Zeros from Air Group 252 flew a “one-way attack” to Saipan, Imperial Navy practice at this stage of the kamikaze effort was to assign escort fighters to protect the raiders and report the results of the mission. Presumably, six Zero fighters from an unidentified unit escorted this mission, which would square with American accounts of 17 Zeros participating in the raid. The escorts would have carried drop tanks on their bellies in place of bombs.

If six fighters escorted the mission, then antiaircraft fire downed two over Saipan and P-47s shot down two more aircraft in the vicinity of Pagan. The fate of the remaining Zeros is unknown. Perhaps the pilots succeeded in returning to Iwo Jima to report the results of the raid without having to refuel on Pagan. The elusive truth remains one of the minor mysteries of the Pacific War.

Japanese Miss Golden Opportunity Due To Poor Timing

Air Group 252’s mission marked the demise of Japanese daylight air raids on the Marianas. The cost was prohibitive. It is worth contemplating what might have occurred if Air Group 252 had struck earlier, when the B-29s were taxiing with full bomb loads to begin the second mission to Tokyo, or had waited to strike until the fuel-starved bombers were in the pattern to land after completing the last leg of the long-range mission. An excellent opportunity was lost through poor timing.

At 1:00 am on November 29, twin-engine bombers struck Isley Field again, inflicting little damage. Antiaircraft guns nailed one of the low-flying bombers as it flashed over the runway and plowed into the ground. The identity of the attackers is in doubt. A staff officer from the Air Training Army Headquarters did not mention this raid in a monograph he prepared for the Americans after the war. A Betty-equipped Imperial Navy squadron may have flown the mission, even though the better known Betty units, such as K703, were in the Philippines at this time.

Attack On Isley Field Costly To The Japanese

Air Training Army Headquarters claimed responsibility for the next major strike on the Marianas. On the afternoon of December 6, 1944, elements of the 110th Heavy Bomber Regiment advanced to Iwo Jima with 10 Hiryu bombers, the largest concentration of Army bombers yet committed to a Special Duty Attack Unit. After refueling and arming their aircraft, the crews ate a hurried dinner under the wings of their planes. Before taking off, the aircrews received final tactical instructions to make repeat strafing runs over Saipan after dropping their bombs on the first pass. Late that night, all 10 aircraft rolled down the runway in the darkness, destination Saipan. Two of the bombers encountered mechanical difficulties and returned to Iwo Jima. The remaining eight Hiryu dropped down to wave-top level to evade the probing American radar.

Flying under radio silence, the eight bombers split into two distinct four-ship elements before they crossed the coast. One element of four aircraft attacked Isley Field from an altitude of 150 to 300 meters; the second rushed in from another direction at 300 to 400 meters. Surprise appeared complete. As the bombers crossed the coast, the amazed crews saw the airfield dead ahead and lit as bright as day. On their first deadly pass, the Hiryu attacked a group of B-29s parked on the taxiways in preparation for a raid on Japan, destroying three planes with high-explosive bombs. Three other B-29s were badly damaged. Twenty additional aircraft received moderate to light damage.

Intense antiaircraft fire welcomed the low-level raiders with a wall of flying shrapnel. The mission commander witnessed two Hiryu bombers blow up on his first pass over the airfield. Japanese sources concur with American claims that six bombers were shot down. Antiaircraft gunners on Saipan claimed one bomber, while gun crews on Tinian, which was not on the target list that night, claimed another. A minesweeper offshore shot down a third Peggy. Two damaged Hiryu bombers limped back to Iwo Jima to report the success of the raid.

“Intruders Were Not a Very Good Substitute For Santa Claus”

In retrospect, the Japanese bomber crews threw away the element of surprise when they conducted the repeat strafing runs over Isley Field. From a tactical perspective, it was a costly mistake for the Hiryu crews to duel with the sharpshooting antiaircraft gunners.

For the next two weeks, the Japanese limited their aerial activities over the Marianas to occasional reconnaissance flights flown by the twin-engine Army Ki-46 Dinah and the single-engine Navy C6N1 Saiun, codenamed Myrt. On December 20, a P-61 Black Widow attempted to intercept a reconnaissance plane that had slipped behind a B-29 returning from a mission over Japan, but the Japanese aircraft evaded and returned to Iwo Jima.

At 10:10 pm on Christmas Day 1944, an estimated 24 low-level raiders struck Isley, East, and Kobler Fields on Saipan in an intense air raid lasting about an hour. As the Air Training Army Headquarters was deactivated the next morning and replaced by the 6th Air Army Headquarters and no one from this organization prepared a monograph on the Special Duty Attack Units after the war, it is unknown which unit or combination of units flew the mission. The leading contender is the Army’s 7th Heavy Bomber Regiment, still under the Navy’s operational control, which is reputed to have joined its sister units in bombing raids over Saipan during the closing weeks of 1944.

P-61 Black Widows claimed three confirmed aerial victories opposing the raid, while the antiaircraft gunners claimed a probable. The raiders left a swath of destruction on the three airfields. Burning B-29s marked their passing. As one American source explained, “The intruders were not a very good substitute for Santa Claus.”

Okha “Glide Bombs” Probably Didn’t See Action At Saipan

An American account of the Christmas Day raid claims that a “glide bomb” destroyed one B-29, though this seems unlikely. With the exception of the Navy’s manned Ohka rocket-bomb, designed for employment in an anti-shipping role, the Japanese fielded no other known standoff weapons during the war. A specially modified G4M2E Rikko carried the Ohka slung under its belly until the target was sighted. Then the Ohka pilot entered the rocket-bomb’s cockpit through the Betty’s open bomb bay doors. After the bomber released the rocket-bomb, the Ohka pilot ignited the rocket engines and flew his small plane with its high-explosive warhead into a target.

The Imperial Navy used an aircraft carrier to transport Okha rocket bombs to the Philippines on two separate occasions during 1944, but U.S. submarines foiled both attempts. Therefore, Ohka bombs were available for employment on the Christmas Day bombing mission over Saipan, and two Ohka sorties were flown with the intent to crater American runways during the Okinawa campaign. But the combat debut of the Ohka is believed to have occurred on March 21, 1945, so it seems unlikely that one was fired at an airfield on Saipan.

At 3:35 am on January 2, 1945, one twin-engine bomber streaked low over Isley Field and dropped its bombs, disturbing the post-New Year’s reverie. This bomber destroyed one B-29 and damaged three others. Night fighters intercepted another lone raider half an hour later north of Saipan. The unidentified aircraft evaded interception and returned to Iwo Jima.

Curtain Comes Down On Special Duty Attack Operations

Later in the day, high-flying P-47s were waiting in ambush when a Myrt reconnaissance plane flew over Saipan at 12:25 pm. An accurate burst from a Thunderbolt’s eight .50-cal. machine guns dispatched the hapless reconnaissance plane over Marpi Point. At 4:13 am the next morning, January 3, a defending P-61 intercepted and shot down a Rikko 35 miles north of Saipan.

The brief era of Special Duty Attack Unit operations ended when this twin-engine bomber crashed into the sea. Formations of Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers and B-29s had been carpet-bombing Iwo Jima repeatedly to pound suspected Japanese defenses and the airfields. Bomb craters pockmarked the runway at Chidori and overwhelmed the 27th Air Flotilla’s strenuous efforts to keep it operational. Moreover, the U.S. Navy’s submarines, coupled with long-range antishipping strikes flown from the Marianas, slaughtered the coastal freighters and fishing trawlers pressed into transporting bombs and fuel to the volcanic island.

Two days later, at noon on January 5, another reconnaissance plane was chased by American fighters, but it evaded interception and returned in haste to Iwo Jima. Ten days later, a Myrt was intercepted at 31,000 feet by a P-47 and shot down short of Tinian. On February 2, two Grumman F6F Hellcats jumped a Myrt at 13,000 feet 20 miles north of Saipan and shot it down in flames.

Air Attacks Were The Impetus For The Iwo Jima Invasion

With this final American aerial victory, Japanese operations over the Marianas came to an inglorious and fiery end. A conservative American estimate credits the Special Duty Attack Units with 17 B-29s destroyed on the ground or rendered unfit for combat due to extensive battle damage. The bravery and competence of the Japanese pilots and crews, and the success they achieved during low-level bombing raids in the face of murderous defensive fire and determined fighter attack, was a dual-edged sword. There were many reasons behind the American decision to initiate the costly Iwo Jima invasion and the elimination of a staging base for the Special Duty Attack Units was one of them.

On February 19, 1945, the V Amphibious Corps commenced an unwavering amphibious assault on Iwo Jima in the face of fierce and effective Japanese opposition. Air Field Number One was soon overrun in bitter fighting. Two weeks into the brutal month-long battle for the volcanic island, a strange sight materialized in the sky over the fire-swept ground. A fuel-starved B-29 named “Dinah Might” touched down under sporadic mortar fire on Chidori after raiding Japan.

The former staging point for the Special Duty Attack Units provided succor for this B-29 and the over 2,000 battle-damaged bombers that followed until the war was won. The Pacific War had once again turned full circle. The Stars and Strips fluttering over Mount Suribachi and the B-29 taxiing below portended the bloody downfall of the Empire of Japan.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments