By Todd A. Raffensperger

At 1:30 am on August 21, 1968, Czech authorities at Ruzyne Airport in the capital city of Prague waited to greet a special flight that was flying in directly from Moscow. The authorities were not alarmed. Perhaps it was a delegation coming to try to hammer out the growing differences between Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union.

As soon as the plane taxied to the terminal, it became apparent immediately that it was no official delegation—diplomatic or otherwise. Instead, 100 plainclothes Russian soldiers armed with submachine guns clambered down the catwalk to the tarmac and stormed the airport terminal and control tower, overcoming the Czech security personnel without firing a shot. They were an advance unit of the Soviet 7th Guards Airborne Division. With the airport secured, the commandos signaled all clear for the rest of the Soviet airborne invasion force to proceed. It was the beginning of the end for Czechoslovakian democracy, which was being virtually strangled in its crib.

Around the world, 1968 had already been a year of turmoil. In the United States, the year was marked by the shocking assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy. A growing number of Americans were taking to the streets, protesting the ever-escalating war in Vietnam, clashing with police and National Guard units, and taking over administration buildings at colleges and universities. The antiwar, antiestablishment furor was catching on in Europe as well, with similar demonstrations in West Germany by activists protesting the continuing American military presence in their country. Throughout France, mass demonstrations and strikes by students and workers were paralyzing the French economy and pushing the de Gaulle government to the point of collapse.

Communist leaders within the walls of the Kremlin were comforted by the thought that their own closed-off societies, isolated from the West by barbed wire, guns, and tanks, were immune to the sort of disorder and strife that was gripping the capitalist world. They hadn’t counted on Czechoslovakia.

Czechoslovakia: The Warsaw Pact’s Stable Eastern Flank?

Unlike in most of the other Eastern European countries that came under Soviet occupation after World War II, in Czechoslovakia the communists came to power in 1946 through electoral victories. But when in 1948 it became apparent that they were losing their popularity and thus were going to lose the next round of elections, the communist prime minister, Klement Gottwald, cracked down on all noncommunist factions in the government and used the militia and police to seize control of Prague. From then on, the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic solidified its communist ties and joined the ranks of the other Eastern and Central European vassal states in the Soviet Empire.

The Czechoslovak Peoples Army (CSLA), numbering 250,000 men, was structured along the lines of the Soviet Army. Its officer corps was composed almost entirely of men trained by the Soviets who had served in the First Czechoslovak Army Corps on the Eastern Front during World War II. Those officers from the prewar Czechoslovakian Army who had gone to London during the war and had come back after 1945 to help reconstitute the country’s military were purged from the ranks. During the 1950s, when East Germany, Poland, and especially Hungary were wracked by uprisings, Czechoslovakia remained a stable, solid part of the Eastern Bloc. The Soviets were so confident of the stability and loyalty of the Czechs and Slovaks that they did not even keep a standing Red Army contingent in the country. In the event of a war with NATO across Germany, the Czechs were expected to hold up the Warsaw Pact’s southern flank.

Humiliation in the Six-Day War

But by the 1960s, conditions within Czechoslovakia had started to change. Gottwald was dead, and in his place was a cautious reformer named Antonin Novotny. Unlike his predecessor, Novotny was willing to allow a certain limited degree of reform and loosening up of Czechoslovak society. He even went so far as to give businesses a little leeway in dictating their own production schedules and business plans.

In 1967, events in the Middle East altered Czechoslovakia’s political course. In June of that year, Israel overwhelmingly defeated the combined forces of Egypt, Syria, and Jordan in the Six Day War. The Syrian and Egyptian armies had been largely trained and equipped with advisers and weapons from the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, including Czechoslovakia. To many Czechs and Slovaks, Egypt’s and Syria’s humiliation was also their own.

The Six Day War provoked many among Czechoslovakia’s intellectual elite to begin questioning the government’s support for Egypt and its antipathy toward Israel. This criticism in turn opened up the floodgates to criticism of the government in general and of Premier Novotny in particular. Some of the first open critics of the regime were the members of the Writers Union, which numbered among its ranks a young playwright, Vaclav Havel, who was just beginning to make a name for himself. Novotny reacted to the criticism by reimposing censorship and clamping down on the press, moves that only engendered more criticism, both inside and outside the party. By the end of the year, there were calls within the Central Committee for Novotny’s resignation.

The Fall of Novotny, the Rise of “Our Sasha”

When the committee met again in January 1968, the decision was made to strip Novotny of most of his power by separating the offices of first secretary of the party from the office of president of Czechoslovakia. Novotny previously had held both posts, and he was allowed to keep the office of president; but the first secretariat went to the head of the Slovakian wing of the party, Alexander Dubcek.

Dubcek was the son of Slovakian immigrants who had come to the United States and become American citizens. Active in the American socialist movement, they had both worked for Eugene Debs’s Socialist Party at the turn of the century. In 1921, Dubcek’s father, Stefen, moved the family to the Soviet Union to help build an industrial cooperative. The family moved back to their homeland of Czechoslovakia in 1938. As a teenager, Dubcek and his brother joined the Slovakian resistance against the Nazi occupation and took part in the Slovak national uprising in August 1944. Dubcek was wounded and his brother was killed in the fighting.

After the war, Dubcek climbed the ladder of the communist hierarchy and became a champion for the Slovak minority within the country. He made a name for himself as an advocate of government reform, including the separation of the party organization from the government. Dubcek was not known for being a maverick, but for being a hard worker, a fervent believer in Marxism-Leninism, and an admirer of the Soviet Union. Among his comrades in the Kremlin, Dubcek was affectionately referred to as “Our Sasha.”

Dubcek’s appointment was a welcome development for reformers in Czechoslovakia, but it did nothing to mollify the tens of thousands of people who had started taking to the streets and publicly demanding Novotny’s resignation as president. On March 22, 1968, they got their wish; Novotny finally conceded the inevitable and stepped down. His successor was a former general and war hero named Ludvik Svoboda, who supported Dubcek’s proposals.

“Czechoslovakia’s comrades know best”

What followed was an unprecedented period of freedom and reform behind the Iron Curtain that would be remembered in history as the “Prague Spring.” For the first time in more than 20 years, the people of Czechoslovakia were not only allowed but encouraged to speak up and criticize the government and the party. Economically, Dubcek instituted an action program that loosened government controls on the private sector to an extent that Novotny had never dared. It wasn’t long before the man whom the Soviets had regarded as a loyal, orthodox communist was declaring the desire to establish a “free, modern, and profoundly humane society.”

Dubcek’s neighbors and fellow Warsaw Pact leaders wanted no part of such an open society. They made their feelings known to Dubcek during the March 23 Warsaw Pact summit meeting in Dresden. Heading up the campaign of denunciation was Dubcek’s neighbor to the north, East German leader Walter Ulbricht. The architect of the Berlin Wall and the most Stalinist of the Warsaw Pact leaders, Ulbricht was more than a little concerned about the possibility that the newfound freedoms of the Czech and Slovak citizens would tempt his own citizens to demand the same. He denounced Dubcek for laying open Czechoslovakia to infiltration by Western influences and for giving his nation’s artists and writers too much freedom. “The capitalist world press had already written that Czechoslovakia was the most advantageous point from which to penetrate the socialist camp,” he exclaimed.

Poland’s communist leader, Wladislaw Gomulka, shared Ulbricht’s hysteria and went so far as to remind Dubcek of how Hungary was invaded and crushed in 1956 after its leadership had strayed too far from the Soviet fold. Ironically, Hungarian leader Janos Kadar, who had replaced the unfortunate Imre Nagy after Nagy was executed by the Soviets in 1958, took a more moderate tack, concluding that “Czechoslovakia’s comrades know best, I believe, what is happening in Czechoslovakia today.”

Brezhnev and Dubcek at the Dresden Meeting

Whatever the leaders of the Eastern Bloc felt about what was happening in Czechoslovakia, it ultimately was not up to them as to what to do about it. No matter how much they exalted themselves within their own countries, the fact remained that they served at the pleasure of their Soviet masters. The question of what to do about Czechoslovakia rested within the halls of the Kremlin and on the shoulders of one man, General Secretary of the Soviet Union Leonid Brezhnev. Brezhnev had come to power in 1964 after Nikita Khrushchev was ousted over his supposed mishandling of the Cuban missile crisis. Unlike the temperamental, risk-taking Khrushchev, who always favored bold moves and ideas, Brezhnev was a cautious man who prized stability above all else.

Brezhnev at first was reluctant to get involved with events in Czechoslovakia. He had no problem with Novotny’s ouster, and he had nothing against Dubcek himself. When asked by the desperate Novotny and other Czech hard-liners to intervene, Brezhnev replied: “I shall not deal with the problems that have arisen in your country. I know your party and the road it has traveled along, that is why I am confident that this time, too, it will adopt the kinds of decisions that are in the Leninist spirit.” He was unwilling to sign off on a military operation against a fellow Warsaw Pact member unless it was absolutely necessary. Furthermore, Brezhnev had a personal connection with Czechoslovakia, having been a commissar in the Soviet armies that liberated the country from the Nazis in 1945. He was also friends with Czech President Ludvik Svoboda, whom he knew from the war.

It was the Soviet leader’s hope that the situation could be resolved through negotiation. At the Dresden meeting, Brezhnev reiterated his opinion that every communist party had the right to make changes and reforms where it saw fit. But he also expressed concern that the changes that Dubcek and the reformers were making inside Czechoslovakia were going too far, especially in the area of allowing criticism of the party and of the socialist system. It especially irked him that even the party newspapers were using phrases like “decayed society” and “outdated order” to describe communism. Brezhnev reassured Dubcek that he would enjoy the full support of the Soviet leadership and the Warsaw Pact in taking whatever steps necessary to “stop these very dangerous developments.” Through all the criticism, Brezhnev tried to maintain the air of fraternity among the parties.

Dubcek tried to maintain this sense of fraternity as well, constantly reassuring the Soviets and Warsaw Pact partners that there was no intention by his government to take Czechoslovakia out of the pact. Nor did he have any intention of abandoning socialism, a set of ideals he had believed in his entire life. He asserted that his reforms would serve to strengthen socialism, by ensuring the rights of the working class and encouraging workers’ participation in socialism’s further development. The action program of April 1968, drawn up by Dubcek and approved by the Central Committee, included a section entitled “Socialism Cannot Do Without Enterprises.” Included were proposals to give private enterprises more freedom to act in foreign markets; to include consumer, labor, and other interests in the decision-making process; and to draft an economic plan that would be subject to the authority of a democratically elected National Assembly. But where Dubcek saw a brighter future for socialism in Czechoslovakia, Brezhnev and others saw only danger.

Andropov’s Deception

Another voice joined the chorus that was whispering alarm and threat into Brezhnev’s ear. It was that of Yuri Andropov, chairman of the Soviet Union’s notorious intelligence arm, the KGB. Andropov had made a name for himself in 1956 as ambassador to Hungary, where he was able to allay the worries of Hungarian Prime Minister Imre Nagy about Soviet intentions right up until the moment that the Soviets invaded. His role in crushing the Hungarian uprising guaranteed his ascendancy to the Central Committee. Andropov made it his priority to crush any hint of dissident activity within the Soviet Union, creating an entire department within the KGB for the sole purpose of investigating, harassing, and persecuting dissidents including Andre Sakharov and Alexander Solzhenitsyn. He shared the anxiety that Ulbricht and Gomulka felt about what was going on in Czechoslovakia, and he was determined to make Brezhnev feel it as well.

Andropov had help from his counterpart in Czechoslovakia, the head of the Czech secret police agency known as the Statni Bezpecnost, or StB. His name was Josef Houska, and he was among many within the Czechoslovak security apparatus who opposed the Prague Spring. Together, the two security chiefs plotted to undermine Dubcek and to convince Brezhnev of the necessity to intervene in Czechoslovakia. While Houska fed information to Moscow identifying a so-called counterrevolutionary conspiracy in Prague, Andropov sent 30 KGB undercover agents to Czechoslovakia posing as tourists, in the hope that Czechs would reveal anti-Soviet and anti- communist sentiments to them. These agents were also tasked with putting up inflammatory posters and fliers calling for Czechoslovakia’s withdrawal from the Warsaw Pact and the end of the communist system.

Andropov fed Brezhnev and the Politburo a steady diet of misinformation about counterrevolutionary activity going on in Prague, within the government itself. Reports of supposed arms caches being found throughout the country, no doubt planted by the StB or KGB, were used to claim that a massive armed uprising was in the offing. The KGB chairman also saw to it that stories appeared in Pravda revealing details of a supposed CIA plan to sabotage Czechoslovakia and penetrate the country’s intelligence and security services. The KGB’s head of counterintelligence in Washington, Oleg Kalugin, sent a report to his boss insisting that no such plan existed, that in fact the United States government had been caught off guard by the Prague Spring, but Andropov made sure the report never reached Brezhnev’s desk.

Preparing for Operation Danube

Dubcek was not unmindful of what was happening, and he knew that there were those in his own government who were plotting against him. Throughout the summer a steady escalation of rhetoric came from both sides. There was still no decision by Brezhnev about military action. Just the same, the Warsaw Pact started getting ready. A slow but steady assembly of armored and infantry units from East Germany, Hungary, Bulgaria, Poland, and the USSR started deploying closer to the Czech border. On July 21, Ulbricht ordered the mobilization in the Leipzig region of East German forces, including the 7th Armored and 11th Motorized Infantry Divisions. Meanwhile, the Warsaw Pact high command mobilized the entire Polish Second Army, consisting of four motorized infantry divisions. Three days later, the Hungarian 8th Mounted Infantry Division was also mobilized. The Bulgarians threw in with two regiments deployed to Soviet territory in the Ivanovo-Frankovsk area. These forces complemented the Soviet 1st Armored Army of the Guards, 20th Mounted Infantry Army of the Guards, 11th Armored Army of the Guards, the 38th Armored Army, and units from the Soviet Southern Military Group.

The assembled forces for what was code named Operation Danube numbered well over 250,000 troops. It was left to the supreme commander of the Warsaw Pact forces, Marshall Ivan Yakubovskii, to coordinate these forces when, and if, he got his orders to do so from Comrade Brezhnev and the Politburo. The officers and men of Operation Danube were told by their superiors that there would be little trouble. Indeed, it was their understanding that any intervention would meet with the full support of the Czech and Slovak peoples, who would see their arrival as a rescue from counterrevolutionary plotters. The Soviet defense minister, Marshal A.A. Grechko, underscored this point by stating emphatically to all his commanders that “Czechoslovakia is a friendly country. We are going to our brothers. On no account must we permit the spilling of blood of Czechs and Slovaks.”

On August 17, the Politburo at Brezhnev’s urging passed a resolution that declared that “the time has come to resort to active measures in defense of socialism in the CSSR and [we have] unanimously decided to provide help and support to the Communist Party and the People of Czechoslovakia with military force.” Two days later, the Soviet ambassador in Prague, Stepan Chervonenko, delivered a letter of warning to the Czech leadership. It was nothing less than an ultimatum demanding that Dubcek and the party reassert complete control over the media, crack down on dissidents and critics, and repeal all economic and political reforms that threatened the communist hold on power. While not explicitly threatening an invasion, the letter stated that the demands must be met without delay or the matter “would be extremely dangerous.” Dubcek got the message, and he readily accepted the demands laid out by Brezhnev. But by then the invasion was already under way.

The Warsaw Pact Invades Czechoslovakia

A couple of hours after midnight on August 21, while Soviet paratroopers were securing Ruzyne Airport, the forces of five Warsaw Pact nations began crossing the border into Czechoslovakian territory. Seventeen tank and motorized infantry divisions swarmed into Czechoslovakia with more than 2,000 tanks, mostly T-55s and T-62s, and other armored vehicles. Soviet, Bulgarian, and Hungarian forces pushed from the southeastern border, linking up with Soviet airborne forces that landed and occupied the Slovakian provincial capital of Bratislava, and then moved on along the Czech-Austrian border. These forces linked up with the two Soviet and one Polish force that came in from the northeast, reaching Brno in the center of the country, which already had been occupied by Soviet paratroopers. On the right flank, coming in from the northwest, were Soviet and East German forces from the German Democratic Republic, units that originally had trained to fight a war against NATO forces deployed in West Germany. Now their guns were turned in a different direction.

The ground operations were supported by a concentration of 500 Soviet and Warsaw Pact combat aircraft, including MiG-19 and MiG-21 fighters. Meanwhile, a stream of Antonov AN-12 transports was landing at Ruzyne Airport on an hourly basis, offloading equipment and personnel of an entire Soviet airborne division. Similar airborne operations were also under way in the cities of Brno and Bratislava.

One of the first government leaders to get an inkling of what was happening was Dubcek’s minister of defense, General Martin Dzur. When he first started receiving reports of movement along the borders, Dzur took it upon himself to issue an order that remains controversial to this day. Realizing that an invasion was imminent, he ordered his forces to remain in their barracks. No weapons were to be used under any circumstances, and the invaders were to be given “maximum all-round assistance” by the Czech military.

It didn’t take long for the invaders to reach their assigned objectives. Units fanned out across the countryside, securing airports, telegraph offices, armories, barracks, radio stations, and party headquarters offices. Faithful to their orders, Czech Army units stayed in their barracks and offered no resistance anywhere.

“The Whole World is Watching!”

As the long, rumbling columns of tanks, infantry, and artillery moved through the Czechoslovakian countryside, residents awakened by the sound of military vehicles first believed that it was merely an exercise, like others in the past carried out by their army and their Warsaw Pact allies. It was only when they turned on their radios that they started hearing the first reports of a major invasion of their country. Instead of the invaders waving the Nazi swastika, this time they were now waving the hammer and sickle of their old friend and protector Russia.

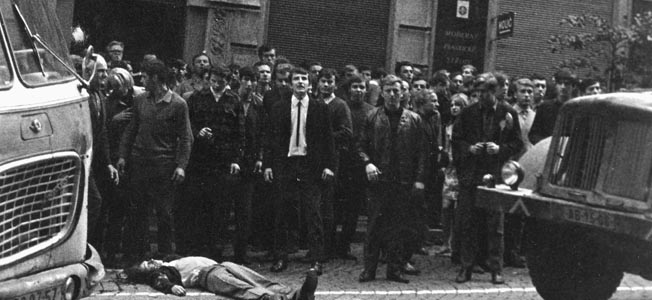

As word spread throughout the country, Czechoslovak citizens, mostly young people, started coming out in large and angry groups. “The whole world is watching! The whole world is watching!” they chanted, as television cameras recorded the confrontation. At first all they did was hurl insults and chants at the invaders, but before long they started throwing bricks, bottles, and stones. In some areas, citizens erected makeshift barricades to thwart the Soviet advance. The intensity of their anguish and hatred was something the Warsaw Pact soldiers had not been prepared for. They had been told that they were coming to save the people from a counterrevolutionary takeover that threatened their socialist paradise. As a result, the young soldiers, many of whom were from peasant or rural backgrounds, did not know how to react. It was a formula for violence.

By 4:30 am, Soviet military vehicles arrived outside of the Central Committee building in Prague. Dubcek was on the telephone in his office trying to get more details about the invasion when a group of soldiers and plainclothesmen, led by a Soviet colonel, barged into the room. Without even the pretense of courtesy, the colonel walked up to Dubcek, yanked the receiver out of his hands, and pulled the telephone cord out of the wall. Announcing himself as a representative of a “revolutionary committee,” the colonel ordered, “Comrade Dubcek, you are to come with us straight away.” With that, Dubcek was led away under arrest.

The Defiant Stand of Radio Prague

In the streets of Prague, all hell was breaking loose. Soviet tanks from East Germany were met by crowds of angry Czech citizens who at first tried to talk to the soldiers and persuade them that there was no counterrevolutionary plot. But the bewildered soldiers continued on to their objectives. Soon enough, the peaceable appeals by the people were replaced by chants, threats, and violence. Some protesters climbed onto the tanks and vehicles in an attempt to open the hatches and get at the crews, or tried to set them on fire. The soldiers bearing the brunt of the anger and violence soon started to respond in the way they had been trained, by opening fire on the protesters.

The most intense fighting occurred outside the broadcast center of Radio Prague. The radio station had become the only fountainhead of defiance against the invasion. Protesters tried to protect the building by ringing it with city transit buses and setting them on fire. Soviet tanks and vehicles that tried to ram the makeshift fortifications sometimes caught fire themselves. People continued to surround the tanks, but the station’s capture was inevitable, and by the end of the day Operation Danube had achieved all its key objectives.

The Moscow Protocols

While his people struggled to resist Soviet tanks with their bare hands, Dubcek and other reformers were being shuttled from base to base while the leaders in Moscow tried to find hard-line replacements who could take the reins of power and restore order in a new government. But those few hard-liners on whom the Soviets could count did not have the clout and credibility to win over the members of the Central Committee or the Presidium, who stood in passive but solid defiance to the Soviet actions.

Realizing that they were going to have to work with the leaders who were already in place, the Russians flew Dubcek and the others to Moscow on August 24. There Dubcek was reunited with Svoboda, who had been flown to Moscow earlier. They met with Brezhnev and other members of the Politburo, and two days later, with little choice in the matter, they signed the Moscow Protocols, a document that the Soviets had already drawn up before the meeting began. It was a revocation of almost everything that had been put in place during the Prague Spring. It repealed the economic reforms, it banned opposition groups, and it reasserted state control over the media. Dubcek, Svoboda, and other Czech reformers tried to haggle some concessions from the Soviets, but in the end Brezhnev got everything he wanted.

The Soviet leader subjected Dubeck to a final, humiliating lecture to drive home who were the true masters of in Eastern Europe. “The borders of your country are our borders as well,” said Brezhnev. “Because you did not listen to us, we feel threatened.” Brezhnev declared that in the name of those Soviets killed to liberate Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union was fully entitled to intervene militarily when it believed that the security of the socialist community was threatened. “It is immaterial,” Brezhnev asserted, “if anyone was actually threatening us or not. It is a matter of principle. And that is the way it will be, for eternity.” This prerogative that Brezhnev claimed for the Soviet Union in its East European satellites would become known as the Brezhnev Doctrine, holding that the USSR had the right to intervene in any communist country where it felt its interests were in jeopardy.

Dubcek returned to Prague on August 27 a broken man. With his eyes welling up with tears and his voice quivering at times, he addressed the Czech people on the radio for the first time since the invasion, telling his fellow citizens to refrain from any further confrontations with the invaders. He also told his saddened listeners that the situation would force them to “take some temporary measures that limit democracy and freedom of opinion.” It was the best face that Dubcek could put on the situation, but everyone knew that it represented the end of the Prague Spring.

A Moral Victory for the West

By military estimates, Operation Danube was a flawlessly executed success. It went off with a level of efficiency and coordination that made it a textbook exercise for Soviet military operations. In terms of casualties, the Soviet and Warsaw Pact forces suffered fewer than a couple dozen fatalities or injuries. Some 100 Czechoslovakian men and women, mostly young protesters, were killed and hundreds of others were wounded. As far as Soviet military operations would go, the invasion of Czechoslovakia was relatively bloodless.

In short-range and longer political terms, the crushing of the Prague Spring would have disastrous consequences for the future of world communism. The communist and socialist parties in the Western democracies lined up in condemning the Soviet actions. For them, the invasion ran contrary to everything that they had been arguing for, a crushing of individual freedom that was taken for granted in the Western world.

Prague Spring’s Legacy: The Velvet Revolution

Criticism came from within the Eastern Bloc as well. The communist dictator of Albania, Enver Hoxha, condemned the invasion and withdrew his tiny fiefdom from the Warsaw Pact. Romania was the only major Warsaw Pact member that categorically refused to send troops to join the invasion force, with its dictator, Nicolai Ceaucescu, publicly condemning the invasion as flagrant violation of one socialist country’s sovereignty by another. His high-profile opposition would endear him to Western leaders, who would treat him as a liberal maverick who was bucking Soviet orthodoxy, overlooking the fact that Ceaucescu was a tyrant to his own people. Seeing an opportunity to try to cast itself as the true leader of world revolution, the People’s Republic of China also roundly condemned the Soviet invasion.

Perhaps the most profound impact that the crushing of the Prague Spring would have would be among the Soviets themselves, especially the younger generation of activists who saw their hopes for a more reformed, humane type of socialism crushed under their own country’s tank treads. For millions of people who lived behind the Iron Curtain, the invasion of Czechoslovakia killed whatever hope they had that communism could ever change on its own.

Twenty-one years later, the long-discredited socialist system in Czechoslovakia was finally toppled by what would be called the “Velvet Revolution.” It was a bloodless uprising similar to those that already had occurred in East Germany and almost all of the rest of Eastern Europe. As Czechoslovakia’s citizens rejoiced in the downfall of the old regime, one of those for whom they cheered the loudest was Alexander Dubcek, who had long since resigned from the government, been stripped of his party membership, and been relegated to a meaningless job with the Slovakian forestry commission. But like the embattled country he had led so briefly in the Prague Spring of 1968, Dubcek survived to see a final triumph over communist oppression. In the end, perhaps, the good guys won.

Many years ago in graduate school had a seminar on the structure and practices of the Communist Party. The professor, Dr. Kamil Winter, was originally from Czechoslovakia, and was head of Czech TV when he defected to the West, probably around 1968. The three of us sat in the professor’s office and sat spellbound, just soaking in all the professor had to say, asking the occasional question. No textbook needed. Took a lot of notes. No paper required, don’t even remember any tests. A most worthwhile course, have never forgotten it or Dr. Winter, quite a gentleman.