By B. Paul Hatcher

“With the coming of the Second World War, many eyes in imprisoned Europe turned hopefully, or desperately, toward the freedom of the Americas. Lisbon became the great embarkation point. Not everybody could get to Lisbon directly, and so a tortuous, roundabout refugee trail sprang up: Paris through Marseilles, across the Mediterranean to Oran, then by train or auto or port across the rim of Africa to Casablanca in French Morocco. Here the fortunate ones, through money or influence or luck, might obtain exit visas and scurry to Lisbon and from Lisbon to the new world. The others wait in Casablanca and wait and wait and wait.”

—Introduction to the movie Casablanca

(Warner Brothers, 1942)

For the first time in over 400 years, the small nation of Portugal was one of the most important places on earth during WWII. At the airport in Lisbon, its capital city, planes from London, Rome, and Berlin boarded side by side, while spies, emissaries, and diplomats stood in line within a grenade’s throw of one another.

By mid-1940, over 20,000 refugees, some rich, some not so rich, and some royalty, crowded Lisbon’s resorts, cafés, and boarding houses. They awaited transportation to a variety of potential destinations: Britain, the United States, Argentina, Brazil. Readily available were newspapers and propaganda from Italy, Britain, and Germany alike. Portugal, through its dictator Antonio de Oliveira Salazar, had declared itself neutral at the outbreak of hostilities in 1939, and politically its attention was focused on keeping that neutrality, as well as keeping Spain neutral, all the while maintaining a treaty of friendship with Great Britain which had existed since the 14th century.

Other neutral nations had seen their neutrality challenged and protested by the principal belligerents, especially Britain and Germany. Throughout the war, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and especially Ireland and Spain, had come under immense pressure from the belligerents to declare allegiance and begin contributing immediately to the war effort. Not so Portugal. Great Britain favored Portugal’s neutrality and considered Portugal’s potential belligerence more of a liability than an asset. If Portugal were to declare war against the Axis, or to otherwise provoke an Axis movement against it, Great Britain figured it would further strain its already fully stretched resources in coming to Portugal’s rescue. By mid-1940, with the fall of France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Denmark, and Norway, with Britain’s defense of its homeland now straining the island nation beyond its means, the addition of Portugal as a British ally would assuredly result in the fall of that nation as well, with the possible addition of Spain to the Axis side.

Meanwhile, Hitler gave little thought to Portugal. Although the German military had drafted extensive plans for the potential invasion of Sweden and Switzerland, Portugal had strategically little to offer the Wehrmacht, with one major exception. The Azores Islands were a Portuguese possession located in the Atlantic Ocean. In the early 15th century, Portuguese explorers discovered the Azores Islands, which lay strategically one-third of the way between Portugal and New York City. Uninhabited, they were settled and farmed by the Portuguese, but by mid-1940 an airbase in the Azores had acquired a new and somewhat unique importance.

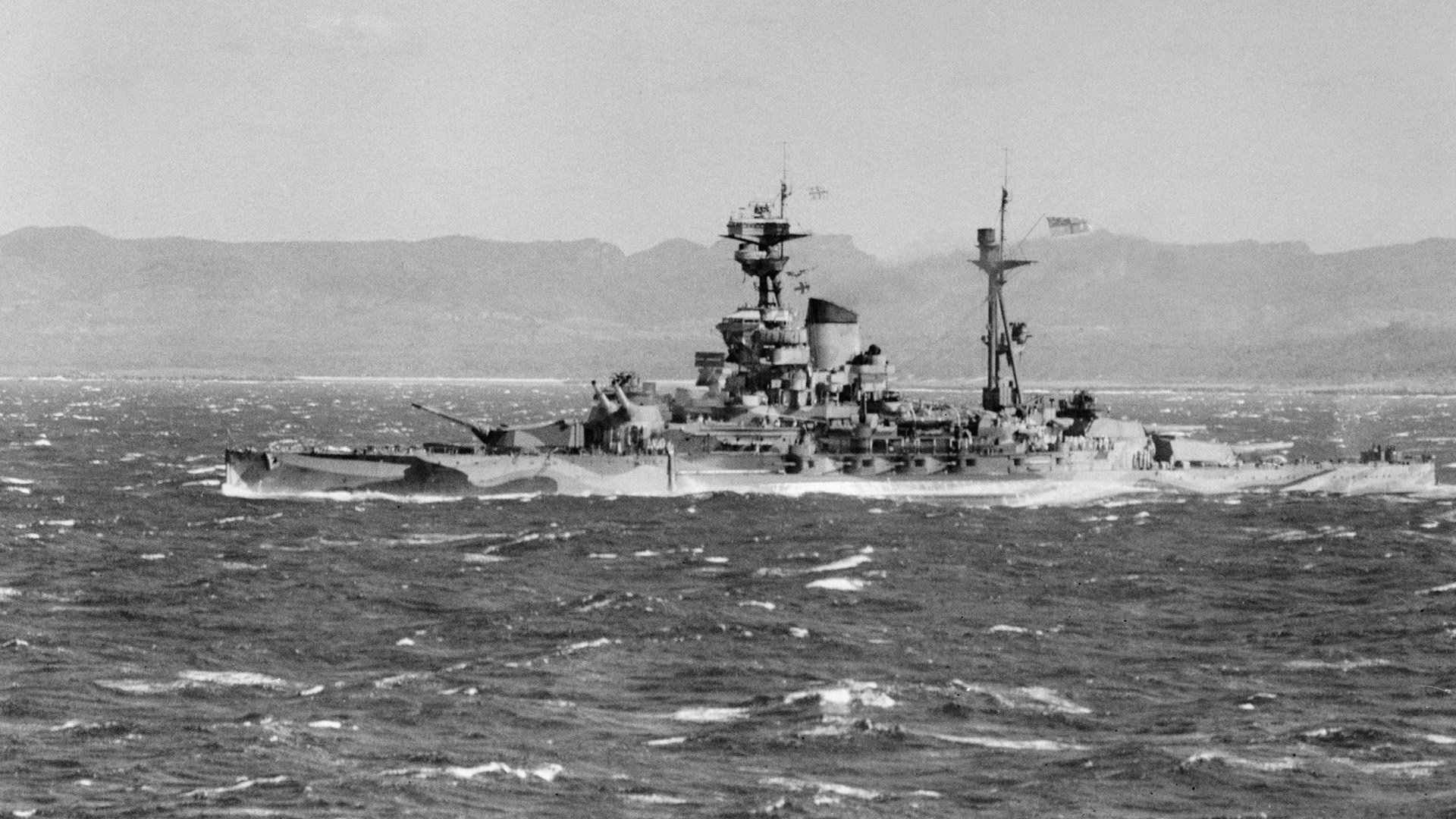

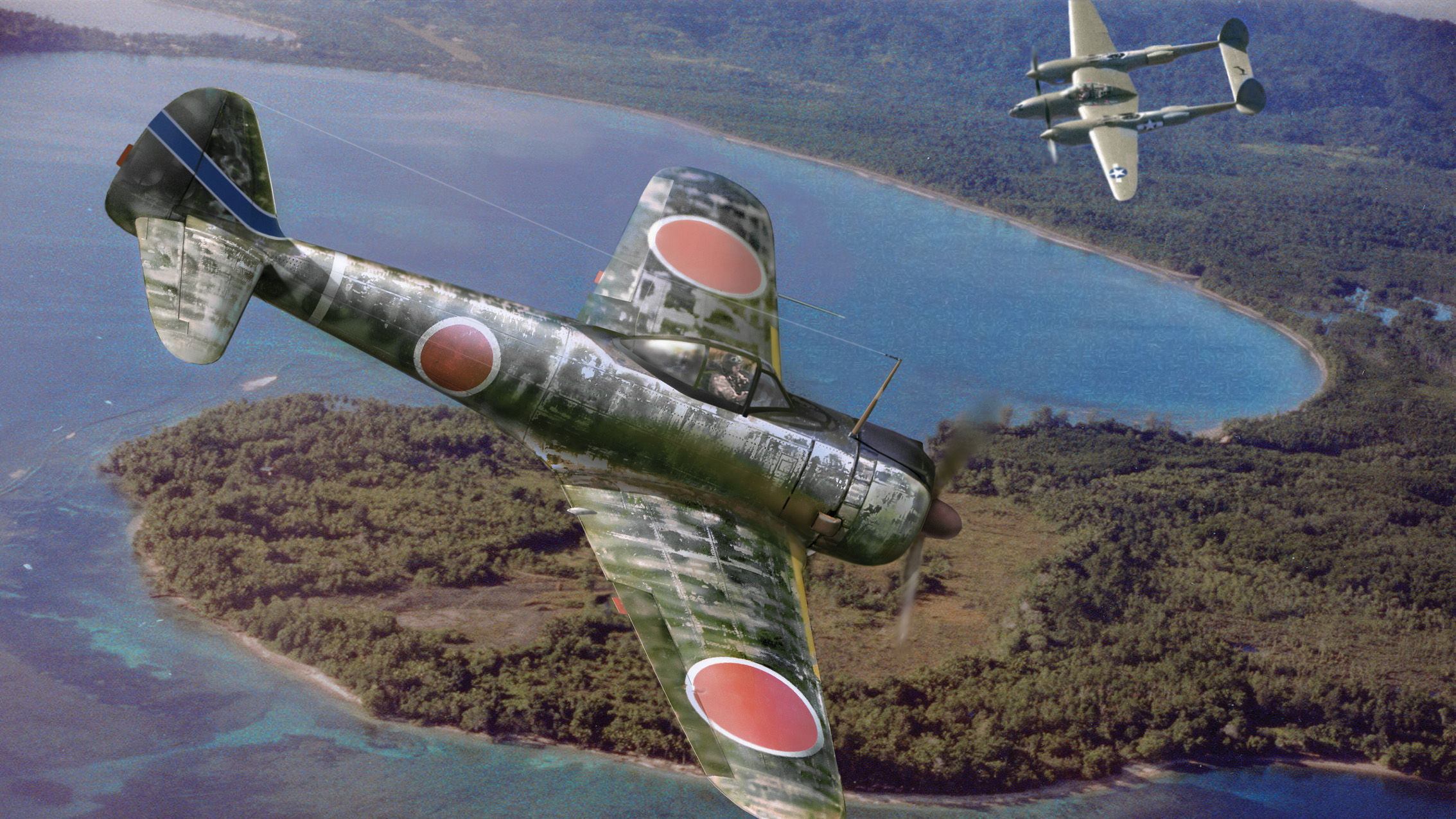

The German U-boat war against Allied shipping was taking a tremendous toll in the North Atlantic. This was largely because of the lack of air cover for the convoys in the mid-Atlantic where the United States’ planes had to turn back for lack of fuel, and the area was also out of range of patrols from Britain. An Allied base in the Azores would (and eventually did) fill this gap, helping to assure safe passage for convoys and menacing U-boats on the prowl.

Diplomatically, Hitler insisted that Portugal refuse the Allies use of the Azores as an airbase. Hitler’s recognition of Portugal’s neutrality would, it was made clear, terminate should Portugal yield to British pressure. The British claimed the right to use the ports under their ancient treaty with Portugal.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt considered taking the Azores by force. By mid-1941, Churchill had urged Roosevelt to assist Britain in preemptively occupying the islands with the pledge to return them to Portuguese sovereignty when the war was over. Although Roosevelt hesitated, in his radio address of May 27, 1941, he informed America:

“Unless the advance of Hitlerism is forcibly checked now, the Western Hemisphere will be within the range of Nazi weapons of destruction…. Equally, the Azores and the Cape Verde Islands, if occupied or controlled by Germany, would directly endanger the freedom of the Atlantic and our own American physical safety … Old-fashioned common sense calls for the use of strategy that will prevent such an enemy from gaining a foothold in the first place.”

Meanwhile, it is clear that at about the same time Hitler’s high command was considering occupying the Azores by autumn of 1941. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, the highest ranking officer in the German Navy, cautiously pointed out to Hitler that the Azores would be extremely difficult to hold in light of the enemy’s air power in the Atlantic.

Antonio de Oliveira Salazar continued to walk a tightrope between the British and American demands, and in accommodation of Hitler and Hitler’s friend, Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, continued to refuse any American or British occupation or use of the islands.

Salazar was an economist from Coimbra University who was recruited as the minister of finance for Portugal in 1926 under the nation’s new leader, Manuel Gomes da Costa. After examining Portugal’s state of affairs, Salazar resigned within only a few days. With rioting in the streets the following year, Salazar was asked to return, which he did on the condition that he be allowed to have a free rein in restructuring the financial affairs of the nation. This included a rigid budget, high taxation of business, and a purging of governmental excess.

Within a short time, Salazar had balanced the Portuguese budget, and by 1930, under the auspices of President Antonio Oscar Fragoso de Carmona, he became the virtual dictator of Portugal. He abolished trade unions and political parties and censored the press. His program was “Deus, Patria, e Familia” (God, Country, and Family). He moved Portugal into the political sphere of Germany, Italy, and Spain, and although he publicly advocated nonintervention during the Spanish Civil War, he clearly favored Franco. Salazar even allowed 18,000 Portuguese to join Franco’s rebels during the war.

After Franco’s victory in Spain, Salazar entered into the March 1939 Pacto Iberico. This agreement was a treaty of friendship and nonaggression between Portugal and Spain, wherein the two pledged to protect their frontiers and agreed to enter into no treaty with any other foreign power that would require aggression against the other.

Unlike Spain and Italy, however, Portugal did not enter into the Anti-Comintern Pact with Germany. In addition, Salazar never compromised or abandoned Portugal’s longstanding alliance with Great Britain. Salazar’s focus throughout the war was to keep Franco and Spain out of the conflict. Salazar assumed, probably rightly so, that an Axis Spain would eventually result in the compromise of Portugal’s independence.

Until 1943, the Azores question remained postponed and deadlocked on all sides. It was finally resolved on August 18, 1943, when an arrangement between Great Britain and Portugal was concluded. Salazar, formally invoking the Anglo-Portugese Alliance of 1373, granted use of the Azores airbase to Great Britain with the proviso that no American presence would be allowed there. This was for German consumption, and the “no Americans” provision was later withdrawn by Lisbon.

Germany was outraged and threatened retribution, although by this time Salazar knew the physical threat that Germany posed to Lisbon was minimal. Still, Salazar placated Germany by assuring the Nazi regime that its shipments of wolframite would continue on schedule. By the end of 1943, Salazar was under considerable Allied pressure to stop the wolframite exports to Germany, and seeing the relative positions of the belligerents at this point in the war, he again acquiesced and stopped the shipments.

Although Salazar garnered much favor with Great Britain and the United States through his compliance with the Allies on these issues, the resolution of the Azores question came late, and it is impossible to estimate the number of Allied lives and the tonnage of Allied shipping that would have been saved had the Allies been able to use the Azores earlier in the war. As for the wolframite, Germany’s lack of this precious substance resulted in a shortage of tungsten steel during the last 11/2 years of the war, and a resultant reduction in the quality of German munitions, especially armor-piercing shells.

On November 28, 1944, Portugal and the United States entered into an agreement with each other to allow the United States to build and use an airbase on the island of Santa Maria in the Azores, and Lisbon allowed the United States to use its Azores bases for many years after the war. By that time, it had become apparent that Salazar and Portugal had managed to survive the greatest armed conflict in history virtually unscathed.

As for Salazar, despite political dissension, electoral challenges, international protest, and several colonial wars, he remained prime minister of Portugal until September 6, 1968, when he suffered a massive stroke and became incapacitated. He died in July 1970, at which time a more or less grateful nation awarded him a magnificent funeral. n

B. Paul Hatcher is a practicing attorney in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He has done extensive research on the neutral nations during WWII and is a contributor to the upcoming Library of Congress World War II Desk Reference.

Both Salazar and Spain’s Franco walked a political tightrope but succeeded in keeping their countries out of the war. This should have left them in better economic condition after WW II compared to the rest of Europe but, unfortunately, both of these men were quite deficient in their knowledge of economics and so their economies languished for over a decade while the rest of Europe recovered. Still, staying out of the conflict was a notable accomplishment.