By Major General Michael Reynolds

The dismemberment of Poland by the German and Soviet armies in September and early October 1939 saw the temporary destruction of the Polish armed forces. Only three destroyers and two submarines reached British ports to continue operations against the Germans. Despite the carnage of the September campaign, many Polish soldiers and civilians managed to make their way to Syria and France via Romania, Hungary and the Baltic States, and by May 1940 some 84,500 Poles were under arms in those countries.

An infantry brigade was sent, as part of an Allied force, to help defend Norway, and two full infantry divisions, two partly organized infantry divisions, and an armored cavalry brigade formed part of the armies defending France. However, in the face of a second blitzkrieg by the seemingly invincible Wehrmacht, the remnants of these divisions, like the British Expeditionary Force, were forced to evacuate continental Europe during June. Only 24,000 Poles reached Great Britain to join hundreds of Polish airmen already there preparing to fight beside their British comrades in the forthcoming Battle of Britain.

Polish Armed Forces in the West

When Hitler made his fatal mistake of invading the Soviet Union in June 1941, Stalin recognized General Wladyslaw Sikorski’s Polish government in exile in London, and a Polish army was formed in Russia for use against the Germans. It was made up of thousands of prisoners of war Stalin had been holding since the 1939 campaign. Then, in 1942, he agreed to transfer a complete corps, under its commander General Wladyslaw Anders, to British command. At the same time, he kept what later amounted to another corps in the Soviet Union to fight on the Eastern Front. This it did with distinction, ending with the final battles for Berlin. The formation transferred to the British, known as the II Polish Corps, completed its training in Iran in 1943, and arrived in Italy in December of that year to fight alongside its British, American, and Canadian allies, most notably in the Battle of Cassino.

The 24,000 or so Poles who reached Great Britain in mid-1940 were quickly reorganized in Scotland to form the I Polish Corps—part of the overall defense forces of the United Kingdom. The corps was made up of the 10th Motorized Cavalry Brigade, the 16th Armored Brigade, and the Independent Highland Rifle Brigade, and it was soon to be reinforced by volunteers from Polish communities all over the world.

By February 1942, the threat of a German invasion had receded and the British agreed to a Polish request that a fully fledged armored division be formed from the existing corps units. General Sikorski, the Polish commander-in-chief and prime minister of the government in exile, appointed General Stanislaw Maczek to command the new division. He was an experienced soldier, having fought in World War I and the Polish-Bolshevik war of 1918–1920, but he had no real experience in armored warfare. Nevertheless, he was a popular leader. One of his most memorable sayings was, “The Polish soldier fights for the freedom of other nations, but dies only for Poland.”

The 1st Polish Armored Division

The new division, known as the 1st Polish Armored Division, comprised two armored brigades, each of six tank battalions, formed from the 10th Motorized Cavalry Brigade and the 16th Armored Brigade; a motorized infantry battalion taken from the Independent Highland Rifle Brigade; a reconnaissance unit; and the normal divisional administrative units. As such, it began collective training and during 1943 conducted several exercises in eastern England.

However, in that year the British decreed that armored divisions should have only one armored brigade; the other major combat component was to be an infantry brigade. The Poles had no option but to conform, and by early 1944 the 10th Armored Cavalry Brigade was made up of three armored regiments (battalions)—the 1st, 2nd, and 24th Lancers—and a mechanized infantry battalion, the 10th Dragoons. Also included were the 3rd Rifle Brigade comprising the Highland (Podhalan) Rifles and the 8th and 9th Rifle Battalions. The 10th Mounted Rifle Regiment (battalion) formed the divisional reconnaissance unit, and two field artillery battalions, one antitank, and one antiaircraft (AA) battalion were in direct support, together with engineer, signals, ordnance, supply, and medical units. The total strength was 885 officers and 15,210 men; equipment included more than 350 tanks, 48 field artillery howitzers, 48 medium and heavy antitank guns, and 54 medium AA guns.

The division was not involved in the D-Day landings or the initial fighting in Normandy, but at the end of July 1944, men and equipment embarked in the port of London and at Southampton. After uneventful voyages, the first Polish troops landed in France on July 30. The men, many of whom had waited four years for a chance to exact revenge on their conquerors, were about to have their battle worthiness severely tested in Operation Totalize, a breakout toward Falaise from the eastern side of the Normandy beachhead.

“The British Decoy Mission Became a Sacrificial One”

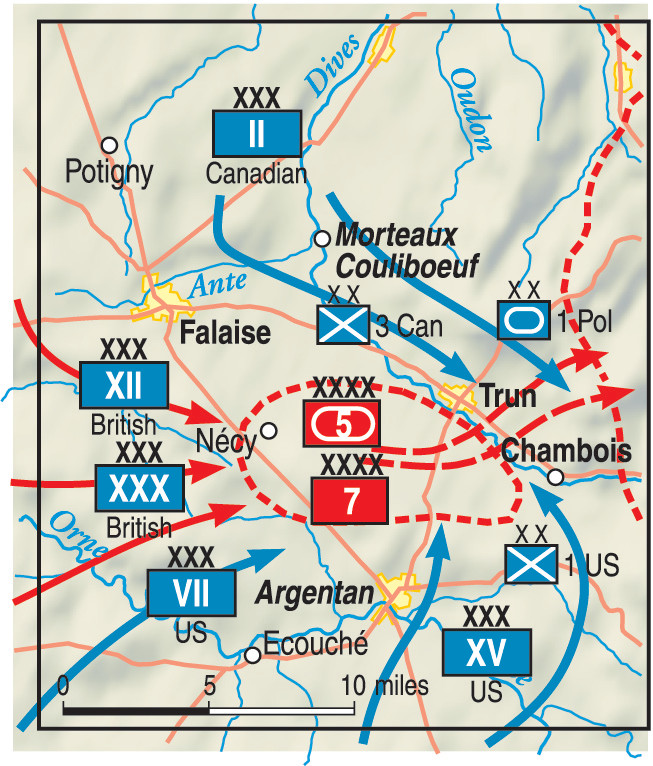

Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s overall strategy of using the British and Canadians to hold the bulk of the German armor on the east flank in order to allow the Americans to break out in the west was working. The British and Canadians on the eastern flank were facing 14 German divisions, of which seven were armored with 600 tanks, while the Americans in the west were opposed by nine hodgepodge divisions, of which only two were armored with a total of just over 100 tanks.

(Above and Top Left: National Archives / Top Right: Author’s Collection)

As the commander of the U.S. Twelfth Army Group, General Omar Bradley, described the situation in his book A Soldier’s Story: “When reckoned in term of national pride, this British decoy mission became a sacrificial one, for while we tramped around the outside flank, the British were to sit in place and pin down Germans.”

The American breakout—Operation Cobra—launched on July 25, was, not surprisingly, highly successful. On August 1, U.S. troops entered Brittany, and the German commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Günther von Kluge, warned Berlin, “The left flank has collapsed.” A day later, Mortain was captured, and on the 3rd Bradley ordered General George S. Patton Jr. to leave minimal forces in Brittany and drive eastward. Rennes was captured on the 4th, and the same day Montgomery issued a new directive that ended, “The broad strategy of the Allied Armies is to swing the right flank towards Paris and force the enemy back to the Seine.” Within two days, Patton’s tanks were approaching Le Mans. It was now time for the British, Canadians, and Poles to begin their breakout toward Falaise.

Another Black August 8 for the Germans

August 8, 1918, marked the beginning of a great British offensive east of Amiens during World War I, which German commander General Erich Ludendorff described later as “the black day of the German Army in the history of the [First World] war.” On the eve of the first major offensive by the First Canadian Army, of which the Poles were now a part, its commander, Lt. Gen. Henry Crerar, told his senior officers that he intended to make August 8, 1944, an even blacker day for the Germans.

The officer given this task was Lt. Gen. Guy Simonds, the commander of II Canadian Corps. He already had his own 2nd and 3rd Canadian Infantry Divisions and the inexperienced 4th Armored Division under command, but he was now given two British formations—the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division and the 33rd Tank Brigade—and the unblooded 1st Polish Armored Division. The latter was destined to play a short but dramatic part in the battle of Normandy.

Simonds brought new ideas to the forthcoming battle. First, he decided to attack at night, without a preliminary bombardment. Second, by removing the 105mm gun from the U.S.-designed M-7 Priest self-propelled artillery vehicle, he created an open-topped armored personnel carrier called the Kangaroo, which gave some of his infantry both mobility and protection. Third, he decided to use Royal Air Force night bombers to saturate the flanks of his proposed penetration and American medium and heavy bombers in the breakout phase after first light.

Such a plan demanded extremely accurate navigation by both airmen and soldiers. A trial was carried out on the night of the 6th, which proved that the artillery could adequately indicate targets with marker shells, and various other technical aids were adopted to help the ground forces, including the use of radio directional beams, artificial moonlight, and tracer fired from AA guns along the flanks.

A Rocky Start for the Offensive

Simonds’s plan was to obliterate the flanking areas of May-sur-Orne–Fontenay-le-Marmion on the right and la Hogue–Secqueville-la-Campagne on the left with RAF heavy bombers starting at 2300 hours on August 7, and then to seize Garcelles, the Cramesnil spur, St. Aignan, Gaumesnil, and the Caillouet features with two infantry divisions. Then, with the aid of a heavy daylight air bombardment, and while the same divisions went on to secure the flanks at Bretteville-sur-Laize on the right and the woods north of Cauvicourt on the left, the 4th Canadian Armored Division was to secure the area Fontaine-le-Pin–Potigny and the 1st Polish Armored Division the vital ground to the east of the Caen–Falaise road on the south side of the Laison stream. Facing this onslaught and sited in depth was General Sepp Dietrich’s I SS Panzer Corps, severely weakened after two months of fighting but still fielding some one hundred 88mm and 75mm antitank weapons.

The 1,020 RAF night bombers began dropping 3,462 tons of bombs on their targets at precisely 2300 hours as planned, and according to the Canadian official history not one bomb fell among friendly troops. Ten aircraft were lost. Then, at 2330 hours the ground assault began and despite considerable confusion caused by the dust created by so many tracked vehicles and exploding shells from the friendly artillery barrage, the new tactics proved a success. By first light the initial objectives had been secured, and by midday Caillouet and Gaumesnil had fallen. Casualties were surprisingly light. All was ready for phase two, in which the Poles would participate with Cauvicourt as their first main objective. However, poor weather forecasts had indicated that the daylight bombers might have difficulty in identifying their targets and so the start time for the advance was delayed until 1355 hours.

Despite some serious delays and some confusion—the Poles, for example, had to move all the way from the Bayeux area during the night—the Allied formations were ready to advance as the first of the 678 American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers approached their targets at 1255 hours. Intense antiaircraft fire shot down nine B-17s, and for various reasons 181 did not carry out their attacks. The remainder dropped 1,487 tons on the three main targets. Unfortunately, tragic mistakes by two 12-plane groups caused an estimated 315 friendly casualties, including 44 Poles, one of whom was the commander of the Divisional AA Artillery Regiment, Lt. Col. O. Eminowicz.

A Halted Allied Advance

The Poles crossed their start line a little precipitately at 1335 hours with their 2nd Armored Regiment on the left and 24th Lancers on the right, each with a company of 10th Dragoons (Motor Battalion) in support. The 1st Polish Armored Division’s operational report records that the 2nd Regiment came under heavy fire from the area two kilometers southeast of St. Aignan at 1425 hours and that the Lancers were under artillery fire. No casualty figures are mentioned.

At 1520 hours, the Polish report says, its 2nd Regiment was in a difficult position with enemy tanks on its left flank, and at 1610 hours II Canadian Corps logged a message from General Maczek’s Headquarters to the effect that 20 Tiger tanks (almost certainly Mk IVs) were “covering with fire all country immediately over” the lateral road through St. Aignan. The Poles had in fact clashed head-on with a German armored counterattack. Obersturmbannführer (Lieutenant Colonel) Hubert Meyer, the chief of staff of the 12th SS Hitlerjugend Panzer Division, claimed later that the Polish 2nd Armored Regiment lost 26 of the 38 Shermans in its two leading squadrons, and since it is known that the regiment received 24 replacement tanks and crews the following day his figure seems very reasonable. With regard to the Lancers, their advance was barred by a shallow valley with a steep southern bank just to the southeast of St. Aignan. This tank obstacle was clearly marked on the 1944 map issued to Allied troops (the original still exists), but had obviously been overlooked by those planning the operation.

This enforced halt not only exposed the Lancers to the artillery fire already mentioned but also to flanking fire from Tigers counterattacking north from Cintheaux. The Germans claimed that the Lancers lost 14 tanks. Certainly, by early evening the Poles had withdrawn to the northwest of St. Aignan. A British gunner in a Sherman tank (and later a distinguished military historian and writer), Ken Tout, witnessed the Polish attack. He wrote later, “We could only watch, admire the Poles’ bravery and be deeply saddened by the losses of our gallant allies. Later, British and Polish medical officers and orderlies tended each other’s wounded.”

The Canadians did little better. It was 1800 hours before the Germans were cleared from the tiny hamlet of Gaumesnil, and there their advance ended. The great armored push had been a dismal failure, and General Simonds was bitterly disappointed. Nevertheless, his plan for August 9 envisaged the Canadians advancing to Point 195, northwest of Potigny, while Colonel Tadeusz Majewski’s 10th Polish Armored Brigade was to seize the area of La Croix and then Point 140 above the Laison stream.

“Tank After Tank Blew up”

The Canadian advance began at 0200 hours but proved a disaster when one armored/ infantry group ended up on the Polish objective—Point 140. It seems, as the unit war diary puts it, “High ground was sighted and we headed for it.” The last radio message from what became an isolated and surrounded group came at 0849 hours, and at 0300 hours the following day only four officers with 44 infantrymen and five tank men escaped to reach Polish lines.

The Poles began their advance on the 9th toward Soignolles and La Croix much later—at 1100 hours. The Cromwell tanks of the 10th Mounted Rifles Armored Reconnaissance Regiment found enemy troops occupying St. Sylvain, and the 1st and 8th Infantry Battalions were tasked with clearing the village. By 1250 hours, the 1st Armored Regiment was on the western outskirts of Cauvicourt and the 24th Lancers were astride a wood 1,000 meters to its southeast. Each had a company of M-10 antitank guns in support. Soon after this they ran into German antitank fire, but by 1600 hours the Lancers had reached the outskirts of La Croix and Point 111 (west), and the 1st Armored Regiment, after passing behind them, was in the area of Point 111 (east), two kilometers northwest of Rouvres. From this position it, perhaps not unreasonably, fired on tanks visible on its next objective, Point 140; however, there was a problem—the tanks, as we have heard, were Canadian.

In addition, German antitank fire had taken a heavy toll of the Polish tanks—one report mentions 22 Shermans being knocked out. Whatever the true figure, the Poles withdrew to the Cauvicourt area. A report by a Canadian officer on Point 140 described how they cheered on the Polish advance, only to see them take severe tank casualties before they were forced to withdraw as “tank after tank blew up and brewed before the disappointed gaze of the doomed garrison.”

The only real success of the day came at 1930 hours when, following a heavy air and artillery bombardment, the 1st Polish (Highland) Infantry Battalion on the left flank began its assault on St. Sylvain. By 2200 hours the village had fallen, and St. Martin des Bois was captured before midnight.

Taking Point 111

General Simonds’s intention for the following day was for the Canadians to seize the high ground at Point 206, just to the west of Potigny, and then exploit toward Falaise, while the 1st Polish Armored Division was to capture the infamous Point 140 and then push on across the Laison to the hills directly north of Falaise on the east of the main highway. However, before there could be any thought of crossing the Laison it was essential to clear the Quesnay woods, and unfortunately for the Allies the Germans had made these woods the center of their whole defense. Maczek strongly resisted an order for his armored division to clear the woods and was proved right when the subsequent attack by a Canadian infantry division failed with 165 casualties, including 44 killed.

Meanwhile, the 3rd Infantry Brigade of the 1st Polish Armored Division under Colonel Marion Wieronski had been due to advance from the Estrées area, but the failure to clear the Quesnay woods combined with intense German artillery and mortar fire caused the attack to be delayed. Eventually, two infantry battalions and the 10th Mounted Rifles Armored Reconnaissance Regiment moved toward Point 111. By last light the Poles were established on the hill—but again only after suffering severe losses. The Germans claimed 18 Cromwell tanks knocked out during this fighting.

On August 11, Field Marshal Montgomery issued a new directive that emphasized the predicament of the Germans in Normandy and the urgent necessity to close the narrowing gap between Falaise and Alençon in order to cut them off. He ordered the First Canadian Army to “Capture Falaise. This is a first priority and it is vital it should be done quickly. The Army will then operate with strong armored and mobile forces to secure Argentan.” However, despite the clear urgency expressed in this directive, that same day Simonds ordered his infantry divisions to relieve the armored divisions. Canadian infantry took over from the Poles on Point 111 that night, and they were placed in corps reserve in the St. Silvain–Cauvicourt area.

Maczek had no illusions about the failure of Totalize. He said later, “From the commanding officer to the lowest rifleman or lancer we had no experience in the art of armored warfare …What experience we had gained in September 1939 in Poland and in June 1940 in France was now obsolete … Experience is not gained in a day, it grows with the passage of months and years.”

On August 13, Montgomery told the First Canadian Army to dominate the Falaise area “in order that no enemy may escape by the roads which pass through, or near it.” He also directed that once the high ground north and east of Falaise had been secured, Simonds’s Corps should exploit southeast and capture Trun as a matter of urgency.

Operation Tractable: An Advance Under Smoke Screen

The plan for Operation Tractable was more or less the same as for Totalize, including heavy aerial bombing. But there was one major difference. It was to be launched in daylight with cover provided by smoke screens. The major blow was to fall on the sector east of the Caen–Falaise highway and was to be struck by two vast armored columns, each comprising one complete armored brigade. These were each to be followed by two infantry brigades. Maczek’s division was given a secondary role. It was to follow up and clear the RAF target areas.

At 1135 hours on August 14, the Canadian guns fired marker shells for the 73 medium bombers, which hit the Germans in the Laison Valley. Five minutes later, the Canadian armored columns began to roll forward, and 12 minutes after that the guns began to lay the thick smoke screen designed to protect the attacking troops. Inevitably, there was chaos as the Shermans tried to negotiate the Laison—one squadron (company) lost 11 of its 19 tanks trying to find its way across. The heavy bombing by 417 RAF Avro Lancasters and 352 Handley-Page Halifaxes commenced at 1400 hours. They dropped 3,723 tons on the right flank of the advance, and although most of the designated targets were hit, 77 aircraft bombed short, causing 397 casualties to the Canadians and 93 to the Poles.

Not surprisingly though, by nightfall the German defense line on the Laison had collapsed. But even then, despite Simonds’s instructions that the armored columns should keep moving at night, they did nothing of the sort and the Germans continued to hold the vital ground north of Falaise.

According to the First Canadian Army operational log dated August 14, some time that day Montgomery ordered Crerar to take the city of Falaise without delay. The only proviso was that this operation was not to interfere with the more important task of capturing Trun and linking up with the Americans coming up from the southwest.

The Slow Canadian Advance

The Canadians renewed their advance on the morning of the 15th, but despite extraordinarily weak forces in front of them they made little progress. Two tank battalions were bloodily repulsed when they tried to move to Hill 159, and it cost 160 casualties to take Point 168 to the southeast of Soulangy. At 1815 hours the town was finally taken, but a strong counterattack pushed the Canadians out and at the end of the day they were back where they started.

But what of the Poles? They finished their task of clearing the RAF target areas, including the Quesnay woods, during the morning of the 15th and then moved to the eastern flank via Rouvres and Maizières. The Germans managed to blow the bridges over the Dives at Vendeuvre and Jort, but by early evening elements of the 10th Mounted Rifles Armored Reconnaissance Regiment, reinforced with a company of M-10s and a motorized infantry company, had forded the river at Jort and moved on to the high ground just to the east of the village.

However, when the 1st Armored Regiment reached the high ground to the west of Jort it mistook the 10th Regiment’s Cromwells for German Mk IVs and opened fire, causing some casualties. The Germans claimed three Polish tanks knocked out and five damaged. Similar attempts to ford the Dives south of Jort and at Vendeuvre failed, but the 9th Polish Infantry Battalion managed to wade the river during the night and establish a bridgehead that was soon reinforced and extended as far south as Barou and the eastern edges of Morteaux-Couliboeuf. However, instead of being allowed to exploit southeastward as the situation demanded—Trun was less than 20 kilometers away—the Poles were told to remain where they were until relieved by Canadian infantry.

On August 16, Simonds issued orders for the Canadians to clear the city of Falaise and for the 4th Canadian and 1st Polish Armored Divisions to cross the Dives and advance southeast from Damblainville and Jort, respectively. Montgomery had telephoned Crerar during the afternoon and warned him that the German divisions west of Argentan would try to break out between Trun and Falaise and that it was therefore vital to seize Trun and close the gap between the Canadians and Americans as quickly as possible.

By now the German retreat was in full swing with men and vehicles streaming back into the surviving salient to the west of the Falaise– Argentan road. Unbelievable targets were beginning to present themselves to the Allied fighter bombers, and it would not be long before artillery and even tanks would be able to participate in the slaughter. Despite Montgomery’s directions, the advance of the First Canadian Army was to be painfully slow.

The attack against Falaise itself by the Canadians was finally launched at 1525 hours on the 16th, and although the northern section of the city was cleared by midnight it was to be the early hours of the 18th before the fighting finally ended.

Successes for the Poles

The Poles did rather better. At 0930 hours on the 17th their 10th Mounted Rifles Armored Reconnaissance Regiment reported a large German column moving east on the Crocy–Trun road and a generally chaotic situation with other German columns, comprising everything from tanks to horsedrawn carts, attempting to escape to the northeast. Even so, one of the Polish reconnaissance squadrons moving in the direction of Trun lost four Cromwells in under a minute to antitank fire in the vicinity of Point 107, two kilometers north of the town. This resulted in the 10th Mounted Rifles halting for the night northwest of Louvières.

In the meantime, a battle group commanded by Lt. Col. Stanislaw Koszutski and made up of the 2nd Armored Regiment, the 8th Infantry Battalion, and a company of antitank guns had been ordered to seize Point 259, while another battle group consisting of the 24th Lancers, 10th Dragoons (Motor Battalion), and an M-10 company was to take the adjacent hills two kilometers south of Grand-Mesnil. This latter battle group was commanded by Major Wladyslaw Zgorzelski, the commanding officer of the dragoons. Point 259, a very large, steep, and thickly wooded feature, was attacked at 1745 hours, and by 2245 hours the Koszutski battle group had completed its task, as had Zgorzelski’s to its north. The rest of the Polish Armored Division closed up during the night.

Montgomery had personally telephoned Crerar’s headquarters early on the afternoon of the 17th to demand more resolute action. His message is recorded in the First Canadian Army war diary as follows: “It is absolutely essential that both Armoured Divisions of II Canadian Corps … close the gap between First Canadian Army and Third US Army. 1st Polish Armoured Division must thrust on past Trun to Chambois at all costs and as quickly as is possible.” Fortunately for the Germans, it was to take another 48 hours for this to happen and for the 10-kilometer gap to be closed. When the Canadians reached Louvières that evening, they inexplicably stopped for the night and made plans to attack Trun the following day.

By now, the Germans were presenting huge targets in the Falaise Pocket. On this day, the aircraft of the Royal Air Force’s 35 Wing reported “a minimum of 2,200 vehicles of all types, including several concentrations so dense as to be uncountable.” Allied aircraft flew 2,029 sorties on the 17th.

By first light on August 18, the bulk of the German Seventh Army had managed to cross the Orne River, and many support and supply units were already east of the Dives. But with the remnants of 13 divisions still inside the pocket, the German retreat toward Vimoutiers had yet to reach full flood.

Allied Advance on the 18th

The combined Canadian and Polish thrust on the 18th, such as it was, came on the east side of the Dives. Despite the urgent order to link up with the Americans at Chambois, the maximum advance on this day was less than 10 kilometers. Although Simonds issued orders that afternoon for one Canadian infantry division to take care of the east bank of the Dives down to Trun and for the armored divisions to push on rapidly to Chambois, there seems to have been little real effort to coordinate the actions of the Canadians and Poles. Indeed, it would appear that at unit level neither had much idea what the other was doing or even trying to do during the critical period of August 18-20. Fortunately for the Germans, many of the Allied intermediate commanders thought the battle was almost over and all they had to do was mop up. Such was not the case, and as a result thousands of Germans escaped to fight another day.

The farthest penetration on the 18th was by a squadron of the Polish Armored Reconnaissance Regiment, which moved through Bourdon and reached the area immediately to the north of Chambois. However, after finding the town well defended and no sign of any other Allied troops, it was ordered back to the area of Point 259. Similarly, a Canadian armored reconnaissance squadron (company) reached the northern outskirts of St. Lambert-sur-Dives at about 1900 hours, but by 2000 hours two of its tanks had been knocked out and it was decided, again fortunately for the Germans, to wait until first light on the 19th to mount a coordinated attack with an a company of infantry. This allowed the Germans to use the bridges in the village during the night without direct interference. Amazingly, and despite the fact that there was no coherent German defense in the area, a complete Canadian armored brigade that had moved to the Trun–Vimoutiers road north of Neauphe by midnight was held inactive in a counterattack role.

What of the main Polish force? The 1st Polish Armored Division operational report states that General Maczek, from his headquarters near Norrey, ordered his Koszutski battle group to make “an immediate stroke at Chambois” at 1930 hours on the 17th. Lt. Col. Koszutski confirmed later that he received this order during his attack on Point 259 on the evening of the 17th but said that he decided to wait for fuel and ammunition before setting off. When he finally gave the order to move, at 0200 hours on the 18th, the fuel and ammunition had still not arrived.

The Auge countryside through which the Koszutski battle group was to advance in fog and at night was broken and hilly, with narrow twisting roads and tracks, few villages, and many scattered farms. Even today, in daylight with a modern map, it is difficult to find one’s way. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that, according to General Maczek, Koszutski employed a local Frenchman to guide his vanguard.

The 2nd Armored Regiment moved off from Point 259 on the correct road, heading east with the men of the 8th Infantry Battalion mounted on Shermans. On reaching the main Trun–Vimoutiers road the leading tanks ran into a German column of motorized and horsedrawn transport and there was a short, sharp engagement in which the Germans suffered badly. The Shermans then continued their move to the southeast in the general direction of Chambois, but shortly after crossing the main road and negotiating a steep hill that caused severe problems for some of the vehicles they mistakenly turned or were misdirected to the northeast and ended up, at 0600 hours, in the area of Les Champeaux, 10 kilometers north of Chambois and nowhere near their objective.

It has been suggested, not unreasonably, that in view of the similarity of the names—Champeaux and Chambois—the guide misunderstood the requirement and led the force to the wrong place. However, suggestions of a misunderstanding about the final objective by the relevant commanders can be discounted. The war diary of the British unit attached to Maczek’s headquarters throughout the campaign and known as “Headquarters No. 4 Liaison, 21st Army Group,” confirms the objective as “Chambois and the high ground to the north-east.”

3, 057 Sorties in One Day

Les Champeaux was, and still is, a tiny hamlet lying on the side of a steep hill and consisting of little more than a church and a half dozen houses. Unfortunately for the Poles, the Germans were occupying the larger village of Hostellerie Faroult, a few hundred meters above and to the northwest of Les Champeaux, on the main Trun–Vimoutiers road. This was being used as a major German escape route. Not surprisingly, there was a sharp clash with casualties to both sides. However, fuel was by now an urgent necessity, and during its enforced wait at Les Champeaux Koszutski’s force suffered further casualties when it was mistakenly struck by American P-47 Thunderbolt fighter bombers attacking German columns on the main road just above them.

Isolated behind German lines, harboring casualties, and unable to move, the battle group was in dire straits. The 1st Polish Armored Division operational report describes the battle group’s situation at this time as “grave.” It goes on to say that the 1st (Highland) Infantry Battalion was sent to help. Maczek’s headquarters later reported “half the petrol being sent to 2nd Armored Regiment was destroyed through bombing just after 1700 hours.”

During this same day the highly experienced Maczek, whose eye for important ground was legendary, decided to block the exits from Chambois by seizing Point 137 near Coudehard and Points 262 (North), 252, and 262 (South) astride Mont Ormel on the main Chambois–Vimoutiers road. With this in mind, the Zgorzelski and 1st Armored Regimental battle groups were also ordered to advance on the 18th, and by 2300 hours they were blocking the Trun–Vimoutiers road and holding the high ground on either side of Ecorches, filling the gap between their compatriots at Les Champeaux and the Canadians near Neauphe.

The division operational report speaks of the Polish battle groups being involved in “heavy fighting with enemy infantry and antitank guns” and of Allied air attacks preventing the 1st Armored Regiment from capturing its objective of Bourdon. Between crossing the Dives on the 16th and last light on the 18th, the Polish Division suffered a further 72 killed and 119 wounded.

Some idea of the scene which had by now developed at Trun was described graphically by one Allied artillery observer: “The floor of the valley was seen to be alive … men marching, cycling and running, columns of horse-drawn transport, motor transport, and as the sun got up, so more targets came to light … It was a gunner’s paradise and everybody took advantage of it … Away on our left was the famous killing ground, and all day the roar of Typhoons went on and fresh columns of smoke obscured the horizon … We could just see one short section of the Argentan–Trun road, some 200 yards in all, on which sector at one time was crowded the whole miniature picture of an army in rout. First a squad of men running, being overtaken by men on bicycles, followed by a limber at a gallop, and the whole being overtaken by a Panther tank crowded with men and doing well up to 30 mph, all with the main idea of getting away as fast as they could.”

Allied aircraft flew 3,057 attack sorties on the 18th.

“Corridor of Death”

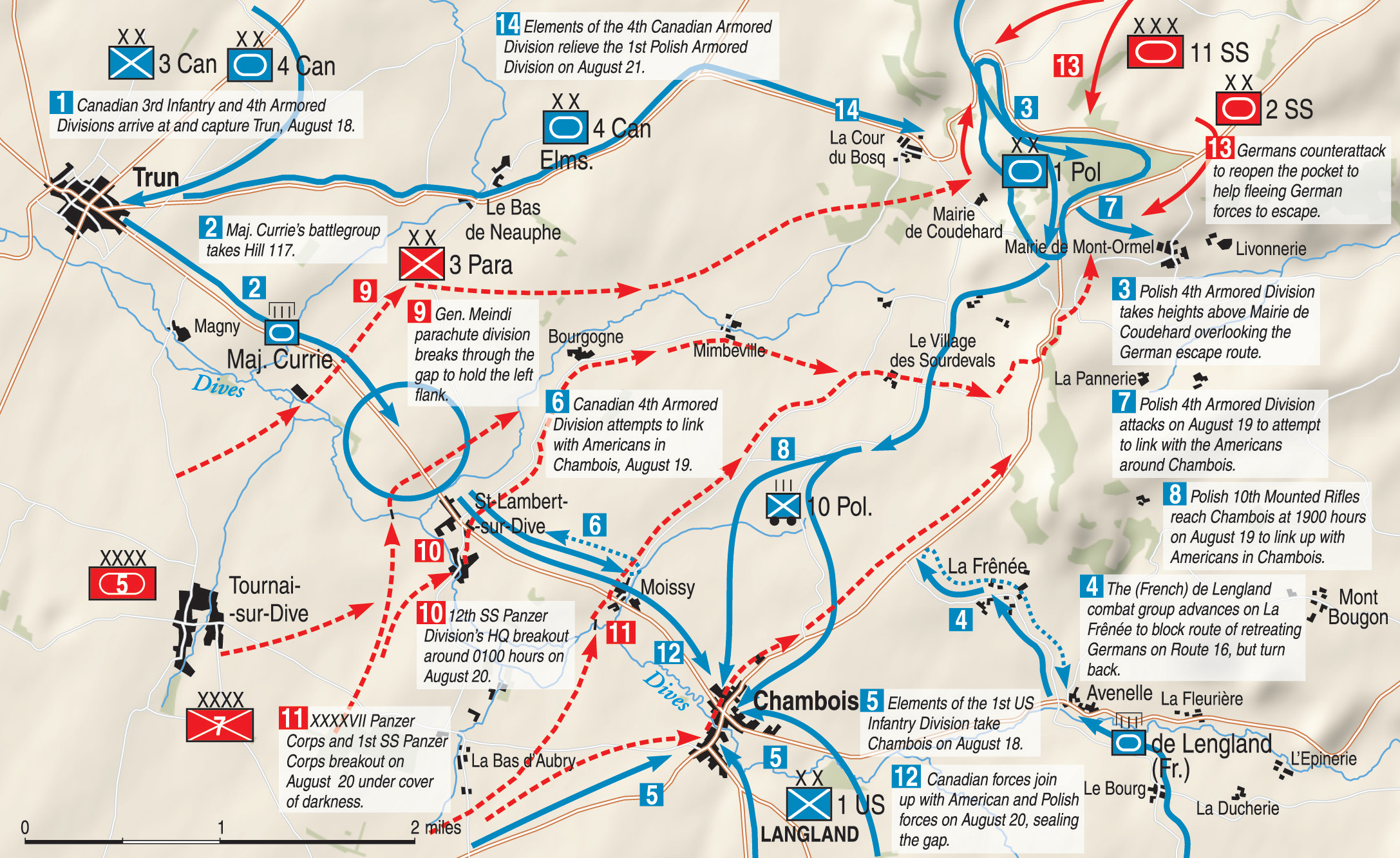

The commander of the German Seventh Army, SS Oberstgruppenführer (Colonel General) Paul Hausser, ordered a final breakout from the Falaise Pocket for the night of 19th. This was designed to link up with a counterattack from outside the pocket by elements of the II SS Panzer Corps (2nd and 9th SS Panzer Divisions). The ordered withdrawal routes were through the St. Lambert sector with the main Dives crossing point halfway between St. Lambert and Chambois at Moissy. This route was soon to earn for itself the unforgettable title of “Corridor of Death.”

Meanwhile, the trap was closing—albeit slowly. Simonds issued further orders at 1100 hours on the 19th. One infantry division was to “strengthen its line and close all escape routes,” and while a Canadian armored division was to cover the river from Trun to Moissy, the Poles would be responsible from Moissy to Chambois and Point 262 (South). Despite these clear orders, action on the ground again failed to reflect the urgency of the situation. Indeed, no Canadian or Polish infantry were moved on to the critical parts of the Dives, and the Allied failure to produce sufficient infantry at the right places was to prove a major blunder. To make matters worse, the Canadian armored brigade to the northeast of Trun remained idle all day. At Simonds’s insistence, and against its commander’s wishes, they were held there as a potential exploitation force for the expected pursuit to the Seine. It was not until the evening that they were told to move toward Vimoutiers.

The only significant Canadian action on the 19th had already started before the corps commander’s new orders were issued. At 0635 hours a company of tanks with a weak company of infantry and a troop of four 17-pounder self-propelled antitank guns mounted an attack on St. Lambert. After six hours of fighting only half the village had been cleared, and despite being reinforced by two more weak infantry companies and eight more antitank guns later in the day, the Canadians could still not secure the southern part of the village. However, they would not give ground and made their famous stand against repeated German counterattacks, earning the group’s commander, Major David Currie, a Victoria Cross. In the meantime, another company of tanks moved to Point 124, two kilometers east of St. Lambert, with the intention of linking up with the Poles.

In accordance with Maczek’s orders, the Zgorzelski battle group secured Point 137, near Coudehard, by midday on the 19th, and the 24th Lancers then moved south toward Frénée. At about the same time, the 1st Polish Armored Regiment with the 9th Infantry Battalion and a company of antitank guns advanced toward the main Chambois–Vimoutiers road at Points 262 (North) and 252, five kilometers northeast of Chambois. This road was being used by the Germans as their main escape route, and when the leading Polish tanks arrived there just before 1600 hours they found it crowded with vehicles, horsedrawn transport, and two Panther tanks—one being towed by the other.

In a short, violent action the Panthers were knocked out and everything in sight destroyed. Then, while one infantry company and some antitank guns occupied Coudehard Boisjos, 700 meters to the northwest, the Shermans and the rest of the infantry and antitank guns took up positions on Point 262 (North). The Chambois–Vimoutiers road was completely blocked with knocked-out vehicles and the bodies of dead men and horses.

The View from the Top of “Maczuga”

By 1030 hours, the Koszutski battle group in the Les Champeaux area had been resupplied, and soon after midday it too set off for Point 262 (North). By 1700 hours it had established positions on the north and east sides of the feature. But while Point 262 (North) and Coudehard Boisjos became a Polish stronghold, no one occupied Point 262 (South).

The position on Point 262 (North) is often referred to as Mont Ormel after the nearby hamlet, but the Poles nicknamed it “Maczuga,” the Mace, after the shape of its contours. From its summit they could enjoy spectacular views over much of the Falaise Pocket—but spectacular views are one thing and controlling the surrounding countryside is quite another. Point 262 (South) and its foothills obscured observation to the southeast, and the steepness of the ground, woods, and hedgerows made control of the ground to the west and southwest with direct-fire weapons difficult by day and impossible at night.

It was through this Coudehard area and Point 137 on the west side of Mont Ormel that many of the Germans (particularly the men of the 1st and 12th SS Panzer Divisions) emerging from the St. Lambert and Moissy crossings would inevitably pass. Fortunately for them, this large Polish force of more than 80 tanks, some 20 antitank guns, and 1,500 infantrymen remained on Maczuga within a perimeter of less than two square kilometers, controlling its immediate environment but little else. Nevertheless, it remained a major, if not the major, impediment to the German retreat.

Since the Poles on Maczuga were physically cut off from their divisional and brigade commanders with Maczek’s divisional headquarters eight kilometers away to the northwest on Point 259 and Colonel Majewski’s 10th Armored Brigade headquarters at Bourdon, three kilometers to the west, the senior unit commander, Lt. Col. Zygmunt Szydlowski, took command. Another serious problem was that the force, now behind German lines, was cut off from its supplies. Despite “strong representations made to Corps HQ on behalf of GOC Polish Armored Division” by the British No. 4 Liaison Unit, the answer came back that no aerial resupply could be arranged before the 21st.

The Allies’ Encirclement Weakens

By 1900 hours on the 19th, the Shermans of the Polish 24th Lancers had advanced to a blocking position 1,500 meters northeast of Chambois, where they linked up with the 10th Mounted Rifles Armored Reconnaissance Regiment and two M-10 antitank companies, which had in the meantime reached the area of Point 113, one kilometer north of Chambois. The most dramatic move on this day, however, came at 1930 hours when the Polish 10th Dragoons, after moving south from Point 137, entered Chambois and shortly afterward linked up with the 2nd Battalion of the American 359th Infantry Regiment. The noose, it seemed, had been drawn tight. But not so!

At the highest level there was a serious lack of coordination, both between the two wings of the Allied armies and within Simonds’s II Corps. At the tactical level there were no Allied troops physically blocking the five kilometers of river between Magny and Moissy (a stretch that could be waded in certain places by men on their feet). The vehicle crossings at Magny, St. Lambert, and Moissy, although heavily interdicted by indirect fire, were still open.

This unsatisfactory situation was further exacerbated when part of the French 2nd Armored Division, which had advanced to Frénée and the Chambois–Vimoutiers road by early evening on the 19th, was withdrawn south of the Dives as darkness fell. Its commander’s eyes were now firmly set on a much more attractive prize—Paris. The region north and northeast of Chambois was, therefore, far from sealed, and the trap was by no means closed.

Allied aircraft flew 2,535 sorties on the 19th, but thereafter the near impossibility of identifying specific ground targets caused the air effort to be switched farther east to the Seine River and its approaches.

The Bloody Defense of Maczuga

On the Allied side there were few significant moves on the 20th. A Polish plan to expand their Mont Ormel bastion by seizing Point 262 (South) was cancelled when strong German attacks began on their perimeter and attempts to get urgently needed supplies through to the beleaguered garrison failed with severe losses. The Poles on Maczuga were now in some difficulty themselves. They had been under fairly intense artillery and mortar fire ever since arriving there 24 hours before, but they were now being attacked from both inside the pocket and from outside by elements of the II SS Panzer Corps. The main attack from outside had started at 0400 hours and was launched on the north side of the Vimoutiers–Trun road.

At the same time, a second attack involving 21 tanks began on the south side. In one incident, five Shermans of the Polish 1st Armored Regiment on Maczuga were picked off in as many minutes by a single Panther firing from Point 239, about 1,500 meters to the north. The Polish situation was worsening by the hour as they were unable to evacuate wounded or prisoners, and ammunition and food were running low. By 1700 hours the Germans had broken into the northern part of the Maczuga perimeter, and it was 1900 hours before they were expelled with the loss of three medium tanks.

In the meantime, at about 1530 hours the Germans had managed to open up another escape route on the east side of the Vimoutiers–Chambois road through Survie and St. Pierre-la-Rivière. The seriousness of this threat caused the Poles to reinforce their motorized infantry in Chambois with tanks of the 24th Lancers.

Early on the 21st, the Polish Armored Reconnaissance Regiment tried to link up with the main force on Maczuga but was fired on by friendly forces and withdrew after two of its Cromwells were damaged. The last German attack against the Poles on Maczuga came at 1100 hours from the west. It was again repelled, but by then the Shermans were almost out of 75mm ammunition. Many of the tanks were immobilized due to lack of fuel and their infantry was exhausted and short of ammunition, food, and water. At 1330 hours, they heard the sound of more tanks approaching and feared the worst.

However, it turned out to be the Canadians bringing relief. They had begun their advance at 0800 hours and lost four tanks on the way while claiming to have knocked out four tanks and two self-propelled guns. The Canadian unit war diary records: “The picture at 262 was the grimmest the Regiment has so far come up against. The Poles had had no supplies for three days; they had several hundred wounded who had not been evacuated; about 700 prisoners lay loosely guarded in a field, the road was blocked by burned out vehicles, both our own and the enemy’s. Unburied dead and parts of them were strewn about by the score … The Poles cried with joy when we arrived and from what they said I doubt if they will ever forget this day and the help we gave them.”

The Poles lost 351 men killed and wounded and 11 Shermans during the bitter fighting on Maczuga.

Closing the Falaise Gap

By 2000 hours Canadian tanks were on Point 262 (South) and others had reached the northern outskirts of Chambois. The gap was finally closed, and the last battle of Normandy was over. Much later on, in November 1945, when addressing the men of the 1st Polish Armored Division, Monty, exaggerating a little, said, “The battle of Chambois was decisive. The Germans were trapped as if in a bottle; you were the cork in that bottle.”

According to official Canadian records, the First Canadian Army suffered 12,659 casualties from August 1-23, 1944, including 7,415 Canadians, 1,374 Poles, and 3,870 British. However, General Maczek claimed later that Polish casualties for August 8-22, 1944, amounted to 1,441 officers and men. Certainly, more than 700 Poles are buried in a beautiful Polish military cemetery at Urville-Langannerie, roughly halfway along the road from Caen to Falaise. Equipment losses in the same period included 66 tanks and 10 antitank guns.

The 1st Polish Armored Division ended the war in the Wilhelmshafen area of northern Germany. By then it had been in action for 283 days, and its total casualties have been estimated at over 5,300 killed and wounded. Tank losses numbered an astonishing 265 Shermans, 51 Cromwells, and 24 Stuarts—almost its entire complement. Members of the division had been awarded one Commander’s Cross, six Gold Crosses, and 349 Silver Crosses of the Order of Virtuti Militari, 16 British Distinguished Service Crosses, 21 British Military Crosses, five British Distinguished Conduct Medals, and 27 British Military Medals.

Winning the War, Losing the Peace

In view of the achievements of General Maczek’s Division, it seems unbelievable that none of its representatives were invited to participate in the victory parade in London in June 1946, but despite protests by some senior British military commanders the postwar Labour government was not prepared to risk offending Stalin. The February 1945 Yalta Conference had redrawn the frontiers of Eastern Europe, and one third of the Polish territories had been ceded to the Soviet Union.

But worse was to follow. On September 6, 1946, the Communist government in Warsaw stripped General Maczek and 75 other Army, Navy and Air Force officers of their Polish nationality, and in the spring of 1947, Britain withdrew its recognition of the Polish government in exile in London. The Polish forces under British command were then demobilized and encouraged to return to Poland. Although the Communist government subsequently issued an amnesty covering those who had fought under British and American command, including the members of the 1st Polish Armored Division, they were in fact considered traitors and some of those who returned, particularly officers, were treated as such.

In the end, and in order to find a legal basis for those who had refused to return to a Communist Poland dominated by the Soviet Union, they were enlisted for two years into a Polish Resettlement Corps under British command. In this they received English language training and were taught skills fitting them for civilian employment. They were eventually allowed to settle in Britain or the countries of the British Commonwealth.

In summary, it can be said that, alone among the Allied powers, the soldiers, sailors, and airmen of Poland helped to win a war but lost the peace.

Michael Reynolds is a retired major general in the British Army, He is a veteran of the Korean War and the former director of NATO’s Military Plans and Policy Division. Reynolds is a recognized expert on the Battle of the Bulge. He initially directed and later appeared as a guest speaker on some 50 British Army and NATO battlefield tours in the Ardennes. Since retiring from the Army, he has written several well-received books on the subject.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments