By Mike Phifer

Kings Mountain was a battle of militia–American Patriots against American Loyalists. Short and intense, it was the last desperate stand of British Major Patrick Ferguson and a turning point in the American Revolution.

After a summer of stirring up the proverbial hornets’ nest in the west of the Carolinas, Ferguson was on the run. Angry American Patriots were gaining on him and his force of 1,125 Loyalist militia as they retreated toward Charlotte, North Carolina, and the safety of British General Lord Cornwallis’ larger army.

On Oct. 6, 1780, Ferguson ordered the supply wagons circled atop a low rocky ridge called Kings Mountain about 30 miles from Charlotte. He was certain it could be defended against the Patriot irregulars pursuing him, but he wrote a letter–his last–to Cornwallis requesting reinforcements that would never come.

The surrender of Charleston on May 12, 1780, had been a devastating blow to the Patriots in the South as 5,700 troops—about half of whom were Continentals—became British prisoners, along with 1,000 sailors. For the British, it was a much-needed victory.

Unable to decisively defeat General George Washington’s Continental army in New England and the Middle Colonies, the British had turned their attention to the Southern Colonies in December 1778. Late that year Lord George Germain, the British Secretary of State for the Colonies, directed Lt. Gen. Henry Clinton, commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, to invade and subjugate the sparsely populated and heavily divided colony of Georgia. Germain hoped that the invasion of Georgia and the Carolinas, together with diversionary attacks in Virginia and Maryland, might bring about the capitulation of the colonies south of the Susquehanna River.

After Clinton captured Georgia, his orders were to turn north and capture South Carolina. Influenced by the former governors of Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, as well as leading Loyalists, Germain believed the majority of colonists in the Southern Colonies were loyal to the crown. But they needed British regulars to support them in their struggle against the Patriots. Clinton, however, was not as optimistic at the prospect, writing that “to bring those poor people forward only exposed them to the resentment and malice of their enemies.” He believed safe havens would have to be secured first, before the Loyalists in the South could be called up.

The British desperately needed the support of Loyalists as the war progressed. France had entered the war in support of the Americans in 1778. This transformed what had been a rebellion in the American colonies into a global conflict. Britain was forced to to transfer troops serving in America to other locations, such as the economically important Caribbean islands. The resulting shortage of troops in North America meant that the British had to rely more heavily on loyal American subjects. Over the course of the long war, thousands of Americans served in military units. They formed 150 Loyalist units, 26 of which were raised in the South.

During the first three years of the war, Tories and Patriots in the Southern Colonies had been engaged in an uninterrupted guerilla war. Clinton dispatched Lt. Col. Archibald Campbell with 3,100 troops, including four Loyalist units, to Georgia in November 1778. They were to join forces with a British and Loyalist force in St. Augustine under Brig. Gen. Augustine Prevost. The first objective of the combined force was to capture Savannah. Campbell landed near Savannah on December 23, but he did not wait for Prevost. He moved quickly against the city and captured it six days later. Prevost then took command and secured the British hold on Georgia, threatening Charleston in May 1779. A force of 5,000 French and Patriot troops under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln and Vice-Admiral Comte D’Estaing arrived in Charleston in September, posing a serious threat to Prevost’s 3,200 troops garrisoning Savannah.

A 7,600-strong Franco-American army co-commanded by D’Estaing and Lincoln besieged Savannah that same month. When the French bombardment failed to produce results, D’Estaing tried to take the city by storm. While Lincoln’s Patriots moved into a blocking position to prevent British overland reinforcements from Florida, D’Estaing landed his French infantry. To D’Estaing’s disappointment, the French assault was repulsed with heavy losses on October 9. Lincoln then withdrew to Charleston and D’Estaing sailed for the West Indies to attack British colonies in the Caribbean.

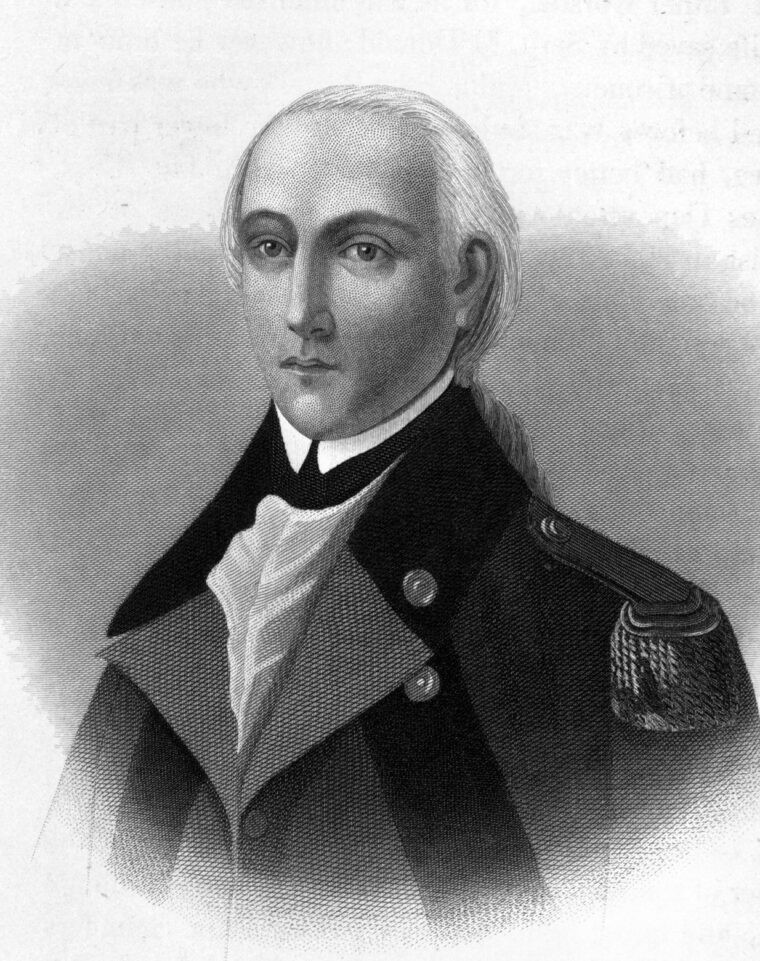

Clinton was elated at Prevost’s successful defense of Savannah. Having withdrawn British troops from Newport, Rhode Island, Clinton sailed from New York on December 26 with 8,700 troops to attack Charleston. Sailing aboard one of the vessels was Ferguson, a Scottish officer in the 71st (Highland) Regiment of Foot. Ferguson was a capable and inventive officer. With the rank of captain, Ferguson arrived in the Thirteen Colonies in 1777 to command 100 riflemen who were armed with an experimental rifle he had designed. Ferguson suffered a severe wound from a musket ball that shattered his right elbow at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777.

With Ferguson out of action, his experimental rifle unit was disbanded. Ferguson eventually recovered from his wound, although he no longer had the use of his right arm. He received a promotion to major in 1779 and assumed command of a detatchment of Loyalist troops raised in New York as the King’s American Regiment, and outfitted like British regulars. Ferguson’s detatchment soon sailed south with their commander.

After a storm-tossed voyage, the bulk of Clinton’s battered ships arrived in Georgia in late January 1780. Over the course of the next 45 days, more scattered ships rejoined the fleet. With British forces swelling to 14,000 troops in the area, Clinton marched against Charleston. His forces moved into positions around the city in March. Clinton had surrounded the city by April 11. His troops then began to construct siege works while British guns shelled the city.

After the surrender of Charleston, on May 12, 1780, Clinton ordered his second-in-command, Lt. Gen. Charles Cornwallis, to pacify the interior of South Carolina. Detachments made mostly of Loyalist troops quickly occupied key towns and posts, one of which was the fort at Ninety Six, located 175 miles northwest of Charleston. Meanwhile, Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton set off in pursuit of a small force of Virginia Continentals that was retreating towards North Carolina.

With mounted infantry and dragoons from his British Legion, a Loyalist unit, and a detachment of the 17th Light Dragoons, Tarleton rode hard after the Patriots. He caught up with the 340 soldiers of Colonel Abraham Buford’s 3rd Virginia Detachment of the Continental Army at Waxhaws on May 29 and charged into their single line of troops. The Continentals got off one volley before many of them were hacked down by sabres or bayoneted. Suffering 260 killed and wounded the Patriots called the battle a massacre as a number of their casualties were inflicted after the cry for quarter was given. “Tarleton’s Quarter” and “Buford’s Quarter” became a rallying cry for many to join the Patriot militia in the coming months.

For the time being however, many men were signing an oath of loyalty to the king. Before the capture of Charleston, Clinton had avoided raising local Loyalist militia until the city was in his hands. He issued a handbill calling up the militia and by the end of May hundreds of men had showed up at Charleston and enlisted. Other areas such as Ninety Six had Loyalists flocking there as well. To install a measure of discipline in the Loyalist militia, Clinton appointed Ferguson inspector of the militia. He also dispatched Ferguson to Ninety Six with his American Volunteers to organize the militia there. At the same time, Clinton made plans to return to New York leaving Cornwallis in charge in the Southern Colonies with 6,400 troops.

Another disaster befell the Patriots in the meantime. American Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates advanced with 3,000 troops on the British base at Camden, South Carolina, defended by Loyalist troops under Colonel Francis Rawdon. Cornwallis rushed north with British regulars and Loyalist militia from Charleston. The two armies met in battle on August 16, and Cornwallis with 2,100 troops inflicted a decisive defeat on Gates, who withdrew with the battered remnants of his army to Hillsboro, North Carolina.

Cornwallis had his eyes on North Carolina and throughout the summer had been preparing to march north once cooler weather arrived. He was quickly to discover, however, that his control over South Carolina was not as strong as he believed. Patriot guerillas under Colonel Thomas Sumter, Colonel Francis Marion, and others conducted swift raids on British supply trains and other targets. To Cornwallis, the region between the Peedee and Santee rivers seemed alive with Rebel partisans.

Unable to crush these partisan bands, Cornwallis believed that the uprisings in South Carolina could only be extinguished by the conquest of North Carolina. If he could not subjugate North Carolina, he believed he would have to give up both South Carolina and Georgia and retire within the walls of Charleston. Cornwallis marched from Camden on September 8 toward Charlotte, North Carolina, his progress slowed by the poor health of many of his troops.

Meanwhile, Ferguson had raised 4,000 men organized into seven militia regiments in the region around Ninety Six. His force included the men of the King’s American Regiment who assisted in training the militia. Throughout the summer Ferguson dispatched detachments that harassed the Patriots, plundering cattle, horses, and food from them while attempting to encourage the Loyalists. At the same time they also battled forces under Patriot militia commanders Isaac Shelby, John Sevier, and Charles McDowell. Shelby and Sevier eventually would take their men back to their settlements over the Blue Ridge Mountains in what is now East Tennessee.

Ferguson had a keen desire to carry the war to the enemy. Lt. Col. Nisbet Balfour, who briefly commanded at Ninety Six, wrote to Cornwallis in June expressing concerns about Ferguson’s rashness. “I find it impossible to trust him out of my sight,” he wrote. “He seems to me to want to carry the war into North Carolina himself at once.” Cornwallis agreed. “I am afraid of his getting to the frontier of North Carolina and playing us some cussed trick,” Cornwallis replied in July.

Despite Cornwallis’ fears, he ordered Ferguson to cover his left flank on his advance to Charlotte. He specifically told Ferguson to make a wide sweep along the western frontier of North Carolina, and continue to recruit militia and suppress the Patriots. Ferguson assured the British commander that his militia were good fighters and could be depended upon to do their duty. Even so, Cornwallis and many of his subordinate commanders still had serious reservations about Ferguson’s abilities.

Ferguson rejoined his command on September 1 after a meeting with Cornwallis at Camden. Not everyone was pleased with Cornwallis’ orders. “[We received the] disagreeable news that we were to be separated from the army, and act on the frontiers with the militia,” Lieutenant Anthony Allaire of the American Regiment wrote in his journal.

Ferguson advanced northwest the next day. Despite his assurances to the locals that he had not come to make war on women and children, Ferguson’s foragers took horses, cattle and provisions from the local population. Ferguson arrived at Gilbert Town, 55 miles west of Charlotte, on September 7 where he established his base of operations.

He then dispatched Samuel Phillips, a Patriot that had been a British prisoner, across the Blue Ridge Mountains with a message to the Overmountain Men. They were American frontiersmen living west of the Appalachian Mountains. They lived along the Watauga, Nolachucky, and Holstein rivers in what is now the northeastern corner of Tennessee. Given that they lived west of the mountains, they were squatters on Cherokee land and in violation of the Proclamation Line of 1763 by which the British sought to keep white settlers off Indian lands. Ferguson warned that if they did not desist from their opposition to the British arms and take protection under his standard, “he would march his army over the mountains, hang their leaders, and lay their country waste with fire and sword.”

Ferguson made a sweep northward. As he did so, his troops skirmished with McDowell’s partisans before returning to Gilbert Town on September 23. Five hundred Loyalists arrived as reinforcements. For the time being, McDowell and his North Carolina militia retreated westward across the mountains.

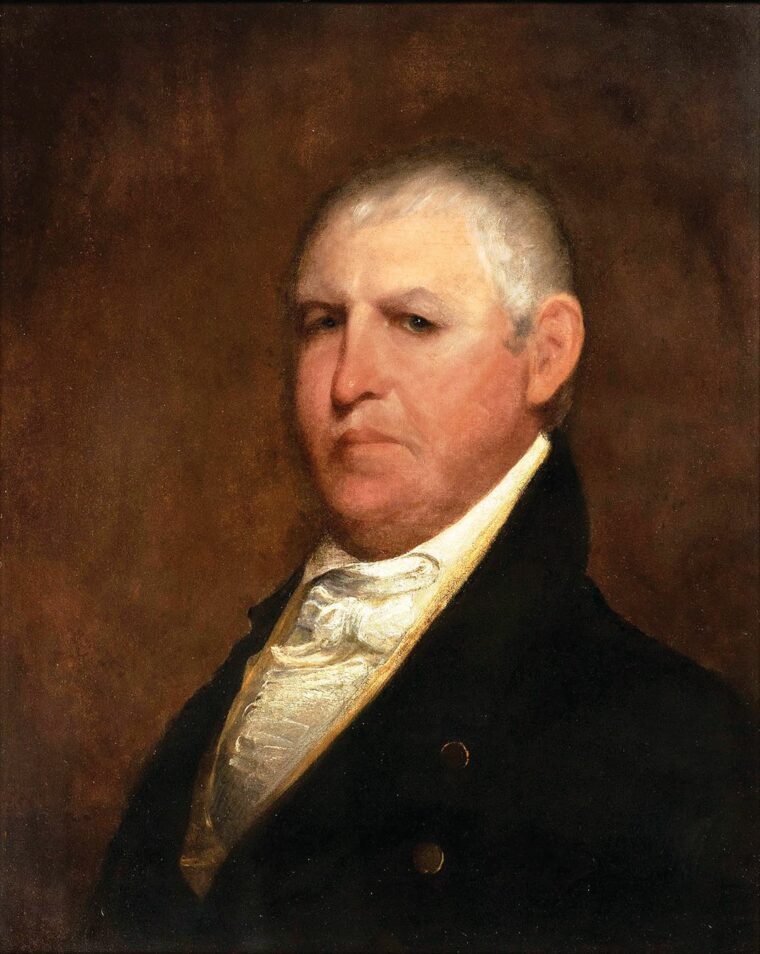

After receiving the message from Ferguson, Shelby and Sevier decided to march with all the men they could muster and launch a surprise attack on Ferguson’s camp. Shelby previously had contacted Colonel William Campbell, a militia commander in Washington County, Virginia, who arrived with 400 men to assist in the attack.

The Patriot force on the frontier began to assemble on September 25 at Sycamore Shoals on the Watauga River. The number of volunteers who turned out, though, was so great that men had to be left behind to protect the settlements from Indian troubles.

The Overmountain Men consisted of Campbell’s 400 men, Shelby’s 240 men from Sullivan County, North Carolina, Sevier’s 240 men from the Washington District of North Carolina, and McDowell’s 140 men from Burke County, North Carolina. A short time earlier, McDowell had ridden back across the mountain to gather intelligence on Ferguson and hurry along 350 troops drawn from the counties of Wilkes and Surry in North Carolina.

These frontiersmen rode toward the mountains on September 26 intending to strike Ferguson first. As they crossed the high mountains, they ran into snow. The men bivouacked by a clear spring and made a startling discovery: two of Sevier’s men had deserted, and the frontiersmen feared the pair would warn Ferguson of the Patriots approach. To avoid the risk of being intercepted by the enemy, the Patriots would need to take a different trail to Quaker’s Meadow where they planned to rendezvous with Colonel Benjamin Cleveland and his Wilkes County militia.

Four days later the frontiersmen reached Quaker’s Meadow having journeyed nearly 100 miles. Cleveland joined the growing army increasing their numbers to 1,400 men. A heavy rain poured over the next day halting the advance of the Overmountain Men and Back Country militia toward Gilbert Town. About this time the senior officers decided they needed an overall commander to lead them. McDowell set off to meet with Gates at his headquarters in Hillsborough with a message requesting ammunition and a capable commander. He left his brother, Joseph McDowell, in charge of his men.

With no word from Gates forthcoming, Shelby proposed Campbell take command. A veteran Continental officer and a judge in his county, Campbell was considered to be good choice as he was a Virginian and less likely to cause resentment among the North Carolinian commanders.

The Patriots arrived at Gilbert Town on October 4 to find Ferguson gone, having earlier moved south and east in an unsuccessful attempt to intercept Lt. Col. Elijah Clarke and his Georgia militia. They did learn that the two deserters had informed Ferguson that the Overmountain Men and Back Country militia were hunting him.

Ferguson had issued a proclamation on October 1 at Denard’s Ford on the Broad River in a desperate attempt to rally support. “Unless you wish to be eat up by an inundation of barbarians, grasp your arms in a moment and run to camp,” he announced. He also sent a dispatch to Lt. Col. John Harris Cruger, the new commander at Ninety Six, requesting reinforcements. As it turned out, Cruger could not spare any men.

Ferguson pushed north of the Broad River with his army, which included a small wagon train, and slowly marched eastward halting on October 3 at a large farm where he remained for two days. He sent a letter two days later to Cornwallis at Charlotte. “I am on my march towards you, by a road leading from Cherokee Ford, north of King’s Mountain,” Ferguson wrote. “Three or four hundred good soldiers, part dragoons, would finish this business.” In the same letter Ferguson implored Cornwallis not to replace him with a superior officer.

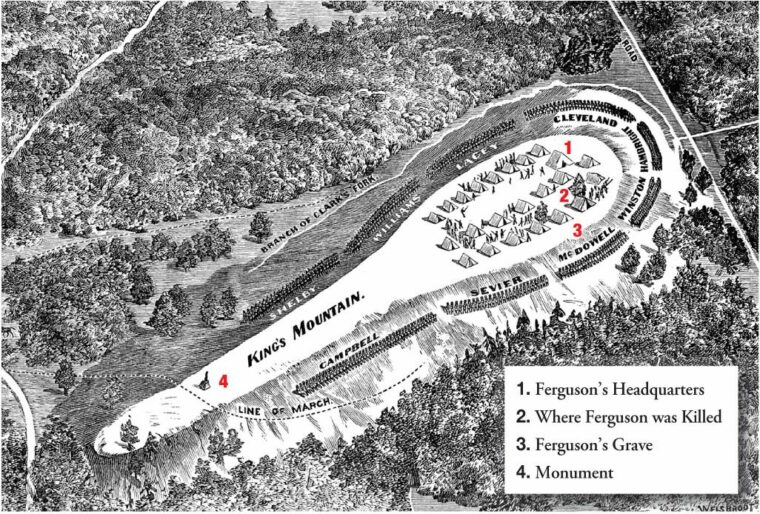

Ferguson broke camp on October 6 and moved his men south, marching crosscountry towards Charlotte 36 miles away. Reaching a series of rocky ridges, Ferguson encamped on King’s Mountain, which was a long, narrow hilltop located a mile south of the North Carolina border. The 600-yard-long ridge, which was shaped like a human foot, rose 75 feet above the surrounding area. The width of the ridge ranged from 60 yards at the narrower southwestern end to 200 yards at the wider northeastern end.

Ferguson ordered men to form their 17 supply wagons into a semicircle at the northeast end of the ridge and pitch their tents there as well. “I have arrived today at King Mountain and have taken post where I do not think I can be forced by a stronger enemy than that against us,” wrote Ferguson to Cornwallis. He was still anxiously awaiting reinforcements, but Cornwallis did not receive his request in time to furnish any.

As for Campbell’s force, it was still attempting to determine Ferguson’s exact location. With their horses and men wearing out, the Patriot leaders on October 5 selected 700 of the best men. They pushed on to Cowpens, South Carolina, which they reached the following day. The Patriot officers had instructed the rest of their men to follow as fast as they could. Four hundred additional partisans joined Campbell’s picked force at Cowpens.

Selecting a fast-marching force of 910 men on the best horses, the Patriots set out again in the rain on the evening of October 6. Riding through the rain, Campbell’s combined force of Overmountain Men and Back Country militia reached the swift-flowing waters of the Broad River by sunrise. After fording the river, some of the leaders believed it best to rest the men and horses, but Shelby would not hear of it. “I will not stop until night, if I follow Ferguson into Cornwallis’ lines,” he said.

By early afternoon the rain had stopped as the frontier Patriots closed in on Ferguson. From Tories they encountered along their route, Campbell and his commanders began to receive information on Ferguson’s position on Kings Mountain. A 14-year-old boy captured carrying a dispatch from Ferguson for Cornwallis revealed the enemy’s position and the fact that Ferguson was wearing a checkered shirt over his uniform. “Mark him with your rifles,” Lt. Col. Frederick Hambright told his men.

Campbell and the other leaders now planned their attack. It was decided they would split into two divisions with one commanded by Shelby and the other Campbell. Shelby’s command would surround the ridge from the north, while Campbell would surround it from the south. Then with their men spread out, an Indian war-whoop would signal them to attack up the steep wooded slopes.

Before setting out, Campbell spoke to each of the units offering any man who was afraid to fight the opportunity to go home. Campbell said he did not want any man who would not fight, but as for himself he “was determined to fight the enemy a week, if need be, to gain the victory.”

“Every man must consider himself an officer, and act from his own judgement,” Cleveland said. “Fire as quick as you can. When you can do no better, get behind trees, or retreat; but I beg you not to run quite off.”

As Campbell’s men were not wearing a regular uniform, many of the Patriots placed a white piece of paper or cloth in their hat to distinguish themselves from many of the Loyalist militia who were not wearing uniforms either. The Loyalists in turn wore green sprigs in their hats.

The Patriots began moving into position to surround Ferguson’s command. Major Joseph Winston and his detachment rode out first intending to circle around the southwest end of the ridge. He was then to double back up the east side of the ridge to block a possible retreat of the Tories to Charlotte.

Ahead of the columns, scouts slipped out moving quietly over rain-soaked fallen leaves to silence Ferguson’s sentries. As the first of these scouts dispatched a sentry, it seemed they would catch Ferguson’s force by surprise. Ferguson had 1,125 men, the bulk consisting of Carolina militia organized into six regiments. Eighty of his 100 American Volunteers were on foot, and the other 20 were mounted dragoons.

Winston and his men believed they had reached their objective. They had dismounted and begun slowly heading up the heights at 2:45 p.m. when they realized they were on the wrong mountain. Winston quickly ordered his men back to their horses and they rode hard to reach their assigned position.

The rest of the Patriots’ advance on King’s Mountain was also running into snags. Shelby’s command was divided into two columns with one under him and the other under Cleveland. The latter’s column began to bog down on the north side of the mountain in marshy terrain a few hundred yards from their objective. Shelby’s column, on the other hand, made better time advancing toward their attack position. Elsewhere Campbell’s command, which included his column, followed by Sevier and McDowell’s column, were still moving into position.

Captain Alexander Chesney, Ferguson’s adjutant, reported to his commander just before 3 p.m. that there was no sign of the enemy and that he had posted pickets on the ridge. The words had barely left his lips when the sound of firing could be heard coming from the pickets. They had spotted Shelby’s column and now any chance of a surprise Patriot attack was gone. Drums began to beat in Ferguson’s camp as his men began to fall in. Ferguson also blew on a silver whistle which he used to call his men.

One of Campbell’s men, meanwhile, stumbled onto a Loyalist picket and was forced to shoot him. The crack of his rifle now alerted Ferguson to Campbell’s position. Campbell now decided to attack, even though not all the various Patriot units were in position yet or the mountain completely surrounded. Campbell ordered Captain Andrew Colville’s mounted detachment to lead the attack.

“Here they are my brave boys, shout like hell and fight like devils!” Campbell shouted to his men. Unleashing a piercing war cry the Overmountain Men surged up the mountain. Captain Abraham De Peyster, Ferguson’s second-in-command, was reminded that he clashed with some of these men in August. “These are the damn yelling boys,” De Peyster told Ferguson.

Colville’s attack was repulsed and his bloodied men retreated back down the heights. Campbell’s dismounted main force pushed on. Sevier’s column was behind Campbell and part of it continued to their assigned position on Campbell’s right. A fair number joined the fight on Campbell’s left. Some of McDowell’s men following behind joined Campbell, while others continued onto their assigned position. “The men of my column, of Campbell’s column, and a great part of Sevier’s, were mingled together in the confusion of the battle,” recalled Shelby.

As Campbell’s men almost reached the mountain’s crest they were greeted by the American Volunteers with glittering bayonets, backed by militia from the region around Ninety Six. The Overmountain Men were sent reeling downhill as the Loyalists charged into them. At the bottom of the hill, Campbell and his officers quickly rallied their men and tried again. They surged back up the heights only to be driven back again by the bayonet. The Patriots then ascended the ridge a third time.

The Loyalists again drove the Overmountain Men back down the hill. De Peyster believed they could have routed the Patriots, but Ferguson already had signalled a retreat. Ferguson was “afraid that then enemy would get possession of the heights from the other side,” De Peyster wrote.

Shelby and his men were also being driven back by Loyalist bayonets. Rallying his men at the bottom of the mountain Shelby shouted, “Now boys, quickly reload your rifles, and let’s advance upon them, and give them another hell of fire!” They were again driven back, but yet again headed back up the hill.

As the fighting raged on, the Patriots were losing formation as small groups of men or individuals pressed uphill. This swarming effect made it hard for the Loyalists to react to the Overmountain Men’s advancing rifle fire.

Leaving the Loyalist militia to deal with the Overmountain Men, De Peyster and the American Volunteers were ordered by Ferguson to move to the northeast end of the plateau. Major Winston and Major William Chronicle finally got their Patriot militiamen in the right position on the northeastern end of the ridge for an attack. At the same time, Cleveland pressed his attack from the north. “We were soon in motion, every man throwing four or five balls in his mouth to prevent thirst, also to be in readiness to reload quick,” wrote James Collins of Chronicle’s detachment.

The Back Country militia struggled up the craggy slopes under enemy fire at 3:30 p.m. but Chronicle was killed by a Loyalist volley. As the Patriots continued to struggle up the heights, the Loyalists launched a bayonet charge at Lt. Col. Hambright’s men on the northeast slope. Staggering under accurate rifle fire, the determined Loyalists drove Hambright’s Back Country militia back down the hill.

Unfazed by the bayonet charge, Hambright’s men were soon moving back up the mountain again. The gritty Patriots now surrounding Ferguson’s command continued to press forward as the fighting intensified. After having a few horses shot out from beneath him, Cleveland fought on foot, urging his men forward.

At the same time, Campbell, Shelby, and Sevier also were encouraging their exhausted Overmountain Men over the summit and to finish the bloody business. “Boys, remember your liberty!” cried Campbell. The Patriots soon reached the crest of the ridge and opened a deadly fire on the Loyalists. The Patriots “took post and opened an irregular but destructive fire from behind trees and cover,” wrote Chesney.

The situation was growing increasingly desperate for Ferguson as the Patriots drove his force into the northeast corner of the ridge. Ferguson’s best troops, the American Volunteers, continued to fight with grim determination. The mounted dragoons launched a desperate charge in an attempt to keep the Patriots at bay, but suffered heavy casualties from Patriot rifle fire. All told, the American Volunteers suffered heavy casualties in the battle.

The Loyalist militia was suffering, too, as they were running dangerously low on ammunition. With his men becoming increasingly unhinged, their commander was running out of options. Ferguson, astride his white charger, attempted to break out of the Patriot encirclement with a small of group of Loyalist officers. Several of Sevier’s men shot him at close range. He slipped from his saddle, but his foot became caught in his stirrup. His horse dragged him around the ridge until some of his officers caught it and lowered their commander’s body to the ground. Some sources say that while on the ground Ferguson attempted to shoot an attacker with his pistol, but was himself shot again and killed.

Command of the Loyalists devolved to De Peyster. He ordered his men to charge, but they informed him they were out of ammunition. The Dutch-American commander raised a flag to surrender in the hope of sparing the lives of the remaining Loyalist troops. A Loyalist officer took the flag and raised it high enough to be seen by the Patriot forces. Yet the killing continued for some time afterwards.

“Our men, who had been scattered in the battle were continually coming up, and continued to fire, without comprehending, in the heat of the moment, what had happened,” wrote Evan Shelby, the younger brother of Colonel Shelby. Knowing that the Loyalists were attempting to surrender, other Patriots shouted references to Buford’s Massacre at Waxhaws five months earlier. “Give them Buford’s Play!” they shouted.

With the Patriots still firing, the Loyalists resumed their fire in the belief that the enemy was not inclined to give them quarter. Shelby put himself in harm’s way by riding between the lines. “If you want quarter, throw down you arms!” he shouted to the Loyalists. Campbell also attempted to stop the carnage by yelling at one of his men taking a bead on the enemy. “It is murder to kill them now, for they have raised a flag,” he shouted.

At the cost of 29 killed and 58 wounded, the Patriots had achieved a decisive victory. The Loyalists suffered losses of 244 killed, 163 wounded, and 700 captured. The tendency of troops on higher ground to overshoot those below them contributed to the difference in casualties. Ferguson’s body was buried on the mountain with his mistress, Virginia Sal, who was killed in the fighting.

A scene of melancholy and distress unfolded the day after the battle. “The wives and children of the poor Tories came in, in great numbers,” wrote Collins. “Their husbands, fathers and brothers lay dead in heaps, while others lay wounded or dying, a melancholy sight indeed.” The dead were poorly buried; as a result, wolves, vultures, and hogs feasted on them in the days to come.

With hundreds of prisoners under his control and the threat of Cornwallis sending Tarleton after them, Campbell desired to depart from Kings Mountain as quickly as possible. After torching the captured wagons, he led his troops north on October 8. “We marched at a rapid rate toward Gilbert’s Town between double lines of mounted Americans,” Chesney wrote.

Cornwallis had no idea of the disaster. He dispatched Tarleton to assist Ferguson on October 10, but by then it was too late. Some of the Loyalists escaped while they were being marched north, while others were slain by their captors.

Campbell became increasingly concerned over these actions. For that reason, he issued an order the following day instructing his men to curtail their cruelty. “I must request the officers of all ranks in the army to endeavor to restrain the disorderly manners of slaughtering and disturbing the prisoners,” the order stated. Despite this, 36 Loyalists were tried at what Chesney deemed a mock trial two days later in which the Patriots hanged nine Loyalists.

After crossing the flooded Catawba River on October 16, the Overmountain Men and Back Country militia dispersed to their homes. Campbell sent the remaining prisoners to the Continental Army garrison at Hillsborough. When he learned of Ferguson’s defeat, Cornwallis withdrew from Charlotte to the relative safety of South Carolina. He shelved his planned invasion of North Carolina for the time being.

The Loyalist cause in the South suffered a major blow at Kings Mountain. “As a consequence of Major Ferguson’s disaster and Lord Cornwallis’s sudden retreat from Charlotte, a general panic and despondency appears to have immediately seized the militia and almost every other loyalist in the province,” wrote Clinton. The British commander-in-chief in North America asserted that Ferguson’s defeat “proved the first link in a chain of events that followed each other in regular succession until they at last ended in the total loss of America.” As such, the Patriot victory at King’s Mountain was a major milestone on the road to the British defeat in the American colonies.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments