By Flint Whitlock

Late on the night of June 5, 1944, while American paratroopers were on their way to drop behind Utah Beach, another, smaller air armada carrying 170 British airborne troops was also dashing headlong into battle like an aerial cavalry charge towards the far eastern flank of the Normandy invasion site.

Only six British Halifax bombers were involved in this phase of Operation Overlord: three from 644 Squadron and three from 298 Squadron. And each was towing a Horsa glider filled with up to 28 superbly trained soldiers.

The six bombers and gliders had taken off from their field at RAF Tarrant Rushton at 10:45 PM on June 5, and now were homing in on their objective in France.

In one of the bombers, navigator Walter Russell Wright recalled, “It was well towards midnight on 5th June. We were flying over the English Channel towards France at about 7,000 feet. Although we could not see them, we knew we were accompanied by five other Halifax bombers, each towing a Horsa. Every so often we felt the drag of the glider as it bumped around in our slipstreams, each time pulling us a little way off course.

“Although we had completed about a dozen operations previously—dropping supplies, weapons and ammunition, and sometimes agents, to the Resistance Movement, mainly in France—we knew this flight to be something special and that the price of failure would be very high. Our task was to deliver six gliders to the vicinity of the bridges spanning the River Orne and the canal running parallel to it.”

Wright knew that the six gliders held 170 officers and men of the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry commanded by 32-year-old Major John Howard. “Their task was to capture and hold those bridges,” Wright said, “to keep them open for the invading British land forces and to deny the Germans their use in any subsequent counterattack. It is said that, at a minimum, failure at what was to become known as Pegasus Bridge, could have made D-Day much more costly to the Allies, and the Airborne Division whose emblem was Pegasus.” At a maximum, failure at the bridge might have meant failure for the invasion as a whole.

For the ten thousandth time, British Army Major John Howard, commanding D Company, 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, ran over his unit’s role in the operation: land in the first of three Horsa gliders as close as possible to the bascule bridge over the Orne Canal, rush the guards, capture the bridge, and hold it against enemy counterattacks until Lord Lovat’s force, the 6th Commandos, landing by sea at Ouistreham, could reach him.

For months Howard and his men had rehearsed every phase of the assault, but he knew that even the best training and best-laid plans rarely survived the first shot being fired.

Three additional gliders carrying the other half of D Company, the Ox and Bucks, under Howard’s second-in-command Captain Brian Priday, would simultaneously be landing 400 yards to the east at the so-called Ranville Bridge over the Orne River in an attempt to grab it also. At this bridge, a Horsa containing Priday and Lieutenant Tony Hooper’s No. 22 Platoon was scheduled to land first, followed seconds later by Lieutenant Tod Sweeney’s No. 23 Platoon and then Lieutenant Dennis Fox’s No. 17 Platoon. Once the two spans were seized, Howard’s men were to send out the coded success signal: “Ham and jam.”

Unlike the paratroops who would be coming in at just a few hundred feet, the first three gliders that were carrying the Orne Canal bridge assault force would detach from their tow planes at 6,000 feet and make a 180-degree circle to approach the landing zones from the south. The other three gliders, assigned to the Ranville bridge, would make a north-south landing.

Lieutenant Tod Sweeney recalled, “As we crossed the coast of France I was leaning in at the door of the [glider] cockpit when the pilot shouted, ‘There you are!’ and in the spotty moonlight I could just see the thin stream of the silver river––and then the two bridges!”

It came time to remove the glider’s door. Sweeney said, “As we went down, my batman got hold of my belt and I got hold of the door and tugged. We’d never done this before in the air because it was a rather dangerous operation. So it took quite a bit of effort to pull the door back and open up. As that happened the glider leaned over, so I found myself looking down on the fields of Normandy at cows munching grass!”

In Sweeney’s number-five glider, pilot Stanley Pearson was doing his best to bring it in on-target close to the Ranville Bridge. “Strange how quiet it all was,” recalled Pearson, “yet the Germans guarding the area must by now have been on the alert. We had glided down to 1,000 feet when the four men in the back started to open the Horsa doors. But they must have slid the doors all the way up, and the glider took a rush of air in the port side door and out the starboard side door, causing the Horsa to swing badly. Speed was still too high. We were now down to 200 feet and opted for the field immediately ahead.”

Major Howard, on the other hand, was right on target: He looked down to see the Orne Canal bridge dead ahead. The anxiety level in his glider was almost thick enough to slice with a bayonet but, as Howard put it, “our enthusiasm to get the job done overcame fear. The landing drill was to link arms with the man on either side of you, then butcher’s grip your fingers, lift your feet and pray that your number wasn’t up.”

Piloting his glider was Manchester-born Staff Sergeant James H. Wallwork, a veteran of the glider assault on Sicily. He recalled, “It was as smooth a flight as any. The troops, encouraged by Howard, sang and, thank goodness, none were airsick, as the design of the Horsa seemed to generate air currents from the back straight to the cockpit, where it seemed to linger.”

Wallwork and his co-pilot, Johnnie Ainsworth, were speeding toward the coast of France, attached to a long rope that connected their Horsa glider, named Lady Irene, to the tail of a Halifax bomber. Six miles from the coast, and at 6,000 feet altitude, Wallwork pulled the lever that cut the glider loose and aimed toward their objective: the cantilevered bridge over the Orne River Canal.

“Thanks to our tug crew,” said Wallwork, “we were dead on time and dead on target, and saw the French coast in plenty of time to get set. Five, four, three, two, one, Cheers! Cast off! Up with the nose to reduce speed whilst turning on to Course One. That was when the singing stopped and the silent flight started. And that was when six Horsas tiptoed quietly into two little fields in Normandy, releasing 180 fighting men in full battle order to give the German garrison the surprise of their lives and a lesson in taking a bridge.”

For three minutes the six gliders swooped down silently on their unsuspecting targets; Wallwork’s glider and the two behind it would land at the canal bridge; the other three would come down 400 yards away at the Orne River Bridge.

Wallwork said, “We could see the twin waterways of the river and canal like silver in the moonlight––which was a little better than half, and more than we had hoped for––and the bridges now showed clearly. It was tempting to fly the rest by the proverbial seat-of-pants, but we resisted and flew the courses and times meticulously. The last leg brought us directly in line with the canal and, behold, the bridge! We were a little high, so half flap and steady in at 90 miles per hour.

“Hold tight!” Wallwork shouted to his passengers as the ground rushed up to meet them. The platoon linked arms, raised their feet off the deck, and waited for impact. Wallwork noted later, and probably somewhat more lightheartedly than he likely felt at the time, “Full flap and touchdown. We streamed the chute, jettisoned it after two seconds, and Ainsworth and I in the nose were now ploughing the field, headed for the embankment. We removed a couple of fences and arrived as required at, or rather in, the embankment. Although we made an awful noise, we seemed not to have bothered the German sentries, who thought perhaps that part of a shot-down bomber had landed.”

The glider touched down and slid at a high rate of speed toward the bridge structure, scraping brush aside and chopping down small trees with a noise that the men feared surely must have been heard in Paris. Finally, the shattered craft stopped with a jolt.

Wallwork noted, “I had taken a header through the Perspex nose and was bleeding from a head cut. It had congealed quickly in my right eye socket, and I thought all night I had only one good eye left. With a black eyepatch, would I look like Errol Flynn? Johnnie was stunned and pinned under the collapsed cockpit, but the troops had traveled fairly well and got on with it. Exactly one minute later, No. 2 arrived and joined in, followed by No. 3, justifying all those ‘Deadstick’ training flights.

“Johnnie revived in a few minutes, and with the aid of a medic I managed to crawl free of the debris, but it required two of us to drag Ainsworth out. Nothing was broken except for one ankle and a badly sprained pair of knees for Johnnie…But I could walk.”

Right behind Wallwork and Ainsworth came glider number two. Riding in it was Birmingham-born Stanley Evans, a 20-year-old corporal in No. 14 Platoon, B Company. “I landed up to my waist in mud,” he recalled, “but we were only about 50 yards from the bridge and we ran straight across.”

As a section commander, Evans’ role was to cover the Café Gondrée, on the western side of the canal, and the area around it. “I could have died loads of times, but Him up above was looking after me. It’s not a question of bravery. In those circumstances, you just do things that you are trained for.” The café would become the company’s aid station.

The rest of Lieutenant Richard “Sandy” Smith’s No. 14 Platoon, 2nd Ox and Bucks, was in the last of the three Horsas to arrive near Pegasus Bridge, slamming to earth at 18 minutes past midnight. The right side of the glider, piloted by Staff Sergeants Boland and Hobbs, was peeled away and several men were thrown from it, one of whom drowned when he was violently ejected and pitched into a nearby pond.

Lieutenant Smith had a particularly harrowing ordeal when he was catapulted from his seat in the fuselage and out through the cockpit windshield. “I went shooting straight past those two pilots, through the whole bloody lot, shot out like a bullet and landed in front of the glider,” he recalled. “I was covered in mud, I had lost my Sten gun, and I didn’t really know what I was bloody doing. Corporal Madge, one of my section commanders, brought me to my senses. He said, ‘Well, what are you waiting for, sir?’”

After shaking the stars from his eyes, Smith found his weapon and, hobbling on an injured knee, led his men to the western end of the bridge where Lieutenant Brotheridge’s No. 1 Platoon was already fighting; German and British bodies littered the bridge, some dead, some wounded. Smith and his men advanced upon a concrete enemy bunker.

“The poor buggers in the bunkers didn’t have much of a chance and we were not taking any prisoners or messing around; we just threw phosphorus grenades down into the dugouts there and anything that moved we shot, said Smith.

Advancing to the west side of the bridge (which would soon acquire the moniker “Pegasus Bridge”), Smith saw a German soldier about to throw a stick grenade in his direction. Smith immediately riddled him with his Sten gun, but the already-primed grenade exploded, a piece of metal hitting the lieutenant in the wrist; although painful, the wound did not prevent him from carrying out his duties or firing his weapon.

Lieutenant Denham Brotheridge’s No. 1 Platoon had been the first to reach the lifting bridge and had overwhelmed the German guards there. They pushed on to the western bank where the Café Gondrée stood; Brotheridge had planned on making it his platoon command post but he never made it that far. Something––a bullet or a shell fragment––ripped into his neck, severing an artery. He fell to the ground outside the café, his life spurting out of the gash.

One of his men, Wally Parr, saw his lieutenant lying in the roadway and went to his aid. Cradling Brotheridge’s head in his hands, all Parr could think was, “What a waste! All the years of training we put in to do this job––it lasted only seconds and he lay there and I thought, ‘My God, what a waste.’” Lieutenant David Woods was also down, three bullets in his leg.

Word quickly spread about Brotheridge’s mortal wound. Major Howard directed Smith to take command of No. 1 Platoon in addition to his own No. 14, and hold the bridge.

Smith continued to lead his men for as long as he could, but with his swollen wrist and bunged-up knee, he eventually had to leave to receive medical treatment.

With bullets still flying, Howard established his command post in the machine-gun bunker at the east end of the bridge. While the battle for Pegasus Bridge was raging, the other half of Howard’s company was coming in for a landing to assault the Ranville bridge over the Orne River; it was a less precise landing than Howard’s.

The lead glider, carrying Captain Priday, was far off course. The tug pilots had somehow overshot the Orne completely and missed the release point and ended up five miles to the east, heading toward Periers-en-Auge and the Dives River. With no one aware of the error, the glider began its descent on the wrong bridge over the wrong waterway.

The second glider, carrying Lieutenant Tod Sweeney and his platoon, came down 500 yards north of the bridge, while the third glider, with Lieutenant Fox and his men on board, landed 900 yards north of the objective. Luckily, their landings were without incident and the men began double-timing south between the canal and river to reach the bridge.

Private Eric Woods of No. 17 Platoon, B Company, recalled, “Our platoon, commanded by Lieutenant Fox, quickly made our way across the fields to our target, a bridge that crossed the river Orne. It was, fortunately, very lightly defended, the main episode being when a phosphorous bomb was hurled at German defenders who were attempting to man a gun position.”

The fight for the Ranville bridge [which would later become known as “Horsa Bridge”] was over almost before it began; what few German guards were there were either quickly killed or run off. With the span now in British hands, the decision was made for Sweeney’s platoon to remain there while Fox and his men continued west to Pegasus Bridge, where the sounds of battle were still ringing, to reinforce Howard and, it was assumed, Brotheridge.

Howard’s men were now in complete control and were rounding up German prisoners and tending to the wounded of both sides. Lieutenants Brotheridge and Wood were carried to a trench that served as an aid station about 75 yards east of the bridge (near where the Pegasus Bridge Museum is today). But there was no one to administer proper care; Captain John Vaughn, the doctor who had accompanied the glider force, was lying unconscious in the mud beside one of the gliders, having been knocked cold during the landing.

Brotheridge soon died from loss of blood. Howard said, “It really shook me, because it was Den and how much of a friend he was, and because my leading platoon was now without an officer. At the top of my mind was the fact that I knew Margaret, his wife, was expecting a baby almost any time.”

But there was no time to grieve; there were two bridges to be held against the expected enemy counterattacks and a battle to be fought and won. Howard’s wireless operator, Corporal Ted Tappenden, was at the radio set, sending out the code words––“ham and jam, ham and jam”–– the announcement that both bridges had been seized. But Tappenden had no idea if anyone was getting the message.

Tappenden’s son recalled years later that his father had told him, “The Major was pleased with the result and, remembering his orders, ‘Hold until relieved,’ at this point turned to my father and ordered him to send the code to the paratroopers that the bridges were captured intact. The code was ‘ham and jam,’ and dad sent the message: ‘Hello Four Dog, ham and jam, ham and jam.’

“He transmitted for some considerable time, unaware that the radio operator he was sending to had been killed when his ‘chute failed to open. After much frustration of not receiving a reply, dad is well remembered for: ‘Hello Four Dog, Hello Four Dog, ham and jam, ham and bloody jam, where the hell are you?’”

There was also a bit of good news. The Royal Engineers sappers under Captain Jock Neilson had crawled under the bridge to check for the demolitions they assumed the Germans had installed to blow the structure sky-high in the event of an attack; no explosives were found.

It didn’t take long for other German units in the area to learn of the British assault on the two bridges and begin preparing to take them back, and soon mortar and artillery rounds began splattering the ground; the paras took cover. At any moment, Howard thought, the Germans would launch their counterattack. Could he hold? And where were the reinforcements he had been promised?

While he waited impatiently for the rest of Brigadier Nigel Poett’s 5th Parachute Brigade and Lt. Col. Richard Geoffrey Pine-Coffin’s 7th Parachute Battalion to arrive by air, Howard set up his defenses around the two Orne bridges. The area east of the Ranville Bridge did not greatly concern him; Poett and Pine-Coffin’s men would soon be dropping there and could set up a stout defense against any incursions coming from the direction of Ranville.

What he worried most about was a counterattack coming from west of the canal. The entire 50-mile stretch, from the Orne Canal to the American airborne area west of the Vire River, was one giant German stronghold. Untold hundreds of German armor and infantry units, plus scores of artillery batteries, were out there in the dark, perhaps even now mounting up and heading toward his tenuous claw-hold on the two bridges. It wouldn’t take much for a superior force to wipe out his tiny, poorly armed group. Howard glanced at the luminous dials of his watch––0026 hours.

Off in the night, Howard’s fears were being realized. In Le Port, just a mile up the road from Bénouville, panzers crews were scrambling to their tanks, starting them, and getting underway. Howard and his men at Pegasus Bridge could hear the sound of engines growing louder, and they expected at any moment to see the steel monsters making a left turn at the T-junction and rumbling toward the bridge.

But the panzers went past the junction and straight into Bénouville. They’ll be back, Howard said to himself, and ordered his men to bring up what few PIAT (small antitank) weapons and Gammon bombs (a type of hand grenade) they had.

Jim Wallwork, his face bloody from his damaged eye, was one of those hauling ammunition and weapons from the shattered gliders. Although injured and half blind, he remembered, “I made myself useful carting ammunition from the glider to the troops, for which effort John Howard thanked me. Politely at first. Then we heard the tank.”

It was true. Fortunately, Fox and his platoon were now arriving at Pegasus Bridge––and not a moment too soon, for the tanks that had passed the T-junction at Bénouville were now on their way back. Howard sent Fox’s men forward then directed Wallwork to go back and retrieve the anti-tank Gammon bombs from Glider No. 1—something the injured pilot was unable to do: “I did not have much joy pottering about in the dark in a damaged glider looking for ammo, and I just could not find those bloody bombs. So I took a case of 0-303 [ammunition] instead, which made [Howard] rather cross.

“‘Get the bloody Gammons!’ he hollered, all politeness now gone. So back I went again. This time I was using my flashlight to be sure they were either there or not when I heard a sharp rapid tapping on the wooden fuselage just above me. Woodpeckers? At night? In a battle? No. It was a German Schmeisser following the stupid clot who’s using a flashlight! So to hell with Howard and his Gammons. I had had enough, and told him so. It turned out they had been part of the discarded equipment back at Tarrant.”

The German tanks came on. Private Eric Woods noted, “One of my most vivid memories on reaching [Pegasus] bridge was finding myself lying alongside Sergeant [Charles] Thornton, who was armed with an anti-tank weapon. On the road on the opposite side of the bridge was a junction and from there emerged three French tanks which had been commandeered by the Germans.”

From a range of about 30 yards, Thornton sighted the PIAT and fired, “hitting the foremost tank broadside on. It must have been a direct hit on the tank’s magazine, for there was an almighty explosion and ammunition continued to explode for more than an hour afterwards. The two remaining tanks quickly retreated from whence they came.”

A German staff car and motorcycle then came barreling up the road and ran into a British ambush. Woods vividly recalled seeing “a German motorcyclist…blown off his machine during the fight; his legs were severely injured. A German officer was also at the scene and immediately surrendered to me, passing over his revolver.

“He was most concerned about his wounded colleague and in very good English, asked for medical assistance, saying, ‘I don’t think you would want to leave one of your mates in this condition, would you?’ I assured him that I would return to his comrade with medical assistance as soon as he had accompanied me to surrender himself to a British officer, which he did. I returned and a corporal helped me to get the wretched man to the medics.”

With Howard’s men having killed, captured, or run off the German guards, and with the two other panzers unwilling to charge the bridge in the dark, the British were in complete control of the lifting bridge and the immediate area, and the situation at Pegasus Bridge had become stabilized, at least for the moment; the probing German tank commanders at the T-junction in Bénouville, not knowing the size of the British force, pulled back, leaving their lead tank to burn and explode and sizzle.

From near the burning tank there came the moaning sounds of someone in agony. Fox said that one of his men, Tommy Klare, “couldn’t stand it any longer and he went straight out up to the tank and it was blazing away and he found the driver had got out of the tank still conscious, was laying beside it, but both legs were gone.”

An extremely strong soldier, Klare picked up the wounded German, threw him over his shoulder, and carried him back to the aid station. “I thought it was useless, of course,” said Fox, “but, in fact, I believe the man lived.” The German, the commander of the 1st Panzer Engineering Company, however, died a few hours later.

At about ten minutes till one, the low, droning sound of a large number of aircraft engines mingled with the crump and crash of mortars and artillery, and Major John Howard knew that the airplane noise signaled the imminent arrival of more paratroops––elements of Brigadier Nigel Poett’s 5th Parachute Brigade and Lt. Col. Richard Geoffrey Pine-Coffin’s 7th Parachute Battalion, getting set to jump over DZ “N,” just east of the Ranville Bridge. It was one of the day’s more accurate drops, although not without mishap.

Major Bill Collingwood, the jumpmaster in his plane, was standing over the exit hole of the Albemarle waiting for the green light when suddenly the plane was rocked by a German shell. Collingwood fell out the hole and his static line became wrapped around his leg, dangling him beneath the craft like a fish on a line and slamming him around violently in the hundred-miles-per-hour slipstream. Someone at the back of the stick yelled, “Cut the bugger loose,” but the number-two man, Private Dan Collis, threatened to shoot anyone who tried. Eventually, the men of the stick managed to pull the shaken major back into the plane. The men jumped but Collingwood and the crew flew back to RAF Odiham, where he immediately found a ride in the next wave of paratroops leaving for France.

There were also lighter moments. Lieutenant Nick Archdale of the 7th Parachute Battalion recalled, “We weren’t over the coast a minute or two. Just before I jumped I threw out a stuffed moose head which we’d purloined from a pub in Exeter and was planned to put the fear of God into any German it hit! Then out we went.”

Brigadier James Hill, commander of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, was jumping with his brigade and also had an odd gift for the Germans. “In camp, to keep the Canadians amused, I’d had a football with Hitler’s face on it in luminous paint. Everyone knew I was proposing to drop this, along with three bricks, which they gave me with some rather vulgar wording painted on them, onto the beach to astonish the enemy. So there I was, as brigade commander, standing in the door of the aeroplane with a football and three bricks! As we got over the beaches, out went the football and the bricks and myself.”

Hill landed in one of the flooded areas. “I had tea-bags sewn into the top of my battledress trousers, so while I was trying to get out of this lake I was just making cold tea! The way we got out was that we each had six-foot ropes with a wooden handle at each end for tying things up. As we met up with others, we linked up with these toggle ropes because if you went into a deep ditch and you weren’t tied to someone, you drowned, and there were many drowned that night. After a four-hour struggle we got out, more or less on the edge of our DZ.”

Bricks, soccer balls, and moose heads weren’t the only unusual things that were dropping into Normandy on D-Day. A number of “para-dogs” were also making the trip. Trained to jump from aircraft with their handlers, these animals were called upon to undertake guard, mine-detecting, and patrol duties once on the ground. Their acute hearing and sense of smell provided an “early-warning system” that undoubtedly saved many lives. While a number of the dogs were used by SAS teams, several also accompanied 6th Airborne forces.

One of the most well known of the para-dogs was Bing, a German Shepherd, assigned to the Scout Platoon of Lt. Col. Peter J. Luard’s 13th Parachute Battalion, which used several dogs––Bing, Flash, Monty, Ranee, and Bob, the latter a captured German dog. It is not known how much, if at all, the dogs enjoyed parachuting. Some seemed enthusiastic, but Bing sometimes had to be encouraged to jump with a helpful nudge to his rear. Several of the dogs were dropped into Normandy in June 1944, and later over the Rhine in March 1945. Bing landed in a tree in Normandy and remained hung up there all night. The animal was a pitiful sight, badly wounded in the neck and eyes. But once he was released from his parachute, he stood guard uncomplainingly at a vital section of the battalion’s front.

The Canadians also had a para-dog, one named Johnny that jumped into Normandy with his handler Peter Kawalski. Otway’s 9th Para also had a para-trained German Shepherd––Glen. He and his handler, nineteen-year-old Private Emile Servais Corteil of Watford, Hertfordshire, A Company, 9th Para, took part in the Normandy landings. Sadly, both Corteil and Glen were killed on D-Day. (Corteil is buried at the Ranville British War Cemetery, with Glen at his side. Bing was awarded the Dickin Medal for his service––the animal equivalent to the Victoria Cross––an award that provided recognition for the animal’s gallantry and devotion to duty.)

At the Orne bridges, as Howard and his men listened to the growing roar of airplane engines overhead, they smiled at the thought that soon reinforcements would be reaching them. An impressive number of British troops––over 2,000 of them––would soon arrive in the eastern invasion area.

The 7th Para jumped. Captain Richard Todd recalled, “Although I had 40 jumps under my belt, I had no experience of dropping under fire. But I remember looking out and seeing the tracer bullets zipping past us. I thought what a pretty sight it was with all the coloured lights. I didn’t think about the risk to my life––I just jumped.”

A few seconds later, he crashed down in a cornfield a half mile from the bridge with German gunfire ripping the air around him. “As soon as we were on the ground our dropping zone was covered with enemy fire. Being first out of the first plane wasn’t my idea, I assure you, but immediately I could see I was lucky. My plane had benefited from the element of surprise.

“We’d come under a lot of enemy fire but nothing compared to the flak the other planes behind were getting. Looking up I saw whole planes full of paratroopers being brought down. We lost a lot of men that way. One, Tony Bowler, was one of my closest friends. Tony’s plane was one of those that came down, complete with all its 20 paratroopers.”

Todd decided that hanging around on the DZ was definitely unhealthy, and so he started off. “Luckily I dropped right by a track that led straight to our rendezvous,” he said.

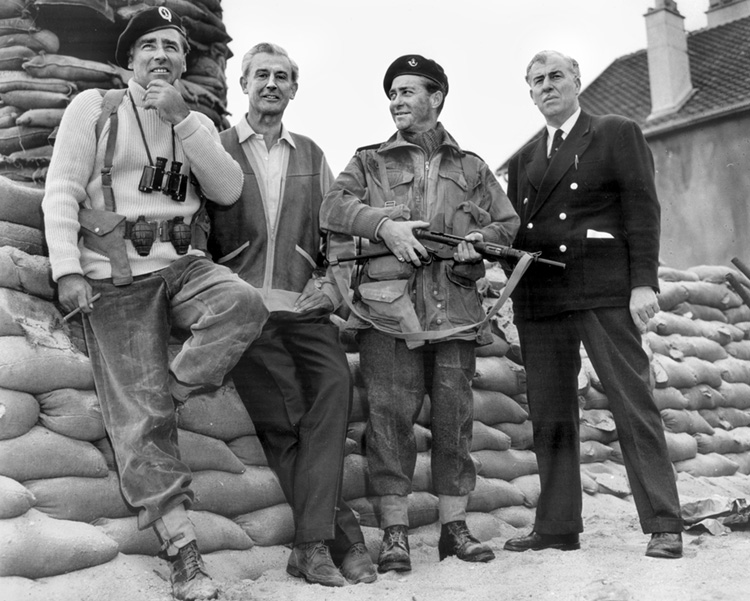

(Interestingly, Todd became an actor and played the part of Major Howard in the 1962 film, The Longest Day.)

Gathering the just-arrived paras into some semblance of a fighting organization was now the next problem for unit commanders. To solve it, many of them had brought with them English hunting horns––little brass instruments traditionally used by the gentry on their horse-mounted fox hunts to rally the hounds and excite them for the chase. Now these same bleating horns were used to rally the troops and excite them for battle.

As Cornelius Ryan noted in The Longest Day, “Across the moonlit fields of Normandy rolled the hoarse haunting notes of an English hunting horn. The sound hung in the air, lonely, incongruous. Again and again the horn sounded.” The camouflaged paratroops rallied to the sound and prepared to march into battle.

The roar of the planes faded off into the dark as the plaintive calls of the hunting horns rang faintly in the damp air. At the Ranville bridge, Major Howard breathed a sign of relief when he saw Brigadier Poett’s tall figure striding toward him out of the dark with one man; the rest of Lt. Col. Richard Geoffrey Pine-Coffin’s 7th Para was some distance behind, the victims of an inaccurate drop.

Pine-Coffin had made it to the rendezvous point, only to find but a portion of his battalion assembled there. Realizing that half a battalion was better than none, Pine-Coffin set off with the force for the bridges; the 7th would arrive at about 1:40 AM. The battalion commander noted, “Many of the Battalion got their first sight of a dead German on that bit of road and few will forget it in a hurry, particularly the one who had been hit with a tank-busting bomb whilst riding a bicycle. He was not a pretty sight.”

There were more gruesome scenes along the way. Richard Todd recalled seeing the corpse of a German officer torn in half near his staff car, along with his driver. “It was the first time I’d seen a shattered dead body like that,” admitted Todd. “I remember thinking, ‘Poor sod.’ It meant no more than that.”

The medical officer caught up to Todd on the march and asked, “Can I come with you? You see, I’m not used to this sort of thing.” Todd noted that the doctor was a bit unnerved after having seen “a German with his head shot off, but his arms and legs were still waving about and strange noises were coming out of him.”

With bullets and shells whizzing over the battalion as it double-timed down the road, Major Nigel Taylor, commanding 7th Para’s lead company, was as relieved to arrive at the bridge as Howard was to see him. After Howard briefed Taylor on the situation, the latter deployed half of his company into Bénouville while Todd took his platoon to Le Port to block the road from Ouistreham.

“It was a rough night,” recalled injured glider pilot Jim Wallwork. “We pilots did what little we could, and although we were not normally chummy with the Parachute Brigade, we made them very welcome about 0300 hours that night. We did mention their rather late arrival and said that the battle was won, though neither was true.”

By 3 AM, the expected German counterattack still had not materialized. Except for the tank at the T–junction that was still cooking off, everything was relatively quiet. Then Howard received a radio message from Tod Sweeney that Pine-Coffin and his advance party were approaching the Ranville bridge from LZ “W.” Howard went out to meet him and brief him on the situation.

Pine-Coffin then moved into Bénouville and set up his headquarters at the Café Gondrée; an aid station was also established there. Howard pulled D Company back from the perimeter and assembled the men between the two bridges where they could serve as a reserve company if needed.

The German counterattack that the British kept anticipating did not occur, although harassing mortar and sniper fire regularly kept the paras’ heads down. In the meantime, some of the paras had figured out how to fire the anti-tank gun in a concrete pit next to the bridge, and launched a few shots at a nearby concrete water tower from which sniper fire was coming.

During the morning a flight of Spitfires flew over the bridges and, noting that recognition panels had been spread out on the ground to indicate that the area was in British hands, did a few victory rolls. One of the planes made a pass and the paras saw some sort of object dropped from it.

After going out to retrieve it, they discovered it was a bundle of that morning’s London newspapers. Hoping that the papers would be full of detailed news about the invasion and the decisive roll played by D Company, 2nd Ox and Bucks, the men groaned with disappointment that the invasion was not even mentioned.

A number of other gliders had been coming into Normandy in the darkness to deliver supplies, weapons, vehicles, and additional troops. The largest lift consisted of 68 Horsas carrying elements of the 6th Airborne, along with four Hamilcars packed with heavy equipment; 47 of the Horsas and two of the Hamilcars eventually landed in France.

One of the Horsas held General Richard Gale, commanding officer of the 6th British Parachute Division. His glider made a safe, if bumpy, landing and collided with a hedgerow. There were no injuries, but Gale’s jeep could not be extracted, so he and his staff began walking to the Château du Heaume at Le Bas de Ranville, where he had chosen to establish division headquarters.

Along the way, Gale found transportation: a horse grazing in an open field. It was on horseback that he encountered Brigadier Poett, who informed him that 5th Brigade had achieved all its early objectives. D-Day in the British sector was apparently off to a fine start.

An even larger lift took place during daylight on D-Day, when 250 gliders carrying 7,000 men of Hugh Kindersley’s 6th Air-Landing Brigade were towed to Normandy. Any German soldiers viewing this aerial spectacle must have been in awe while shaking in their hob-nailed boots.

It was now 7 AM, June 6––the time that the paratroops had been told the seaborne forces would begin attacking Gold, Juno, and Sword beaches, but no battle sounds could be heard from the coast, three miles to the north.

Pine-Coffin noted, “We had overlooked the fact that H-Hour, 7:00 AM, was the time at which the guns would be fired and not the moment when we would hear the explosion of shells. Actually, the ships were some distance out in the Channel and the shells took a measurable time themselves to reach their targets and the sound of the explosions took further time to travel the three odd miles to battle position. It was a full minute after seven when the sound was heard.

“The noise, when it came, far exceeded all expectations and was quite indescribable both in intensity and duration, but it was music to the battalion, and spirits rose with the rumbling of it. The sense of fighting a lone battle passed completely; even fatigue was forgotten. The big show had begun and now it would only be a matter of time before the seaborne troops arrived on the scene and the battle for the bridge could be regarded as completely won.”

To show his gratitude for the liberation of his home and homeland, Georges Gondrée went out into the garden behind his café on D-Day and dug up 98 bottles of champagne that he had buried in June 1940 to keep them from the Germans. Very soon the scene at the café was one of great celebration as Monsieur Gondrée began pouring free champagne for all the Brit paras.

Upon hearing of this, Howard ordered all of D Company to report sick at the aid station in the café so that they could get their well-deserved reward. Georges continued to serve complimentary drinks to the British troops throughout the day until the bottles ran dry.

German snipers remained a constant menace throughout D-Day, especially once daylight came and made it easier for the marksmen to see their targets. Pine-Coffin noted, “The part of Le Port nearest the canal was never completely cleared of snipers who made life a precarious affair in the area of Battalion Headquarters. As soon as one was cleared from one place, others would appear elsewhere, even to return to the same place.

“They were not very original although their courage could not be denied. The church tower was a particularly popular spot and was undoubtedly a first-class choice, if rather an obvious one on the part of the sniper to use it. No sooner had one been silenced, usually with a Bren gun, than another would start from the same place.”

There was more good news as morning turned to afternoon. Private Eric Woods was on guard near Pegasus Bridge when, from off in the distance, came the faint skirl of bagpipes. He turned to a fellow soldier. “Do the Germans play the bagpipes?” he asked.

“I don’t think so,” said his mate.

The sound of the pipes grew louder as the Green Berets of Lord Lovat’s force, advancing from Sword Beach, neared Pegasus Bridge at about 1 PM. The pipes were being played by Bill Millin, and he had played them off and on ever since their landing craft came ashore at Ouistreham, even while under enemy fire.

The story of the Commandos’ and Lord Lovat’s arrival at Pegasus has been surrounded in myth, probably perpetuated by the movie, The Longest Day. Historian Neil Barber, author of The Day the Devils Dropped In, noted, “Lovat [AKA Simon Christopher Joseph Fraser] did not lead the first Commandos to link up with the Airborne Forces in Le Port [north of Bénouville]. This honour fell to No. 3 Troop of 6 Commando, led by Captain Alan Pyman.”

Barber said that many accounts of Lovat’s arrival have him apologizing for being two minutes late. In correcting this bit of mis-history, he said, “Pyman met Brigadier Poett and Colonel Pine-Coffin, and it was Pyman that made the statement about being two minutes late…The statement is clearly documented in the No. 6 Commando War Diary, and I have spoken to members of the Troop who were actually there, who confirmed it. The Commando veterans have always known that Lovat was not the first to get there, and not the first across the bridge.”

Millin said, “We got to Bénouville. I had to stop again because we were under fire there and we couldn’t get down the main street. We were taking shelter behind the low wall to the right of the entrance to the village, and [Lieutenant]Colonel [Derek] Mills-Roberts of No. 6 Commando [part of Lord Lovat’s 1st Special Service Brigade]––he was across the road looking round his side of the wall––came dashing across to me and said, ‘Right, Piper, play us down the main street.’ He wanted me to run. I said, ‘No, I won’t be running. I will just play them as usual.’ So I piped them in, and they all followed behind me and through the village.”

At about this time, with snipers still active, a Corporal Killean, a 7th Battalion PIAT gunner, received permission from Pine-Coffin to take a shot at the Bénouville church steeple, from which sniper fire had been coming. A single missile blew away 12 snipers who had been in there.

Millen was piping Blue Bonnets Over The Border. He said, “Then I continued along the road and there was a lot of white dust with the noise and the explosions and everything. So at the end of the village, I stopped there and then Lovat came up to me and he said, ‘Well, we are almost at the bridges. About another half a mile. So start your pipes here and continue along this road and then swing round to your left. Then it’s a straight road down to the bridges.’ “

Millin started piping again and continued along the road, his eyes looking nervously for any sign of snipers. “I had begun to become conscious of snipers by this time… Turned round left and then I could see the bridges about 200 yards down the road and a pall of black smoke over the bridges and the sound of mortars bursting. So I kept piping down the road.”

Millen said, “Lovat passed and this Airborne officer approached us and Lovat and the officer shook hands and started to discuss the situation. Then Lovat came to me and said, ‘Right, piper, we’re crossing over.’

“So I start walking, put the pipes up. We can hear the shrapnel, whatever it was, hitting the metal sides of the bridge. Well, when we got almost to the other side, I started up the pipes. Coming off the bridge, I stopped again because Lovat put his hand up—the indication was to stop. Lovat said, ‘Another 200 yards along this road, piper, there is another bridge but we won’t have the protection that we have here because it’s not a metal-sided bridge, it’s railings,’ as he called them, ‘and when you get there, no matter what the situation, just continue over. Don’t stop.’

“So I struck up the pipes and marched merrily along the road, and he was walking behind me and others strung out behind. I was still playing Blue Bonnets Over The Border and we came to the [Ranville] bridge. I could see across the bridge, and there were two Airborne chaps dug in on the other side and they were frantically pointing out to the sides of the river that it was under fire, sniper fire, and whatever. So I then looked round at Lovat and he indicated to me by his hand, carry on across.

So I kept piping, but it was the longest bridge I ever piped across! I got safely over and shook hands with the two Airborne chaps in the slit trench.” As Lovat and Piper Millin continued on to the east, the unit came under mortar fire.

“We all jumped into a ditch,” Millin said, “and we could hear the shrapnel coming through the hedge, and this is the spot where the pipes were injured. Not seriously, though; they could still be played.”

With 7th Para now at the bridges in force and the situation seemingly under control, Lovat and his Commandos marched off to the northeast to see if they could be of assistance at the Merville battery, not knowing if the British troops that had attacked it early that morning had succeeded in neutralizing it. (They had.)

Except for sporadic sniper fire and occasional mortar rounds, the British troops at the two Orne bridges spent the rest of D-Day without being seriously harassed. As evening fell, the 2nd Royal Warwickshires that had waded in at Sword Beach reached the bridges. Howard briefed their commander and handed over control of the bridges to them, then marched D Company off to Ranville to rejoin the rest of the 2nd Ox and Bucks that were now there; Pine-Coffin’s 7th Battalion would follow.

Pine-Coffin noted, “Thus ended the first day of action for the Battalion. It had been a particularly full day and had cost much blood and sweat, but the objective had been achieved and it was a comforting thought to reflect that, during the whole 23 hours of operation, not a single German other than prisoners had set foot on the bridge. With the arrival of the seaborne forces, the west side of the Divisional bridgehead was secured firmly and the whole Battalion was freed to face the other way and re-join the rest of the Division.”

And even though D Company had not yet made the newspapers, Howard and his men were justifiably very proud of what they had accomplished. Their coup de main operation had come off in textbook fashion with minimal casualties to their own forces. They just hoped that the rest of the invasion had gone so well.

This article is adapted from Flint Whitlock’s book, If Chaos Reigns: The Near-Disaster and Ultimate Triumph of Allied Airborne Forces on D-Day. (Casemate, 2011)