By Frank Johnson

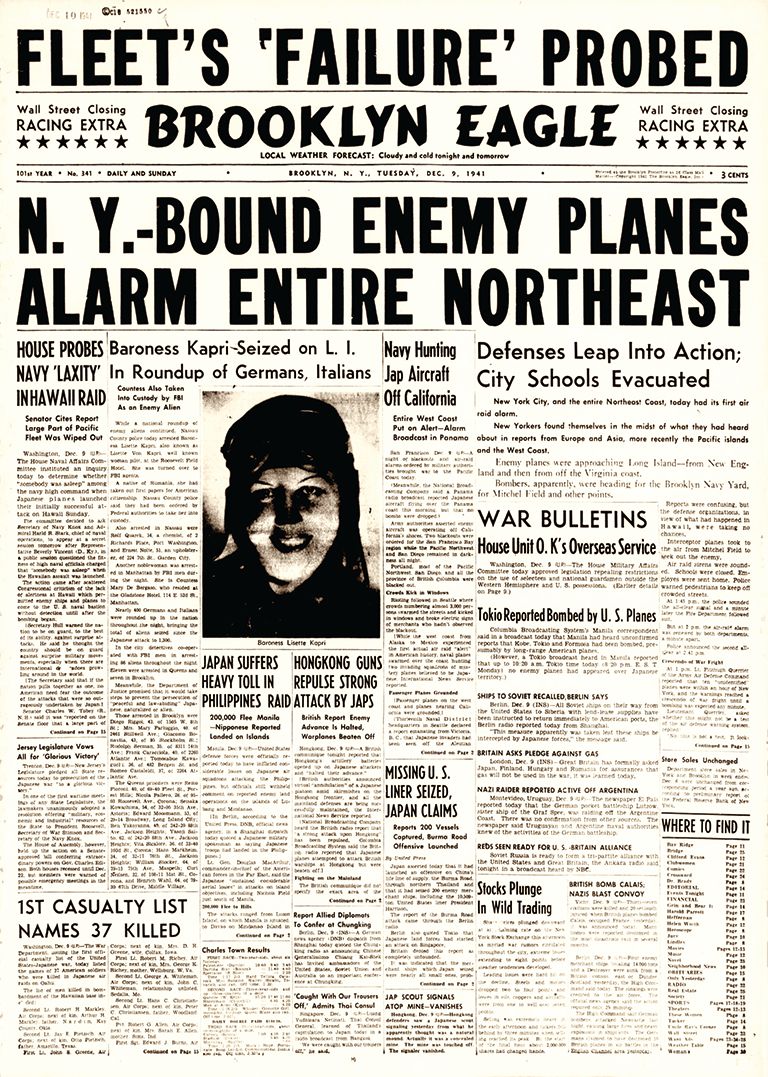

Shortly after noon on Tuesday, December 9, 1941, in the wake of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, hostile warplanes were reported 200 miles off the Virginia coast and heading for New York City.

The entire U.S. East Coast went on alert. At 1:30 p.m., New York heard its first-ever air-raid warning as a fire truck sped through the streets with siren wailing. More baffled than alarmed, shoppers and strollers stared skyward, office workers crowded windows, and children streamed out of dismissed schools. Police precincts went on emergency standby.

The first report of the sighting had been sent to Mitchel Field on Long Island, home base of the First Air Force led by Major General Herbert A. Dargue. Within minutes, interceptor fighters took off and ground crews hastily manned antiaircraft guns. An “all clear” siren sounded in the city at 1:45 p.m., followed by another warning at 2:04 p.m. The second “all clear” did not come until 2:41 p.m.

In the city streets, the alarms did not affect vehicular traffic, but small groups of people gathered around newsstands, staring at headlines. “Air raid alarms are sounded here,” shrilled The Sun, one of the city’s nine daily newspapers. Many New Yorkers cracked wise, unable to believe an air attack on their city was imminent. The sky remained clear except for clouds, no planes appeared, and there was confusion along the East Coast.

General Dargue said he did not think that the warnings constituted a rehearsal. “We can’t explore the mechanics of our alarm system,” he told reporters. “Remember the number of alarms over London without any bombs being dropped. I will not disclose the source of this alarm.” The Brooklyn-born Dargue, a 1911 West Point graduate, Coast Artillery veteran, and holder of the Distinguished Flying Cross, was killed three days later in the crash of an Army Air Forces plane near Bishop, California.

In Boston, Massachusetts, which was alerted for more than an hour on the afternoon of December 9, State Public Safety Director J.W. Farley stated eventually, “The Army and Navy now inform us that this was a dress rehearsal. All phases of the test were met satisfactorily.”

Similar alarms shook residents on the West Coast. At 11:59 a.m. that day, the San Francisco police broadcast a warning that “planes had been sighted approaching from sea,” and the Oakland police issued a similar alert at noon. An “all clear” signal was flashed nine minutes later. The Fourth Army Interceptor Command reported that “30-odd enemy planes ranged last night from San Jose at the south tip of the bay to the huge naval yard at Mare Island.” It triggered the first blackout in San Francisco history.

The command said that USAAF pursuit planes followed the first of the enemy squadrons, but were unable to locate them. Navy units then launched a fruitless search for an aircraft carrier possibly 500 miles off the coast. Lt. Gen. John L. DeWitt, leader of the Fourth Army and the Western Defense Command, said, “I don’t think there’s any doubt that the planes came from a carrier…Why bombs were not dropped, I do not know. It might have been better if some bombs had dropped to awaken this city.” He warned, “This is war. Death and destruction may come from the skies at any moment.”

In the hours following the Pearl Harbor disaster, fears of a possible Japanese invasion on the West Coast were real, with widespread confusion and panic. There were only 100,000 troops to guard the entire Pacific shore and little ammunition. A frantic official called the White House and suggested that, because the Pacific coast was so vulnerable, new defense lines would have to be drawn up in the Rocky Mountains. Major General Joseph W. Stilwell, wrote in his diary, “If the Japs had only known, they could have landed anywhere on the coast, and after our handful of ammunition was gone, they could have shot us like pigs in a pen.”

A Newsweek reporter wrote from San Francisco that, “First air raid alarm caught the city unprepared and uninstructed. The only sirens were on the Ferry Building and two small bridges. Police and Fire Department vehicles, racing through the streets as auxiliary sirens, increased the confusion. Neon signs, operating on a time-lock device, could not be doused.” Irritated by incessant sirens, one San Franciscan asked, “If there are Jap planes around, why aren’t they dropping bombs?”

The jitters had started in San Francisco on the night of December 7. City officials ordered the Golden Gate Bridge blacked out, but lights were on at the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge. A driver was shot and critically injured by a civilian sentry when she refused to halt and dim her headlights. Army intelligence officers reported Japanese planes over San Francisco Bay, but they turned out to be American. Someone mistook the red circle at the center of the USAAF insignia for the rising sun of Japan.

In Los Angeles, home to an estimated 50,000 Japanese-Americans, Sheriff Eugene Biscaliuz mobilized the 10,000-man Civilian Defense Committee while FBI agents and troops from Fort MacArthur herded “key” Nisei citizens into a wire enclosure on the Sixth Street pier. An antiaircraft battery defending the city opened up on imaginary warplanes, and the shell fragments injured dozens of unsuspecting residents.

In San Diego, naval authorities stationed guards to prevent any Nisei from fleeing to Mexico, and antiaircraft batteries were set up at vital communications and power stations along the California coast. Machine-gun emplacements were dug on California beaches, and Coast Guard motor lifeboats escorted San Francisco crab fishermen. Uncoordinated defense measures along the Pacific coast were offset by outbursts of hysteria. In Seattle, a mob of 2,000 angry citizens attempted to enforce the blackout by smashing windows and looting lighted stores.

The first efforts at civil defense in the nation’s history were inept and chaotic on both coasts. Few cities had air-raid sirens. San Francisco had only five low-range sirens for signaling drawbridge openings and special events, Los Angeles used a combination of police and fire sirens, and New York used the “super whistle” at Consolidated Edison’s East River generating plant. In Boston, merchants urged the mayor to shun practice alarms until after the busy Christmas season.

Invasion fears mounted across the country as guns sprouted on city rooftops and along the seashores. Searchlights probed the night skies as air-raid wardens patrolled the streets, and families tacked up black cloth on their windows. No one felt safe. Even in Wyoming, nervous citizens called for the construction of bomb shelters while others eyed caves and mine shafts for refuge in case of attack.

New York’s colorful Mayor Fiorello La Guardia warned, “The war will come right to our cities and residential districts. Never underestimate the strength, the cruelty of the enemy.” As he spoke, German U-boats off the East Coast prepared for a five-month onslaught against Allied merchant shipping.

The Pearl Harbor attack had silenced the isolationists and shocked Americans into realizing that World War II was now much more than just a matter of headlines and radio broadcasts. Though thousands of miles away from the action, millions feared an invasion at any moment.

The American Legion commander in Wisconsin called for a guerrilla army composed of the state’s 25,000 licensed deer hunters. The Georgia State Guard, a militia of men too old or young for the draft, started erecting coastal defenses, while Peach State convicts were conscripted to strengthen seashore approaches and build bridges for carrying military transport. A coat of dull-gray paint was daubed over the distinctive gold-leaf dome of the Massachusetts State House on Boston’s Beacon Hill to make it less conspicuous from the air, black paint was slapped on the gold-leaf roof of the Federal Building in Manhattan, and, as part of an Army experiment, a dense smoke screen was released to conceal the steel mills of Gary, Indiana.

The colonial spirit of 1775 was echoed in the central Massachusetts town of Athol, where latter-day minutemen drilled with shotguns and squirrel rifles, while farmers on Whidbey Island in Puget Sound, Washington, took up pitchforks, shotguns, and clubs to patrol the beaches.

In the nation’s capital, an antiaircraft gun crew set up on the roof of the Commerce Building, across from the Washington Monument, and machine-gun emplacements were installed on the roof of the White House and near the Lincoln Memorial. Around the executive mansion and other key federal buildings, policemen, soldiers bearing aging Springfield .30-caliber rifles, and Marines with fixed bayonets stood guard. Every entrance to the U.S. Capitol was guarded, and the credentials of congressmen and journalists were checked rigorously.

Roosevelt rejected an Army proposal to paint the executive mansion black but agreed to have blackout curtains measured for its 60 rooms and 20 bathrooms. The lamps on the grounds were extinguished, FDR’s Secret Service contingent was quadrupled, and in the White House basement, Army engineers marked off the entry for a tunnel leading to a temporary air-raid shelter in the old vaults of the Treasury Building. But Roosevelt balked at the idea of holing up there and told Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr. with a grin that he would use the shelter only if he could play poker with the nation’s gold hoard.

In case of an attack on the White House, contingency plans were drawn up for men of the crack 3rd Infantry (“Old Guard”) Regiment to be rushed in from nearby Fort Myer, Virginia, and for Army engineers to stand by with bulldozers and other heavy equipment. At an air strip on the edge of Washington, a bomber was ready to whisk the president away if necessary. FDR, who was about to host British Prime Minister Winston Churchill for three weeks during the Christmas season, was issued a gas mask, which he slung over his wheelchair.

Though stunned and angered by the Japanese attacks on Pearl Harbor, Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines, the president kept his jaunty demeanor while fear swept the country. After dining with him and briefing him on the situation in bomb-ravaged London, famed CBS radio correspondent Edward R. Murrow reported, “I have seen certain statesmen of the world in time of crisis. Never have I seen one so calm and steady.”

In cities and towns across the country, department and hardware stores quickly sold their stocks of black paint and cloth, lanterns, portable radios, flashlights, candles, shovels, first-aid kits, whistles, hatchets, oil stoves, and thermos flasks. Sleeping bags disappeared from the stores almost immediately. A New York housewife ordering 22 mattresses explained, “If we’re going to have to sleep in the subway, at least we’ll be comfortable.” She was unaware that Mayor La Guardia had officially ruled out the city’s subways as safe air-raid shelters, although thousands of Londoners were finding refuge underground every night.

The alarms and confusion, meanwhile, continued. A blackout interval in Los Angeles caused five times the usual traffic injuries, while an alarm in Seattle on December 23 prompted a modern Paul Revere to clamber on a horse and gallop through the streets shouting, “Blackout! Air raid! The Jap bombers are coming!” Naval stations around Chicago were placed on alert on Christmas Day when someone reported “strange planes” over Lake Michigan. But no one informed police, civil defense, or Army officials. During a false air-raid alarm in New York City, school officials disregarded civil defense advice and released a million children from their classrooms. They played in the streets, shouting, “Air raid, air raid!” while frantic parents searched for them.

Christmas Eve, 1941, arrived, and Americans strove to put aside their fears and celebrate in traditional ways. Thirty thousand shivering people were admitted to the White House grounds to watch Roosevelt light the national tree and listen as Churchill tried to lift their spirits. “Let the children have their night of fun and laughter,” he declared. “Let the gifts of Father Christmas delight their play. Let us grownups share to the full in their unstinted pleasures before we turn again to the stern task and the formidable years that lie before us, resolved that, by our sacrifice and daring, these same children shall not be robbed of their inheritance or denied their right to live in a free and decent world.”

New Year’s Eve brought another respite—albeit briefly—for troubled Americans. According to veteran observers of New York society, the celebration in Times Square was one of the most uninhibited on record as some 500,000 revelers blew horns, rang bells, while Broadway’s neon lights blazed. In the city’s Father Duffy Square, a large crowd joined in as Lucy Monroe sang “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

But 1942 found America woefully unready for war and facing its sternest six months ever as U-boats marauded unmolested on the Atlantic coast and Japanese forces rampaged in the Far East. Invasion fears persisted.

When a reporter asked Roosevelt in February if the country was open to attack, he said, “Enemy ships could swoop in and shell New York, enemy planes could drop bombs on war plants in Detroit, enemy troops could attack Alaska.” The reporter persisted, “But aren’t the Army and Navy and the Air Force strong enough to deal with anything like that?” FDR answered, “Certainly not.” His pessimism was confirmed a week later.

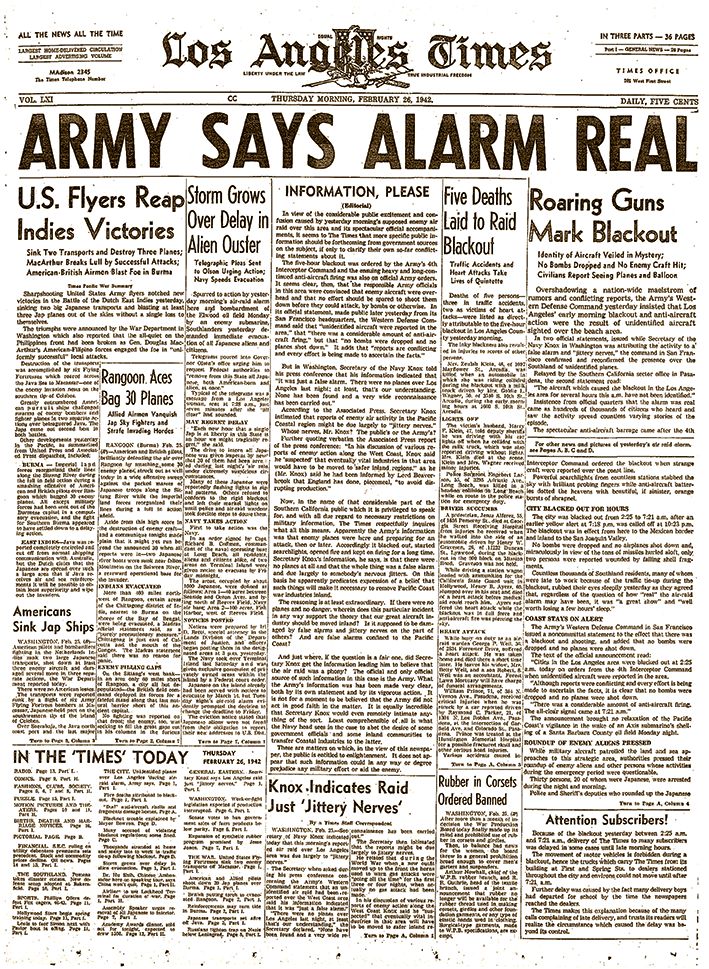

On the evening of February 23, while Roosevelt was delivering one of his radio “fireside chats” to the nation, the Japanese submarine I-17 surfaced a mile off Santa Barbara, California, and lobbed 25 shells in 20 minutes at an oil refinery. It was the first direct enemy attack on the continental U.S. The damage was minor, but West Coast nerves were shaken. Two nights later, “Japanese bombers” were reported over Los Angeles, and the city panicked. Although there were no planes, antiaircraft guns opened up. Shells falling back to earth damaged two houses, and two people died in traffic accidents on the darkened streets.

Many fearful, frustrated citizens turned their anger on the 900,000 Americans of German, Italian, and Japanese descent, seeing potential spies and saboteurs. Soon after war was declared, an estimated 5,000 German-Americans and Italian-Americans were rounded up by the FBI and interned.

Roosevelt told Attorney General Francis Biddle, “I don’t care so much about the Italians. They are a lot of opera singers, but the Germans are different. They may be dangerous.” On February 19, FDR signed an executive order authorizing Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson to bar German, Italian, and Japanese aliens from certain “military areas” in the U.S. Broad in tone, it was aimed at Japanese-American citizens.

The FBI rounded up suspected German spies in the New York area, but German-Americans were spared the mob attacks and hysteria that beset their parents during World War I. The 1941-42 hatred was directed mainly at Japanese-Americans, the majority of whom were law-abiding and well educated, as demonstrated in Hawaii just after the December 7 attack. Two thousand Nisei serving there in the U.S. Army helped to protect island installations, aided by Japanese civilians and members of the Hawaii Territorial Guard. The Honolulu Star Bulletin dismissed reports of Japanese subversion in the islands as “weird, amazing, and damaging untruths.” Later nearly 10,000 men answered when the Army called later for 1,500 Nisei volunteers.

Yet, Japanese business and fraternal organizations were assumed to be subversive, fishermen in Hawaii and on the West Coast were accused of equipping their boats with powerful radios for transmitting to Japan. Store windows were smashed and doors daubed with hostile slogans. Nisei merchants hung “I am an American” signs in their windows, but banks refused to cash their checks, insurance companies canceled their policies, and traders stopped deliveries. Along the Tidal Basin in Washington, D.C., zealots felled four cherry trees which had been presented to America by the people of Tokyo in 1912, the S.S. Kresge chain removed all Japanese merchandise from its five-and-ten stores, a Buddhist temple in Los Angeles was ransacked, and Tin Pan Alley loosed a flood of anti-Japanese songs.

When a Japanese-American bar owner and his wife were attacked by a mob on skid row in Los Angeles, folk singer Woody Guthrie and a few sailors interceded. Strumming his guitar, Guthrie sang an old union song: “We will fight together, we shall not be moved.” Singing passersby linked arms and the mob melted away.

Acts of sabotage preceding a Japanese invasion were expected on the West Coast, but none were reported. This proved nothing, fumed California Attorney General Earl Warren. The Japanese-Americans were just holding back, he suggested, “until the zero hour arrives.” General DeWitt declared, “A Jap’s a Jap. It makes no difference whether he’s an American or not…I have no confidence in their loyalty whatsoever.” Led by such strident voices as columnist Walter Lippmann, a growing chorus demanded swift action against Americans of enemy-alien descent.

Life magazine spread alarm with its March 2, 1942, issue. Behind a cheery cover photograph of actress Ginger Rogers smiling broadly while fishing in a western creek, the editors warned, “Now the U.S. must fight for its life.” With illustrations, the magazine painted a grim portrait of San Francisco and the Bay Bridge burning, war plants and New York’s La Guardia Airport being bombed by German planes, and Japanese troops dragging chained Americans through the snow after an invasion of Alaska.

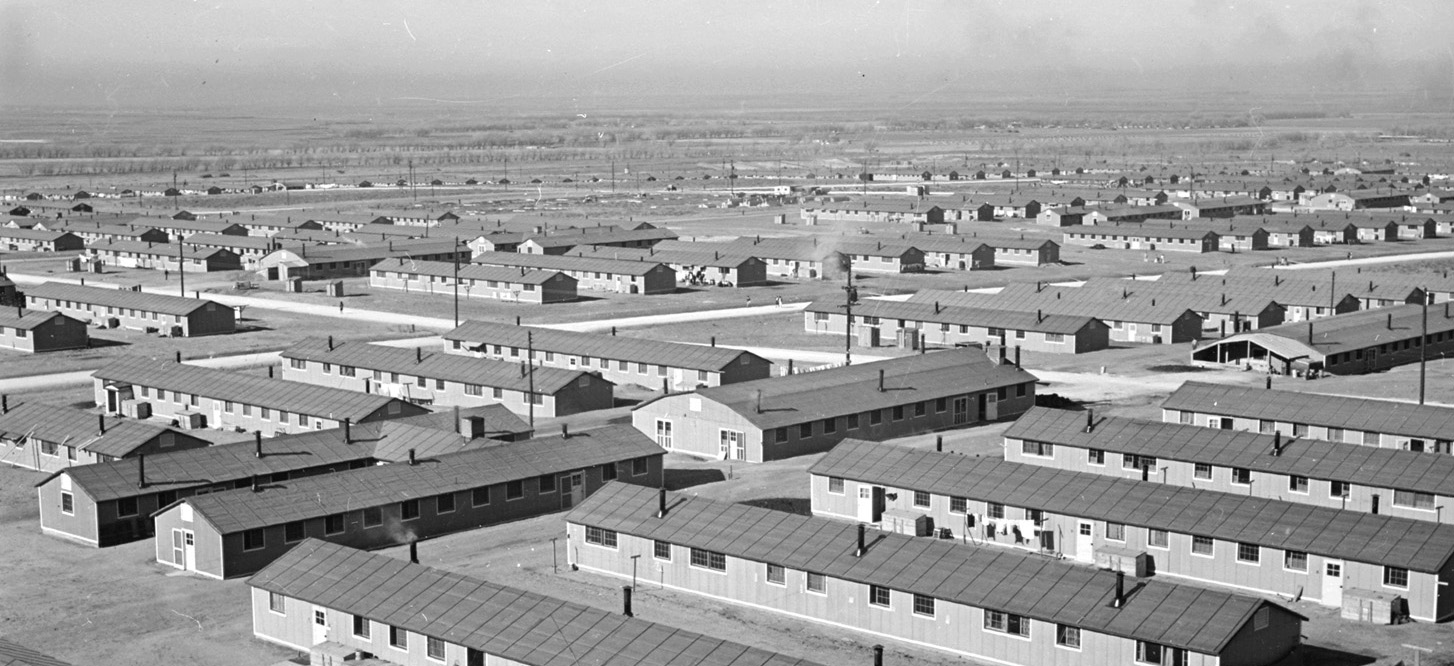

The outlook worsened for the Japanese-Americans. The Roosevelt administration created the War Relocation Authority as part of the Office of Emergency Management on March 18. It was headed by Milton Eisenhower, the youngest brother of then-Major General Dwight D. Eisenhower, and its objective was to “take all people of Japanese descent into custody, surround them with troops, prevent them from buying land, and return them to their homes at the close of the war.” Late that month on the West Coast, General DeWitt’s troops began rounding up 114,490 Japanese-American men, women and children—including 75,000 U.S. citizens.

Although no charges of espionage or sabotage were ever brought against the Japanese-Americans in the United States or Hawaii, their treatment went unquestioned.

Many Japanese-Americans were given only 48 hours in which to uproot their lives and dispose of homes, stores, farms, and cars. Predatory bargain-hunters snapped up their belongings for a fraction of the true value. Then families, name-tagged and hauling suitcases and bedrolls, were led off by armed soldiers in trains or trucks to assembly centers, such as hastily converted fairgrounds and the Santa Anita racetrack.

The Nisei families went without protest and were generally stoical about their fate. Eventually, during the spring and summer of 1942, they were shipped to 10 inland “relocation centers” scattered from the California desert to remote areas in Utah, Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Wyoming, and Arkansas.

Penned in compounds ringed by barbed-wire fences and armed troops, the displaced Japanese-Americans lived in drafty wood-and-tarpaper barracks, with a 20-by-25-foot “apartment” allocated to each family. They slept on Army cots, ate in mess halls, shared communal washrooms, and no one was allowed to have a razor, scissors, radios, or pets. The children attended WRA-run schools, where essay assignments asked ironically, “Why are you proud to be an American?”

Most internees spent at least three years in the camps. The only way to leave was to join the armed forces. More than 17,000 young Nisei men—many of them the brothers and sons of incarcerated families—fought in World War II. Trained at Camp Shelby, Mississippi, the soldiers of the U.S. Army’s 442nd Regimental Combat Team distinguished themselves in the Italian campaign and from the Vosges Mountains to Champagne in France. The most decorated Army unit in American history, “Go for Broke” suffered 30 percent casualties, earned eight Presidential Unit Citations, a Medal of Honor, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 560 Silver Stars, and 3,600 Purple Hearts.

The first months of 1942, meanwhile, brought a severe test of American fiber as Allied bastions fell in the Far East, British and U.S. troops retreated in Malaya and the Philippines, and German U-boats sank thousands of tons of merchant shipping within sight of the East Coast. But the urge to fight back against fascism soon took hold, and invasion fears and hysteria dissipated.

Six months after Pearl Harbor, the tide began to turn. Col. James H. Doolittle’s daring B-25 bomber raid on Tokyo in April ignited American spirits, and the battles of Coral Sea and Midway in May and June blunted Japanese naval aggression. Then the Allies went on the offensive—in the skies over Nazi-occupied Europe, on the Eastern Front, and at Guadalcanal, El Alamein, and North Africa. By the end of the crucial year which had started so badly, Allied forces were rolling along the hard road that led to the eventual defeat of the Axis Powers.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments