By Mike Phifer

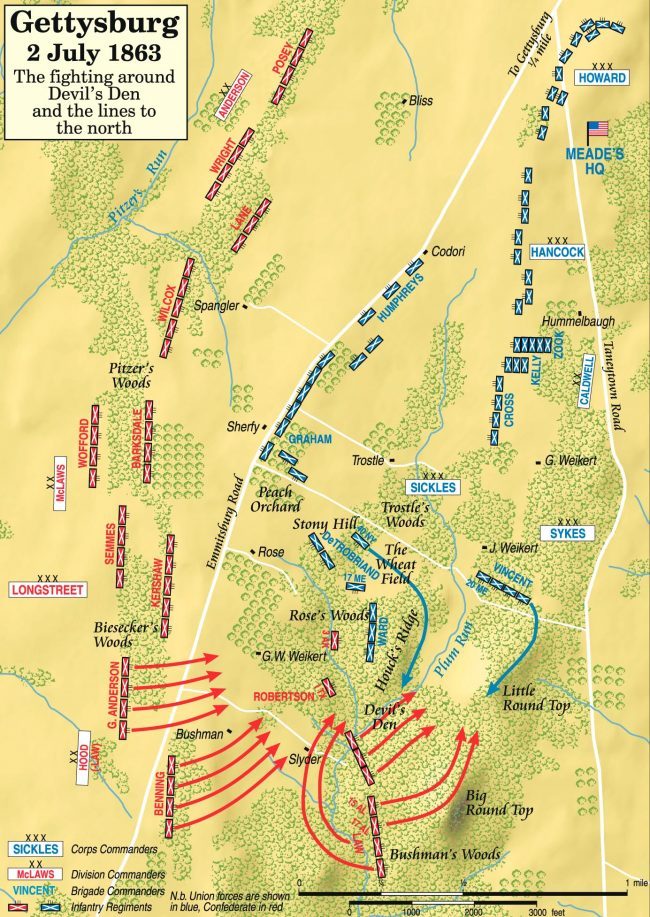

On July 2, the day of the Battle of Gettysburg’s Peach Orchard conflict, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George Meade had inspected the ground on his army’s left flank at dawn, and ordered Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles to hold the southernmost end of Cemetery Ridge with his III Corps. Yet ridge was a misnomer for the ground that Meade ordered Sickles to defend. In some places it was not a ridge at all. Indeed, its southern end was commanded by Little Round Top to the south and even by a low ridge due west on the near side of Emmitsburg Road.

Sickles fumed over the injustice of Meade’s decision. At 11 am he rode to Meade’s headquarters and complained about his poor position. Meade stifled the anger he felt at Sickles’ objections and reiterated his orders. Sickles was bound and determined, though, to have his way. He believed that Meade’s orders put his troops in peril. He also believed they would be crushed in the near-certain Confederate attack against that sector of the field.

For that reason, Sickles advanced his two divisions 1,500 yards west of the line on Cemetery Ridge that he had been instructed to hold. The new position his troops occupied was a low ridge where farmer Joseph Sherfy’s Peach Orchard was located. Events would prove that Sickles was right about the Confederate attack but wrong regarding the best position to receive such an attack. His understrength corps, comprised of just two divisions, did not have enough troops to adequately defend his new position. Sickles, a headstrong politician who lacked West Point training, deployed his troops in a sharp angle, known as a salient, which was difficult to defend in the face of a determined attack.

600 Yards Swarming with Yankees: a Failure of Confederate Reconnaissance

Arriving at the edge of the woods on Seminary Ridge on the west side of Emmitsburg Road at mid-afternoon that day, Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws was astonished at what he saw. The Georgia-born general saw just 600 yards of ground swarming with Yankees. He had been told by his scouts that there were no large bodies of Union troops in the area. Indeed, a Confederate reconnaissance at dawn had revealed that only one regiment of Union infantry and one battery was positioned on Emmitsburg Road in front of McLaws’ path of attack.

Both Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s division on the extreme Confederate right and McLaws’ division to his left awaited orders to attack in the late afternoon from First Corps commander Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. Confederate Army of North Virginia commander General Robert E. Lee had ordered Longstreet to roll up the Union left flank using his two divisions on hand.

Lee had even gone so far as to inform McLaws that he should place his troops perpendicular to the Emmitsburg Road and to attack north along its axis. Lee’s orders were that McLaws was to attack first followed by Hood. Based on what he saw to his front, McLaws believed Sickles’ new position threatened to derail his attack.

Twice a staff officer dispatched by Longstreet arrived to ask McLaws why he had not begun his attack. McLaws said that he needed to destroy the enemy’s batteries with his own artillery before sending his infantry forward. When he received a third order stating that he was to attack immediately, McLaws told the aide-de-camp that he would attack within five minutes.

Before the five minutes had elapsed, though, McLaws received orders from Longstreet that Hood would attack first. The change in plans was both a blessing and a curse. It gave McLaws more time to plan how he would attack the Union III Corps, but it also robbed him of the element of surprise. Once Hood advanced, the Yankees would know that other Confederates on Seminary Ridge were likely to attack as well.

Precursor to Gettysburg: Lee Reorganizes the Army of Northern Virginia

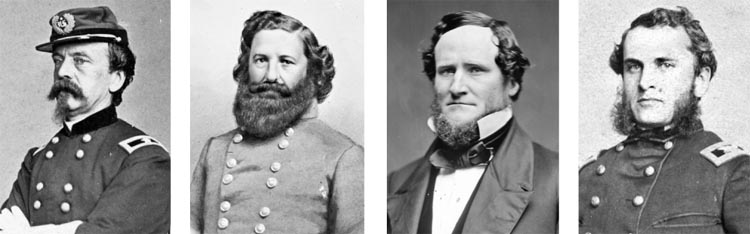

After the Confederate victory at Chancellorsville, Lee decided to invade the North a second time. In the wake of the death of Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson on May 10, Lee reorganized the Army of Northern Virginia. Longstreet retained the I Corps. Lieutenant generals Richard Ewell and A.P. Hill would command, respectively, the newly created II and III Corps.

The Confederates crossed the Potomac on June 15 and headed for Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. But on June 28 Lee ordered his dispersed army to concentrate at Gettysburg to deal with the threat posed by Maj. Gen. George Meade’s Army of the Potomac whose lead elements had reached Frederick, Maryland.

Finding the Federals in possession of Gettysburg, the Confederates attacked with their II and III Corps on July 1. The day went well for the Confederates, but the Union Army withdrew to strong positions atop Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill just below the town. Arriving late in the day, Meade noted that Cemetery Ridge and the two Round Tops east of Emmitsburg Road also would make fine defensive positions. He therefore decided to stay and fight at Gettysburg.

In his meeting with Lee on the night of July 1, Longstreet said he was against an assault against Union forces on Cemetery Ridge; instead, he favored seeking a better ground to fight in another location. Lee disagreed. “If the enemy is there tomorrow, we must attack him,” said Lee.

By 12 pm on July 2 the majority of the Army of the Potomac had arrived. Meade’s forces were arrayed in a fishhook-shaped position. The Union defense began at the two Round Tops and ran north along Cemetery Ridge to the edge of town. From the town it curved east toward Culp’s Hill to form the hook. Meade would benefit from interior lines. This meant he required fewer troops to man his line than Lee and could shift troops faster than Lee.

Anchoring Culp’s Hill was Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum’s XII Corps. Adjacent to it to the west was the I Corps. Following the death of Maj. Gen. John Reynolds on July 1 in Herbst Woods, command of the corps had devolved to Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday. Holding Cemetery Hill was Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard’s XI Corps. The northern end of Cemetery Ridge was held by Maj. Gen. Winfield Hancock’s II Corps, and the southern end by Sickles’ III Corps. Maj. Gen. George Sykes’ V Corps formed the Union Army’s reserve. Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s VI Corps was en route to Gettysburg. It was expected to arrive late on July 2.

While the Union corps commanders organized their respective positions on the morning of July 2, Lee dispatched several scouting parties. Lee directed Captain Samuel Johnston, an engineer on his staff, and Major John Clarke, an engineer on Longstreet’s staff, to reconnoiter the Union left.

While awaiting the scouting parties’ return, Lee met again with Longstreet near the Lutheran Seminary Building on Seminary Ridge shortly after sunrise on July 2. The I Corps consisted of three divisions: Maj. Gen. John Hood’s division, Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ division, and Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division. Pickett’s division was not on hand and did not arrive until the night of July 2.

Joseph Sherfy’s Peach Orchard

While they were discussing the plan of attack for the day, Hood joined the conference. “The enemy is here, and if we do not whip him, he will whip us,” said Lee, pointing at a map. Longstreet was reluctant to attack without all three of his divisions present. “I never like to go into battle with one boot off,” Longstreet said to Hood. To compensate for this, Lee ordered Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s division of the III Corps to go into action on McLaws’ left.

Johnston returned in mid-morning to find Lee, Longstreet, and Hill sitting on a log. Johnston told Lee that he had scouted south along the west side of Seminary Ridge where he had reconnoitered Sherfy’s Peach Orchard. He also had scouted Little Round Top. He told Lee that there were no large Union formations in that area. This gave Lee the impression that the Federal left was exposed and that Longstreet would be able to roll up the Union left flank. Unfortunately, Johnston’s report was grossly inaccurate.

McLaws arrived to meet with Lee. The Confederate commander pointed on a map to a location along Emmitsburg Road near the Peach Orchard. “I wish you to place your division across this road, and I wish you to get there if possible without being seen by the enemy,” Lee told the Georgian.

Once McLaws and Hood had placed their divisions in position southwest of Cemetery Hill, they were to attack north along the Emmitsburg Road, driving the enemy before them. As their attack progressed, they were to clear the Federals from Cemetery Ridge and, if possible, from Cemetery Hill. Anderson’s corps was to help clear the Federals from Cemetery Ridge. To pin down the forces on the Federal right wing, Lee ordered Ewell to launch a diversionary attack against Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill.

Longstreet did not want to get underway until Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s brigade of Hood’s division arrived after a 24-mile march. Shortly after noon 14,500 Confederate troops set off from Herr’s Ridge on their approach march. McLaws’ division led the column with Hood’s division following behind. The column stretched for three miles.

Brigadier General Joseph Kershaw’s Palmetto State brigade led the advance. The brigade had just passed Black Horse Tavern on the Fairfield Road when Kershaw received an order from McLaws to halt. The problem was that if the column crossed the crest of a hill that lay ahead it would be visible to the prying eyes of Yankees manning a Union signal station atop Little Round Top.

McLaws and Johnston set out at once to find a route by which the column could avoid being detected. Longstreet soon rode up from the rear of the column to see what had caused the delay. McLaws showed Longstreet how the column could be seen from the crest of the hill. “Why this won’t do,” said Longstreet. “Is there no way to avoid it?” McLaws said there was a way to avoid the hill, but it would require countermarching. Longstreet gave his approval. The column marched all the way back to Herr’s Ridge, followed Fairfield Road toward Gettysburg for a short distance, and then turned south on a country road leading to Pitzer’s Schoolhouse just west of Seminary Ridge. The foot soldiers quickened their pace to make up for lost time.

Sickles and Hunt Discuss Moving 10,600 Troops Forward to the Peach Orchard

After the terse rebuke he received from Meade, Sickles returned in the late morning to his corps. He was accompanied by Brig. Gen. Henry Hunt, the Army of the Potomac’s chief of artillery, who Meade had dispatched to assist Sickles in placing his field artillery. Sickles showed Hunt the Peach Orchard where he wanted to deploy his corps. Sickles could not bear to let the Confederates occupy the position. Sickles showed Hunt how the high ground where the Peach Orchard was situated offered enemy artillery a commanding advantage over his guns. As a professional soldier, Hunt knew that the position Sickles proposed was impracticable.

As Hunt prepared to return to Cemetery Hill, Sickles asked him if he had his permission to move his 10,600 troops forward to the Peach Orchard. Hunt said that he had no authority to authorize such a move. Before riding off, Hunt suggested that Sickles send a reconnaissance party to scout Pitzer’s Woods on Seminary Ridge west of Emmitsburg Road to determine whether the Confederates held the wooded tract in force.

Sickles dispatched four companies of the First U.S. Sharpshooter Regiment led by Colonel Hiram Berdan and a detachment of the Third Maine Infantry led by Captain Joseph Briscoe at noon to probe the woods. The force was composed of 100 sharpshooters and 210 regular infantry. Berdan and Briscoe, both of whom were mounted, ordered their troops into skirmish lines and proceeded west over ground strewn with rocks and branches.

The Yankees moved into Pitzer’s Woods just as two regiments belonging to Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s Alabama brigade of Anderson’s division were about to occupy them. Wilcox had sent Colonel William Forney’s 10th Alabama and Colonel John Sanders’ 11th Alabama Regiments of his brigade forward to feel for the enemy.

The Yankees fired into the 11th Alabama’s right flank. The unexpected enemy fire disrupted the 11th Alabama, and it fell back on its supporting line. Having had the advantage of seeing what had occurred without suffering any casualties, the 10th Alabama rushed forward and delivered several crashing volleys at the Federal troops that had unwisely passed through the woods into an open field. The Yankees rushed back to the woods. The two sides exchanged fire for 20 minutes at which time Forney ordered his men to charge. This time it was the Federals who fled back to their supporting line.

The reconnaissance party reported to Sickles that there were numerous Confederates in Pitzer’s Woods. Sickles already had made up his mind to occupy the Peach Orchard despite Meade’s rebuke. With flags fluttering in the wind and bayonets gleaming in the sun, the III Corps advanced to the Peach Orchard at 2 pm Sickles made no effort to inform Meade of his advance.

Observing the III Corps move forward from its position on Cemetery Ridge, Hancock was aghast. “What in hell can that man Sickles be doing!” he exclaimed to Second Division commander Brig. Gen. John Gibbon.

Sickles deployed Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphrey’s Second Division along Emmitsburg Road. This deployment left a critical 500-yard gap between Humphrey’s men and the left flank of Hancock’s II Corps on Cemetery Ridge. Sickles directed Maj. Gen. David Birney to place his First Division in the Peach Orchard in such a way that it angled southeast along a 24-acre Wheatfield to Houck’s Ridge.

Meade to Sykes: “Hold the Position At All Costs”

Longstreet’s two divisions reached Seminary Ridge at 3 PM, but it would be another hour before they were ready to attack. As the first of his troops crested the ridge, Union artillery opened fire. McLaws ordered Kershaw to deploy his South Carolina troops for battle. The burly division commander then rode off to hurry forward his rear brigades. As he did so, he ordered Colonel Henry Cabell, who commanded the division’s artillery, to rush his guns forward to respond to the Union batteries already in action. Cabell’s guns were the first of many that would be deployed against Sickles’ III Corps salient. Confederate Colonel Edward Porter Alexander, Longstreet’s artillery chief, posted four batteries from the First Corps’ Artillery Reserve to supplement four of McLaws’ batteries. Altogether, McLaws had 36 pieces in position to pound the Peach Orchard.

While Longstreet’s two divisions were getting into place for their attack, Meade was meeting with his corps commanders at his headquarters located in a farmhouse on the reverse slope of Cemetery Ridge. During the course of the meeting Meade learned that Sickles was not in position on Cemetery Ridge. When Sickles arrived to join the meeting, an irate Meade told him to return immediately to his corps. Meade also told Sickles that he would ride out to assess the situation in person. Before departing for the Peach Orchard, Meade sent orders to Sykes, whose brigades were two miles to the rear, instructing him to move his corps forward as quickly as possible to anchor the Union left flank. The orders instructed Sykes to hold the position at all costs.

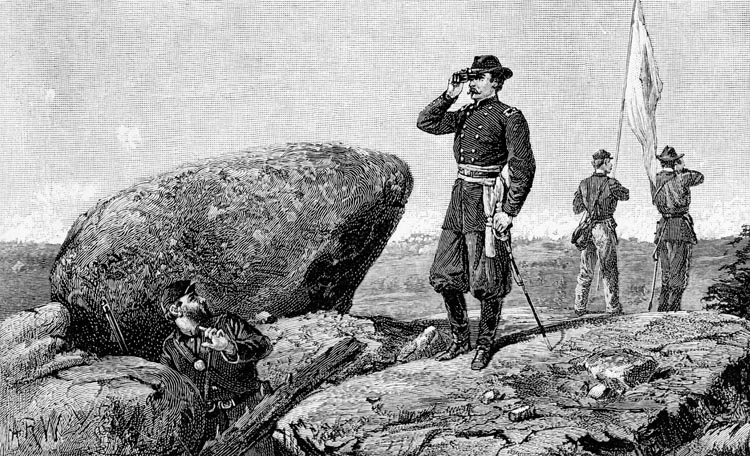

Meade also instructed army engineer Gouverneur K. Warren to go to Little Round Top to make sure it was well defended. Meade had instructed Sickles to defend it, and he had a sinking feeling that the inept corps commander had neglected that key responsibility. Riding to the top of Little Round Top where the flag signal station was located, Warren found no infantry force stationed there. He dispatched Lieutenant Ranald McKenzie of his staff to request that Sickles send one of his brigades to defend the key position. McKenzie then sought out Sykes and made the same request. Sykes sent a courier to hurry forward his First Division under Brig. Gen. James Barnes. When the staff officer ran headlong into Colonel Strong Vincent, who commanded Barnes’ Third Brigade, the spirited Pennsylvanian, who was the youngest brigadier in Meade’s army, volunteered his four regiments to defend Little Round Top. They would arrive in position just 15 minutes before Hood’s troops reached the rocky hilltop.

Meade’s temper had not cooled any when he saw the exposed position in which Sickles had placed his men. “General Sickles, this is neutral ground, our guns command it, as well as the enemy’s,” said Meade. “The very reason you cannot hold it [also] applies to them.” As Meade admonished Sickles, McLaws’ batteries opened fire on the Union III Corps infantry 400 to 600 yards away. When Sickles offered to return his corps to their original position, Meade wistfully said he wished that it would be possible; however, the Confederates were not about to let him. Meade knew all too well that the enemy would not miss an opportunity to attack an exposed corps.

While Rebel guns on Seminary Ridge and Federal guns in the Peach Orchard dueled, McLaws kept close watch on Hood’s progress to the south. Hood’s four brigades moved into position for their attack up Emmitsburg Road at 3:30 PM. They were deployed on high ground in Biesecker’s Woods east of the Emmitsburg Road. The front line consisted of Brig. Gen. Evander Law’s Alabama brigade deployed on the right and Brig. Gen. Jerome Robertson’s Texas-Arkansas brigade on its left. The supporting line, which was situated 200 yards behind the front rank, consisted of Brig. Gen. Henry Benning’s Georgia brigade on the right and Brig. Gen. George T. Anderson’s Georgia brigade on the left. Hood ordered the divisional batteries commanded by Captain James Reilly and Captain Alexander Latham to open fire in an attempt to locate the Union line.

No sooner had the Confederate artillerists begun firing their shells than they received counterbattery fire from the Federals. Captain James Smith’s Fourth New York Battery, consisting of six 10-pounder Parrot rifles, had unlimbered on the high ground at Devil’s Den in order to have a suitable field of fire against the Federals. He went into action against Hood’s guns as did Captain Judson Clark’s Battery B of the 1st New Jersey Light Artillery, which was deployed facing south beyond the east edge of the Peach Orchard.

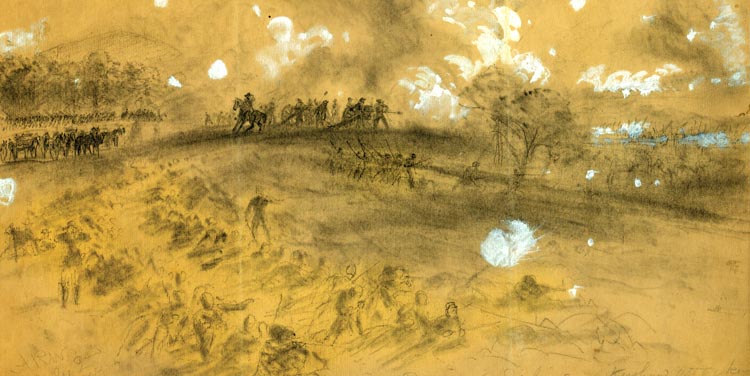

The Federal artillery fire rattled the troops in the front line of Hood’s division as they anxiously awaited orders to advance. Solid shot came screaming down to burst among the soldiers. A number of the waiting soldiers were killed in a gruesome manner. The Confederate officers ordered their men to lie prone, but this did not diminish the terror they felt.

Shortly after 4 pm Hood gave the order to advance. The broken terrain across which they attacked disrupted their advance. Law’s men rushed ahead at the double-quick, but their officers tried to slow their advance given that they had a lot of ground to cover before they struck the Union line.

Plum Run ran along the eastern periphery of this rough ground and meandered between Little Round Top on the east and Houck’s Ridge on the west. At the southern end of Houck’s Ridge was a jumble of boulders and rock slabs known as Devil’s Den. Just west of the northern end of Houck’s Ridge was a trapezoidal-shaped 40-acre woodlot belonging to farmer George Rose. The combination of rocky fields, woodlots, and orchards, nearly all of which were set off by stone fences, made it extremely difficult to maneuver large bodies of infantry in any coordinated fashion.

“Fix Bayonets, My Brave Texans; Forward, and Take Those Heights!”

Bloody fighting erupted in Rose’s Woods and Devil’s Den, where Birney’s left flank was anchored. The woods were situated directly south of the Wheatfield and 500 yards west of Little Round Top. Union Brig. Gen. J.H. Hobart Ward’s Second brigade of Birney’s division faced west. His line stretched from Rose’s Woods to Houck’s Ridge. Helping to anchor his left flank were Smith’s rifled guns.

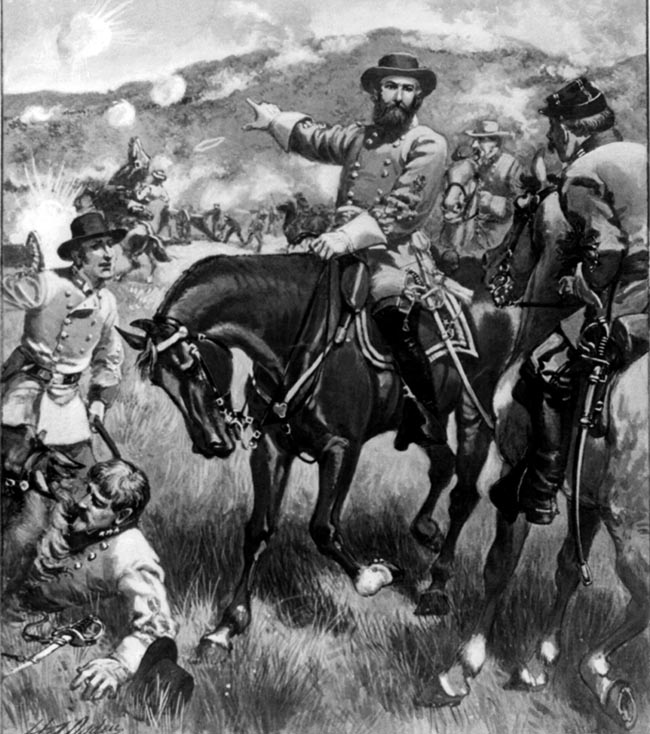

Hood took his customary position in front of the Texas brigade he had once commanded and gave a rousing speech. He then pointed to the east and said, “Fix bayonets, my brave Texans; forward, and take those heights!” The 2,600 Rebels in Hood’s front line streamed out of Biesecker’s Woods, but instead of advancing north along Emmitsburg Road as Lee had intended, they headed straight toward the two Round Tops.

The 2,800 troops in Hood’s second line, though, angled northeast toward Devil’s Den and Rose’s Woods. Because of the broken terrain, Robertson’s brigade soon became divided. The two right regiments, the 4th Texas and 5th Texas, swept forward toward Plum Run and Little Round Top. But the two left regiments, the 1st Texas and 3rd Arkansas, advanced against Ward’s brigade on Houck’s Ridge.

Hood was mounted on his horse 20 minutes into the attack in a small peach orchard on the Bushman Farm when a Union shell burst over his head. At the time he was holding the bridle with his left hand. A fragment struck the top of his forearm and exited just below his elbow. Hood reeled from the shock of the blow. His aides caught him just before he toppled from his saddle to the ground. Law assumed command of Hood’s division but had little influence on the progress of the attack.

Ward’s men initially held their ground, but the brigade became stretched to the breaking point when the brigadier shifted the bulk of his troops to support Smith’s endangered battery. As the fighting progressed, Smith lost three of his six guns to the attacking Confederates.

Birney’s hard-pressed brigade desperately needed help. He received one regiment from each of his other two divisions. But these reinforcements were not enough to stem the Rebel tide. Ward had no choice but to order his regiments to fall back. This allowed Benning’s Georgians to secure Devil’s Den.

Birney’s other two brigades were posted just south of the Millerstown Road that ran perpendicular to the Emmitsburg Road, crossing it at the Peach Orchard. French-born Brig. Gen. Regis De Trobriand’s Third Brigade of Birney’s division held the southern end of the Wheatfield and part of Stony Hill. Brig. Gen. Charles Graham’s First Brigade occupied a position from the southernmost edge of the Peach Orchard to the Trostle Farm Lane.

Anderson was getting his troops ready to advance when a messenger arrived from Robertson. The dispatch stated that the Texans needed immediate reinforcement. The four Georgia regiments advanced under Union artillery fire toward Rose’s Woods. “Had our advance been slow, they would have swept away all of us,” wrote Lieutenant John Reid of the 8th Georgia. “We understood that too well to loiter, and so we dashed on through small Wheatfields and over stone fences, filling up every gap made by a hit.”

Burling Withdraws from the Wheatfield; 8th and 9th Georgia Advance into the Gap

Once inside Rose’s Woods, the Georgians moved at an oblique angle facing northeast. Because De Trobriand had to send his 40th New York to assist Ward’s brigade on Houck’s Ridge, he received reinforcements in the form of the 8th New Jersey and 115th Pennsylvania from Colonel George Burling’s Third Brigade of Humphrey’s Second Division of the III Corps. De Trobriand’s right regiments, the 110th Pennsylvania and 5th Michigan, were deployed on the slope of Stony Hill behind Rose’s Run. Lt. Col. Charles Merrill’s 17th Maine on the brigade’s extreme left flank faced south behind a 30-inch-high stone wall in the southwestern corner of the Wheatfield. “Scarcely had we got into position when we heard the fearful Rebel Yell,” wrote Captain James Hamilton of the 110th.

The left wing of Anderson’s brigade made contact first. After 30 minutes of hard fighting, Burling, who was personally directing his regiments, withdrew them abruptly into the Wheatfield because he feared they were being flanked. This left a gap into which Colonel John Tower’s 8th Georgia advanced, along with elements of the 9th Georgia.

As they advanced into the gap, the Georgians were able to enfilade the right flank of the “Down Easters.” Merrill adroitly refused his right flank to negate the threat. Meanwhile, Colonel Francis Little’s 11th Georgia blazed away at the Maine infantry behind the stone wall. Fighting grew in intensity as the Georgians charged the wall. They sought to plant their colors on it, but they were soundly repulsed.

During the close-quarters fighting, Captain George Winslow’s Battery D, 1st New York Light Artillery, rendered invaluable artillery support to De Trobriand’s hard-pressed regiments. He had unlimbered his six Napoleon brass 12-pounder smoothbores on high ground in the Wheatfield 300 yards behind the brigade’s left flank. His gunners fired solid shot into the woods to disrupt the Georgians’ attack. The 8th Georgia charged the Union line three times and was flung back each time. The 9th Georgia lost its commander, Lt. Col. John Mounger, who took a minie ball in the chest and shrapnel in his bowels. After nearly an hour of fighting, Anderson withdrew his regiments to the southern edge of the woods.

During the lull after Anderson’s first assault, Brig. Gen. James Barnes, commander of the First Division of Maj. Gen. George Sykes’ V Corps, sent the brigades of Colonel William S. Tilton and Colonel Jacob Sweitzer into position on Stony Hill. During the lull in fighting that occurred after his brigade’s first attack, Anderson was struck by a minie ball in his right thigh. He was taken to a field hospital and Colonel William Luffman of the 11th Georgia took command of the brigade.

When all of Hood’s troops had been committed to battle, Longstreet decided it was time for McLaws to attack. Colonel Cabell, McLaws’ artillery chief, ordered his gunners to stop firing. He then ordered three guns fired in quick succession as the prearranged signal for the infantry to advance. As soon as this was done, the guns resumed their fire.

Victims of a Fatal Blunder

The arrangement of McLaws’ division mirrored that of Hood’s division. McLaws was to attack on a two-brigade front with Brig. Gen. Joseph Kershaw’s South Carolina brigade on the right supported by Brig. Gen. Paul Semmes’ Georgia brigade. On the left was Brig. Gen. William Barksdale’s Mississippi brigade supported by Brig. Gen. William Wofford’s Georgia brigade. The attack was to be “en echelon” formation with Kershaw advancing first with Semmes following behind him. Kershaw intended to have the center of his brigade strike Stony Hill.

Hunt had moved additional Federal batteries into position along the Millerstown Road that divided the northeastern portion of the Wheatfield from Trostle’s Woods. These guns opened fire on Kershaw’s South Carolinians who were passing across their front. Kershaw’s three left regiments wheeled north. They passed the stone buildings of the Rose Farm in an attempt to storm the Union guns. But an order to move by the right flank caused the three regiments to veer to the right away from the enemy guns. The Federal gunners who were preparing to pull their guns out of harm’s way now opened up with a vengeance. “Hundreds of the bravest and best men of [South] Carolina fell,” wrote Kershaw. “[They were] victims of this fatal blunder.”

Meanwhile, the rest of the Kershaw’s brigade advanced on Stony Hill. As they did, they joined the left regiments of Anderson’s brigade engaged against the Federals.

Through the smoke and dust that clouded the field the bluecoats on Stony Hill could see in the distance a gray line with battle flags fluttering advancing toward them. The 17th Maine braced for another attack behind their stone wall. Anderson’s Georgians surged forward once again in a bid to capture the wall.

Barnes grew deeply concerned over the position of his troops on Stony Hill in the face of McLaws’ attack. He therefore ordered both brigades to withdraw through the Millerstown Road and take up a new position in Trostle’s Woods. With casualties mounting and Barnes’s two brigades withdrawn, De Trobriand had little choice but to order his brigade to fall back as well. For this reason, the 17th Maine abandoned the stone wall for which it had shed so much blood.

Winslow’s Napoleons continued to hammer away at the Rebels. The 115th Pennsylvania also poured its fire into Anderson’s troops. Minie balls whipped through the wheat stalks, felling horses and gunners as Kershaw’s men fired into Winslow’s battery. Winslow gave the order to withdraw the guns to the Trostle Woods. In a herculean effort, his men managed to save all six pieces.

With the Wheatfield and Rose Woods in Confederate hands, the Federals rushed fresh troops to the sector. Brig. Gen. John Caldwell received orders to march his First Division of Hancock’s II Corps to support the V Corps. Leading the column was Colonel Edward Cross’s First Brigade. The other brigades in order of march were Colonel John Kelly’s Second Brigade (Irish Brigade), Colonel John Brooke’s Fourth Brigade, and Brig. Gen. Samuel Zook’s Third Brigade.

Cross pushed into the Wheatfield and about halfway across traded fire with Anderson’s Georgians positioned along the edge of Rose Woods. Cross was preparing his men for a charge when a Rebel sharpshooter shot him. While Cross was being carried from the field, Sergeant Charles Phelps killed the enemy sharpshooter. Cross succumbed to his wound the following day.

Cross’s bluecoats advanced steadily. On their right, the Irish Brigade kept up a spirited fire with its emerald flags flapping. But the advance of Zook’s companies was slowed considerably by the retreating troops of the V Corps. “If you can’t get out of the way, lie down and we will march over you,” shouted Zook from his horse.

Zook’s and Kelly’s brigades moved against the graybacks on Stony Hill. They met fierce resistance from Kershaw’s South Carolinians. Some men from both the 3rd and 7th South Carolina fired at Zook as he rode up the slope of Stony Hill. Minie balls ripped into his shoulder, chest, and stomach, mortally wounding him.

Kershaw requested that Semmes move his men into the gap between his own brigade and Anderson’s troops. As Semmes led his men forward in a charge, he was mortally wounded in the thigh. He died eight days later. The arrival of Caldwell’s division overwhelmed Kershaw’s brigade. Realizing his men could not hold their position, Kershaw ordered his men to withdraw in stages to the Rose Farm.

Confederate prospects worsened when Caldwell sent Brooke’s brigade into the fray. Advancing quickly across the Wheatfield, the Yankees came under enemy fire. Brooke ordered a bayonet charge, which succeeded in evicting Anderson’s Georgians from the Wheatfield. Reaching the western edge of Rose’s Woods, Brooke’s muskets came to a halt as Confederate resistance stiffened. For the time being, the Wheatfield and most of Rose’s Woods were back in Federal hands.

While Kershaw’s and Semmes’ brigades had advanced, Barksdale grew increasingly impatient for Longstreet’s signal to send his troops into battle. His brigade was taking casualties from the six Napoleons of Captain John Bucklyn’s Battery B, 1st Rhode Island Light, as well as a two-gun section of Captain James Thompson’s Pennsylvania Battery on the Sherfy Farm. “I wish you would let me go in, general,” said Barksdale. “I would take that battery in five minutes.” But Old Pete would not be rushed. “Wait a little, we are all going in presently,” he said.

Barksdale Advances on the Peach Orchard

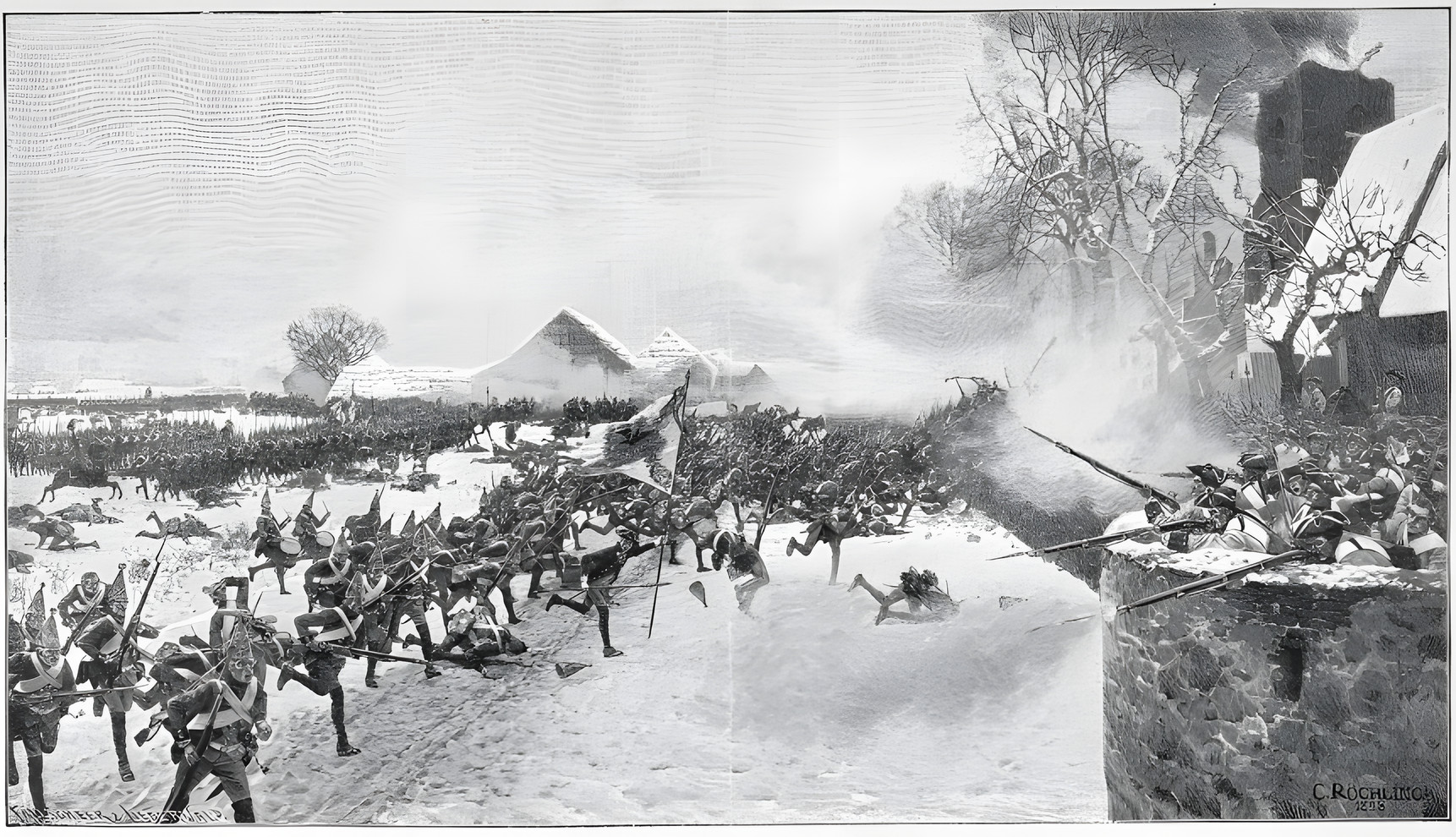

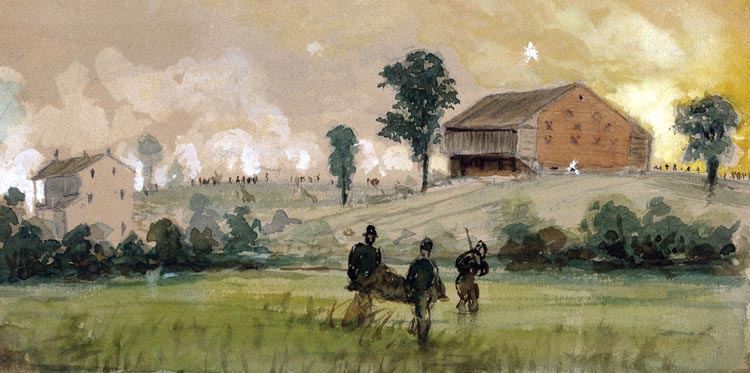

Barksdale got his orders to advance on the Peach Orchard. Barksdale’s 1,600 Mississippians were as anxious to get moving as their commander. Climbing over a stone wall at edge of Pitzer’s Woods, the men advanced in two lines that stretched for 350 yards. Barksdale, the fire-eating secessionist former congressman, waved his saber over his head and led his men forward. The moved with such momentum that they smashed through the wooden fences on both sides of Emmitsburg Road as they advanced.

Brigadier General Charles Graham’s brigade held the Peach Orchard. Only four of his six Pennsylvania regiments, totalling 1,000 men, were in position along the Emmitsburg Road to defend against Barksdale’s attack. As Barksdale’s Magnolia Staters advanced, the Federal artillery blew gaping holes in their ranks. To lessen the time they had to spend under the cannon fire, Barksdale ordered his men to double quick. The Mississippians let out a Rebel yell as they rushed toward the enemy.

When Barksdale’s soldiers came to within 40 yards of Bucklyn’s guns, they halted and fired a deadly volley that felled a good number of horses and gunners. The 114th Pennsylvania Zouaves advanced past the battery as Bucklyn issued orders to his men to limber up and withdraw to the rear. The 57th and 105th Pennsylvania Regiments also advanced. Graham requested aid from two brigades of Humphrey’s division nearby that not yet been engaged. The 73rd New York Zouaves of Colonel William Brewster’s Second Brigade dashed forward and took up position behind the 114th Pennsylvania.

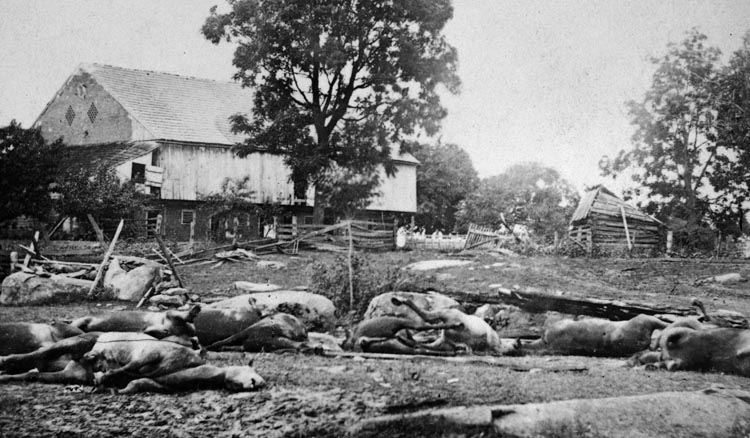

Barksdale’s charge swept like a storm tide over Graham’s brigade. Colonel Benjamin Humphreys directed his 21st Mississippi to attack Colonel Andrew Tippin’s 68th Pennsylvania holding the left flank of Graham’s brigade in Sherfy’s Peach Orchard. Colonel William Holder’s 17th Mississippi joined the attack on the hapless Pennsylvanians by assailing the regiment’s right flank. Heavily outnumbered, the 68th Pennsylvania lost half its men in a matter of minutes.

Having smashed the 68th Pennsylvania, Barksdale swept the rest of Graham’s brigade from the field. The 57th Pennsylvania, which had been defending the Sherfy farm buildings, broke and fled east toward Cemetery Ridge. Barksdale’s men rounded up hundreds of Pennsylvanians from Graham’s shattered brigade. One of the prisoners was Graham, who had been wounded by shrapnel in the hip and shot in the upper body.

Deployed facing south at the Peach Orchard were three Union regiments from three different brigades. Barksdale’s Mississippians were astride the right flank of the line formed by the three regiments. One of these regiments, Graham’s 141st Pennsylvania, tried to slow the Confederate advance and lost three-quarters of its men in short order.

Porter Alexander ordered six Confederate batteries to advance to support McLaws’ division. Meanwhile, Barksdale’s Magnolia Staters pushed east toward Abraham Trostle’s farm where Sickles had his headquarters. Confederate guns bombarded the Trostle Farm. Sickles was riding his battle line when a shell struck his right leg. He had enough presence of mind to order a tourniquet fashioned from a saddle strap. He was whisked away in a wagon. A surgeon amputated his leg just above the knee. When Meade learned that Sickles was out of the battle, he gave Hancock command of Sickles’ beaten corps.

While Barksdale crushed Graham’s brigade, Wofford sought to exploit the gap between Graham’s brigade in the Peach Orchard and De Trobriand’s brigade on Stony Hill. The arrival of Wofford’s Georgians breathed fresh life into the brigades of Kershaw, Semmes, and Anderson.

Barksdale’s Men Get Within a Quarter Mile of Cemetery Ridge

The Federals holding Stony Hill and the Wheatfield were in serious danger of being outflanked. Barnes sent Sweitzer’s brigade to assist Caldwell. Sweitzer’s 1,000 Yankees advanced through the Wheatfield as the hard-pressed troops on Stony Hill began to fall back. The Confederates caught Sweitzer’s brigade in a murderous crossfire, forcing them to withdraw as well.

As Caldwell’s division withdrew east from the Wheatfield, Sweitzer’s brigade wound up covering its retreat. Rebels streamed into the trampled wheat and took possession of the field. The only Union forces left in good order on the west side of Plum Run were two small brigades of U.S. Army regulars deployed in two lines south of the Millerstown Road. They belonged to Brig. Gen. Romeyn Ayres’ division of the V Corps.

Farther north Barksdale exhorted his left regiments to press their attack against two brigades of Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphreys’ Second Division of the III Corps. Adding weight to his attack were the fresh Alabama regiments of Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s brigade of Richard Anderson’s division.

Colonel Humphrey’s 21st Mississippi moved east along Millerstown Road toward four Federal batteries totaling 22 guns facing south. The Federal artillerymen limbered up their guns and rode east as minie balls zipped through the air, felling men and horses alike.

Captain John Bigelow’s 9th Massachusetts Light Battery was positioned the farthest east. Bigelow knew that once his six Napoleons stopped firing the Rebels would be on him. He fired canister that shredded the attacking Confederates. Instead of rolling the guns back into position, he allowed their recoil to move them steadily back. Having reached the Trostle Farm in this manner, he ordered his guns limbered up. It was now 6 pm and Barksdale’s men were only a quarter mile from Cemetery Ridge.

When he reached the Trostle Farm, Bigelow had gained enough distance from the attacking Confederates to limber up his guns. Before they were limbered, Lt. Col. Freeman McGilvery, his commanding officer, arrived and ordered him to hold his position at all hazards. Bigelow then ordered his gunners to load double canister. McGilvery then rode off to scrape together guns to thwart the Confederate advance toward a three-quarter-mile gap on Cemetery Ridge. The Mississippians charged his battery and got among the guns. Bigelow was able to save only two of them. Shortly afterward, Colonel Humphrey halted his Mississippians having realized they had advanced too far to the front and were unsupported.

A short distance to the north, Barksdale was out front leading his troops as they attacked northeast. “Forward men! Forward!” he cried, pointing his sword at the Yankees on Cemetery Ridge. When his regimental commanders requested that he break off his attack and regroup, he dismissed the idea. The Mississippians got as far as the west slope of the ridge, but by then Hunt had massed 40 guns to thwart them. Meanwhile, Hancock plugged the gap in his line with Colonel George Willard’s brigade of Brig. Gen. Alexander Hays’ Third Division of the II Corps.

Willard’s New Yorkers launched a vicious counterattack. The 126th New York wanted revenge for having been forced to surrender at Harpers Ferry during the Antietam Campaign. They came on shouting “Remember Harpers Ferry!” Willard fell in the counterattack, but his men succeeded in repulsing the Mississippians. Barksdale was mortally wounded trying to rally his men. Shot in both legs and the chest, he was captured by the Yankees. He died before morning. Of the 1,600 Mississippians in his brigade, 789 were killed, wounded, or missing after the attack.

Longstreet takes the Devil’s Den and the Peach Orchard; the Union Keep Little Round Top and Cemetery Ridge

The fighting then shifted north as Maj. Gen. Richard Anderson’s troops advanced against the Federals. Only half of Anderson’s 7,000-strong division went into action, though. Both Longstreet and his fellow corps commander Lt. Gen. A.P. Hill thought the other was responsible for overseeing Anderson’s attack.

As for Anderson, he did not provide strong direction. Before Lee’s reorganization of the Army of Northern Virginia, Richard Anderson had commanded a division in Longstreet’s I Corps, and Old Pete always kept a close eye on his division commanders. Anderson gave his brigade commanders too much independence. One of Anderson’s brigade commanders, Brigadier William Mahone, never committed his Virginia regiments to the attack, claiming he had orders to sit tight. Despite these problems, Brig. Gen. Ambrose Wright’s Georgians gained the crest of Cemetery Ridge. But when no reinforcements came to support him, Wright withdrew his men rather than have his brigade destroyed.

Longstreet had captured Devil’s Den, the Peach Orchard, and the Wheatfield, but none of these areas were key ground. Importantly, Hancock and Sykes retained Little Round Top and Cemetery Ridge. Of the 22,000 Confederates in three divisions that participated in the attack against the Union left on July 2, 7,000 were casualties. The butcher’s bill for the Union III Corps amounted to 4,323 casualties from the 10,750 that went into battle that day.

Confederate valor was never in question. Taken on the whole, the troops of Hood’s and McLaws’ divisions fought heroically on July 2. Three Confederate divisions took on six full Union divisions and parts of three more divisions in an attack that lasted for four hours. But the Yankees no longer panicked and fled the field in the face of a Confederate flank attack as they had at Second Manassas and Chancellorsville.

Longstreet told McLaws after the war that his intention had not been to press the attack on July 2 if the enemy’s position proved too strong for his two divisions. But Old Pete did not stop the attack. He delighted in seeing his troops smash Sickles’ III Corps. It was “the best three hours’ fighting ever done by any troops on any battlefield,” he said.