By Kevin M. Hymel

On the morning of December 19, Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., prepared his Third Army for a battle raging north of him—the Battle of the Bulge. Three days earlier, three German armies had burst out of the Ardennes Forest in Belgium and Luxembourg and smashed into Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army.

At first, Patton tried not to get sucked into the campaign, but when Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, commander of 12th Army Group, showed Patton a map of the enemy’s progress against Hodges, Patton snapped into action, reorienting two of his corps north while keeping one facing east.

That morning, as he prepared to depart his headquarters in Nancy, France, and head to Bradley’s headquarters in Verdun to meet with him and General Dwight D. Eisenhower to figure out how to meet the German onslaught, Patton ordered Maj. Gen. Walton Walker’s XX Corps to go on the defensive. He ordered Van Fleet’s 90th Infantry Division to pull out of Dillingen and create a defensive front on the west bank of the Saar River.

Since the Germans had knocked out the bridge, it took the men of the 90th three days to complete the maneuver. One of the division’s battalion staffers wrote in a unit log, “This is the first time this Battalion ever gave ground and even though it was a strategic retreat rather than tactical, it still hurt.”

After making the XX Corps arrangements, Patton held a 7:30 a.m. meeting that included Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy, commander of XII Corps and Maj. Gen. John Millikin, commander of III Corps, and their collective staff. He began with a rousing, yet serious and professional speech equal to the moment:

“Third Army has a chance to go down in history as the greatest Army of this war,” Patton said. “We are going to attack the enemy on his exposed flank and end the war this side of the Siegfried Line. That is going to kill the Germans coming at us, instead of going after the bastards holed up in bunkers and pillboxes.”

He cautioned them all about getting too excited and reminded them to remain professional. “Third Army is what it is because you have always done the impossible as of yesterday. We are going to do it again.” He ended his remarks by reminding everyone that they would not be taking any German SS prisoner, implying their death.

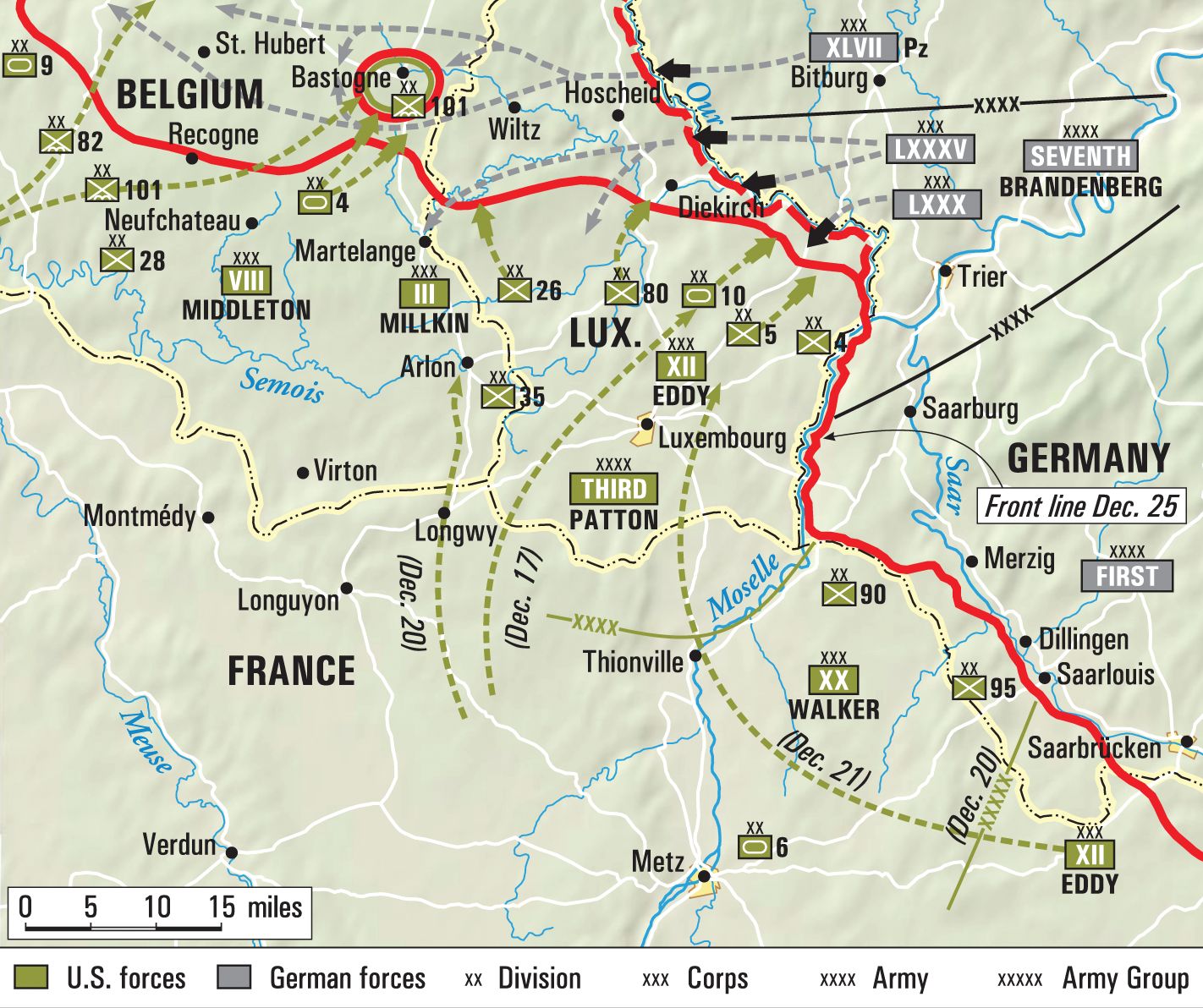

After telling them about Bradley’s order to turn three of his divisions north, Patton explained his plans by making a rough draft map. He began by saying that Maj. Gen. Troy Middleton’s VIII Corps would come under Third Army command and then explained how he intended to reach him: both Maj. Gen. Willard Paul’s 26th and Maj. Gen. Horace McBride’s 80th Infantry Divisions would head west to Metz, while Maj. Gen. Hugh Gaffey’s 4th Armored Division would head west to Pont-à-Mousson.

All three divisions would then head north to Longwy, where Millikin would decide the direction of their attack. Eddy’s XII Corps, fighting in the south, would have to swing north and take over Third Army’s eastern front.

In addition, Major General Leroy Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division and Maj. Gen. Robert Grow’s 6th Armored would head west to Thionville and Metz, respectively, and then head north to Luxembourg City. To cover the corps-sized gap, Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army would stretch itself to cover Third Army’s southern sector. Both Longwy and Luxembourg City provided the best roads to continue north into the Bulge.

Walker’s XX Corps, which would change from Patton’s northernmost corps to his southernmost, would be left out of the drive and would instead hold Patton’s southern flank. Walker, who thought he was getting the most important role of the campaign since his corps was closest to the fight, had been relegated to placeholder.

Patton also stressed that Eisenhower had told Bradley, “I want to put as many troops as possible under Patton.”

For the main thrust into the Bulge, Patton developed three possible axes of attack, each with a well-coined code name. “Cent” called for an attack north through Diekirch, cutting the Bulge at its base. “Nickel” called for an attack from Arlon, 13 miles north of Longwy to Bastogne. “Dime” would be an attack against the tip of the Bulge, wherever that might be. Patton jotted the three codes down on a piece of paper and handed it to Lt. Gen. Hap Gay, his chief of staff.

Once Patton knew what Eisenhower and Bradley wanted him to do, he would simply call Gay and give him the chosen code word. He preferred Cent, cutting the Bulge off at its base, but told the staff to get cracking on all three contingencies. He considered his plan inspired but warned the staff, “Only they [SHAEF] don’t think that way up there. [They’re] not made that way.”

Before Patton met with his staff, up north three German divisions, two panzer and one infantry, clashed with the smaller combat teams of Desobry, Cherry, and O’Hare in the snow-covered and battered towns of Noville, Longville, and Wardin, respectively.

The fighting had started at 5 a.m. and continued throughout the day, despite blinding fog that only lifted periodically. American infantry, tank, and tank destroyer crews fought desperately as the paratroopers from the 101st Airborne marched through Bastogne and fanned out to reinforce the teams, helping form Bastogne’s perimeter.

Further north, the two surrounded regiments from the 106th Infantry Division also fought desperately in hopes of relief. The U.S. military’s greatest strength, ground-support aircraft, played no role in the fighting, with all planes grounded in the pea-soup fog.

“Sure looks like the devil is helping his own,” Patton said as he glared up at the low-lying clouds and fog over Nancy. He and his staff, consisting of Major Charles Codman, Colonel Paul Harkins, Colonel Walter Muller, and Lt. Col. Richard Stillman, climbed into two armored jeeps with mounted .30-caliber machine guns, side doors, and extended mud flaps, and headed out over snow-covered roads for the 60-mile trek to Verdun.

After about an hour and a half, the jeeps drove through Verdun, turned off Goubet Van Heeghe Avenue, entered the gate, and drove through the muddy courtyard to the main entrance of Bradley’s headquarters. Two MPs greeted them as they ascended the stairs to the entrance.

Bradley had arrived first from Luxembourg City, having navigated roads filled with escaping civilians. When British signal equipment blocked the road, he impatiently leaned out the window and shouted at them to move. Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers, the commander of 6th Army Group, arrived in a sedan escorted by two MP jeeps. With him were Brig. Gen. Reuben E. Jenkins and Major Eugene Lynch, his operations and intelligence officers.

Eisenhower and British Air Marshal Arthur Tedder, Eisenhower’s deputy, arrived in a Packard and hurried up the stairs and into the building. Despite the seriousness of the situation, Eisenhower smiled as he shook hands with Bradley’s staff. The two men then ascended to the second floor and entered the room where the other officers awaited them. Other American and British officers arrived and filed upstairs.

From Eisenhower’s staff came Lieutenant General Walter Bedell “Beetle” Smith, British Air Marshal James Robb, and British Colonel James Gault. Members of Bradley’s staff were also on hand, as were numerous lower-ranking officers. Missing from the meeting were Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, who had refused to attend any meetings unless they were held at his headquarters, and Hodges, who was busy fighting the onrushing Germans.

Usually, General Freddy de Guingand represented Montgomery at such meetings, but he was stuck in London, unable to fly to the Continent due to heavy fog. Hodges was in contact with Bradley, although the communications link was at times poor and subject to interference. When Major Generals Harold “Pink” Bull and Kenneth Strong, also from Eisenhower’s staff, entered the room, Ike said, “Well, I knew my staff would get here—it’s only a question of when!”

Altogether, there were at least 16 men in the freezing room, 12 Americans and four British; others waited outside. The men kept their coats on to ward off the cold, which overwhelmed a small coal-burning stove in the corner. The room filled with smoke as the men puffed away at cigarettes, cigars, or pipes. Coffee and sandwiches were served. The room contained rows of simple wooden folding chairs in front of a huge map that almost took up the whole wall.

Patton paced the room, puffing on a cigar. Despite his upbeat attitude, his face was etched with grim concern. Bradley looked stern. He had spent the morning reviewing reports of deeper German penetrations, trying to get a picture of the confusing situation.

Along with the bad news about the 106th Division’s two surrounded regiments, he had also been following the German drive on Bastogne and reports of enemy buzz bombs (V1s) dropping on Liège. But the Americans were fighting back. Engineers were destroying bridges to prevent the Germans from reaching Hodges’s headquarters in Spa.

Along with Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe’s 101st, Maj. Gen. James Gavin’s 82nd Airborne had reached the 7th Armored Division and was driving east, looking for the enemy. But when Bradley received a report that air operations had been stymied by bad weather, he just shook his head.

Only Eisenhower seemed to be in a good mood. Seeing old friends and acquaintances lifted his spirits. He started the meeting by declaring, “The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster. There will be only happy faces at this conference table.”

Patton, happy to see his commander in such an aggressive mood, blurted out, “Hell, let’s have the guts to let the bastards go all the way up to Paris. Then we’ll really cut ’em off and chew them up.”

The exchange broke the tension in the room, if only temporarily. Eisenhower, remaining serious, told everyone that the enemy must not be allowed to cross the Meuse River separating France from Belgium.

General Strong stepped in front of the wall map and presented the situation as well as Eisenhower’s headquarters knew it. He told them that the Germans had launched an all-out attack aimed at Brussels in the hopes of splitting the British and American armies. While the Allies were holding firm on both shoulders of the penetration, in between, “German units were pushing ahead and already bypassing the resistance at St. Vith and Bastogne.”

Strong would later admit that while his predictions seemed gloomy, everyone reacted with surprise, even though he was only repeating, according to him, “with greater confidence and in more detail,” what he had told Eisenhower on the afternoon of December 16.

Strong also presented four possible objectives the German might consider to reinforce their offensive: the almost defenseless city of Namur on the Meuse River, 75 miles northwest of St. Vith, the next major city on the way to Brussels; the German city of Monschau, north of St. Vith, which, if the Germans captured it, would widen the mouth of the offensive; a secondary attack from Trier; and lastly, an attack somewhere north of Lt. Gen. William Simpson’s Ninth Army (which meant a pincers movement), although Montgomery had enough forces to deal with such an attack.

Eisenhower wanted to hold the shoulders of the German breakthrough and then attack the Bulge from both sides. While the first part of his idea was sound, the second part would be more difficult, with Hodges busy pulling units out of the Roer River line and sending them piecemeal into the German flank. Bradley worried that Hodges’ line would crack and the Germans would flood across the Meuse into France.

There was, however, no talk of defense—pulling back to the Meuse was not an option. Bradley’s operations officers considered that alternative “too unthinkable to merit consideration.”

Bradley proposed that Devers gradually take over Patton’s southern front so Patton could focus on an immediate counteroffensive. The gradual takeover would prevent any confusion with supplies since Devers’s supplies came from southern France and Patton’s from the northern part of the country. Bradley explained that, for the northern side of the Bulge, he was adding two divisions to Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’s VII Corps and would expand Collins’s sector to allow Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow’s V Corps to focus on the northern shoulder.

Eisenhower asked Devers how much of Patton’s southern sector he could take over. After Devers told him that a salient in his lines—the Colmar pocket—restricted him from taking over Patton’s entire zone, Eisenhower told him to reach out as far as possible to his left—about halfway between Saarlautern and Saarbrücken—while giving Patton every division he could spare.

Devers was not happy about relinquishing the offensive and losing divisions, but was resigned to dealing with the crisis at hand. Eisenhower permitted him to give ground if necessary to keep his forces intact. He did the same for Eddy, telling Patton he could fall back in the Saar region if necessary.

Throughout the meeting Patton sat still, only commenting that he needed replacements and suggesting using the soldiers from three recently arrived infantry divisions as replacements for his depleted army. Bradley agreed and said he would provide Patton with a portion of the men that were to go to Hodges and Simpson.

Bull recommended shipping nine infantry regiments from the newly arrived 42nd, 63rd, and 70th Infantry Divisions directly to Bradley, for a total of 2,700 soldiers. He even suggested sending the regiments of the 66th Infantry, which was scheduled to relieve the 94th Division. All that was still not enough for Patton. He recommended using untrained logistics personnel.

Devers, too, asked for more troops, but not as forcefully as Patton. “No,” Eisenhower responded, “I won’t admit we are that near beaten.”

Patton quickly shot back, “We will be if we don’t get more.”

Bradley expressed concern about Bastogne and its vital road net. Eisenhower agreed that protecting it should be the goal. The generals also discussed using Third Army to cut off the Bulge at its base, but with the threat of an additional German thrust out of Trier, Eisenhower decided that for the immediate future they needed to simply strengthen the southern shoulder while driving for Bastogne.

He would later say of his decision, “I firmly believed that by coming out of the Siegfried [Line] the enemy had given us a great opportunity which we could seize as soon as possible.”

Eisenhower turned to Patton. “George, you’re going to have to abandon your plan to break free of the Siegfried Line and attack north,” he told him. “I want you to go to Luxembourg and take charge.”

Patton did not miss a beat, replying, “Yes, sir.”

Eisenhower needed to know how long it would take him to get back to Nancy, pack, get the word out to his staff, and move his headquarters 50 miles north to Luxembourg. “When can you start up there?” he asked.

Patton claimed he would be ready on December 21, Eisenhower accused him of being “fatuous,” and worried that Patton would attack before he had a large enough force. To guard against that, Eisenhower specifically told Patton, “If you try to go that early, you won’t have all three divisions ready and you’ll go piecemeal. You will start on the 22nd and I want your initial blow to be a strong one! I’d even settle for the 23rd if it takes that long to get three full divisions.”

Patton responded to Eisenhower’s request by telling him, “I can put on a spoiling attack with three divisions in three days or a more concentrated attack by six divisions in six days.” Eisenhower said, “We can’t wait for six days. When can you get moving?” Patton turned to Colonel Harkins and said, “We can do that.” To which Harkins responded, “Yes, sir.”

Patton turned back to Eisenhower. “If you’ll let me go to a phone we’ll be on the road in less than an hour.” (One account had Patton responding, “I’ll not only attack, I’ll shove von Rundstedt down Montgomery’s throat.”)

Patton’s claim that he could rapidly launch an attack toward Bastogne in three days caused quite a bit of commotion in the room. As Codman remembered it, “There was a stir, a shuffling of feet, as those present straightened up in their chairs. Patton later wrote, “Some people thought I was boasting and others seemed pleased.” Some of the British officers openly laughed. Others looked up excitedly. One staff officer remembered, “It almost knocked me out of my chair.”

Patton was promising to turn part of his army 180 degrees north and attack in only three days. Yet, it was not impossible. He would use Millikin’s III Corps with three divisions—Gaffey’s 4th Armored, Paul’s 26th, and McBride’s 80th—which were behind the lines and had been resting (until he had alerted them the night before). The hard part would be getting the second corps, Eddy’s XII, disengaged and heading north. Only Irwin’s 5th Infantry was off the line in Eddy’s zone. Patton knew if he could launch his initial attack quickly, he would entirely surprise the Germans.

Eisenhower still worried the attacking force was too weak and that Patton had underestimated the strength of the German assault. Tedder interjected, suggesting Patton turn over Walker’s XX Corps to Devers, but Patton refused, wanting to use Walker’s zone as a possible rest area for his attacking divisions. Walker was also closest to the German city of Trier. With Trier captured, he could race across the German Palatinate region, something Patton yearned to return to.

Eisenhower instructed Patton to advance by phase lines, keeping all his forces tightly together and avoiding wasting his divisions’ strength through dispersion. But where would Patton attack? While Patton wanted to attack the German offensive at its base, Bradley felt that by attacking toward Bastogne, Third Army would still threaten the enemy’s rear.

Finally, Eisenhower assured everyone in the room that he would urge Montgomery to launch his own attack from the north as soon as the “German blow in that sector had spent itself.”

Patton’s three-division assault did not surprise Bradley. The two had discussed it the night before when he told Patton about the situation. He was surprised, however, at the speed with which Patton was promising to do it. When he asked about the feasibility of turning an Army around and going on the attack in two days, Patton responded by lighting a cigar and pointing at the bulge on the battle map.

“Brad,” he told his commander, “This time the Kraut’s got his head in a meatgrinder.” Then he closed his hand into a fist, “and this time I’ve got hold of the handle.”

When Patton predicted he could reach Bastogne in his first rush, Eisenhower told him that as long as he was advancing he would be satisfied. Bradley worried the attack would be hard to disguise, so he turned to Lt. Col. Ralph Ingersoll of the 23rd Headquarters Special Troops, the deception unit that had worked so well for Patton in Brittany and outside Metz, and asked him if there was anything he could do to keep the Germans from knowing where Patton would strike. Ingersoll promised to come up with something.

Eisenhower summed up the meeting in a telegram to Beetle Smith: “The general plan is to plug the holes in the north and launch a coordinated attack from the south.” He would leave the details to Patton.

Patton’s plan seemed to galvanize everyone in the room and they wanted to help. Two of Bradley’s logistics officers chimed in. Colonel Raymond Moses told Patton and Mueller that COMZ, the supply command for all forces in Europe, would cooperate fully on all transport and that they would keep up with Patton’s drive as closely as possible. Colonel William A. Barriger added that 10 truck companies were already on the way to Third Army and the leading trucks should be through Verdun that evening.

As the high-ranking generals and their staff filed out of the room, Patton was already in action. He called over to Harkins and ordered, “Telephone Gay, give him the code name [Nickel], tell him to get started. Then get back to Nancy yourself as soon as you can. You know what to do.”

He wasn’t finished. He turned to Codman and barked out more orders. “Codman, you come with me. Tell Mims (Patton’s driver) we start in five minutes—for Luxembourg. And telephone General Walker and tell him I will stop and see him in Thionville on the way.”

As they left the room, Eisenhower told Patton, “Funny thing, George, every time I get promoted, I get attacked.” Eisenhower was referring to the Kasserine Pass debacle in North Africa in early 1943, when German General Irwin Rommel punched the center of the American II Corps and sent it reeling back a hundred miles. The military disaster occurred merely days after Eisenhower had been promoted to full general.

It had been Eisenhower’s first crisis as a war commander and he reacted immediately, firing commanders, racing reinforcements to the front, and bringing in Patton to command II Corps.

Now, on the day the Germans launched the Battle of the Bulge, he learned that President Roosevelt had nominated him for the five-star rank of General of the Army.

“Yes,” Patton agreed, “and every time you get attacked, I bail you out.”

Historian Martin Blumenson called Patton’s claim to move his army in three days his sublime moment, but it was not. While it was dramatic and shocking, Patton’s real sublime moment came after he left the room, and lasted for the next three days as he turned most of his army north. It was one thing to claim he could pivot his army and go on the attack, it was another to deliver on the goods. And that he did.

He never returned to his headquarters in Nancy, instead moving directly to Luxembourg City. He would also be close to Bradley’s headquarters, where he would spend much of his time. When not meeting with Bradley or the Third Army staff, Patton would be out on the road, directing, cajoling and physically moving his troops north, despite the snow and freezing temperatures.

The Verdun meeting was also important to Eisenhower. In two hours he came to grips with his entire front and developed a plan of not just matching the German offensive but defeating it. Before the meeting he was using ad hoc methods to deal with the breakthrough; now he had an overall idea about the attack and how his forces would go about erasing the Bulge. It would be another week before the plan began to bear fruit, but the seed had been planted. In a way, Eisenhower and Patton were the star players of the meeting. Patton would lead the charge and Eisenhower would provide the means.

Would the Verdun meeting have been different had Montgomery attended? Possibly. The energy of Patton’s can-do spirit may have prompted him to come up with his own offensive from the north, committing British forces between the American corps for an assault aimed in the direction of Bastogne.

On the other hand, the meeting may have reinforced Monty’s attitude that Americans did not understand the European way of war and that Patton’s plan was unrealistic and foolhardy. Patton’s dynamic attacks in Sicily did not change Montgomery’s plans during that campaign at all.

In fact, the Verdun meeting might have simply entrenched Montgomery in his own battle plan to wait out the German offensive until it had spent itself. While that battle plan would have frustrated Eisenhower, at least his American commanders would have seen for themselves what Eisenhower was up against with Montgomery and what Patton had been complaining about for the last five months.

By the time the Verdun meeting ended, things had gotten worse for those freezing American soldiers. Around 4 p.m. the two surrounded regiments from General Jones’s 106th Division surrendered.

Further east, the spearhead of the German attack toward Antwerp, Battle Group Peiper, reached its high-water mark at Stoumont, 50 miles into the American lines but 30 miles short of its goal. It had been stopped by an American armored counterattack, but no one realized at the time that the Germans would get no further.

Around Bastogne, combat teams Cherry and O’Hare fought off repeated German armored attacks, while Team Desobry actually counterattacked in Noville with the help of a battalion of paratroopers from the 101st Airborne. The situation in Bastogne became serious enough for Middleton, the VIII Corps commander, to relocate his headquarters from Bastogne to Neufchâteau, 18 miles southeast. General McAuliffe took command of Bastogne.

Patton walked Eisenhower out to his vehicle while Bradley remained inside, calling Hodges on the phone for updates. As Eisenhower prepared to leave, a jeep rolled up and off jumped a sergeant from a medical battalion.

The sergeant did not approach Eisenhower and Patton for any medical crisis, instead he saluted and asked the two if he could have his picture taken with them.

They both agreed, with Eisenhower telling Patton, “George, move over and let the soldier in the middle.” He did.

This article is excerpted from Kevin Hymel’s latest book, Patton’s War: An American General’s Combat Leadership, Volume 2: August—December 1944, published by University of Missouri Press. The author is a contract historian for Arlington National Cemetery. He previously served as a historian for the U.S. Army Combat Studies Institute’s Afghan Study Group and U.S. Air Force Medical Service and Chaplain Corps. Mr. Hymel has also served as this magazine’s research director and is a frequent contributor.

After the Germans had been defeated, in the Battle of the Bulge, most everyone was rewarded by Eisenhower, but not Patton.

Patton got the only reward he wanted, dead Germans and bringing the end of the war closer.