By Earl Echelberry

By the early 1770s, with a full century of settlement already behind it, Charleston, S.C., had come into its own as a thriving urban center. Its 12,000 residents, half of whom were white, looked optimistically to the future. It was a young society, enthusiastic and on the move, a mixture of many nationalities and cultural styles.

Increasingly, however, Charleston’s planters, merchants, and aristocrats chafed under the distant domination of Great Britain. Needing funds to maintain its far-flung army and navy after the French and Indian War, Britain had heightened its confiscatory policies of taxation on the colonies and its restriction of American manufacturing. As the years went by, the Crown’s directives accumulated: the Sugar Act, the Stamp Act, the Quartering Act, the Townshend Acts, the Tea Act. Charleston’s large body of artisans, many of whom operated their own enterprises, took a dim view of these controls. Clothiers and carpenters, chandlers and coach makers, bricklayers and gunsmiths all hated a system that jammed competing British products down their increasingly unwilling throats.

The antagonisms took on a momentum of their own. In September 1774, five Charleston representatives journeyed north to Philadelphia to take part in the First Continental Congress. A month later, Charleston threw a Boston-style “tea party” of its own where self-styled Patriots strongly if unsubtly suggested that local importers of British East Indian tea might want to dump that tea into the harbor—which they did posthaste. The rest was stored in moldy vaults in the basement of the Charleston Exchange and left to rot.

Increasingly, battle lines were being drawn. A Provincial Congress controlled by Patriots met in January 1775 and assumed legislative authority for the colonies. In April 1775, the American Revolution was ignited in Lexington and Concord, Mass. In May, the British absorbed tremendous losses in taking Bunker Hill (actually Breed’s Hill) in Boston. That same month, Charlestonians were outraged to learn that the British government was considering a plan to recruit South Carolina Indians and slaves to fight against the white colonists. The report proved false, but it sent a shock wave of fear through the city, and a Council of Safety was appointed to regulate Charleston’s defense. An incautious free man of color, Thomas Jeremiah, was lynched for saying out loud that he would gladly help the king’s forces if they came to South Carolina.

Patriots and Loyalists, rich men and poor, all realized that for better or worse the time for fighting was now upon them. Fiery meetings were held across the state, with pro- and anti-British spokesmen taking turns denouncing each other’s perfidy. A newly arrived immigrant from Yorkshire, Thomas Brown, earned the unwelcome nickname “Burnfoot” when members of the rebellious Sons of Liberty tarred and feathered him, held his feet over the fire—he lost two toes—and fractured his skull with a rifle butt. Embittered by his experience, Brown would become one of the Patriots’ most implacable foes. Two other prominent South Carolina Tories, Laughlin Martin and James Dealy, were also tarred and feathered and paraded through the streets of Charleston. Dealy’s specific offense had been to declare in a toast, “Damnation to the [Secret] Committee and their proceedings.”

Throughout the summer and fall of 1775, Charlestonians debated revolution within their city and in the surrounding backcountry. William Henry Drayton, a member of the Council of Safety and one of the so-called “rice kings” who ruled South Carolina’s social, political, and financial worlds, took the lead in brokering a truce with the state’s Tories. The subsequent Treaty of Ninety Six (named after the backcountry village where it was signed) called for the punishment of anyone molesting or harming a Tory, while the Tories agreed not to assist British troops in any way within the state. Meanwhile, the Patriots raided the royal power magazines outside Charleston, seizing some 1,600 pounds of powder, and made off with 800 muskets and 200 cutlasses from the armory in the basement of the statehouse.

Predictably, the Treaty of Ninety Six did not hold for long. The Council of Safety arrested several leading Tories on trumped-up charges, and the Tories responded by capturing a supply train loaded with 1,000 pounds of powder and 2,000 pounds of lead and laying siege to a Patriot outpost at Ninety Six. Denouncing the Tories as “robbers, murderers, and disturbers of peace and good order,” Patriot leaders demanded the return of the ammunition. In December 1775, under a muffled covering of 30 inches of snow, a detachment surprised the Tories’ camp and routed the king’s supporters. Once again, the Tories were forced to sign a document pledging not to take up arms against the Council of Safety.

“Allow Me in the Strongest Terms to Recommend That You Make Hostages of the Governor and the Officer”

The main focus of the Patriots’ opposition, however, was not the indigenous Tories, but the Crown’s legal representative in South Carolina, Governor Sir William Campbell. Drayton warned his fellow revolutionaries that “our situation is utterly precarious while the governor is at liberty. He animates these men, he tempts them, and although they are now recovered, yet their fidelity is precarious if he is at liberty to jog them again. Gentlemen, allow me in the strongest terms to recommend that you make hostages of the governor and the officer. To do this is not more dangerous than what we have done.” Burnfoot Brown hurried to Charleston to warn Campbell, but was arrested by the Council of Safety and ordered to leave the state. He eventually escaped to St. Augustine, Fla.

The Patriots stepped up their efforts to drive Campbell out of the state after two British sloops arrived in Charleston harbor. Cannon appeared on the waterfront where old warehouses had been. Patriots seized Fort Johnson, located southeast of the city on James Island. At the same time, a heavy battery went up across the water at Haddrell’s Point. And when a crew began to place guns at the mouth of the harbor on Sullivan’s Island, the British ships—with the last royal governor of South Carolina on board—abruptly sailed away.

King George III had been assured by the royal governors of his southern colonies that there were great numbers of Tories ready to flock to the king’s banner if the British Army exerted its presence in that region. In a report written before he took to sea, Campbell informed the monarch, “Let it not be entirely forgot that the king has dominions in this part of America. What defense can they make? Three regiments, a proper detachment of artillery, with a couple of good frigates, some small craft, and a bomb-ketch, would do the whole business here, and go a great way to reduce Georgia and North Carolina to a sense of their duty. Charleston is the fountain-head from whence all violence flows; stop that, and the rebellion in this part of the continent will soon be at an end.”

Believing that it would be a simple matter to capture the Southern port cities of Savannah and Charleston, the king earlier had ordered that a force equal to seven regiments be made ready to sail from Cork, Ireland. Admiral Sir Peter Parker was put in command of the fleet, while Lt. Gen. Sir Charles Cornwallis, then in England, was to command the expedition land forces. In preparation for the southern offensive, Maj. Gen. Sir William Howe, the British commander-in-chief in North America, appointed Maj. Gen. Henry Clinton to lead the so-called Southern Expedition. Clinton was to sail with 1,500 men in January and rendezvous with Cornwallis off the coast of Cape Fear, N.C. Here they would meet up with Loyalists who were marching toward the North Carolina coast. This combined force would then march into North Carolina and sweep south to Charleston “to support the Loyalists and restore the authority of the King’s government in the four southern provinces.”

Humiliating Defeat for the Highlanders

The grandiloquent plan quickly went awry at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, N.C., on February 27, 1776, when a Tory force of transplanted Scottish Highlanders was defeated by a much smaller force of rebel militia and summarily chased home. This defeat, like many the Scots had endured at the hands of the English in the old country, was accompanied by much beating of drums, wailing of bagpipes, and drawing of broadswords. In the end, however, it was two rebel cannon, nicknamed “Old Mother Covington and her daughter,” that turned the tide, blasting the Highlanders from the bridge and sending them cascading downward to drown in the 50-foot-wide creek. The humiliating defeat caused many of the Highlanders to take to the swamps for the next four years and dissuaded other Tories from turning out to meet the king’s regulars. When Clinton arrived at Cape Fear on March 12, he learned to his dismay—if not surprise—that the North Carolina loyalists had been soundly defeated.

The British fleet left Cork harbor in February, but a series of terrific storms dispersed the fleet and drove some ships back into the harbor. It was not until May 3 that Parker’s fleet entered Cape Fear River to rendezvous with Clinton. It was now too late to invade North Carolina and rescue the Highlanders, but Clinton’s orders gave him the option to proceed to either Virginia or South Carolina. If he went to South Carolina he was to capture Charleston as a prelude to the fall of Savannah.

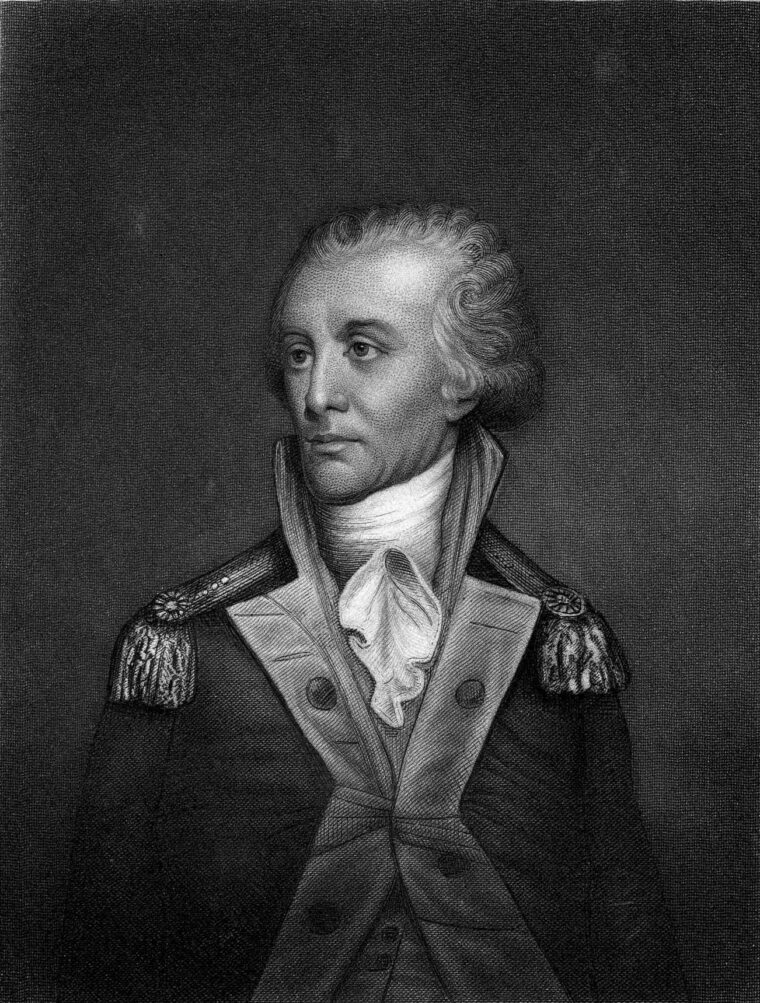

While the British were gathering their forces off the coast of North Carolina, in Charleston Patriot leader John Rutledge had returned from the Continental Congress bringing warnings of a British move in the South. He was elected president of the newly formed General Assembly, and under his leadership Charleston began to prepare for the British Army and Navy squadron known to be on the way. To strengthen the harbor’s defenses, mechanics and laborers were employed to fortify the town. Colonel William Moultrie, a wealthy plantation owner and veteran of the Cherokee War, was ordered to construct a fort on Sullivan’s Island, which at that time was only a wilderness covered with myrtle, live oak, and palmetto trees.

Sullivan’s Island was the key to the geographically shielded harbor. A large vessel sailing into Charleston first had to cross the Charleston Bar, a series of submerged sandbanks lying about eight miles southeast of the city. Half a dozen channels penetrated the bar, but only the southern pair could be navigated by deep-draft ships. A broad anchorage called Five Fathom Hole lay between the bar and Morris Island. A thousand yards north of that shoal loomed the crucial southern end of Sullivan’s Island.

By early March Moultrie began building a fort on Sullivan’s Island. From the beginning, the fortification was intended for seacoast defense. Its purpose was to make a seaborne invasion as costly as possible, or, better still, to prevent an invader from landing at all. Moultrie’s work gangs cut thousands of spongy palmetto logs and rafted them over from the other islands and the mainland. The fort took the shape of a rectangular wall 500 feet long and 16 feet wide, reinforced with sand to stop enemy shots. The workers constructed gun platforms out of two-inch planks and nailed them together with spikes. Since the garrison of such a structure could not reasonably be expected to annihilate the enemy, the fort was to be backed up by inland troops and a well-armed city.

Rutledge Sounded the Alarm, Shattering Charleston’s Peace

With North Carolina firmly in the hands of the Patriots, Clinton and Parker had to decide whether to attack Virginia by way of the Chesapeake Bay or Charleston by way of the harbor. While Clinton seemed to favor Virginia, Parker favored attacking Charleston. He sent the frigate Sphynx and the schooner Pensacola Packet to reconnoiter the approaches to Charleston, and the ships’ commanders returned with the news that the rebel fortifications on Sullivan’s Island were still unfinished and vulnerable to attack. That decided matters for the British leaders—Charleston would be attacked first.

Inside the city, residents learned that the English fleet and transports had arrived in Cape Fear River, and that it would only be a matter of time before the fleet sailed southward. After Sphynx and Pensacola PacketBristol, Experiment, Actaeon, Active, Solebay, Syren, Sphynx, Friendship, had openly reconnoitered the harbor, they grimly realized that the main fleet would soon arrive behind them. On May 30 the British fleet weighed anchor and headed south.

The peace of Charleston was shattered when Rutledge sounded the alarm. Taking courage, he concentrated his forces within the city and quickly constructed barricades at all the principal intersections and weak points where a British landing might be expected to occur. On May 31, Rutledge received news that the fleet lay anchored about 20 miles to the north of Charleston Bar. The next day the fleet appeared outside Charleston harbor. Assessing the situation, Clinton concluded that Sullivan’s Island was the key to Charleston’s defense and that its defeat would, in effect, subdue the city. Clinton worried that the surf at the island was too rough for an amphibious landing. Learning that Long Island, immediately north of Sullivan’s Island, was connected to the stronghold by a ford that could be traversed at low tide, Clinton ordered Cornwallis to lead an attack from the north. Without bothering to verify this intelligence, Cornwallis made plans to move his men onto Long Island.

“Old Danger” and “Swamp Fox”

On June 8, relying on impressed pilots to navigate the bar surrounding the harbor, Parker ordered his ships to move to anchorage. After sounding the channels and making other preparations, the smaller ships and warships began their move to anchorage at Five Fathom Hole, a 30-foot-deep ravine out of range of Fort Sullivan. Meanwhile, the Patriots inside Charleston sent out frantic calls for assistance from the hardy frontiersmen of the backcountry and the wilderness beyond. The response was immediate. Lt. Col. William Thompson, a veteran Indian fighter nicknamed “Old Danger,” brought the 300-man-strong 3rd Regiment of Rangers into the city, while minister-turned-fighter John Peter Muhlenberg led a contingent south from Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Also coming to Charleston’s aid was the 2nd South Carolina Rifle Regiment, led by Lt. Col. Thomas Sumter and featuring a man who would later become famous in his own right as a guerrilla leader of unrivaled valor—Major Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox.”

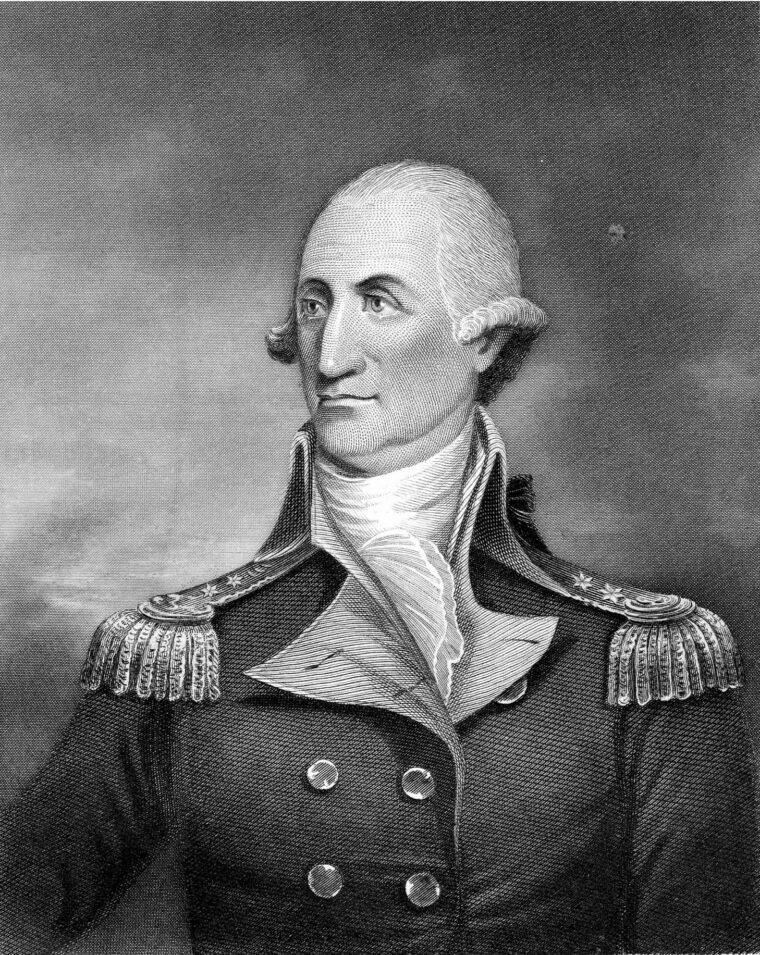

In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress sent Maj. Gen. Charles Lee, commander of the Southern Department, to lead the newly arriving land forces. Lee, a native-born Englishman who had fought in the French and Indian War, in Portugal, and with the Russians against the Turks, had a reputation as a brave and experienced officer, although he was admittedly rough in his manners and quite outspoken. (His sharp tongue would later cause him to quarrel openly with General George Washington at the Battle of Monmouth, leading to his court-martial and dismissal from the army.)

Every day Lee would travel throughout the area reviewing the preparations being made and issuing orders to throw up military works at various places. Once, coming across a battery that had been planned and sited by William Henry Drayton, Lee exclaimed, “What damned fool planned this battery?” Told that it was Drayton, a chief justice in South Carolina at the time, Lee refused to back down. “He might be a very good chief justice,” he said of Drayton, “but he is a damned bad engineer.” Drayton would repay the insult in spades when, as a congressman, he voted to confirm Lee’s court-martial and dismissal from the service.

On June 9, Lee examined the fortifications on Sullivan’s Island and found them severely lacking. He advised Rutledge that he did not like the post, that it could not hold out half an hour, that there was no way to retreat, and that it was nothing better than a “slaughter pen.” The garrison, he said, would be sacrificed needlessly. Rutledge refused to accept Lee’s pessimistic judgment of the conditions on Sullivan’s Island, and he wrote Moultrie at the fort, “General Lee wishes you to evacuate the fort. You will not without an order from me. I will sooner cut off my hand than write one.”

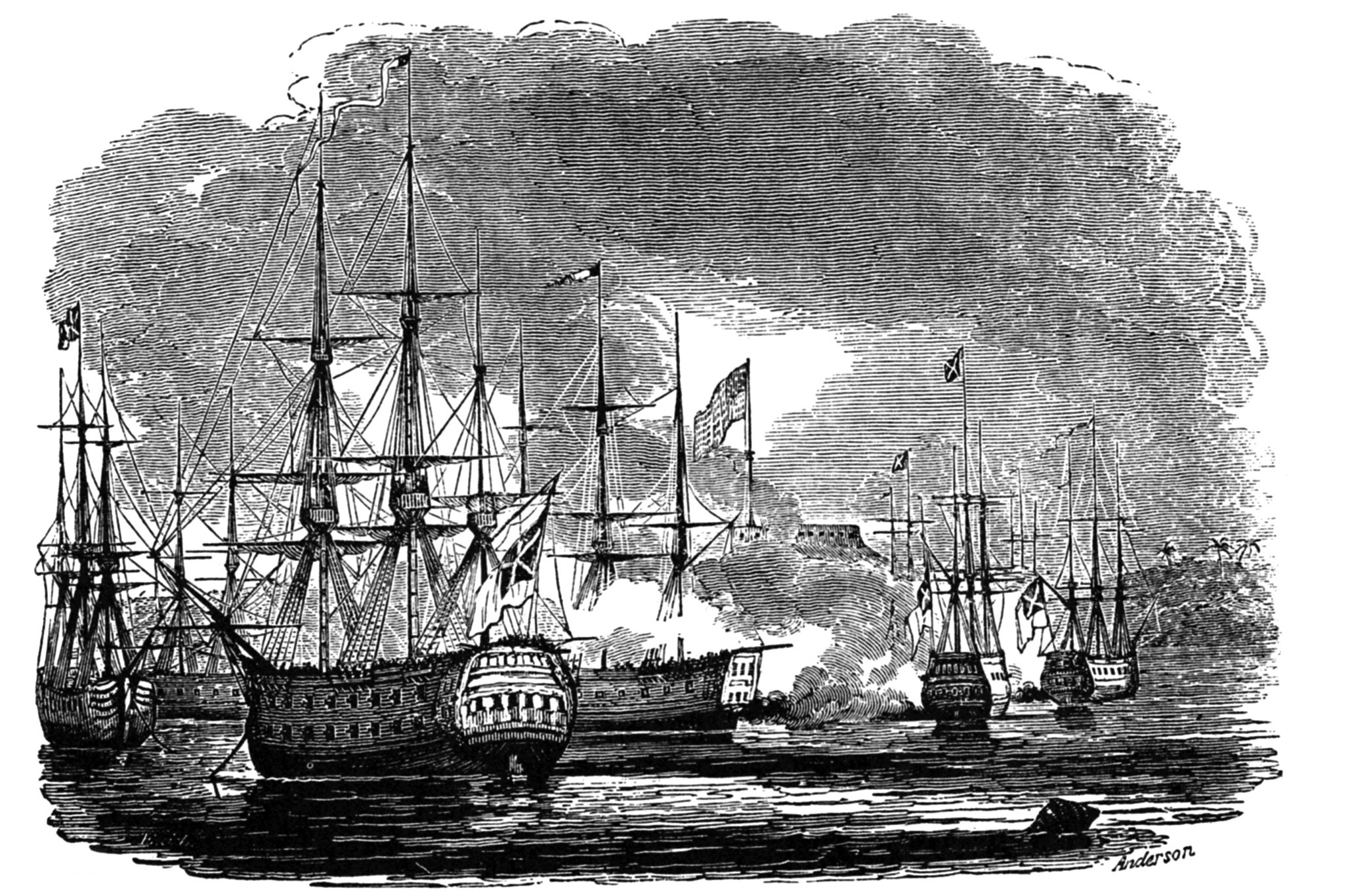

The defense of Charleston depended on an incomplete fort made of palmetto walls, 16 feet wide and filled with sand, rising 10 feet above a wooden platform, on which soldiers and cannon stood. There was also a hastily erected palisade of thick planks that helped guard the powder magazine and the unfinished northern wall. Dotting the breastworks, the southeast and southwest walls, and the corner bastions were an assortment of cannon, ranging from 9- and 12-pounders to English 18-pounders and French 26-pounders. Arrayed against this fortification were the vessels of Parker’s experienced fleet, including transports, supply vessels, service vessels, and nine men-of-war Bristol, Experiment, Actaeon, Active, Solebay, Syren, Sphynx, Friendship, and the bomb-vessel Thunder—together mounting 260 heavy guns.

On June 9, Clinton landed an amphibious force of 500 soldiers on Long Island. Once again Lee proposed to Rutledge that all forces be withdrawn from Sullivan’s Island, and once again Rutledge refused. Moultrie carefully evaluated both the dangers and his resources and prepared to repel an attack by sea or land. At the same time, he had to fend off Lee’s less than inspiring advice. “General Lee’s whole thoughts,” said Moultrie, “were taken up with the post on Sullivan’s Island; all his letters to me show how anxious he was at not having a bridge for a retreat; for my part I never was uneasy on not having a retreat because I never imagined that the enemy could force me to that necessity; I always considered myself as able to defend that post against the enemy.” Not entirely convinced, Lee removed half of Moultrie’s supply of 10,000 pounds of gunpowder.

On June 10, Parker’s 50-gun flagship, Bristol, and the last of his deep-draft transports crossed Charleston Bar and dropped anchor at Five Fathom Hole alongside the rest of the fleet. The movement did not go unnoticed in the city. The British were now in position to launch their attack, and the people of Charleston manned the barricades and entrenchments.

Clinton Plans to Attack by Land (and by Sea)

On the 15th, Parker instructed his squadron, and the next day he informed Clinton of his attack plans. After much delay, Cornwallis’s brigade was transported to the island on June 20. It was only then that they finally realized that the information they had been operating under was faulty. Clinton had planned to launch a land assault across Breach Inlet, between Long Island and Sullivan’s Island, and attack the fort from its unfinished rear while Parker’s ships assaulted it from the sea. The depth of the Breach at ebb tide, however, which first had been reported to be only half-a-yard, was in reality seven feet—too deep for infantry to safely wade ashore. Compelled to change his strategy, Clinton also changed the date of attack to the June 23 and started making plans to ferry his troops across the inlet. Meanwhile, Parker’s ships were to penetrate the harbor, level the fort, and support Clinton’s amphibious assault.

Both the British and Patriot forces were as ready as they could reasonably hope to be. Lee, while choosing to remain in the city, continued to correspond with Moultrie several times daily. Moultrie’s men continued working on the defenses of the fort, while Colonel William Thomson and his men continued preparing a formidable position to defend the island’s north end. However, it was not until June 27, when the 50-gun Experiment crossed the Charleston Bar and joined Parker’s fleet, that the British were finally ready to launch an attack. Everything pointed toward the 28th as the fateful day.

As a gentle sea breeze skimmed across the harbor on the morning of the 28th, Moultrie rode out to confer with the commander of his advance guard, Colonel Thomson. Thomson had posted 50 members of the militia behind sand hills and myrtle bushes. A few hundred yards in the rear, breastworks had been thrown up and manned by 300 riflemen from his own Orangeburg Regiment, 200 from Clark’s North Carolina Regiment, 200 more of the men of South Carolina under Captain Daniel Horry, and a company of riflemen. On his left he was protected by a morass; on his right by one 18-pounder and one brass 6-pounder, which overlooked the spot where Clinton would wish to land.

Observing heavy activity along the beach at Long Island and the topsails being loosened on the British men-of-war, Moultrie hurried back to the fort. He rapidly ordered all 435 men under his command to their posts. The Patriots had 31 cannon on hand in the fort, but no more than 21 could brought into use at the same time, and there were only 28 rounds of ammunition. At Haddrell’s Point, across the bay, Maj. Gen. John Armstrong had about 1,500 men. The first regular South Carolina Regiment, under Christopher Gadsden, occupied Fort Johnson, which stood on the most northerly part of James Island, about three miles from Charleston, and within point-blank range of the channel. In all, the city was protected by more than 2,000 men.

Prelude to Battle

Parker signaled the fleet to make ready to attack at 9 am, and an hour later his ships began maneuvering into firing position. Thunder and Friendship were anchored one and a half miles from the fort, covered by the 28-gun Friendship; Thunder’s own gunners began the battle by lofting 13-inch mortar rounds toward the fort. When the shots fell short, the principal engineer immediately increased the quantity of powder added to each mortar. The massive recoils loosened the ship’s planks, totally disabling the vessel for the rest of the day. She retired ingloriously from the fight, having wounded one Patriot and killed, it was said, “three ducks, two geese, and one turkey.”

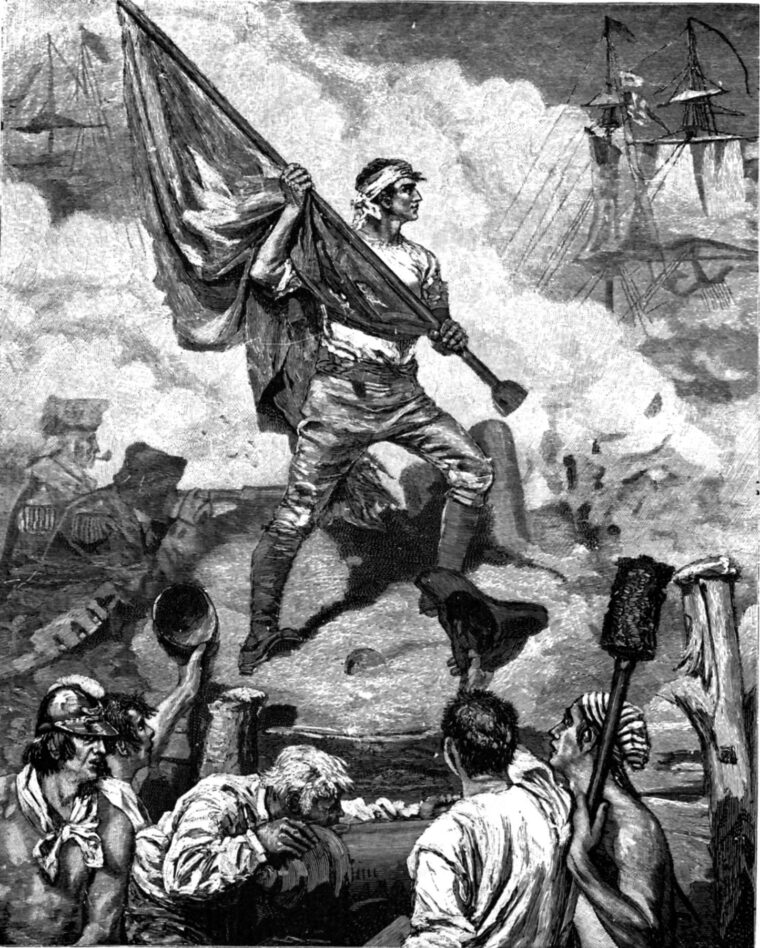

At about 10:45, four other men-of-war— Active, Bristol, Experiment, and Solebay—took up positions about 400 yards out in a line directly opposite most of the fort’s cannon, and began an intense barrage. The British moved slowly and confidently, fueling the fears of Charlestonians. Inside the fort, gun crews labored furiously to return the British fire. The Patriots quickly abandoned three poorly protected 12-pounders west of the fort, but the main walls of sand and spongy palmetto wood stood up well and smothered most of the British bombs before they could explode. Those that fell inside the fort landed in the marshy center, where the open morass swallowed them up. By the end of the day, the walls would actually be stronger, having absorbed enough shells to buttress their original design.

Exposed to the incessant bombardment, Moultrie’s men stuck to their guns. Forced to reserve their power, the gun crews fired very slowly, with each gun commander waiting for the smoke to clear before taking careful aim. This precision first made itself felt aboard the Active, which early on sustained four or five hits. Meanwhile, Clinton weakly supported the naval attack by first directing his batteries on Long Island to open fire on Thomson’s position. Thomson quickly returned the fire, but the exchanges on both sides were ineffectual.

With floating batteries and armed craft dispersed to cover the landing, Clinton ordered the light infantry, grenadiers, and the 15th Regiment into their boats. The detachment had scarcely left Long Island before Thomson’s skillful sharpshooters began raining down a devastating torrent of fire. A local Tory who had joined the British force in total violation of the Treaty of Ninety Six, recalled that “it was impossible for any set of men to sustain so destructive a fire as the Americans poured in on this occasion.” Realizing any further attempt to effect a landing would only lead to the loss of many men without any possibility of success, Clinton called off the operation. Now without a plan of action, he and his men sat on the sidelines, plagued by a patriotic swarm of Charleston mosquitoes, and watched as the naval battle unfolded around them.

“One of the Most Furious and Incessant Fires I Ever Saw or Heard”

Taking advantage of the covering fire, Parker’s 28-gun frigates Syren and Actaeon and the 20-gun Sphynx attempted to move in closer for enfilading fire and to cut off any Patriot retreat. But the pilots, being unfamiliar with the harbor, soon ran all three ships onto a sandbank, known locally as Lower Middle Ground. The British continued their bombardment to little effect as the palmetto logs possessed an elastic quality that was highly effective in warding off cannonfire. However, by mid-afternoon the British had been able to refloat Sphynx and Syren, although Actaeon remained aground. The two vessels rejoined the fleet in a general bombardment of the fort.

The sea shimmered from the glare of a cloudless sky as Moultrie ordered his gun captains to concentrate their fire on the Bristol and Experiment. With a slow and skillful fire, the Patriot gun crews began inflicting heavy damage aboard these men-of-war. On board Bristol, Admiral Parker’s flagship, every person on the quarterdeck was killed or wounded. Lord Campbell, South Carolina’s royal governor, manning a gun on the ship, was wounded by a wooden splinter, a wound that would eventually cause his death two years later. Parker was also wounded—somewhat ignominiously—by a splinter that tore off his pants and “left his posteriors quite bare.” Another splinter pierced his knee and left him unable to walk without aid. The ship’s captain, John Morris, underwent a shipboard amputation of his arm and died a few days later.

During the artillery duel, which he called “one of the most furious and incessant fires I ever saw or heard,” General Lee visited the fort briefly. No longer convinced that the defense was a fool’s errand, he graciously conceded, “Colonel, I see you are doing very well here. You have no occasion for me. I will go up to town again.” Moultrie, enormously gratified by his men’s performance, helped carry buckets of grog to the gunners on the firing platforms. “I never had a more agreeable draught than what I took out of one of those buckets,” he recalled later. “It may be very easily conceived what heat and thirst a man must feel in this climate upon a platform on the twenty-eighth o June, amidst twenty or thirty heavy pieces of cannon in one continual blaze and roar and clouds of smoke curling over his head for hours together. It was a very honorable situation, but a very unpleasant one.”

23 Dead, 56 Wounded

At 4 pm an additional 500 pounds of powder was sent over to Sullivan’s Island by Acting Governor Rutledge, who advised, “Do not make too free with your cannon. Cool and do mischief.” With the extra powder, the defenders continued hurling theirs shot into the British ships with deadly accuracy. As an evening sea breeze swept over the harbor, 40 men lay dead and 71 wounded on board Bristol alone. The ship had suffered 70 hits, with extensive damage to her hull, yards, and rigging. On board Experiment, 23 were dead and 56 wounded. Active and Solebay both had 15 casualties. The wounded and embarrassed admiral had had enough. At 9 pm he broke off the battle, and two and half hours later the British ships withdrew to Five Fathom Hole.

After a long day of fighting, the British fleet had been unable to penetrate Charleston harbor’s defenses, giving the American Patriots a stunning victory at the comparatively low cost of 11 killed and 26 wounded. The British still had a major problem. Of the three ships that had run aground, Actaeon was still unable to extract herself, despite the best efforts of her crew. The captain requested Parker’s permission to abandon ship and destroy her to keep the ship from falling into the hands of the rebels. On the morning of June 29, the British set the grounded Actaeon afire and abandoned her to her fate. A Patriot salvage party went out to the ship after she was abandoned and was able to gather the ship’s bell, the colors, and various stores before the spreading fire endangered their safety. Half an hour later, the ship’s magazine exploded. The Battle of Sullivan’s Island had required only a single day to play itself out.

The engagement at Sullivan’s Island was one of unquestioned importance. Coming within six days of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, it stood as a symbol of the American capacity to successfully oppose the mighty British at arms. The thwarting of the British offensive in the South helped win uncommitted Americans to the struggle for independence. It also dispelled the idea of British superiority and drove many loyalists into hiding for the duration of the war. Temporarily, the triumph forestalled another serious British assault against the South, enabling the Southern colonies to support vital campaigns in the North. For South Carolina, it produced a confidence in the government led by John Rutledge and forestalled another British effort to take Charleston for over three years.

The news from Charleston was met with great rejoicing throughout the colonies. Following directly on the heels of the victory at Moore’s Creek Bridge and the British evacuation of Boston, the daring feat against all odds fired the imagination of its citizens. Here was the model for future triumphs. In a daylong battle with the best the British Navy had to offer, a gallant and spirited band of Patriots had defeated an overwhelming naval and military force, and after whipping them, drove them entirely from their shores. General Lee spoke for many when he declared, “The behavior of the garrison, both men and officers, with Colonel Moultrie at their head, I confess astonished me.” A British surgeon who took part in the battle was no less amazed. “This will not be believed when it is first reported in England,” he said. “I can scarcely believe what I myself saw that day… one of the most distressing of my life.”

A New War Song

For the British, the defeat was humiliating. It was another instance that demonstrated the British lack of understanding of the resolve of the Patriots, their inability to put together a unified plan, or muster their superior resources in a timely manner. A superb naval flotilla and army had been thwarted, in large degree, by imprudent mistakes made by veteran officers. Poor planning and the refusal of the army and navy to cooperate sealed the doom of the British. The British lost all element of surprise and failed to take advantage of American weakness in early June. There were no naval officers in the fleet familiar with Charleston Harbor. Instead Parker relied on impressed pilots to guide the ships to their crucial anchorage. The folly was incredible and became the target of vicious satire. In “A New War Song,” ascribed to Sir Peter Parker, the admiral concludes:

Now bold as a Turk

I proceed to New York

Where with Clinton and Howe you may find me.

I’ve the wind in my tail,

And am hoisting my sail,

To leave Sullivan’s Island behind me.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments