By Mike Phifer

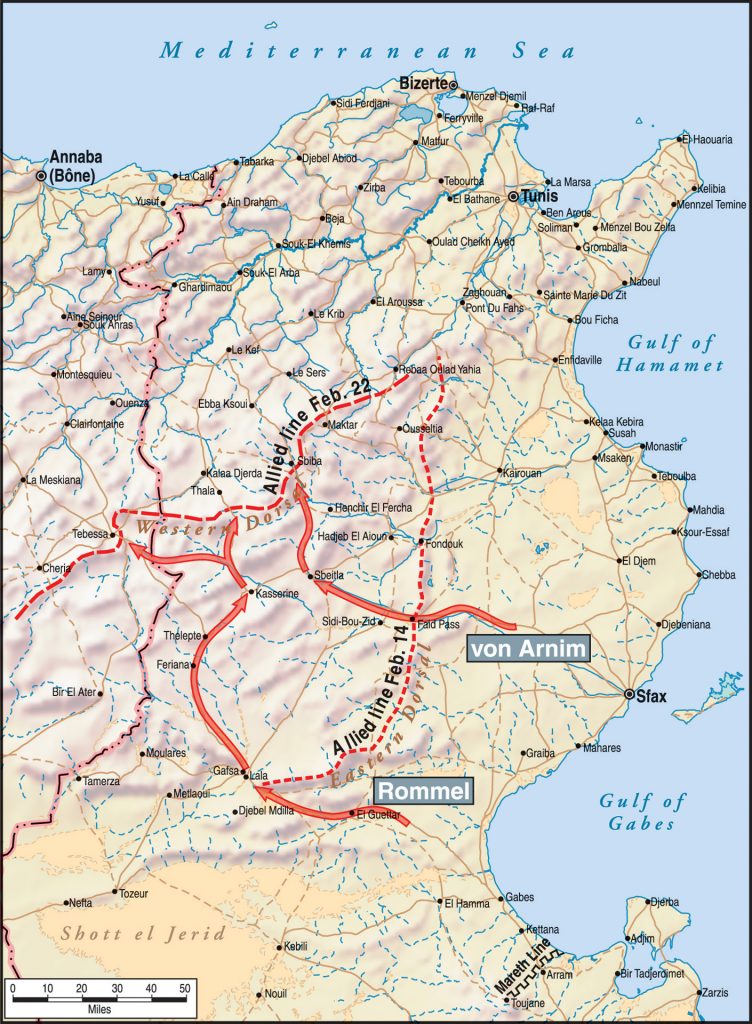

Ignoring the swirling sands stirred up by the fierce winds of the Sahara Desert in the early morning hours of February 14, 1943, Generalleutnant Heinz Ziegler ordered his panzer columns forward to attack the American forces deployed in central Tunisia. More than 100 tanks and halftracks and trucks packed with infantry rumbled through the Faid Pass in the Eastern Dorsal of the Atlas Mountains. The first objective of his two powerful panzer columns was to strike at a pair of prominent hills, known locally as djebels, 10 miles apart that bracketed the strategic crossroads of Sidi bou Zid. Between the two hills ran Highway 13 from Faid to Sebeitla. From there Rommel’s panzers would head toward the Kasserine Pass.

Just as the sun hazily began to rise above the mountains, the tanks and vehicles of the 10th Panzer Division rolled out onto the flatland.

Generalmajor Friedrich Freiherr von Broich’s 10th Panzer headed for Djebel Lessouda. Meanwhile, Colonel Hans Georg Hildebrandt’s 21st Panzer Division debouched from the Mazil Pass bound for Djebel Ksaira, 10 miles south of Djebel Lessouda. American forces holding Sidi bou Zid remained unaware of the German forces bearing down on them.

The vanguard of the 10th Panzer Division sped past the village of Faid and continued westward. The panzers in the vanguard overran a squad of American troops a few miles west of Faid so fast that the Americans had no opportunity to use their radio or even fire a signal rocket as a warning. The panzer troops took the crews of 10 American tanks by surprise while they were cooking their breakfast and knocked out six tanks in short order. When more American tanks advanced in a vain effort to stem the panzer onslaught, the crack German panzer troops destroyed six more American tanks.

A few miles further, von Broich’s column split into three Kampfgruppen, or battle groups. One of these moved around Djebel Lessouda; its mission was to knock out American artillery and encircle the hill. The other two battle groups moved south to envelop Sidi bou Zid.

The American forces defending Djebel Lessouda consisted of the 2nd Battalion/168th Infantry Regiment of the 34th Infantry Division, a company of tanks, and a platoon of tank destroyers. Lt. Col. John Waters, the executive officer of the 1st U.S. Armored Regiment, led the task force. The 900 American troops holding this hill, as well the 1,700 men under Colonel Thomas Drake at Djebel Ksaira, would soon find themselves overrun by the German panzer spearheads.

The Battle of Sidi Bou Zid was the opening clash by Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel’s German-Italian Panzer Army against Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredendall’s 32,000-strong U.S. II Corps advancing into central Tunisia. It would be all that Cols. Waters and Drake could do just to hang on until help arrived; that is, if it ever did.

The Allies had begun Operation Torch, their invasion of Vichy French North Africa, on November 8, 1942. American and British troops in three task forces had stormed the coasts of both Morocco and Algeria. The Vichy troops offered some token resistance, but two days later General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force of the North African Theater of Operations, brokered a ceasefire. French forces in the two countries promptly switched over to the Allies.

The purpose of Operation Torch was to maintain pressure on the Germans until landings in France could be made. British Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery’s Eighth Army had inflicted a serious defeat in autumn 1943 on German and Italian forces at the Second Battle of El Alamein in Egypt. As a result, Rommel’s Panzer Army Afrika was in full retreat west across Libya with the British Eighth Army in slow pursuit. The Allies intended to crush Panzer Army Africa between armies converging on Tunisia from both the east and west.

The Allies eastern thrust began on November 14, when Lt. Gen. Kenneth Anderson’s British 1st Army struck out from Algeria bound for the Mediterranean ports of Tunis and Bizerte in Tunisia. Anderson commanded the British V Corps, French XIX Corps, and U.S. II Corps.

The Germans quickly sent reinforcements by air and sea from Italy to secure a bridgehead in northeastern Tunisia and forestall the British and American advance on Tunis. Generaloberst Hans-Jurgen von Arnim arrived on December 9 at the Tunisian bridgehead to take command of the newly created 5th Panzer Army. Ziegler, who was Arnim’s deputy, accompanied him. Sporadic fighting occurred down the length of the battlefront in central Tunisia, but it eventually subsided as supply problems and bad weather forestalled fresh British and American attacks. Winter rains, which typically lasted several months, had arrived in January on the Tunisian coastline. Eisenhower realized that because of the bad weather, large-scale operations by the British First Army on the North African coast would have to wait until the soil dried in the spring.

Rommel’s chief concern was that the Allies would capture Gabes on the Tunisian coast and drive a wedge between the Axis armies. He therefore began, on January 2, 1943, to withdraw his forces from Libya, instructing his subordinate commanders to redeploy to the Mareth Line, a system of fortifications built in the previous decade by France in southern Tunisia. Although the line was originally intended to protect French-held Tunisia against an Italian invasion from its colony in Libya, it would now protect the Germans from the British.

By late January, Rommel’s German-Italian Panzer Army consisted of 30,000 German and 48,000 Italian troops. In contrast, Arnim’s better-supplied 5th Panzer Army comprised 74,000 German and 26,000 Italian troops. Arnim’s army was further strengthened by the 21st Panzer Division, which Rommel had sent to reinforce Arnim.

As for the Allies, they were deployed in late January on a 250-mile-long front in central Tunisia across the eastern and western Dorsals. The two mountain ranges stretched south across central Tunisia like an inverted V. The Eastern Dorsal curves to the southwest and terminates near Gafsa, while the Western (or Grand) Dorsal runs from the northeast to the southwest ending near the Algerian border. The eastern range has key mountain passes at Faid, Fondouk, and Pichon, while the western range had key passes at Sbiba and Kasserine.

Lt. Gen. Charles Walter Allfrey’s British V Corps held the northern section of the Allied line, General Alphonse Juin’s French XIX Corps held the middle section, and Maj. Gen. Lloyd Fredendall’s U.S. II Corps held the southern section. Fredendall’s corps was composed of Maj. Gen. Orlando Ward’s 1st Armored Division and elements of the 1st and 34th Infantry Divisions.

“Old Ironsides,” as the 1st Armored Division was known, consisted of Combat Commands A, B, and C. These combined-arms task forces, much like the German kampfgruppen, consisted of tanks, tank destroyers, infantry, artillery, and engineers. Since the arrival of the 1st Armored Division in North Africa, only CCB had seen combat.

Arnim dispatched a battle group on January 18 to attack French forces in the Ousseltia Valley in central Tunisia. With a force consisting of Tiger tanks and 5,000 infantry, the Germans overran French positions and seized the passes of Pichon and Fondouk. The French appealed directly to Eisenhower for aid, and he instructed Fredendall to send a relief force. The task of relieving the French fell to Brig. Gen. Paul Robinett, the commander of the 1st Armored Division’s CCB. In the subsequent fighting, the Germans mauled the French, inflicting 3,500 casualties.

In the early morning of January 24, Colonel Robert Stack’s CCC raided Sened Station on Highway 14 between Gafsa and Maknassy. The Americans inflicted 100 casualties on its Italian garrison and captured 96 prisoners. The raid was intended as a preliminary move toward a future attack against Maknassy.

Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring was responsible for all operations in the Mediterranean basin. Kesselring instructed Arnim to capture Faid Pass and then to drive towards the American supply base at Tebessa on the Algerian-Tunisian frontier, but Arnim did not believe he had enough supplies for such an operation. For that reason, he limited the attack, which was launched on January 30. He issued orders to the 21st Panzer Division to seize Faid Pass but did not instruct them to continue westward. The German panzer formations easily overwhelmed the French troops and seized control of the pass.

Once again, the French requested immediate relief from Fredendall. From his underground bunker complex in Speedy Valley, located nine miles southeast of Tebessa, Fredendall forwarded the request to Lt. Gen. Anderson. Anderson instructed him at mid-morning to immediately move to the relief of the French and to retake Faid pass.

Fredendall in turn ordered Colonel Raymond McQuillin, the commander of the 1st Armored Division’s CCA, to assist the French. However, the orders McQuillin received instructed him not to weaken the defense of Sbeitla, which was situated 30 miles west of the Faid Pass. As McQuillin’s relief force set off for Faid Pass on January 30, it was caught in the open not only by German Stukas but also by Allied aircraft that mistook it for an Axis column. McQuillin halted his bloodied troops seven miles from the pass.

After regrouping, McQuillin attacked Faid Pass on January 31. The Germans had moved quickly to fortify the pass by deploying their formidable 88mm anti-aircraft guns as anti-tank weapons along with machine guns and mortars. German 88s knocked out nine Sherman tanks. Another assault the following day also fizzled out. To make matters worse, the German 10th Division succeeded the same day in capturing Pichon Pass to the north, and a subsequent raid by the 1st Armored Division’s CCD on Maknassy to the south also ended in failure.

Although Rommel had been ordered to return to Germany to recover from exhaustion, he decided to remain in North Africa. He did this because he saw an opportunity to punch through American forces on the eastern and western dorsals and capture the American ammunition depot at Tebessa. Leaving a small force to hold the Mareth Line, Rommel calculated that the Germans had two weeks to smash the American forces in Tunisia. Once he had pummelled the Americans, Rommel intended to turn his attention back to the British Eighth Army. While Rommel dealt with the Eighth Army, Arnim could strike the British in northwestern Tunisia.

Kesselring met with Rommel and Arnim on February 9 to discuss strategy. The result was the creation of a coordinated operation against the Americans. In the first thrust, Operation Fruhlingswind (Spring Wind), Arnim’s 5th Panzer Army would debouch from Faid Pass on February 14 with the goal of annihilating McQuillin’s CCA at Sidi bou Zid. In the second thrust, Rommel would launch Operation Morgenluft (Morning Air) two days later with the goal of capturing Gafsa. Rommel intended to loan Arnim the 21st Panzer with the understanding that it would be returned in time for the second phase of Rommel’s operation, which would be a strike through Kasserine Pass in the Grand Dorsal to capture Tebessa. “We are going to go all-out for the total destruction of the Americans,” Kesselring told his subordinates.

Eisenhower arrived at II Corps headquarters in Speedy Valley on February 13 to meet with Fredendall and Anderson. Colonel Benjamin A. Dickinson, who was Fredendall’s G-2 (intelligence officer), informed Anderson that the Germans were likely to launch an attack through Faid or Gafsa. Anderson dismissed the warning, believing instead that the Germans were planning an attack through Fondouk Pass in an effort to outflank the British V Corps in northern Tunisia.

Anderson left the meeting when it was reported that a German attack was imminent in the north. Eisenhower then headed out on tour of the American lines. At Sidi bou Zid, Colonel Peter Hains, commander of the 1st Armored Regiment, was unhappy with the placement of CCA nearby and let Eisenhower know. Other senior officers had made similar complaints to Ike. “Get your mine fields out first thing in the morning,” Eisenhower ordered before returning to II Corps headquarters.

Earlier on February 11, Fredendall had ordered that Djebel Lessouda and Djebel Ksaira be strongly held, as he believed they were critical to the defense of Faid. Fredendall further ordered the establishment of a mobile reserve near Sidi bou Zid. For his part, though, Hains believed the hills were too far apart to allow the troops defending them to support each other. Furthermore, he believed that something was afoot with the Germans defending Faid Pass.

The sandstorm that masked Generalleutnant Ziegler’s attack on the morning of February 14 began to abate by mid-morning. This allowed Col. Waters, the Task-Force leader, to see the full extent of the 10th Panzer’s assault on Djebel Lessouda; it was only then that Waters learned that the Germans had overrun CCA’s forward outposts.

McQuillin ordered Lt. Col. Louis Hightower to counterattack the Germans around Djebel Lessouda. With that goal in mind, Hightower led companies H and I of the 1st Armored Regiment and 12 tank destroyers from 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion out of Sidi bou Zid to engage the Germans. The tank clashes between the American and German armored forces included M3A1 Stuart light tanks, M3A3 Lee medium tanks, and M-4 Sherman medium tanks pitted against Panzer IV medium tanks and Panzer VI Tiger heavy tanks.

Stukas with sirens shrieking swooped down on Hightower’s armored column. They did little damage, but Hightower’s force soon came under fire from the German panzers. With a number of his Shermans knocked out and burning, Hightower conducted a fighting withdrawal back to Sidi bou Zid. Waters’ task-force troops on Djebel Lessouda would have to fend for themselves.

The situation worsened for the Americans as the 21st Panzer Division advanced northwards from Maizila Pass, 20 miles to the south. While one battle group encircled Col. Drake’s 1,700-srong troop command, another assaulted Sidi bou Zid. The Germans were executing a carefully planned double-envelopment of McQuillin’s 1st Armored’s CCA: The 10th Panzer formed one pincer, and the 21st Panzer the other.

Most of the American troops were in full flight from the Germans by late morning. All manner of vehicles raced west along Highway 13. At the intersection of Highways 3 and 13, Lt. Col. William Kern set up a blocking position with a company of light tanks and armored infantry; the intersection became known as Kern’s Crossroads.

By 12:40 pm McQuillin had withdrawn from Sidi bou Zid and set up a new command post five miles west of the village. In the meantime, Hightower’s Shermans attempted to cover the retreating American forces but ultimately succumbed to the German blitz.

Hightower’s tank knocked out four German tanks before it was hit and set ablaze. Hightower and his crew managed to climb from the burning Sherman and stumble west for Kern’s Crossroads.

By this time, Col. Drake had shifted his command post to Garet Hadid, a more defensive position on high ground four miles west of Djebel Ksaira. He took with him 650 infantry and support troops. Approximately 1,000 troops of the 3rd Battalion, 168th Infantry of the 34th Division, commanded by Lt. Col. John Van Vliet, remained on Djebel Ksaira. Lt. Col. Robert Moore’s 2nd Battalion continued to hold out on the upper slope of Djebel Lessouda.

Col. Drake requested permission from McQuillin to withdraw west; McQuillin forwarded the request to Fredendall, who denied it. Drake then wrote a message to Ward stating that his command was in dire straits and needed immediate assistance. The colonel gave the message to Lieutenant Marvin Williams, who roared off in a jeep to find Ward at Sbeitla.

Williams reached Ward’s command post at Sbeitla and delivered Drake’s message. Ward told the young officer that a counterattack was being planned. Ward had requested reinforcement from CCB, which was deployed near Maktar, but Lt. Gen. Anderson intervened in the matter. Believing that the assault on Sidi bou Zid was a diversion and that the Germans’ real objective was Fondouk Pass, Anderson allowed only the 2nd Battalion of the CCB, led by Lt. Col. James Algers, to proceed to Sbeitla. The Germans captured Ward at 4:00 pm.

An hour later the two panzer divisions made contact west of Sidi bou Zid. The nine German battalions participating in the attack against McQuillin’s CCA had destroyed or captured 44 American tanks, 59 half-tracks, and 29 artillery pieces. Concerned about the possibility of an American counterattack to relieve the remaining U.S. forces in the sector, Generalleutnant Ziegler halted for the night.

Angered over Ziegler’s caution, Rommel urged Arnim to order his deputy commander to press his attack against Sbeitla. Despite Rommel’s earnest request, Arnim concurred with Ziegler, favoring instead a push north towards Pichon and Fondouk passes.

As a precaution against a German attack on the Allies’ southern flank, Anderson ordered the evacuation of French and American troops from Gafsa. The Allied troops proceeded to destroy bridges and other infrastructure before withdrawing west towards Feriana on heavily congested roads.

On February 15, Col. Stack’s CCC launched a counterattack to relieve American forces on Djebel Ksaira. Sherman tanks arrayed in a V formation spearheaded the attack while tank destroyers from the 701st Tank Destroyer Battalion covered their flanks. Two batteries of self-propelled artillery, as well as soldiers of the 3rd Battalion, 6th Armored Regiment, followed the armor. The Americans had failed to reconnoiter the German positions, though, and were in for an unpleasant surprise: The Germans in their path were much stronger than they had anticipated.

The Germans allowed Stack’s first wave of tanks to pass by their hidden antitank guns before opening up on the Shermans. Panzers from the 10th and 21st Panzer Divisions then swept around the Americans in a bid to cut them off.

The Germans badly savaged Algers’ forces; in the confused fighting, the Germans captured Algers himself. The result of the action was that the two U.S. infantry battalions remained marooned on Djebel Lessouda and Djebel Ksaira.

Despite their tactical successes, much dissension remained among the senior German commanders. Rommel was vexed by the slowness exhibited by Generaloberst Arnim and Generalleutnant Ziegler. Rather than exploit his local victories, Arnim dispatched patrols toward Kern’s Crossroads to see if the Americans were planning another counterattack. When Kesselring learned on February 16 of the situation on the ground, he ordered Arnim to take Sbeitla.

On the night of February 15-16, a P-40 Warhawk flew over Djebel Lessouda. Its pilot dropped a sack containing orders that the Americans withdraw from the hill. After spiking their heavy weapons and destroying their vehicles, Lt. Col. Moore marched his troops off the hill in two files under cover of darkness on a moonless night.

All did not go well, though. A German sentry challenged them, and then a machine-gun team opened fire on them. “Scatter! Run like hell!” shouted Moore. Mortar rounds began to burst around them as the Americans fled for their lives. Moore had no choice but to leave the wounded behind with Chaplain Eugene Daniel. Moore’s troops trickled into American lines throughout the following day. Of his initial force, fewer than half made it to safety.

As bad as things were for Moore’s retreating troops, matters were even worse for Drake’s force on Garet Hadid and Lt. Col. Van Vliet’s troops on Djebel Ksaira. They did not receive permission to fight their way through German lines until the afternoon of February 16. Like Moore’s command, they destroyed their equipment and marched down from the hills under cover of darkness.

The Germans overtook Col. Thomas Drake’s retreating column the following morning west of Sidi bou Zid. The colonel succeeded in rallying 400 men, and although they held off the Germans for an hour, they ultimately surrendered in the face of superior forces. At that point, CCA had lost a total of two tank and two infantry battalions. The Americans withdrew their remaining forces from Kern’s Crossroads on February 17. The survivors established a new position at Sbeitla bolstered by Robinett’s CCB.

With German forces probing the American defenses on the eastern side of Sbeitla, McQuillin relocated his command post to the west side of town. At the same time, American engineers began to blow up the ammunition dump, water-pumping station, and a railroad bridge at Sbeitla. Rumors quickly circulated among the battle-weary troops that the Germans had overrun CCA, and panic began to spread. Some of the troops in Sbeitla fled west without orders.

Anderson finally realized, two days into the battle, that the Americans were facing the German main force. He issued orders for the Americans to forgo further counterattacks. He also issued orders for the Americans to evacuate Sbeitla and withdraw through the Kasserine Pass towards Thala. To buy time for those troops already retreating from the town to make good their escape, elements of Combat Commands A and B fought desperate rearguard actions.

The Germans renewed their attack on Sbeitla on February 17, focusing on the south side of town, which was held by the CCB. Gen. Fredendall had issued orders to Ward not to withdraw from the town before midday. Ward deployed the surviving American armor and tank destroyers in a cordon around the town to hold the Germans at bay.

German panzers traded fire with American armor. A battalion of tank destroyers stationed on Brig. Gen. Robinett’s northern flank retreated into Sbeitla. Chaos reigned inside the town, with American vehicles choking the roads. To dislodge the remaining elements of the 1st Armored Division, German aircraft began bombing and strafing the American forces in the town.

CCB continued fighting the Germans well into the afternoon, but as nightfall approached it began a leapfrogging retreat to Kasserine Pass. The Germans took possession of Sbeitla late in the day. Believing his army had achieved all its objectives, Generaloberst Arnim ordered the 21st Panzer Division to remain in Sbeitla. His intention at that point was to send the10th Panzer Division north in a bid to capture Fondouk and Pichon passes.

The situation for the Americans continued to worsen further south when Rommel launched Operation Morgenluft on February 16. Generalmajor Kurt Libenstein, commanding the Afrika Korps, took possession of Gafsa while other troops remained at the Mareth Line. Libenstein advanced the following day to Feriana, where he was wounded by a mine. Command of the Afrika Korps devolved to Generalmajor Karl Bulowius.

With the Americans in full retreat, Rommel wanted to exploit the German success by capturing Tebessa. From Tebessa he wanted to strike northward, get behind the British First Army, and capture the port of Bone, Algeria. If he were able to disrupt the Allied supply line, Rommel hoped to compel the Allies to withdraw from Tunisia altogether. Rommel debriefed Arnim on February 17, but Arnim told Rommel that he had broken off his advance on Tebessa because of fuel shortages.

Displeased with Arnim’s performance, Rommel requested the following day that Kesselring assign both the 10th and 21st panzer divisions to him personally. Although he approved of Rommel’s plan, Kesselring said he had to first consult with Italian leader Benito Mussolini since Italian forces were involved.

Kesselring contacted Rommel a short time later to inform him that he could retain the Afrika Korps and also have the two panzer divisions he desired for the operation. Rommel’s command would be known as Group Rommel. As for the German-Italian Panzer Army on the Mareth Line, Marshal Giovanni Messe took command of it. It was rebranded as the 1st Italian Army.

Rommel was to strike northwest through Kasserine Pass for Le Kef in order to get behind the British First Army. Generaloberst Arnim received orders to conduct a diversionary attack against the British troops in the north to tie them down. To make sure Arnim carried out his portion of the plan, Kesselring flew to Tunisia on February 19 to keep a close watch on him.

Rommel ordered the 21st Panzer Division to assemble at the Sbiba Pass and the Afrika Korps to advance towards the Kasserine Pass. When it returned from Pichon, the 10th Panzer Division was to be placed on reserve. It would reinforce German forces at either Sbiba pass or Kasserine pass, depending on where a breakthrough seemed most likely.

While the Germans regrouped, the Allies scrambled to strengthen their hold on the Western Dorsal. “The longer they let us alone, the better we’ll be set,” said Fredendall. Reinforcements from Algeria and Morocco set out for the front lines in central Tunisia. LT. Gen. Anderson shifted the British, French, and American units in the Western Dorsal to strengthen positions, including Sbiba Pass and the southern approaches to Tebessa. Allied senior command left only a makeshift force at Kasserine Pass.

Kasserine Pass was situated 25 miles west of Sbeitla. Its width varied from 800 yards to one mile. Two djebels overlooked the pass: Djebel Semmama towered over the northern flank of the pass, while Djebel Chambi loomed over the southern flank of the pass. The Hatab River, flooded by recent rains, bisected the pass. The road through the pass emerged into a large basin known as Bled Foussana, which was surrounded by wooded hills. The road forked at that location, with Highway 13 leading west to Tebessa and Highway 17 turning north to Thala.

Colonel Anderson T.W. Moore, Commander of the U.S. 19th Engineer Combat Regiment, initially was given the task of holding Kasserine Pass. His troops specialized in construction and had minimal infantry training. Moore placed his engineers just inside Bled Foussana, a short distance west of where the road split. He deployed his troops in a three-mile-long line across the river. The 1st Battalion, 26th Infantry, with which Moore had recently been reinforced, took over the defense of Djebel Semmama.

Moore was further reinforced by eight tanks of Company I, 13th Armored; a battalion from 894th Tank Destroyers; two 105mm howitzer batteries from the 33rd Field Artillery Battalion; and a French 75mm battery. To further the defenses, patrols covered the high hills on the flanks of the pass and minefields were laid—although some of them were only partially covered with dirt or completely exposed. Moore’s plan was to stop the enemy while they advanced through the narrowest part of the pass.

After a German reconnaissance detachment had probed the pass that same day, Fredendall became convinced the enemy was planning a major attack there. “Go to Kasserine right away and pull a Stonewall Jackson,” Fredendall ordered Colonel Alexander Stark, the commander of the 29th Infantry, in an effort to spur him to conduct a solid effort. Stark arrived at the pass on the morning of February 19 and assumed command of the forces defending it.

Generalmajor Bulowius attacked the pass at dawn on February 19 with the 33rd Reconnaissance Battalions of the Afrika Korps. These crack troops came under tank, artillery, and small-arms fire. As their attack stalled, the Germans took cover in the foothills of Djebel Chambi.

Bulowius then ordered Panzergrenadier Regiment Afrika into action. The panzergrenadiers charged up the slopes of Djebel Semmama. The two sides fought heatedly for control of a prominent knoll on the hill’s shoulder. As the day wore on, Bulowius also committed the 1st Battalion, 8th Panzer Regiment, to the expanding fight. The Americans, though, contained the initial German assault, destroying five German panzers.

American reinforcements began arriving in the afternoon. These included a battalion of tank destroyers and a battalion from the 39th Infantry. Brig. Gen. Charles Dunphie, the commander of the British 26th Armored Brigade, arrived on the scene to confer with Colonel Dunphy’s brigade stationed 20 miles away at Thala.

Alarmed at what he saw, Dunphie reported his observations to Anderson. Anderson gave Dunphie permission to set up a blocking force on the road to Thala from Kasserine Pass. British Lt. Col. Arthur Gore’s force, which was known as Gore Force, consisted of armor, motorized infantry, and a battery of artillery. Also arriving late in the night was Lt. Col. William Wells and his 3rd Battalion, 6th Armored Infantry of the U.S. 1st Armored Division. These fresh troops reinforced the American infantry battalion on Djebel Semmama.

The Germans attempted to infiltrate the American positions throughout the night as fighting continued for control of Djebel Semmama, where an American infantry company was cut off. Some American units withdrew without permission, including a company of engineers, some tank destroyers, and two artillery batteries.

While fighting raged at Kasserine Pass on February 19th, the 21st Panzer Division launched an attack at Sbiba that was cut short by the fierce defense put up by Allied forces. Instead of pressing his assault against Sbiba, Rommel decided to make his main thrust against Kasserine Pass.

At 8:30 am on February 20, German artillery and Nebelwerfers (multi-barreled rocket launchers) began shelling the American positions at Kasserine Pass. In the assault that followed, Bulowius’ troops succeeded in cracking a portion of the American lines. The 10th Panzer Division arrived in the afternoon to reinforce the attack. Unfortunately, Arnim had withheld its Tiger battalion, thereby weakening its attack.

Rommel became increasingly impatient for a breakthrough given that Montgomery’s Eighth Army had arrived at the Mareth Line. He therefore ordered an all-out attack in the late afternoon. The 10th Panzer Division advanced on the right, while the Afrika Korps pushed forward on the left. The weight of the attack shattered the American defense, and the shaken American units retreated in disorder.

Exploiting his success, Rommel sent a battalion from the Italian Centauro Division racing westward on the road to Tebessa. The division made five miles before halting for the night. Meanwhile, the Germans advanced on Thala. Although Gore Force stalled the German advance for a time, the arrival of more panzers at dusk resulted in the destruction of Gore’s remaining tanks. Retreating with Gore Force was a handful of American tank destroyers, which was all that remained of an original force of 40. The Germans had at last succeeded in overrunning the American force on Djebel Semmama.

With Kasserine Pass in German hands, Rommel suddently became cautious. Concerned over the possibility of an Allied counterattack in the morning, he halted advances towards both Thala and Tebessa. With no attack materializing on the morning of February 21, Rommel ordered Bulowius to advance cautiously westward toward the passes at the rugged Djebel el Hamra.

Generalleutnant Fitz Freiherr von Broich, commander of the 10th Panzer Division, received orders to make a cautious advance north towards Thala. Seven miles west of the Kasserine Pass, Bulowius’ reconnaissance battalion ran headlong into Robinett’s CCB. Robinett had earlier been ordered to stop the enemy on the road to Tebessa. The German reconnaissance force quickly pulled back and waited for help.

Rommel decided that his main effort would be to push through Thala onto Le Kef. To deal with the Americans on his flank, he ordered Bulowius late in the morning to take the passes at Djebel el Hamra. The Germans soon encountered Colonel Henry Gardiner and his 2nd Battalion, 13th Armored of the CCB. Gardiner had deployed his tanks in a wadi using a bank for cover. With the support of artillery, Gardiner’s tankers engaged the German armor and infantry in a long-range firefight in the late afternoon. After an hour of fighting, the Germans broke off their attack. They were still four miles from Djebel el Hamra.

Rommel ordered Bulowius to swing around to the south and attempt to attack the Americans from the rear. In the darkness and pounding rain the Germans became lost. At dawn the next day the Panzergrenadier Regiment Afrika infiltrated through the Allies’ line and attacked Hill 812 near the Bou Chebka Pass. They managed to capture five howitzers and other guns of the American 33d Field Artillery Battery.

The panzergrenadiers found themselves stranded on the hill when the fog lifted. An attack by German armor and Italian infantry to aid them came under artillery fire. “The air was full of hardware and smoke and the sounds of a real scrap,” recalled Brig. Gen. Clift Andrus, commander of the 1st Division’s artillery.

Andrus’ guns stopped the attack cold. The Germans would get no closer to Djebel el Hamra, which lay two miles away, or to Tebessa, which was 23 miles away. Maj. Gen. Terry Allen, commander of the 1st Division, ordered an Allied counterattack. In the face of the counterattack, the Afrika Korps withdrew to the east.

The Germans initially had more success pressing their attack towards Thala. The lead elements of Broich’s advance eventually halted nine miles north of the Kasserine Pass when they came up against Dunphie’s force on a ridge. Brig. Gen. Cameron Nicholson, whom Anderson had dispatched to take command of all forces south of Thala, ordered Dunphie to ensure at all costs that the German armored forces did not reach Thala before nightfall. With 50 Mk III Valentine and Mk VI Crusader tanks and a complement of infantry, Dunphie entrenched. Meanwhile, the 5th Leicesters established a new line of defense a few miles south of Thala.

Broich launched his main assault in mid-afternoon. Dunphie’s lightly armored tanks were no match for the German panzers. By late afternoon, under the cover of a smoke screen, Dunphie withdrew his battered force to the last line of defense. Following closely on his heels were the Germans, with a captured Valentine tank leading the column. Through their ruse they succeeded in penetrating the British defense. A wild melee ensued; by midnight, the Germans controlled the ridge.

Dunphie’s stand had bought sufficient time for reinforcements to arrive from Algeria. Brig. Gen. Stafford LeRoy Irwin arrived in the early evening on February 21 with his 9th Artillery Division after a gruelling 735-mile forced march. His tired gunners labored throughout the night to get their guns into position. By dawn they were ready to add their firepower to the 36 guns defending Thala.

The British tanks then launched a desperate thrust against the German position outside of Thala. The Germans shredded the attack. The American heavy guns kept the Germans at bay, though, and Broich broke off his assault.

Blaming enemy reinforcements, the weather, and dwindling ammunition supplies, a seriously fatigued Rommel decided to end the operation. The battle for Kasserine Pass was over. Axis forces had suffered 2,000 casualties, while the Allies had suffered upwards of 10,000. The hard lessons that the Americans learned regarding the organization of their armored divisions would pay off in future campaigns in Italy and France.

Rommel began withdrawing his command from Kasserine Pass on February 23. That same day, Kesselring—who was deeply displeased with Arnim for his failure to support Rommel—put Rommel in charge of all Axis forces in Tunisia.

Although the two German offensives had cost the Americans heavily in terms of lives, equipment, and morale, their elite panzer forces had failed either to drive the Allies from Tunisia or even to capture the American supply depot at Tebessa. Moreover, in the reorganization that followed, Lt. Gen. George Patton replaced Fredendall on March 6. Patton introduced sweeping changes that resulted in a renewed sense of esprit de corps among the Americans that served them well when they resumed their offensive.

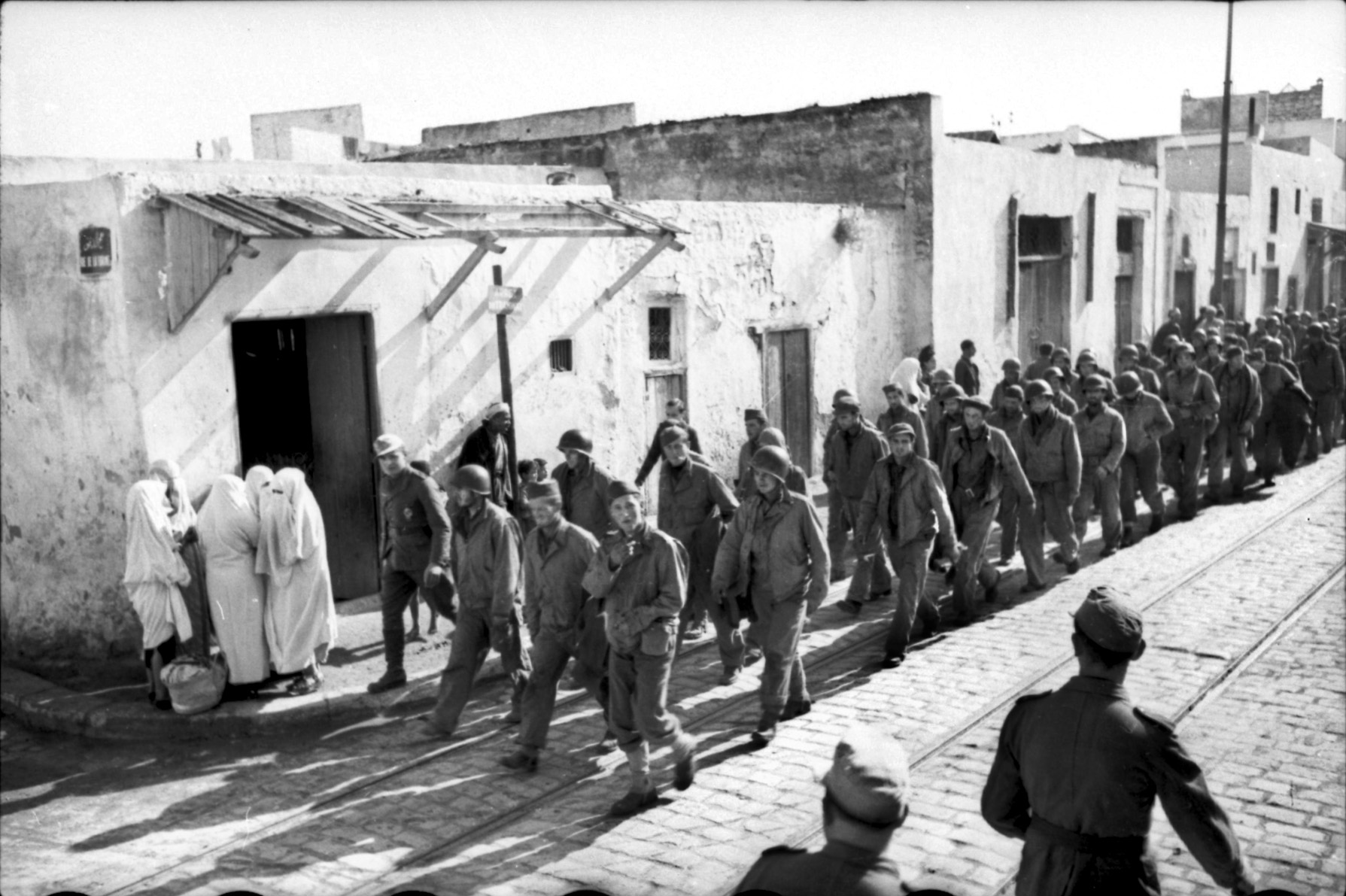

Rommel only served in his new role for about two weeks. He departed Tunisia on March 9 on sick leave. A renewed Allied offensive forced the surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia on May 13. The Allies led 272,000 German and Italian prisoners into a long captivity.