By Kelly Bell

The black uniformed German panzer crews climbed into their Panther tanks at 10 pm on June 8, 1944. Their objective was the village of Bretteville just west of the key crossroads of Caen opposite the beaches where the British had come ashore on D-Day two days before.

The engines roared to life, smoke poured from their exhausts, and the tracks clanked as they rolled into the black of night. Because of the threat of attacks on German armored columns by rocket-firing British Hawker Typhoons, it was essential that the attack go forward under cover of night.

The two companies of Panthers from Panzer Battalion I of the 12th SS Panzer Regiment were part of a kampfgruppe whose objective was to disrupt the advance of Canadian forces moving around the left flank of German forces organizing to make a stand at the city and possibly drive the British back to the beaches in the days to follow.

The kampfgruppe moved quickly toward its objective. Rather than having the panzergrenadiers participating in the attack ride atop the tanks, they rode the half dozen kilometers to their objective on motorcycles.

When the Germans arrived at their objective, the defenders were ready. Manning antitank guns, infantrymen of the Regina Rifles Regiment, 7th Brigade, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division scored a number of hits on Panthers at the front of the column. Hoping to take the defenders in the flank or rear, many of the tanks peeled off to the south, driving around the enemy’s flank to enter the village from the other direction.

The Panthers rolled into the town and began firing into buildings and into rows of dense bushes where enemy infantry was hiding. Soon a portion of the village was in flames. Thick smoke poured from burning buildings and destroyed tanks, making it doubly hard to see targets in the nocturnal fight. Some of the tank crews, lucky to escape their damaged tanks, ran for protection behind the panzergrenadiers or hitched a lift on friendly vehicles. The Canadians eventually made it too hot for the Germans to stay.

“Through my sight I saw a veritable wall of fire moving toward us about 900 meters away,” wrote tank gunner Leopold Lengheim. “There was no time to think, load—fire, load—fire, as fast as possible until it was all over for us as well. Hits to the slanted front armor and the gun ruined its adjustment; our fire lay way short. The next hit went exactly below the commander’s cupola. The cupola and the head of our commander were gone.”

The desperate and gruesome night fight at Bretteville was characteristic of the fighting over a two-month period between the Commonwealth troops and German troops at Caen. In the early days, the Germans launched multiple counterattacks to buy time for German troops stationed at other possible invasion areas on the French coast to reach the Normandy sector.

The Germans managed in the weeks following D-Day to derail the schedule of British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, who expected Commonwealth troops to capture Caen on the day after the landings. German Army Group B Commander Erwin Rommel urged his subordinates to rush additional units to Caen to prevent a breakout by Montgomery’s troops. Each commander committed the vast majority of his armor to the battle for Caen. It came as a cold shock to Montgomery and the Commonwealth troops that the steel-spined Germans would fight a two-month delaying action before being forced to relinquish the key objective to their equally determined foe.

Like other key cities in Normandy near the invasion area, Caen was an important road junction. The Germans sought to prevent the Allies from capturing it so as to deny them the ability to move east-west and break out from the bocage, which was the patchwork of fields divided by wooded embankments that offered every advantage to the defender and none to the attacker.

On the evening of June 6, Generalleutnant Edgar Feuchtinger’s crack 21st Panzer Division assembled south of the city and sliced through the British-Canadian linkup between Juno and Gold Beaches. The 192nd Grenadier Regiment drove all the way to the English Channel coast. However, the former Afrika Korps division’s armored elements lost contact with their accompanying infantry, and rather than following it and strengthening the potentially crucial wedge between the invasion beaches the panzers veered westward about five miles behind their advance units and blundered into Allied antitank positions outside Bieville and Periers and were quickly pinned down.

While the 192nd’s infantry waited in vain for its tanks to arrive, the situation stagnated. This in itself was a positive development for the Germans. If they could hold the corridor long enough to pack it with armor, artillery, and men, the British beachheads would be isolated and in jeopardy. To the north at Calais there were about 200,000 German troops waiting for a second invasion the Wehrmacht suspected would come there. If German Führer Adolf Hitler were to decide to send these reserves to Normandy, they could have a very consequential influence on the still-vulnerable Allied foothold.

Realizing the peril, 21st Army Group Commander Montgomery rushed fleets of troop-laden gliders into the Nazi-held salient in advance of the beach landings. With virtually no air support, the Germans were unable to stem this mini-invasion from the sky, and when reinforcements and supplies failed to arrive they were forced to back out of their vital real estate and fell back to Caen. The invaders’ beachfront holdings were now more secure, but they could be nothing but a stepping-off point for the inevitable liberation of western Europe, and in the corn-growing belt just in front of them their route was blocked by a ruthless and capable foe.

The vanguard of the 12th SS Panzer Regiment of the 12th SS Panzer “Hitlerjugend” Division had begun arriving southwest of Caen on June 6 to reinforce the 21st Panzer Division. The Hitlerjugend Division was led by Brigadeführer Fritz Witt. Panzer Battalion 2, which was equipped with Panzer IV tanks, arrived during the night. Panzer Battalion 1, which was equipped with Panther tanks, arrived the morning of July 7.

On the morning of June 7, the 21st Panzer and the lead elements of the 12th SS Panzer Hitlerjugend Division, which was led by Brigadeführer (brigadier general) Fritz Witt, were outside the city while preparing for a joint Army/SS attack on Sword Beach. Witt issued the following order for an attack: “Attack the enemy on the left of the railroad line Caen-Luc sur Mer and drive him into the sea.” The attack was to begin at 4 pm, but the enemy’s initiative would force the commitment of much of this force before that time.

While Panzer Regiment 12 was still arriving that morning, the commander of the 25th SS Panzergrenadier Regiment, Standartenführer (general) Kurt Meyer, was surveying his area of approach from the steeple of the 12th-century Abbaye d’Ardenne three miles northwest of Caen. Meyer was startled by the sight of an advancing armored column. It was the Canadians of the 27th Tank Regiment and 2nd Armored Brigade making a leisurely and (as it turned out) ambitious attempt to take coveted Carpiquet airfield.

Evidently unaware of the powerful, nearby hostile presence, the Canadians rumbled casually along a road lined with camouflaged German Panzer IV tanks and artillery. Meyer, who had at his disposal a battalion of panzergrenadiers and a tank battalion, personally directed the German attack. By then, the Germans at Caen had 50 tanks ready to take on the enemy. When the unsuspecting convoy reached the Caen-Bayeux Road, Meyer screamed “Attack!” into his field microphone.

A reconnaissance by four Panzer IVs of Company 5, Panzer Battalion 2, along the Franqueville-Authie Road ran headlong into Shermans of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers at 2 pm. The doughty Fusiliers managed to knock out three of the four German tanks in a brief but bloody action. When apprised of the bad news, Panzer Regiment 12 Commander Obersturmbannführer (lieutenant colonel) Max Wünsche ordered a general attack by all of the available panzers from II Panzer Abteilung. “Panzers, march!” he shouted into the radio. Hearing the order, all tanks of Companies 5 and 6 of Panzer Battalion 2 positioned to the left of Abbaye d’Ardenne started their engines and lurched forward to hunt for the enemy. The Mark IVs suddenly appeared as if out of nowhere on the enemy’s left flank. The unplanned German ambush was a total rout. The Sherbrooke Fusiliers pulled back, leaving in their wake 21 knocked out Shermans. Meyer had pushed to within six miles of Sword Beach. Unfortunately, he had not yet been reinforced with additional armor from either the depleted 21st Panzer or the soon to arrive Panzer Lehr Divisions.

Trying to follow up his triumph with an assault on Sword Beach, Meyer deployed his forces northward. Additional Canadian armor promptly assailed his flanks. When Meyer came under fire from field artillery, naval artillery, and ground attack aircraft, he realized the odds were too great, broke off the advance, and returned to Caen.

The lengthiest siege of the war in the West was unfolding, and Montgomery’s frustration would mount steadily in the coming weeks. Stung by the German counterattacks, Montgomery on June 8 ordered British Second Army commander General Miles Dempsey “to develop operations with all possible speed for the capture of Caen.”

On June 9, the 15,000 soldiers of the Panzer Lehr Division began arriving at the front and took up a position on the far left flank of the German line, blocking the Commonwealth advance toward Caen.

Over the next few days the situation on the northern outskirts of Caen stalemated with the 3rd Canadian and 3rd British Divisions keeping the pressure on and tying down the 12th SS and 21st Panzer Divisions while the British 7th Armored Division attempted to wheel around in a great arc, outflank the waiting Panzer Lehr Division, and assault Caen from the west. Things went terribly wrong.

The command of the 1st SS Panzer Corps had recognized the need to bolster the left flank of the Panzer Lehr Division west of Caen but could not draw off any of the scant tank assets of the three armored divisions already deployed at the front. The command, therefore, decided to order those elements of Heavy Tank Battalion 101, which had just arrived at the front and had not yet been committed, to protect Panzer Lehr’s unanchored left flank. Company 1 of the heavy tank battalion took up a position 10 kilometers northeast of the outlying village of Villers-Bocage, and Company 2 established itself behind the other company two miles northeast of the village. Company 1 was led by Haupstürmführer (captain) Rolf Mobius, and Company 2 by Oberstürmführer (1st lieutenant) Michael Wittmann.

On the morning of June 13, the 22nd British Armored Brigade made it as far as the outlying village of Villers-Bocage. Wittman was watching. Angered at the nonchalance of the overconfident Englishmen, Wittmann (who had only five of his Tiger tanks on hand) attacked the column alone while his other four tanks laid down covering fire. Wittmann knocked out four Sherman tanks from 80 meters. He then roared up to the column, turned his Tiger parallel to it, and drove alongside the column in the direction of the march, blasting enemy tanks. The other tanks of his company fell in behind him and rounded up more than 200 prisoners.

Wittmann eventually was joined in the turkey shoot by Company 1, and together the two Tiger tank companies knocked out a large number of British tanks. Wittmann spent the day destroying everything Allied he could get in his sights, and that evening, with infantry from the 2nd SS Panzer and Panzer Lehr Divisions strengthening the German line, the surviving “Desert Rats” of the 7th gave up and fell back to Livry five miles to the east.

Wittmann had finished the day with 25 British tanks to add to his tally of 119 Soviet machines he had destroyed in almost three years on the Eastern Front. His exploits this day earned him the rare swords addition to his Knight’s Cross and a promotion to captain. More significantly, he and his fellow SS had pulverized the armored spearhead of Montgomery’s main thrust. Another major drive on Caen was convincingly stopped. The Germans had shown they were eager to fight and would strive to inflict maximum damage on the British and Canadian forces advancing on Caen.

Montgomery was anxious about being overshadowed by the Americans. Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins’s VII Corps was securing the Cherbourg peninsula on June 22. That same day the British and Canadians saturated the Nazi positions in front of Caen with a massive artillery bombardment before their next advance. It was the 16th day of the invasion. Montgomery had confidently scheduled Caen to be captured on D-Day plus one. It had been two weeks since June 7, and the chagrined field marshal planned to ford the Odon and Orne Rivers, take vitally strategic Hill 112, then send his forces around the city and secure it via a flanking maneuver. On paper it looked easy.

The onrushing British collided with the well-equipped, fanatical teenagers of the 12th SS Panzer Division but managed to force an expensive penetration through antitank positions. If the Allies could consolidate a breakthrough across the Odon Valley, Caen would be successfully outflanked and the German lines in northern France seriously breached.

Initially things looked promising for the British. Apart from the overworked 12th SS Panzer Division, the British were opposed only by decimated units and lone, panzerfaust-packing grenadiers lurking in hedgerows and orchards. These troops and a few Tiger and Panther tanks managed to slow the encroaching swarms of infantry-laden Shermans, but His Majesty’s soldiers were many and determined.

By the end of June, Hill 112 was secure, enabling the Scottish 15th Division to cross the Odon and set up on its left bank. At daybreak on June 30, the 2nd SS Panzer Corps, with heavy mortar and artillery support, launched a sudden counterattack on the strategic heights. Although codebreakers had warned them of the assault and they had crowded tanks, antitank artillery, and part of a machine-gun battalion onto the hilltop, the speed and power of the dawn panzer charge knocked the British off balance, and Hill 112 again changed bloody hands. If only for the moment yet another Allied threat to Caen was averted.

Despite punishing attacks by Typhoons, the Germans had managed to amass 71/2 panzer divisions around Caen by the end of June. Between them, the divisions had 150 heavy tanks, both the Tiger and newer King Tigers, as well as 250 medium tanks. Montgomery had been fought to a standstill, so it seemed. He issued a directive on June 30 indicating an intention to hold in front of Caen on the Allied left flank in anticipation of an American breakthrough on the Allied right flank. But his headquarters continued working on plans for an eventual breakout on the left.

On July 4, Canadian forces reached the heights overlooking Carpiquet airfield. One after another the outlying villages of Ste. Honorine-la-Chardonnerette, St. Manvieu, Blainville, Periers-sur-le-Dan, Anisy, Villons-les-Buissons, and Norrey-en-Bessin fell to the inexorably advancing Commonwealth forces, ringing the main objective in an almost complete encirclement. Eight centuries earlier William the Conqueror had set sail from Normandy to add England to his dominion. Now a far greater invasion in reverse had reached the outskirts of the ruins of his capital.

Montgomery called this offensive to finally drive the Germans from the ruins Operation Goodwood, and in preparation the Royal Air Force (RAF) sent the Avro Lancasters and Handley Page Halifaxes of 625 Squadron on a massive raid the evening of July 7. The heavy bombers unloaded 2,000 tons of high explosives onto the already devastated city. For an hour the bombs drummed to earth as Germans and imprudent townspeople who had not heeded the warning of the impending holocaust delivered via leaflets earlier in the day cowered in stunned terror as their world exploded around them. One young mother who watched two children blinded by flying glass shards covered her own little boy’s face with a pillow as she felt the “whole world shudder. It went on and on for 50 minutes with a single break of five minutes.”

Furthermore, Allied artillery fired more than 80,000 shells in support of the coming push but overshot the German defense perimeter and killed approximately 5,000 French civilians still in the city.

But German losses were insignificant. The bombing and shelling actually raised the morale of the waiting defenders as they listened in glee to the off-target pounding. Montgomery kicked off his offensive, codenamed Operation Charnwood, at 4:20 am on July 8 with the Canadians starting at 7:30 am. The Allies were stunned at the ferocity of the resistance they encountered as Meyer’s men fought with their typical abandon. Still, the decimated 16th Luftwaffe Field Division had essentially collapsed, dangerously exposing Meyer’s right flank. Also, the British 9th Infantry Brigade and 33rd Tank Brigade had, by midmorning, penetrated into Caen’s suburbs. Elsewhere on the sprawling battlefield the British were making progress.

The British pushed the 1st SS Battalion out of Milius, leaving adjacent Epron in danger of being liberated. What was left of the 2nd SS Battalion was encircled in Glamanche, and by 4 pm the British Royal Warwicks had reached St. Contest. In Buron the Canadians had trapped the 3rd SS Panzergrenadier Battalion. At 5:30 pm a counterattack by two platoons of the 3rd SS Panzer Company was hurled back, leaving Commonwealth forces at nightfall still in possession of the day’s hard-earned gains. At great cost (262 men killed in the North Shore Regiment alone) the Canadians had taken the towns of Gruchy, Authie, Franqueville, Cussy, and Carpiquet airfield. In other areas the attack fell short of its objectives.

British attempts to reach and secure the Orne River bridges in Caen were blocked by minefields and intense artillery fire. Still, Meyer’s command was being bled white, and on July 8, 1st Panzer Corps Chief of Staff Fritz Kramer gave him grudging permission to fall back to the Orne’s southern bank. That evening Rommel removed all his heavy weapons from Caen’s city proper and set up a new defense line with what was left of Meyer’s troops on the southern bank. In the darkness the Allies did not seem to realize their foe was slipping away, and the Germans escaped to set up a powerful riverside position.

The British reached the center of the city on the afternoon of the 9th, but tons of bomb-blasted debris blocked further progress. Still, they had finally reached their D-Day plus one objective—slightly more than a month late. Even at that point the Germans held the southern part of the city. So far Montgomery’s command had taken 3,817 casualties and lost 80 tanks. By ratio the Allies had lost six times as many men as the Germans during the Caen offensive. The tactical bombing was an even greater failure.

The sight of successive waves of medium and heavy bombers droning overhead was heartening to the British and American ground forces, boosting their morale. However, the tangible results were virtually nonexistent. Professor Solly Zucherman served as Royal Air Force Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder’s scientific advisor. An authority on Allied bombing policy, he visited the bombed area as soon as it was secured and was appalled at what he found. Despite the ghastly devastation he could locate virtually no sign of German dead or of destroyed Wehrmacht equipment.

Apart from obliterating an area of profound historical and cultural significance the poundings were militarily ineffectual. A doctor who remained in Caen and survived later wrote, “The bombardment was absolutely futile. There were no military objectives. All the bombardment did was choke the streets and hinder the Allies in their advance through the city.”

It also failed to achieve its aim of disrupting the transfer of German forces from the British to the American sectors. The 2nd SS Panzer and the Panzer Lehr Divisions moved westward to effectively block the advance of General Omar Bradley’s First Army. By July 10, the First Army had suffered 40,000 casualties, forcing Bradley to halt his slow progress while his command rested, repaired, and absorbed replacements.

Rommel had managed to convey four sizable forces of fresh reinforcements from his 1st and 19th Armies to the Caen salient, enabling him to fight his old foe Montgomery to a standstill. The Germans’ ability to move troop columns across unbridged rivers despite heavy air interdiction took Montgomery by surprise and reminded him of a grim possibility that had troubled him for some time. What if Hitler decided to abandon the relatively unimportant Mediterranean coast and shift German forces there north? If he took that course of action, Hitler might be able to stagnate or even turn back the Allied advance. Thus, the British had to find a way to sustain their momentum and compel the enemy to commit all his reserves to engagements already or soon to be in progress and initiated by the Allies.

By keeping the Germans tied up in locations of his own choosing, Montgomery would make it impossible for them to counterattack through some weakly held part of his line. He was especially worried about where his lines intersected the American ones between Caumont and St. Lo. Hitler was indeed considering sending his forces against this vulnerable spot, and only constant pressure elsewhere was keeping the Wehrmacht off it. A strike sorely needed to be made soon to ensure against this dire possibility.

It had been two weeks since the expensive, futile attempt to secure the crucial high ground southwest of the city—specifically Hill 112 in the angle of confluence between the Orne and Odon Rivers. If a second, finally successful blow could be made here things would be looking up with the durable Nazi garrison at last outflanked and outmaneuvered. It was also an obvious place for Montgomery to strike. His beachhead was deepest and most secure to the south, around the city of Bayeaux, but it had moved inland as far as possible because the countryside in front of it consisted of a series of steep, forested ridges bisected by river bottoms and sunken lanes. All this led up to the cliffs, promontories, and deep gorges of the Norman interior. The Germans fully expected another attack on Hill 112 and beyond. The only thing they were unclear on was when.

It had to be soon. Reserves were shrinking. With his flow of replacements steadily ebbing, Montgomery contacted an increasingly impatient Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower on July 12: “Am going to launch a very big attack next week. VIII Corps with three armored divisions will be launched to the country east of the Orne.” The attack he was referring to was Operation Goodwood.

With his predilection for deep thrusts through narrow breaches, Montgomery was habitually menaced on his flanks. To eliminate this danger he contacted RAF Bomber Command and the U.S. Army Air Forces to provide tactical support.

Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris was unhappily aware of the dismal results of the recent bombing of Caen proper, but eventually agreed to provide 1,056 Lancasters and Halifaxes for yet another major raid. They were to line the entry point of the attack corridor with 5,000 tons of high explosives set with delayed fuses to crater the ground, making it difficult to transfer panzers. This also would smash defenses throughout the target area between the Colombelles Steelworks on the banks of the Orne to the west and the villages below the Bois de Bavent to the east. The U.S. Eighth and Ninth Air Forces would hammer the length of the corridor and its exit at Bourguebus with fragmentation bombs from 1,021 medium and heavy bombers in a synchronized Anglo-American attack that was the heaviest ever in support of ground forces.

Goodwood sent more than 10,000 vehicles of all classes (including 870 tanks and 680 tracked carriers) against the defenders. Late on the night of July 17, the 11th Armored clanked as quietly as possible across the Orne. Next came the 7th and Guards Divisions, passing through the gaps sappers had for days been clearing in the defensive minefields. It was 1 am as the force began assembling at the jump-off point, and with H-hour set for 7:45 am the tank crews, already exhausted by two days on the road, tried to snatch some sleep. At 5 am, the first wave of bombers droned overhead, and within seconds the region in front of the armored force was a churning purgatory of titanic explosions.

Several miles out in the English Channel sat the battleship HMS Roberts. The last time she had seen action was the World War I Battle of Jutland, but now her elderly but enormous 15-inch rifles were doing such a masterful job of pounding the German antiaircraft positions that only six of the massive air armada’s planes were downed.

The unfortunate Nazis beneath these waves of multi-engine, explosive-laden planes were terrifyingly shocked to be deemed worthy of such devastating attention. The landscape-altering storm was indeed like nothing witnessed in the history of warfare. Panzer radio operator Werner Korstenhaus later described it as “a bomb carpet, regularly plowing up the ground. Among the thunder of the explosions we could hear the wounded screaming and the insane howling of men who had been driven mad.”

An undetermined but horrific number of Germans lost their minds, committed suicide, were buried alive or blown to atoms by the unearthly bombardment that overturned 63-ton Tiger tanks. Tanks not wrecked by the explosions had their guns, exhausts, air filters, and engine grids choked by the tons of dirt thrown up by the bombing. Their gun sights were knocked off target, and if their motors cranked at all they ran roughly and grudgingly. The infantry fared even worse.

Surviving members of the Luftwaffe’s 16th Field Division were so shaken by their ordeal that they lost their muscular control and could not be marched to POW compounds for several hours because they were unable to walk in a straight line.

Montgomery and his planners had fingered elements of the 21st Panzer Division as the greatest threat to the coming Allied advance, but the Douglas Havocs and Martin Marauders of the U.S. Ninth Air Force had raked the 21st murderously. Also, the division had been in continuous combat since D-Day and was significantly depleted even before the air attack. Its surviving members, however shaken, were still proud professionals and had no intention of yielding anything easily.

Drowned out by the last bomb detonations were the crankings of hundreds of tank engines presaging the advance of the huge Commonwealth force down the pathway between Honorine-la-Chardonnerette and Escoville. To the left of the tank column was the accompanying infantry—the 23rd Hussars. Contrary to plans, the foot soldiers were forced to wait while the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment crowded through gaps in the minefield, and the infantry fell behind the armor. Rather than move ahead as a consolidated force, the massive attack group lost cohesion and formed a long, straggling line.

Before even encountering any defenders the divisional reconnaissance company, the Northhamptonshire Yeomanry, lost four Cromwell tanks to mines missed by the sappers. Ahead of them the infantry had made it past the minefields and come under fire from German field pieces ensconced in the sprawling ruins. These foot sloggers sorely needed armored support.

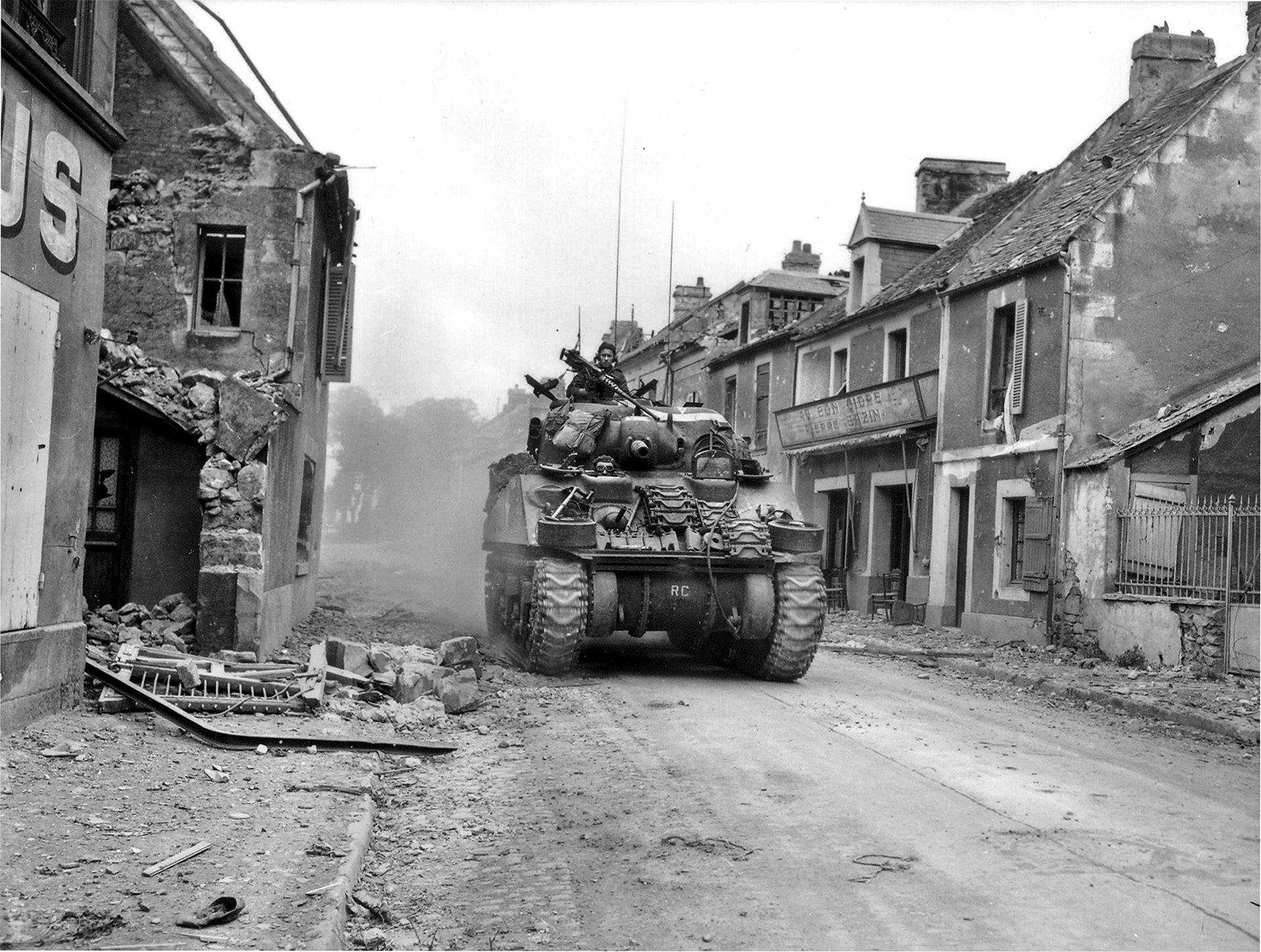

The infantry elements of the 11th Armored, 3rd Monmouth, and 1st Hereford Brigades reached Cuverville about 8:30 am and accepted the surrender of a number of shellshocked Germans numbed by the night’s bombing, but preliminary bursts of automatic weapons fire from the debris made it clear to the riflemen that the airmen had not finished the job for them. The brigades commenced mustering for a frontal assault. This in itself was time consuming, and the tanks were already beyond the cluttered city streets, having bypassed them before dawn and resumed moving farther down the corridor and toward yet more Nazi strongholds. By the time the foot soldiers finished clearing the enemy from Cuverville, their motorized comrades were far ahead and, without the infantry, wide open for a flank attack.

The Shermans were approaching the 10-foot-high railroad embankment of the Caen-Vimont line. Crossing was tricky. Each machine had to crawl diagonally to the top, ease itself over the tracks, then rush at top speed down the incline without exposing itself too long against the skyline. A few of the Germans’ dread 88mm field pieces had indeed survived the night.

The column made it over the railway, but the cloud of dust it kicked up alerted Oberst (colonel) Hans von Luck of the 21st Panzer Division. Watching from an orchard in the lofty village of Cagny, he noted how the mechanized force would skirt that town, passing between it and neighboring Le Mesnil-Frementel. He also took into account the surprising absence of covering infantry.

Hastily assembling five 88mm guns in the orchard, von Luck ambushed the column and knocked out 12 tanks, but his attack came too late. By then more than 100 Shermans had already passed Cagny and were en route to their final destination—Bourguebus.

More time and lives were lost in another attack outside Cagny, this time by six Tigers from the 503rd Heavy Tank Division, which knocked out nine of the grenadiers’ tanks. Running off high-octane gasoline rather than diesel, the Sherman was notoriously flammable and outclassed in other ways by the generally larger, better armored and gunned panzers they faced in France. This was more than offset by their greater speed, maneuverability, range, mechanical reliability, and marked numerical superiority. The 3rd Royal Tank Regiment had been shielded from von Luck’s 88s by the mass of friendly armor between it and the ambush. Thus far during the advance they had lost just one machine, but as they crossed the Caen-Vimont railway they came under fire from mortars and three self-propelled 105mm guns.

The 3rd quickly lost three of its 19 tanks, and as its commander, Major Bill Close, recalled the squadron on the left “also had several tanks blazing furiously. My orders were to press on and bypass the village.” Obeying instructions to advance rather than pause and fight, Close’s command ducked into a railway tunnel and made it to the other side where a railroad embankment shielded it from enemy fire. It was soon joined by the rest of the regiment. Ahead, across 3,000 yards of open countryside, lay their temporary objective—the villages of Bras and Hubert-Folie.

In the rear of the main body of the 11th Armored, its commander, Maj. Gen. G.P.B. Roberts, was close to the action in his Cromwell headquarters tank. Assessing how the Guards Armored Division had shored up the eastern edge of the armored corridor, freeing him from fear of counterattack from that sector, and his western flank had left the suburbs and was moving into the city proper, and how the 7th Armored was approaching from the rear with 250 fresh Shermans and Cromwells, things were beginning to look hopeful for this necessarily tentative operation. Furthermore, the 3rd Royal Tanks and Fife and Forfars Divisions still had 40 battleworthy Shermans apiece and were resolutely advancing abreast with just the small towns of Four, Soliers, Hubert-Folie, and Bras between them and Caen.

Their enemy, however, since late 1941 had been learning in Russia how to mend gaping holes in his front lines with improvised units stitched together from rear-echelon personnel. Resourcefulness and flexibility were deeply ingrained in the German way of thinking, and the defenders had wisely spent the time bought by von Luck’s attack.

General Edgar Feuchtinger of 21st Panzer had lined the summit of Bourguebus Ridge with his engineer battalion and divisional reconnaissance battalion. These scout car crews, motorcyclists, bulldozer drivers, and mechanics would keep the British busy while the 1st SS Panzer Division Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler prepared a counterattack.

On the morning of July 18, the crack Liebstandarte Adolf Hitler left the southern perimeter of Caen and, keeping a wary eye on the sky, moved to new positions between Bourgebus and Bras at an elevated spot overlooking the open plain that soon would be literally filled with British armor. Hiding in a labyrinth of sunken roads, the Mark IVs and Panthers had adequate cover versus an opposing force advancing naked over open ground. The tank carrying the RAF forward ground controller had been blown up, so the tankers were now unable to directly call for air support.

About 3 pm, the Fife and Forfars and 3rd Tanks approached the German-infested high ground. Captain Robin Lemon of the 3rd said, “It was just when the leading tanks were level with Hubert-Folie when the fun began. I saw Sherman after Sherman go up in flames, and it got to such a pitch that I thought that in another few minutes there would be nothing left of the regiment. I could see the German tanks milling about just behind Hubert-Folie and over to the left.” It was the Panthers of the 1st SS, whose veteran crews were so accurately shelling the British with guns that outranged the Shermans and Cromwells.

To the rear the 23rd Hussars saw the smoke of battle and came rushing to help, but there was little to be done. The Fifes were wiped out, and survivors of the other units were withdrawing under fire. Montgomery’s forces left 106 tanks burning in the barren cornfields south of the city. At about 5 pm, the Northhamptonshire Yeomanry sent its Cromwells in a final attempt to continue the thrust’s momentum beyond Caen, but again the Germans, with their panoramic view of the battlefield, were ready, and the Yeomen clanked back in crestfallen defeat minus 16 of their machines.

Although he had finally managed to take all of Caen, Montgomery had not accomplished the major aim of driving past it and depriving the Nazis of the ability to counterattack. The Wehrmacht would damagingly strike westward from the towns of Mortain and St. Barthelemy on August 7. Close inspection and hindsight would later reveal that the seemingly disastrous day of July 18 did have positive results. While the bulk of German strength was occupied south of Caen, Canadian forces secured all the eastern bank of the Orne, consolidating the Allied hold on the city.

Furthermore, it had also been a costly battle for the Germans. Between them the 21st Panzer and 1st SS Panzer Divisions lost 109 tanks and half their precious 88mm guns that day. The Allied bombing wiped out the 16th Luftwaffe Field Infantry Division, and two other panzer divisions that had been scheduled to oppose the Americans were now compelled to stand watch on the British front. The ferocity of the Allied air and ground assaults had shaken the German high command, whose ranks were further distracted on July 20 when news arrived about the faraway attempt on Hitler’s life.

The 5,537 Commonwealth troops who perished during Goodwood had not died in vain. Although their advance had staggered to a bloody, premature halt they enabled the Americans to finally break out of their confinement in Normandy during Operation Cobra, clearing the way for Allied forces to complete their task of liberating Europe.

Montgomery’s career and reputation would survive this wrenching campaign. There was no way it could have been won easily, and it is arguable whether any other commander would have done better.

William the Conqueror’s city was now controlled by soldiers from the nation he had defeated so many centuries earlier. They would not be staying there long.