By Peter Kross

During World War II, Switzerland was one of the few neutral countries to survive unscathed amid the death and destruction that was being heaped upon the rest of Europe. Strategically located on the borders of France, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Czechoslovakia, Switzerland was an outpost where spies and covert agents of all the warring parties kept a close eye on each other and used Swiss territory to smuggle both people and material into and out of its wartime neighbors.

Into this highly charged political atmosphere the newly created Office of Strategic Services (OSS), headed by William Donovan, sent one of its most trusted officers to Bern to establish an intelligence listening post. That man was a well-connected, socially prominent diplomat and lawyer named Allen Dulles. From his base in Bern, Dulles would fashion a well-organized intelligence gathering operation whose agents were sent into occupied France, Italy, and Austria, as well as making covert contact with the small band of anti-Hitler military officers who were planning to assassinate the Nazi leader. In doing so, Dulles created the model for how a well-organized covert agency was to operate.

Allen Dulles came from a distinguished and politically well connected New York family. His maternal grandfather, John W. Foster, was Secretary of State under President Benjamin Harrison. His great uncle, John Welsh, was the U.S. Ambassador to London in the 1870s. Dulles graduated from Princeton University in 1914 and taught school in India. He began his diplomatic career in May 1916, when he was appointed the third secretary in the American Embassy in Vienna, Austria.

One day at the embassy, Dulles received a call from a young revolutionary Russian figure named Vladimir Lenin. Lenin wanted to meet with someone in the U.S. Embassy. Dulles refused the meeting, saying that he had a date and could not cancel it. In later years, Dulles would never forget that nearly fateful encounter with one of the most important figures of the 20th century.

In 1920, shortly after he married his long time sweetheart, Clover, Dulles was posted to Constantinople in Turkey where he assumed the post of first secretary to Admiral Mark Bristol, the U.S. Commissioner of the Allied tripartite pact which included both France and England. Their job was to oversee Allied interests in Turkey in the aftermath of World War I. He was tasked with the assignment of securing a peace treaty with the Turks, as well as keeping a close eye on the vital Rockefeller family oil interests (Standard Oil) in that country.

After the United States entered the war in December 1941, Dulles began a career in intelligence that would last his entire life. In 1941, he joined the newly created Office of the Coordinator of Information, the predecessor of the OSS, and ran its New York office. Dulles’s agents specialized in the collection of information from German emigres to America.

Dulles was a proponent of increased American aid to Britain and was vocally interventionist in his foreign policy pronouncements. In 1936 he co-authored a book called Can We Stay Neutral (with Hamilton Fish Armstrong), in which he called for firm American military ties to Britain.

Dulles took up shop in room 3603 in Rockefeller Center in New York, the same quarters as that of William Stephenson’s British Security Coordination. Stephenson shared his most important strategic intelligence with Dulles and his COI. As far as William Donovan was concerned, the United States needed its own intelligence agents inside Europe, not just second hand scraps of information at home. After Pearl Harbor, Donovan convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt that if America was to become a prime player in the international intelligence gathering business, it needed a secure place of operation. That location, according to Donovan, was Switzerland.

Donovan’s notes to the President read in part, “Switzerland is now, as it was in the last war, the one most advantageous place for the obtaining of information concerning the European Axis powers. Analysis of the telegrams reaching the State Department from various posts in Europe in which we still have representatives shows that the information from Switzerland is far more important than from any other post.”

Dulles lobbied Donovan for an overseas posting, and when the OSS chief inquired if he would be interested in London, Dulles begged off. Instead, they all agreed that Dulles would be offered the job in Bern, Switzerland, right in the heart of Europe, a scant few miles from the fighting.

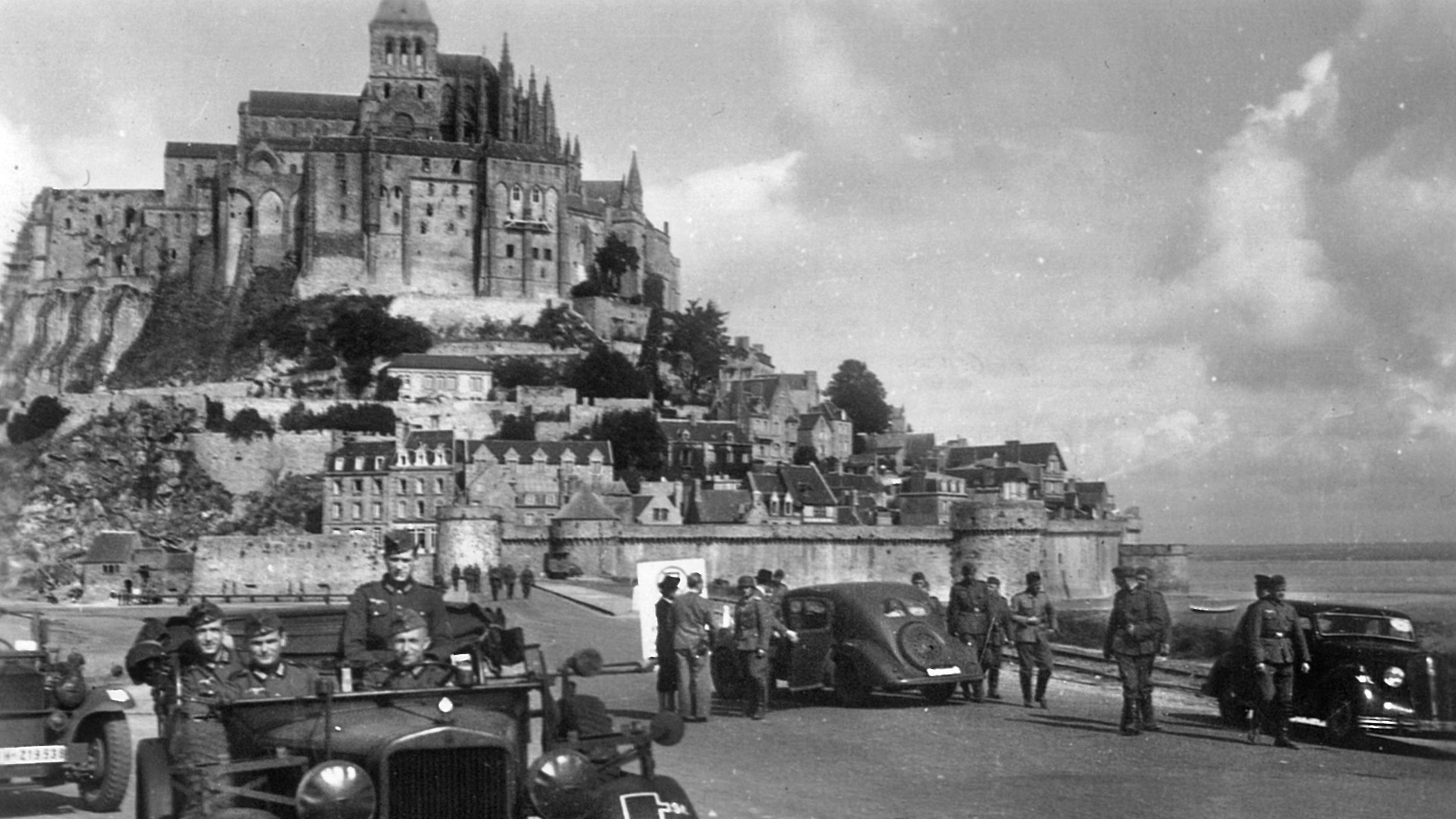

Switzerland was the Mecca for spies and counter-spies from all the warring nations, a place where the lights burned brightly, the stores were well-stocked, and everybody knew one another’s business. Swiss intelligence kept a close watch on all these foreign agents, eager not to offend Hitler, Mussolini, or Roosevelt. It was into this hotbed of intrigue that Dulles would enter and play his clandestine role. First though, he had to get there.

While Dulles waited for his official papers to be approved by the State Department, a few accounting considerations had to be worked out. Dulles decided not to accept any regular salary, but insisted that the OSS repay him for his expenses. Donovan assigned Dulles the code designation of “110” along with the title of “Special Representative of the President of the United States.” In effect, he was the OSS station chief in Bern, the number one spy for America in Switzerland.

Dulles finally left the United States on November 2, 1942, bound for Lisbon, Portugal, via the Pan Am flying boat. His original plan was to travel by train into Spain, across Vichy France, and finally ending at his destination of Geneva, Switzerland. Unfortunately, his travel plans turned out quite differently. En route, Dulles’s plane to Lisbon was delayed a few days in the Azores. He finally arrived in Lisbon and then departed for Barcelona, Spain, where he planned to travel by train to Vichy-controlled France.

While in Barcelona, Dulles learned that the Allies had launched Operation Torch, the invasion of North Africa. Dulles feared that the Germans would stop his train and detain him for the duration of the war. He decided to stay on the train and take his chances. With help from the local French gendarme, Dulles waited until the local Gestapo officer went on his break and took advantage of the opportunity to slip unnoticed into Switzerland. It was only by sheer chance that Dulles’s espionage mission to Switzerland did not end before it began.

Dulles arrived in Switzerland with $10,000 in cash and a mandate to perform a “special duty” mission. He later said of his first day in Bern, “It (his arrival) had the result of bringing to my door purveyors of information, volunteers and adventurers of every sort, professional and amateur spies, good and bad.” The first man he contacted in Bern was an Austrian lawyer named Kurt Grimm who had a business relationship with Dulles’s old law firm of Sullivan and Cromwell. Grimm saw to it that Dulles was outfitted with new clothes and, more importantly, found him a posh home. The address was 23 Herrengasse, a ground floor apartment in a 14th century townhouse at the end of a cul-de-sac, a perfect place in which to watch the street for any unwelcome visitors. In a bit of bravado on his part, Dulles had the local authorities turn off the street light adjacent to his apartment throughout the war. This allowed the identities of his clandestine visitors to be kept a closely guarded secret.

Dulles began his clandestine work with a grand total of two secretaries, who typed his correspondence and ran the office. By the time the war ended in 1945, he had a total of a dozen OSS staff members performing all kinds of intelligence related tasks. In time, the all important X-2 (OSS Counter-intelligence) made its headquarters in the same building, only feet from the boss’s inquiring eyes.

The British had their own, large intelligence base in Bern, and Dulles was aided in his initial weeks in the city by Henry Baldwin, a former butler and intelligence operative in Egypt. Baldwin performed the less glamorous, yet vital jobs of getting cars for OSS use in Bern, arranging for trains and bus stations to be watched, the tapping of telephones, and even the opening of mail addressed to other people.

Dulles’s British counterpart in Bern was MI-6 officer Count Frederich “Fanny” Vanden Heuvel. Dulles and Vanden Heuvel got on well together and made an arrangement whereby their respective agents would not try to recruit each other’s sources. The one exception to the rule was the use by both the British and the Americans of the services of a politically well connected Polish widow named Madame Halina Szymanski, who happened to be a mistress to Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, chief of the German Intelligence Service, the Abwehr. Through pillow talk, Madame Szymanski relayed word to the Allies of German military moves into Russia, and the news of anti-Hitler plotting among his generals.

Working covertly in Swiss territory was not an easy task for Dulles. He tried hard not to interfere with the daily workings of the Swiss intelligence service, the Buro H, and did all in his power to lessen the profiles of his own agents. To that effect, he met on a regular basis with three of the most important men in Swiss Intelligence: Brigadier General Roger Mason, the bureau’s director, and his assistants, Captain Hans Haussamann and Major Max Waibel. The Swiss provided Dulles with such vital information as naming the anti-Hitler plotters among the Führer’s top staff, and discussed with him the actions of the Red Orchestra, the successful anti-German spy network run by the Soviet Union during the war.

Another of Dulles’s espionage coups during his first days in Bern was the close relationship he began with the French Resistance inside Switzerland. Dulles made a deal with the head of French Intelligence in Switzerland, Major Gaston Pourchot, who made available over 250 of his most experienced agents who had previously been active in both France and Germany. Newly de-classified OSS records tell that the United States provided up to 45,000 francs per month to support Pourchot’s agents.

As time went on, Dulles’s secret organization in Switzerland began to take root. His covert associations with both the French Resistance and the Swiss authorities opened many avenues that had previously been off limits. However, his most difficult task was getting agents into Germany. To that end, he recruited a German Standard Oil executive named Gero von Schulze Gaevernitz. Dulles was friendly with the younger Gaevernitz’s father, who had once served as a cabinet member in the old Weimar government. Gero Gaevernitz, 44 years old when the war began, was anti-Nazi in his politics and had offered his services to the British who declined.

Gaevernitz worked closely with another anti-Hitler activist named Elizabeth Wiskemann who was a member of a radical, anti-German group called the Kreisau Circle. The Kreisau Circle was made up of intellectuals, diplomats, and members of the old German nobility opposed to Hitler’s rule. Their goal was to remove Hitler from power by any means necessary (assassination was considered an option). Both Gaevernitz and Wiskemann were then living in Zurich, and Dulles made repeated trips to meet with them in late 1942. In time, Dulles was able to recruit Gaevernitz into the OSS, and he stayed on the American payroll until the war’s end.

Gero Gaevernitz was not high in the OSS pecking order, but he had access to other, more important people who the OSS might be interested in. In 1943, Gaevernitz introduced Dulles to a man who would play a huge role in penetrating the German Intelligence apparatus, Hans Bernd Gisevius.

Gisevius was the Abwehr voice in Zurich and a covert member of the Black Orchestra or Schwarze Kapelle, an anti-Hitler organization which included prominent members of the German diplomatic corps. Gisevius first entered the German intelligence service in the dreaded Gestapo under Heinrich Himmler but soon transferred to the Abwehr. Gisevius soon soured on Hitler’s regime and was sent by his boss, Admiral Wilhelm Canaris, the head of the Abwehr, who was also part of the Black Orchestra, to act as the liaison officer to the various resistance groups.

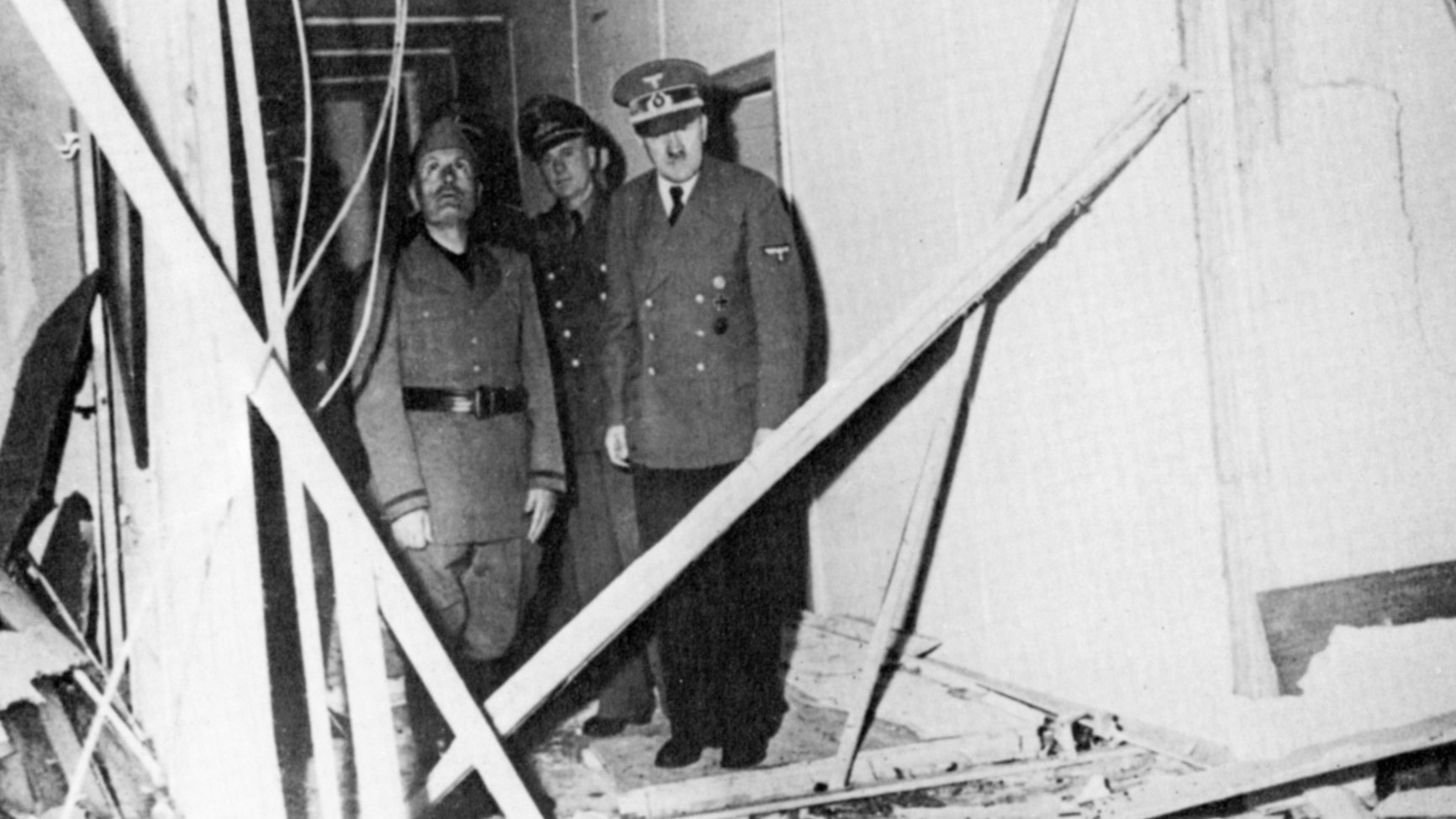

Dulles first met Gisevius in 1943 at the World Council of Churches building in Bern. Before approaching the OSS, Gisevius made contact with the British who thought he was a plant, out to sew disinformation among them. They refused his entreaties, and the wily German soon found a home with Dulles and the OSS. Gisevius proved to be a gold mine for the Allies as he gave them the locations of the powerful German V-1 and V-2 terror weapon launch sites. He was also an active member in the abortive plot led by Count Klaus von Stauffenberg to assassinate Hitler on July 20, 1944.

Dulles used his aide and lover, Mary Bancroft, as his official contact with Gisevius. After the war ended, Bancroft helped Gisevius write his memoirs. In a bit of gossip, he told Bancroft that there might have been a “relationship” between Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich, head of the powerful SD or Sicherheitsdeinst, the intelligence gathering component of the SS.

On April 6, 1944, Dulles reported to Washington about a conversation he had with Gisevius, who had just returned from Germany. He reported that German General Ludwig Beck and his associates were contemplating a coup against Hitler and were seeking Western help. However, Washington refused to participate in the coup, still seeking unconditional surrender from Germany, which had been stated Allied policy.

Another player in the Bern network was a young Austrian, an ex-soldier in the German Army, named Fritz Molden. Molden told Dulles that both his parents were part of the Austrian Underground that fought the Nazis. After being arrested by the Gestapo, Molden made a daring escape and wound up in Switzerland. He too had offered his services to the British but was turned away. Instead, he volunteered to spy for the United States in whatever capacity was needed. Molden worked tirelessly in building up a solid relationship between the Austrian Resistance and the OSS in Switzerland. After the war ended, Molden married Joan Dulles, his old spymaster’s daughter.

As can be seen in his recruitment of Hans Gisevius, Gero Gaevernitz, and Fritz Molden, Dulles was steadily broadening his anti-Hitler intelligence base in Bern. Each man added a little to the overall picture of events then unfolding inside Germany. Dulles’s next recruit was a man who would become an intelligence bonanza to the OSS and provide a window into Hitler’s headquarters previously unavailable. That man was a German diplomat named Fritz Kolbe.

At 42, Kolbe worked for German Ambassador Karl Ritter. Ritter was one of the most important agents receiving intelligence from Berlin. It was Kolbe’s job to read Ritter’s missives and write reports for the ambassador. Kolbe saw all the intelligence reports that came across Ritter’s desk, and he was a walking encyclopedia of information about the Nazis’ military plans.

Kolbe offered to work for British Intelligence in Bern but was rebuffed as a possible German plant. Kolbe was introduced to Gerald Mayer at the U.S. Office of War Information, and Mayer passed along Kolbe’s offer to Dulles. A secret meeting between Dulles and Kolbe was arranged at Dulles’s 23 Herrengasse home.

Without solicitation from Dulles, Kolbe offered up the diplomatic information that crossed his desk. He once carried to Dulles a briefcase with 186 documents smuggled from Ambassador Ritter, known in OSS parlance as the Bern Report. The information concerned a plan to rescue a captured German agent in Dublin, and, most important, the report that the Germans had cracked the U.S. cipher system.

The British checked Kolbe’s information for authenticity using the Ultra system. Claude Dansey, the second in command of MI-6, and Kim Philby, head of the Iberian Section of MI-6 (and a secret Russian agent), told Dulles that Kolbe’s material was fake. It was not, and Dansey had to reconcile himself to the fact that the British had passed on the services of one of the most important double agents of the war. Dulles, meanwhile, accepted Koble’s offer to commit treason against Germany. Dulles gave Kolbe the code name George Wood.

In a cable to OSS headquarters, Dulles wrote about Kolbe, “I now firmly believe in the good faith of Wood and I am ready to stake my reputation on the fact that these documents are genuine.” In subsequent visits to Dulles, Kolbe exposed the Abwehr’s secrets. Dulles sent the information dubbed Kappa to both London and Washington for their review.

In March 1945, one month before the war in Europe ended, Kolbe was allowed to stay permanently in Switzerland. By the time his double agent work concluded, Kolbe had given Dulles about 1,600 articles concerning Germany’s top diplomatic and military secrets. After the war, he disappeared among the countless men and women determined to begin a new life.

After the war in Europe ended, Dulles returned to the United States and resumed his old job as a powerful attorney with Sullivan and Cromwell. But as the Cold War against the Soviet Union began to heat up, he lobbied hard for a national intelligence agency for the new era. In April 1947, he testified before a Senate committee looking into the possibilities of forming a new intelligence agency and said that the West had to face the new Soviet threat by all means, technological and strategic. He hoped that he would be the leader of the newly created CIA, which was established in 1947 via the National Security Act inaugurated by President Harry S. Truman.

Dulles got his chance in 1953, when the newly elected President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him as the director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Dulles would stay in that post until 1961, when he was fired by President John F. Kennedy following the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba. During his tenure as CIA director, Dulles used the CIA to oust the regimes of Arbenz in Guatemala and Mossadegh in Iran, plan the attempted overthrow of Cuba’s Fidel Castro, and expand the top secret U-2 surveillance flights over the Soviet Union.

During his retirement in Washington, Dulles wrote books on intelligence, including Great True Spy Stories, Great Spy Stories From Fiction, and The Craft of Intelligence. He died in 1969.

Peter Kross, of New Brunswick, N. J., is the author of the books Spies, Traitors and Moles: An Espionage and Intelligence Quiz Book and The Encyclopedia of World War II Spies.

That was very interesting.