By Major General Michael Reynolds

In January 12, 1945, Adolf Hitler received the news he had been dreading—the Soviet Red Army had launched its winter offensive. He wasted no time. Within four days Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, commander in chief West, received the following order: “CinC West is to withdraw the following formations from operations [they were still involved in the Battle of the Bulge] immediately and refit them: I SS Panzer Corps with 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte and 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend; II SS Panzer Corps with 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich and 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen. Last day of refitting is 30th January. Reinforcements will be provided under the authority of the SS Supreme Operations Office.” These elite formations were to be reinforced and reequipped to lead another great offensive—this time on the Eastern Front. Hitler viewed the threat from the East as far more serious than that posed by the Western Allies, and he was determined to protect his Greater German Reich from Stalin’s “sub-humans.” The fact that the Battle of the Bulge had frittered away many of the men and much of the equipment needed to throw back and destroy the Soviet armies now threatening Germany was of no consequence, and he sent his personal adjutant, SS Major Otto Günsche, to the commander of the Sixth Panzer Army, General Sepp Dietrich, to tell him that within four weeks his army, comprising I and II SS Panzer Corps, would be moved to the Eastern Front to launch a new offensive, code-named Operation Spring Awakening. (Read more about these and other infamous military operations of Nazi Germany inside WWII History magazine.)

The Role of Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army with Operation Spring Awakening

Spring Awakening was designed to secure the vital oil deposits in southern Hungary and perhaps even regain the oil fields of Romania. Both Dietrich and General Heinz Guderian, the Army chief of staff, had wanted the Sixth Panzer Army deployed behind the Oder River to protect Berlin and northern Germany, but Hitler would have none of it. The only natural oil deposits in German-controlled territory were those around Nagykanizsa in southern Hungary and, with Allied air attacks disrupting and often neutralizing the synthetic gasoline production sites for long periods, it was essential to protect them. Without this crude oil the war could not be continued. Dietrich and the trusted divisions of the Waffen SS were to be given responsibility for Spring Awakening.

It proved impossible to fully refit Dietrich’s divisions by January 30; personnel and material replacements continued to arrive during the loading for the move to the east, during the move itself, and even after arrival in Hungary. Indeed, in view of the massive, and by now almost continuous, Allied air onslaught, the general state of the German war economy and not least, the appalling casualty rate sustained in five and a half years of war, it is astounding that Dietrich’s formation was made ready for an offensive action at all in such a short time, actually less than a month. Men were drafted from the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine, the slightly wounded and sick returned to their parent formations, and vehicles and tanks were delivered directly from factories.

Extraordinary measures were taken to conceal the fact that the Sixth Panzer Army was being moved to the Eastern Front. All ranks were ordered to remove their sleeve bands, and special code names were given to all components. Thus, II SS Panzer Corps became SS Training Staff South, the Das Reich Division was Training Group North, and the Hohenstaufen became Training Group South. Even regiments were redesignated as construction teams. For example, Der Führer became Otto North, after its commander, Otto Weidinger. Other deceptive measures included unloading part of the Sixth Panzer Army staff near Berlin and making it known that their final destination was in the Frankfurt-am-Oder area and, despite the air threat, actually sending the Tiger IIs of I SS Panzer Corps via the Berlin area before routing them through Vienna to Hungary.

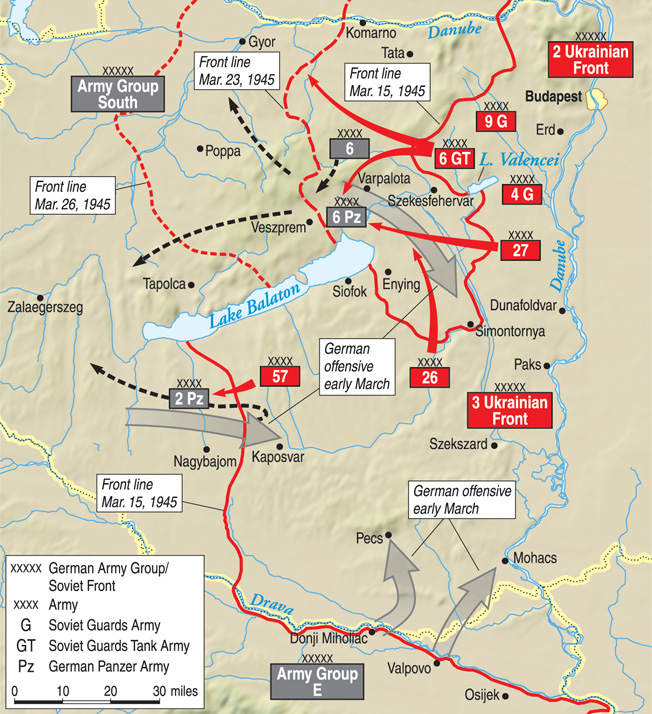

In view of the time needed to refit and move the Sixth Panzer Army to the Eastern Front and to secure the ground west of the Danube for the new offensive, Hitler ordered a preliminary attack in Hungary on January 18. This attack was designed primarily to cut off and destroy all Soviet troops north of a line drawn from Lake Balaton through Székesfehérvar (known to the Germans as Stuhlweissenburg) to Budapest, and secondly to liberate that city—the Pest garrison had in fact withdrawn across the Danube to the hills of Buda the night before.

400km Recaptured

Since the Russians had depleted their defenses in this area to meet previous German attacks in the north, this new offensive was initially very successful. Within three days, a large section of the west bank of the Danube had been secured south of Budapest, and the Germans then turned north and northwest, threatening to link up with other forces attacking in the north and to cut off an entire Soviet Front. By the 26th, however, with their forces in the south only 20 kilometers from Buda and in the north only half that distance, the Germans were exhausted. This was the moment when Soviet Marshal Rodion Malinovsky went over to the attack. Although Székesfehérvar and the ground between it and Lake Balaton were held by February 3, the Germans were more or less back to their original positions.

Meanwhile, Marshal Georgi Zhukov’s and Marshal Ivan Konev’s offensives in the north had advanced over 150 kilometers. Warsaw, Lodz, and Cracow had fallen, and a Soviet Army had entered East Prussia. The Red Army was now a mere 200 kilometers from Prague and, worst of all for the German people, it had crossed the Oder River and was only 70 kilometers from Berlin. This then was the crisis situation into which the Sixth Panzer Army was about to be launched.

Another factor complicating Hitler’s plan was that by mid-February 1945, the Red Army was holding a considerable bridgehead in Hungary across the Gran River north of Esztergom. This bridgehead was seen by the Germans as a potential assembly area for a major thrust toward Vienna and as such it had to be eliminated before the Germans could launch Spring Awakening. This preliminary operation was given the code name South Wind, and on February 13, Headquarters Army Group South ordered the commander of the German Eighth Army “to attack, concentrating all available infantry and armored forces, and accepting the consequent weakening of other front sectors, with the newly arrived I SS Panzer Corps…. After a short artillery preparation, to thrust from the north, to destroy the enemy in the Gran bridgehead.”

Operation South Wind proved a brilliant success. In eight days Hermann Priess’s I SS Panzer Corps, with valuable assistance from Panzer Corps Feldherrnhalle, recaptured over 400 square kilometers of territory, inflicted 8,800 casualties on the Red Army, and cleared seven infantry divisions and a Guards Mechanized Corps (equivalent to a German Panzer division) from west of the Gran—all for the loss of only 2,989 casualties. However, although it is remarkable that such an effective fighting machine could have been produced within a month of the Ardennes disaster, the more so when one takes into account that many of the men involved had received only minimal training, the question arises as to whether this elite SS Panzer Corps should have been used in this operation at all.

Six Divisions For the Sixth Army

Despite all the measures taken to disguise the arrival of the Sixth Panzer Army on the Hungarian front, units of I SS Panzer Corps were soon detected in the Gran bridgehead operation. Its commitment there, rather than in the northern part of the Eastern Front, and the knowledge that yet another SS Panzer Corps had arrived in Hungary immediately alerted the Soviets to the possibility of a German offensive. It is also obvious that the premature use of the Corps interrupted the proper refitting of its two SS Panzer Divisions and actually ensured that their effectiveness in Spring Awakening would be reduced. Taken together, these facts indicate that the use of I SS Panzer Corps in Operation South Wind was a serious mistake.

Hitler’s precise aims for Operation Spring Awakening were as wildly ambitious as those in the Ardennes three months earlier. They were to destroy the Soviet forces in the region bounded by Lake Balaton and the Danube and Drava Rivers, secure the Hungarian oil deposits, and establish bridgeheads over the Danube with a view to further offensive operations.

The attack was to be carried out in the north by Sepp Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army and the III Panzer Corps of Hermann Balck’s Sixth Army, and in the south, between the Drava River and the southwest corner of Lake Balaton, by the Second Panzer Army, part of Army Group Southeast and a panzer army in name only.

Serious concerns were expressed by Sepp Dietrich and his senior staff officers that as the Sixth Panzer Army and III Panzer Corps moved southeast and east they would become increasing vulnerable to any counteroffensive launched by the Soviet forces already located north of Székesfehérvar and west of the Danube. These comprised a Soviet army of three rifle corps backed by a guards mechanized corps. Since Balck’s Sixth Army defenses in this area were woefully inadequate, these concerns were fully justified. Nevertheless, Hitler rejected a proposal that these Soviet forces should be dealt with first or at least engaged, and the date of Spring Awakening was confirmed as March 6.

For its premier role in this final German offensive, the Sixth Panzer Army was reinforced to a strength of six divisions: the Leibstandarte and Hitlerjugend, Das Reich and Hohenstaufen, and the I Cavalry Corps with the 3rd and 4th Cavalry Divisions. The latter were genuine mounted troops and were a considerable asset in the conditions of the Eastern Front where the horse sometimes had advantages over motorized transport.

Facing the Second and Third Ukrainian Fronts

While the Germans were preparing Spring Awakening, the Soviets were planning their own offensive that was due to start on March 15. It was designed to capture Vienna and be carried out by the Second and Third Ukrainian Fronts (Army Groups) with four armies. Although the Soviets learned of the impending German offensive during the Gran bridgehead fighting, the Supreme Soviet Headquarters in Moscow decreed that two of the Russian armies due to take part in the Vienna offensive were to continue their preparations and were not to be included in any defensive planning.

Since the main German threat was known to be in the Third Ukrainian Front sector, the Soviets concentrated the bulk of their forces between Lake Balaton and a point some 20 kilometers to the north of Székesfehérvar. Here Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin massed three armies together with two tank corps and a guards mechanized corps. According to the Soviet official history, his forces totalled 407,000 men, 6,890 guns and mortars, 407 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 965 aircraft, but it is likely that many of his formations were much weaker than these figures suggest.

The Third Ukrainian Front commander reasoned that if and when the Germans attacked they would be sufficiently weakened by the depth of his defenses for him to launch his own offensive as originally planned, using the reserve armies and any forces unaffected by the fighting.

German intelligence of the Soviet defenses was good. Although it failed to identify the correct designation and exact positioning of every formation, it estimated the number of armies, corps, and divisions in the attack area with remarkable accuracy. Its only serious errors were in not detecting a guards mechanized corps and a guards cavalry corps in the path of the Sixth Panzer Army, and the positions of two of the three corps of Tolbukhin’s second echelon army astride the Danube.

To the north of the Third Ukrainian Front, Marshal Malinovsky’s Second Ukrainian Front numbered some 500,000 men and another 600 tanks, but over 400 of these were in reserve for the forthcoming offensive.

The primary component of the Spring Awakening offensive can be narrowed down to the area between Lakes Balaton and Valencei. There the attack involved Sepp Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army and the III Panzer Corps of the Sixth Army, with some 300 tanks and Sturmgeschutze self-propelled assault guns. These forces were opposed by more than 1,200 guns and mortars and, in theory but in the event not in practice, by some 300 Soviet tanks and assault guns.

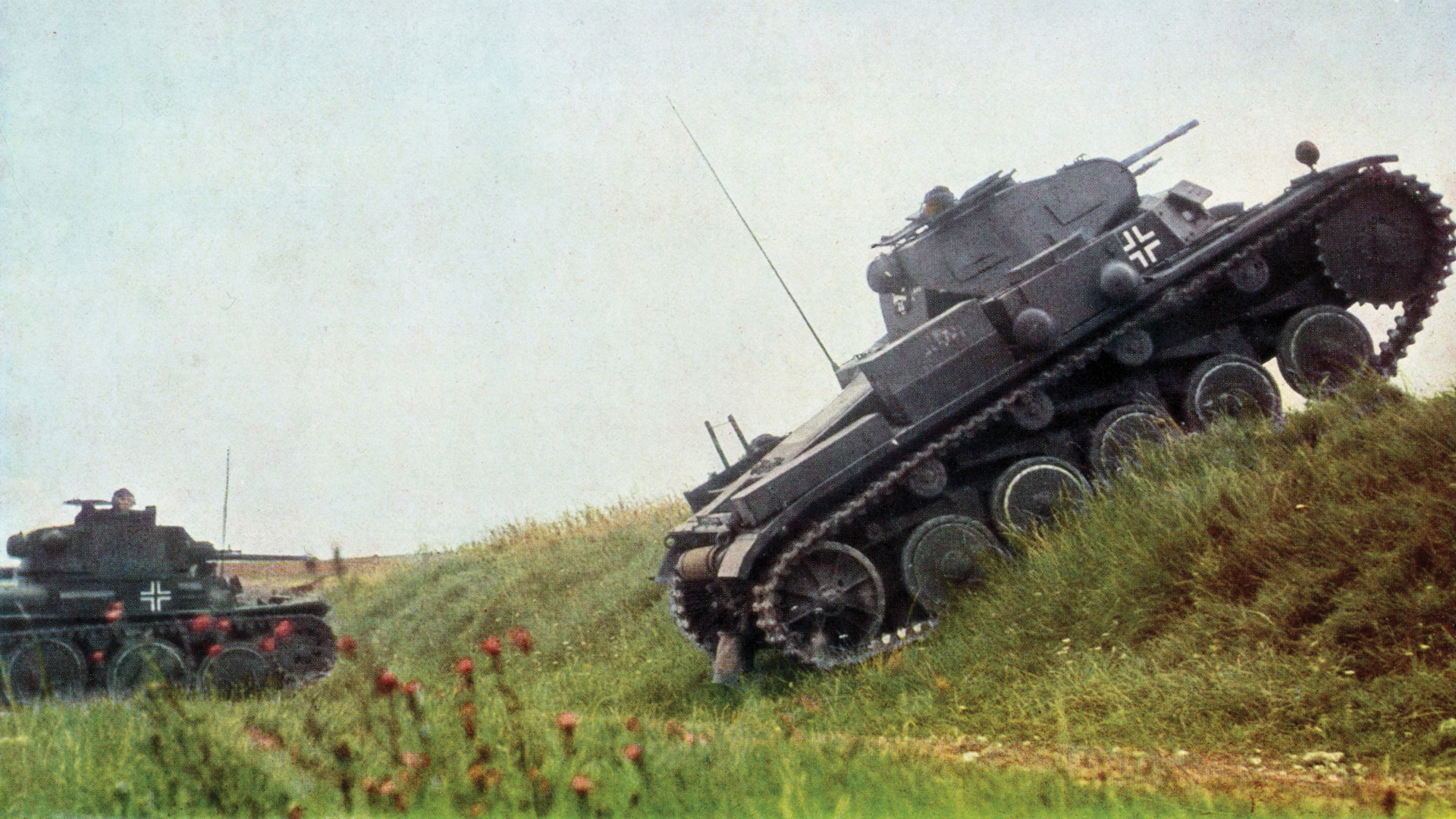

The state of the ground caused great anxiety in the German command. At the end of February the weather had become unexpectedly warm, and as the ground thawed all movement became difficult and cross-country movement, even by tracked vehicles, virtually impossible. The onset of what is called razputitza, a three- to four-week period of almost complete immobility in spring and autumn due to muddy conditions, did not augur well for Hitler’s last offensive.

Dietrich’s chief operations officer reported, “In the constricted area between Lakes Balaton and Valencei the mud became alarming. The closer one came to the … assembly area, the more widespread the land that was under water—impassable for all kinds of vehicles. It looked the same … in the enemy area, as far as the terrain permitted observation.… A Panzer attack in open terrain under these conditions is out of the question.”

As a result of this report, a request was made to Headquarters Army Group South that the attack should be postponed for at least two days, and Dietrich himself asked General Guderian in Berlin to support the proposal—to no avail.

An Advance Through Rivers of Mud

The II SS Panzer Corps’ final assembly area was just to the south of Székesfehérvar and its initial mission was to establish a bridgehead over the Danube between Dunaujvaros and Dunaföldvar, some 60 kilometers away. Das Reich and Hohenstaufen were to attack side by side on a 10-kilometer frontage, from a start line running due west from Seregélyes. The initial objectives were Sarkeresztur and Sarosd, both about 10 kilometers from the start line. The III Panzer Corps was tasked with screening the corps’ left flank, and its boundary with I SS Panzer Corps was the Sarviz canal, which together with the adjacent Sarviz River formed a major obstacle. On the right of I SS was I Cavalry Corps. The objective of these two corps was the Sio canal between Mezökomarom and Simontornya, 15 and 25 kilometers away respectively.

Units of Balck’s Sixth Army were manning the forward defenses in front of these assault forces and would come under command as the attack developed. A panzer division, the armored element of another, and a motorized brigade were held in Army Group South Reserve.

The area over which the Waffen SS divisions were to advance, although very open, is gently rolling country with a number of significant hill features and ridges. There were only two hard surface roads running southeast from Székesfehérvar, and even these had been turned into rivers of mud by the thaw. Had the ground been frozen at the time of the attack, the initial results might well have been very different.

23 Tank Killing Grounds

The Soviet defenses between Lakes Balaton and Valencei were constructed in great depth—on average some 30 kilometers. Seven infantry divisions were holding the front line between the lakes and four more, one of which was in Army reserve, were sited in depth between Sarbogard, Mezökomarom, and the southeast edge of Lake Balaton. Two of the frontline divisions were to the east of Lake Balaton, immediately in front of I Cavalry Corps, two faced I SS Panzer Corps, two more were opposite II SS Panzer Corps, and a divisional equivalent was in front of III Panzer Corps. The XVIII Tank Corps, with about 75 tanks and armored assault guns, provided a mobile reserve in the area of Sarosd, directly in the path of II SS Panzer Corps, and four more rifle divisions and a guards mechanized corps were situated just to the west of the Danube directly covering II SS Panzer Corps’ objectives of Dunaujvaros and Dunaföldvar.

As if all this was not enough to contend with, the Soviets had a further 12 rifle divisions within 30 kilometers of the east bank of the Danube and three more between the west bank and Lake Valencei. When one considers that the normal ratio expected for a successful attack is three to one in favor of the attacker, it becomes clear that the Sixth Panzer Army in general, and II SS Panzer Corps in particular, had been given formidable tasks.

A detailed Russian study of the Lake Balaton offensive gives full details of the strength and dispositions of one of the divisions forming the Soviet defense, the 233rd Rifle Division. This particular division was opposing the Hitlerjügend and part of the Leibstandarte, but the divisions facing the Das Reich and the Hohenstaufen divisions would have been similar in strength and deployment.

The study says that between February 18 and March 3 the 233rd Rifle Division had dug 27 kilometers of trenches, 130 gun and mortar positions, 113 dugouts, 70 command posts and observation points, and laid 4,249 antitank and 5,058 antipersonnel mines, all this on a frontage of 5 kilometers. It goes on to quote a figure of 114 guns and mortars, including six 122mm howitzers and 33 120mm mortars for the division, giving an average of 22 guns and mortars per kilometer of front, with up to 67 able to fire on the most important axes. Although there were no tanks in this defensive zone, there was an average of 17 antitank guns per kilometer forming 23 tank killing grounds.

The division was deployed with two regiments forward and a third on a flank in depth. This latter regiment was given counterattack tasks into what the divisional commander considered to be three areas of vital ground. The defenses were made up of three zones. The first, 1 to 1.5 kilometers deep, comprised two continuous trench lines and parts of a third. Some 1.5 to two kilometers farther back was another position made up of one continuous and one intermittent trench and then, three to five kilometers from the frontline lay a final trench line and strongpoint.

In terms of personnel strength, the study claims that on March 6 the division was 70 percent below its authorized strength and that its regiments, with an average strength of only 665 men, had therefore been reduced to two instead of three battalions. This may well be true, but just as the Germans sometimes exaggerated their losses in order that the actions of the survivors might appear more heroic, so it is more than likely that the real divisional strength was in fact higher, at least in the region of 40 percent of authorized establishment or, in other words, nearer 5,000 than the 3,500 quoted. The whole study is written in the heroic style.

The Führer Order to Attack

On March 2, General Wilhelm Bittrich’s II SS Panzer Corps was placed on an alert status and told to be prepared to move. All training was immediately suspended. The following day, its divisions, Das Reich and the Hohenstaufen, were ordered forward to their final assembly areas for the new offensive, south and southeast of Székesfehérvar. By first light on the 4th, Das Reich, after moving through Györ and Zirc, had reached the Varpalota area while the Hohenstaufen, following a route through Kisbér, was in the region of Mor.

It seems that detailed orders for the attack were not received until around midday on the 5th—only 16 hours before H-hour and when the leading grenadiers were still over 20 kilometers away from their final jumping-off points. A lack of cover and clogged routes meant that most of the transport vehicles had to be left well to the north and the men had to complete this march carrying their full equipment and combat loads of ammunition.

To compound this already desperate situation, the routes they had to take and share through Székesfehérvar with III Panzer Corps were a morass of mud. Then, to compound the whole problem, as darkness fell it began to snow. There was no possibility of either division’s tanks or heavy equipment reaching the forward assembly areas in time for the attack. Complaints by both divisional commanders and the corps chief of staff that there was no possibility of II SS Panzer Corps being ready at H-hour were to no avail. Bittrich was not empowered to authorize a delay or postponement and Dietrich’s appeal to Guderian had already been rejected. The attack order was a Führer Order, and that was that.

Priess’s I SS Panzer Corps was more fortunate. Although it faced similar problems, it had its route through Polgardi to itself, and it reached its forward assembly area southeast of that town in time for H-hour.

As dawn broke on March 6, snow was still falling from low cloud and the temperature hovered around zero degrees Celsius. The ground was frozen near the surface, and men and vehicles sank into thick mud the moment they moved off the few roads available. Conditions were very similar to those experienced in the Ardennes only three months earlier.

While it is generally agreed that the 30-minute artillery barrage heralding the beginning of Spring Awakening began as planned at 4 am on March 6, there is considerable disagreement as to exactly when the II SS Panzer Corps attack began. From all the available evidence it seems clear that the corps did not in fact launch any serious attacks on the 6th. However, I SS Panzer Corps launched its attack on time, but even then surprise was not achieved and the gains were small—the deepest penetration being a mere four kilometers. Farther to the west, the 3rd and 4th Cavalry Divisions were forced back to their start lines by Soviet counterattacks.

A Bogged Down Advance

On the eastern flank there was some success. By midday, units of III Panzer Corps had advanced about four kilometers to the east, south of Lake Valencei, and penetrated into Seregélyes. This threatened the rear of the Soviet defense zone in the XXX Corps area, causing alarm within the Soviet command. The reaction was swift. Marshal Tolbukhin reinforced Lt. Gen.Gagyen, the Twenty-Sixth Army commander, with two tank brigades and three antitank regiments from his reserve XVIII Tank Corps, and Gagyen ordered these units to take up positions confronting III Panzer and II SS Panzer Corps. Gagyen also placed his reserve rifle division under the command of the XXX Corps. Finally on this day, Tolbukhin ordered a division from his reserve army into a second defensive line opposite II SS Panzer Corps; a complete rifle corps from east of the Danube to move to a new position to the south of Simontornya; and two tank regiments of I Guards Mechanized Corps to begin moving west toward Sarbogard.

The following day, March 7, II SS Panzer Corps attacked soon after first light. The Hohenstaufen advanced toward Sarosd in rain mixed with light snow. The entire landscape was a morass of mud, and it was soon clear that it would be impossible to launch the division’s panzer regiment. Two tanks disappeared in mud up to their turrets, and the rest of the lead company had to stay on the only hard surface road in the attack zone. The SS Panzergrenadiers, struggling forward on their feet, were therefore without effective armored support. To complicate matters, long-range Soviet artillery was interdicting the bulk of the Hohenstaufen’s armor still crossing the Sarviz canal at Szabadbattyan.

The attack reached a high point about five kilometers northwest of Sarosd but then bogged down. The Das Reich attack was no more successful. Again, the supporting tanks were mired and the grenadiers could make only limited progress on their own against the well-prepared Soviet field fortifications. Unfortunately for II SS Panzer Corps, the Russian XXX Corps commander had correctly identified the roads leading southeast out of Székesfehérvar as the most likely enemy axes and had deployed his strength accordingly.

On the right of II SS Panzer Corps’ zone, the 44th Panzergrenadier Division “Hoch und Deutschmeister” managed to advance four kilometers to a hamlet northeast of Aba, but again Soviet countermoves were decisive. Another rifle division and a tank brigade were allotted to XXX Corps, and the division that had come under command the previous day took up positions facing west along the Sarviz canal north of Sarbogard.

The Army Group South War Diary for March 7 reads, “II SS Panzer Corps, which did not get going yesterday because of a delayed arrival, today, primarily with infantry forces, drove a 6km deep wedge into the main enemy defenses as far as the hills west of Sarosd.”

The I SS Panzer Corps was more successful. The Soviet study of the Balaton offensive confirms that by 8 pm on the 7th the Leibstandarte had breached the second-line defenses of the 68th Guards Division on a five-kilometer front, and this caused the division to withdraw behind the Sarviz canal where the Army’s reserve rifle division had already taken up defensive positions. This move began at 1 am on the 8th and, according to the study, despite German efforts to disrupt the withdrawal, the division was dug in on the east bank by last light.

German Success on the 9th

On March 8, I SS Panzer Corps’ attack gained momentum, and by evening Nagy had been secured against minimal opposition, as had the Enying–Dég road about three kilometers west of Dég. The II SS Panzer Corps’ Hohenstaufen, however, failed to get beyond the Aba–Sarosd road. A motorized rifle brigade had reinforced the hard-pressed infantry division in this sector, and the only real success came just after dark when some fortified farmsteads were captured to the northwest of Sarosd. The Soviets claim that the other division of the corps, Das Reich, made nine separate attacks on this day but again “antitank and artillery fire from concealed positions stopped the enemy attack.”

The failure of II SS Panzer Corps to make progress on the east side of the Sarviz canal was inevitably causing deep concern at Headquarters Army Group South and Sixth Panzer Army and this led, on the night of the 8th, to the release of the 23rd Panzer Division from the Army Group South reserve to I SS Panzer Corps. With some 50 tanks, Jagdpanzers, and Sturmgeschützes, the division was ordered to follow behind the Leibstandarte and to be prepared to cross the Sarviz canal and attack the Soviet forces in the rear of the II SS Panzer Corps in the Sarkeresztur area.

The situation began to change dramatically on March 9. In I SS Panzer Corps’ sector one Kampfgruppe (battlegroup) of the Leibstandarte overcame well-defended positions covering the Nagy–Saregres road to the north of Saregres before being brought to a halt by an antitank screen immediately north of the village. Another, in spite of the unfavorable ground conditions, reached the high ground 2.5 kilometers north of Simontornya before being halted by dug-in antitank guns and heavy artillery fire from positions south of the Sio canal. In the Hitlerjugend sector things also went reasonably well, particularly when one considers that there were no roads and few negotiable tracks in its area. Dég was soon captured, and by evening the division’s leading elements were immediately to the north of Mezöszilas.

On the right flank of I SS Panzer Corps, one division of I Cavalry Corps exploited the gap created by the Hitlerjugend and reached the main road between Enying and Mezökomarom, while the other attacked Enying.

The Russians viewed the events of March 9 with some alarm. As the Frunze Military Academy Study describes it: “From the morning of 9 March, the operational situation on the XXX Rifle Corps front [opposite II SS Panzer Corps] sharply deteriorated. The success of the enemy in breaking through the tactical defence zone of CXXXV Corps [on the I SS Panzer Corps front] created a serious threat to the rear of the Twenty-Sixth Army.… Because of this breach, control between the two left hand Corps of the Army and XXX Rifle Corps became too complicated, so CinC Front [Tolbukhin] ordered XXX Rifle Corps transferred to the Twenty-Seventh Army.”

This transfer was part of an overall restructuring of the Third Ukrainian Front. From the night of the 9th Tolbukhin’s reserve Twenty-Seventh Army became responsible for the sector between Lake Valencei and the Sarviz canal. Meanwhile, General Gagyen’s Twenty-xixth Army remained responsible for halting what Tolbukhin considered the main threat: I SS Panzer Corps and I Cavalry Corps between the Sarviz canal and Lake Balaton. To this end Gagyen was reinforced with a tank regiment, a self-propelled artillery brigade and two anti-tank regiments, and the main weight of the Third Ukrainian Front’s close air support effort was retargeted to his sector.

Preparing the Counteroffensive

While the 9th had been a good day for the men of I SS Panzer Corps on the west side of the Sarviz canal, Dietrich and his senior commanders were acutely aware that the left flank of the corps was becoming dangerously exposed. The II SS Panzer Corps still had not reached Sarkeresztur and only the difficulties of crossing the Sarviz River and canal were preventing the Russians from attacking the flank of the German penetration. Marshal Tolbukhin, however, was not slow to recognize the operational opportunities offered by this situation, and on the same day he requested the release of one reserve army to his control and the use of another. Moscow refused, saying that these armies were earmarked for the forthcoming general offensive and that he would have to make do with what he had.

In fact, the Supreme Soviet Command went further and, on this same day gave both Tolbukhin and Malinovsky revised missions. The Third Ukrainian Front was to continue to defend south of Lake Balaton with two armies but was to be prepared to launch a major attack north of Lake Valencei with two reserve armies, one of which Tolbukhin had just requested. The aim of this attack was, as Dietrich had feared, to strike the rear of the Sixth Panzer Army. Malinovsky’s Second Ukrainian Front was to join in the attack after one or two days, with two armies attacking westward along the south bank of the Danube. Later, the armies north of the Danube and south of Lake Balaton were to join in the offensive. The initial attack by Tolbukhin was to be made as soon as the Sixth Panzer Army’s offensive had been halted. This was expected to be on the 15th or 16th.

The strength of the Soviet position derived from their early knowledge of the forthcoming German offensive and their ability to formulate and develop an overall strategy to deal with it both before and during the fighting. The fact that they were facing reverses in one area did not distract them from their long-term aim, and the albeit serious situation on the west side of the Sarviz was seen as an opportunity rather than as a setback. The similarities between the Balaton offensive, the Mortain counterattack in Normandy, and the Battle of the Bulge are obvious—the difference being that the Americans had no prior warning and had to react to events rather than preplan them.

“Fighting Continued at Night”

On March 10, the terrible weather and ground conditions ensured that progress west of the Sarviz was slow. The Hitlerjugend continued its painful advance toward Ozora and, after capturing Mezöszilas by 9 pm, moved on during the night to capture Igar, four kilometers northwest of Simontornya. In the sector of I Cavalry Corps, the 3rd Cavalry Division managed to seize a bridgehead over the Sio, five kilometers west of Mezökomarom, and the 4th Division encircled Enying.

On the same day, the 23rd Panzer Division, despite heavy antitank and artillery fire from the east side of the Sarviz canal, closed up to Saregres. By nightfall it had taken over from the Leibstandarte on that flank and this allowed the SS division to concentrate for its attack on Simontornya and the subsequent crossing of the Sio canal. The I SS Panzer Corps was now some 25 kilometers ahead of II SS Panzer Corps, and the threat of a Soviet counterattack into its exposed flank appeared ever more likely.

The appalling ground and weather conditions and stiff Soviet resistance prevented any further progress in the II SS Panzer Corps sector on the 10th. The Soviet Study says: “Cruel fighting took place around Hill 159 where artillery played a significant role in the destruction of the enemy. Unable to achieve success with frontal attacks, the enemy tried to outflank the objective; however, this maneuver was frustrated by tanks and SP guns in enfiladed ambush positions. Fighting continued at night.”

The lack of progress by Bittrich’s corps is hardly surprising. Apart from the adverse ground and weather conditions, II SS Panzer Corps was now up against the major part of six infantry divisions (with two more sited in depth farther east), albeit most of them seriously understrength, and significant elements of two armored formations. Nevertheless, on the 11th Das Reich launched an attack described by General Otto Weidinger, the overall commander, as “right out of the textbook.” It was successful and by mid-morning had reached an important hamlet lying six kilometers southeast of Sarkeresztur known as Heinrich Major. At the same time, on the right flank a vineyard immediately northeast of Sarkeresztur was captured, effectively cutting off Aba.

On the same day, I SS Panzer Corps had even more success. Panzergrenadiers of the Leibstandarte spent the day clearing the important ridge lying just to the north of Simontornya, and at the same time the Hitlerjugend captured the road junction 1,500 meters south of Igar. This secured the jumping-off positions for the final attack on Simontornya, which was to be carried out the following day. Meanwhile, on I SS Panzer Corps’ left flank the 23rd Panzer Division penetrated into Saregres but was unable to clear it. Army Group South’s hopes of launching an attack across the Sarviz in this area in support of II SS Panzer Corps were proving overly optimistic.

German Armor Losing Momentum

March 12 saw the status quo more or less continue on II SS Panzer Corps’ front. The only real success seems to have occurred at Aba, which was cleared by the 44th Panzergrenadier Division. The attack in the Heinrich Major area was continued but cost several tanks and self-propelled guns. Later in the day, two Soviet counterattacks were repulsed, the second being supported by 10 tanks, four of which were claimed destroyed.

The Leibstandarte’s attack on the town of Simontornya on March 12 was launched from the high ground north of the Sio canal. Fierce house-to-house fighting lasted all day, but by last light Simontornya north of the Sio was largely in German hands with only a few pockets of resistance remaining.

Another somewhat surprising success on the 12th came in the I Cavalry Corps’ sector, where the 3rd Cavalry Division managed to cross the Sio canal and secure a bridgehead to the west of Mezökomarom while the 4th Cavalry Division closed up to Balatonszabadi. Nevertheless, despite these gains there was little doubt that the Sixth Panzer Army’s offensive was losing its momentum. The II SS Panzer Corps had been decisively halted, and Priess’s Corps was now up against five infantry divisions backed by a cavalry corps. The fact that these divisions were understrength was relatively unimportant, for the ground they were holding was ideal for defense and totally unsuitable for an attacking armored formation.

Undetected by German intelligence, the buildup for the forthcoming Soviet offensive was proceeding rapidly on the 12th. The movement of the Sixth Guards Tank Army with some 500 tanks to an assembly area just west of Budapest was completed, and a second attack army was moving in behind the army defending the sector immediately to the north of Lake Valencei. The scene was being set for the final destruction of the Sixth Panzer Army.

Fighting Off Soviet Counterattacks

From March 13-15, II SS Panzer Corps remained in a defensive posture with the Hohenstaufen still in front of Sarosd and Das Reich in a half circle around Sarkeresztur. The Deutschland Regiment and elements of the 44th Panzergrenadier Division were just to the north of the small town, and the armored group continued to beat off repeated attacks on its positions at Heinrich Major. Numerous requests to withdraw from this exposed salient, less than three kilometers wide, were rejected.

The 14th was mainly sunny, and the temperature climbed, drying the ground. On the 15th, Das Reich continued to beat off repeated Soviet counterattacks. Strength returns on this day show the Hohenstaufen with 35 Panther tanks, 20 Mk IVs, 32 Jagdpanzers, 25 Sturm-geschützes and 220 other self-propelled weapons and armored cars. Forty-two percent of these vehicles were, however, under short- or long-term repair. Das Reich had 27 Panthers, 22 Mk IVs, 28 Jagdpanzers and 26 Sturm-geschützes on hand. Figures for self-propelled weapons, armored cars, and vehicles under repair are not available.

The most surprising thing about these figures is that the Hohenstaufen had six Panthers and eight MK IVs more than when it started the offensive and was only two Jagdpanzers and one Sturmgeschütze worse off, and Das Reich was down only seven Panthers, two Mk IVs, one Jagdpanzer, three Sturmgeschützes, and 38 armored cars and self-propelled weapons—the latter despite the fighting at Heinrich Major. Two things are clear from these figures. First, the repair and resupply system was working well, and second, the appalling ground conditions had prevented the deployment of the majority of the armored vehicles.

What of the more successful I SS Panzer Corps during this period? The Leibstandarte’s small bridgehead across the Sio canal at Simontornya was successfully defended throughout the 13th. There were numerous Soviet counterattacks, all supported by tanks and aircraft. Meanwhile, the 23rd Panzer Division had managed to clear Saregres on the Sarviz River, but a subsequent attempt to force a crossing of the canal near Cece failed in the face of tenacious resistance. This ended Army Group South’s hopes of supporting II SS Panzer Corps’ advance with attacks from west of the Sarviz.

The Sixth Army Withdraws

While the Sixth Panzer Army persisted in its efforts to implement the basic strategy of Operation Spring Awakening, the Soviet preparations for their own offensive were nearing completion. In addition to the Sixth Guards Tank Army already assembled just west of Budapest, another 24 rifle divisions, a tank corps, and a guards mechanized corps were being made ready for the strike across the rear of Sepp Dietrich’s command.

On March 14, the bridge across the Sio in Simontornya laid by the Leibstandarte’s SS Pioneers was badly damaged by Soviet artillery fire and the Corps’ armor and heavy weapons were forced to remain on the north bank. Nevertheless, during the afternoon SS Panzergrenadiers managed to expand the Simontornya bridgehead to some five square kilometers.

Meanwhile, the Soviets were attempting to establish their own bridgehead across the Sarviz canal in the Saregres sector and at Ozora, and it was these Soviet counterattacks that were seen by all the senior German commanders as ominous signs of things to come. At army group and army level, German intelligence had detected part of the Soviet buildup on the 13th, but the moves had been misinterpreted as local reinforcements, and it was not until the evening of the 14th that the Army Group South War Dairy recorded: “Today’s movements leave no doubt of the enemy’s intentions. Based on the results from aerial observation, motorized columns of at least 3,000 vehicles are moving out of the rear area from Budapest … to the southwest, most of them in the direction of Zamoly. His objective will be to cut the rear connections of the German forces [Sixth Panzer Army and III Panzer Corps] which have advanced from the narrow passage of Székesfehérvar, by an attack in the direction of Lake Balaton.”

During March 15, I SS Panzer Corps continued to hold its slender bridgehead across the Sio, but it was now clear to most German commanders that Spring Awakening had failed. Sepp Dietrich recommended an immediate withdrawal to a suitable defensive line in the north, but this was ruled out by his superior, General Otto Wöhler, the commander of Army Group South. At 3:10 pm, the latter gave his assessment of the situation to Berlin. He pointed out that any attempt to advance farther south in the I SS Panzer Corps area would be “inexpedient” owing to the hilly terrain and the corps’ exposed left flank.

This was a major understatement. The ground to the south was not only hilly, it was broken, wooded, and bounded on both sides by waterways—something that should have been foreseen when the original plan was made. Wöhler proposed, therefore, to leave the 23rd Panzer Division where it was in the Saregres sector and, after relieving I SS Panzer Corps on the Sio with I Cavalry Corps and a Hungarian Division, to move it north to a position behind II SS Panzer Corps and III Panzer Corps. All three panzer corps would then attack east, between Sarkeresztur and Gardony, toward the Danube before turning south in accordance with the original plan. Wöhler estimated it would take four days to complete the necessary regrouping. Berlin approved this plan, which was hardly surprising since it was both strategically and tactically superior to the original concept, but demanded that it be put into effect in three days, not four.

Although this revised concept was considered impracticable by most of the field commanders involved, the necessary orders were issued at 11 pm, and during the night the first units of I SS Panzer Corps were withdrawn from the battle area.

The End of Operation Spring Awakening

On March 16, as I SS Panzer Corps made its first withdrawals from the Simontornya bridgehead, two Soviet Armies launched a major attack on a 20-kilometer front in the IV SS Panzer Corps sector between Székesfehérvar and the Vertes hills. Behind them stood the Sixth Guards Tank Army, and on their northern flank another army waited to join in the offensive. The immediate Soviet objectives were Tata and Györ in the north and Varpalota and Veszprem in the south. The southern thrust was designed to cut off and destroy Dietrich’s Sixth Panzer Army.

Unbelievably, as late as 11 pm on the same day, General Wöhler still believed he could implement his plan to attack east with his three panzer corps, and that same night Headquarters Sixth Panzer Army issued orders for the relief of I SS Panzer Corps during the following two nights. At 1:20 am on the 17th, however, General Guderian, Army chief of staff, recommended to Wöhler’s chief of staff that preparations be put in hand for I SS Panzer Corps to attack north rather than east—into the flank of the Soviet advance. At 1:45 am, in spite of Hitler’s refusal to allow any changes to his master plan or any major redeployments without his personal permission, the Chief of Staff Army Group South, Lt. Gen. von Grolmann, instructed Dietrich to prepare I SS Panzer Corps for just such an attack. Later that morning, Wöhler finally requested permission from Berlin to use I SS Panzer Corps for the attack from the Varpalota area toward Zamoly. This was followed by another request for authority to withdraw II SS Panzer Corps behind I SS Panzer Corps as soon as it arrived in the vicinity of Székesfehérvar.

Bittrich’s corps had continued to defend its Aba–Sarkeresztur sector during this period and was now dangerously exposed. Hitler eventually gave his permission for these deployments at 1:40 am on March 18, and at 2 am. Wöhler ordered Dietrich to move I SS Panzer Corps to the area north of Varpalota and subordinate it to Army Group Balck.

So ended Hitler’s last offensive action of World War II. Just over seven weeks later the surviving men of these once elite corps would be prisoners of war—but not of the Soviets—of the Americans.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments