By Charles Whiting

On the morning of Monday, December 18, 1944, a mixed group of white MPs and black American service troops stood guard on the little bridge at Aywaille in the Ardennes Forest of Belgium. Two days before, the Germans had attacked some 20 miles away and had broken through the American front virtually everywhere.

Now rumors abounded on all sides. The Germans had dropped paratroopers; German saboteurs were cutting American landlines way beyond the front. It was even said that German commandos were trying to free prisoners of war in faraway England. Understandably, this mixed group of American was nervous and apprehensive. About noon, a jeep containing three men in American uniform slowly approached the roadblock. Dutifully, the jeep began to slow down as the men at the barrier raised their weapons and one of the MPs stepped out into the middle of the road, hand upraised, carbine still slung across his back.

The jeep driver braked, there was a small exchange in English, and then the MP asked for the password. The driver paled and stuttered something. “The password, buddy!” the MP rasped threateningly, as the black soldiers stared at the jeep’s three occupants with sudden interest. The jeep driver blustered something about not having been given a password. That was enough for the MP. Each man in the Liège area who was traveling that day had been given a password before leaving his outfit. He indicated that the three soldiers in the jeep should get out—slowly.

No Ordinary GIs

Swiftly the identities of these three Americans who did not know the password were established. They were Pfc. Charles W. Lawrence, Pfc. George Sensenback, and Pfc. Clarence van der Werth. Nothing very special about that. Now the black soldiers began to examine the jeep, and almost immediately it was discovered that these were no ordinary GIs, for in the gear hidden under the seat they found a huge roll of hundred dollar bills as fresh as the day they had come off the printing presses. This was not surprising as they had been printed the week before in a secret German concentration camp forgery plant!

For a little while, the searchers suspected that they had apprehended a group of deserters or black marketeers, since the three did speak excellent English. Soon, however, the MPs searched the interior of the jeep and found two British Sten machine pistols, two Colt pistols, two German Walther pistols, plastic explosive, a radio transmitter, six American hand grenades, and most incriminating of all, cigarette lighters containing poison, the L (for “lethal”) pill.

The smallest of the three started talking. His real name was not George Sensenbach, but Wilhelm Schmidt, and he was a corporal in the German Army! It was the sensation of the day. The American soldiers crowded around him as he explained how he and the other two had set off from Monschau in Germany on December 12. Some days later, they related, they had successfully penetrated the U.S. lines, posing as members of the 5th U.S. Armored Division. Their mission was “infiltrating through the Americans and reporting the condition of the Meuse bridges and of the roads leading to those bridges.”

The Americans did not wait to hear any more. They raced for the field phones and got in contact with Liège headquarters. There were gasps of excitement at the other end. More Kraut infiltrators! They had to be everywhere! Within 30 minutes, a fleet of jeeps crammed with heavily armed MPs and members of American field intelligence, the CIC, were on their way to interrogate the three ashen-faced Germans, who had less than a week to live. They were later taken to the little Belgian township of Henri-Chapelle, a matter of miles away from the homeland they would never see again, tied to stakes, and shot to death as spies.

Schmidt, who had been one of the first volunteers to join an organization run by the notorious SS commando Otto Skorzeny, he told his impatient interrogators, “Early in November 1944, I reported to an SS camp at Friedenthal where I was examined as to my linguistic ability by a board consisting of an SS officer, a Luftwaffe and a naval officer. I passed the test but was ordered to refresh my English. For this purpose, I spent three weeks at American prisoner of war camps where a large number of American war troops were imprisoned.” Schmidt had the CIC men sitting on the edges of their seats, for he now told how the engineers in his group had the task of “destroying headquarters and headquarters personnel.”

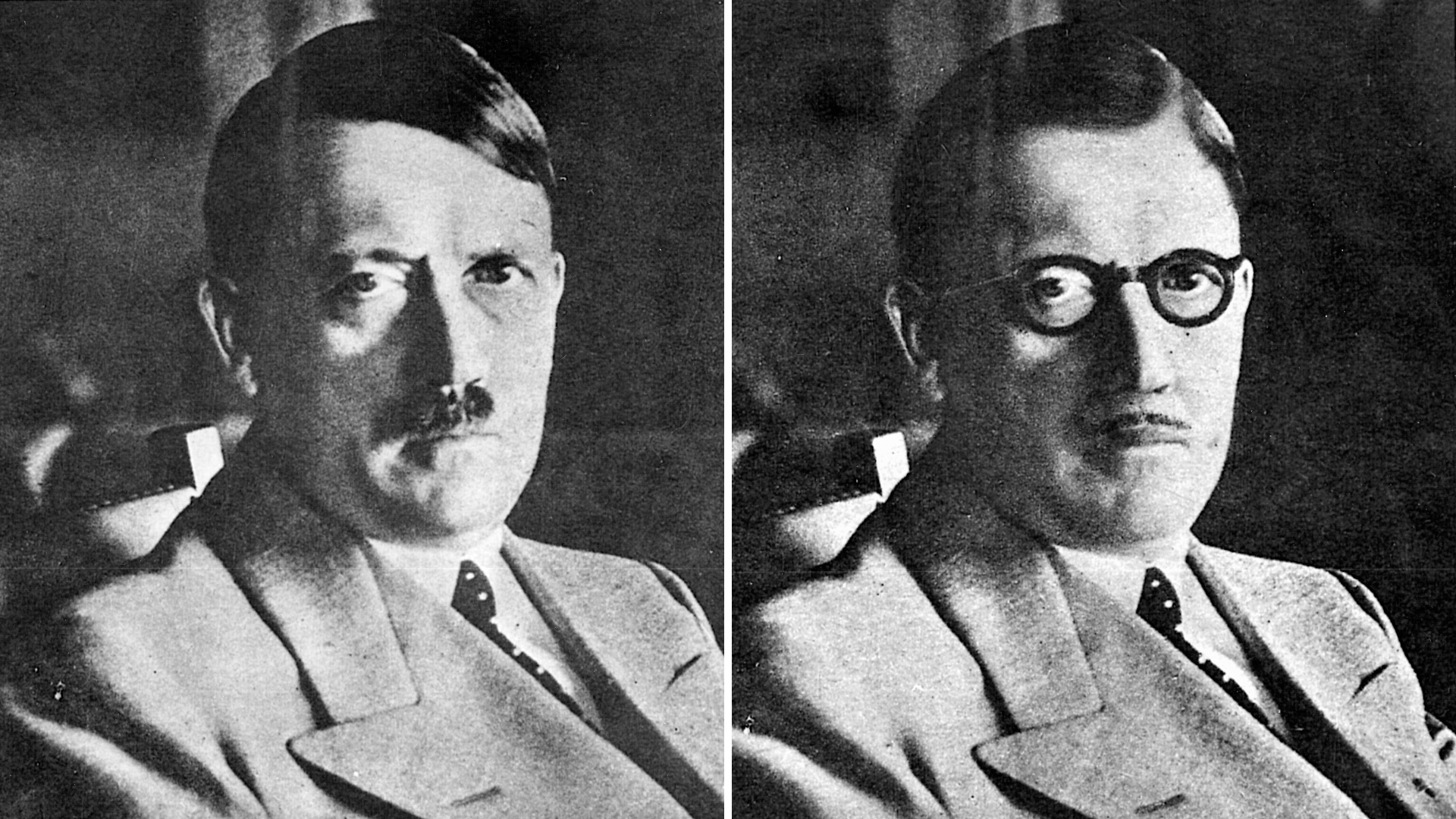

Orders to Kill General Dwight D. Eisenhower?

“What headquarters and what headquarters personnel?” the CIC wanted to know. Now it all came out, those wild rumors that had run the rounds of Skorzeny’s Gräfenwohr Training Camp the month before: their dash across France disguised as German POWs to break into the port of Lorient, the surprise attack on Montgomery’s headquarters in Holland, the column of “captured” Tiger tanks that would meet up with the assassins assembling at the Café de la Paix, Paris.

“To do what?” the CIC agents undoubtedly asked excitedly. The answer: “To kill … General … Eisenhower!” At the Allies’ lavish Versailles headquarters where it was said that each of Eisenhower’s most important 26 aides had double that number of personal aides themselves, most people had been worrying not about the Germans, but about the imminent approach of Christmas. There was one exception: a minor staff officer named Lt. Col. Gordon Sheen, who was the chief of the U.S. Corps of Counter-Intelligence (CIC) in Europe.

Sheen and his organization were virtually unknown at the Versailles headquarters. He and his agents were shadowy figures fighting to survive in the multitude of intelligence organizations dominated by the CIA’s forerunner, the OSS.

Besides, Sheen and his men had a bad strike against them. They had incurred the wrath of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Sheen, in particular, had probably only been saved from being sacked by his posting overseas to England, and then North Africa. Apparently, the CIC had bugged a room occupied by Staff Sergeant Joseph Lash, an Air Corps noncom who was a personal friend of both Eleanor and Franklin Roosevelt.

According to a report dated December 31, 1943, and later submitted to the president, a sexual encounter between Eleanor and the NCO had taken place in the hotel room. As the story goes, when the information was passed on to Roosevelt, he understandably fell into a towering rage. He ordered Lash overseas within 10 hours. After Lash, a suspected communist as well as a seducer, the CIC agents followed, also being sent overseas.

Whatever the truth of the matter, the CIC virtually ceased to exist in the United States. Those senior agents who had survived the Washington “bloodbath” were undoubtedly happy to be overseas and out of FDR’s striking range. Sheen must have thought the same, especially when he was appointed to SHAEF. Now the most senior officer of CIC in Europe, he reported directly to General Kenneth Strong, the head of Eisenhower’s intelligence group in Europe. Strong was not particularly interested in counterintelligence (at least not yet) and left the rounding up of spies, informers, sleeper agents, and so on, to lesser people.

Naturally, Sheen had to produce results to justify his position or he might well find himself back in the nation’s capital, which might prove fatal to his military career. He knew he would not impress a high-ranking intelligence expert such as Strong by arresting a few sleeper agents—and plenty of them had gone underground in Paris. Instead, he concentrated on protecting Eisenhower himself, something that would make the authorities aware of his lowly presence in a great headquarters where “half colonels were a dime a dozen.”

Soldiers Began to Apprehend Germans Dressed as Americans

According to Paris CIC records and those of CIC units attached to Army and Corps headquarters throughout the U.S. Twelfth and Sixth Army Groups, German troops disguised in American uniforms had begun infiltrating U.S. lines as early as August 1944. In some cases they were also driving captured U.S. jeeps. No one was able to ascertain their purpose and as far as the CIC was concerned these disguised Germans, sometimes aided by renegade Frenchmen as guides, did not belong to any overall plan. Their activities seemed to have been directed by local commanders. In addition, they were scattered all along the long Allied front, so in the end no great importance was attached to them. However, a CIC commander did note that “six German commandos” had been apprehended in American uniform that August.

By November, things had become more serious and Sheen started to worry. On the 15th, he received a report from a subordinate attached to General Jacob Devers’ Sixth Army Group headquarters in France. It stated that a company of the 15th Engineers engaged in frontline road repairs had been surprised by an attack force of some 70 Germans, yelling for reasons known only to themselves, “GI!”

All of these Germans had been dressed in American uniforms. Sheen would have been even more worried if he had known that the attack was a dress rehearsal for Operation Northwind, the second stage of the Battle of the Bulge due to start in Alsace on January 1, 1945.

In the same week, the first of a trickle of German prisoners, who would all repeat the same alarming story, told Sheen’s interrogators that he had seen a secret order from his headquarters requesting that all English-speaking personnel be sent to Osnabruck in northern Germany. There, according to the German POW, there English-speaking German soldiers would be given special training in reconnaissance and sabotage.

Sheen was aware of General Wilhelm Keitel’s request that personnel with the ability to speak “American” English and pass as GIs report to Skorzeny’s headquarters at Friedenthal. It did not take too much mental effort to realize that these four Germans captured in American uniforms in Aywaille were up to no good. More importantly, they belonged to an organization run by that notorious SS commander Skorzeny.

On the basis of Skorzeny’s past record between 1943-1944, Sheen did not need a crystal ball to realize that Skorzeny was going to use these men in some long-range operation behind the front. Knowing as much as he did of Skorzeny’s choice of high-ranking targets—“the Big Three,” Mussolini, Horthy’s son, Tito—this might well mean that the scar-faced Austrian was after an Allied “big fish.” In Sheen’s case, the only big fish who mattered in the Paris district was Eisenhower.

The Hangman’s Dilemma

It is not known at this stage whether Sheen communicated his fears and suspicions to General Strong that first week of December. From all accounts, there seems to have been no noticeable tightening of security at Versailles. At the best of times, security at Supreme Headquarters, staffed by personnel from a dozen different Allied countries ranging from America to New Zealand, appears to have been quite lax. However, Major Noel Annan, who worked on Strong’s intelligence staff, felt that it was “the Hangman’s Dilemma” as to who was to “blame for an episode that turned drama into farce,” one that would soon see Sheen “burst into a room at SHAEF headquarters at the Hotel Trianon, crying, “Skorzeny is driving on Paris!”

Strong, who was chinless, was known to his subordinates as “the Hangman’s Dilemma” because the noose would slip if it ever came to Strong’s hanging. Now the scares spread from Supreme Allied Headquarters at Versailles to Paris itself. A rigorous curfew was in force. The capital was put out of bounds to all GIs on leave. Suddenly, the Place Pigalle (“Pig Alley” to GIs on leave) was deserted of its lounging doughboys and the French tarts in their rabbit fur jackets and cork- heeled wedge shoes. The only Americans seen on the streets were grim-faced security men searching for the would-be killers hired by Skorzeny, the man whom the Americans labeled “public enemy No.1.”

Spies, saboteurs, killers, and para-agents were spotted everywhere. Hundreds of innocent American soldiers were arrested because guards or sentries didn’t like the look of them or they did not give the “right” answer when challenged.

For example, on the morning of December 20, big bluff Brig. Gen. Bruce Clark, in the midst of a last-ditch defense of the town of St. Vith with what was left of the 7th Armored Division, was “arrested” by American military policemen. Over and over he repeated, “But I’m General Bruce Clarke of the CCB (Combat Command B).” “Like hell!” the MPs snarled cynically. “You’re one of Skorzeny’s men. We were told to watch out for a Kraut posing as a one-star general.”

While Clark raged, knowing that the vital rail and road head of St. Vith might well be lost while he was in jail, the MPs kept him in custody for five long hours. In the end, the MPs released him and one of them had the audacity to ask for his autograph. Nonplussed, Clarke gave it to him. Clarke was not the only senior officer to be stopped. His commander, General Omar Bradley, recalled later, “Three times I was ordered to prove my identity by cautious GIs. The first time by identifying Springfield as the capital of Illinois (my questioner held out for Chicago); the second time by locating the guard between the center and tackle on a line of scrimmage; the third time by naming the then current spouse of a blonde named Betty Grable. Grable stopped me, but the sentry did not. Pleased at having stumped me, he nevertheless passed me on.”

“A Half Million GIs Played Cat and Mouse with Each Other”

British Field Marshal Bernard L. Montgomery was another victim. In despair, he pleaded with General William H. Simpson of the U.S. Ninth Army to provide him with American identity documents so that he could go about his business of trying to reestablish the front in the north.

As General Omar Bradley commented, “A half million GIs played cat and mouse with each other each time they met on the road. Neither rank nor credentials spared the traveller an inquisition at each intersection he passed.” On all sides, American tried to trick American. Soldiers on the road would find themselves stopped and a tommy-gun thrust menacingly through the frosted window of their jeep or truck, with a hoarse voice demanding, “Okay, buddy, who’s dem bums?….Who is Pruneface? …. Where does Li’l Abner live? … Who works with Jiggs?”

Others, knowing the Germans’ difficulty with the letters “R” and “W,” tried out intricate tongue-twisters on the suspect, using those letters, “Rotund Rosie runs round rugged rocks ….William wilted visibly when Vera whipped off her woollies,” and the like. By now, however, Skorzeny, the scar-faced “public enemy No.1,” had disobeyed Hitler’s orders. He had crossed the front line and had seen action in Belgium. At Ligneuville near the scene of the Malmedy Massacre, where nearly a hundred U.S. POWs had been shot by SS men, he was seriously wounded in the eye and was sent back to the Reich for treatment. His part in this alleged assassination of General Eisenhower was over, but did he really intend to have General Eisenhower assassinated?

In May 1945, Skorzeny surrendered to the Americans. At first, no one was interested in him until Colonel Sheen of the CIC heard of the arrest. Sheen immediately drove to southern Germany where Skorzeny was being held and grilled the Austrian for six long hours. Surprisingly, he used an alias telling Skorzeny that he was the head of U.S. 7th Army Intelligence, which was patently untrue. Why did he do this? After all, he was the man who had first caused the panic at Versailles by declaring, “Skorzeny is driving on Paris!” Now he reported to the press in an interview given to the U.S. Forces paper Stars and Stripes that there “had never been a German intention to attack General Eisenhower’s Headquarters.”

Was Sheen right? Was he really telling the truth? Or had Otto Skorzeny been blackmailed into stating that he had never intended to kill Ike because Sheen, along with many others who soon would form the CIA, wanted to use Skorzeny’s expertise in Russia to uncover the secrets of that new enemy?

An Enigmatic Answer to a Historical Enigma

What, in later years, did Otto Skorzeny himself report on this matter? Did he really intend to kill the head of Allied Forces in Europe? His past record, including the liberation of Mussolini, the attempted assassination of Tito, and the kidnapping of Admiral Horthy’s son to keep Hungary alllied with Germany showed that he was prepared to go to any measure to achieve victory for Nazi Germany.

With Ike out of the way, the Allied coalition might well have had to fight a much longer war until a new Allied leader was found who would satisfy both Britain and America. So the assassination of General Eisenhower would have achieved an important political and military victory for Germany.

Over 30 years ago, this writer met an ailing Otto Skorzeny at a secret rendezvous in Germany. It can now be disclosed that the location was Boberg Hospital near the city of Hamburg, Germany. He had come from his home in Madrid to have two tumors excised from his spine, surrounded by his old toughs, many of whom were obviously carrying weapons.

When asked if he had really intended to kill Ike, Skorzeny said “I shall not answer that directly, Herr Whiting. But you must believe this, if I had intended to kill Ike, I would have done so.” Then he smiled weakly. It was an enigmatic answer to a historical enigma.

I especially found this article of interest, as my father, Sam Dickey Jr., was at Henri-Chapelle and part of the firing squad that executed Schmidt and his two fellow Nazi soldiers. He was with the 509th MP Bn, and told me the story many times. His birthday was December 16th, and he remarked this wasn’t the birthday present he had hoped for!

Thank you.