By Michael D. Hull

After refueling in the mid-Atlantic and suffering bow damage from being rammed by a tanker, a 769-ton German submarine reached its destination, the American East Coast, early on Monday, May 4, 1942.

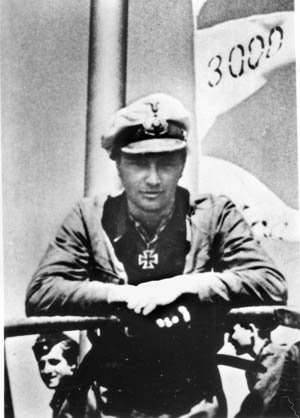

U-333 stayed submerged off the balmy southeastern Florida shore during the daylight hours and then surfaced when evening came. Climbing one after another to the bridge for a breath of fresh air, Lt. Cmdr. Peter Cremer and his 43 crewmen rubbed their eyes in disbelief.

“We had left a blacked-out Europe behind us,” reported Cremeer, one of Admiral Karl Dönitz’s bold “gray wolf” submarine skippers who wreaked havoc on Allied convoys throughout World War II. “Yet here the buoys were blinking as normal, the famous lighthouse at Jupiter Inlet was sweeping its luminous cone far over the sea. We were cruising off a brightly lit coastal road with darting headlights from innumerable cars.”

Laden with 14 torpedoes and mines, the Type VII submarine moved in so close to the Florida coastline, said Cremer, that “we could distinguish equally the big hotels and the cheap dives, and read the flickering neon signs…. All of this after nearly five months of war! Before this sea of light, against this footlight glare of a carefree new world, we were passing the silhouettes of ships recognizable in every detail and sharp as the outlines in a sales catalogue. Here they were formally presented to us on a plate: please help yourselves! All we had to do was press the button.”

Cremer’s first victim the following day was the 13,000-ton American tanker Java Arrow, followed by the unarmed 11,000-ton tanker Halsey and a smaller freighter. The U.S. submarine chaser PC-451 pursued U-333 without success. Meanwhile, the other U-boats nearby were enjoying an equally satisfactory second “Happy Time.” The first was in 1940, when the first wolfpack operations wreaked havoc on shipping around Great Britain.

“All Aid Short of War”

America had been at war for five months in May 1942, but her defenses still needed time to galvanize. The Pacific Fleet had been savaged at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, many warships were mothballed on the West Coast, and the Navy Department was slow to act. While the Eastern Seaboard was virtually unprotected during the first disastrous six months of 1942, the U-boats sank thousands of tons of Allied and neutral shipping from Newfoundland to the Caribbean. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill called it “a terrible massacre.”

Yet, although the East Coast was vulnerable, U.S. Navy ships had been on active duty in the Atlantic long before the Pearl Harbor attack. Hewing to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s policy of “all aid short of war,” the Navy Department and the British Admiralty had agreed that American ships would help escort North Atlantic convoys.

“The situation is obviously critical in the Atlantic,” declared Admiral Harold R. “Betty” Stark, chief of naval operations, on April 4, 1941. Roosevelt warned on May 27, “The war is approaching the brink of the Western Hemisphere itself. It is coming very close to home.”

U.S. Navy patrol bombers flew convoy coverage from Iceland and Newfoundland, and in July a U.S. Marine Corps contingent started relieving the British garrison in Iceland.

Bringing War to the American Coast

The shooting phase of America’s undeclared war began on September 4, when the destroyer USS Greer was attacked by a U-boat. Roosevelt denounced the “piracy” and ordered his ships to fire on any vessel that interfered with American shipping. First blood was drawn on the night of October 17, 1941, when the destroyer USS Kearny, escorting a slow convoy, was torpedoed. She made it back to port, but 11 of her crew were killed. Two weeks later, on October 31, the aging flushdeck destroyer USS Reuben James, also on convoy escort, was ripped apart by a U-boat’s torpedo. The death toll was 115, and the American people were shocked. Seven merchant ships, meanwhile, were sunk while the nation was still neutral.

When Japanese carrier planes swept over Pearl Harbor on the fateful morning of Sunday, December 7, 1941, thrusting a woefully unprepared United States into World War II, the Germans were as shocked as the Americans. General Hideki Tojo, the scrawny, owlish Japanese war minister, had not informed Adolf Hitler of his expansionist war plans in the Far East or about the strike on Pearl Harbor. The German high command was caught off guard, and no one was more surprised than U-boat chief Admiral Karl Dönitz.

Hitler had barred operations off the American coast and the sinking of U.S. warships, but Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, the German Navy chief, informed Dönitz on December 8, that the restrictions had been rescinded. Dönitz was anxious to extend operations to the Western Hemisphere. When Nazi Germany declared war on the United States on December 11, he introduced two new types of submarines, the 1,100-ton Long-range Type IX and the 1,700-ton “milch cow” tender, which would replenish U-boats far from their bases. Dönitz swiftly drew up plans to renew a campaign which, like the wolfpacks and surface night attacks, had been tried out in the last year of World War I.

After more than two years of devastating attacks on British shipping since September 1939, he intended to take the war to the American East Coast. Dönitz, himself a submarine veteran of World War I, wanted such an operation to prove more destructive than the imprudent blockade of the summer of 1918, when three U-boats sank the cruiser USS San Diego, damaged the battleship USS Minnesota, sank 28 steamers, and destroyed more than 50 small, unarmed tugs, barges, yachts, and motor boats. As the U.S. official history of the naval war noted later, “Admiral [Alfred von] Tirpitz’s coastal campaign of 1918 was a very faint taste of the foul dose that Admiral Dönitz administered in 1942.”

Dönitz asked Hitler for permission to divert a dozen long-range U-boats from the Mediterranean area and send them against the United States. He proposed to greet America’s entry into the war with “a roll of the drums.” But the Führer was unwilling to weaken the German and Italian forces in the Mediterranean, so he allowed Dönitz to divert only six boats.

At the time, Dönitz had under his command 91 submarines, of which 55 were available. Sixty percent of these were in dock being refitted or repaired, which left 25. Twenty-two were at sea, so this left only three boats at hand. The frustrated Dönitz, who had told Hitler in 1939 that he could starve the hated British into submission with a fleet of 300 U-boats, never had enough of them at his disposal. But he meant to make the most of those he had.

Operation Drumbeat

By December 1941, Dönitz was ready to commit five long-range U-boats to the long Atlantic voyage and six-week patrols off the American coast. The boats would be on station for two weeks. He called the five captains into his office and gave them their orders. Lieutenant Heinrich Bleichrodt, Lieutenant Ulrich Folkers, Lieutenant Reinhard Hardegan, Commander Ernst Kals, and Commander Richard Zapp were told not to attack shipping unless the target was more than 10,000 tons until they reached their assigned patrol areas. They were to stay out of sight of enemy forces and to make only surprise attacks.

Dönitz was sure that the American coastal defenses were fragmentary and disorganized, and he wanted the submarine skippers to use maximum shock tactics. They broke into grins when their chief told them that he dubbed the campaign Operation Paukenschlag, or “Kettledrum Beat.” The Allies would know it as Operation Drumbeat.

The U-boats were made ready in newly built concrete pens at Lorient and in the nearby Brittany fishing port of Keroman, on the Bay of Biscay in occupied France, in December 1941. The captains were told little about their mission. Supervising the cramming of a maximum supply of ammunition, food, fuel, and 15 torpedoes aboard his U-123, the tall, thin Hardegan reported, “We were given an envelope that we were only supposed to open after receiving a specific radio message. We were just told to make the U-boat ready for a long trip.” Additional space had to be made for a reporter from the Propaganda Ministry.

Launching on December 23

The first of five U-boats set off in the third week of December. Hardegan chose to get underway on December 23, not wanting to leave on Christmas Eve because his crewmen would probably be drunk and homesick. A large crowd gathered to cheer U-123’s departure on December 23. Soldiers from a nearby Army battalion presented the crew with a Christmas tree and a cake, short speeches were made, and tears were shed. Then, to the strains of the Nazi march “Sailing Against England,” the U-boat slipped her mooring lines and eased down the River Scorff and into the Bay of Biscay.

Submerged at a depth of 50 meters the following day, the U-123 crew celebrated Christmas. Lieutenant Hardegan read the Bethlehem story, carols were sung, weak punch was poured, presents from home were opened, and control room mechanic Richard Amstein played his accordion. Then the boat surfaced and headed westward. Beyond the Bay of Biscay, Hardegan made radio contact with Dönitz’s headquarters at the Chateau Kernevel near Lorient and was ordered to open his envelope.

The admiral had decided that the first wave of boats would operate between the St. Lawrence River in Canada and Cape Hatteras on the North Carolina coast. The five submarines were to reach their stations and await Dönitz’s final order to go into action simultaneously. Hardegan’s mission was to patrol off New York City, which he had visited as a naval cadet in 1933. When the destination was announced over the U-123 loudspeaker, Amstein reported, “A few of the crew wondered whether we would get back from there in one piece, but most of us were enthusiastic.”

The U-boats approached their assigned patrol areas early in January 1942. Dönitz planned to launch Operation Drumbeat on the 12th, but on January 2, he broke his own orders and authorized New York-bound U-123 to intercept a Greek steamer with a broken rudder drifting in thick fog 200 miles east of Newfoundland. Hardegan located the ship, but two Canadian destroyers lay in wait. The water was shallow, and the German skipper decided not to risk losing his boat. He withdrew and “felt very bad about it.” The U-boat was 300 miles off course and had wasted much fuel.

Hardegan was luckier on January 12, while he was off Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and still distant from his assigned area. Sailing alone, the 9,100-ton British steamer Cyclops was a target too tempting to pass up, so U-123 sank her with two torpedoes. All but two of the ship’s complement of 180 escaped, but 84 froze to death in her lifeboats. By the evening of January 14, Dönitz’s U-boats were on station, and Operation Drumbeat was underway.

Meeting No Resistance

The sinkings mounted swiftly. Commander Kals’s U-130 had dispatched the Norwegian steamer Frisco in the Gulf of St. Lawrence on January 13, and the Panamanian freighter Friar Rock in the same area eight hours later. Lieutenant Hardegan soon added to his grim score. Cruising 60 miles off Montauk Point, Long Island, on the morning of January 14, U-123 surfaced and sank the 9,600-ton tanker Norness.

That night, Hardegan boldly edged his boat into the outer reaches of New York Bay. “We could see the cars driving along the coast road, and I could even smell the woods,” reported watch officer Horst von Schroeter. Hardegan observed, “They simply weren’t prepared at all…. After all, there was a war on. I found a coast that was brightly lit. At Coney Island, there was a huge Ferris wheel and roundabouts —could see it all. Ships were sailing with navigation lights. All the light ships, Sandy Hook and the Ambrose lights, were shining brightly. To me this was incomprehensible.”

Unhindered and undetected close to the American coast, Dönitz’s gray wolves picked off their targets at leisure. Hardegan sank the tanker Coimbra on January 15 and the steamer San Jose on January 17. Commander Zapp’s U-66 dispatched the tanker Allan Jackson on January 18, followed by another tanker and three freighters. On January 19, Hardegan made more attacks in broad daylight, sinking three ships and damaging another. He had made a habit of lying on the ocean bottom during daylight hours but realized that this was unnecessary because the coastal defenses were nonexistent.

Hardegan’s fellow skippers continued the carnage. U-130 sank the tanker Alexander Hoegh south of Cape Breton, followed by two freighters and four more tankers. Zapp’s U-66 destroyed another tanker and three freighters, and Lieutenant Bleichrodt’s U-48 dispatched the Canadian tanker Montrolite and three freighters. Hardegan used his last torpedo against the tanker Malay off Cape May, New Jersey, on January 19, but the damaged vessel made it into port. On the voyage back to France, U-123 sank the 3,000-ton freighter Culebra with gunfire.

The first five U-boats to penetrate American waters returned to base after sinking 23 ships totaling 150,000 tons. Hardegan’s share was nine ships totaling 50,766 tons. Admiral Dönitz was pleased and signaled U-123, “To the Drumbeater Hardegan. Bravo. You beat the drum well.” Hardegan was awarded the coveted Knight’s Cross.

Back in Lorient, the skipper was able to confirm Dönitz’s belief that the American waters constituted a happy hunting ground and suggested that he step up the campaign and send minelayers. Dönitz had already dispatched more U-boats, and the sinkings continued, although he never had more than a dozen craft in action at one time along the American coast.

The Donald Duck Navy

Although there were some sightings of periscopes and rumors of an imminent invasion by enemy ships, most Americans were still in the dark about the underwater threat close to their eastern shores. But the British were aware by the end of January 1942 that the Germans had suddenly turned their major U-boat effort west. With one exception, convoys in the western approaches to Britain were now untouched. From Enigma intelligence decrypts, the submarine-tracking room at the Admiralty in London was following the gray wolves’ movements.

Information was passed to the U.S. Navy, but no serious action was taken. Blame for the woeful lack of preparedness on the Eastern Seaboard lay with Admiral Ernest J. King, commander of the U.S. Fleet and soon to be named chief of naval operations. Although he had his hands full with Japanese aggression in the Far East, he had been warned in December 1941 by Vice Admiral Adolphus “Dolly” Andrews, commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier, that “should enemy submarines operate off this coast, this command has no forces available to take adequate action against them, either offensively or defensively.”

The U.S. Navy had built no subchasers and lacked an antisubmarine flotilla. Most of its destroyers and other small craft were attached to the fleets or committed to oceanic convoy protection. Like the Royal Navy in 1939, the U.S. Navy had entered the war with an acute shortage of escort vessels. President Roosevelt commented that the Navy “couldn’t see any vessel under a thousand tons.”

The able, 62-year-old Andrews, a battleship veteran of World War I, had been trying to round up ships since December 7, but by early January he had available only 20 vessels and 103 aircraft, most of them obsolete, to guard the 1,500-mile coastline. His largest vessel was a 165-foot, 16-knot Coast Guard cutter, and the others were small tugs, yachts, trawlers, schooners, and motor cruisers. Admiral Andrews’s fleet was officially called the Coastal Picket Patrol, but many of the enthusiastic amateurs who served in it dubbed it the “Hooligan Navy.” Others called it the “Donald Duck Navy.” King’s response to Andrews’s appeal was to dispatch minelayers to mine the approaches to New York, Boston, Chesapeake Bay, and Portland, Maine.

The Cost of “Business and Pleasure as Usual”

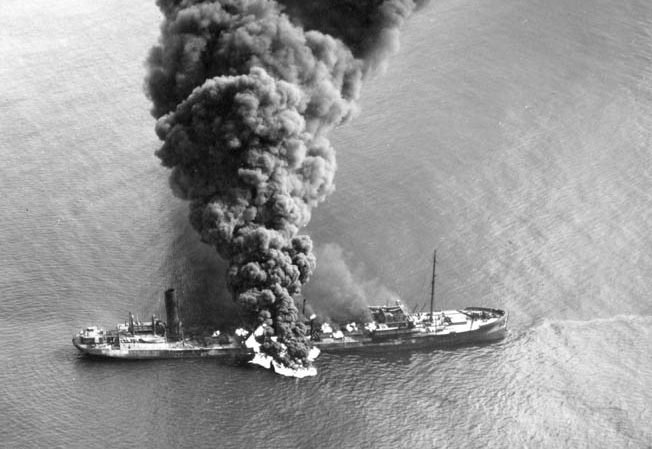

From the bleak Canadian coast and eventually to the balmy Caribbean, the U-boats roamed at will, sinking unescorted freighters and tankers with ease. They struck at night on the surface with both torpedoes and deck guns. Their hapless targets were virtual sitting ducks, etched sharply against the glare of New York, Atlantic City, Miami, and other coastal cities that refused to impose blackouts for fear of losing tourist trade.

The official history said later, “One of the most reprehensible failures on our part was the neglect of the local communities to dim their waterfront lights, or of military authorities to require them to do so, until three months after the submarine offensive started. When this obvious defense measure was first proposed, squawks went up all the way from Atlantic City to southern Florida that the ‘tourist season would be ruined.’ Miami and its luxurious suburbs threw up six miles of neon-light glow, against which the southbound shipping that hugged the reefs to avoid the Gulf Stream was silhouetted. Ships were sunk and seamen drowned in order that the citizenry might enjoy business and pleasure as usual.”

Ships were sunk 30 miles or less offshore, and sometimes three or more vessels went down in a day. Passengers landing at airports in the New York-New Jersey area saw flaming wrecks from their windows, and sunbathers along Virginia Beach watched two ships go down in front of them. Burning tankers became a familiar sight off some coastal resorts, and black oil seeped onto beaches.

“Our U-boats are operating close inshore along the coast of the United States of America” boasted Admiral Dönitz to a German reporter, “so that bathers and sometimes entire coastal cities are witnesses to the drama of war, whose visual climaxes are constituted by the red glorioles of blazing tankers.”

The German Propaganda Ministry was quick to report the U-boat attacks in American waters, and a photograph of the Manhattan skyscrapers taken from the conning tower of Hardegan’s submarine appeared in German newspapers long before the boat returned to base.

A Losing Battle Unreported

A brutal one-sided war was being waged on America’s doorstep, but the public was told a different story. Hardegan reported, “We listened to the American radio transmissions and we heard, ‘We have sunk a U-boat.’ We were supposed to have been sunk three times. Every time we sank a ship, we were sunk again. The Americans obviously needed this as a consolation—the idea that they had done something. But it wasn’t true.”

On November 17, 1941, Congress had amended the Neutrality Act of 1939, permitting merchant ships to be armed and to enter war zones. But most of the vessels sunk were unarmed. Hundreds of seamen had to stand by helplessly while their ships—many of them aged and rusting—were attacked with no means of fighting back. The vessels that were hastily armed were not much better off. One seaman reported, “That rust-pot I just came off, they must have got her out of the Smithsonian Institute [sic]. Sure, we had a gun on her. But, holy mackerel! If we’d ever of had to fire it, the whole ship would have fallen apart.”

Admiral Andrews was fighting a losing battle against the offshore raiders, which were averaging three kills a day. In mid-February, he had available nine protective vessels that could make 14 knots or better and another 19 that could run at 12-14 knots. Most of the U-boats could make 18 knots. Andrews had no antisubmarine aircraft available.

The only underwater predator sunk in the Atlantic that month was U-93, dispatched by the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Hesperus. Unable to cope with the losses off their coast, the Americans neither sank nor damaged any German submarines. By the end of February, 327,000 tons of shipping had gone down, most of the vessels off the Eastern Seaboard. Dönitz was elated and was able to send more boats to take station off the United States and in the South Atlantic and the Caribbean.

The campaign in the Caribbean escalated as half a dozen U-boats and several Italian submarines marauded with alarming temerity. On February 16, Lt. Cmdr. Werner Hartenstein’s U-156 slipped into the port of Aruba in the Dutch West Indies and torpedoed a tanker, damaged two others, and shelled the harbor installations. Three days later, U-161, commanded by Lieutenant Albrecht Achilles, entered the harbor at Port of Spain, Trinidad, and torpedoed an American freighter and a British tanker. Both sank at anchor. Other U-boats sank shipping, mostly tankers, off Port of Spain and in the Gulf of Venezuela.

King’s Resistance to the British Convoy System

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was alarmed at the mounting losses in American waters, and on February 6 he suggested to Harry L. Hopkins, Roosevelt’s trusted special envoy, that his chief give the crisis special attention. In a letter to Churchill, Roosevelt admitted that the Americans had a lot to learn but that he hoped to have an adequate patrol system working by May 1. Admiral Sir Dudley Pound, the British First Sea Lord, meanwhile, cabled Admiral King in Washington and suggested that the proven convoy system was the only way to defeat the U-boats. The Royal Navy had learned that patrols were not effective. Pound offered to help the Americans by lending 22 armed trawlers.

Churchill and the Admiralty pressed the convoy idea, but King was unreceptive. The bluff, Anglophobic King mistrusted Churchill and the British and did not relish heeding their advice. He told Pound tartly that a convoy system was under “continuous consideration.” King believed that ships sailing independently were less vulnerable than when bunched together in convoy without strong escort protection. But the British experience in World War I and in 1939-1941 had shown that a poorly escorted convoy was better than no convoy at all.

Churchill offered Roosevelt some Lend-Lease in reverse, 24 armed trawlers and 10 corvettes, with officers and crews experienced in antisubmarine warfare. “It was little enough, but the utmost we could spare,” said the prime minister. Roosevelt accepted, and the Royal Navy craft were on station by the end of February. These were the first effective weapons made available to Andrews.

Eventually, under pressure from Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, who told him, “The losses by submarines off our Atlantic seaboard and in the Caribbean now threaten our entire war effort,” Admiral King relented. The losses in merchant shipping and oil continued, and they were severe. Officials in Washington calculated that the sinking of a freighter’s cargo was equivalent to the loss of goods carried by four railroad trains with 75 cars each.

129 Tankers Sunk

Although the British were preoccupied with ground actions against the Germans and Italians in the Western Desert and East Africa, and with naval operations in the North Atlantic, the Mediterranean, the North Sea, and the English Channel, Churchill and the Admiralty kept a close watch on the continuing destruction of shipping along the American coast. U-boat movements were monitored, but there was little that Admiral Andrews’s motley patrol fleet could do in response. Churchill pressed the matter with Roosevelt and urged “drastic action.”

Admitting that the U.S. Navy had been “slack in preparing for this submarine war,” Roosevelt assured the British leader that every vessel over 80 feet long was being pressed into service, that there soon would be “a pretty good coastal patrol,” and that orders had been placed for the building of 60 antisubmarine ships.

The slaughter continued in March, with the tonnage sunk equaling that of January and February combined. At this rate, Admiral Andrews estimated that the U-boats would destroy two million tons of shipping in a year. On March 11, Churchill told Hopkins that unless America could provide escorts to stop the sinking of tankers in the Caribbean, he would have to prevent or delay sailings. Twenty-three tankers had gone down in February, and the Petroleum Industry War Council warned that if the situation did not improve, America would run out of oil in six months.

On the night of March 17, four tankers and a steamer in an unprotected convoy were torpedoed off Cape Hatteras by youthful Lt. Cmdr. Johann Mohr’s U-124. Andrews went to Washington to plead with Admiral King for help. He asked for destroyers. The Atlantic Fleet had 73, but only two were available to Andrews on a loan basis. King flatly refused, and Andrews agreed with Churchill that the sailing of tankers would have to be halted. After U-boats sank seven tankers in the first seven days of April, sailings were canceled. A total of 129 tankers were lost in American waters in the first five months of 1942.

“60 Vessels in 60 Days”

The Allied situation began to improve gradually. As the great wheels of American industry turned, a “60 vessels in 60 days” escort building program was proclaimed to overcome the shortfall in antisubmarine craft; 201 minesweepers that could be drafted to escort work were completed, and a subchaser training school was established in Miami. On April 1, Admiral Andrews set up a “bucket brigade” system whereby lightly escorted convoys proceeded only by day, stopping for the night in protected anchorages. Meanwhile, antisubmarine aircraft, such as long-range Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers and PBY Catalina seaplanes, were pressed into service.

Finally, on April 18, Andrews and Lt. Gen. Hugh A. Drum, feisty chief of the Army Eastern Defense Command, ordered a shoreline blackout and a dim-out of coastal cities. The U-boats were deprived of their sitting ducks, and ship losses along the Eastern Seaboard dropped to 23 that month. In July, there would be only three sinkings, and then none for the rest of the year.

The Americans were now able to start hitting back at Dönitz’s predators. After a determined chase south of Norfolk, Virginia, the old destroyer USS Roper sank U-85 with gunfire on April 14, 1942. It was the first U-boat kill of World War II by a U.S. Navy surface craft. On May 9, the Coast Guard cutter Icarus damaged U-352 with depth charges in shoal water off Cape Lookout, North Carolina. The submarine, on her maiden voyage, was then scuttled by her captain. Two more U-boats were sunk in June by the cutter Thetis and a Martin Mariner flying boat.

May brought another dramatic turnaround in Allied fortunes. With new construction and the release of destroyers and other escorts from the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, Admiral Andrews was able to organize the first strong offshore convoys, shepherded by more than 300 patrol planes based at 19 airfields. Dönitz started shifting his wolfpacks southward, and only six merchantmen were sunk along the East Coast that month.

Turning Away From the U.S. Coast

The gray wolves now found profitable hunting in the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, torpedoing 41 independent vessels totaling 220,000 tons in May. Almost half of these were tankers sunk off the Passes of the Mississippi. “U-boats showed the utmost insolence in the Caribbean, their happiest hunting ground,” said Navy historian Samuel Eliot Morison later. The southern onslaught was checked, however, when a complex of interlocking systems was set up to enable ships to transfer at sea from one convoy to another.

Dönitz’s gray wolves then retaliated by attacking independent ships off Panama, Trinidad, Salvador, and Rio de Janeiro. The U-boat operations were lengthened by the arrival of Dönitz’s 1,700-ton “milch cow” submarine tenders. The sinking of five Brazilian freighters off Salvador in August provoked Brazil into declaring war against the Axis. Escorts were drawn from the U.S. South Atlantic Fleet, and the convoy system was extended to Rio.

In the next three months, 1,400 vessels were escorted through Admiral Andrews’s highly successful interlocking system, and only three were sunk. Realizing, meanwhile, that happy time in the Western Hemisphere was over, Dönitz had started shifting his U-boats back to the North Atlantic for a renewed blitz on Allied convoys.

Operation Drumbeat was a coup for Dönitz’s gray wolves and an appalling episode for the Allies. During the first half of 1942, in coastal waters from Canada to the Caribbean, more than 360 merchant ships and tankers totaling about 2,250,000 gross tons went to the bottom. An estimated 5,000 lives, mostly merchant seamen, were lost.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments