By Mark Simmons

May 16, 1943, had been a sweltering spring day in England. At 9:39 pm, as the sun was dipping below the western horizon, leaving a rim of light and still good visibility, the first three of 19 Avro Lancaster bombers of No. 617 Squadron began to take off from RAF Scampton in Lincolnshire.

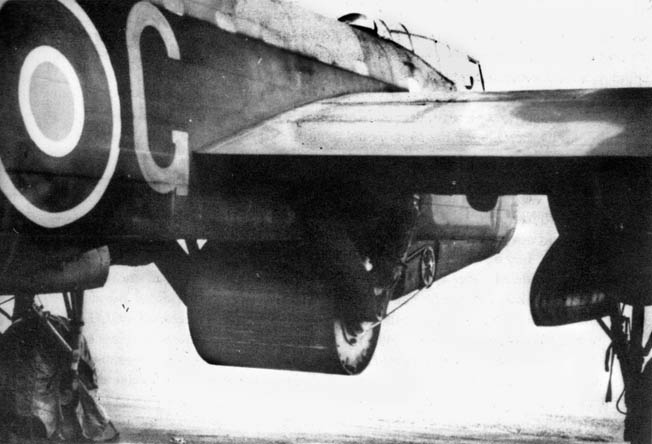

The bombers, under the command of 24-year-old Wing Commander Guy Penrose Gibson, took off three abreast, with a strange, round-looking object slung below each fuselage; Gibson called his aircraft a “pregnant duck.” The perimeter hedge of the airfield came up all too quickly, and the lumbering aircraft barely cleared it.

The takeoff was the result of years of planning after the Ruhr dams had been identified as the mainstay of German war industry. The Ruhr armament factories––located in Essen, Düsseldorf, Gelsenkirchen, Dortmund, Duisburg, and other industrial sites in the area––could be effectively eliminated, so went the theory, by destroying 45 power plants in a deluge released by breaching the dams. The targets were Germany’s “Achilles heel”; a successful attack would result in chaos and disruption in the industrial Ruhr. The Air Ministry felt the scheme should be “treated as urgent and of pressing importance.”

However, a review committee believed the same result could be achieved by attacking only two targets––the Möhne and Sorpe Dams, although they were different types of dam.

Sorpe was an earthen dam, its central core supported by earth ramps. Möhne was a gravity dam held in place by its own weight. Farther east, another dam––the Eder––provided water for the inland waterways and canals of the Weser Valley.

In theory, destroying the dams was all very fine, but how could it be achieved? Various types of ordnance were considered, including torpedoes, skimming bombs, bombs fitted with delayed-action fuses, and all types of depth charges. A depressing conclusion was reached that the amount of explosive required would exceed any existing aircraft’s payload.

Wing Commander C.R. Finch Noyes, a veteran of World War I, examined all the data on the dam scheme. In September 1940 his report argued that if 20,000 pounds of explosive were exploded against the face of a gravity dam like Möhne, 40 feet down, a breach was more than likely and “the dam would go.”

The method of attack would involve an aircraft flying low over the surface of the water and releasing a missile. It would sink and be detonated by a hydrostatic fuse activated by water pressure. During the winter of 1940 Finch Noyes refined his plan. An attack on the Möhne Dam would require 16 Vickers Wellington bombers carrying 64,000 pounds of bombs. There was still no decision on a type of skimming bomb or a torpedo of any sort.

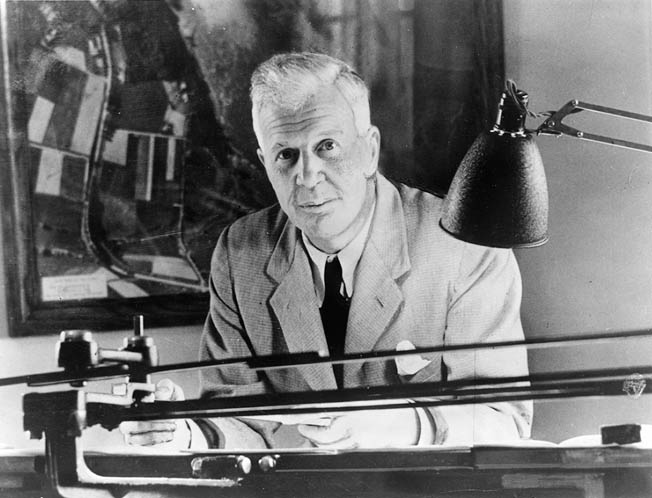

However, the Finch Noyes proposal was rejected by senior staff officers on the grounds the delivery system would not work. But the dams remained priority targets. Finch Noyes believed that a low-level attack with a new weapon that would strike the dam wall was required. Over a year later the brilliant engineer Barnes Wallis designed just such a weapon.

The Bounding Bomb

In the spring of 1943, the 54-year-old designer Wallis was then working for Vickers-Armstrong, being an old hand in the aeronautical industry. He had originally trained as a marine engineer, and in his early career he was involved in the design of airships. Later he concentrated on bomber aircraft such as the Wellesley and Wellington.

He had already been thinking about the dams and believed a 10-ton bomb would be required, but no available aircraft could carry such a bomb. So he set about designing a six-engine bomber. However, using 1:50 scale models of the Möhne Dam proved that even a 10-ton bomb dropped from 40,000 feet close to the dam might not breach it.

Wallis did not give up, and luckily A.R. “Dick” Collins, another scientist who had been exploring the Finch Noyes line of thought, had managed to detonate a scaled-down charge against a model dam with good results. Collins and his assistants at the government’s Road Research Laboratory became known as the “Dam Blasters.”

After the war Wallis wrote to Collins that what became “the bouncing bomb was originated solely to meet the requirements so convincingly demonstrated by your experiments that actual contact with the masonry of the dam was essential.”

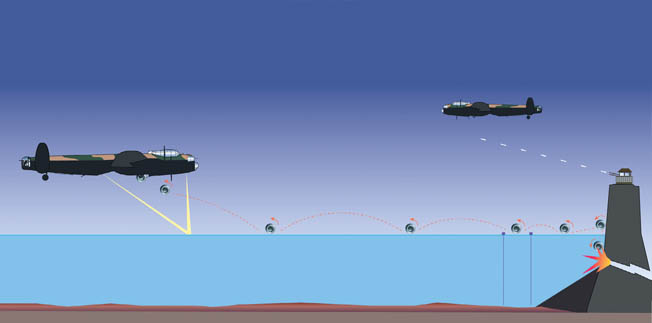

In the spring of 1942, Wallis came up with his answer: a bouncing bomb. He later recalled, “I had the idea of a missile which, if dropped on the water at a considerable distance upstream of the dam, would reach the dam in a series of ricochets, and after impact against the dam would sink in close contact with the upstream face of the masonry.”

The idea went through several experiments. Those at the National Physical Laboratory at Teddington, in two large indoor tanks, were witnessed by Sir Henry Tizard, scientific advisor to the Air Ministry, who recommended a “full-scale test is desirable with a Wellington.”

Over a period of six months, several tests took place at Chesil Beach near Weymouth in Dorset. By January 1943 Wallis’s modified cylinders were beginning to bounce without shattering on impact with the water. During the fourth trial, the bomb bounced more than 20 times, and in the next trial traveled 1,315 yards.

This proved that the concept would work; the German dams could be attacked successfully with a bouncing bomb. Now he needed to convince those in charge.

Approving the “Air Attack on Dams”

Wallis sent his findings to the Air Ministry in a document entitled “Air Attack on Dams.” He was confident that a 6,500-pound charge exploded in contact with the masonry wall of a dam 30 feet below the surface of the water could breach “the largest gravity dams in Germany.” And such a bomb could be carried by a Lancaster bomber.

The differently constructed Sorpe Dam would be “self-destroying if a substantial leak could be caused within the central concrete wall.” This could be achieved if detonation occurred on the water side of the dam at a suitable depth. In many quarters the proposal received a sympathetic hearing.

However, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris, C-in-C Bomber Command, was not in favor, bemoaning the loss of one of his squadrons for two or three weeks. He wrote, “This is tripe of the wildest description. There are many ifs & ands that there is not the smallest chance of it working.” And, “The war would be over before it works.”

Harris did have a point. Even after seeing films of airborne tests, he remained skeptical. He had enough operational problems due to a high loss rate of his aircraft. For April 1943, production of Lancasters was estimated at only 123; Wallis wanted a quarter of these for a doubtful operation.

Wallis was soon told by his employers at Vickers-Armstrong that he was upsetting members of the air staff with his “silly nonsense about the destruction of the dams” and to drop it.

Events elsewhere, however, were moving in favor of the project. Air Chief Marshal Sir Charles Portal had already been proposing sending a special squadron of Handley Page Hampden bombers armed with torpedoes against the Möhne Dam. When Harris appealed to him, he refused to dismiss the plan, and further, he backed it by allocating three Lancasters for trials.

Wallis, in a favorable reversal of fortune, was told by Portal that the operation was to go ahead and that he wanted an attack in the spring, when the Möhne reservoir would be full. This was still a tall order for Wallis; up to the time of this meeting, February 26, no full-size bomb had been tested and was not even on the drawing board.

Squadron X

Once the decision to back Wallis had been taken, it became an RAF priority. Harris, the irascible C-in-C of Bomber Command, on March 15 gave the task to No. 5 Bomber Group, commanded by Air Vice Marshal R.A. Cochrane and told him to form a new squadron. It should be made up where possible of experienced volunteers who had completed at least one tour of 30 operations. Harris nominated Wing Commander Guy Penrose Gibson, who had served under him when commanding 5 Group, to command the squadron on the dangerous mission.

Gibson at that time was about to stand down as commander of 106 Bomber Squadron at Syerston, having flown 42 sorties in Hampdens, 99 with Bristol Beaufighters, and a further 29 with Avro Manchester twin-engine bombers and its four-engine successor, the Lancaster. He was short, stocky, and energetic; some considered him cocky or arrogant. He was no doubt looking forward to some leave time when he was posted to 5 Group headquarters, where Cochrane asked him to fly one more mission.

Gibson agreed, and was told he would command a new, specially formed squadron based at RAF Scampton, and the operation would not be carried out for two months, when his crews would have to be proficient in low-level flying at night.

The new squadron was created on March 17 and code-named “X.” Postwar, the impression was fostered, partly by the 1955 commercial film of the raid (The Dam Busters), that Gibson personally chose all the aircrew members of the squadron; undoubtedly he did choose some but not all. Of the 133 who would take part in the attack, 89 were British, 28 Canadian, 13 Australian, two from New Zealand, and one American.

Three complete crews came from 97 Squadron, one piloted by Flight Lieutenant Joseph C. McCarthy, Royal Canadian Air Force, who was the lone American wearing dual shoulder flashes: “USA” and “Canada.” He had been born in St. James, Long Island, but grew up in Brooklyn. He joined the Royal Canadian Air Force in 1939 anxious to get into the war, arriving in Britain in 1942 to serve with Bomber Command. McCarthy was one of those approached personally by Gibson, and his crew agreed to go with him.

Pilot Officer L.G. Knight, Royal Australian Air Force, came from 50 Squadron with his crew. Sergeant R. Kellow, his Australian wireless operator, explained: “The offer presented to us sounded interesting and with our faith in each member’s ability, we made up our minds there and then that we would accept the offer and move across as a crew to this new squadron.”

On March 24, Squadron X became operational, and three days later it became No. 617 Squadron.

Making the Upkeep Bomb

A month earlier, Wallis had begun work on “Upkeep,” as the bouncing bomb was code-named. The full-size version would be seven feet, six inches in diameter; the central cylindrical core would hold the explosive charge inside an external steel casing braced by wooden struts. The result looked like a beer barrel.

Each Upkeep bomb weighed 2,250 pounds and was filled with 6,600 pounds of Torpex, an underwater explosive used in torpedoes. When the Upkeeps were dropped, they would be given a backspin at 500 rpm. The bomb-aimer, ideally, would need to release it at 425-475 yards from the target.

Three hydrostatic pistols of a standard type used by the Royal Navy would provide the fuse. By March 2, manufacturing began at Vickers-Armstrong, which would provide the cylinders while the Royal Ordnance factories would insert the explosive.

Lancaster B.IIIs were modified to carry the bomb. They were powered by four Merlin 28 engines built under licence by the Packard Motor Company of Detroit. Twenty-three Lancasters would be modified; 20 would join the squadron while three would be used in trials. The B.IIIs had their bomb-bay doors and front defensive turrets removed.

Practice trials now moved to the Thames estuary off the North Kent coast at Reculver, which was easier to cordon off from observation than was Chesil Beach. On April 13 new trials took place but were disappointing as the bombs disintegrated on impact. Wallis waded out to examine the fragments and reasoned they had been dropped from too high an altitude.

On the final run that day, a bomb was dropped at 50 feet. This time the steel cylinder bounced but damaged the elevator of the Lancaster. The test pilot had difficulty landing the aircraft.

The tests continued. Wallis explained to Gibson that the height of release had to be decreased or the attack would likely fail. It had been set at 150 feet but needed to be reduced to 60 feet. Wallis knew that, in the face of flak, this would increase the dangers, but Gibson agreed it was necessary. More trials followed, and Wallis determined that Upkeep needed to be dropped at 60 feet at 210-220 mph.

By May 13, the Upkeep bombs would be “sufficiently robust” to withstand repeated impact with the water and soft targets and had “satisfactory balance” in their cylindrical garden-roller form. This was the first time that the crews of 617 Squadron laid eyes on Upkeep, their weapon.

Training For the Raid

While testing was taking place, Gibson had already begun training his crews. He had decided on two flight commanders: Squadron Leader H.M. Young, DFC, and Squadron Leader H.E. Maudslay. Young proved an able deputy for Gibson, who was often called away to the Reculver trials. Maudslay from 50 Squadron was admired by the aircrew and held in “the greatest respect.”

It was not until March 29 that Cochrane revealed the targets to Gibson, who was relieved it was not the battleship Tirpitz, which had been the rumor, then known to be anchored in a Norwegian fjord.

During April, Gibson reported “daily intensive flying training carried out when weather permitted.” Sergeant F.E. Sutherland, RCAF, described the training: “I guess we had a lot of cross-country flying up as far as Scotland and round the Lake District, just low-level. I remember those canals in northern England or Scotland and flying along them, and I think it was all navigation and map reading.”

At the end of April, Gibson reported all crews were competent to navigate at night and pinpoint locations at low level. Also practice with standard 11.5-pound bombs had been conducted on the Wash at the Wainfleet range. From April 26, crews had been instructed to bomb from 60 feet and at 210 mph.

Training switched to the Eyebrook Reservoir, near Uppingham in Rutland. The reservoir had a straight dam wall and was near full. Four wood and canvas towers were erected to simulate the towers on the Möhne Dam. Exercises began at 4:00 pm on May 4, startling nearby residents who took to their cellars and air-raid shelters.

However, they soon got used to the flights and began to watch the aircraft coming in low over the surface of the reservoir, releasing purple flares as they pulled up over the dam. Near Colchester, the Abberton Reservoir served to simulate the Eder Dam. Being more remote, there were no onlookers there.

Special aids were needed for the bomb-aimer to release Upkeep at the right point of the reservoir. A simple triangular wooden sight with two vertical nails was devised, through which the aimer looked. When the dam lined up with the two nails, the bomb was released.

Another problem was to keep the large aircraft stable at the low height long enough for the bomb-aimer. For the height requirement, spotlights were fitted beneath the wings, arranged in such a way that the beams merged on the water at 60 feet below the aircraft. To achieve this, the navigator stood behind the flight engineer on the pilot’s right looking out of the Perspex blister; he then had to instruct the pilot to fly higher or lower to settle at the correct height.

This method had been tried by aircraft attacking U-boats on the surface; however, it had proved of little use because of choppy seas in which the meeting beam could be lost. On the flat surface of the reservoir, though, it proved ideal.

During the night of May 14-15, 19 aircraft flew their last practice exercise before the real thing: Operation Chastise.

“Full dress rehearsal on Uppingham Lake and Colchester Reservoir. Completely successful,” Gibson wrote in his logbook. Barely 48 hours later the mission would be launched.

The Six Dams of Operation Chastise

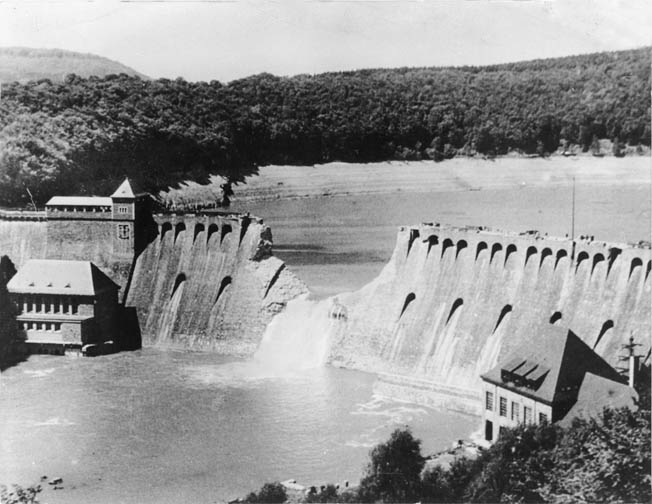

Six dams were outlined for attack in the Air Ministry order sent to 617 Squadron on May 15. The Möhne Dam, completed in 1913 and holding 134 million cubic meters of water, was 26 miles east of Dortmund on the junction of the Möhne and Heve Rivers. The nearby countryside was heavily wooded, which would help conceal the aircraft on approach. Below the dam was a large power station. The dam had two towers that would aid the bomb-aimers; both towers, however, held flak guns.

At the nearby village of Gunne were more flak guns that could engage the attacking aircraft. None of the AA guns were of heavy caliber, however, because the bigger guns had been withdrawn to defend the cities.

The Sorpe Dam was six miles southwest of the Möhne; it had a different structure and was about half the size. Bomber Harris argued this was the wrong dam to attack. “I knew, and asserted from the start,” he said, “that the Sorpe Dam was the wrong construction to collapse from the bouncing bomb, though there was a faint chance that it might start a leak crack in the concrete ‘blade’ and then the escaping water might do the rest.” But the decision was taken out of his hand.

The third Ruhr Dam outlined for attack was the Lister, much smaller than the other two but of a construction similar to the Möhne. Another dam, the Diemal, was of masonry construction.

The final Ruhr target was the Ennepe Dam. Like the Möhne, Diemal, and Lister, it curved in a convex manner into the reservoir. It was 20 miles due south of Dortmund, and the smallest of the targets.

Of the two dams in the Weser Valley, the Eder was the biggest and held 202 million cubic meters of water; its the reservoir was over seven miles in length. There were no flak defenses, for it was difficult to approach.

Operation Chastise was scheduled for Sunday, May 16. The 19 aircraft of 617 Squadron received final maintenance checks. The process to attach Upkeeps to cradles bolted below the Lancasters took about half an hour per aircraft.

Other than the Sorpe Dam, all the targets were to be attacked at right angles to the dam wall at a speed of 220 mph and at 60 feet altitude. At almost the last minute, Wallis decided that the Sorpe should be attacked in a different manner. Here the aircraft would fly along the top of the dam wall keeping the port outer engine on the crest and drop Upkeep in the middle. In theory, the bomb would then roll down the sloping support wall and explode 30 feet below the surface. It was hoped then the shock waves would crack the central core and water leakage would cause the collapse.

The weather forecast for May 16 was good. At 4:45 pm, a message from 5 Group arrived at Scampton: “Execute Operation Chastise 16/5/43 Zero Hour 2248.”

Now all members of the air crew could be told the nature of the target at what Flight Sergeant T.D. Simpson, a rear gunner, called, “the largest briefing I ever attended.”

Gibson told them they were going to “attack the great dams of Germany” and if they did not succeed, “you’re going back tomorrow night.”

Wallis then described each target in detail, and Cochrane told them of the need for secrecy at all times, as Upkeep might later be used against other targets.

The 19 aircraft were to be divided into three waves. Gibson would lead the first nine planes, divided into three formations and taking off at 10-minute intervals. They would fly over the North Sea, making landfall at the Scheldt Estuary and, skirting German defenses, they would attack the Möhne Dam (Target X).

Gibson would coordinate the attacks. Once the Möhne had been destroyed, remaining aircraft would fly to the Eder Dam (Target Y). After that, any aircraft still loaded with Upkeeps would move to the Sorpe (Target Z).

The second wave of five Lancasters led by Wing Commander McCarthy would attack the Sorpe flying over the Dutch coast and the German border farther north of the first wave.

The remaining five aircraft would form a mobile reserve, ready to attack wherever needed. They would take off 21/2 hours after the others and be directed to the targets by a radio link from 5 Group.

Before takeoff, all crews were allowed to study the models of the Möhne and Sorpe Dams but, unfortunately, the model of the Eder was not ready. Sergeant F.E. Sutherland admitted he was frightened. “It was really scary to see the dams. The Möhne Dam had the flak towers and it just looked really rough. After a while you get a feeling like you were going to Essen, which with its 50,000 flak guns you know it’s tough. But this one seemed to be worse; it just seemed to be the ultimate in dangerous things to do, so I was scared, really scared.”

After the briefing the crews had their evening meals. Soon the time came for the men to be ferried out to the aircraft. Many saw Upkeep for the first time and G.L. Johnson, McCarthy’s bomb-aimer, called it a “dustbin.” Crews of the first two waves went through preflight tests. Engines were run and then shut down again.

At 9:28 pm, the signal was given, and aircraft AJ-E of Flight Lieutenant R.N.G Barlow, RAAF, began to roll. The aircrews of the third wave watched their comrades take off; they would have to wait two nervous hours for their own takeoff. Operation Chastise had begun.

The Three Formations Take Off

Over the North Sea, each Lancaster tested its surface spotlights. Strong winds delayed the first formation, and the first wave reached the enemy coast at the wrong place. Instead of making landfall on the Scheldt Estuary, they flew over heavily defended Walcheren Island.

The Lancasters were proving difficult to navigate at such low altitude and needed constant correction. Gibson took his aircraft up to 300 feet to make it easier for his navigator, Pilot Officer H.T. Taerum, to plot a new bearing. The bomb-aimer, Pilot Officer F.M. Spatland, used a roller map to follow the terrain and was able to help Taerum when they descended to the required 100-foot altitude. They soon picked up the Wilhelmina Canal near the River Rees. Here they came under fire from flak barges on the river. Luckily, none of the aircraft was damaged.

Also, they were crossing more unplanned points of resistance. Near Dorsten all three Lancasters were caught in searchlights and fired upon. AJ-M, Flight Lieutenant Hopgood’s plane, received light flak damage to the port wing but flew on.

The last turning point was the junction of several railway lines near Ahlen. Finally, AJ-G, Gibson’s aircraft, breasted some tree-covered hills and there below them was the moonlit Möhne Reservoir. To Gibson’s surprise, the other aircraft of the first formation that had lost contact with each other turned up at the reservoir at about the same time.

The second formation left Scampton at 9:47 pm, led by Squadron Leader H.M. Young in AJ-A, following Gibson’s lead. Navigation in this case was better, and the formation made landfall over the Scheldt Estuary. Like Gibson, they had to take evasive action to avoid flak. Young’s formation reached the Möhne at 12:26 am, arriving individually. Flight Lieutenant D.J. Shannon in AJ-L arrived at the Möhne and was engaged by flak gunners firing from one of the dam’s towers.

The third formation took off from Scampton at 9:59 pm. They ran into more trouble than the others, reaching the Scheldt behind schedule. At the turning point at the junction of the Rees and Dulmer Rivers, Flight Lieutenant W. Astell’s Lancaster AJ-B was caught in a flak crossfire. It flew on for a short distance with pieces falling off, then burst into flames and exploded when it hit the ground.

Striking the Möhne Dam

About 12:20 am, Gibson informed the other aircraft already at the Möhne: “Stand by, chaps. I’m going to look the place over.” He took AJ-G on a circuit of the area. Reporting that he “liked the look of it,” he then warned the others to be ready to attack. Hopgood in AJ-M was told to be ready to take over the mission if Gibson were shot down.

AJ-G made its final approach at 230 mph. All aboard concentrated on their tasks; Flight Sergeant G.A. Deering in the front turret engaged the dam’s defenses.

Flight Lieutenant D.J. Shannon and his crew in AJ-L watched AJ-G going in, flak fire intensifing as they got closer to the dam, but they crossed through it safely and released their Upkeep at 12:28. The moon was bright with good visibility.

Gibson’s rear gunner saw the bomb bounce three times and, after about 10 seconds, recalled there was “a terrific explosion” and a surge of water. However, once the water settled, the dam was still standing.

Gibson then called in Hopgood’s AJ-M to attack, just as the two remaining aircraft of the third formation arrived. The German gunners were fully alert now. AJ-M was hit on the outer port engine and the starboard wing. The Upkeep was dropped late and bounced over the dam wall, landing on the power station below. AJ-M crossing the dam was already in flames. Hopgood climbed to about 500 feet, then one wing fell off and the plane blew up. Gibson reported he thought some of the crew might have bailed out due to Hopgood’s heroic attempt to gain height. Indeed, three did, and two survived to be taken prisoner.

Operation Chastise was off to a bad start. Gibson and Flight Lieutenant H.B. Martin, flying AJ-P, ensured the effort did not falter, though. Gibson came in slightly ahead and to starboard of Martin to distract and engage the flak gunners. AJ-P was hit but in none of its vital parts. At 12:38 am, Martin’s bomb-aimer dropped the third Upkeep. Again, it hit the dam wall although not in the center, having veered off course, and exploded on the left bank of the reservoir. The dam remained intact.

Gibson next called Young forward in AJ-A, while he patrolled the far side of the dam to again distract and engage the flak gunners. Gibson noticed Young’s Upkeep made “three good bounces” and exploded dead center on contact with the dam that still apparently held.

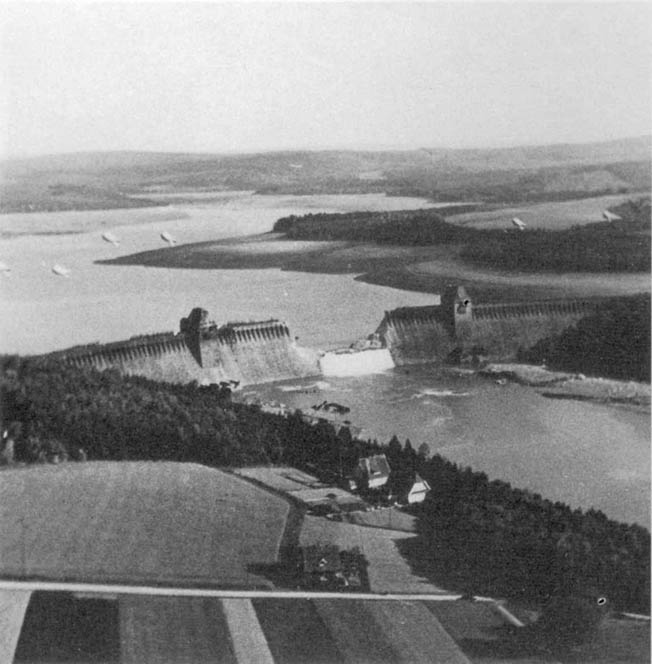

But Young’s bomb had breached the dam although it was not immediately apparent from the observing aircraft. Gibson ordered forward his fifth aircraft, AJ-J, piloted by Flight Lieutenant D.J.H. Maltby. On his approach, Maltby suddenly realised the top of the dam wall was crumbling and recalled, “There was a breach in the centre of the dam.”

Maltby dropped his bomb, which bounced four times, struck the dam, and exploded. He reported, “Our load sent up water and mud to a height of a thousand feet.”

Gibson went in closer and saw the dam shattered and water surging down the valley. At 12:56 am, he transmitted the signal for success. However, they could not linger and admire their handiwork. The aircraft that had expended their bombs turned for home while Gibson, accompanied by Young, now deputy leader, and the three remaining aircraft with bombs, headed for the Eder, 14 minutes flying time away. They made their way individually to the target.

Back at the 5 Group operations room, despair at the loss of two aircraft soon turned to joy when the success signal came through and was confirmed. Bomber Harris congratulated Wallis on the success of the mission, saying that now he could even “sell me a pink elephant.”

Eder Dam Breached

The five remaining Lancasters had trouble finding the Eder because the area was covered in mist. Gibson found it first but was too far to the west and spent several minutes flying west above the narrow part of the reservoir lying beneath the surrounding steep, tree-covered hills. The area around the dam itself was luckily clear of mist. Young joined him fairly quickly, but neither had an Upkeep.

The other armed aircraft arrived shortly. There were no flak defences at the Eder Dam. About 1:30 am, Gibson ordered Shannon in AJ-L to attack, but the approach was difficult. Three times he tried it without releasing his Upkeep, unable to reach the right height. Maudslay in AJ-Z then tried twice with the same result. Shannon came in again and dropped his bomb. This time it bounced twice before striking the dam with a now familiar explosion and water spout. Shannon used his landing lights to aid his steep climb after crossing the dam over the surrounding hills.

On Maudslay’s third run, his bomb-aimer got Upkeep away but late, and it exploded on contact with the parapet. Most observers believed AJ-Z was not damaged by the detonation of her own bomb as the aircraft was well clear of the dam and was seen banking away steeply. But then it vanished without a trace.

Finally, Pilot Officer L.G. Knight’s AJ-N, the last bomb-carrying aircraft, attacked. Like the others, Knight had difficulty lining the aircraft up after the steep descent to the reservoir and made one dummy run. However, on the next run his Upkeep was released, bounced three times, and hit the dam to the right of center. Gibson saw the dam collapse “as if a gigantic hand had pushed a hole through cardboard.” After Knight’s run, Shannon’s bomb-aimer heard “one hell of a bang,” then Buckley, the rear gunner, yelled over the intercom, “It’s gone.”

At 1:54 am, Gibson signalled “Dinghy,”the code word indicating that the Eder Dam had been breached.

Maltby’s AJ-J was the first back to Scampton. With an uneventful trip back, he landed at 3:11. Maltby met the adjutant, Flight Lieutenant H.R. Humphries, at the debriefing room. Maltby was asked, “Hello, Dave, and how did it go?”

Maltby’s reply: “Marvelous, absolutely marvelous. Water, water everywhere, wonderful, wonderful.”

Knight’s AJ-N was the last back, landing at 4:20 am. It was time to count the cost. Four aircraft were missing. Other crews had witnessed the losses of Astell’s AJ-B and Hopgood’s AJ-M. Maudslay’s AJ-Z had not crashed at the Eder; it was brought down by flak near the Rhine oil refinery at Emmerich. There were no survivors.

Young’s AJ-A had been shot down crossing the Dutch coast near Castricum-ann-Zee at 2:58 am. None of the crew survived. Bodies were later washed up on the coastline, confirming the loss. They were not the only aircraft of 617 Squadron downed that night.

“Very Hot Reception From the Natives” at Sorpe Dam

The aircraft of the second wave to attack the Sorpe Dam left Scampton before the nine Lancasters of the first wave but had farther to go on the longer northern route. They were led off by Flight Lieutenant R.N.G Barlow in AJ-E at 9:28 pm. Barlow crashed near Haldern at 11:50 pm. It is believed from German reports to have hit high-tension wires, possibly after receiving flak damage. Their Upkeep’s self-destruction device was not armed, so it did not explode and was recovered intact by the enemy.

Flight Lieutenant J.L. Munro’s AJ-W took off from Scampton right after Barlow. The northerly route joined Gibson’s first-wave route at the Rees turning point. AJ-W was damaged crossing Vlieland by fire from a flak ship. Sergeant W. Howorth, the front gunner, felt the aircraft was badly damaged: “The intercom was put out of action and VHF for communication with other aircraft of the wave was lost.”

Power for the rear turret was also lost. “We could not speak to the other planes in the wave,” Howorth reported, “and were left with one rather unreliable compass and had very little defence against fighters.” They had little choice but to try and return home.

AJ-K’s Pilot Officer V.W. Byers, a Canadian, had taken off at 9:30 pm. As with Barlow, nothing more was heard from this aircraft. It is likely it was shot down while flying low over the heavily defended Dutch island of Texel. AJ-H Pilot Officer G. Rice’s crew reported an aircraft being caught by flak “off Texel” while flying at 300 feet.

Rice’s AJ-H itself suffered a bizarre fate. Crossing the narrow neck of land at Vlieland, Rice was too low, and he had to pull up sharply. He climbed to 300 feet to check position. Returning to low-level flying over water, the flight engineer realized too late that the altimeter was giving a wrong reading. A heavy shudder struck the aircraft. Rice pulled up and felt another “violent jolt.” They had lost their Upkeep. The operation was over for AJ-H.

American Flight Lieutenant Joe McCarthy was in trouble before he left the ground. His AJ-Q had developed a coolant leak in the starboard outer engine, so he and his other six crew members had to change over to the only reserve aircraft, AJ-T, which was “bombed up” but had no VHF radio or Aldis lamps.

Like all the others, the crew of AJ-T found navigation difficult. However, 15 minutes after midnight they reached the Sorpe. McCarthy’s aircraft was the only one of his five-plane section to reach the target by flying low, as he recalled: “Very hot reception from the natives. When we crossed the coastline at Vlieland, they knew the track we were coming in on, so their guns were pretty well trained when they heard my motors. But, thank God, there were two large sand dunes right on the coast which I sank in between.”

McCarthy was puzzled to be alone but did not hesitate in making his attack. It took them 10 runs before Sergeant Johnson, the bomb-aimer, was satisfied enough to release the bomb close to the center of the dam. McCarthy turned away to port, climbing rapidly with the loss of weight. There was evidence of damage to the top of the dam wall, so the aircraft lingered a while, hoping it would collapse, then turned for home at 1:00 am.

Despite their best efforts, they had not breached the dam. In fact, four of the target dams remained intact, while only five Lancasters of the Mobile Reserve remained. It was now their turn.

The Mobile Reserve Attacks

Once 5 Group learned the Möhne and Eder Dams had been breached, it ordered the third wave to attack the Lister Dam. The third wave took off singly and followed Gibson’s southern route over the Scheldt Estuary. AJ-C was the first aircraft to take off at 9:09 am on Monday, May 17, captained by Pilot Officer W.H.T Ottley.

Ottley was followed by Flight Sergeant W.C. Townsend’s AJ-O. While crossing the enemy coast, Townsend’s navigator noticed a flash to starboard. “Ahead and to starboard” he noted, “searchlights broke out and an aircraft was coned at something over 100 feet, more searchlights and lots of flak and a terrific explosion in the sky.” It was Ottley’s AJ-C.

Flight Sergeant K.W. Brown of AJ-F saw it, too, and that “his tanks exploded then his bomb.” Miraculously, one of Ottley’s crew, rear gunner Sergeant F. Tess, survived. He was blown clear of the Lancaster with third-degree burns and spent the rest of the war as a POW.

AJ-S, with Pilot Officer L.J. Burpee, left Scampton two minutes after Ottley and was soon posted missing. His end was also seen by Mobile Reserve crews. Brown in AJ-F crossed the enemy-held coast at 1:30 am, finding his compass in error by five degrees. Shortly thereafter, the crew witnessed AJ-S being shot down. Brown’s bomb-aimer, Sergeant Oancia, saw AJ-S stray off course over the Luftwaffe base of Gilze-Rijen. It was hit by ground fire and went down in flames, the bomb exploding as it hit the ground.

Brown ran into trouble trying to shoot up a train that “did them no favours,” according to Sergeant H.B. Feneran, the flight engineer, but merely drew attention to them. Over Germany and fearing fighters, Brown flew so low he once followed a road below the surrounding tree line. Crossing the Möhne, they saw a clear break in the dam and water pouring down the valley.

Brown’s AJ-F was the second Lancaster to attack the Sorpe Dam. Mist had come down thickly, and it took them quite a time to find the target. At about 3:14 am, the mist cleared, and their Upkeep was released. It rolled down the sloping bank and exploded in the moonlight with a great plume of water, but the dam remained intact. At 5:33, with the sky becoming light, AJ-F returned to Scampton.

The fourth reserve aircraft, W.C. Townsend’s AJ-O, almost stalled on takeoff and went through the top of the perimeter hedge before gaining height. According to his navigator, Pilot Officer G.L. Howard, Townsend flew his Lancaster “as if it were a Tiger Moth trainer.”

At 2:22 am, Townsend attacked the Ennepe Dam. Again, the crew had trouble finding the target. Finally, they found it through drifting mist, but it took four runs before the bomb-aimer was able to release Upkeep. The crew saw the bomb explode but also saw it had fallen short, about 50 meters from the wall.

Night fighters had been scrambled to intercept this aircraft, but AJ-O, flying low and on a roundabout route, got back to Scampton, landing safely in daylight at 6:15 am. An oil-pressure concern had forced them to shut down one engine, requiring Townsend to land on three.

The final aircraft of the reserve, AJ-Y, under Flight Sergeant C.T. Anderson, had difficulty finding the target in the mist, which was not helped by 5 Group, which had ordered him first to attack the Diemal Dam and then changed it to the Sorpe.The rear turret of AJ-Y was out of action due to a breakdown, and was dawn coming fast. Anderson decided to turn back. He landed at Scampton at 5:30, only the second Lancaster to return with its Upkeep.

The efforts of the Mobile Reserve brought Operation Chastise to a close in the early hours of May 17.

The High Cost and High Reward of Operation Chastise

For the members of 617 Squadron and the ground staff at Scampton, the promising results of Operation Chastise were tinged with the feeling of heavy loss: eight aircraft had not returned and 56 men were lost. That Monday morning the sorrowful task of contacting bereaved relatives began.

However, despite this, there was a mood, a gathering strength of elation. Messages of congratulation began to come in. Cochrane to Gibson: “All ranks in 5 Group join me in congratulating you and all in 617 Squadron on a brilliantly conducted operation.”

Early that morning, reconnaissance Spitfires were over the dams and the surrounding areas, bringing back dramatic pictures of the destruction caused by the floods. The Möhne Dam had a gap 250 feet long and 72 feet deep ripped in its wall. Of the 130 million cubic meters of water it had contained, 116 million had escaped in 12 hours, floods extended over 65 kilometers, and countless bridges and buildings were destroyed. Two power stations also had been swept away.

The official German figures were that, between the Möhne and Ruhr Valleys, 11 factories were destroyed, 114 damaged, 25 road or rail bridges were wiped out, plus numerous power stations, pumping stations, and water and gas facilities were affected. There were some 1,300 casualties––over 1,000 dead, the rest missing.

The picture with the Eder was different as the RAF’s aim was to disrupt river and canal communications. The Eder Dam had a 230-foot wide and 72-foot deep gap blasted in its wall. Over 150 million cubic meters of water had poured out, and four nearby power stations were put out of action. Water spread for a considerable distance, breaking the banks of the shallow rivers, and a large area of valuable agricultural land was flooded.

Regarding the Sorpe, it was concluded that McCarthy’s lone attack had come close to success, but the wall had held. No damage was discovered at the Ennepe Dam.

Albert Speer, the German Minister of Armament and War Production, flew over the area on the morning of May 17. For two days he conducted inspections and concluded that the water supply to the Ruhr was “imperiled” and this might bring industry “to a standstill.” There is no doubt that the effect on industrial output for Germany was not long lasting. However, there were serious implications for agricultural output as much of the flooded land could not be tilled for years afterward.

Some 30,000 workers were diverted into the Ruhr area to complete repairs, away from other projects like completing the Atlantic Wall—a string of coastal fortifications designed to prevent a cross-Channel Allied landing. Also, antiaircraft batteries were moved from other areas to defend the dams. Hitler raged at Reich Air Marshal Hermann Göring for permitting the raid to happen, asking why the Luftwaffe allowed such a handful of aircraft through.

German war effort.

Elation in the Allied press was understandably widespread. The London Daily Mail headline on May 18 crowed: “The Smash-Up: RAF Picture Testifies to Perfect Bombing.” The Illustrated London News said the raid was “A Titanic Blow at Germany.” And the New York Times noted: “The RAF has secured another triumph and with unexampled daring, skill and ingenuity it has blasted two of Germany’s important water dams” and “all Americans should congratulate Wing Commander G.P. Gibson on his feat and mourn with him the loss of eight aircraft and their gallant crews.”

On May 28, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth visited 617 Squadron at Scampton. Gibson was awarded the Victoria Cross, five other members of the squadron received the Distinguished Service Order (DSO), 14 the Distinguished Flying Cross, two Gallantry Medals, and 12 Distinguished Flying Medals; the American Joe McCarthy received the DSO.

The bombing of the dams did not, in itself, win the war. But the raid did strike a blow at the Third Reich’s industrial heartland and seriously diminished its capacity to continue churning out the tools of war that Hitler so desperately needed.

Yet in the last 2 months of the war German war production of ALL military equipment–tanks, planes, etc reached its all time high. With one exception–oil and therefore gas. They had it but couldn’t move it.