By Robert Barr Smith

Through the long, lovely days of the summer of 1940, almost two years before Operation Biting or the “Bruneval Raid,” Royal Air Force Spitfire and Hurricane fighter planes turned back the might of the Luftwaffe over southern and southeastern Britain. The Battle of Britain was won by the professionalism and courage of a handful of young pilots, by just enough of two fine fighter aircraft, and by a sophisticated system of fighter direction.

At the heart of British ability to concentrate outnumbered fighter assets against the mass of German attackers lay radar, then a relatively unheralded device. Britain had the lead in radar development, but it was no secret that the Germans were working on it as well.

England and Germany Locked in Technology Race

The radar war had begun well before German troops invaded Poland in the fall of 1939. The Germans were intent on discovering whether Britain was developing radar, and if so, what its characteristics were. Accordingly, as early as July 1939, a German zeppelin was dispatched to hover off the English coast and listen in secret for electronic emanations that might give some clue. In this and subsequent flights, the Germans learned nothing, for they were looking for radar pulses on a wavelength entirely different from what the British were using.

For their part, the British were aware of German Seetakt,a maritime gunnery radar, and of a flak radar the Germans called Freya,after the Norse goddess of love and of the dead. Before the device was ever identified, the British had heard about Freya. Dr. R.V. Jones, the wizard of British radar, knew that in German mythology the goddess Freya had a magic necklace, guarded for her by the servant Heimdal, who could see for a hundred miles. Could the Germans, wondered Jones, have been so dense as to name a radar Freya for this reason? The answer was yes.

Measures and Countermeasures

The British developed the means to jam Freya, which in time had extended its range to about 75 miles. They could even feed it false data and translate the messages it was sending to night fighters and flak guns. By the end of 1941, however, it became apparent that the Germans had developed something more effective than the Freyageraet, for German flak and night-fighter defense had markedly improved. Royal Air Force losses increased to about 4 percent per raid, an unacceptable level. Wellington bombers on reconnaissance missions had picked up many emanations from some new device, and now British intelligence went to work to find out what the Germans were up to.

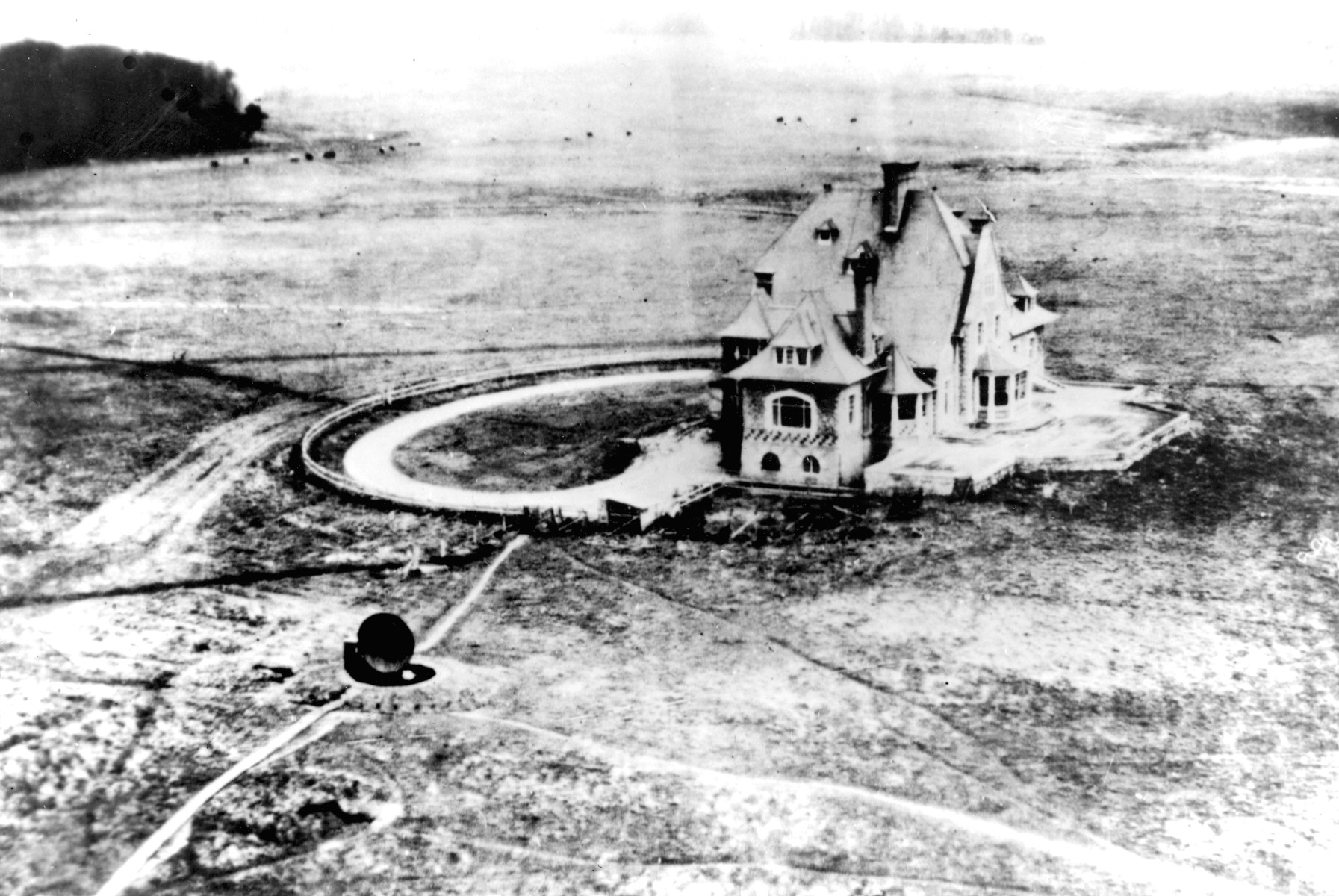

Reports from the French resistance, plus photographs by the PRU, the RAF Photo Reconnaissance Unit, suggested that a new radar apparatus had come into service. It was short range, only 20 miles, and it had a very narrow beam, but was very accurate indeed. And it could give the altitude of a target as well as its bearing, which Freya could not. It was made by Telefunken, and it was called Würzberg. When one of these new devices appeared on a cliff some 12 miles north-northeast of Le Havre, the PRU set out to get a really good picture of it.

Aerial Reconnaissance Reveals New German Radar System

And so, in early December, Flight Lt. Tony Hill pushed his souped-up, unarmed Spitfire across the English Channel and took a superb set of aerial photographs. The results were clear. There it was, a thing that looked like a large dish, pointed across the Channel toward England. Just behind it stood a large, Victorian gingerbread villa, surrounded by fields.

The next step, of course, was to devise a countermeasure for this new radar, but to do that the British scientists needed to know more about the device. The best way to find out how it operated would be to examine it closely. Lord Louis Mountbatten, newly appointed head of Combined Operations, quickly came to the logical solution. If the scientific boffins needed to study the thing, the British would simply go over to France and steal them whatever they needed.

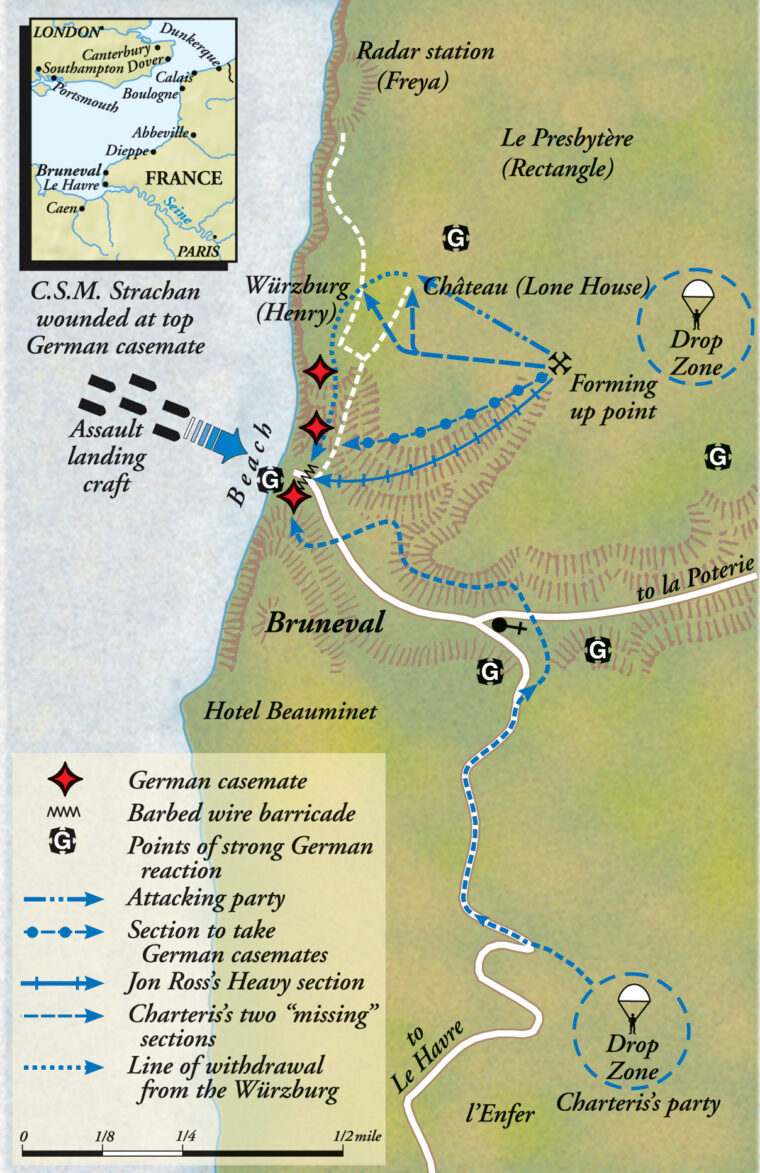

And so was born Operation Biting. While the concept was elementary—simple larceny—the execution was complex. In the first place, the objective sat on a very steep, 400-foot cliff at Cap d’Antifer, not far from a village called Bruneval. Getting there, Mountbatten decided, was best done by parachute … at night. The raiding party would be paratroopers, therefore, with an RAF radar technician going along. The RAF man would expeditiously denude the Würzberg of vital parts, while the paras fought off the enemy. Then the raiding party, carrying the booty, could be evacuated by sea.

A Difficult Heist Indeed

It did not look easy. About 400 yards away from the Würzberg and the gingerbread house, surrounded by a wood, stood a farm called Le Presbytère. It was known to be garrisoned, and there would surely be other German troops in the general area. At the base of the cliff below the German radar was a small cove with a beach, the way home for the raiders. A rugged track led from it, up a ravine to the top of the cliff, and on to the village of Bruneval. Partway up the track sat a villa called Stella Maris and a small hotel.

The Germans would be on guard and were well aware of possible danger from raiders. In March 1941 British commandos had struck the Lofoten Islands off Norway, destroying 800,000 gallons of oil and gasoline and sinking some 18,000 tons of shipping. They also brought out 300 loyal Norwegians, some German prisoners, and precious code wheels for the German Enigma encoding device. And just two days after Christmas two commando contingents landed at Vaagso on the Norwegian coast. In fierce fighting they had beaten up the German garrison and destroyed another 15,000 tons of shipping, fish-oil plants, dockyards, and other shore installations. There had also been a series of raids in North Africa, including a daring but unsuccessful raid to kill Rommel. After all of this, the Germans would surely be alert all along the French coast.

Churchill Approves!

Nevertheless, Mountbatten’s daring scheme appealed to the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who approved the idea, and the operation was on. Mountbatten’s headquarters borrowed C Company of the 2nd Battalion, the Parachute Regiment, then in training in Derbyshire. To the paras were added a troop of 12 Commando to cover the withdrawal to the beach, a Royal Engineer detachment, and the all-important RAF technician, a Flight Sgt. named Charles Cox. Cox volunteered for the mission, but he was not a parachutist, which got him a trip to the parachute training center at Ringway near Manchester.

The para company was commanded by a remarkable officer, Major John Frost. Frost came from an Army family, a graduate of Sandhurst, the British military academy, a rider and hunter. He joined his company at Tilshead Camp on Salisbury Plain and began to rehearse. Frost was a driver, pushing his men through the mud of Tilshead Camp with little time for anything but hard training and physical conditioning. Major General “Boy” Browning, the Guards officer who headed the British Airborne, inspected the strike force and told Frost to issue everybody a new uniform, for “that is the filthiest company I ever saw in my life.” Nevertheless, Browning, a strict disciplinarian, liked what he saw and directed that Frost be given whatever he wanted in equipment and supplies.

Real Objective Kept From Trainees

Frost’s men were joined by Lieutenant Dennis Vernon’s detachment of airborne Royal Engineers. Since the force would spend some of its rare free time in the town’s pubs, the paratroopers were told that they were training for an important demonstration, a practice attack on the Isle of Wight. Understandably, that notion aroused little enthusiasm within C Company, even after its men were told that if the demonstration went well a real raid into France might follow. Frost, of course, was soon told the real objective, but could not tell his men.

Also slated to go along on the raid was a soldier named Newman, a fugitive anti-Nazi German whose father had fled the fatherland for fear of the Nazis. Newman’s command of the German language might well be useful at Cap d’Antifer, and his English was perfect. He was a small, humorous, cosmopolitan man who seemed to have lived all over Europe. Frost was a bit uneasy about this unusual man, wondering whether he might be a German operative planted as a refugee by Hitler. But Mountbatten reassured Frost, and Newman would go along.

A Scotch Blend Complete With Bagpipes

While Vernon’s sappers were Englishmen, as he was, most of the infantry were Scots, largely men of the Black Watch and the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. Major Frost himself was an officer of the Cameronians. His executive officer, Captain John Ross, came from the Black Watch, as did Company Sgt. Maj. Strachan. Befitting its heritage, the unit—inevitably called “Jock Company”—even had its own piper.

Nationalities aside, the force became a tight-knit unit during the endless rehearsals for the raid. Sergeant Cox found he liked the Scots NCOs. “If you could understand half what they said, they weren’t a bad bunch.”

Cox was supposed to have another radar expert along to help him, but the man had been hurt in jump school. Cox quickly discovered, however, that Royal Engineer Lieutenant Vernon was very bright and could quickly learn enough about Sergeant Cox’s mission to take his place if something went badly wrong on the jump.

Lieutenant Vernon, Cox, and Newman were briefed on the real mission, including some instruction from radar experts, among them Dr. R.V. Jones, one of Britain’s premier scientists. Another man was also briefed on the raid, a civilian known only as “Noah,” who was in fact radar expert D.H. Priest. Far too valuable to be risked, he would travel with the landing craft and come ashore to help strip the Würzberg only if German opposition was very light or nonexistent.

Holes Cut Into Bombers’ Fuselage Serve as Jump Platforms

The unit would jump in from RAF Whitley bombers, aircraft of a squadron commanded by Wing Cmdr. Charles Pickard, a legendary combat leader who would later lead, and die in, the daring and successful ground-level deHavilland Mosquito bombing raid that shattered the walls of Amiens prison and released dozens of members of the French resistance. Pickard’s broad-winged, twin-engined Whitleys were slow, solid aircraft, which made them dependable jump platforms, but they were not designed to deliver paratroops. RAF mechanics had fixed that problem, after a fashion, by cutting some neat holes in the bottom of the bombers’ fuselages. Through them, Frost’s paras would drop straight down into the night over France.

Meanwhile, across the Channel, the French resistance had been asked for detailed information on German defense positions and troop strength around Cap d’Antifer. Famed underground leader Gilbert Renault—code name “Remy”—received London’s signal on January 24, 1942. It asked for details of the coast defenses around Cap d’Antifer, especially machine-gun positions; for information on the German units in the area, their strength and reputation; for the places in which the German garrisons were quartered; and for the locations of barbed wire.

French Resistance Provide Ground Assistance

Remy called on two of his most experienced French agents, code named “Pol” and “Charlemagne,” and they went down to the Bruneval area and looked around. Posing as agricultural engineers, they learned that there was a small garrison commanded by an efficient sergeant quartered at the Hotel Beauminet on the edge of the village of Bruneval. At the Le Presbytère farm was a force of about a hundred men whose job was to man 15 defense positions along the edge of the cliff.

There were also other units in the general area. An infantry regiment and an armor battalion were close enough to intervene if Frost’s men did not carry out their mission swiftly. The Frenchmen engaged in conversation with a German sentry, who obligingly let them take a walk on the beach. It was, they discovered, not mined, but they could see at least two machine-gun positions along the track to the beach. The road was blocked with a thicket of barbed wire, but there did not seem to be any wire anywhere else. Pol and Charlemagne thoughtfully visited an inland hotel as well, partook of a sumptuous black market dinner, and copied from the register the names of visiting German soldiers. Back in Britain, these names would be matched with unit rolls; British intelligence would soon know which German outfits were in the area.

British Build Detailed Model From French Intelligence

The agents returned to their boss, and Remy got their information out to England. From aerial photos and the French agents’ very detailed information, British craftsmen put together a detailed model of the target area in the basement of a secure house.

British security was very tight indeed. The important features of the objective area all received code names: the radar was called “Henry,” the gingerbread house was “The Lone House,” Villa Stella Maris was “Guardroom,” and the garrisoned farm of La Presbytère was christened “Rectangle.” These names were used throughout training. The raiders would not know their actual destination until just before takeoff. Whenever the paras moved outside Tilshead Camp or Loch Fyne, all identification was removed from their uniforms, including their jump wings. When the Whitleys finally headed across the Channel to drop their sticks of paras on the French coast, they would fly as part of a larger formation of bombers.

In addition to training hard at Tilshead Camp, the infantry and sappers spent some time in Scotland, at Inveraray on Loch Fyne. There, they were quartered aboard HMS Prins Albert,a 22-knot ex-Belgian vessel converted into an armed assault transport. Frost’s men learned the fine art of getting themselves and their gear in and out of landing craft, intact and at high speed. Assuming all went reasonably well on the raid, the paras would be collected from the beach by some of Prins Albert’s eight LCAs (Landing Craft Assault). The 40-foot LCAs could carry 35 men, and drew only 21/2 feet of water.

Forming Operation Biting’s Landing Party Teams

Major Frost divided his men into teams, each one named for a British naval hero. Captain Ross would lead team “Nelson,” occupying the beach, receiving the landing craft, and helping to cover the withdrawal. Lieutenant Euan Charteris—called “Junior”—would lead another party to take out Villa Stella Maris. The French underground agents had confirmed that the villa contained a machine-gun emplacement. In addition to the garrison at Le Presbytère—perhaps a hundred men—and the 10-man guard on the beach road, there were at least another 40 Germans in Bruneval itself.

Up on the cliff, Frost himself would lead team “Hardy” against the gingerbread villa behind the radar in its shallow pit. They would cover team “Jellicoe,” led by Lieutenant Peter Young (later one of the most famous Commando leaders), at the Würzberg itself. Team “Drake,” commanded by Lieutenant Peter Naumoff, would hold off any Germans coming from the direction of the garrisoned farm at Le Presbytère. “Rodney,” under Lieutenant John Timothy, had the mission of defending in the direction of La Poterie. The troops were armed with rifles, grenades, Sten guns, and Bren light machine guns. The officers carried American Colt .45s, a much-coveted pistol in the British forces.

Hurry Up and Wait: the Bruneval Raid was Good to Go

Rehearsals for Operation Biting over, the troops packed their gear on February 23, 1942, and then, in a dismal routine familiar to every soldier in every army, they waited. The weather had turned sour and stayed that way. For three more days Frost’s troopers prepared to go each morning, then stood down each evening about teatime as the weather continued foul. By the 27th, Major Frost had about decided that the evil weather had delayed the mission for at least a month, for very soon the operation would have to be mounted on an ebb tide.

Nevertheless, late in the afternoon the word came down—the Bruneval raid was a go. Although there was a foot or so of snow on the ground in France, there was no wind to speak of, and a bright moon shone with just a little haze. From Portsmouth HMS Prins Albert moved to sea, carrying 32 men of Number 12 Commando. Destroyers Blencathraand Fernie,and five motor gunboats (MTBs) would cover the operation. In hutments around the edge of Thruxton Airdrome, Company C and its sappers filled themselves with bully beef sandwiches and tea laced with rum. Altogether, there were six officers and 113 “other ranks,” as the British say, which included nine sappers and four signalmen. Now Frost was finally able to tell his men precisely where they were bound.

A Rough Flight Made Bearable With Tea, Rum and Song

Boarding the Whitleys was a cumbersome business, the men loaded with parachutes, weapons, grenades, and ammunition. No paratrooper is ever comfortable on a flight, and this one was no exception. Old troopers contend—correctly—that men make parachute jumps to get out of the bloody airplane. The Whitley was grossly uncomfortable: The men sat on the metal floor, trying to avoid the ribs of the fuselage. The airplane was very cold, especially after the cover was removed from the jumping-hole in the bottom of the fuselage. Many of the men climbed into sleeping bags or wrapped themselves in blankets for warmth. At least one canteen of tea and rum made its way on board and was passed from hand to hand.

Still, they were cheerful—the mission they had waited for so long was at last under way. Some men sang, after the custom of the British Army, “Annie Laurie” and “Red River Valley.” Sergeant Cox soloed on “The Rose of Tralee,” an Englishman singing an Irish song for Scots soldiers. Other paras played cards, after the fashion of every army. One Corporal Stewart won most of the money, as he generally did, but genially assured his comrades that if he were killed on the mission they could get their money back.

Despite Enemy Flak and Dark of Night, Jump Goes Well

As the black-painted Whitleys crossed the Channel coast into France, German flak erupted all around them, directed, ironically, by the very radar that was their target. But no aircraft were hit, and within an hour from take-off the Whitleys dropped their 10-man sticks into the night over France. Airborne operations at night, even in moonlight, are notorious for scattering troops over several acres, but this night most of the paras hit the drop zone accurately, landing in a foot of snow and quickly rallying in a treeline about three-quarters of a mile from the objective.

Apparently the first order of business was answering a collective call of nature, the hot tea consumed in quantity at Thruiton demanding to be let out. Only Lieutenant Charteris and his 20 men of Captain Ross’s group were missing somewhere in the night. They had, in fact, been dropped far away to the south in the wrong valley, after the Whitleys carrying Charteris and his men had been driven off course by accurate German flak.

Initial Attack Catches Germans Off Guard

Frost could not wait and put in his attack on the Würzberg site and the Lone House. At the shrill squeal of Frost’s whistle, the paras went in against “Henry” under a shower of hand grenades and automatic fire, and the remnants of the Luftwaffe crew ran for it. One ran the wrong way and fell over the edge of the cliff. Dragged back by a para, he became a prisoner, along with one other German. Both men were questioned by the paras, but were “almost incoherent with surprise and shock.”

Flight Sergeant Cox and Lieutenant Vernon promptly went to work on the radar, interrupted by German fire from Le Presbytère, which killed one para outside the Lone House.

The Lone House turned out to have only a single German soldier in it. He was firing at the force attacking the radar site when paras broke into the house and shot him down. Meanwhile, a German captured at the Würzberg site was being interrogated by Newman and could not talk fast enough. Yes, he said, there were about a hundred more Germans up at Le Presbytère, and they had mortars. He also acknowledged that the radar had been tracking the Whitleys as they came in over the French coast. Afraid of bombs, they had shut down as the RAF aircraft appeared overhead.

Still Warm German Radar Set Discovered

The radar set was still warm; it had obviously been operating quite recently. Cox and Vernon were busily making drawings of the apparatus and making scribbled notes (the photography stopped when the Germans opened fire on the flare of the flashbulbs). They found the set to be on wheels and well designed, its dish about 10 feet across, all of its vital works in a metal box about five feet by three. As they worked, one of the sappers used a cold chisel to knock off and collect the metal tags with which the thorough German makers had labeled everything.

Vernon found they could not quickly get the aerial unit loose, so he set another of his sappers to sawing it free. He and Cox got the pulse unit and amplifier loose easily enough, then discovered that even their longest screwdriver would not reach the screws holding the machine’s transmitter. The solution was a crowbar. As they pulled on the vital part, one of the sappers put his weight on the bar and the transmitter tore loose with part of its frame. The piece of frame, as it later turned out, also carried an important switching unit vital to the set’s operation.

Germans Mount Fierce Counterattack

Down on the beach, Captain Ross’s handful were held up by rifle and machine-gun fire from positions close to Villa Stella Maris. Frost could see German flares shooting into the sky from that direction and hear heavy firing down the hill. In the din he could distinguish a Bren gun shooting back at a heavier German automatic weapon. The Germans at Le Presbytère seemed to be forming up for a counterattack. German fire grew heavier, and on the clifftop another para had been killed. A pair of German bullets hit an element of the radar set as Cox held it in his hands.

In addition to the Germans at Stella Maris and Le Presbytère, the British were now faced with a platoon from a company of the German 685th Infantry Regiment, coincidentally returned to its quarters in La Poterie after maneuvers. This force was now on its way to Bruneval. Worse, the German positions along the cliff face were still active; the paras’ “Rodney” group was too small to clear out the defenders. There was also a roar of firing over toward Bruneval village itself, and Frost knew it was high time to leave.

Cox and Vernon having finished their job, Frost began to pull back down the ravine to the beach, hauling the liberated German radar parts on a sort of two-wheeled canvas cart, thoughtfully brought along for the purpose. Along the way, Company Sgt. Maj. Gerald Strachan went down with three bullets in the belly, and card-playing Corporal Stewart was wounded in the head. As he had promised, he gave his wallet to a comrade, but the other Scot, examining Stewart’s head, saw that the hurt was, in his words, “only a wee bit of a gash.”

“Then,” said Stewart, “give us back that wallet.”

Teamwork Fends Off Germans

At the top of the hill, Lieutenant John Timothy’s rear guard was holding off the Germans, who had already reoccupied the Lone House. Since the way to the beach was still swept by German fire, Frost ordered the party with the wounded and the precious trolley cart to wait on the trail short of the beach. Frost then turned back toward the top of the cliff to help out John Timothy’s rear guard, taking with him a mixed force of infantrymen and sappers. His men and Timothy’s drove off a half-hearted German counterattack, and Frost hurried back toward the beach. Down below, Ross’s men had pulled the knife-rest barrier away from the wire barrier along the beach, and Lieutenant Naumoff was preparing to lead a charge against the German positions above them.

About this time, however, the situation improved dramatically, for Euan Charteris and his little force appeared out of the southeast, having run two and a half miles through the darkness. He and his men had moved through a unit of German troops in the gloom, and one of the enemy fell in with the British, obviously thinking they were his own people. As the official history dryly put it, “Subsequent explanations resulted in the death of the German.” Along the way Charteris’s little band had lost several men, strayed in the darkness, but the lieutenant could not wait for them.

At last Charteris caught sight of the Cap d’Antifer lighthouse and at once knew where he was. Near Bruneval itself, Charteris was seen by the German defenders, but his men shot their way past the little hamlet and trotted on toward the coastal track that was their objective.

A Racket To Raise the Dead and Annoy a German Commander

Now, clearing the village, Charteris led his men quickly downhill, and they came storming out of the night, yelling like banshees. It was too much for the German defenders, and Charteris overran the German machine-gun positions, rushing the house behind two volleys of hand grenades. One German surrendered at the villa, a telephone operator who still clung to his handset. He had, he said, been talking to his commander, who was most unhappy with all the noise on the telephonist’s end of the line. Charteris’s men, with the men of “Rodney,” then cleared the German posts overlooking the road. The way to the beach was open, and just in time. Frost got his wounded—Strachan, Stewart and four others—and the precious radar parts down to the water’s edge.

Now the problem was getting off the beach. Offshore, three of Prins Albert’s LCAs were waiting to come in, covered by the three MTBs. Frost was having trouble contacting them with the paras’ relatively primitive radio sets, however, and time was running out. From the clifftop, Timothy reported seeing headlights approaching. Frost now tried a pair of green flares, fired from a Very pistol, but still got no answer. As a last resort, he activated a small radio beacon called “Rebecca,” so classified that it came with its own integral destruction device. Its corresponding set, “Eureka,” was in one of the LCAs.

“God Bless the Ruddy Navy!”

But the Navy had seen Frost’s flares and a light signal and was on the way in. Waiting had not been easy for the little boats either. The weather was getting worse and worse; the LCAs had narrowly avoided being spotted by German destroyers and E-boats as they waited for Frost’s signal, and the tide was on the ebb. But now they were coming, all of them, and on the beach a voice cried out, “God bless the ruddy Navy!” As the boats neared the shore, Bren gunners on board opened fire. Frost and Ross ran into the surf, not realizing the fire was directed at the clifftop, waving at the gunners to stop. “We thought you was a Jerry with a suicide wish, but we gave you the benefit of the doubt,” said a voice on board one of the LCAs.

Frost’s men got aboard the LCAs in record time, tenderly loading their wounded as German fire plunged down from the clifftop. The paras and commandos on the LCAs—men of the South Wales Borderers and Royal Fusiliers—drenched the German positions with covering fire. The first LCA took the wounded men, Cox, the sappers, and the loot from the WürzbergThis boatload—which included “Noah”—was immediately transferred to one of the MTBs, which immediately left at high speed for England. Priest was already eagerly examining the loot from the German apparatus while the MTB was still at sea.

Raiders Receive Enthusiastic Welcome Back Home

The other MTBs took the remaining landing craft in tow, and the little flotilla headed back for safety through high winds and heavy seas. They were covered by two Royal Navy destroyers, RAF Spitfires, and four light destroyers of the Free French Navy. There was no German interference. As the little flotilla neared Portsmouth, the raiders won a salute from the escorting destroyers, and an enthusiastic welcome awaited them back at their base from Pickard and his pilots.

Frost’s daring raiders had come home with the key to the Würzberg radar, saving untold numbers of RAF aircraft and airmen. They had paid for their success with only two dead and two wounded, plus six men who had become separated from their comrades and were eventually captured by the Germans. German losses were five dead, two wounded, and five missing—two of whom made the one-way trip to England as British prisoners. To add insult to injury, the next day a prowling Hawker Hurricane fighter spotted a group of German officers inspecting the site of the raid; the Germans ended up somewhat ingloriously at the bottom of the empty hole where their Würzberg had been, hiding from the fighter’s eight machine guns.

A handful of airborne soldiers had been responsible for a major turning point in the scientific war, in a raid that Admiral Mountbatten rightly called “one hundred percent perfection.”

British Raiders Praised From Both Sides

A German report of the raid agreed. “The operation of the British commandos was well planned and was executed with great daring. During the operation the British displayed exemplary discipline when under fire. Although attacked by German soldiers they concentrated entirely on their primary task.”

Frost and Charteris both received the Military Cross; Lieutenant Young was Mentioned in Dispatches. Sgt. Maj. Strachan, who recovered from his wounds, won the French Croix de Guerre. Military medals were awarded to Sergeant Cox and two other NCOs.

Frost went on to command, with great distinction, the battalion that held the vital bridge at Arnhem against great odds during Operation Market-Garden. He retired long afterward as a major general. Peter Young participated in action after desperate action, commanded 3 Commando on D-day, and finished the war as a brigadier. Sadly, the gallant Charteris was killed before the year was out, fighting in North Africa. Sergeant Major Strachan, wounded again at Arnhem, died in 1948, only 42, from what were probably complications from his wartime wounds. Newman was captured during the successful commando strike at St. Nazaire in March 1942. His cover story was so good, however, that he was never identified as German. He became a successful businessman in Britain after the war.

Operation Biting Yields Immense Technological Advantage for Allies

With Operation Biting, a handful of airborne soldiers had given Britain an enormous advantage in the critical radar war, providing the means for British scientists to further develop radar countermeasures, including “window,” the strips of tinfoil that badly confused German radar through the latter part of the war.

Fifty years on, Royal Air Force Group Captain Lord Cheshire, himself a winner of the Victoria Cross, wrote Frost in remembrance and congratulation. He pretty well summed up the almost incalculable benefits of the Bruneval raid. “Our own [the RAF’s] op on the night of 5th/6th June 1944 could never have succeeded as it did had we not been able to test out the window sizes and the tactics on the radar set itself, and that is quite apart from the help it gave the boffins in developing window as a whole. We wartime aircrew have a great deal for which to thank you and those under your command….”

”… Major Frost Sent a Great Shock Through Hitler’s Headquarters.”

Cheshire’s high praise was echoed from an unexpected source, well after the war was over. General Kurt Student, who in his own right knew a thing or two about airborne operations, wrote Mounbatten to say, “To take the Bruneval Station is a ‘coup de main’ from the air. This was a grand plan, just to my liking as the creator of the German paratroopers.… The successful execution by Major Frost sent a great shock through Hitler’s headquarters.”

It did indeed. Hitler raged at his own commanders, demanding that the “Brandenburg Division,” a unit created for special operations, go to England and bring back a British radar unit.

He waited in vain.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments