By John W. Osborn Jr.

“I am not a collector of deserts,” Mussolini declared regarding his imperial ambitions. Instead, he would be a loser of them, most publicly in North Africa and, in one of World War II’s least-known campaigns, in East Africa. There, a towering prince, a diminutive emperor, generals of widely different temperaments, an officer with the messianic fervor of a Biblical prophet, and even an American society jewelry salesman would fight for control of the barren wastelands of Eritrea, Italian Somaliland, and Ethiopia, which passed for Italy’s pitiful excuse for an empire.

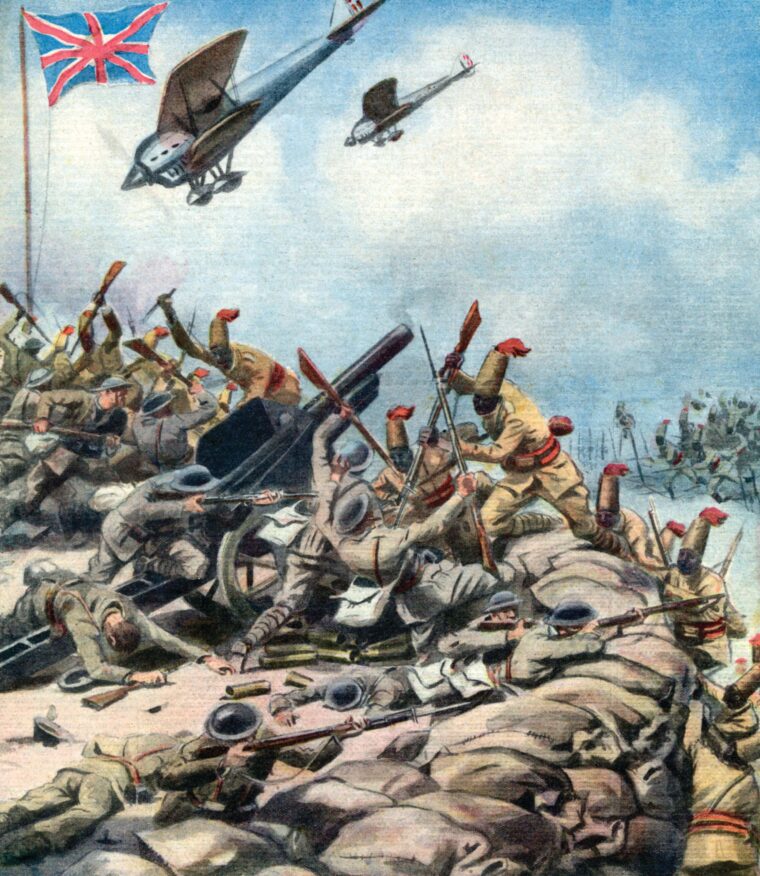

To Mussolini’s son-in-law, Foreign Minister Count Galeazzo Ciano, the declaration of war with Britain in June 1940 was “the chance of 5,000 years” to expand Italy’s African empire by grabbing British Kenya and Tanganyika. The numbers to do it clearly favored the Italians: 92,371 Italian troops including the crack Savioia Grenadiers and the 11th Legion, the best Blackshirt formation, 250,000 Eritrean, Amhara, and Tigrean troops led by capable Italian officers, 323 aircraft, mostly bombers, and almost 200 armored cars and tanks.

In contrast, the British had only 19,000 troops in the region, and almost all were colonial, along with only a half dozen aircraft of 1928 vintage, a few homemade armored cars, and no artillery. British forces had a standing order to “fire at anything more than one aircraft” since they would have to be Italian. The British had only one serviceable carburetor for their own airplanes.

“Victory is Our Cry!”

The Italians first struck at Britain’s own parched pieces of East Africa. In July 1940, approximately 8,000 Italians and Eritreans invaded eastern Sudan, opposed by just 500 men of the Sudan Defense Force (SDF), capturing the frontier posts of Kassala and Gallabat. The next month, 25,000 Italians, Amharas, and Eritreans with armor and massive air cover drove a tenth of that number of British, Indians, and Africans out of British Somaliland in a Dunkirk on the Red Sea.

”Victory is our cry! We set off like arrows from the bow,” an Italian soldier exulted. But other numbers told of the ferocity and tenacity of the British defenses: 500 Italian dead to only a dozen SDF, 2,029 Italian casualties to just 250 for the British in Somaliland, where Captain E.C.T. Watson earned the Victoria Cross leading, despite serious wounds to his left eye and right shoulder, the defense of his hilltop position for four days until overrun and captured.

Mussolini had gambled on a quick end to the war once France fell, saying, “It will be sufficient if the Empire holds out for three months.” Once it was clear the war would go on, and with the closure of the Suez Canal isolating East Africa, morale among the Italians sank and a defensive mind-set took hold.

The demoralization started at the top. The Viceroy of Africa Orientale Italiana since 1937, Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, was most imposing when he was standing—he was 6 feet 4 inches. He had hoped to avoid war in the first place, telling a British official in Cairo, “Don’t take literally all that Mr. Brown [Mussolini] says.” Count Ciano was to eulogize him as a “noble figure of a prince and Italian, simple in his ways, broad in outlook, humane in spirit,” which meant he was as miscast for a leader under siege as he was a Fascist overlord.

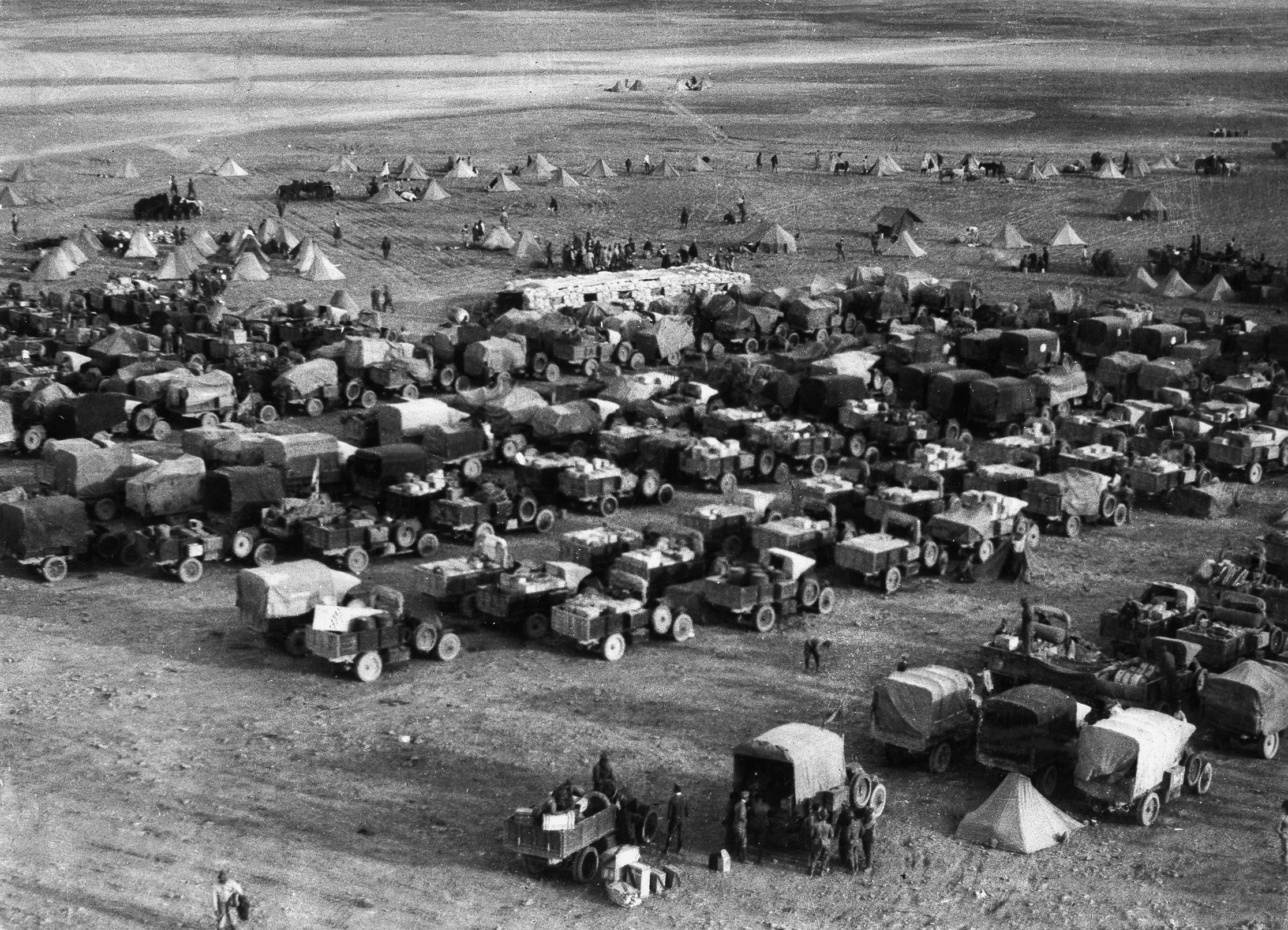

While the British were building up in the theater with Worcestershires, Cameron Highlanders, Royal Sussex, West Yorkshires, Highland Light Infantry, Royal Fusiliers, the 4th and 5th Indian Divisions sent from the Middle East, 33,000 raised in East Africa, 9,000 from the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and Nigeria in West Africa, 27,000 from South Africa, a unit of Palestinian Jews, even the French Foreign Legion, they were winning their first victory of the campaign thousands of miles away in Britain.

The code-breakers of Bletchley Park had cracked the Italians’ high-grade cipher for East Africa. “Throughout the campaign, from the first day, every secret Italian operational order sent to, or from, the Italian viceroy was picked up as it was issued, and used to foil whatever plan had been made, or to exploit whatever weaknesses had been revealed,” wrote historian Martin Gilbert. Yet, pushed forward too early under intense pressure by Secretary of State for War Anthony Eden and Commander-in-Chief, Middle East, General Sir Archibald Wavell on a visit to Khartoum, the first British offensive in East Africa and of World War II was to end in disaster.

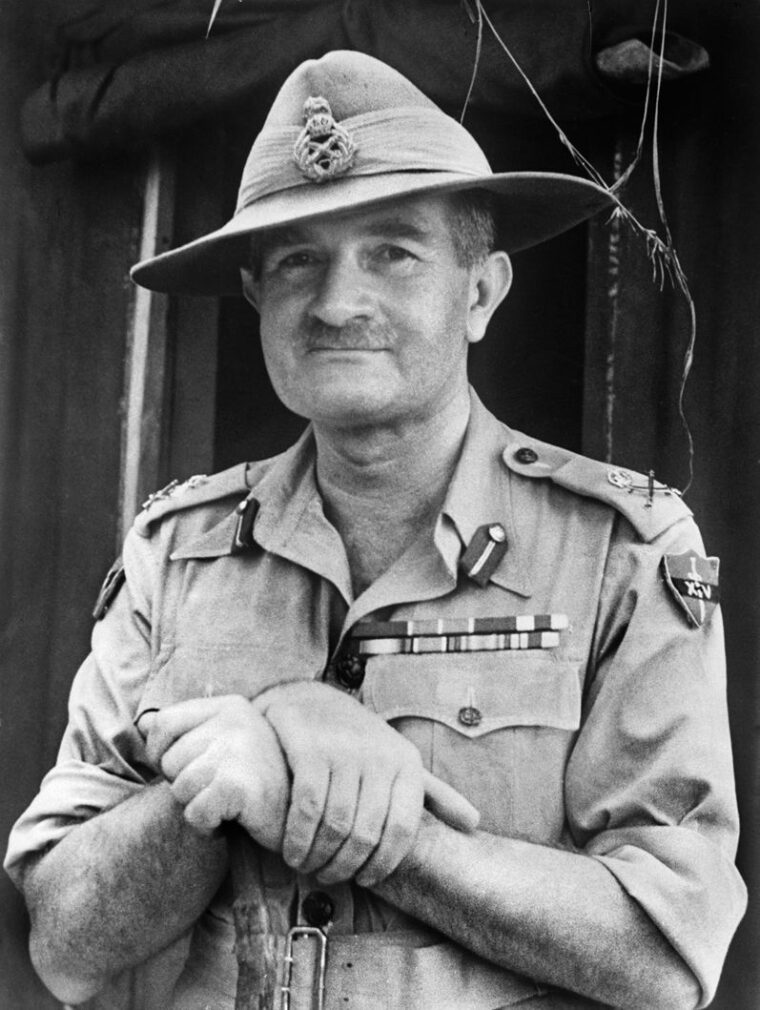

Seven thousand troops led by Brigadier William Slim aimed at retaking Gallabat, then driving into Ethiopia. Slim, who behind his tough exterior had the touch of a poet, described the dawn before the assault, on November 6, 1940. “To the east the hills behind Gallabat, Jebel Negus and Jebel Mariam Waha began to show up as dark and distant silhouettes against the first pale lemon wash of sunrise. Gently, the lemon deepened to gold and changed to soft luminous blue, but the hill of Gallabat remained invisible, sunk in the blackness of the further hills.”

The attack was initially successful. An Italian captain presented to Slim complained, “As soon as your bombardment started he [his commander] rushed out crying, ‘to the walls, to the walls’ and disappeared toward the border. He has not been seen since!”

But the tide turned when the Italians shot down five British Gloster Gladiator fighters, then bombed and strafed the British lines. Narrowly missing being killed by machine-gun fire, Slim walked to the front to be told by an Indian officer, “British soldiers from Gallabat are driving through my post, shouting that the enemy are coming and the order is to retire. We cannot stop them; they drive fast at anyone who tries!”

“Nonsense,” said Slim. “They must be empties coming back to refill. You must have misunderstood what they said.” To Slim’s shock, two trucks roared past, British soldiers in them shouting the enemy was coming.

Slim tried another attack the next day but called it off when some shells fired by the Italians caused the British, mistaking the smoke for gas, to again flee. The final British losses were 42 killed, 125 wounded.

“The last great European-led cavalry charge in Africa”

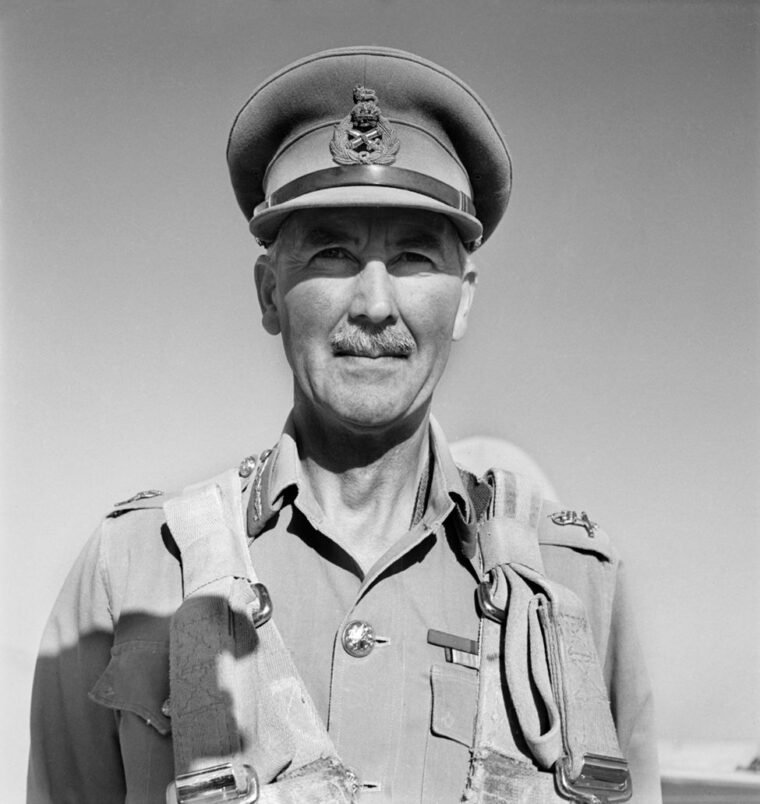

The British shifted their next offensive north, toward Eritrea. Commanding Gazelle Force, which included SDF, Indian, and British troops, was Maj. Gen. Sir William Platt, whom no one would call poetic. A high-ranking official in the Sudan administration said he was “as aggressive as they make ‘em, a regular little tiger, a fine upright fiery (often testy) capable soldier.”

Aware that the Duke of Aosta had ordered withdrawal from Kassala and Gallabat, the British struck on January 19, 1941. The Italians laid minefields to slow pursuit, and Lieutenant Perminda Singh Bhagat won the Victoria Cross for probing and defusing them, wounded three times in the process.

The Italians made a stand on the hills above the Keru Gorge. An Italian lieutenant even led a cavalry charge of 500 men into machine-gun and artillery fire, with 179 riders killed and 260 wounded. Of the horses, 89 were killed, 68 wounded.

“It must have been the last great European-led cavalry charge in Africa,” wrote Anthony Mockler in his book Haile Selassie’s War. “Churchill, who himself in his youth had charged with the 8th Hussars at Omdurman, would have approved.”

The Battle For Keren

After three days of fighting, the 5th Indian Division led by Slim, moving from the south, took the Italians in the rear, forcing them to flee by night eastward toward what would become the site of the costliest and most decisive battle of the East Africa campaign—the town and 4,300-foot-high, 150-mile-long plateau of Keren. The fighting began on February 2, 1941, and continued until March 27. Twenty-three thousand Italians and colonial troops roared down the key Dongolaas Gorge, confronting 30,000 British and Indians in some of World War II’s most hellish but little known fighting.

“What was ahead was a hard positional battle—a miniature Passchendale, with heat substituting for mud,” Colonel A.J. Barker, an officer who served in the East Africa campaign, later wrote in Eritrea 1941. “Men who were at Keren, who served subsequently in other theaters of war —on other battlefields, in Italy, Burma and North-West Europe where conditions have been described as ‘bloody’, ‘appalling’ or just ‘frightful’—have said that nothing—NOTHING— was worse than Keren.”

Just to reach the plateau, the British and Indians had to cross through a killing ground that the British with grim humor called “Happy Valley,” driving through intense Italian fire from above. “The whines of the approaching shells were usually lost in the noise of engines as the trucks bumped over the sand stretch of ground in low gear, but their dull crump could be heard as they exploded on striking the ground and the splashes made by their splintering metal were clearly visible in the sandy surface,” wrote Colonel Barker. “It was, he added with understatement, “a soul shattering prelude.”

Once on the crucial Cameron Ridge, British soldiers quickly “looked like Black and White Minstrels,” Colonel Barker wrote in those pre-politically correct days, “the black dust vomited into the air by exploding mortar bombs settling on sweating skins to leave only white slatey lines round eyes and lips.” They had to inch their way up the plateau in the face of machine-gun fire and thousands of grenades dropped on them. Fighting was often hand-to-hand with rifle butt and fist. On the 41st day, the British captured the critical Dologoroc peak east of the gorge, then held off seven Italian counterattacks, one stopped 80 yards short of the command post. British and Indian losses on Keren would ultimately be 536 killed and 3,229 wounded.

One of those killed, Subadar Richpal Ram of the Rajputana Rifles, led a charge, shouting Rajput war cries, when his company commander fell wounded. Ram directed the defense of a position through a night of savage fighting and was leading another attack when he finally fell; he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Of the Italians, veteran Donald Bateman, who later also fought at Monte Cassino in Italy, said, “No German paratrooper on Cassino fought more determinedly than the Italian soldier on Keren. There is no doubt in my mind, from experience of both, that Keren was the tougher battle.” Losses among the Italians (their colonial ones are unrecorded) were 3,000 killed, 4,500 wounded.

Italian war correspondent Renato Loffredo described a determined night counterattack by Savoia Grenadiers and Askaris on Cameron Ridge. In the freezing cold, the Italians crept silently toward Indian positions, then began throwing grenades. The Indians opened machine-gun fire in response as the fighting became desperate and confused in the darkness.

“The Indians were unable to close their ranks,” an Italian soldier later told Loffredo. “The fighting became man to man. Rifles were used like clubs. The Indians advanced swinging them about their heads. A group of askaris found themselves in a group of Scots, tall, robust, and strong. One Scot, stunned by a hand grenade, found two grenadiers on top of him who finished him off … a terrible Scot sergeant advanced, firing his gun in two powerful hands with the butt in his stomach. A grenade stopped him. A second arrived. The first exploded between his feet, the second on his chest.”

But the Scots stood their ground. “They held light machine guns like rifles and fired rapidly and powerfully, cutting down everything in front of them,” Loffredo recorded. Finally, the Italians had to escape back into the dark.

“We Didn’t Want This War”

The plateau itself also made Keren the nightmare of World War II for anyone who was there. Without a stick of shelter and a limit of a pint of water a day in the scorching heat, the soldiers’ fingers blistered at the touch of rock, and their tongues blackened and became swollen. Dysentery was rife, but there were no latrines. Bodies fell and garbage and excrement were dumped into the ravines, attracting dense clouds of flies and more disease.

With the terrain too rugged even for mules, a company from each British battalion had to be diverted to carry up every bullet, drop of water, and scrap of food. It would take a dozen men to carry one wounded comrade down. The rattle of machine-gun fire and thump of explosions were sometimes interrupted by the strains of Verdi arias broadcast over British loudspeakers along with news of Italian disasters in North Africa in an early attempt at psychological warfare.

General Platt had predicted that Keren “will be won by the side which lasts longest…. And I promise you that I will last longer.”

Finally, Indian engineers blasted through the Dongolass Gorge and armored cars rolled into the town of Keren to find it abandoned. The retreating Italians “were so exhausted and dispirited that sometimes they did not even move off the road when strafed,” a South African pilot reported. The Foreign Legion finally cut the road, bagging 1,000 prisoners, a platoon led by the onetime American jewelry salesman Lieutenant John Hasey alone taking 300.

Before joining the Free French and its Foreign Legion unit in London, Hasey had worked at Cartier in Paris with the Duke and Duchess of Windsor among his clients, then as an ambulance driver for Finland in the Winter War against Russia. Earlier in the campaign, he had met some other Italian prisoners and gotten a strange request: “Whenever you see an Italian over 40 years old, shoot him. Don’t take him prisoner.”

When Hasey asked why, he was told: “Because they’re responsible for all this. It’s their war, not ours. They put Mussolini in power. We didn’t. We didn’t want this war. We didn’t want to fight you; but we were stuck with it. We couldn’t get out of it. We were forced into the army.”

Massawa Captured: A Victory For Lend-Lease

The Duke of Aosta had made his own prediction before Keren, that if it was lost, “everything will crumble.” Asmara, capital of Eritrea, surrendered without a shot five days after Keren’s fall. General Platt cabled British officers in Khartoum, capital of the Sudan, that his message of victory was “not, repeat NOT, an April fool.” A week later the port of Massawa fell after its main defense, Fort Victor Emmanuel, was stormed by the Foreign Legion.

Taking part in the assault was French Foreign Legionnaire John Hasey: “Machine-gun emplacements were on all hills approaching the Fort, and our first mission was to clean them out one by one. My platoon advanced through its assigned sector with bayonets fixed. As machine-gun emplacements identified themselves by fire, they were surrounded and isolated. Legionnaires crept inexorably upon them. My command was falling all around me, but somehow I seemed to be spared. We moved closer and closer to the fort.

“My platoon, or what there was left of it, was the first to reach the top of that hill, the first to scale its walls and drop inside, and perhaps the first to take the heart out of those Italians. Until then, they fought well, but now they no longer had stomach for it.”

Hasey took another 300 Italians prisoner, and in one of the cruel ironies of war, the nine Italians in the Legion died fighting their countrymen in Eritrea. Hasey soon learned that he and others of his unit had been condemned to death by the pro-Nazi Vichy regime in France; in true Legion fashion, they toasted the announcement with captured Italian wine. The capture of Massawa proved to be the great strategic prize of the East Africa campaign. The British had a new port and route to deliver supplies to the Middle East and, in Washington, D.C., President Franklin D. Roosevelt could proclaim the Red Sea a nonbelligerent area, allowing Lend-Lease supplies to transit through it.

The Mad Orde Wingate

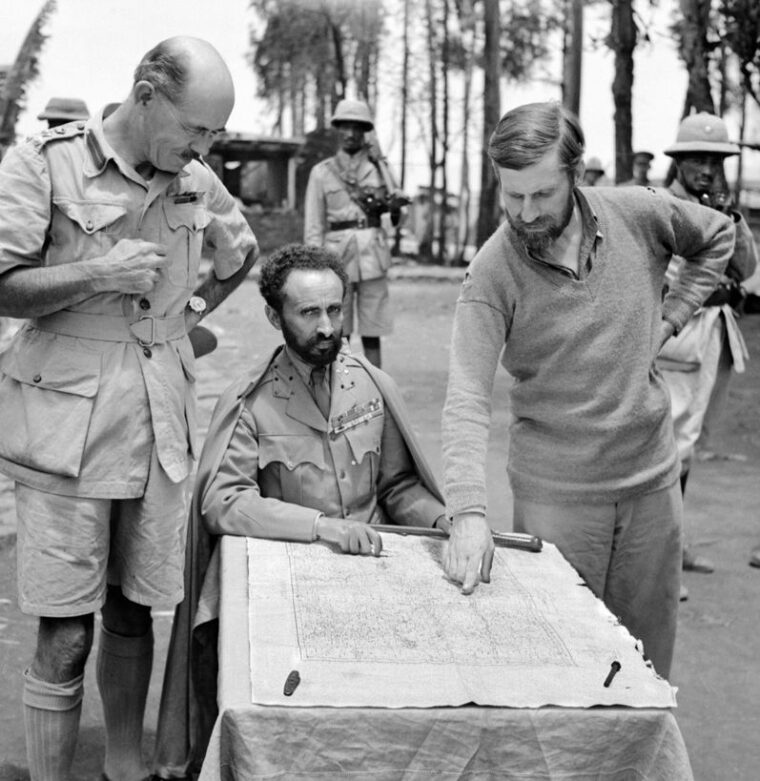

In four months the Italians had lost their oldest colony, 65 battalions, 40,000 prisoners, and 300 artillery pieces. The end of their newest colony had simultaneously been effectively sealed. Two weeks after Mussolini declared war, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie began a nine-day flight from England, including a risky overflight of newly occupied France, to Khartoum after a four-year exile from East Africa. Perhaps the only man at 5 feet, 4 inches who could be called imposing, he was back to reclaim the throne he had risen to through civil war and Byzantine court intrigue, then was driven from by Mussolini. With the Foreign Office in London ambivalent and the British colonial administration in Khartoum hostile, he found a fervent ally in the officer sent from Cairo to liaise with him and organize guerrilla operations in Ethiopia.

Openly contemptuous of “the military ape,” as he liked to call the average British officer, Orde Wingate was considered either a genius, a mad genius, or simply mad, depending on who was being asked. In Khartoum he provided ammunition for all sides as he argued for the kind of long-range penetration operation he would perfect in Burma, criticized Platt’s strategy to his face, insulted Platt’s officers, and greeted visitors stark naked, brushing his body and snapping at flies with a towel, even if one alit on the visitor’s shoulder. He told Haile Selassie he “should take as his motto an ancient proverb found in Gese, ‘If I am not for myself, who will be for me?’ and trust in the justice of his cause.”

On January 20, 1941, a transport plane landed Haile Selassie and Wingate on a dry riverbed on the frontier between Sudan and Ethiopia, where they held a small ceremony proclaiming the emperor’s return, ran up Ethiopia’s flag, and drank a toast in warm beer. The prospect of facing more than 30,000 Italians with only 50 British officers, 20 British noncommissioned officers, 800 Sudan Defense Force men, and 800 Ethiopian patriots did not concern Wingate in the slightest.

“Given a population favorable to penetration, a thousand resolute and well-armed men can paralyze for an indefinite period, the operations of 100,000,” he said. To show his certainty about the outcome, he renamed his operation from Mission 101 to Gideon Force, after a Biblical commander who defeated 15,000 with only 300.

“We found ourselves in a strange world,” a young captain in Gideon Force, William Allen, was to write. “The experience recalled old tales like King Solomon’s Mines.” Gideon Force had to trek across western Ethiopia through thick scrub and rocky, thorny wadis (the emperor more than once putting his shoulder to a truck), climb a 3,000-foot rock wall to a plateau, and endure heat, a shortage of water, jaundice, dysentery, malaria, and parasite flea infections. Dense clouds of flies hovered overhead. Camels died at the rate of over 50 a day. Vultures so fattened themselves on the carcasses that they stumbled about, too heavy to get airborne.

Captain Michael Tutton recalled, “The milling camels. The whistling wind. The black slopes of the mountain lit up by the fire. Teeth chattered.” Through it all, William Allen wrote that Wingate “never spared his own body…. Some demon chased Wingate over the highlands…. His pale blue eyes, narrow-set, burned with an insatiable glare. His spare, bony, ugly figure with its crouching gait had the hang of an animal run by hunting yet hungry for the next night’s prey.”

The terrain would prove a more formidable obstacle than the Italians. “The vivid imagination of the enemy was always ready to picture a company as a division for the first two days following its appearance, ” Wingate reported. “It was essential to maintain the momentum of surprise, if benefit were to be obtained from his credulity and cowardice.”

“Clear Out as Quick as You Can”

Wingate panicked the Italians with moonlight sniping of sentries and grenade-tossing raids from out of the night. Allen took part in one attack. “A mortar fire, maintained during the night, was directed against the fort, and by the morning the majority of the buildings within the fort area were burning. Machine-gun and mortar fire was continued against the fort throughout the whole of the second day; while from time to time native propagandists from loud-speakers harangued the Colonial troops within. The morale of the garrison of the fort began to sag as deserters began to find their way to the Patriot bands covering the road against any breakout to the west.”

With little resistance, the Italians abandoned position after position and finally fled from the provincial capital, Debra Markos.

Wingate was inspecting the empty Italian headquarters in Debra Markos with correspondent Edmond Stevens of the Christian Science Monitor when the phone rang. “You speak Italian. Take the call,” Wingate told Stevens.

“But what shall I say?” Stevens responded.

“Say that you’re the doctor [an Italian doctor had stayed to be with his wounded]. Tell them the British have captured Debra Markos and a division 10,000 strong is heading for the Blue Nile Crossing.”

Though a neutral American, Stevens did as he was told.

“I gave the handle of the field telephone a vigorous yank, lifted the receiver and yelled Pronto…. After I had repeated the call several times an answering Pronto came from the other end. It was the Italian Army switchboard operator…. I then delivered Wingate’s spurious message. ‘What shall we do?’ shrieked the operator. I answered, ‘Clear out as quick as you can…’ A few hours later Wingate dispatched 700 Ethiopians to take the once strongly held post of the Blue Nile Crossing.”

“Not So Much a War as a Well organized Miracle”

Wingate took an even more audacious gamble after he negotiated the local Italian commander’s surrender by messenger. “Wingate himself confessed that when the moment came to receive the vanquished army he felt more alarm than at any time during the battle,” William Allen later recalled. “Across a level plain sloping to a hidden valley, the Italian commander and his staff of thirty officers advanced on horseback. Behind them came a battalion of 800 Blackshirts, and then column after column of colonial troops—many of whom were known to be reluctant to surrender. To receive this beaten army stood 36 Sudanese; these were formed up to make five lanes through which the enemy troops poured, laying down their arms in heaps; they then reformed into units and passed down into the valley where they expected to find the army which had beaten them. Instead they passed only small groups of Patriots and, standing grimly by, Wingate, lean and glaring in a shapeless wet toupee. But their arms already lay piled—covered by the Sudanis’ Brens.”

The same day Debra Markos fell, April 4, 1941, the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa fell after what the official British history of the campaign called “not so much a war as a well organized miracle.”

Six weeks earlier, the King’s African Rifles, South Africans, Nigerians, and Gold Coast troops under the command of General Alan Cunningham, as hard driving as Platt but considerably more affable, had invaded Italian Somaliland from Kenya. Intending only to capture the port of Kismayu, Cunningham, to his surprise, found himself overrunning the whole colony in just two weeks. The only resistance had been for three days at the village of Jumbo, on the far bank of the Juba River. There, the Italians fired 3,000 shells at the South Africans in three hours, forcing them to ford the river 10 miles upstream at waist level, then flank and drive the Italians out.

Fleeing Italian officers had weapons tossed from trucks to make room for their luggage. Some soldiers changed to civilian clothes, but as a South African soldier noted, “White stripes from ear to ear revealed where their chin straps had been. We left them alone.” In their stampede, the Italians had left behind a guide to every airfield and landing strip they had in East Africa; in a month the South African Air Force destroyed what aircraft had not already fallen into disrepair on the ground.

Cunningham secured permission from Middle East headquarters in Cairo to swing north into Ethiopia, and his vehicles were racing across the Ogaden Desert at 60 miles per hour toward the central Ethiopian highlands. In the meantime, British forces from Aden landed in British Somaliland to find the Italians had also fled from there.

In their only resistance, the Italians fought the Nigerians for a day at the Marda Pass and three days at the Babile Pass before withdrawing. Knowing Cunningham’s low opinion of African troops, the Nigerians’ British brigadier made a point of writing him: “It had been said that he [the Nigerian soldier] could not go short of water; he has done so without a murmur. It had been said he could not fight well out of his native bush; at Marda Pass he fought his way up mountain sides which would be recognized as such even on the Frontier. It has been said he would not stand up well to shelling and machine-gun fire in the open; at Babile, under such fire, men were trying to cut down enemy wire with their machetes. It has been said that he would be adversely affected by high altitudes and cold: at Bisidimo, after a freezing night on the hill, he advanced over the open plain at dawn with the same quiet, cheerful determination he seems always to carry about with him. He is magnificent.”

Haile Selassie’s Golden Proclamation

As the Italians fled, their colonial troops began deserting and even turning on them. “The lives of the officers were in danger every night,” one wrote. The Italian police chief in one town, besieged by rioting mutineers, telephoned the South Africans begging them to save him.

The Duke of Aosta abandoned Addis Ababa to flee northward. Cunningham’s forces entered the city the next day; the unplanned, whirlwind campaign had cost 135 killed, 310 wounded, and 52 missing while taking 50,000 Italian prisoners.

A bitter Fascist official told correspondent Alan Moorehead, “We knew the end was coming … when they stopped saying we were invincible and started printing things like this: ‘Consider as light the burdens you are enduring and the bigger burdens you must expect to endure tomorrow.’”

After some wrangling between Cunningham and Wingate, Haile Selassie entered the capital a month later. Over 50 Italian settlers had been murdered by vengeful Ethiopians before the emperor could issue what became known as the Golden Proclamation forgiving and protecting them.

Last Stand of the Duke of Aosta

The Duke of Aosta made his final stand at Amba Alagi, an 11,305-foot mountain stronghold on the Eritrean border. South African and Indian troops soon captured the surrounding lower peaks, turning the Duke’s fortress into his prison.

The duke wrote grimly in his diary: “Constant firing all day long. We spend the day jumping from one rock to another, belly to the ground, with grenade splinters coming from all sides and volleys from the machine guns that hit the rocks behind us, splattering us with pieces of stone. We are covered with dust and dirt from the explosions. Every three minutes, a plane dives on us, shooting with its front machine gun, then drops stick bombs and finally gives us another firing from the rear gun. I wish this diary had a sound track.”

Mussolini had ordered the duke to “resist to the last limits of human endurance,” but with medical services collapsing, ammunition low, and, perhaps worse for the Italians, their chianti supply blown up, he authorized capitulation.

The duke and 5,000 men surrendered on May 29, 1941. Italians isolated by the rainy season would hold out in other parts of Ethiopia for six months, but the Italian empire in East Africa was dead. Its demise was little noted. In Britain attention was fixed on the Blitz, the Middle East, and Greece. In Italy, Fascist press censorship kept it unreported, Ciano left it unremarked upon in his diary, and Mussolini dismissed it as “hav[ing] no effect on the outcome of the war.”

Two of those involved in the empire’s demise did not long outlive it. The Duke of Aosta, POW No. 1190, died the next year in Kenya of tuberculosis, Wingate two years after in a plane crash in Burma while directing his still controversial Chindit campaign.

The luck that carried American Legionnaire John Hasey unscathed through the assault on Massawa deserted him two months later in Syria. While in action against, ironically, Foreign Legionnaires loyal to Vichy, he was so critically wounded he was discharged and saw no further service in World War II while his Foreign Legion unit would go on to be decimated in North Africa, Italy, and Alsace-Lorraine.

The subordinate general, William Slim, went from East Africa to greater glory as he led the 14th Army to victory in Burma and became a field marshal while the commanding generals finished the war in obscurity. William Platt became commander in chief, East Africa, for what little that was now worth. Sent to command the Eighth Army in the Middle East with no experience whatever in armored warfare, Alan Cunningham was so crushed by Rommel that he spent the rest of the war in regional commands in Britain.

Emperor Haile Selassie avoided being overthrown in a 1960 coup attempt, but was deposed by Marxist officers in 1974. He died a year later in captivity, likely murdered.

A quite astoundingly magnificent appraisal of the East African campaign the like of which I have never come across in any present or past WW2 historian claimants. Indeed and too often much to the contrary there has been what appears if not a complete and utterly shameful ignorance of the region a wanton deliberation to steer anyone interested away from this first long-standing successful land confrontation with the Axis forces and their satellite potential collaborateurs that were the Vichyite governors of Djibouti, Syria and Madagascar, General Dentz in particular. Even dear Winston got it wrong when with natural uplifting pride he announced that El Alemein was our first victory, disappointingly ignoring that it was Keren. A pity there doesn’t seem to be much filmed news reporting of the events covered in your brilliant article account.