By David Alan Johnson

November 13, 1942, was a Friday, which sailors aboard the cruiser USS San Francisco noted with anxiety. The ship had already had some bad luck the day before, when 16 torpedo-carrying Japanese Mitsubishi Betty bombers attacked the cruisers and destroyers of Task Group 67.4. Eleven of the Bettys had been shot down, and none of the ships had been hit by torpedoes.

One of the damaged bombers, however, had crashed into San Francisco’s after fire control station, killing one officer and 23 men. None of the other ships suffered any damage. The sailors hoped that the freak accident had cured the ship from any further bad luck, even though it was Friday the 13th.

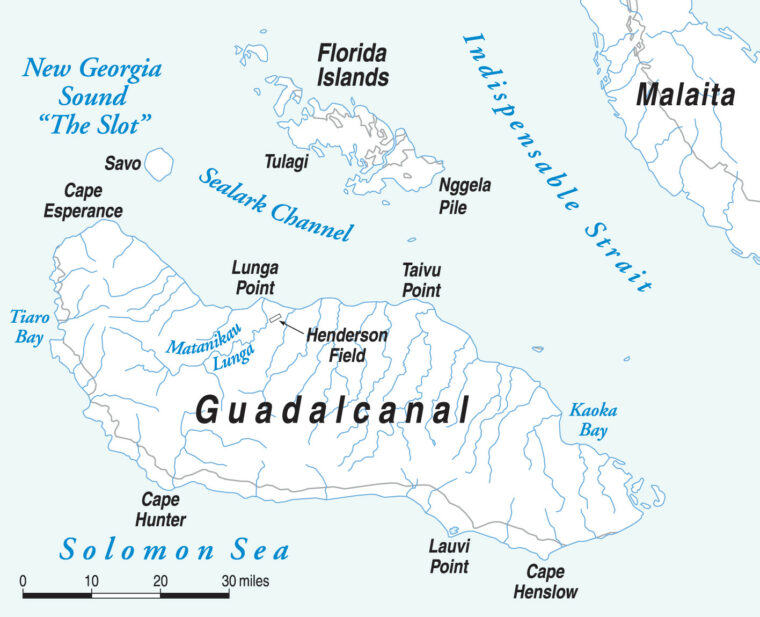

The task group would be needing all the good luck it could get. That afternoon, an American reconnaissance aircraft had discovered a Japanese naval force under Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe sailing southeast at 25 knots through the Solomon Islands down New Georgia Sound, nicknamed “the Slot,” toward Guadalcanal. Abe’s force consisted of two battleships, his flagship Hiei and Kirishima, along with one cruiser and 14 destroyers. Admiral Richmond K. Turner, commander of the American amphibious landings on Guadalcanal, rightly surmised that the Japanese fleet was coming south either to attack his transports as they withdrew from Guadalcanal or to bombard Henderson Field, which was vital to the American defense of the island.

Abe’s bombardment force was only half of the Japanese attack on Guadalcanal. Following the bombardment of Henderson field, 11 transports were scheduled to land 7,000 troops on the island. Six of the transports were to unload their men at Cape Esperance, the other five at Tassafaronga. With no air cover from Henderson, the U.S. Marines would either be killed or taken prisoner. But first, the American airfield would have to be destroyed by Abe’s battleships.

The “Iron Bottom Sound”

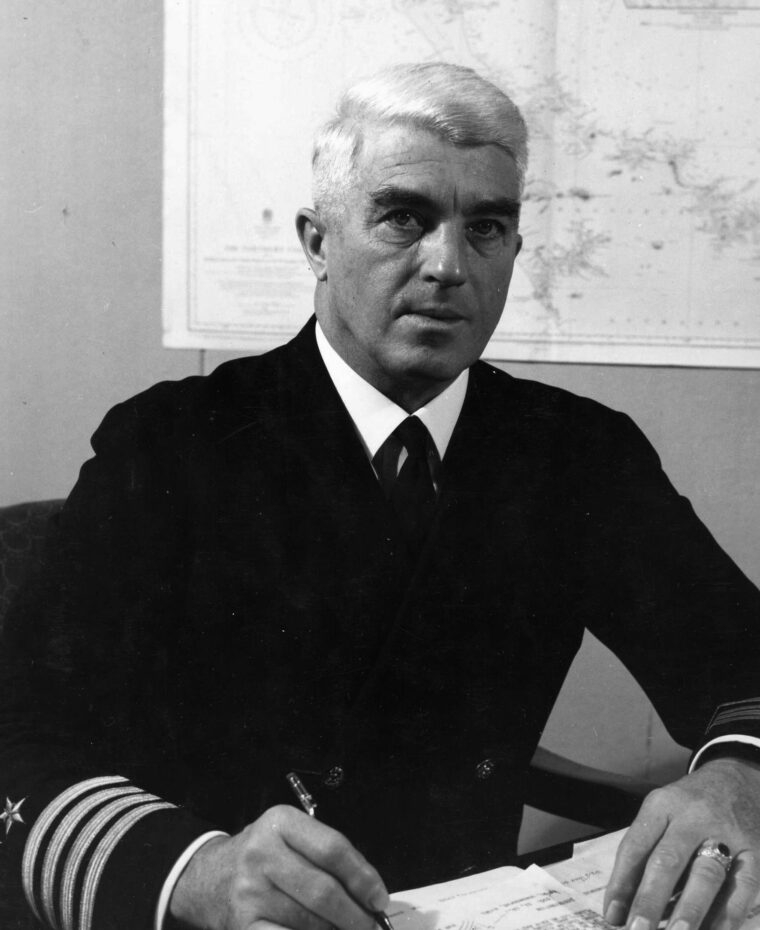

The initial American landings on Guadalcanal had taken place in August 1942, and were the first large-scale offensive land operation initiated by the United States against the Japanese in World War II. Sent to confront Abe in the waters off the embattled island was a U.S. Navy force of five cruisers and eight destroyers commanded by Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, who flew his flag aboard San Francisco.

Callaghan’s task group was heavily outgunned, but Admiral William F. Halsey’s Task Force 64 was too far to the south to offer any assistance. In his definitive account of the fighting in and around Guadalcanal, historian Richard B. Frank pointed out that each American cruiser could fire a broadside of 8-inch shells weighing 2,340 pounds, while each Japanese battleship’s broadside of 14-inch shells totalled 11,920 pounds. It was hoped that Callaghan’s torpedoes might tip the balance, but even here the American force fell short. Not only did the Japanese ships carry more torpedoes, but their Long Lances were fast and deadly, while the American Mark 14 torpedoes were inaccurate and unreliable, sometimes failing to explode even when they did hit their targets.

For more than three months, since August, Japanese air, land, and naval forces had been trying to push American troops off Guadalcanal and put Henderson Field permanently out of operation. The first strike came on August 7, when Japanese bombers attacked the transports, just hours after the 1st Marine Division had gone ashore. Allied and Japanese warships came into contact on the night of August 8 in what became known as the Battle of Savo Island. Four cruisers, three American and one Australian, were sunk in that action, while the Japanese force suffered no losses.

During the Battle of Cape Esperance, on the night of October 11, American cruisers and destroyers commanded by Admiral Norman Scott caught a Japanese force north of Guadalcanal and executed the classic crossing of the enemy’s T, steaming across the bows of the Japanese to deliver broadsides. Scott’s force sank one Japanese cruiser and one destroyer, while losing a destroyer in the battle. Two nights later, a Japanese bombardment force led by battleships Kongo and Haruna shelled Henderson Field for an hour and a half. An American writer said that the airfield “had been blasted almost beyond recognition.”

Most of the naval action that swirled around Guadalcanal took place in the Sealark Channel, a stretch of water between Guadalcanal, Savo Island, and Florida Island. So many ships went down in this narrow channel that it had been rechristened “Iron Bottom Sound.” More than 40 ships, Japanese, American, and Australian, would be sunk within its confines before the Guadalcanal campaign ended. Tonight’s Japanese effort would be the latest and one of the most brutal attempts to shell the Marines on the island into submission.

Uncle Dan’s 15 Days of Seniority

The American transports anchored off Guadalcanal were ordered to leave the area, even though only about one-third of their cargo, including ammunition, some much-needed artillery, and 6,000 troops, had been unloaded. Callaghan’s task group escorted them away from Guadalcanal on the first leg of their journey back to Noumea. Once they were on the open sea and on their way, Callaghan reversed course and headed back toward Guadalcanal.

The American cruisers and destroyers formed a single column as they entered Lengo Channel. Five of Callaghan’s ships, the destroyers O’Bannon and Fletcher, the light cruisers Helena and Juneau, and the heavy cruiser Portland, were equipped with the new SG search radar, which Callaghan hoped would prove its worth on this overcast night. Callaghan has been criticized for not placing his radar-equipped ships at the head of the column. O’Bannon was closest to the front of the line, and she was number four in the formation.

Admiral Callaghan was certainly well liked by just about everyone—his men called him “Uncle Dan”—but Rear Admiral Norman Scott, a classmate of Callaghan’s at the U.S. Naval Academy, was also part of the task group, sailing aboard the cruiser Atlanta. Admiral Scott had more combat experience than Callaghan and had successfully countered a Japanese force in the night surface action at Cape Esperance. Apparently, Callaghan had been chosen as a flag officer because he had 15 days of seniority over Scott.

Avoiding Collisions in the Dead of Night

However, this complicated situation was forgotten during the early hours of November 13. As Helena passed Lunga Point at 1:24 am, her SG radar first made contact with the Japanese fleet: “Contact bearing 312 and 310 [degrees], distant 27,000 and 32,000 yards.” The two contacts were the destroyers Yudachi and Harusame, which were just over 10 miles from the destroyer Cushing at the head of the American column. Callaghan ordered the column to turn right to 00 degrees—due north—intending to cross the T with the approaching Japanese force. By the time the column had begun making its turn, the radar blips had become distinctive groups, two battleships, along with the smaller shapes of screening destroyers and cruisers.

Callaghan had not ordered a sharp enough turn to starboard—instead of crossing in front of the Japanese formation, he nearly collided with it. At 1:42 am, Commander Thomas M. Stokes aboard Cushing reported three enemy destroyers passing in front from port to starboard. Actually, there were only two destroyers, Yudachi and Harusame. The two Japanese destroyers also saw Cushing.

Admiral Abe was taken completely by surprise. None of his ships had radar, and the last thing he expected was a night surface action. Also, ground observers on Guadalcanal radioed that they could see no sign of enemy ships. Abe had already ordered the thin-skinned Type 3 shells—the kind of shell used to bombard enemy ground positions—loaded into the breeches of the two battleships. At 1:30 am, he had given the order, “Gun battle. Target airfield.”

Yudachi’s report that enemy ships had been sighted changed everything. Aboard the battleships Hiei and Kirishima, gun crews began changing ammunition from bombardment shells to armor-piercing rounds. At 1:45, Abe ordered his captains to shift targets to enemy ships.

Cushing turned to port to bring her torpedo tubes to bear. Over the intership radio, appropriately called TBS for “talk between ships,” Commander Stokes asked, “Shall I let them have a couple of fish?” Callaghan gave permission to launch torpedoes. At 1:45 am, Stokes ordered, “Stand by to open fire,” and minutes later ordered a return to course 00. The quick changes from west then back to due north threw the neat column into confusion. The three destroyers astern of Cushing—Laffey, Sterett, and O’Bannon—also turned to port. Atlanta, just behind the destroyers, had to swing sharply to port to avoid collision. San Francisco had to turn to avoid hitting Atlanta. “What are you doing?” Callaghan asked over the TBS. “Avoiding our own destroyers,” replied Atlanta’s captain.

“Commence Firing! Counter-Illuminate.”

Atlanta’s high superstructure made her much more visible than the smaller destroyers. At 1:50, Japanese searchlight shutters clicked open and lit up Atlanta’s port side. The cruiser’s gunnery officer shouted, “Commence firing! Counter-illuminate.” The ship’s 5-inch guns shot out one of the three offending lights and scored several hits on an enemy destroyer, possibly Akatsuki. But the Japanese ships, now on both bows, concentrated their fire on Atlanta, which was the brightest object in sight. One shell hit the bridge and killed Admiral Scott and all but one of his staff. One Long Lance torpedo and possibly a second also hit the ship. Atlanta slowed to a stop, dead in the water, and mortally wounded only minutes after the battle had started. Admiral Callaghan ordered, “Odd ships commence firing to starboard, even ships to port.”

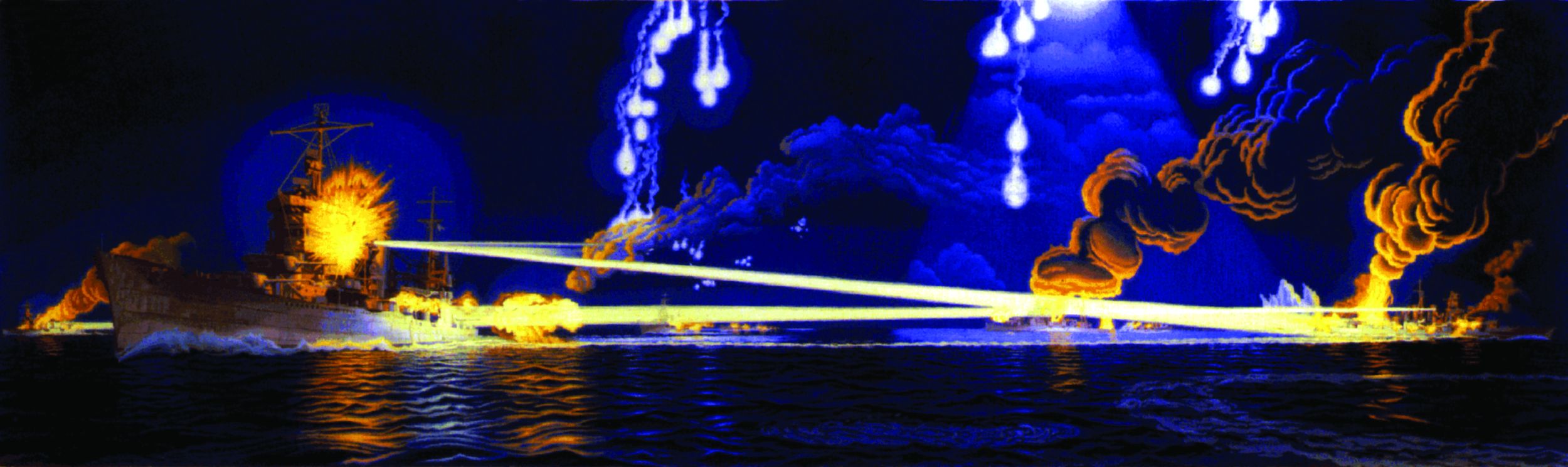

At this point, “Japanese and American ships mingled like minnows in a bucket,” according to naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison. Existing records offer some idea of the confusion that took place in Iron Bottom Sound that night, but giving a conclusive, blow-by-blow description of the fighting is all but impossible. One of the participants said that the fight was like “a barroom brawl after the lights had been shot out.”

Leading destroyer Cushing opened fire on an enemy destroyer 2,000 yards to starboard, while her 20mm gunners fired at the battleship Hiei. Cushing was hit several times, all power lines were cut, and speed was sharply reduced. Even in her disabled condition, the destroyer fired six torpedoes at Hiei, none of which exploded. A searchlight beam located Cushing, and gunfire from both sides reduced her to a sinking wreck. With no power to move or to fight the fires that were spreading throughout the destroyer’s length, Cushing was abandoned.

Next in line, the destroyer Laffey also launched torpedoes at Hiei. These were fired at point-blank range and did not have time to arm before striking the battleship. Following this encounter, Laffey came in contact with three Japanese destroyers that hit her with gunfire several times and blew her stern off with a torpedo. A large-caliber salvo from the battleship Kirishima, which had managed to avoid contact with American ships so far, completed Laffey’s destruction. The crew abandoned ship as the destroyer was sinking, but the burning hull exploded while a number of them were still in the water. Many men were killed, including the destroyer’s captain.

Following in the original line ahead of the formation were the destroyers Sterett and O’Bannon. Sterett was hit by a salvo while she was taking an enemy ship under rapid fire. The shells destroyed her radar and her aft 5-inch guns and disabled her steering gear. The captain, Lt. Cmdr. Jesse Coward, managed to maneuver the ship by use of her engines and also fired four torpedoes at Hiei along with several 5-inch rounds. Once again, the torpedoes either missed or failed to explode. With his ship on fire and half of his main battery out of action, Coward then took Sterett out of action, nearly colliding with O’Bannon.

All of Hiei’s batteries opened fire on O’Bannon, but the battleship’s guns could not depress far enough and all of the shells passed overhead. O’Bannon returned the compliment, opening fire with her 5-inch batteries as well as launching two torpedoes at the battleship. Hiei was the largest and slowest target of opportunity and had been hit by a hail of medium- and light-caliber shells. As O’Bannon broke off action, her crew could see fires all over the enemy ship.

“Cease Firing Own Ships”

Admiral Abe not only had been thoroughly alarmed by the American attack but was also taken aback by the intensity of it. The Americans had penetrated his screen of destroyers and attacked his battleships, which were the center as well as the main components of the bombardment group. He had no real idea of what had happened so far during the battle or that his force had sunk two enemy destroyers and had knocked one cruiser out of the fighting. From his position on Hiei’s bridge, all that Abe really knew was that his flagship had been damaged and set afire, sometimes by destroyers firing at what amounted to point-blank range. An American writer said that the distance was “rifle-shot range.”

Admiral Abe’s alarm over Hiei’s condition was justified. The battleship’s forward pagoda mast had been hit and set on fire in several places. Eighty-five 8-inch and 5-inch shells had destroyed all of the ship’s light antiaircraft guns and all radio and signal equipment, and had severed all control circuits for the main battery. The secondary battery’s directors were also put out of action. At one point, Hiei’s 6-inch guns opened fire on the Japanese destroyers Asagumo, Murosame, and Samidare. At about 1:55 am, an 8-inch shell from San Francisco jammed her rudders and flooded her steering gear. San Francisco broke off with Hiei and began firing at two destroyers on her starboard bow, probably Yudachi and Harusame. After hitting the first target and setting it on fire, Captain Cassin Young ordered gunnery to shift to the second destroyer. In the confusion that followed, it seems likely that the disabled Atlanta drifted into San Francisco’s line of fire. Two full salvos from San Francisco hit Atlanta’s superstructure. Some accounts claim that Admiral Scott was killed during this encounter, not in the earlier action against the Japanese.

As soon as Admiral Callaghan realized what had happened, he broadcast, “Cease firing own ships.” Some ships stopped firing. Others either ignored the order or did not hear it. Captain Lawrence Dubose of the cruiser Portland asked, “What’s the dope, did you want us to cease fire?” Callaghan replied, “Affirmative.” Callaghan quickly reversed the order, though, and broadcast, “Give her hell!” and “We want the big ones! Get the big ones first!” Unfortunately for San Francisco and her crew, the hell came from the other side. Both Hiei and the cruiser Nagara opened fire on the American cruiser. Hiei’s third salvo of 14-inch shells hit San Francisco’s bridge, blowing the navigator over a bulwark and onto a 5-inch gun mount. The gun crew thought he was dead; they picked him up and threw him onto a pile of spent shell casings. The battleship’s 6-inch guns also hit San Francisco several times. One of these shells wounded Captain Young, who later died as a result of his injuries. Another hit a steel girder directly above Admiral Callaghan, killing him instantly along with all but one of his staff.

A Combat Life of Seven Minutes

During the fighting, San Francisco’s bow had swung around to the south. Commander Bruce McCandless and a quartermaster were the only people alive on the bridge. McCandless ordered a turn to the west, back toward the enemy. But the bridge itself was filled with bodies and parts of bodies along with the jagged remnants of gear and equipment. The ship had been holed 45 times, was taking water, and had several guns knocked out of action, and damage control reported 25 fires on board. With the remaining guns, crews continued firing at both Hiei and Kirishima as well as an enemy destroyer that passed along the cruiser’s port side. McCandless took stock of San Francisco’s situation and reversed course, heading back east along Guadalcanal’s northern coast. In spite of the superstitions about Friday the 13th, the ship was a lot luckier than many other members of the task group. She was still afloat and heading out of the area under her own power.

A Japanese torpedo hit Portland near the stern on the starboard side, blowing off her starboard screws and bending the hull plates so badly that the cruiser could only turn in circles to the right. As the ship turned involuntarily, her guns came to bear on the unfortunate Hiei. Portland’s gunners fired four salvoes from her forward turrets and claimed 10 to 14 hits. Captain Dubose did not want to risk firing at any other ships in the darkness. With ships milling about and mingling with each other, it was impossible to tell friend from foe.

Juneau was the last cruiser in the column, just astern of Helena. She was hit by a torpedo before she had much of a chance to take part in the fighting. The hit disabled her steering and may have broken her keel. She fired very few rounds, possibly as few as 25. Her captain took her out of the battle, hoping to find a place to make repairs, and nearly collided with Helena. Helena, meanwhile, was having a fairly lucky time of it. Her main batteries and secondary guns had damaged at least two enemy destroyers, and her 40mm guns blazed away at the cruiser Nagara. Helena was hit five times but suffered only minor damage. One of the hits stopped her bridge clock at 1:48 am.

The destroyer Barton was having a rough time. Barton had been one of the four destroyers at the rear of the column before it scattered. Her 5-inch batteries fired at enemy searchlights, and she fired five torpedoes, although there is no indication that any of them hit their targets. At about 2 am, her captain stopped to avoid collision with another ship. A stationary target, she was hit by two torpedoes almost immediately, broke in two, and quickly sank. Only the men who were topside had any chance of escaping. Over 60 percent of her crew were lost. Barton had been commissioned on May, 29, 1942, less than six months earlier, and had a combat life of exactly seven minutes.

The destroyer Aaron Ward had been ahead of Barton and was having a difficult time keeping friendly ships and enemy ships separated. Her gunners began firing at the brightly illuminated Hiei, but had to cease after only 10 salvoes when friendly cruisers entered her line of fire. A few minutes later, her captain was forced to reverse engines to avoid collision with a ship ahead—either Helena or Yudachi. Two torpedoes then passed directly under the ship. These may have hit Barton, which blew up and sank close on Aaron Ward’s starboard side.

In less than half an hour, Aaron Ward had damaged at least two enemy vessels, including the already battered Hiei, but had not escaped damage herself. During all the frenzy, confusion, and frustration that characterized the night action, the destroyer had taken nine direct hits, three of these from 14-inch shells. In about 30 minutes, the fire director, radar, and steering control had all been disabled. At about 2:35 am, the hits finally took their toll and all power failed. Aaron Ward began drifting with the current.

“The Star Shells Rose, Terrible and Red”

The battle was taking place just off the north coast of Guadalcanal. The gun flashes and resulting fires and explosions were plainly visible to the Marines on the island. Robert Leckie, a Marine private, gave this impression of the fighting: “The star shells rose, terrible and red,” he wrote. “Giant tracers flashed across the night in orange arcs … the sea seemed a sheet of polished obsidian on which warships seemed to have been dropped and were immobilized, centered amid concentric circles like shock waves that form around a stone dropped in mud.”

The Marines knew that their existence depended upon the outcome of the fighting that was taking place right in front of them, but they also realized there was nothing they could do but watch. They could not have known it, but at about 2 am Admiral Abe ordered Hiei and Kirishima to turn north and steam away from Guadalcanal. The bombardment of Henderson Field had been cancelled. Abe’s bombardment group had been shot up by an enemy column he did not even know was in the area. He did not want to expose his ships to any further damage. Kirishima executed the turn smartly and began making her way north of Savo Island. She had been hit only once, by a 5-inch shell. But Hiei could barely turn at all and quickly lagged behind.

While Abe’s flagship limped northward behind Kirishima, the fighting went on. The destroyer USS Monssen launched five torpedoes at Hiei at about the time Abe ordered a withdrawal from the area. None hit their targets. A destroyer then emerged from the darkness on Monssen’s port side, her 5-inch gunners fired at the ship, and the torpedo officer launched her remaining torpedoes. Again, there is no record that any of the torpedoes hit.

Monssen’s 20mm gunners opened up at another destroyer when a starshell burst overhead “lighting up the ship like a nightclub floor show.” The captain thought the shells were friendly and switched on Monssen’s recognition lights. At least two enemy searchlights immediately converged on the ship, followed by a torrent of enemy shells. Thirty-seven of them hit the destroyer, reducing it to a burning hulk.

The very last ship in the line was the destroyer Fletcher—number 13 in formation. Her crew watched Barton blow up and saw Monssen pummeled by gunfire, while her own gunners fired at two enemy ships and had the satisfaction of seeing fires break out on the second target.

Heavy Casualties on Both Sides

Because of the melee of ships in the area, the decision was made to withdraw to the east and get a clearer picture of the situation. With the help of her radar, Fletcher picked her way back through the ships, friend and foe, that dotted Iron Bottom Sound. She fired five torpedoes at a large vessel that might have been the cruiser Helena. All missed. After firing her remaining torpedoes at other targets, Fletcher’s captain once again retired eastward, this time out of the battle. Although she had been in the area for as long as the other American destroyers, Fletcher had not been hit by enemy gunfire and suffered no damage.

Aboard Helena, Captain Gilbert C. Hoover ceased firing at 2:16 am. The enemy had withdrawn from the area, and nine ships were burning in Iron Bottom Sound. Captain Hoover tried to contact both Callaghan and Scott. Receiving no reply and believing himself to be the senior surviving commander, Hoover ordered all ships to retire. It had been just 41 minutes since the battle was joined.

During the fighting southeast of Savo Island, two American destroyers, Barton and Laffey, had been sunk. One Japanese destroyer, Akatsuki, had also gone down, and Yudachi was on fire and would soon join her. At 3 am, Kirishima sent a report describing the night action. The communiqué reported the fighting as a “severe mixed battle,” and went on to say that both sides suffered “considerable damage.” Landings of Japanese troops on Guadalcanal that had been scheduled for that night were postponed. The transports reversed course and steamed back to base.

With the morning, Marines on Guadalcanal could see the remnants of the battle they had witnessed the night before. Severely damaged American and Japanese warships, crippled or dead in the water, littered the surface of Iron Bottom Sound. They could not see Hiei, which was hidden behind Savo Island. Atlanta, however, was still on fire and drifting; Aaron Ward was also drifting, struggling to get under way under her own power; Portland steamed in circles, her hull bent; and Cushing and Monssen burned from fires within their hulls and superstructures. Yudachi was also still on fire. The tug USS Bobolink came chugging out of Tulagi harbor to assist in salvaging the crippled American ships as well as to rescue survivors. Hundreds of American sailors dotted the surface of the water north of Guadalcanal.

Support from the Air

The ships might have been badly shot up, but they still had their share of fight. Even though Portland could not steer a straight course, her guns still worked. As she made one of her endless circles, her main battery came to bear on Yudachi, 12,500 yards to the northwest. Her sixth salvo hit the destroyer’s after magazine, and Yudachi blew up and sank. It was a welcome sight to the American survivors in the water and to the Marines on Guadalcanal.

Hiei’s gunners returned the compliment. At about 6:30 am, the battleship’s after turrets blasted away at Aaron Ward, 13 miles to the southeast. The destroyer managed to get under way, but her power failed again less than 20 minutes later. Hiei’s third salvo straddled the destroyer but did not score any hits. Fortunately for Aaron Ward, Marine aircraft from Henderson Field made their first appearance of the day, and the Japanese gunners forgot all about Aaron Ward. Bobolink was on hand to tow her out of range to the safety of Tulagi harbor.

The American dive-bombers and torpedo bombers of Henderson Field now turned the tables on Hiei. Five Douglas Dauntless dive- bombers and four Grumman Avenger torpedo planes attacked the stricken Hiei, claiming one bomb and one torpedo hit. Throughout the morning, the Dauntlesses and Avengers continued to hurl themselves at the crippled battleship, which maintained an erratic course to the northwest. At 8:15 am, Admiral Abe left his flagship and transferred to the destroyer Yukikaze.

The air attacks continued, including sorties by Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bombers. Hiei’s captain, Masao Nishida, acknowledged three bomb hits and at least four torpedo hits. Admiral Abe sent a communiqué to Captain Nishida, ordering him to run Hiei aground on Guadalcanal, but Nishida either did not receive the order or ignored it. He may not have been able to carry it out anyway because the tough old battleship probably could not steam the 14 or so miles to Guadalcanal. By mid-afternoon, Hiei had begun listing from torpedo damage. Abe decided that the ship could not be saved. He ordered the battleship scuttled.

While the assembled crew shouted three banzais and the naval ensign was lowered, the Kingston valves were opened. Torpedo planes scored two more hits before the crew, along with the emperor’s portrait, could be removed. In spite of all this, Hiei did not go quietly, staying afloat until nightfall.

Assessing and Accruing Damage

Hiei was not the only ship to be scuttled that Friday. The crew of Atlanta did its best to salvage the ship, manning the pumps, lightening the ship by throwing gear and equipment over the side, and even by forming a bucket brigade. Bobolink appeared on the scene after taking Aaron Ward to Tulagi, but there was little that the tug could do—49 shell hits and one torpedo had taken their toll. The foremast had toppled, seven of the eight 5-inch turrets had been hit, and the guns drooped uselessly onto the decks. Fires still blazed in the superstructure. By 2 pm, the cruiser was at anchor off Kukum, where she had been towed by Bobolink, but it was evident that she could not be kept afloat. She was listing 10 degrees to port, and water continued to flood her hull. Admiral Halsey ordered the crew to be removed, and demolition charges were set. The charges did their work, and Atlanta went down at 8:15 pm, three miles west of Lunga Point.

Aboard Portland the situation was not nearly as bad, although Captain Dubose was not having an easy time regaining steering control. He tried steering with the engines and by using sea anchors without any success. The bent stern continued to turn the ship in a circle. While these maneuvers were being tried, her crew watched as the burning hulks of the destroyers Cushing and Monssen sank below the surface of Iron Bottom Sound’s oil-covered waters. Finally, Bobolink intervened, pushing against Portland’s starboard bow relentlessly and allowing the ship to strain ahead on a steady course. Portland finally arrived within the friendly confines of Tulagi harbor at 1 am on November 14.

The American ships that had been able to withdraw from the night action took part in a sort of postscript to the battle. Only six ships, commanded by Captain Hoover aboard Helena, were seaworthy enough to leave Iron Bottom Sound under their own power. Besides Helena, the cruisers San Francisco and Juneau, escorted by the destroyers O’Bannon, Sterett, and Fletcher, set a southeasterly course toward the American base at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides. The formation zigzagged but was limited to 18 knots because of the torpedo damaged Juneau.

In spite of the destroyer screen, the Japanese submarine I-26 was able to get into firing position and launch a spread of torpedoes at San Francisco. All the torpedoes missed their targets, but one hit Juneau. Sailors aboard San Francisco watched as the cruiser exploded. “She didn’t sink,” Commander McCandless later wrote. “She blew up with all the fury of an exploding volcano. When the smoke of the explosion cleared, no trace remained except oil and debris.” Helena’s action report simply stated, “Juneau torpedoed and disappeared lat. 10″ 32′ S, long. 161″ 2′ E at 1109.” Among those killed were the five brothers of the Sullivan family of Waterloo, Iowa. Because of this disaster, the U.S. Navy prohibited two or more family members from serving aboard the same ship ever again.

A Costly but Important Victory

“So ended the wildest, most desperate sea fight since Jutland,” pronounced Samuel Eliot Morison about the surface engagement of Friday the 13th. The Americans lost more ships and more men than the Japanese—two American cruisers, four destroyers, and 1,439 men (including 683 aboard Juneau), as opposed to two destroyers and the battleship Hiei and 552 dead and missing on the Japanese side. But Admiral Abe’s bombardment of Henderson Field had been stopped, and the Marine air units on Guadalcanal were still as alive and as aggressive as ever. In other words, it had been a tactical victory for Japan but a strategic reversal.

In retribution for the failure to carry out his assigned mission, Admiral Abe was relieved of his command. Abe did his best to give a positive impression of his accomplishments, reporting that his bombardment group had sunk five heavy cruisers, two Atlanta-class light cruisers, six destroyers, and one torpedo boat in spite of the fact that he had been taken by surprise. His own losses were accurately given as Hiei, along with destroyers Yudachi and Akatsuki, although he went on to say that other ships in his group suffered only slight damage. This was not the case, though. The destroyer Ikazuchi was put out of action by shell fire and was much more heavily damaged than Abe admitted, while the captain of Amatsukaze described his ship as a “floating wreck.”

The loss of a battleship was a serious setback to the Japanese, who were all too aware of the fact that they could not replace ships and matériel as readily as the Americans. The chief of the Naval General Staff, Admiral Osami Nagano, told another admiral, “The Japanese navy is different from the American navy. If you lose one ship it will take years to replace.” Admiral Abe was ordered to the Naval General Staff on December 21, a face-saving job, and he retired the following March at the young age of 53. Captain Nishida of Hiei also retired soon after the loss of his ship.

Admirals Callaghan and Scott did not live to see Abe withdraw from the battle. But the American force had won the day in spite of its losses. Both admirals were awarded the Medal of Honor for their part in the battle, and both also had warships named after them.

When the Japanese abandoned Guadalcanal to the Americans in February 1943, it was a turning point in the Pacific War—and it was due in part to the heroism of the men of the U.S. Navy.

David Alan Johnson is the author of the book The City Ablaze, which is an hour-by-hour eyewitness account of the December 29, 1940, fire blitz on London. He resides in Union, New Jersey.

Read “Neptune’s Inferno”for a much better account of the engagement and all the others around the “Canal”.