By John J. Domagalski

The first days of January 1943 found American forces winning the prolonged struggle for control of Guadalcanal in the South Pacific. The Imperial Japanese Navy had been defeated in a decisive naval battle the previous November. Fresh American troops were pushing the Japanese into a shrinking perimeter on the western side of the island. The Japanese supply line slowed to a trickle due to growing American air and sea power.

Even as the Japanese were slowly losing the fight for Guadalcanal, work was under way to strengthen their positions farther north in the Central Solomons, a region that had been largely bypassed in 1942 by Imperial forces in favor of Guadalcanal. It now took on a new level of importance because of their unfavorable results in the south.

Never able to dislodge control of the airfield on Guadalcanal from the stubborn American defenders, the Japanese sought an alternate location to build a new one from scratch. Positioned about 175 miles northwest of Guadalcanal, New Georgia Island was determined to be an ideal place. The location would shorten the flight time for aircraft now flying to Guadalcanal from bases farther north.

In late November 1942, a small Japanese convoy landed on the southwestern portion of New Georgia. Work began immediately near Munda Point to build a runway at a small coconut plantation. Flanked by the smaller Rendova Island, the area was largely sheltered from seaborne invasion because of its shallow water and dangerous reefs.

This increase in Japanese activity around New Georgia was immediately noticed by American eyes. Aerial reconnaissance, however, initially did not detect the airfield because clever Japanese workers had strung cables along the top of coconut trees before cutting down the trunks as part of the runway construction. As a result of the ruse, the airfield escaped American detection until early December when it was almost 90 percent complete.

Once aware of it, Allied planes immediately began to bomb and strafe Munda on a regular basis in an attempt to prevent the completion of the runway. Japanese workers, however, simply repaired the damage and continued with the construction. In spite of the continuous air attacks of ever-increasing intensity, the airfield was operational by Christmas.

American commanders saw the new air base as a serious threat. In addition to cutting the flight time to Guadalcanal, it could be used as a possible staging point for another Japanese counterattack.

With airpower alone unable to shut down Munda, Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, the American commander of naval forces in the South Pacific, devised an ambitious plan: He decided to bombard Munda from the sea. Venturing up the Solomons Islands chain into Japanese waters would be the first mission of its kind. The daring undertaking close to enemy air and sea bases was a risky and dangerous.

Ainsworth’s Plans For the Bombardment

Admiral Halsey tapped Rear Admiral Walden Ainsworth to lead the operation. Recently promoted to flag rank, Ainsworth had moved over to the Pacific from the Atlantic Theater where he had led a destroyer squadron; Halsey put him in charge of Task Force 67. The force had been recently rebuilt after suffering heavy damage in the Battle of Tassafaronga off Guadalcanal the previous November.

The scope of the operation expanded when Halsey decided to combine the bombardment mission with a delivery of Army reinforcements to Guadalcanal scheduled for January 4. The seven transports slated to carry the soldiers to the front lines would also pick up Marines for a return trip to Australia. With the advances American forces were making on the ground, it was imperative that the supply operation be completed without Japanese interference.

Operating in distant support of the combined mission would be three battleships and four destroyers under Rear Admiral Willis Lee. To draw attention away from the supply operation, land-based aircraft were scheduled to hit Munda and air bases farther north in the days leading up to the operation.

Immediately upon receipt of Halsey’s orders, Admiral Ainsworth grappled with a plan for the bombardment operation. He felt there were two critical issues that needed to be addressed in the planning. “First, how to get in there undetected, or at least deny the enemy any knowledge of our intended move in his direction,” Ainsworth later wrote.

“Second, how to retire beyond reach of his land-based air by daylight the following morning and make use of the air coverage provided for us. The time and duration of the bombardment depended on these two factors.”

A large-scale chart of the area and a mosaic of the latest aerial reconnaissance photos were obtained for planning purposes, and the details of the operation began to take shape. The admiral learned he had additional resources at his disposal for the operation when a dispatch disclosed that the submarine Grayback would be stationed near the bombardment area to serve as a navigational aid. The submarine was already en route to New Georgia and thus was incorporated into the overall plan.

Once the navigation details were set, planners turned their attention to the firing arrangement. It was clear the final approach to the point of fire had to be carefully planned due to the confined waters between New Georgia and Rendova. “It was also apparent that greater accuracy could be obtained by having the ships fire singly.” Noted Ainsworth. “A study of the bombardment area and the ammunition available gave us an estimate of the fire effect available, and we found we could distribute it over an hour and get a very fair bombardment.”

The admiral’s conclusion was to begin the bombardment at 1 am on January 5, 1943, and pour fire onto Munda for one hour.

Ainsworth and his staff worked feverishly to finalize the plan even as the warships put to sea. A careful review was undertaken to ensure that nothing of importance was overlooked. The planning concluded with a final conference between Ainsworth and his ship captains aboard the cruiser Louisville.

Ensuring Effective Communication

Concerns were raised during the meeting about the time spent in the confined waters off Munda during the approach and firing times. Captain Charles Cecil of the cruiser Helena was particularly uneasy about the situation as his ship would be the last of the three cruisers to fire, so the location of the bombardment force would be well known at that juncture. He made sure his gunners had antiship ammunition close at hand should the task force run into trouble.

Ainsworth foresaw the possibility of communication problems during the mission and took steps to prevent it. “The night bombardment of Munda is the first naval action against shore installations in which the most modern instruments, including our latest developments in radar, were available for navigation and fire control purposes,” he wrote. “It is also the first action in which our navy has coordinated surface, submarine, and aircraft units in a night bombardment.” Timing and communication among the various units would be of the utmost importance to the success of the operation.

After polling his cruiser commanders, the admiral concluded the Curtiss SOC seaplanes carried aboard the warships were not well suited for night bombardments and thus would not play a major role in the mission. Therefore, a number of Black Cats––Catalina PBY seaplanes specially equipped with radar for night operations––were placed at his disposal.

To help ensure good communication between the ships, planes, and submarine, one PBY was outfitted with an aircraft radio set obtained from the aircraft carrier Enterprise. Ainsworth also directed a member of his staff to make additional preparations.

“Lieutenant Commander Crowley, Aviation Officer of my staff, together with the Operations Officer [of the South Pacific Command] drew up the coordinating plan for Black Cat spotting operations,” the admiral noted. Crowley and two well-trained aviation spotters went to Guadalcanal to ride along on night flights over Munda in the days leading up to the bombardment.

Taking place on the nights of January 2 and 3, the flights were the final precursor to the bombardment operation. “The planes arrived over Munda Point at about midnight on each of these nights and harassed the airfield area with 500-lb. bombs (four each plane), 30-lb. demolition bombs, motor shells, and flares,” Crowley reported. “This harassing was extended over a period of two to two-and-a-half hours each night.”

In addition to harassing the Japanese, the two night’s worth of bombing allowed Crowley and his men to become familiar with the Munda area for the pending mission.

Sailing Through the Dark

The transports arrived safely at Guadalcanal and unloaded their occupants during the early evening hours of January 4. The completion of the reinforcement operation signaled the start of the bombardment mission, and Admiral Ainsworth departed the area for the dash north in direct command of five warships.

The operational plan called for the group to approach Munda from the south, the only area accessible from the sea, and turn parallel to the coast before opening fire. After an hour’s barrage, the force would begin the journey home to be largely out of harm’s way by morning light.

At 8 pm, Task Force 67 split into two groups at a position southwest of the Russell Islands. The bombardment force consisted of the light cruisers Nashville, Helena, and St. Louis and the destroyers Fletcher and O’Bannon. Admiral Ainsworth chose the three cruisers based on flag facilities, radar equipment, and available ammunition; he used Nashville as his flagship. The remaining cruisers and destroyers of the task force would remain on patrol in the Guadalcanal area to ensure the safe departure of the transports.

The ships of the bombardment force were operating in the dark as they sped toward Rendova at 26 knots. Knowing full well that secrecy was the key to the success of his mission, Ainsworth was careful to keep the ships well clear of coastal areas and potential Japanese lookouts, and his navigators used radar fixes and echo-ranging gear to keep the ships away from known coral reefs.

The weather conditions seemed favorable to hide his approach. “The night of January 4 was very dark with an overcast sky and passing showers,” Ainsworth recalled. A radar-equipped Black Cat flew just ahead of the force, searching for any sign of the enemy.

Also in the air were two additional Black Cats to act as gunfire spotters. After searching the area around Rendova, the planes took station over Munda and began to harass the airfield as they had done the previous two nights and again drew heavy antiaircraft fire from the ground below.

“Each Black Cat had orders to drop flares individually and to cease illumination at zero hour minus 45 minutes,” reported Aviation Officer Crowley. “This was designed to give our surface force a well-silhouetted area as they rounded the west end of Rendova and, at the same time, to avoid illuminating our own ships when they came into range.”

Relying on Radar

Just after 11:30 pm, each of the three cruisers, starting with Nashville, catapulted off a float plane. “These planes carried four flares each and were for standby purposes only,” Ainsworth wrote. “They had orders to keep behind Rendova Island and over Blanche Strait. When the bombardment started, they were to keep to seaward and over our formation to warn us of the approach of enemy surface forces, and to warn our ships should they seem to be running into navigational dangers.” With the operation taking place deep in Japanese-held territory, the admiral wanted to take every possible precaution against being surprised by the enemy.

The weather conditions that helped to hide the approach of Ainsworth’s force now changed to favor the bombardment.

“At this time a black rain cloud hanging in the direction of Munda was moving slowly to the eastward and stars were dimly visible overhead,” the admiral wrote. From his position aboard Nashville, Ainsworth could see that the navigational setup was unfolding well. “Rendova Island came up distinctly on our starboard hand and approximate tangents could be taken on the entrance to Blanche Strait. The land masses showed up beautifully on the SG radar as we closed Banyetta Point.” Jutting out into the sea, the point was the westernmost extension of Rendova.

The final advance to Munda needed to be carefully executed so the ships could gain the proper firing position and steer clear of the dangerous rocks and reefs that lay just ahead; the submarine Grayback was positioned about two miles northwest of Banyetta Point to aid in the navigation process. During the critical last stage of the approach, crewmen aboard Nashville worked diligently to ensure the flagship remained exactly on course.

As Nashville approached Banyetta Point, her radar showed the area ahead and to the west to be clear. The flagship blinked a message for the other ships to spread apart for the final approach to the firing point.

Rounding Banyetta Point at exactly eight minutes after midnight, lookouts immediately spotted Grayback about 4,000 yards off Nashville’s starboard bow––positioned exactly as required by the plan. The cruiser and submarine exchanged brief acknowledgements by blinker, making sure that no messages flashed in the direction of land. At the closest point, Nashville passed within 2,100 yards of Grayback.

After passing the submarine, the bombardment force slowed to 18 knots and changed course to starboard. The ships were now pointed almost directly toward Munda. “After approaching and rounding Banyetta Point, the ship’s position was plotted almost exclusively from bearings and ranges from the SG radar,” Spanagel explained. Visual fixes later verified the movements as accurate.

About 15 minutes after midnight, lookouts aboard Nashville reported seeing flares over the Munda airfield. Ten minutes later, planes were sighted off the flagship’s starboard beam, followed almost immediately by gunfire near the beach. Crewmen aboard the flagship assumed friendly planes were drawing the unwanted attention of Japanese gunners.

The destroyer Fletcher led the formation during the crucial final approach to the firing line. The area around Munda Point was clearly defined on Nashville’s radar scope with the outlying rocks and reefs shown to be seven or eight miles away from the cruiser. Banyetta Point was plotted off the starboard side. The radar scope and plotting provided an accurate picture of the flagship’s current location and confirmed that the force was proceeding on the planned course.

The bombardment plan called for each cruiser to fire for 10 minutes while traveling along a three-mile firing line. Once shells were seen to land in the center of the target area, the ship would shift to rapid fire and walk salvos along a predetermined area. As one ship’s fire ceased, the next would start. The two destroyers were to fire in tandem after the cruisers to conclude the bombardment.

“A Beautiful Display of Fireworks”

Just before 1 am, Nashville turned onto the firing line. Her speed had slowed to 18 knots, down from the 25-knot clip attained during the final approach to the area, and the sharp turn to port put her on a parallel course to Munda.

At about the same time, the Black Cat observation plane moved into position over the airfield. “Mark. Mark. Mark” was broadcast over the spotting frequency to signify the plane was in position. A few minutes later, the flagship’s main battery guns opened fire with a thunderous roar and a volley of six-inch shells streaked out into the black night.

The flagship was aiming at the center of the runway with an initial range of 13,400 yards. An observer in the Black Cat above quickly radioed down an adjustment, “Up 500, no change in deflection.” The second salvo appeared to be on target and “No change” came down from the spotter.

The cruiser sent additional salvos in various directions along the runway and adjoining areas. Each time her six-inch guns roared, 15 130-pound shells lashed out into the night. When Nashville switched to rapid-fire mode, her guns sent a torrent of shells raining down on Munda.

The shelling was a spectacular sight to observers aboard the other American ships. “The bombardment afforded a beautiful display of fireworks from seaward and evidently looked very good from aloft, to judge by the remarks from the spotting plane,” Admiral Ainsworth observed. “The tracers were beautifully bunched for the 15-gun salvos, and when the cruisers took up continuous rapid fire, the stream of tracers looked as though were playing a hose on the target area.”

Shooting at Shadows

Nerves became tense when lookouts aboard the destroyer Fletcher suddenly reported a large ship dead ahead. The vessel looked to be 4,000 to 5,000 yards away. Although multiple lookouts confirmed the sighting, the destroyer’s radar did not. Thinking the device was malfunctioning, a radar operator shook his fist and yelled at the screen. The sighting was immediately reported over TBS radio to Admiral Ainsworth.

As Fletcher turned, however, the mysterious vessel seemed to move in the same direction, although the target angle remained the same. “This was the first intimation to all hands that something was screwy in the picture.…” Briscoe continued. Torpedo fire was held while the situation was sorted out. The target suddenly disappeared before any decisions could be made. The men aboard Fletcher soon realized they were seeing the shadow of their own ship illuminated in the light haze by the light cruiser’s gunfire. Their conclusion was clinched when the target’s disappearance was determined to have coincided with Nashville’s cease firing and reappeared as St. Louis started shooting.

The destroyer was not the only ship of the bombardment force to see a phantom target. Lookouts aboard Nashville later spotted what was thought to be a torpedo boat closing fast off her starboard bow. The secondary guns quickly opened fire, sending 10 rounds of 5-inch streaking toward the reported target before it was determined to be a false alarm.

“This matter of firing at one’s own shadow is much more real than can at first seem possible,” Ainsworth rationalized. “With everyone on their toes and all lookouts alerted, we are all prone to see things which do not exist, and these black shadows reflected on cloud masses near the horizon certainly appear to be enemy ships.” It was just another experience in the fog of war.

The St. Louis Joins the Barrage

At 1:13 am, Nashville ceased fire and increased her speed to 20 knots. Her turret crews worked through some minor gun problems but managed to hurl 853 6-inch rounds at Munda. The only causalities aboard the flagship were a burned hand suffered by a gunner in Turret Two and some damage to communication equipment.

At almost the same time that Nashville stopped shooting, St. Louis opened fire. Her first few salvos overshot the runway and were wide to the right. The spotter above radioed several requests to shift fire to the left. Six-inch shells were soon raining down on the runway and a report of “No change” came from the spotter.

“It is estimated that this ship placed 65 percent of its ammunition in the target area,” aerial observer Crowley reported. Several large fires started near the edge of the airfield and continued to burn throughout the remainder of the mission.

While Nashville and St. Louis pounded the airfield, the Japanese defenders briefly attempted to retaliate, with most of the fire seemingly directed at St. Louis. “This return fire was detected by seeing the tracers rise from the vicinity of the airfield, and occasionally a slight flash could be seen as the guns fired,” observed Captain Colin Campbell of St. Louis.

None of the fire came close to the ship and no splashes were seen. “It is concluded, from the path the enemy trajectories took, that all their fire fell considerably short,” Campbell reported.

“It is Beautiful, Excellent, Excellent!”

At 1:25 am, it was time for the third light cruiser to open fire. Helena’s first salvo fell short and to the left of the target. The Black Cat observer radioed a series of spots to get the ship’s fire on target. About 10 minutes later, a spotter was heard to exclaim, “It is beautiful, excellent, excellent!”

Adjustments from the various reports now had the shells raining down on the assigned target area. “This ship covered Munda Point thoroughly, causing a large explosion,” reported airman Crowley. “They sprayed the beach area to the north of the point and caused a large explosion on the hill to the north of the runway.” From his vantage point, it looked as if about 80 percent of the light cruiser’s shells landed in the target area.

After moving out of position to chase down the phantom target, Fletcher eventually took up station behind Helena; the destroyer O’Bannon was about 750 yards farther astern.

When the light cruiser’s firing stopped, it was time for the two destroyers to take center stage, and both opened fire simultaneously at 1:40 am. The first salvoes were directly on target. Subsequent 5-inch shells landed on beach areas north and south along the coast. Gunfire from the destroyers touched off a large explosion, possibly from an ammunition dump.

By the time the bombardment ended at 1:50 am, about 4,000 shells had been hurled at Munda. As soon as the firing stopped, Fletcher and O’Bannon increased speed to 32 knots and raced to get ahead of the cruisers. The formation quickly closed ranks, narrowing the distance between the ships. The approach to Munda had been undetected and the bombardment had apparently taken the Japanese by complete surprise. Admiral Ainsworth now had to return to the Guadalcanal area with an alerted enemy on the hunt.

Search-and-Destroy

The bombardment force began zigzagging and making occasional course changes shortly after turning south. As with the approach to Munda, Black Cats searched ahead of the ships during the remaining hours of darkness. Wanting to avoid any potential trouble, Ainsworth steered the force well clear of a reported cluster of Japanese midget submarines near the south end of New Georgia Island.

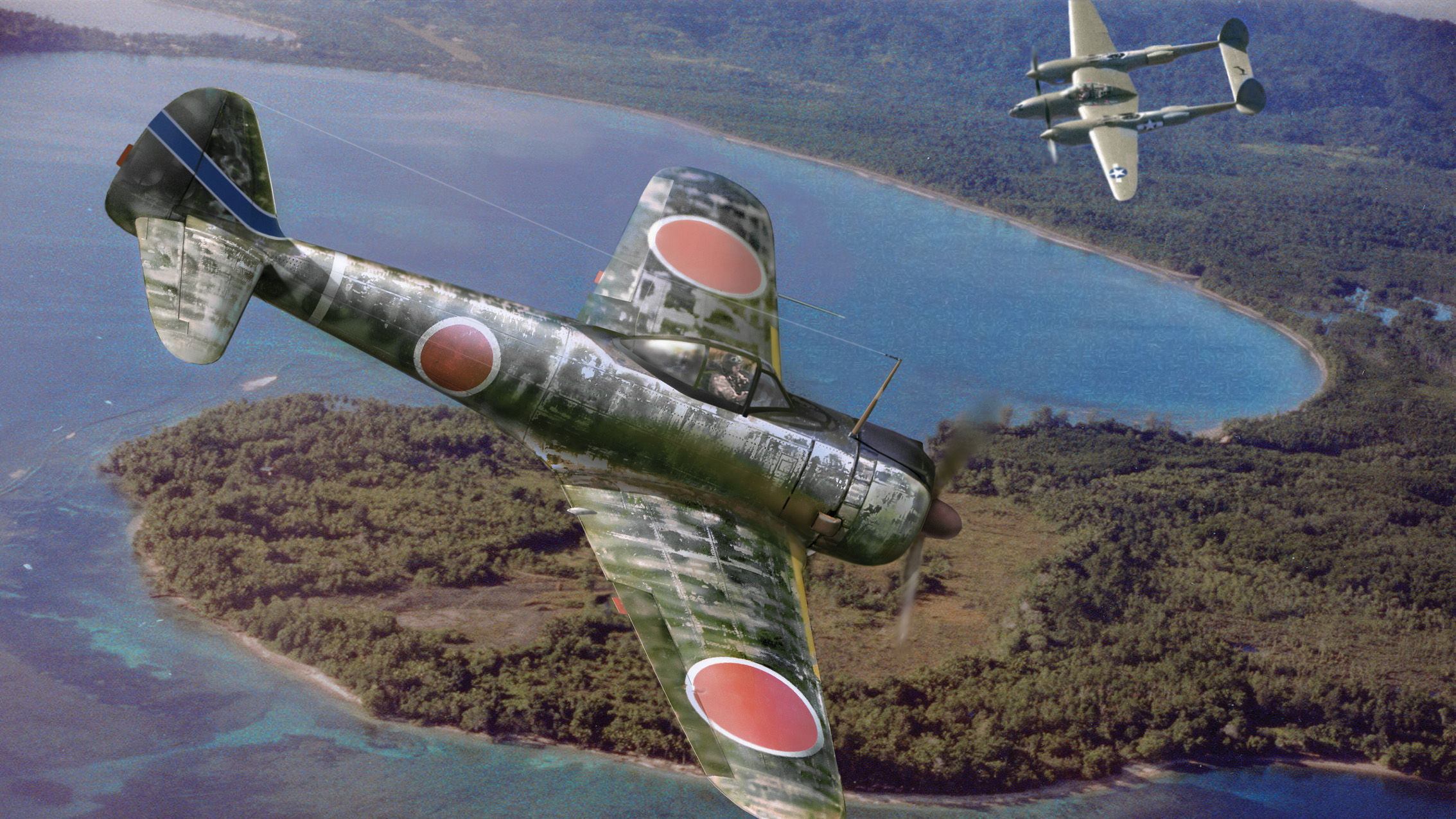

Determined to find the American task force that carried out the surprise intrusion, Japanese air commanders ordered extra reconnaissance planes airborne during the morning hours. The effort was later bolstered when a group of 14 Zero fighters and four Val dive bombers was dispatched on a search-and-destroy operation.

Lookouts and radar operators aboard the bombardment ships kept careful watch as the task force sped out of Japanese waters; American air cover was en route in the form of four Wildcat fighters dispatched from Henderson Field on Guadalcanal.

A group of approaching planes was detected on radar scopes at about 7 am when the ships were almost 30 miles south of the Russell Islands. Quickly identified as friendly, the planes took station overhead as the bombardment force reduced speed to 28 knots.

The arrival in the Guadalcanal area marked the end of the first leg of the journey home for the bombardment force. Admiral Ainsworth moved toward a rendezvous with the remaining ships of Task Force 67. Under the command of Rear Admiral Mahlon Tisdale, the cruisers Honolulu, Achilles, Columbia, and Louisville spent the night patrolling near Guadalcanal in the company of three destroyers. The two groups made visual contact with each other at 8:15 am about 30 miles southwest of Guadalcanal and were operating in close proximity about 45 minutes later.

The cruisers of both forces needed to slow in order to recover float planes. For Ainsworth’s force it was the three seaplanes launched during the bombardment. The trio went to Tulagi at the conclusion of the mission before taking flight to return to the cruisers. Admiral Tisdale’s ships needed to recover the same number planes from antisubmarine patrol and to launch replacements.

The Japanese search-and-destroy group stumbled upon the unsuspecting warships during the critical time of aircraft recovery. The enemy planes suddenly approached the force from the north at a high rate of speed, taking the warships by complete surprise.

The suddenness of the encounter left little time for any of the warships to react before the four Val bombers started into their steep attacking dives. The planes approached Admiral Tisdale’s cruisers, heading directly toward the lead ship Honolulu. The light cruiser started a sharp turn just as three bombs straddled her. The first projectile sent up a tower of water 25 yards off her port bow; the second and third bombs landed a similar distance off the starboard side. An assortment of antiaircraft guns opened fire after the planes passed over the ship. One Val was seen to be riddled with bullets.

At least one bomber had its sights on the second ship in the column, the New Zealand light cruiser Achilles. Lookouts aboard the vessel sighted the planes moments earlier, but mistook them for American fighters. When the hostile actions revealed the planes to be enemy, the New Zealand sailors raced to man antiaircraft guns. Only a few guns were able to fire before a bomb landed on Turret Three. The blast wrecked the gun house and killed 13 men.

After attacking the two lead ships, the planes briefly flew parallel to the column of cruisers, taking fire from both Columbia and Louisville before veering toward Admiral Ainsworth’s ships. Both Helena and St. Louis sent up a wall of antiaircraft fire at the approaching planes.

The two cruisers, however, did not come under bomb attack as the planes flew past the stern of Helena before turning sharply to the north to depart the area. One Val crashed in flames as a result of antiaircraft fire, possibly from Helena. A second plane was splashed by Wildcat fighters, and the air attack was over almost as quickly as it had begun.

A Temporary Success

The episode marked the end of the mission to bombard Munda. The fire aboard Achilles was quickly doused and the ship kept her position in column. The combined force patrolled in the immediate area before heading south and entering the anchorage at Espiritu Santo, New Hebrides, just before 9 am on January 8.

Admiral Ainsworth had successfully led the first major American seaborne intrusion into the Japanese-held waters of the central Solomons.

“Reports from our spotting Catalina over Munda indicate that the bombardment was successful, approximately 80 percent of the fire taking effect in the target area and the remainder being partially effective near its boundary,” he later wrote.

The cruiser commanders shared Ainsworth’s belief that the operation was a large success and felt each of their respective ships performed exceptionally well. Captain Campbell of St. Louis rated the performance of his gun crews and fire control men as simply “Excellent.”

All combined, the three cruisers hurled 2,773 6-inch shells at the enemy; the destroyers added 1,376 5-inch rounds. American planes flying over Munda the next morning reported substantial damage to the airfield and inconsequential antiaircraft fire.

But success was short lived. Although the heavy naval shelling destroyed 10 buildings and killed or injured 30 men, the Japanese were able to repair the runway in a mere two hours, and the airfield was reportedly in use 18 hours after the attack.

The struggle over Munda continued well into 1943. Although pummeled by air and sea, the determined Japanese kept the airfield operational for all but short stretches of time. Munda finally fell after American ground forces captured it on August 5, 1943, following the hard-fought invasion of New Georgia.

Major General Oscar Griswold, commander of the Army’s XIV Corps, personally radioed Admiral Halsey the good news. “Our ground forces today wrested Munda from the [Japanese] and present it to you … as the sole owner….”

Eight days later, the first Allied plane landed on the runway.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments