By Victor Kamenir

After decisively crushing Austrian and Russian armies in the 1805 campaign, French Emperor Napoleon became the undisputed master of Central Europe. One of his first acts was to dissolve the antiquated Austrian-led Holy Roman Empire and reform smaller German states into the Confederation of the Rhine, with himself as its protector. Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm III, who did not join the 1805 campaign, watched with a jaundiced eye Napoleon’s growing power and influence. Napoleon, who treated Friedrich Wilhelm with a thinly veiled contempt, attempted to play Prussia against England—his implacable enemy—by offering each the Principality of Hanover, which he had occupied in 1803. The affront to Prussian pride became too much when Napoleon ordered the kidnapping and execution of Prussian nationalist Johann Philipp Palm in August 1806 for publishing a pamphlet strongly critical of Napoleon and conduct of his army in occupied German territory.

Friedrich Wilhelm haughtily demanded that Napoleon dissolve the Confederation of the Rhine and withdraw his troops from all German territory. When Napoleon rejected the demands, a new anti-Napoleon coalition was formed on September 15. The Fourth Coalition was composed of Prussia, Russia, Saxony, Great Britain and Sweden. Young officers of the Prussian Royal Guard arrogantly sharpened their swords on the steps of the French embassy in Berlin, and the Prussian army, which was by then past its prime, marched off to war.

Rashly advancing on its own without waiting for its Russian allies to come up, Friedrich Wilhelm’s overconfident and outdated Prussian army was soundly defeated by Napoleon on October 14, 1806, at the twin battles of Jena and Auerstadt in Thuringia. In the aftermath of the battle, only Lt. Gen. Anton L’Estocq’s corps survived. It marched east to link up with the Russian army, which was just beginning to assemble for a campaign against the French.

By the close of October the Russians had arrived in Poland. To prevent the Russians from reaching the Warsaw on the Vistula River and prevent them from linking up with L’Estocq’s corps, Napoleon set his Grand Armee on a course towards the Polish capital. French cavalry entered Warsaw on November 28 after brushing aside a screen of Cossacks the previous day.

Facing superior numbers, the four leading Russian divisions that constituted the Russian First Army under Field Marshal Mikhail Kamensky began falling back to link up with the Russian Second Army under Maj. Gen. Karl Gustav von Bagovout, which included L’Estocq’s Prussians.

After a month of marching, countermarching and a several sharp skirmishes, Kamensky’s First Russian army withdrew to Pultusk. Kamensky, the 72-year-old overall commander of the Russian forces, was stricken by illness and incapacitated by old age. He therefore turned over command of the army to Bagovout. Before departing the army, Kamensky ordered General of Cavalry Levin von Bennigsen, the second-in-command of the First Army, not to engage the French army until he was reinforced.

Bennigsen and Bagovout despised each other. Refusing to acknowledge Bagovout’s authority, Bennigsen staked his career on a bold move in which he decided on December 26 to fight the French army at Pultusk on his own. Although the fight was indecisive, Bennigsen claimed victory. In the aftermath of his apparent success, Tsar Alexander I gave Bennigsen overall command of the Russian forces.

Russian withdrawal continued the next day, with the French in close pursuit. But heavy rains turned the roads into an impassable sea of mud, bringing operations to a close for the time being. “The terrible roads and bad weather have persuaded me to enter winter quarters,” wrote Napoleon.

The two armies that settled into their winter cantonments were hungry, exhausted, and poorly clad from constant marching and fighting. “Our army was in dire need of provisions,” recalled Russian Colonel Aleksey Yermolov. “Frequently, troops were sent not where they were most needed, but where it was possible to find better food.” Supply situation on both sides deteriorated to such extent that Napoleon estimated at least 40 percent of his troops were absent from their units. Many of those absent were marauding through the countryside.

Despite a temporary loss of discipline, Napoleon’s Grand Armee was in its prime as a result of hard training. The Grande Armee was composed of corps d’armee, each a miniature army commanded by a marshal, composed of two or more divisions of infantry and a brigade of light cavalry, with attendant artillery, engineers, and supply troops. The Grande Armee also had a large cavalry reserve and an Imperial Guard, which also was part of the reserve. The army was still homogenously French. By 1806 it was not yet diluted by foreign conscripts from Germany, Holland, Switzerland, and other occupied areas. Senior leadership was skilled and confident, and the rank-and-file was capable and eager. Most importantly, the officers and rankers had an unshakable confidence in Napoleon.

In contrast, the Russian army had its share of problems despite recent reforms. On the whole, it was a cumbersome organization drowning in minutiae. The soldiers were hardy and stoic but virtually illiterate and discouraged from showing initiative. The officer corps was brave and willing, but aside from aristocratic members of the high nobility was poorly educated. Some of the best officers were of foreign extraction, Germans of all stripes in particular. Russian divisions, a corps in all but name, were not permanent organization, but ad-hoc formations formed and reformed at the commander’s whim. Lacking the brigade-level command element, each regiment had to be issued orders separately, complicating command-and-control function. One of the Russian army’s strengths was its cavalry branch, which was well mounted. Similarly, the artillery was of good quality although not quite as well drilled as the French. The administrative and commissariat functions were abysmal. For these reasons, Russian soldiers often had to fend for themselves, marauding through both friendly and enemy countryside with equal enthusiasm.

In the last week of January 1807, Bennigsen launched a surprise attack in the dead of winter against the French left flank. His attack might have succeeded had the Russians not encountered French troops from Marshal Michel Ney’s VI Corps, which moved forward from their bivouacs in search of supplies and better bivouac areas. Leaving L’Estocq with his 9,000 Prussians to hold the allied right flank, Bennigsen decided to fall upon Marshal Jean Bernadotte’s I Corps, which was in an isolated position on the French left. After defeating the French I Corps, he would then cross the Vistula River in order to sever Napoleon’s supply lines.

But Bernadotte slipped away. Napoleon, who learned of the Russian movements on January 27, initiated a maneuver in which he sought to encircle and destroy the Russian army. Bernadotte was ordered to continue the retreat so that the other corps could come up against the Russian flank in a manoeuvre de derrière. Napoleon typically used this maneuver, which translates to “move onto the rear,” when he was numerically superior to the enemy.

The main force of Napoleon’s Grand Armee marched in three columns. The right column consisted of Marshal Nicholas Davout’s III Corps. The center column was composed of Marshal Joachim Murat’s Reserve Cavalry, Marshal Jean-de-Diu Soult’s IV Corps, Marshal Pierre Augereau’s VII Corps, and the Imperial Guard. The left column consisted of Marshal Ney’s VI Corps. Ney had orders to keep steady pressure on L’Estocq to prevent him from linking up with the Russians.

The success of the French offensive depended on maintaining operations security. However, Cossacks intercepted a copy of the orders being carried by courier to Bernadotte. The Russians initially thought the captured dispatches were part of a ruse. But when a second rider with an identical copy of orders was captured, Bennigsen immediately began withdrawing.

Russian rearguard detachments under Lt. Gen. Prince Pyotr Bagration and Maj. Gen. Barclay de Tolly were constantly engaged to keep the French at bay. Bennigsen ordered Bagration to withdraw as slow as possible to buy the army time to fall back to the town of Preussisch-Eylau which Bennigsen selected as the place to give battle. After successfully delaying the French, the rearguard caught up with the main army on February 7 just east of Eylau, which lay 30 miles south of Konigsberg.

Napoleon arrived shortly behind the Russians, but decided not to occupy Eylau that night, his troops exhausted from constant marching and fighting. “I was advised to take Eylau tonight, but besides the fact that I do not like night fighting, I don’t want to move my center too far forward until Davout’s arrival, who is my right flank, and Ney, who is my left,” Napoleon told Marshal Augereau. Accordingly, Napoleon dispatched messengers to Ney and Marshal Nicholas Davout, who commanded the III Corps, with urgent orders to hasten forward.

Napoleon’s caution came to naught. A small convoy carrying Napoleon’s personal baggage had entered Eylau unaware that the emperor did not intend to occupy the town that night. A Russian patrol happened upon the lucrative target and only the bravery of a small detachment of Imperial Guard cavalry prevented the emperor’s personal effects from falling into Russian hands. Hearing the sound of fighting, Marshal Soult’s pickets hurried forward to engage the Russians. “The enemy generals, thinking that the French wished to take possession of Eylau, sent up reinforcements on their side, so that a bloody engagement took place in the streets of the town,” wrote Captain Jean-Baptiste Marbot, who was Augereau’s aide-de-camp.

Bagration’s rearguard, which was composed of six infantry regiments, four cavalry regiments, and 40 artillery pieces, became fully engaged. Bennigsen reinforced Bagration with troops from the 8th Division with orders to push the French out of Eylau. General Yevgeni Markov led two infantry regiments in a bayonet charge into the town, while a dragoon regiment clashed with the French outside the town on a frozen lake.

Augereau and Soult fed more troops into the action, which was reciprocated by Bennigsen. Both sides continued to feed more men into the expanding fight. The town changed hands several times, with darkness bringing a halt to the fighting and leaving eight thousand French and Russians dead and Eylau in French possession. Barclay de Tolly, who was one Russia’s most capable commanders, suffered a severe wound to his arm and was evacuated to Konigsberg, thus denying Bennigsen his considerable talents the next day. At nightfall, Bennigsen placed the 4th Division and 40 more cannon between Eylau and the main Russian position to prevent a sudden attack by the French before the daybreak.

During the night the temperature fell below freezing and soldiers on both sides shivered in their bivouacs. The misery of the snowstorm was made worse by a shortage of supplies when the supply columns became bogged down as the marched along snow-choked roads.

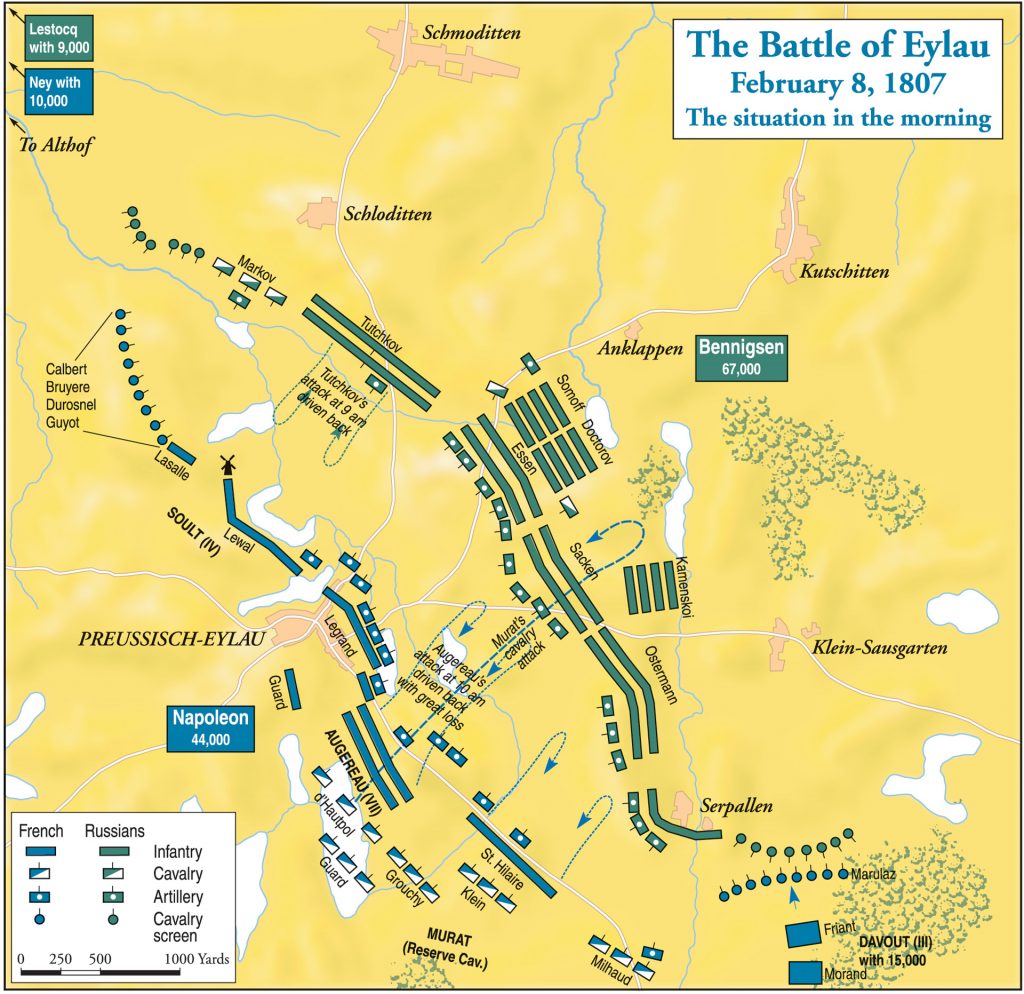

At dawn on February 8, the opposing commanders peered through the falling snow in an attempt to discern their opponent’s positions. Bennigsen deployed his 67,000 troops on a three-mile-long front. They arrayed themselves for battle in two lines along a low ridge east of Eylau, within a cannon shot of the town. Each regiment in the first line was deployed with two battalions in line and the third in column 100 paces to the rear. This allowed the third battalions of the first line to quickly reinforce the rest of the regiment. The second line was in battalion columns, where several regiments could quickly form a large column to reinforce the first line or to counterattack.

Lt. Gen. Nikolai Tuchkov was in charge of the north, right, flank near the Schloditten village with his own 5th Division and Maj. Gen. Aleksandr Markov’s light cavalry brigade in reserve. In the center was Lt. Gen. Baron Fabian von der Osten-Saken with his own 3rd Division, as well as Lt. Gen. Count Peter Essen’s 8th Division, with a reserve consisting of Maj. Gen. Andrei Somov’s 4th Division. In front of the Russian center, two jaeger regiments deployed as skirmishers. The Russians also deployed several 12-pounder artillery batteries on the hills opposite Eylau.

Lt. Gen. Count Aleksandr Ostermann-Tolstoi’s 2nd Division took up a position farther down the line. Bagovout’s 6th Division under anchored the Russian left flank near the village of Serpallen, with Maj. Gen. Count Nikolai Kamensky’s, the Field Marshal son’s, 14th Division in reserve. Bennigsen placed Lt. Gen. Dmitri Dokhturov’s 7th Division in reserve behind the center.

In addition to divisional artillery deployed along the line, as well as in reserve, three grand batteries were established to anchor the first line. The Russians established a battery of forty 12-pounders and twenty 6-pounders on the right flank to cover the road to Konigsberg. They placed a second battery of seventy 12-pounders in the center and another battery composed of forty 12-poundes near Klein-Sausgarten. A total of 430 Russian cannons faced 300 French guns. Bennigsen expected that L’Estocq’s 9,000-strong Prussian corps would arrive on the field of battle from the north.

Bennigsen entrusted Cossack Lt. Gen. Matvei Platov with command of all 10 Cossacks regiments in the army. This gave Platov a total of 2,500 sabers. Normally, a Cossack regiment numbered 500 men, but hardships of campaigning had reduced their numbers by half.

The ground between the two armies was cut by narrow streams and dotted with small ponds. Deep snow covered the frozen ponds, giving an appearance of level ground.

Napoleon had 45,000 French troops facing the Russians. Well aware of the paucity of his numbers, he scanned the horizon to the north and south anxious for the arrival of both Ney’s 14,500 men and Davout’s 15,000 troops.

Napoleon planned a double envelopment of the Russian army. He placed Soult’s corps minus one division on the left flank, Augereau’s corps in the center, and Soult’s third division under General of Division Louis St. Hilaire on the right. Augereau’s two divisions deployed in two echelons with General of Division Jacques Desjardins in front and General of Division Etienne Huedelet behind him. The left flanks of the two divisions rested on the church where Napoleon established his command post. Napoleon placed brigades of light cavalry on each flank. The cavalry force on the left flank included the 5th Hussar Regiment, as the Infernal Brigade. The Imperial Guard deployed near the Eylau cemetery, and Murat’s Reserve Cavalry behind Augereau.

Napoleon’s plans for the morning of February 8 called for Soult to pin down the Russian right until Davout’s arrival. Upon Davout’s arrival, Augereau’s corps and St. Hilaire’s division were to link up and crush the Russian left flank. Meanwhile, Murat’s Reserve Cavalry would stand by ready to exploit any breach. As usual, Napoleon held his valuable Guard in reserve for any unexpected developments. Ney’s expected arrival on the north end of the field would complete the French double envelopment. Napoleon wanted the Russians to believe that he had more troops on hand than he actually had that morning, so he positioned his Imperial Guard units farther forward than he normally did.

A sharp firefight erupted at dawn between French skirmishers and Russian jaegers in the center, shortly followed by Russian bombardment of Eylau and the French columns around it. A full-scale artillery duel was in progress by 8:00 am with cannonballs slashing through the falling snow.

“Devil knows, what clouds of cannonballs flew by, droned, showered us, jumped around me, were digging in all directions around closely formed masses of our troops and what clouds of shells were exploding over my head and under my feet,” recalled Captain Denis Davydov, Bagration’s aide-de-camp.

Despite the Russian army’s numerical advantage in artillery, their gunners were getting the worst of it. Although in many respects Russian artillery crews were as good as the French, the Frenchmen shot faster and more accurately at the exposed massed Russian formations, which were deployed devoid of any appreciable cover. Unlike the exposed Russians, many of the French troops were stationed behind the villages of Eylau and the Rottenen. Because of this, many of the Russian cannonballs either struck homes and buildings in the villages or simply fell short of their mark.

The vanguard of General of Division Louis Friant’s division of Davout’s III Corps was seen at mid-morning approaching from the south in the distance. Wishing to draw Russian attention from Davout, Napoleon ordered Soult to advance a short distance and occupy the windmill opposite Tuchkov’s position. Triggered by the French advance, Tuchkov advanced his infantry units. Heavy fighting erupted around the windmill-topped hill. In the ensuing clash of infantry, Soult’s troops were driven back almost to Eylau. Two Russian dragoon regiments were hot on the heels of the retreating French foot soldiers.

Noticing significant Russian reserves concentrating against Davout, Napoleon ordered Augereau’s VII Corps and St. Hilaire’s division to advance against Ostermann-Tolstoi in the Russian center. St. Hilaire was then to link up with Friant’s division in rolling up the Russian left flank. Augereau’s two divisions, which totaled 9,000 men, formed up south of the Eylau cemetery and bravely advanced into the swirling snow.

General of Division Jacques Desjardins troops were on the right and General of Division Etienne Huedelet’s men were on the left. A brigade in each division advanced in line, while the trailing brigade remained in column behind it. The columns could at any time shift into a square if suddenly attacked by Russian cavalry. Artillery from the VII corps unlimbered 400 yards in front of the cemetery to support the infantry.

Augereau’s divisions quickly lost their way in the blinding snow. Instead of striking Ostermann-Tolstoi’s division head on, they veered left into the waiting barrels of Sacken’s 70-gun grand battery. Cannon balls and grape shot tore into Augereau’s tightly formed divisions from pistol-shot range, knocking down whole files of men at a time. In several moments, Augereau’s corps lost thousands of men killed and wounded. Huedelete was wounded and Desjardins killed, with Augereau suffering a light wound. Crossfire from French and Russian artillery tore into the flanks of Augereau’s columns, heaps of dead bodies piling up in small mounds.

Following on the heels of the Russian artillery salvos were Russian infantry with lowered bayonets. A vicious fight that lasted for half an hour flared up in the Russian center. At close range, once their muskets were fired, men tore at each other with bayonets, clubbed muskets, rocks, and fists.

“Bayonet and sword played, luxuriated and drank their fill,” wrote Davydov. Bloodied units reeled back, reformed and rushed into the maelstrom again. The Moscow Musketeer Regiment, which spearheaded the counterattack, suffered 668 men killed and 173 wounded, according to its battle report. Disproportionate number of killed versus wounded attested to the ferocity of the fighting.

Following close on the heels of the Russian infantry were massed charges of Russian dragoons and cuirassiers. These in turn were followed by Cossacks with lances lowered, which attacked in line instead of their typical swarms. In an impetuous charge, the Russian cavalry reached Augereau’s starting positions where several French artillery batteries were left unprotected. Some gunners cut the traces of limber horses and were able to get away, while the rest were put to the sword. Unable to take the guns with them, a number of Russian troopers chopped up the wheels of several of the guns, which rendered them unusable for a time.

Taking advantage of Augereau’s rout, Russian reserves under Dokhturov advanced into a gap that had opened in the French center. Dokhturov’s attack drove Augereau even further back, toward the Eylau cemetery where Augereau attempted to rally several thousand men. In the confusion, the musketeers of the French 14th Line Regiment found themselves cut off on a small hillock. The regiment’s color guard defiantly waved the Eagle-topped flag to show that the regiment was still in action and needed immediate aid.

“The Emperor, touched by the devotion to duty of these brave men, decided to attempt their rescue,” wrote Marbot. “He told Marshal Augereau to send an officer with orders to them to quit the hillock, form a small square and withdraw towards us.” The Cossacks intercepted and killed two officers sent to the beleaguered regiment. With no one else to go, Marbot set off on the mission. Putting his spurs to his mare, he miraculously made it to the 14th Line unscathed.

When Marbot relayed Napoleon’s orders, the regimental commander sadly shook his head, “I can see no way of saving the regiment,” he said. “Return to the Emperor and give him the farewells of the 14e Regiment de Ligne which has faithfully carried out his orders, and take him the Eagle he gave which we can no longer defend; it would be too terrible to see it fall into enemy hands during our last moments.”

Reverently taking the regiment’s French Imperial Eagle standard, Marbot rushed back, but was wounded and fell off his horse unconscious. He came to hours later, stripped naked by the Cossacks and with the Eagle gone. The remaining soldiers of the 14th Line Regiment perished in the wake of a Russian bayonet charge.

A strong Russian column had reached Eylau. Napoleon had established his command post near a church tower. To protect the emperor, two Guard battalions rushed forward to engage the Russians. Their sacrifice saved Napoleon.

By that time, Russian artillery fire was threatening the serried ranks of the Guard. An exploding shell showered Colonel Louis Lepic with a mixture of snow and dirt. Wiping his face, the colonel looked back to discover his elite troopers of the Grenadiers a Cheval de la Garde Imperiale regiment ducking their heads under cannonballs whistling just above their tall bearskin hats. “Heads up, gentlemen,” shouted Lepic. “These are cannonballs, not turds!”

The Grand Armee’s situation had grown increasingly dim by late morning. On the left, Soult was entangled with Tuchkov, unable to make progress. In the center, Augereau’s corps was severely mauled and its bloodied survivors were being rallied at Eylau. St. Hilaire’s division reached Ostermann-Tolstoi, but was unable to dislodge him by itself. In addition to the Imperial Guard, the only uncommitted troops available to Napoleon were Murat’s Reserve Cavalry.

Pointing at the sea of glittering Russian bayonets, Napoleon asked his brother-in-law, “Will you let those men devour us?” Murat rode off to assemble his cavalry for an attack. Thirty minutes later more than 10,000 troopers moved forward. Murat waved his riding crop in the air as he led them towards the Russians. Each regiment formed into line. They made a stirring sight. Armored cuirassiers under generals Jean-Joseph d’Hautpol and Emmanuel de Grouchy, dragoons under Brig. Gen. Louis Klein with their horsetail-crested helmets, and green-coated chasseurs a cheval. As they charged, Russian artillery fire and musket fire emptied many saddles and sent countiless horses tumbling to the ground.

Murat’s troopers fought their way through Dokhturov’s frontline troops, who were withdrawing from Eylau, but was brought up short by the Russian second line and artillery. The veteran cavalry commander rallied his men. They turned around and cut their way back through the first Russian line again, hotly pursued by Russian cavalry. During the confused fighting in this sector, two squadrons of French cuirassiers became separated. Russians shouted for them to surrender, but they cut their way out with the Cossacks following close behind.

Napoleon directed the light cavalry of the Guard under Marshal Jean-Baptiste Bessieres and Lepic’s heavy cavalry to cover Murat’s withdrawal. The gallant cavalry charge cost the French more than 1,500 troopers. Among the dead was General of Division Jean-Josef d’Hautpoul, the commander of the 2nd Cuirassier Division, who had been killed by a cannonball. The sacrifice of these elite cuirassiers allowed the beleaguered infantry of Augereau and Soult to reform. It also bought time for Davout to bring up the bulk of his corps. Although the moment seemed right to send in the infantry of the Imperial Guard, Napoleon hesitated for he knew that the Prussians might arrive at any moment and fall on the French left. What is more, Ney’s VI Corps was yet to arrive on the field.

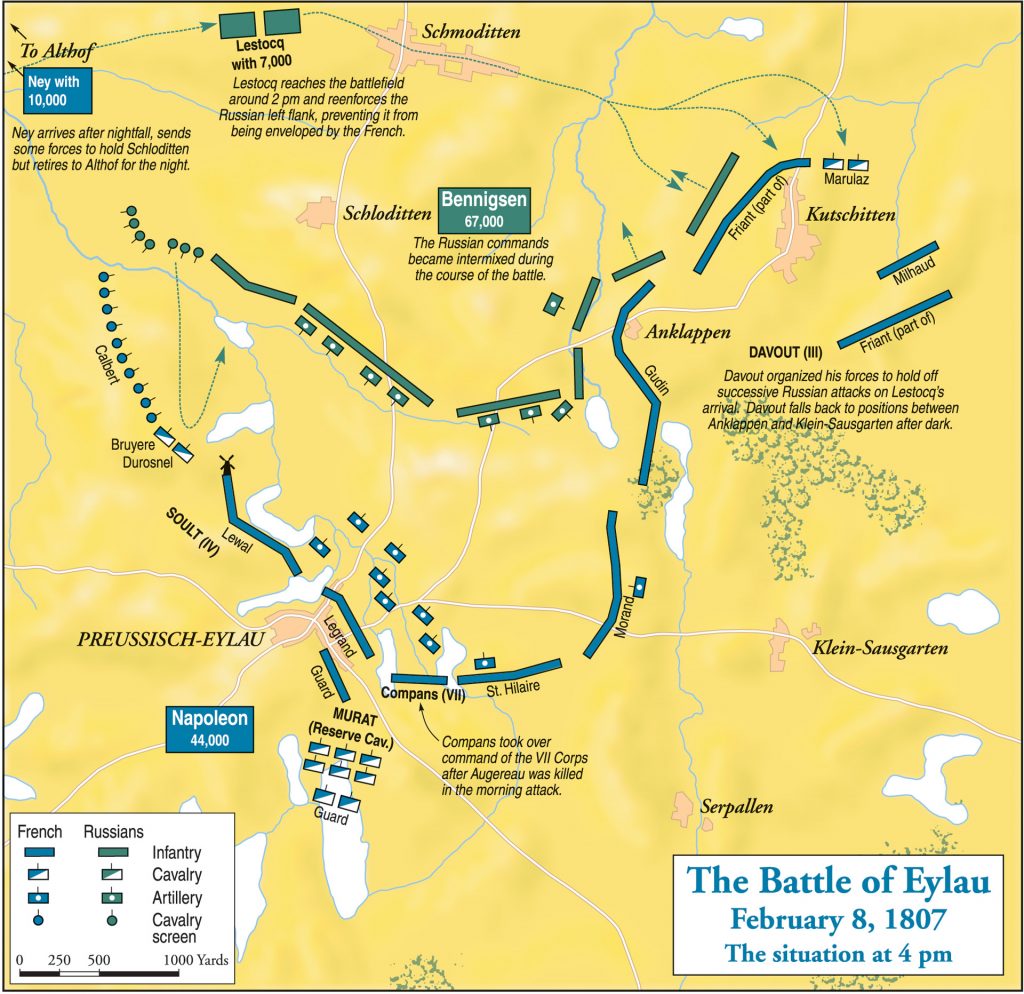

By 1:00 pm Davout had deployed his III Corps. Napoleon ordered the veteran commander to attack Bagovout’s exposed left flank near the villages of Klein-Sausgarten and Serpallen. St. Hilaire’s division formed on Davout’s left flank. Behind them were the rallied survivors of Augereau’s Corps and the reformed ranks of Murat’s Reserve Cavalry.

Russian cavalry launched repeated harassing attacks against Davout’s advancing columns of infantrymen. This forced the French foot soldiers to halt and form squares to repulse the enemy cavalry. With great effort, Davout’s troops, which were supported by the corps artillery, drove the Russians from the heights overlooking Klein-Sausgarten. They then ejected the Russians from the village. Davout’s corps artillery played a crucial role in the success of the attacks.

The fighting near the villages of Klein-Sausgarten and Serpallen shifted back and forth throughout the early afternoon. The villages exchanged hands multiple times. Although his divisions suffered heavy losses, Davout pressed on towards the Anklappen Woods. In so doing, he threatened to get behind troops in the Russian center.

Bennigsen shifted troops to his left flank to avoid encirclement. The stakes were high, for if he did not take immediate action, the Russian army would be cut off from the retreat route to the Russian border.

As the troops on Bagovout’s left flank slowly fell back to Kutschitten, the youthful artillery commander Maj. Gen. Aleksandr Kutaisov rode to the right flank to gather guns to bolster the left flank. On his own authority, Kutaisov ordered two horse artillery companies under Colonel Aleksey Yermolov to follow him. On their way south Yermolov ordered another horse artillery company to join him. Arriving in the nick of time, Yermolov’s gunners unlimbered 36 guns. These Russian guns fired at point-blank fire into Davout’s foot soldiers. To show his men that there would be no retreat, Yermolov ordered all the horses to be taken to the rear.

The troops on the Russian front line were barely hanging on by mid-afternoon. Because of the French attacks, their line was by then L-shaped. The soldiers of the Russian divisions on the left flank fell back past Anklappen. The Russian center, held by the troops of Dokhturov and Essen, also began falling back.

Bennigsen rushed off to find the Prussians and hurry them along. In his haste, the Russian commander failed to advise the generals of his divisions of his departure. The bewildered subordinate commanders did the best they could without direction from above for nearly an hour as the crisis facing the Russian army deepened. After capturing the villages of Klein-Saustargten, Anklappen, and Kutschitten, Davout placed his artillery to rake the Russian left flank and rear. Just at that moment, the Prussians arrived on the battlefield from the direction of Althof. They had succeeded in breaking contact with Ney’s vanguard in order to reinforce the collapsing Russian line. Bennigsen directed the Prussians into action where they were most needed

Traversing the battlefield behind the Russian right flank, the Prussian columns struck Davout’s exposed right flank near Kutschitten. When Davout’s artillery turned on L’Estocq, Yermoolov engaged them in counter-battery fire, Russian gunners advanced the guns by pulling ropes after each volley. Exhausted troops, who were emboldened by the new arrivals under Kamensky and Bagovout, found strength to attack alongside the Prussians.

Under the weight of the combined assault by Russian and Prussian forces, Davout was forced to cede the ground for which he had paid so dearly. The Iron Marshal, as he was known, fought for every inch of the ground, having turned Anklappen into a bastion ringed with musket fire. The French fought fiercely and abandoned the Anklappen after Yermolov’s guns fired at point-blank range into the burning village.

The situation for the French grew increasingly grim when Ney’s VI Corps, having brushed aside L’Estocq’s rearguard, finally appeared to the northwest at 7:00 pm. The fiery red-headed marshal immediately hurled his troops into action. They succeeded in ejecting the Russians from Schloditten. But Tuchkov, who was reinforced by Essen’s division, counterattacked and retook the village at the point of bayonet.

Desultory cannonade continued sporadically until 10:00 pm and the fighting all along the line ground down to a halt after 14 hours of bloodletting. Tens of thousands of dead and wounded lay on the battlefield, steadily being covered by the falling snow. “What a massacre and without any good!” Ney said as he observed the blood-soaked field.

Battered units on both sides settled into their bivouacs, listening to the pitiful cries of the freezing wounded in the no-man’s land. As the survivors lit their camp fires, thousands of wounded men began crawling toward them and fleeting warmth. Adding to the misery of the wounded, local peasants came out of their hiding to loot the dead and the dying.

During the night Bennigsen held the council of war in the ruins of Anklappen. Despite several generals proposing to renew the struggle in the morning, Bennigsen made the decision to cede the field to the enemy and during the night the Russians units began departing the field. The French finally discovered the Russian retreat before dawn, but there was no chance the exhausted and blooded French could pursue. “Marshal, the Russians have done us great harm,” Napoleon said to Soult the following morning. “And we them, our bullets were not made of cotton,” Soult retorted.

Losses were almost crippling and it took both armies almost three months to recover and reorganize before hostilities flared up again. As was common, both sides undercounted their own loses and overestimated that of their enemies. The battle had been particularly costly for Napoleon. The French lost 25,000 men, while the Russians lost 15,000 soldiers.

But both Napoleon and Bennigsen deliberately misrepresented their losses to the respective nations. Napoleon remained on the battlefield for 10 days. “My Dear; I am still at Eylau,” he wrote on February 14 to his wife, Empress Josephine, “The country is covered with dead and wounded. It is the worst aspect of war. It is heartbreaking and my soul is oppressed at the site of so many victims.”

The two-day clash at Eylau was over. While it was a French tactical victory given that Napoleon had retained possession of the battlefield, it was strategically inconclusive. In the aftermath of the battle, though, both Napoleon and Bennigsen claimed victory.

For his part, Bennigsen considered fighting to a draw one of the greatest commanders in history as a success. “If I called myself the victor at Eylau, it was only because you chose to retreat,” Napoleon said two years later to Russian Military Attaché Colonel Aleksandr Chernyshev.

Tsar Alexander I was of a similar opinion. “It was your destiny to earn glory by defeating the one who has never been defeated,” he wrote to Bennigsen shortly after the battle. Not everyone was so charitable. General Osten-Sacken described Bennigsen’s after-action report as “extremely contradictory, [and] includes everything except the truth.”

Bennigsen’s time to bask in glory was short. When hostilities resumed, Napoleon smashed Bennigsen at the Battle of Friedland on June14. This brought the War of the Fourth Coalition to a close. Still, the ruling houses of Europe took careful note that Napoleon had been fought to a standstill for the first time at Eylau. This gave them hope, for they sensed that the Grand Armee was not invincible after all. The bloody struggle continued for eight more years, culminating at the titanic clash at Waterloo which brought the Napoleonic era to a close.