By Christopher Miskimon

Royal Engineer Robert Halliday was hungry. He had searched the town of Dunkirk, France, for food only to find nothing. As he searched a German bomb exploded nearby, blowing out his eardrums and hurling him 50 yards. Now, hungry and with little else to do, he and 50 other engineers began building a raft out of empty fuel cans and boards from truck beds. They thought they might be able to get it out to a ship; those who could not swim would sit on it while the swimmers pushed it out to sea for rescue. As they worked other soldiers sat around doing nothing. One saw a British helmet lying on the beach and quipped, “Blimey, he’s dug himself in well!”

Subaltern Anthony Irwin was on leave from the 2nd Battalion, Essex Regiment when the Battle of France began. He spent days trying to get back to his unit, searching through the chaos with one of his sergeants. He managed to find it and soon found himself in battle. Days later, he recalled being bivouacked in an orchard when a British plane was beset overhead by a half-dozen German Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters. As each fighter attacked, however, the British pilot expertly maneuvered to avoid it, to the cheers of the infantrymen.

The Germans then attacked the RAF plane simultaneously, but they had to come low to catch the descending aircraft. When they did, every Bren gun in the company opened up on the Me-109s, bringing one down in flames. The rest promptly forgot the air battle and began strafing Irwin’s troops, only to be chased off moments later by RAF Hawker Hurricanes. Within hours they dug in after relieving a gingerbread factory of its contents. Anthony Irwin would reach the beach at Dunkirk and be evacuated aboard an Isle of Man ferry, surreally being served a glass of beer by a steward who would not give it to him until they were three miles offshore—as per regulations.

By the time it was done more than 330,000 Allied soldiers were evacuated from Dunkirk to England, providing a nucleus from which the future British Army would be created. Hundreds of small boats and civilian craft were used along with naval vessels to bring them home, and many were lost. It was a time when the entire United Kingdom came together to retrieve its army, saving it from destruction.

By the time it was done more than 330,000 Allied soldiers were evacuated from Dunkirk to England, providing a nucleus from which the future British Army would be created. Hundreds of small boats and civilian craft were used along with naval vessels to bring them home, and many were lost. It was a time when the entire United Kingdom came together to retrieve its army, saving it from destruction.

The evacuation at Dunkirk in May and June 1940 is famous, and the use of civilian craft to rescue thousands of Allied soldiers is equally well known. The true details of the story are in the myriad personal tales of the operation, where privates, sergeants, and junior officers had to get through the ordeal and bring order out of chaos. That is the tale the reader gets in Dunkirk: The History Behind the Major Motion Picture (Joshua Levine, William Morrow Publishing, New York, 2017, 354 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, $16.99, softcover).

This is a companion book to the recent film Dunkirk, which has received many favorable reviews for its depiction of the event. This book also deserves favorable mention due to its detail, flowing narrative, and ground-level storytelling. The movie focuses on lower level leaders and enlisted men, and this book does the same. Dunkirk was not a great victory or even a great defeat, though it stemmed from a defeat. It is instead a story of survival, revealing how a disparate group of soldiers, sailors, and airmen came together to preserve an army that would go on to help defeat Germany within five years, fighting in North Africa and Italy along the way. Hundreds of thousands of men occupied the beaches of Dunkirk. There are far too many stories to recount in a film; this work gives the reader a deep look at some of those stories.

Since this is a book meant to accompany a film, it also contains a nicely done section where the making of that film is discussed. The film’s director is loath to use the extensive computer-generated images so many movies depend upon now, so sets, aircraft, and vehicles all had to be located and procured for use. All of the aircraft are actual flying examples or large scale remote-control models, for example. How such attention to detail is used to make a realistic war film is also worthy of attention.

We Stormed the Reichstag (Vassili Subbotin, translated by Tony Le Tissier, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, maps, photographs, $$34.95, hardcover)

We Stormed the Reichstag (Vassili Subbotin, translated by Tony Le Tissier, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, maps, photographs, $$34.95, hardcover)

Mikhail Yegorov and Meliton Kantara were just regular soldiers, scouts in the Soviet Army’s 756th Rifle Regiment. According to the author, on April 30, 1945, these two men were part of a group that stormed the Reichstag building in Berlin, Germany. They carried with them a flag that had been passed down from the 150th Division commander. The building was practically in ruin as the pair made their way to the roof, where they raised the flag; an iconic photograph of the incident is a common image of the war in Europe’s last days.

It is a glorious image and story, but it is not altogether true. Other flags were raised earlier in the building, and other men seized the Reichstag from its Nazi defenders. The author of this work was a Red Army soldier in 1941, and by 1945 he was a war correspondent accompanying the troops as they fought the last days of the war in Germany. He records some of these incidents, throwing together a fascinating narrative of what Soviet troops experienced in those days. The book reads very much as if written by a reporter of the times, which it was. The author, an expert on the Eastern Front, served in Berlin during the Cold War and it is to his credit he has brought this work to English-speaking readers, providing more source material on the Red Army in World War II.

Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler (Bruce Henderson, William Morrow Publishers, New York, 2017, 448 pp., photographs, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $28.99, hardcover)

Sons and Soldiers: The Untold Story of the Jews Who Escaped the Nazis and Returned with the U.S. Army to Fight Hitler (Bruce Henderson, William Morrow Publishers, New York, 2017, 448 pp., photographs, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $28.99, hardcover)

The Ritchie Boys were the initiators of a classified operation used by the American army against the Nazis during World War II. Named for the camp where they were trained, these German-born Jewish men managed to escape Germany before the war began, but once the conflict started their unique knowledge was needed by the Allies. The Ritchie Boys spoke fluent German; they knew the culture, the traditions, and the tiny details of life inside the Third Reich. Almost 2,000 of these men were given training in special interrogation techniques and formed into small teams. These groups were attached to every large unit in the European Theater, where they were used to gather vital intelligence from captured enemy soldiers. These Jewish soldiers did so despite the risks if they were themselves captured by the Nazis, who would almost surely execute them. Their contributions helped win the war, gathering information that saved lives in combat.

It is widely known that German-speaking soldiers were used as translators and interrogators in the American military during the war, but the story of these Jewish-American troops is almost entirely unknown in popular history today. The author interviewed surviving Ritchie Boys and pored through archival records, succeeding in creating a work that does justice to their effort and sacrifices. The book has a flowing narrative and a down-to-earth style that is very engaging.

The Allies Strike Back 1941-1943: The War in the West (James Holland, Atlantic Monthly Press, Berkeley, CA, 2017, 720 pp., maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $30.00, softcover)

The Allies Strike Back 1941-1943: The War in the West (James Holland, Atlantic Monthly Press, Berkeley, CA, 2017, 720 pp., maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $30.00, softcover)

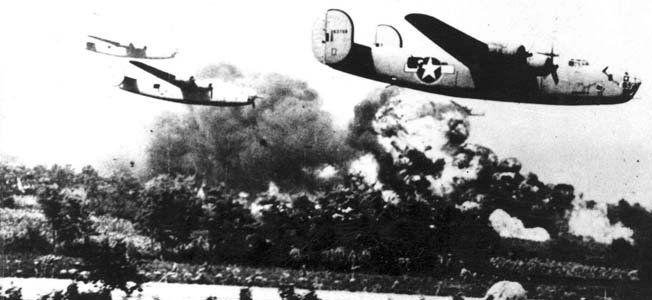

Mid-1941 was a bleak time for the Allies. It seemed Nazi Germany was victorious everywhere, from the deserts of North Africa to the North Atlantic to the vast steppes of the Soviet Union. By the end of the year the situation, while still serious, began to show signs of change. The Germans had not been defeated, but they were stopped in several places, including the gates of Moscow. The Americans had entered the war, though it would be months before their presence was felt in any real way. Within a year, General Erwin Rommel would be defeated by the British and driven back across the desert, where he would find American troops awaiting him to the west. Germany would also begin to suffer under the bomber offensive, and their second year of grand offensives against the Soviets would bog down again, this time at Stalingrad. There was much yet to be done, but the job of victory was well started.

This is an epic, sweeping work that relates the wide events of the war to each other in a compelling way while still paying attention to the experiences of the soldiers and civilians in harm’s way. The author’s grasp of detail and persuasive arguments are both compelling and interesting. This book is a good overall history of the war in Europe’s middle years.

MacArthur’s Spies: The Soldier, the Singer and the Spymaster Who Defied the Japanese in World War II (Peter Eisner, Viking Press, New York, 2017, 335 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover)

MacArthur’s Spies: The Soldier, the Singer and the Spymaster Who Defied the Japanese in World War II (Peter Eisner, Viking Press, New York, 2017, 335 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover)

On January 2, 1942, the Japanese Army occupied the Philippine capital city of Manila. They were unopposed by the Filipino-American Army, which could not hope to defend the city without risking its destruction and its own ability to defend the rest of the nation. Within a few months that army would be defeated and its survivors marched off into captivity, brutality, and death. Not everyone gave up, however. Colonel John Boone led a group of guerrilla fighters from hiding, infiltrating Manila and striking the Japanese where they could. “Chick” Parsons was a businessman and reserve naval intelligence officer who managed to escape disguised as a Panamanian diplomat and returned to service as an overseer and coordinator for the resistance operations in the Philippines. Claire Phillips sang at a Manila nightclub where she and the other employees gathered intelligence and smuggled food and supplies to both the guerrillas and prisoners.

This account of resistance to the Japanese occupation is filled with the details of harrowing risks, daring gambles, and hard-won successes. The prose is smooth and engaging; at times the book reads almost like a spy novel. The author delves into the controversies surrounding Claire Phillips like a detective sorting out a case. The result is a work that vividly recounts the real-life adventures of a unique group of people struggling to help win a war and survive the experience.

Shadow Over the Atlantic: The Luftwaffe and the U-Boats 1943-45 (Robert Forsyth, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2017, 312 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $30.00, hardcover)

Shadow Over the Atlantic: The Luftwaffe and the U-Boats 1943-45 (Robert Forsyth, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2017, 312 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $30.00, hardcover)

By the autumn of 1943, the Nazi U-boat service was past its heyday. Allied advances in technology and tactics were forcing enemy submarines into a defensive fight. German Admiral Karl Dönitz needed something to give his sailors an advantage and looked to one of the weapons the Allies were using so effectively against him: the airplane. He asked the Luftwaffe to provide a group that could scout for convoys and shadow them so the submarines could be directed in for the attack. This unit, aptly nicknamed “Atlantik,” flew the large four-engine Junkers Ju-90. This aircraft carried radar and could range thousands of miles from bases in western France. Though their efforts proved futile in changing the course of the war, the aircrews worked endlessly to provide the naval high command with the intelligence they needed to maximize the effectiveness of their U-boats.

The Battle of the Atlantic is usually told from the point of view of submariners and their opponents. This work is significant in telling the story from the point of view of the German maritime reconnaissance flyers, whose story has never before been told outside official records. Their history through to the war’s end is thoroughly covered, appealing to both naval and aviation enthusiasts alike.

Their Backs Against the Sea: The Battle of Saipan and the Largest Banzai Attack of World War II (Bill Sloan, Da Capo Press, Boston, 2017, 304 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $27.00, hardcover)

Their Backs Against the Sea: The Battle of Saipan and the Largest Banzai Attack of World War II (Bill Sloan, Da Capo Press, Boston, 2017, 304 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $27.00, hardcover)

Lieutenant Colonel William O’Brien stayed with his men as an enormous Japanese banzai attack overwhelmed his battalion. He refused to leave while even one of his soldiers was still on the line. He took up a position at a water cistern and fired his carbine at the hundreds of charging enemy troops. Ahead of him two Japanese were moving among wounded Americans, slashing them with their swords. O’Brien cut them down with his carbine and reloaded. Soon he ran out of carbine ammunition and switched to a pair of pistols. When those were empty he grabbed a rifle and even manned a .50-caliber machine gun. When that too was empty he took up an enemy sword and leaped at the Japanese, shouting “Don’t give them a damn inch!” He slashed away at them until he was cut down. When his body was recovered the next day, 30 enemy soldiers were found around him.

The Battle of Saipan was a brutal three-week struggle, with the attacking Americans fighting a well-entrenched and determined enemy. The battle culminated in a desperate banzai charge by 4,000 starving troops that lasted four hours. This book is a detailed, in-depth account of that engagement, giving the reader a ground-level view of the battle, revealing what the survivors experienced.

Patton’s Way: A Radical Theory of War (James Kelly Morningstar, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2017, 280 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

Patton’s Way: A Radical Theory of War (James Kelly Morningstar, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2017, 280 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

General George Patton was a complex man, and history has treated him in an equally complex way. Popular history idolizes him for his effectiveness while glossing over his flaws. Many scholarly assessments are more critical of his methods and shortcomings, however. The author of this new work argues that Patton’s techniques were not understood by his peers and didn’t conform to accepted doctrine. These techniques included targeting enemy morale through shock attacks, being flexible in the command and control of his units, and using multiple intelligence assets to identify German weaknesses. The book is full of real-world examples of Patton’s operations, showing how he achieved his victories in Tunisia, Sicily, and France after the Normandy breakout. Many books have been written about Patton; this one stands out for its thorough analysis and effective arguments.

New and Noteworthy

Bader’s Last Fight: An In-Depth Investigation of a Great WWII Mystery (Andy Saunders, Pen and Sword, 2017, $29.95, softcover) Douglas Bader was a fighter pilot shot down in 1941. The author explores the possibility he was downed by friendly fire.

Bader’s Last Fight: An In-Depth Investigation of a Great WWII Mystery (Andy Saunders, Pen and Sword, 2017, $29.95, softcover) Douglas Bader was a fighter pilot shot down in 1941. The author explores the possibility he was downed by friendly fire.

Divided on D-Day: How Conflicts and Rivalries Jeopardized the Allied Victory at Normandy (Edward E. Gordon and David Ramsay, Prometheus Books, 2017, $26.00, hardcover) This book highlights the egos, national rivalries, and abilities of the high-ranking leaders who planned Operation Overlord. The authors argue these disagreements lengthened the war.

Letters from the Greatest Generation: Writing Home in WWII (Edited by Howard Peckham and Shirley Snyder, Indiana University Press, 2017, $25.00, softcover) This is a collection of letters written by men and women serving overseas during the war. It is intended as a tribute to their service and experience.

The History of the Panzerwaffe Volume 2: 1942-45 (Thomas Anderson, Osprey Publishing, 2017, $40.00, hardcover) The Panzer force reached the height of its power in 1942 but declined afterward. This volume chronicles that period.

Hitler’s Soldiers: The German Army in the Third Reich (Ben H. Shepherd, Yale University Press, 2017, $35.00, hardcover) This is a new work examining the relationship between the German Army and the Nazi state. It relates that the Nazis could not have done what they did without the Army’s complicity.

Blitzkrieg, Myth, Reality and Hitler’s Lightning War: France 1940 (Lloyd Clark, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2017, $27.00, hardcover) This is an unvarnished look at the French Campaign. The author maintains it was not the easy victory portrayed in popular history.

Blitzkrieg, Myth, Reality and Hitler’s Lightning War: France 1940 (Lloyd Clark, Atlantic Monthly Press, 2017, $27.00, hardcover) This is an unvarnished look at the French Campaign. The author maintains it was not the easy victory portrayed in popular history.

The Accidental President: Harry S. Truman and the Four Months That Changed the World (A.J. Baime, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017, $30.00, hardcover) Harry Truman took on Germany, Japan, and Stalin and ordered the dropping of the atomic bomb in his first four months in office. Just as important, he had to deal with the aftermath and peace.

Selling Hitler: Propaganda and the Nazi Brand (Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, Hurst and Company, 2017, $34.95, hardcover) This examination of the Nazi propaganda machine demonstrates how it became not just a tool but a purpose of the state.

Tanks of the Second World War (Thomas Anderson, Pen and Sword, 2017, $39.95, hardcover) This reference work covers all the main tank models of the war. It is well illustrated and full of technical tables.

The Normandy Battlefields: Bocage and Breakout (Simon Forty, Leo Marriott and George Forty, Casemate Books, 2017, $34.95, hardcover) This coffee table book takes an in-depth look at the landings and subsequent fighting. It has many before and after photos.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments