By Pat McTaggart

Colonel General Walter Model was a rising star in the German ArFmy in early 1943. The son of a music teacher, Model was born on January 24, 1891, in Genthin, Saxony-Anhalt. In 1909, he joined the Kaiser’s army as an officer candidate, but the harsh training almost made him quit. He was dissuaded by an uncle and went on to pursue a military career.

During World War I he served on the Western Front as a battalion adjutant. Severely wounded near Arras in May 1915, he returned to the front and took part in the battles of Verdun and in areas around the Vosges and Champagne sectors. He finished the war as a captain.

Model remained in the postwar German Army and made his way from company to battalion commander. Period photographs show him as a caricature of the archetypal German officer, complete with closely cropped hair and a monocle. By 1938, he was a brigadier general and chief of staff of the IV Army Corps.

The pro-Nazi Model rose to the rank of major general and served as chief of staff of the 17th Army during the French Campaign in 1940. In November of that year, he was given command of the 3rd Panzer Division. Under Model’s leadership the division performed admirably during the opening phase of Operation Barbarossa and took part in the battles at the Kiev and Minsk pockets.

On October 1, 1941, Model was promoted to general of panzer troops and was given command of the XLI Panzer Corps. For his successes with the 3rd Panzer Division, Model had been awarded the Knight’s Cross in July. The award of the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross followed in February 1942, for his handling of the XLI Panzer Corps.

Model showed a defensive flair during the opening of the Soviet winter offensive in December 1941. When the German 9th Army was nearly surrounded west of Moscow, Model took command of the unit on January 15, 1942. Although the army was forced to retreat, it did not lose its cohesiveness and was able to grind down the Russians as Model anchored his defenses in the Rzhev sector.

Promoted to colonel general on February 1, Model kept his 9th Army in stout defensive positions at Rzhev for the rest of 1942. On September 1, he was severely wounded by an enemy bullet, which cut his pulmonary artery and sent him to the hospital until January 1943. When he resumed command, he was ordered to prepare a withdrawal from the Rzhev salient. In the spring, he conducted a masterful retreat, thoroughly fooling the Soviets and making the 9th Army ready for the next German offensive, which was due to take place in the summer.

The plan was called Operation Zitadelle (Citadel). Following the capitulation of the 6th Army at Stalingrad and the loss of vast tracts of land during the Soviet offensive that followed, Hitler was anxious to regain his prestige and “to get back in the summer what was lost during the winter.”

At a February conference among Hitler, the chief of staffs of the Armed Forces and the Army (General Alfred Jodl and General Kurt Zeitzler), and the commanders of Army Groups Center and South (Field Marshals Günther von Kluge and Erich von Manstein), it was decided that the only way to stabilize the Eastern Front was through offensive operations. One of the areas that caught everyone’s eye was the Soviet salient around the city of Kursk, which was approximately 200 kilometers wide and protruded about 100 kilometers into the German line.

“The appreciable Soviet forces inside the salient would be cut off if our attack was successful, and provided that we launched it early enough we could hope to catch them in a state of unpreparedness,” Manstein wrote in his memoirs. “In particular, the enemy could have to commit the armored units which had been so severely battered toward the end of the winter campaign, thereby giving us a chance to punish them wholesale.”

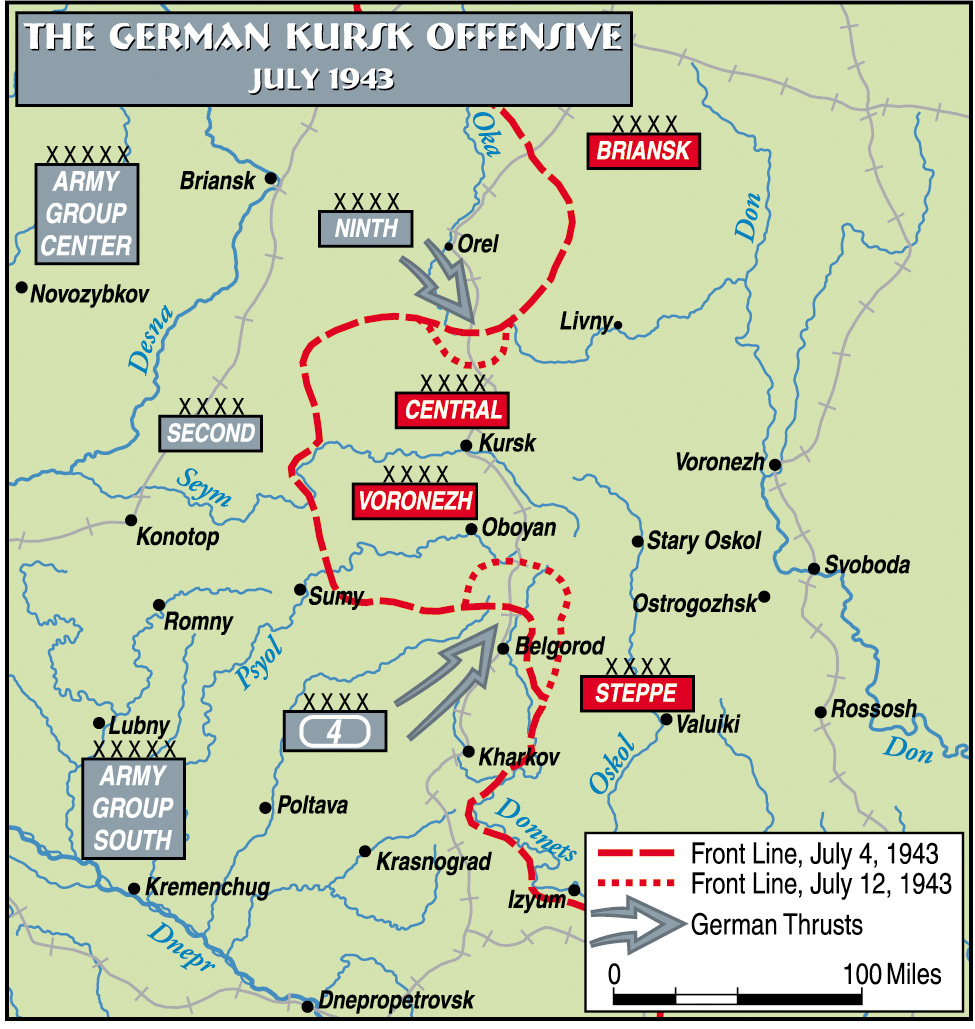

The eventual operation envisioned an attack by two of Manstein’s armies (4th Panzer and Army Detachment Kempf) in the south and Model’s 9th Army, from Kluge’s Army Group Center, in the north. When the pincers of the attacking forces met and the Soviets inside the salient were trapped, more German units would attack from the west and destroy the enemy. The resulting victory would not only annihilate significant enemy troops and material, it would also shorten the front by 240 kilometers, which would provide the Germans with a reserve force to counter any Soviet threats in other areas.

Zitadelle was slated to begin during the first half of May. By then the ground would be sufficiently dried out from the muddy season. It was also expected that Russian units would still be refitting and rebuilding from the losses they had suffered during the winter.

Against the advice of Manstein, Hitler decided to postpone the attack until June, when he hoped new panzer models would be available for his armored units. The attack was again postponed by the Führer when the new panzers did not arrive on time.

Manstein felt the chances for victory slipping away because of the delays. The respite had given the Soviets time to bring their units, especially their armor, up to strength for the most part. The German buildup in the area could not be hidden, and new Russian positions were popping up every day. Soviet reinforcements were also pouring into the area to serve as reserves for the armies posted inside the salient.

The Russians, now well aware of the impending attack, took the time to lay extensive minefields in front of their strongly fortified defensive lines within the salient. Tens of thousands of civilians were used to dig antitank ditches, and supply and ammunition dumps were being filled to the brim. In a 1971 letter to the author Manstein tersely replied to a question concerning the possible success for Zitadelle. He wrote: “If we had begun the offensive as first planned, we would have achieved the [desired] breakthrough.”

Manstein was not the only general who had doubts about the operation. Although the field marshal kept his thoughts to himself at a May 3 conference in Munich, Walter Model had no such qualms. His superior, Kluge, strongly supported Zeitzler’s plan for the north-south pincer attack. Bypassing the chain of command, Model met with Hitler the day before the conference took place.

Model laid out his case for either revising or cancelling the attack altogether, showing Hitler aerial reconnaissance photos of the growing Russian defensive positions. He said that he needed at least two more panzer divisions and thousands more infantrymen to even have a chance of breaking the Soviet lines, which he doubted he could, given the extensive Russian defenses.

At the May 3 conference, Hitler presented Model’s objections, much to Kluge’s irritation. Kluge pointed out that the delay would give time for the new Panther, Tiger, and Ferdinand tanks to reach the front and that their appearance in the battle would thoroughly outweigh any improvements the Russians could make in their defenses. His argument seemed to influence Hitler.

General Heinz Guderian, the Inspector of Panzer Troops, was never one to keep his opinions to himself. He was against the whole thing. He cited design problems with the new panzers that still had to be worked out. He also wanted to use the tanks to build up an armored reserve to fend off the expected Allied invasion in the West, which he thought would take place within the next year.

The back and forth continued with little being settled. In the end, preparations for Zitadelle continued, almost as if they had a life of their own. Hitler waited for the new panzers, both sides continued to send more men to the front, and the Russians continued to build stronger defense lines. The date for the attack was finally set for July 5. As that date approached, Model continued to pour over reconnaissance photos with his staff. His objective was to smash through the minefields and the three Soviet defensive belts facing him and then head southeast toward the village of Olkhovatka, dozens of kilometers from the jump-off point.

To accomplish this daunting task, Model had five German and one Hungarian corps under his command. There were 16 German and three Hungarian infantry divisions along with one panzergrenadier and six panzer divisions, six Sturmgeschütze Abteilungen (Stug. Abt.—assault gun detachments), a panzer brigade, a schwere Panzer Abteilung (schw. Pz. Abt.—heavy tank detachment) and a schwere Panzerjäger regiment (schw. Pz. Jäg.—heavy antitank).

In all, according to historian David Glantz, Model commanded a force of about 335,000 men, 590 panzers, and 424 assault guns. He would be supported by General Robert Ritter von Greim’s 4th Air Fleet. Greim was charged with disrupting enemy movement and command and control, smashing enemy defensive positions, and supporting the ground attack.

For a panzer general, Model’s plan of attack was reserved. Instead of an assault using his panzer divisions to open breaches in the enemy line, he planned to use his infantry to batter their way through the defenses. The panzer units that were committed to the initial attack would be closely supported by the infantry, which would fend off Soviet infantry and attack antitank defenses. Once the three Soviet defensive lines were breached, Model would order his panzer reserve to exploit the success and move into the open area behind the Russian positions.

Besides the panzers, the infantry would be supported by the assault gun detachments and the newly formed schw. Pz. Jäg. Rgt. 656, commanded by Lt. Col. Ernst Freiherr von Jungenfeld. The 656th was composed of schw. Pz. Jäg. Abts. 653 and 654 with a total of 89 new Ferdinand heavy assault guns. The Ferdinands had been completed by the end of May and had just arrived before the offensive was to being.

Their 88mm guns would make them excellent tank destroyers, but they lacked any secondary armament, making them vulnerable to enemy infantry attacks. In Captain Karl-Heinz Noak’s Abt. 654 some of the crews armed themselves with MG-34 machine guns, which they hoped they could fire through the open gun breech in case they were attacked in close combat.

The third detachment in von Jungenfeld’s regiment was Major Bruno Kahl’s Sturmpanzer Abteilung 216. Kahl had 45 Sturmpanzer IV “Grizzly Bear” assault guns at his disposal. They sported a 150mm gun for infantry support and, unlike the Ferdinands, had two machine guns for defense. The Grizzlies were also fast tracked into production so that they could participate in Zitadelle.

Model also had two companies of the vaunted Tiger tanks, which had also been rushed to the front. Under the command of Major Bernhard Sauvant, the two companies of schw. Pz. Abt. 505 would be attached to Maj. Gen. Horst Grossmann’s 6th Infantry Division for the beginning of the attack.

Facing Model was General Konstantin Rokossovskii’s Central Front. Rokossovskii had one tank and five infantry armies, as well as several units directly subordinated to the front for a total force of about 711,000 men and 1,785 tanks and self-propelled guns.

As previously stated, the Soviet defenses consisted of three heavily fortified lines. For months Red Army engineers had sown thousands upon thousands of mines in the area. The minefields were designed to funnel German armor into kill zones. Antitank, or PAK, fronts had been positioned in the killing zones. Numerous antitank guns, under the command of one officer, would fire at one designated tank until it was disabled or destroyed before moving on to the next one.

The Soviet infantry manning the lines had integrated antitank elements armed with the PTRS-41 “Siminov” antitank rifle. A bulky 46-pound weapon, the Siminov fired a 14.5x114mm armor-piercing round that could penetrate 40mm of armor at 100 meters. At close range it could be a deadly weapon, even against the heavy German tanks that were being introduced to the battlefield.

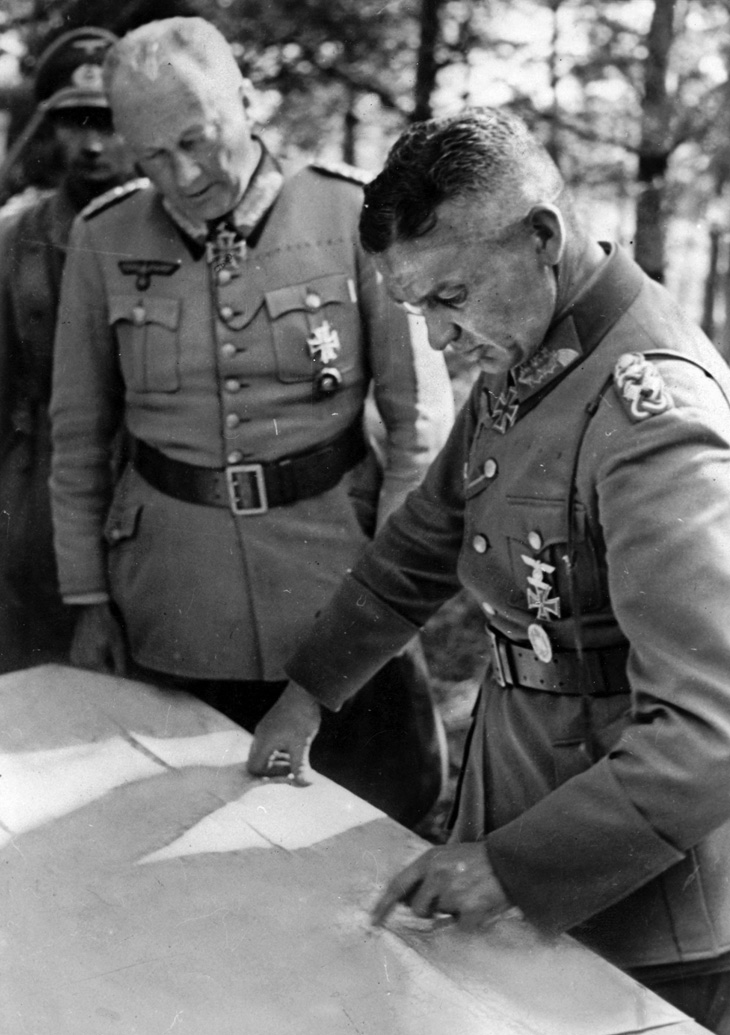

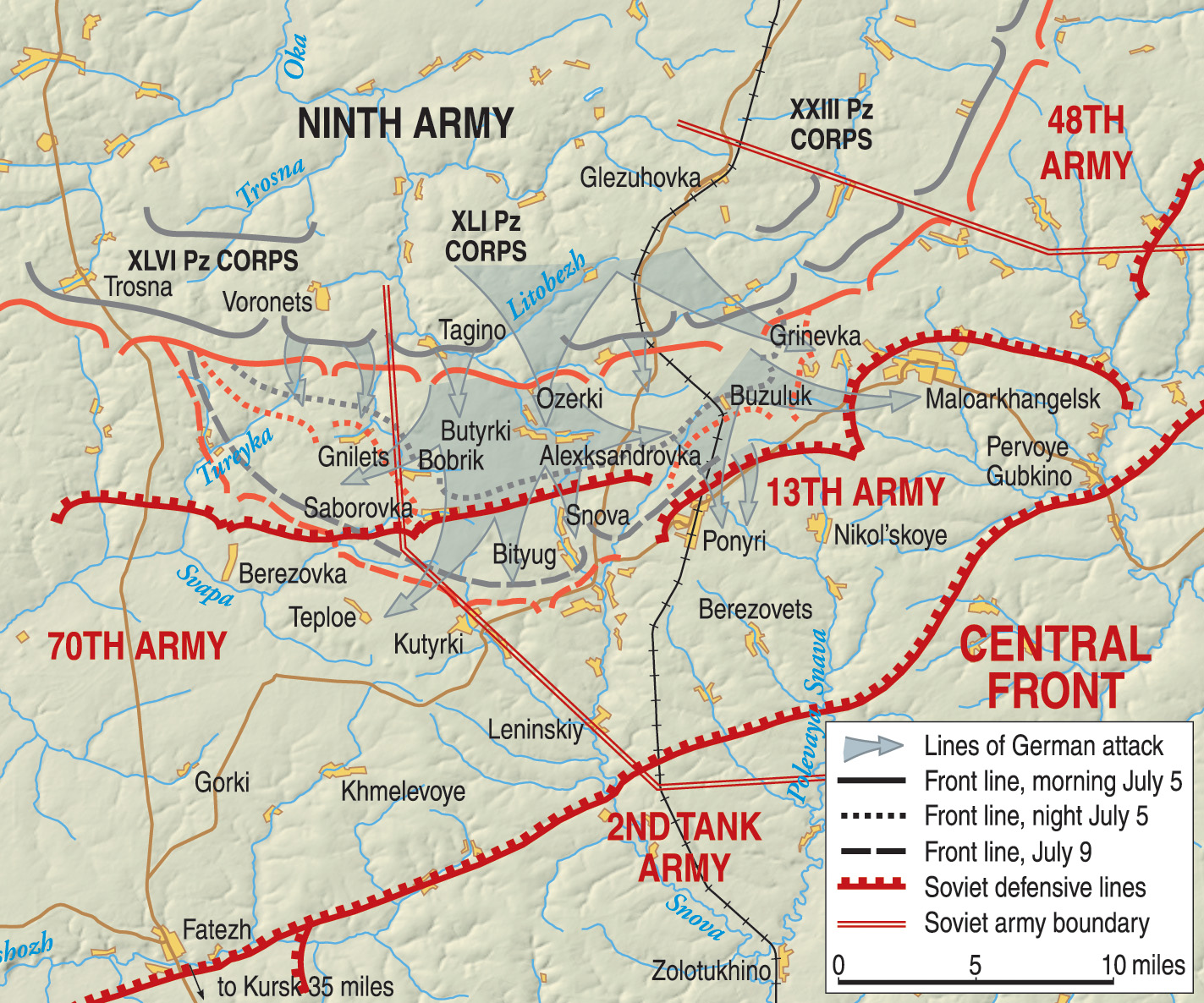

As the hour for the attack neared, Model, his chief of staff, Colonel Harald Freiherr von Elverfeldt, and his chief of operations, Colonel Johannes Hölz, went over the final plans for the assault. On his right flank, General Johannes Freissner’s XXIII Army Corps (353rd, 216th, 78th, and 36th Infantry Divisions and Stug. Abts. 185 and 189) would face off against Lt. Gen. Prokofii Romanenko’s 48th Army.

The main effort would take place in the center of the line with General Josef Harpe’s XLI Panzer Corps (86th and 296th Infantry Divisions, 18th Panzer Division, schw. Pz. Jäg. Abt 656, and Stug. Abts. 177, 244, and 909) hitting Lt. Gen. Nikolai Pukhov’s 13th Army. To Harpe’s right, General Joachim Lemelsen’s XLVII Panzer Corps (6th Infantry Division, 20th, 9th, and 2nd Panzer Divisions, Stug. Abts. 245 and 904, and Kahl’s 216th Grizzlies) would join in the attack on Pukhov’s line. In Lt. Gen. Ivan Galinin’s 70th Army sector, General Hans Zorn’s XLVI Panzer Corps (31st, 7th, 258th, and 102nd Infantry Divisions) was tasked with opening and widening a breach between the 70th and 13th Armies.

Through the interrogation of German prisoners and accounts from a few German deserters, Rokossovskii knew exactly when Model would come. He therefore ordered his artillery to hit possible German assembly points at 0220 on the morning of July 5, with varied results. Some previously plotted German positions were pulverized, but many of the shells fell on vacant ground.

The bombardment did manage to disrupt Model’s opening moves. The attack was postponed for 21/2 hours while units sorted themselves out. Even then, some of the initial attacks were uncoordinated.

At 0430 the Germans opened up with their own artillery, and shells rained down on the forward Soviet line as the German infantry prepared to advance. Freissner attacked first at around 0530. His job was to divert Soviet attention from the main axis of advance farther west. With three infantry divisions he struck the boundary between the 13th and 48th Armies with the objective of taking the village of Maloarkhangelsk, about 8 kilometers behind the Russian line.

The Germans ran into a buzzsaw as the soldiers of the 148th, 8th and 16th Rifle Divisions open up a murderous fire that halted Freissner’s men almost as soon as the attack started. By the end of the day the Germans had advanced only about 1½ kilometers, even with the help of Stuka dive bomber support and the support of the corps’ 72 assault guns.

Harpe and Lemelsen fared somewhat better. Brig. Gen. Mortimer von Kessel’s 20th Panzer Division and Maj. Gen. Horst Grossmann’s 6th Infantry Division overcame heavy resistance from the 331st Rifle Regiment of Colonel V.N. Dzhandzhgava’s 15th Rifle Division and took the village of Bobrik about seven kilometers behind the first defensive line. The Russians had numerous positions in the vast cornfields in the area. First Lieutenant Hans-Werner Deppe, commander of the 3rd Company of Grenadier Regiment (GR) 58/6 I.D., was advancing through one such field. When he came under heavy fire from artillery and an entrenched Soviet rifle company, he ordered his men to engage the enemy in close combat.

Although wounded in the shoulder by grenade fragments, Deppe urged his men forward. Supported by an assault gun, Deppe led his men into the enemy positions. He was wounded again in the arm but refused treatment until the Russian positions were cleared. When it was over about 150 of the enemy lay dead and 20 more were taken prisoner. His men had also destroyed two 37mm antitank guns, a heavy machine gun, and seven vehicles. Loss of blood finally forced Deppe to go to an aid station. Deppe was awarded the Knight’s Cross five weeks later for his actions.

Grossman’s infantry and Kessel’s panzers had broken Dzhandzhgava’s defenses and forced the 15th to retreat, but just south of Bobrik they ran into the second Soviet defensive belt on the heights beyond the village, manned by Maj. Gen. Dmitrii Onuprienko’s 6th Guards Rifle Division and Maj. Gen. Mikhail Enshin’s 307th Rifle Division, which stopped the Germans cold.

Farther east, Grossmann’s troops had also taken the village of Butyrki about four kilometers inside the Russian line. Along the way, the 1st and 2nd Companies of Major Sauvant’s schw. Pz. Abt. 505 annihilated a defensive screen of Russian antitank guns and T-34 medium tanks with accurate fire from their Tigers’ 88mm guns. During the action the commander of the 1st Company, Captain Riedesel, was killed.

The pace at which Sauvant’s Tigers advanced came as a surprise to Model, as he had expected that the first defensive belt would be harder to crack. Therefore, he was still holding most of his armor in the rear as a reserve instead of acting decisively and committing them to enlarge the penetration.

Major General Grossmann later wrote, “Far in front of the division was a hill massif on which the movements of the Russians could be identified. If the (reserve) armored divisions had rolled forward at that point, then we might have reached the objective of Kursk. The enemy had been completely surprised and was still weak. Valuable time was lost, which the enemy used to commit his reserves.”

To the left of Lemelsen, Harpe’s XLI Panzer Corps was also partially successful. With Brig. Gen. Wolfgang von Kluge’s 292nd Infantry Division on the corps’ right flank and Maj. Gen. Helmut Weidling’s 86th Infantry Division on the left, and supported by elements of Brig. Gen. Wilhelm von Schlieben’s 18th Panzer Division, the Germans tore into the positions of Maj. Gen. Aleksandr Barinov’s 81st Rifle Division. Weidling’s 86th also had some heavy backup in the form of Jungenfeld’s schw. Pz. Jäg. Rgt. 656.

The initial attack of the 86th got off to a poor start. Some of Jungenfeld’s Ferdinands stumbled into an unmarked German minefield, causing significant casualties. Of the 44 Ferdinands that had participated in the initial attacks, almost one-third were lost before they were clear of their own mines, but many were recoverable and would be back in action. Others ran over Soviet mines that the German engineers had missed. The engineers, working under intense Russian artillery and small arms fire to clear the minefields, also suffered heavy casualties.

When they were finally able to properly deploy, the Ferdinands savaged the Soviet infantry that occupied the first trenchline. Barinov’s 410th and 467th Rifle Regiments were shattered by Noack’s Abt. 654. During the attack, Noack’s Ferdinand was disabled. Climbing down from the vehicle, he was critically wounded by mortar fire and had to be evacuated. Captain Rolf Henning, commander of the 3rd Company, took command of the Abteilung.

In response to the German attack, Pukhov sent Colonel Aleksii Peruvshin’s 129th Tank Brigade and the 1442nd Artillery Regiment to help Barinov’s division. They were able to stop the Germans four times before being forced to withdraw to prevent encirclement. By the end of the day, the 86th had taken the village of Buzuluk and had formed a line about two kilometers south of the village to a point two kilometers southwest of Semenovka.

Kluge’s 292nd failed to take its first day’s objective of Aleksandrovka, which was still about 1,300 meters away as night fell. It did have some success east of the village, but enemy counterattacks slowed movement and caused many casualties. The first day’s operation cost the division 84 dead, 329 wounded, and four captured.

Just to the right of the 292nd, the 18th Panzer committed its PGR 101 to take Soviet positions in a wooded area dubbed the “Schwarzwald (Black Forest).” Lt. Col. Fleischauer’s regiment had 923 men and was supported by a company of Colonel Friedrich von Seidlitz’s PGR 52, an engineer company, and a platoon of antitank weapons.

As the regiment approached the village of Ozerki, located north of the forest, it came under heavy mortar and small-arms fire. Casualties mounted as the Soviets continued to rake the Germans, forcing Fleischauer’s men to dig in. Schlieben was forced to commit more of the 18th Panzer earlier than he wanted to because of the fierce fighting, and the rest of Seidlitz’s regiment was soon moved forward. By 1500, the 101st had captured Ozerki, but it could not continue to advance into the forest. The regiment had lost 50 dead, 16 missing, and 196 wounded during the attack. A total of five enemy rifles and one antitank gun was all the Germans had captured for their effort.

Model seemed content with the first day’s results. He had expected a hard fight, and the Soviets did not disappoint him. In some areas his men had been more than successful, while in others they had failed to take their objectives. Plans were worked out to take the Schwarzwald on the 6th, but they proved unnecessary because the surviving members of the 676th Rifle Regiment pulled out of the forest during the night due to threats on both flanks.

That Model failed to commit his armored reserves did not seem that important to him. He would do that the next day, but by then it would be too late to really make a difference. He had lost 20 percent of his armor due to mines, enemy action, or mechanical failure, many of which would be recovered. By failing to let his reserves exploit the gains that had been made, especially in the 6th Infantry’s sector, he allowed Rokossovskii to bring up his own reserves. Even as the Germans dug in for the evening, Rokossovskii was already planning a counterattack for the next day.

The Soviet general planned to hit both Lemelsen and Harpe using Lt. Gen. Andrei Bondarev’s 17th Guards Rifle Corps (6th, 70th, and 75th Guards Rifle Divisions) and Maj. Gen. Ivan Afonin’s 18th Guards Rifle Corps (2nd, 3rd, and 4th Guards Airborne Divisions). They were to be supported by Maj. Gen. Maksim Sinenko’s 3rd Tank Corps (50th, 51st, and 103rd Tank Brigades and 57th Motorized Rifle Regiment) and Maj. Gen. Vasilii Grigorev’s 16th Tank Corps (107th, 109th, and 164th Tank Brigades and 15th Motorized Rifle Brigade), a total of 224 tanks from Lt. Gen. Alekseii Rodin’s 2nd Tank Army.

Major General Semen Bogdanov’s 9th Tank Corps (23rd, 95th, and 108th Tank Brigades and 8th Motorized Rifle Regiment) with its 168 tanks was ordered forward from the Front reserve to exploit any breakthrough. To strengthen the right flank of Galanin’s 70th Army, Maj. Gen. Ivan Vasilev’s 19th Tank Corps (79th, 101st, and 202nd Tank Brigades and 26th Motorized Rifle Brigade) with its 168 tanks was also released from the Front reserve.

Rokossovskii may have been too impatient. Although the Germans had suffered significant armor losses, they were still a powerful force. It may have been better to let them try to batter their way through the PAK fronts, further weakening them, before committing his own tank forces.

At any rate, the attack did not go exactly as planned. Finding paths through the Soviet defensive belts was difficult at night, and neither Vasilev nor Sinenko was in position by the time the attack was to begin. The only ones that were fully prepared for the attack were Bondarev and Grigorev.

On the German side, Model expected to continue his own attack with Kluge’s 292nd driving south-southeast, cutting the rail line at Ponyri Station, and then driving another two kilometers before stopping for the day—a total penetration of about nine kilometers. Kluge would be supported by Weidling’s 86th on the left and by von Schleieben’s 18th Panzer and Grossmann’s 6th Infantry on the right. Model was also ready to commit part of his armored reserves, Maj. Gen. Walter Scheller’s 9th Panzer and Maj. Gen. Vollrath Lübbe’s 2nd Panzer Divisions, to exploit any success. Therefore, both sides were gearing up for an attack in the same sector and with added reinforcements. It would be a bloody day.

At 0350 on July 6, the one mortar and two artillery divisions of Maj. Gen. Nikolai Ignatov’s 4th Artillery Preparation Corps opened up on the German lines while the 17th Guards Rifle Corps and 16th Tank Corps moved forward. The 18th Guards Rifle Corps also began attacking. Vasilev’s 19th Tank Corps, arriving piecemeal on the scene, would join in the general assault once it was underway, while Sinenko’s 3rd Tank Corps was to occupy a defensive line south of Ponyri Station.

The Germans reacted quickly, and Model threw the 2nd and 9th Panzer Divisions into the fray. Major Sauvant’s Tiger detachment was attached to the 2nd Panzer. In the early morning light, Sauvant saw more than 100 enemy tanks approaching. More tanks from both sides were arriving on the battlefield, and as the sun rose higher there were almost 1,000 armored vehicles in action.

A heavy overcast prevented intense air activity, so it was up to the tank crews to fend for themselves. Sauvant’s Tigers destroyed several enemy tanks and were able to take the village of Saburovka. As reinforcements arrived, Sauvant was ordered to intercept Lt. Col. Nikolai Teliakov’s 107th Tank Brigade, which was headed toward Butyrki. Deploying his panzers in ambush positions, Sauvant waited for the Russians to appear.

As Teliakov’s tanks came into view, Sauvant gave the order to fire. Within minutes the deadly 88s had destroyed 48 of the 50 tanks in Teliakov’s brigade. On Teliakov’s left flank, Colonel N.V. Kopylov’s 164th Tank Brigade lost an additional 23 tanks. Sauvant’s Tigers had shown their claws, but the real battle had only just begun.

As the Soviets made a fighting retreat in Lemelsen’s sector, Harpe’s three divisions were trying to sever contact between the 13th and 48th Armies east of Ponyri. Kluge’s 292nd ran into heavy fire from the forward regiments of Maj. Gen. Afanasii Slyshkin’s 29th Rifle Corps. To Kluge’s left the 18th Panzer made painfully slow progress against the 57th Motorized Rifle Brigade and Colonel Georgii Maksimov’s 103rd Tank Brigade. It was also held up by the Ochka River, which had to be bridged before it could be crossed. Engineers spent the remainder of the day working on a 24-ton bridge that could handle the panzers, but it was not ready until 0200 on July 7.

Model’s insertion of the 9th Panzer to the east of the 6th Infantry bore little fruit. By the end of the day, the vanguard of the division under Colonel Ludwig Schmahk had clawed its way through Soviet minefields and antitank positions and had formed a bridgehead across the Snova River, where the second Soviet defensive belt halted further progress about 1.5 kilometers southwest of Ponyri.

On the far left of Harpe’s corps, Colonel Matrtin Bieber, commander of the 86th Division’s GR 184, had lost communications with divisional headquarters either from enemy artillery fire cutting the lines or by Soviet soldiers still trapped behind the lines. With his regiment taking substantial casualties, Bieber commandeered five Ferdinands and took 25 of his grenadiers and led them forward. Fire from the Ferdinands scattered several Soviet infantry companies that were in defensive positions.

Bieber managed to reach Hill 256.5, about two kilometers northeast of the 1 Maja (1 May) collective farm and about four kilometers from the Ponyri railway station. With the commanding height under his control, he formed a defensive position with his small force. Communications were restored during his advance, and reserves were sent to assist him. They finally arrived after the Soviets had made several attempts to retake the hill. Upon their arrival, Bieber ordered his men to strengthen the position as night fell.

Although the Russians had been battered, they had foiled Model’s original plan for the time being. Pukhov had managed to pull his forces back into a defensive line curving from the northeast to the southwest of Ponyri, with Enshin’s 307th Rifle Division holding a line about a kilometer outside the village. To the southwest, Onuprienko’s 6th Guards moved into strong positions while letting the shattered 15th Rifle Division pass through its lines. Maj. Gen. Vasilii Goroshnii’s 75th Guards Rifle Division was on Onuprienko’s left flank.

As Pukhov’s forces were coalescing around Ponyri, Model was issuing orders to continue the attack the following day. Although he planned to widen his front, he would concentrate his main effort in the Ponyri sector. For some reason, the rather insignificant railway station had become a fixation for him, and he was determined to take it.

Rokossovskii recognized the Germans’ attraction for Ponyri and deftly started to move some units from the 60th and 65th Armies, whose sectors had seen relatively little fighting, to reinforce Pukhov. Weather reports indicated that the 7th would be clear, and Rokossovskii ordered Lt. Gen. Sergei Rudenko’s 16th Air Army to make a maximum effort against the Luftwaffe. To counter the German panzers, Colonel N.P. Sazanov’s 13th Antitank Artillery Brigade, consisting of 2,045 men and 40 76.2mm antitank guns, was ordered from the Front reserve to Ponyri. Colonel Nikolai Vasilevich Petrushin’s 129th Tank Brigade was held in reserve behind Ponyri, while the 27th Guards Separate Tank Regiment set up positions near Hill 256.9, about 1.5 kilometers south of Ponyri. Another two artillery regiments were also sent to support the forces around the village.

Model’s objectives were somewhat more modest than the previous day’s. Kluge’s 292nd was to take Ponyri and continue on to form a line a kilometer south of the village. Colonel Hans Hahne’s GR 507 would first take the northern part of Ponyri, while Colonel Georg Zierhold’s GR 508 would take the southern part. The 18th Panzer was ordered to take over 9th Panzer’s bridgehead on the Snova River. Once that was done, the 9th would attack Soviet forces entrenched in a forested area about five kilometers east of Ponyri known as the “Birnenwald (Pear Forest).” Northeast of Ponyri, Weidling’s 86th Infantry was ordered to support the attack and retake Hill 253.5, which had been reoccupied by Soviet forces during the night.

West of Ponyri the 20th Panzer and 2nd Panzer, along with Maj. Gen. Friedrich Hossbach’s 31st and Maj. Gen. Fritz-Georg von Rappard’s 102nd Infantry Divisions, were to attack the junction between the 13th and 70th Armies. Model also planned to release Maj. Gen. Dietrich von Saucken’s 4th Panzer Division from the 9th Army reserve and send it to support the attack.

Once again Soviet artillery fire blasted German positions before Model’s forces moved out. Funneling more reinforcements into Ponyri’s flanks, Rokossovskii ordered his commanders to mount strong counterattacks at any point where the Germans threatened to break through.

At 0500 on the 7th, the 9th Panzer moved against the Soviet defenses in the dense cornfields surrounding the Birnenwald. The fighting in the area was brutal with the Soviets laying ambush after ambush before pulling back to new defenses. Red Air Force and Luftwaffe pilots dueled for control of the air, preventing either side from giving supporting fire to ground forces.

Meanwhile, the 18th Panzer was once again painfully slow in moving forward. Leading units of Colonel Friedrich von Seidlitz’s GR 52 did not begin to relieve Combat Group Schmahl until 1500, and it took more than an hour after that for Schmahl to begin moving southeast toward Bityug. South of the village he was able to establish another bridgehead across the Snova, where he ran into strong resistance from the 6th Guards. Schmahl was later joined by Combat Group Mummert, which had finally cleared the Birnenwald.

Farther west, the advance of the 20th and 2nd Panzer Divisions was halted by counterattacks from Grigorev’s 16th Tank Corps. Captain Wolfgang Darius, commander of 20th Panzer’s Pz. Abt. 21, observed a Soviet tank brigade preparing to attack.

“I quickly ordered my 48 panzers to turn toward the enemy,” he wrote 44 years later. “As we advanced our forward line would stop and fire two rounds and then let the second line move forward to do the same. The Russians were caught off guard, and we continued to destroy tank after tank until the enemy left the field. From July 5 to July 7 my Abteilung was credited with the destruction of 159 enemy tanks.”

Supported by Darius’s panzers, Colonel Rudolf Demme’s PGR 59 succeeded in advancing a couple of kilometers. Darius was then ordered to support a drive by the II/PGR 112 toward the Swepa Valley. By 1615, the 112th had been able to establish a forward line in the area, but constant Soviet counterattacks made further progress impossible for the time being.

East of Ponyri, the 86th moved out at 0530 in conjunction with the 292nd. Its first objective was to recapture the trenchline that the Soviets now once again occupied. Senior Corporal Heinrich Kaup was in the 3rd Company/GR 184. As the company advanced the Russians opened up with a storm of bullets. Within a few minutes, most of officers had been killed or wounded.

“I realized that I had to act decisively,” he wrote decades after the war. “I could not hesitate, so I collected a group of seven men and placed them under my command. We picked up extra grenades from the dead and wounded and then advanced, throwing the grenades as we went. In this way we cleared the trench and then defended it until the rest of the company would join us. For this action I would later receive the Knight’s Cross, but it was really the bravery of the men that joined me that deserve the credit.”

The 86th continued to advance assisted by the 1st and 2nd Companies of Major Erich Käppler’s Stug. Abt. 177. Soviet air power hampered the advance, and the division was only as far as Hill 257.1, some six kilometers northeast of Ponyri Station, by 1130. Soviet artillery and antitank guns dug in on the reverse side of the hill stopped the advance in that sector. Farther west, near the 1 Maja collective farm, elements of the 86th, assisted by Pz. Jäg. Abt. 654, ran up against the 1021st Rifle Regiment. A back and forth battle centered on Hill 253.5, about four kilometers northeast of Ponyri Station, that finally ended with the hill in German hands at the end of the day.

At Ponyri itself the German barrage started at 0530. When it lifted, the 507th and 508th advanced. Supported by some assault guns from Stug. Abt. 244, Hahne’s 507th moved toward the lines of Enshin’s 1019th Rifle Regiment and the dug in antitank guns of the 1188th and 1180th Antitank Regiments. German forward observers were able to pinpoint the main Soviet defenses and called in a steady stream of artillery fire on those positions. By 0900, Hahne was able to report that the northern section of Ponyri was mostly secure.

Efforts to advance farther were stalled by defenses just south of the village. There, the main body of the 1019th occupied heavily fortified positions. Soviet artillery pounded the Germans inside Ponyri and threw counterbattery fire at the German guns, while Soviet aircraft prevented massed Luftwaffe attacks on Enshin’s troops.

To Hahne’s right, Zierhold’s 508th hit the left flank of the 1019th. The attack began the same way as Hahne’s had. By 0700, the 508th was advancing on the center of Ponyri, but it ran into heavy fire on its flanks. About an hour later Zierhold’s men were battling for the Ponyri Railway Station while being pounded by enemy artillery. Near the station the Germans engaged Soviet infantry and tanks in a fierce battle. Several German assault guns were knocked out in the seesaw, ebb and flow action.

The unrelenting German assault finally forced the Russians to withdraw to the southern part of the village. However, Soviet reinforcements were able to counterattack and force the Germans back to positions around the train station. A report of a large mass of Soviet tanks approaching the area halted the German attack and forced both the 507th and 508th to take a defensive posture. When Harpe heard the report of enemy tanks approaching, he ordered the entire XLI Panzer Corps to go on the defensive.

For the 292nd, taking only a portion of Ponyri was a costly affair. Casualties for July 7 included 106 killed, 413 wounded, and 26 missing. Many of the line companies were down to 70 percent of their July 4 strength. On the Soviet side, Enshin reported 273 dead and many more wounded. The 307th had prevented a German breakthrough, but it too had paid a heavy price.

The tanks reported by Luftwaffe reconnaissance were units of Sinenko’s 3rd Tank Corps. Elements of the corps were recognized by German intelligence, and Harpe reaffirmed his previous order by instructing his three divisions to work through the night constructing in-depth defensive positions. A short statement was distributed to all commands down to the company level. It read: “An attack by powerful portions of the 3rd Tank Corps is expected on July 8.”

Harpe’s commanders wasted no time in preparing for the impending attack. Schlieben’s 18th Panzer, located southwest of Ponyri, was put under Kluge’s control for tactical purposes. The division’s Pz. Abt. 18 would serve as the 292nd’s reserve force. Jungenfeld’s remaining Ferdinands and Grizzlies were positioned north of the Ponyri Station and would serve as the corps reserve.

While GR 508 defended the southern and middle sections of Ponyri, Hahne’s 507th, holding the northern part of the village, was placed under the control of the 86th Infantry. This was necessary to prevent a rupture of the line at the junction of the regiment and Weidling’s division.

The Soviets were also shifting forces for the upcoming attack. Onuprienko’s 6th Guards was ordered to shorten its line facing the 18th Panzer. Pukhov moved Gorishnii’s 75th into positions on Onuprienko’s vacated left flank. Enshin’s mauled 307th was barely holding onto a portion of southern Ponyri, and Pukhov ordered Maj. Gen. Aleksandr Rumiantsev’s 4th Guards Airborne Division to take positions south of the village as a reserve force. Facing Weidling’s 86th were the remnants of the 129th Tank Brigade and the 1442nd Self-Propelled Artillery Regiment, while the 27th Guards Separate Tank Regiment occupied positions south of Ponyri.

As Sinenko’s 3rd Tank Corps arrived, the units deployed behind the 307th and 4th Guards Airborne. Maksimov’s 103rd Tank Brigade was placed on the corps right flank, while Colonel G.A. Kokurin’s 51st Tank Brigade and the 57th Motorized Rifle Brigade took positions behind the central and southern sectors of Ponryi. Colonel Fedor Konovalov’s 50th Tank Brigade would be held in temporary reserve.

While Model approved Harpe’s order to go on the defensive, he still planned to continue his assault west of the village with Lemelsen’s XLVII Panzer Corps. Once again, his goal was to sever the junction between the 70th and 13th Armies in the Samodurovka-Teploe area about 20 kilometers west of Ponyri. Lübbe’s 4th Panzer and Kessel’s 20th Panzer would be at the point of the attack.

Pukhov opened his assault on Ponyri with a heavy artillery barrage at 0400 on July 8. The artillery, ranging up to 203mm guns, was supported by several 300mm Katyusha rocket launchers.

At 0430, Enshin ordered the remnants of his 307th forward. He was supported by the 57th Motorized Rifle Brigade and 20 tanks. Further east about 50 tanks from the 103rd Tank Brigade also rolled forward. They ran into an ambush laid by Käppler’s Stug. Abt. 177. Within 10 minutes there were 12 T-34s burning, with the rest hastily withdrawing.

Hahne’s 507th took the brunt of Enshin’s attack. The 1021st Rifle Regiment, led by Captain S.A. Sukiasian, was supported by the 57th Motorized Rifle Brigade and about 30 of Maksimov’s tanks. Red Air Force bombers hit the German positions as the Russians advanced. Sukiasian and his supporting units were able to take the northern outskirts of Ponyri and then move against the 1 Maja collective farm.

The Germans mounted an immediate counterattack with Grosskreutz’s Stug. Abt. 244 and part of Stug. Abt. 177 along with some Ferdinands, the 2/Pz. Abt. 18, some self-propelled antitank guns from Pz. Jäg. Abts. 292 and 18, and other units. Stukas were called in to support the counterattack, which began at 0810 under cover of German artillery.

A fierce firefight commenced with the Germans running headlong into the attacking Russians. As the Soviets were pushed back, the 507th regrouped and moved to regain its line. Firing at T-34s that had infiltrated behind his position, Sergeant Willi Zahn managed to destroy seven tanks within 15 minutes with his medium French antitank gun. The commander of the 14/GR 507 recommended Zahn for the Knight’s Cross, but Zahn did not live to receive it. He was killed on July 16, just two days before the award was approved.

The Russians continued to press their attack on Ponyri. Switching his attention to Zierhold’s GR 508, Enshin ordered his 1023rd Rifle Regiment, supported by tanks and artillery, to drive back the enemy in the southern sector of the village. As artillery shells slammed into Zierhold’s line, the Russians struck at selected points in strength, forcing the entire regiment to either retreat or become flanked. Although the Soviets failed to achieve a decisive breakthrough, they did manage to retake several areas of southern Ponyri as well as the water tower just south of the train station.

Zierhold’s men counterattacked, and losses on both sides mounted as several efforts to retake the water tower failed. A German combat group finally managed to wrest control of the tower away from the Russians and then had to fend off several Soviet efforts to regain it. The battle continued into the night with the opposing forces silhouetted against the fires raging in the village. Ammunition became a problem for the Germans holding the tower, and they were eventually forced back, giving control of the area back to the Russians.

Model’s own attack west of Ponyri began around 0800. Saucken’s 4th Panzer moved forward to support the 20th Panzer in the Samodurovka area. Meanwhile, Lübbe’s 2nd Panzer attacked Soviet defenses in the Olkhovatka area with the 9th Panzer supporting his left flank. Both assaults ran into extremely heavy resistance from elements of the 17th and 19th Guards Tank Corps.

The Germans threw themselves against the Russian defenses again and again. They captured a trenchline near Samodurovka only to face new lines behind it. The cornfields made unit cohesion difficult, and casualties mounted. A German observer watching the attack noted that all of the officers of the 5/PGR 112/20 Pz. had been killed or wounded within an hour.

All the German assaults stalled in the face of heavy Soviet fire. Russian artillerymen fired over open sights at the advancing German armor while other artillery units pinned down the panzergrenadiers that were supposed to accompany the panzers. The village of Teploe, about three kilometers south of Samodurovka, was captured by the Germans. The move threatened to cut the junction between the 70th Guards and the 175th Rifle Divisions. To counter the threat, Pukhov moved Maj. Gen. Kisilev’s 140th Rifle Division and Colonel N.M. Bubonov’s 11th Guards Tank Brigade forward to block a further advance.

By the end of the day, the panzer assault had gained little ground west of Ponyri, and Model’s troops were exhausted. Model was forced to call off the attack and ordered his armored divisions to regroup for a new attack in the morning. New defenses were hastily dug, and the men settled in for the night, trying to get some sleep in the face of intermittent Soviet artillery fire.

On the morning of July 9, Model once again tried to use his panzer divisions as a battering ram, but Pukhov had reinforced the area west of Ponyri with even more tank and antitank units. As a result, when the panzers and accompanying panzergrenadiers were able to make some headway, they came under increasing fire on their flanks. New minefields were encountered, and the German engineers paid a heavy price trying to clear them. A Soviet attack on the 2nd Panzer threw the division into disarray and forced it to halt. Because of this setback, Model once again stopped the attack to let the division regroup.

In Ponyri the beleaguered 292nd came under heavy artillery fire on the right flank of GR 508 before dawn. The division had been given the standard order for the 9th—“Clear the enemy from Ponyri.”

For this attack, GR 507 would be supported by the 3/Pi. (engineer) BN. 292, the 2nd and 3rd Companies of Stug. Abt. 244, 1/Pz. Jäg. Abt 292, and four Ferdinands from Pz. Jäg. Abt. 653. The regiment was to take Hill 226.5 just south of Ponyri and Hill 239.8 east of the village and then block any Soviet reinforcements from entering the area. Part of the regiment would then sweep south to meet up with Zierhold’s 508th, which would advance from the southern part of the village and then swing southeast. Zierhold would be supported by 1/Stug. Abt. 244, the rest of Pz. Jäg. Abt. 292, 1/ Pi. BN. 292, and the 2/Pz. Abt. 18 from the 18th Panzer.

Once the regiments linked up it was hoped that the 307th, 57th Motorized, and the 27th Guards Tank would be encircled and destroyed. The final objective of GR 508 was Hill 256.9, about 2,500 meters southeast of the jump-off position. An attack by PGR 52 would cover Zierhold’s right flank.

The German artillery barrage began at 0605, and at 0615 the two regiments started their attack. By 0700, the 507th was in the open terrain south of Ponyri. There, they came under Soviet artillery fire that forced them to take cover. Two of the regiment’s battalions were pinned down, but Major Josef Fischer’s 11/GR 507 did manage to advance 1¼ kilometers to take Hill 239.8. However, Fischer’s battalion had no support on either flank and was forced to halt after taking the hill.

Things were just as bad for the 18th Panzer’s supporting attack. The bulk of Pa. Abt. 18, which was to support Seidlitz’s PGR 52, assembled in the wrong area. To make things worse, as the first panzers crossed the Snova River they collapsed the bridge they were using, leaving the majority of the tanks stranded on the wrong side of the river.

Seidlitz began his attack without the panzer support and immediately came under fire. Without the armor, the attack was halted almost as soon as it had begun.

With neither GR 507 nor GR 508 making any progress, it was decided to switch the main effort of the 292nd to clearing out the southern portion of Ponyri. Zierhold’s GR 508 had that honor. Backed up by the remaining guns of 1/Stug. Abt 244, they were ready to go again.

The Russian forces facing them had sustained heavy casualties, and units had become intermingled, but they still held firm. They were also backed up by a tremendous range of artillery pieces, vital in holding their positions. In the air both sides were fighting for superiority, and the sky was filled with aircraft trailing smoke as they plunged toward the earth.

Panzer Abteilung 18 had finally found its way to the right area and was ready to support PGR 52. As Seidlitz’s men began to move forward, the panzers rolled out in front of them. They ran into a wall of artillery and antitank fire and were only able to advance a few hundred meters as they suffered casualty after casualty. The panzergrenadiers made even less progress. The war diary of Stug. Abt. 244 described the scene: “During the afternoon the Russian artillery increased to an unheard of intensity, especially against (Hill) 248.9 and the fruit orchard east of there. At the same time it (the Soviets) introduced a Russian counterattack from Ponyri south.”

A company of Russians, commanded by Senior Lieutenant Ivan Ryabov, stubbornly hung on to the Ponyri schoolhouse despite numerous German attempts to take it. When one German assault threatened to overrun his defenses, Ryabov called for rocket fire to hit his position, causing him some casualties but driving the Germans back.

The fighting continued unabated up and down the German line of assault. In another attempt to breach Soviet defenses, the 1st and 2nd Companies of Pz. Abt. 18 sustained heavy losses from flanking fire as they once again led PGR 52 forward. Seidlitz’s men also sustained more casualties, and the regiment was so depleted that the 18th Panzer reserve, Colonel Fleischauer’s PGR 101, was ordered forward so that the line between the 18th and the 292nd would not be severed. At Ponyri the depleted Div. BN. 292 was also ordered into the line to plug a gap between GR 507 and 508.

As the fighting intensified the Soviet units holding central Ponyri were eventually surrounded. Oukhov rushed Colonel Ivan Konev’s 3rd Guards Airborne Division to a reserve position southwest of the village and ordered Rumiantsev’s 4th Guards Airborne into Ponyri itself to rectify the situation. Rumiantsev’s men were soon in position, and they hit the forward elements of both the 507th and 508th. As night descended, both the 18th Panzer and the 292nd were ordered to dig in and hold on to their meager gains at all costs.

Harpe, after visiting Kluge’s headquarters, decided that the 292nd was spent. Line companies had an average strength of 20 men, with some of them having sergeants or corporals commanding them. He requested that Maj. Gen. August Schmidt’s 10th Panzergrenadier Division be taken out of reserve and be sent to replace the 292nd. Model agreed, and Kluge was informed that the turnover would occur the following night.

The Soviets were not about to give the Germans in Ponyri any rest. During the final hours of July 9, a battalion of Konev’s 3rd Airborne attacked and breached the line of Div. BN. 292 south of the Ponyri water tower. It managed to move into an area in the north end of the village about a kilometer behind the main line of GR 508.

At 0700, the Germans counterattacked, using eight assault guns from Stug. Abt. 244 and a company of grenadiers. With the assault guns in the lead the Germans sealed off the penetration, trapping the Soviets in a pocket. A followup attack commenced at 1100 and smashed the trapped battalion. Schmidt officially took control of Kluge’s sector at Ponyri at 1200 on July 10, but his units had not yet arrived on the scene. Meanwhile, the Soviets continued to attack GRs 507 and 508 with tanks and infantry. With the help of Colonel Grosskreutz’s Stug. Abt. 244, the attacks were repulsed.

In the 86th Division’s sector, the 4th Guards and the 51st and 129th Tank Brigades hit the division’s right flank and tried to force their way into northern Ponyri. The fighting continued into the evening with the Germans, supported by Käppler’s Stug. Abt. 177, fending off the attacks.

The assault guns became the backbone of the defense. The commander of the 2/Stug. Abt. 177, 1st Lt. Kurt Zitzen, moved his five assault guns forward as night was falling. He wanted to try to cut the Russian supply line in his sector. As he moved forward he spotted about 30 Soviet tanks, which were preparing to support an infantry attack. In the fading light Zitzen and his men were able to approach to within 200 meters of the enemy.

Opening fire, Zitzen continued a slow advance. In a 15-minute fire fight in which the opponents were sometimes as close as 30 meters, Zitzen’s company destroyed 15 heavy (probably T-34s) and one super heavy (KV I or KV II) tanks and immobilized four more. Zitzen destroyed six of the enemy tanks himself. The survivors made a hasty retreat, totally disrupting the planned attack.

As the fighting died down, units of the 10th Panzergrenadier Division arrived, and the 292nd gratefully turned their positions over to Schmidt’s men. As the 292nd departed for the rear, Pz. Abt. 18 was also pulled out of the line to give its men a rest and to perform much needed maintenance on its surviving vehicles.

On the Soviet side, Kluge’s nemesis, Enshin’s 307th, was also pulled out of the line, its positions taken over by the 16,000 men of the 3rd and 4th Guards Airborne. More units, including Maj. Gen. Ilia Dudarev’s 2nd Guards Airborne Division, were also on the way.

By July 11, it was clear that Model’s push on the northern flank of the Kursk salient was almost finished. While Manstein continued to push forward on the southern flank, the 8th Army was now on the defensive. The day passed relatively quietly, except for the incessant Soviet artillery fire and some probing attacks.

Things changed on the 12th, when the Soviets unexpectedly attacked the neighboring 2nd Army in force north of Orel. It marked the beginning of a massive Russian counterattack codenamed Kutuzov after a famous czarist general in the Napoleonic Wars.

Kutuzov effectively ended Zitadelle in the north. Even as the great tank battle at Prokorhorovka was taking place in the south, Model was ordered to send the 18th Panzer and schw. Pz. Jäg. Abt. 654 north to help contain the Russian attack on the 2nd Panzer Army, which was making considerable progress. Schmidt was ordered to broaden the 10th Panzergrenadier Division’s line to cover the sector that would be left vacant by the 18th Panzer, and major elements of the 292nd were ordered to prepare to return to the line.

The Russians around Ponyri turned their attention to Weidling’s 86th on the morning of the 12th and then switched to Ponyri itself, hitting elements of Major Walter von Thein’s GR 20 (mot.), who had just relieved the 292nd. After an hour-long fight the Soviets finally withdrew.

July 13 saw a repeat of the sporadic attacks, but by then all eyes were focused on the battle in the 2nd Panzer Army’s sector and on Manstein’s actions in the south. Model’s remaining panzer divisions were in desperate need of maintenance, and individual elements of those divisions had to be pulled out of the line.

The 14th was relatively quiet, with the Germans realigning their forces and the Soviets preparing for an attack the following day. Besides the three Guards airborne divisions facing Ponyri, Rokossovskii had ordered Colonel N.N. Zaiiulev’s 55th Rifle Division to be transferred from the 60th Army to take the lead in the planned assault. Sinenko’s 3rd Tank Corps would support the attack.

At 0415 on the 15th, a hail of artillery shells and Katyusha rockets hit the German line. Supported by more than 300 artillery pieces, the Russians advanced. At Ponyri the 3rd and 4th Guards Airborne Divisions were met with continuous machine-gun fire, stalling the attack.

East of Ponyri, Zaiiulev’s fresh 55th Rifle Division was able to breach the line of Weidling’s 86th. Hahne’s GR 507, which was the corps reserve, was ordered forward to help the division. The remaining guns of schw. Pz. Jäg. Rgt. 656 and Stug. Abts. 177, 244, and 189 were ordered to hit the tanks accompanying the Russian infantry. Moving into ambush positions, the guns began picking off the oncoming enemy armor. A total of 11 Soviet tanks were destroyed by Lieutenant Hermann Feldheim, a gun commander in the 1/schw. Pz. Jäg. Abt. 656, and several other gun commanders claimed multiple kills. The Soviet attack lasted four hours before it was called off.

Pukhov tried again at 1300. Casualties were high on both sides, but the Russian losses could be replaced while the Germans’ could not. Harpe knew that his men could not hold out much longer, and at 1610 he issued orders for his divisions to withdraw to new positions anywhere from ½ to three kilometers behind the main line. At 0430 on July 16, Soviet patrols reported that Ponyri had been abandoned by the enemy.

With Operation Kutuzov the Soviets began a drive that would take them to Berlin in less than two years. The Germans could not make good their losses in men and material that were incurred during Zitadelle, and it would show in the months to come.

The battle for Ponyri was hailed by the Soviets as the “Stalingrad of Kursk.” While that may be an exaggeration, it is certainly true that once Model decided to take Ponyri instead of immediately flanking the village with his panzers, cutting its supply line, and leaving it for followup infantry forces to capture, it drew units from both sides like a magnet. Giving the Soviets time to reinforce the area also proved to be a costly error. In all, the 9th Army had only managed to advance 12-15 kilometers during the entire battle.

Model continued to have a reputation as a good defensive fighter on the Eastern Front. He commanded various army groups in the East during the retreats of 1944 and was promoted to field marshal. Sent to the West after the Allied invasion, he continued to use his defensive skills against the British and Americans, but the overwhelming superiority of men and material, especially Allied air power, proved to be too much.

When his Army Group B was trapped in the Ruhr Pocket, there was little Model could do. Instead of surrendering, he took his own life on April 21, 1945.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments