By Cleve C. Barkley

In early 1942 things could have hardly looked bleaker for the Allies. In Europe, Hitler’s war machine had steamrolled across the entire continent and was now battling before the gates of Moscow. Across the Mediterranean, General Erwin Rommel’s Panzerarmee Afrika seemed unstoppable as it prepared for the final push into Egypt and the coveted Suez Canal. And German U-boats prowled the North Atlantic, seemingly sinking ships at will, some within sight of the American mainland. In the Far East, Japanese conquests had spread across Asia and the Pacific Ocean like a blood-stained tide. It truly was a world war. But who remembers Madagascar?

A Potential Threat From Madagascar

After the fall of France in June 1940, many of her far-flung colonies were tethered to the new Vichy regime. Among them was Madagascar, the massive island off the southeastern coast of Africa, which remained an isolated backwater until March 1942, when Japanese forces had not only taken vital Singapore but also threatened British India by striking deep into Burma.

After the Allies observed Japanese naval demonstrations off the coast of Ceylon in the Indian Ocean, it was believed that further Japanese expansion was inevitable. Suddenly, Madagascar was elevated to priority status. Earlier the Vichy French had permitted the Japanese to enter Indochina. If the Japanese were granted similar access to Madagascar’s deep-water harbor of Diego Suarez it was feared that enemy submarines and aircraft would commence wreaking havoc on the British convoys that passed the tropical island en route to the East by way of the Cape of Good Hope.

Such an occurrence would strangle the lifelines to British forces in Egypt and India and all but assure victory for the Axis powers. Having all the earmarks of a potential disaster, it was decided that Diego Suarez should not fall into enemy hands.

Operation Ironclad

Dubbed Operation Ironclad, the British devised a plan that called for Diego Suarez to be taken by storm. The northern tip of Madagascar resembles an arrowhead with the eastern and western shorelines notched so severely as to create its neck. Deep within the eastern notch lies Diego Suarez with the port of Antsirane—population 30,000—to its south, separated by a bay. Knowing that the harbor’s entrance was narrow and heavily defended, it was decided that the landings would take place on the northwestern coast, followed by a rapid march eastward to take both towns from the rear. Speed and stealth were imperative.

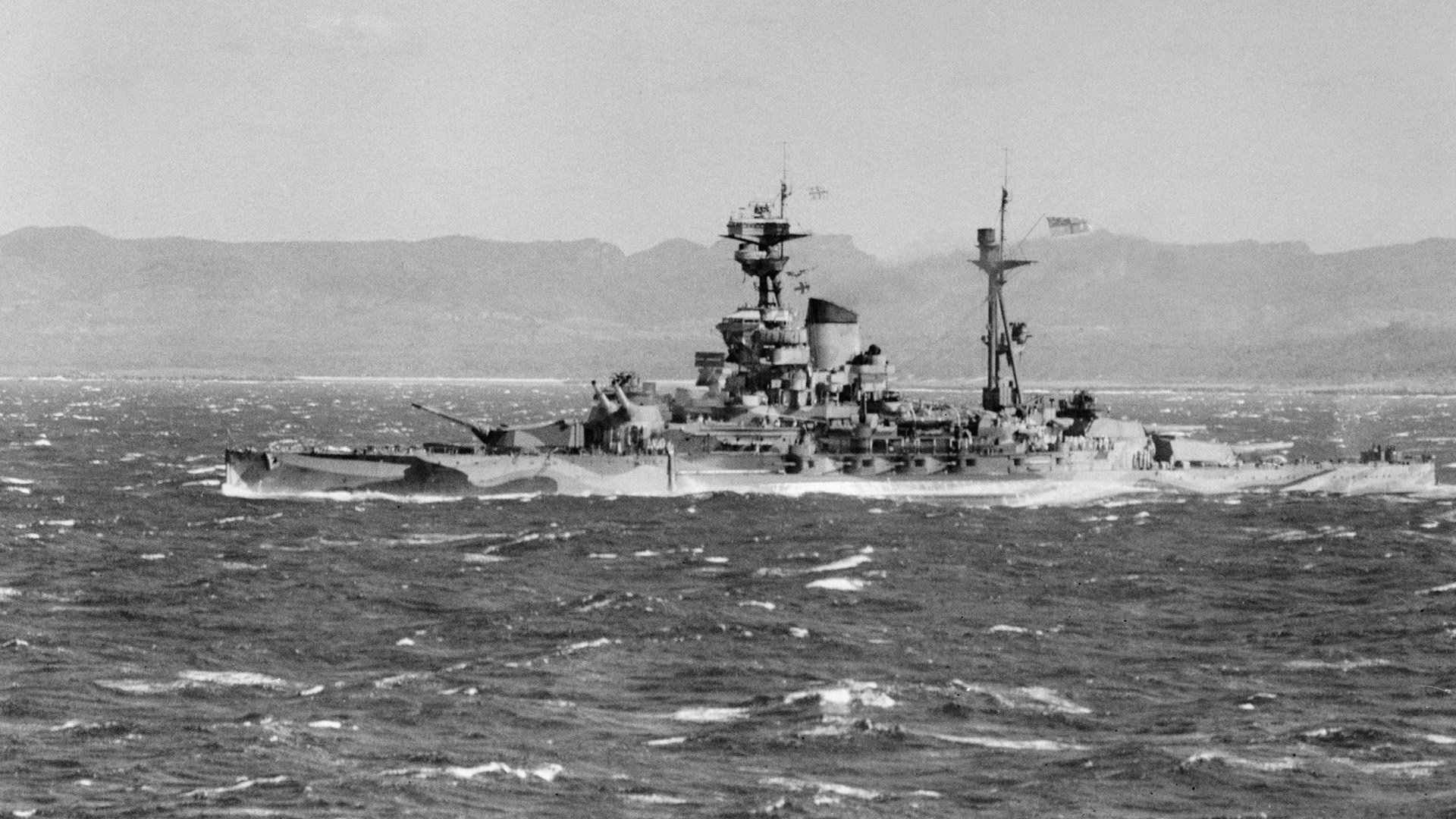

Overall command of the operation was given to Rear Admiral Edward N. Syfret, Royal Navy, whose task force would steam down the West African coast to Durban, South Africa, before proceeding to Madagascar. With the battleship HMS Ramillies as flagship, the fleet comprised a number of cruisers, destroyers, and lesser warships along with the aircraft carrier HMS Illustrious, all escorting an assortment of transports. An additional carrier, HMS Indomitable of the Eastern Fleet, would rendezvous as they neared their target.

The land element, Force 121, had departed Britain via convoy on March 23 and joined Syfret at Freetown, Sierra Leone. Commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert Sturges, Royal Marines, its primary component was Brigadier Francis Festing’s 29th Independent Brigade, which had received extensive training in amphibious operations while in Britain. The 29th would be augmented by No. 5 Commando and B Special Service Squadron, an armored formation consisting six Valentine tanks and six Tetrarch light tanks, each armed with a two-pounder gun and one Besa machine gun. The crewmen, all volunteers, had been cross-trained in commando tactics. Also attached was 455 Light Battery, consisting of two 25-pounder guns and four 3.7-inch light howitzers.

Realizing this force alone would be greatly challenged by the sheer scope of the operation, Sturges managed to have the 13th and 17th Brigades of the India-bound 5th Division attached, with provision that each be returned to its parent organization upon completion of the mission. In all, Sturges commanded about 15,000 men.

The Vichy French Defenses on Madagascar

The Vichy French, administered by Governor General Armand Annet, believed that any attempt to seize Diego Suarez could only come from the more accessible east, so they planned their defenses accordingly. With the harbor entrance being a mere slit cut between towering cliffs, the French wisely placed five coastal batteries—some mounting massive 330mm guns—on the Orangea Peninsula, which formed the strait’s southern palisade.

Posted near the port of Antsirane was Colonel Rouves’s 2nd Mixed Regiment comprised of French colonials, Senegalese Tirailleurs, and Malagasy soldiers, with several companies billeted at Diego Suarez across the bay. While the Malagasy were of dubious quality, the colonials and Senegalese were top notch with the latter being ranked among the most ruthless killers in the world. There were also several naval vessels and a small air contingent.

Straddling a narrow isthmus a couple thousand yards below Antsirane was a string of intricate trench works studded with pillboxes, each enjoying clear fields of fire. Called the Joffre Line, it was a strong series of defensive fortifications. The flanks were anchored by Fort Caimans to the west and Fort Bellevue to the east with heavily foliaged terrain falling sharply from each to a swampy mangrove-lined shore, making any flanking maneuver extremely hazardous. Two thousand yards long, it was a daunting position.

Roughly 20 miles due west, the coast was so congested by treacherous reefs and rocky outcroppings that any invasion from that direction was deemed foolhardy at best and virtually impossible by night. Nonetheless, all approaches had been heavily mined. Only two bays held suitable landing beaches—Courrier Bay to the north and smaller Ambararata Bay about seven miles to its south—both guarded by a battery of 138mm guns perched atop a 50-foot cliff overlooking Courrier. It was believed that this battery, known as Coastal Defense Battery Seven, would be sufficient to delay any incursion long enough to allow Vichy forces to man the Joffre Line. Farther inland a stone observation tower—bearing the unlikely name of Windsor Castle—kept vigil from a sheer elevation north of Courrier. Only one company safeguarded these positions. All told, the forces defending Antsirane numbered less than 4,000.

Catching the Defenders Off-Guard

Departing Durban on April 28, 1942, Admiral Syfret’s task force arrived off the northwestern shore of Madagascar late on May 4. The plan called for Lt. Col. William Sanguinetti’s No. 5 Commando and Company B, 2nd Battalion East Lancashire Regiment to land at Courrier Bay and knock out Coastal Defense Battery Seven as well as another suspected emplacement before proceeding cross-country via the Andrakaka Peninsula to occupy Diego Suarez itself. Meanwhile Brigadier Festing’s 29th Independent Brigade would conduct a 21-mile march inland from Ambararata Bay to take the port city of Antsirane from the south. It was hoped that the entire operation would be swift and trouble free.

In the wee hours of May 5, minesweepers cleared channels for the troopships while the cruiser Devonshire stood by, ready to respond to the first inkling of opposition. At 2:30 am, the landing craft holding No. 5 Commando commenced the 10-mile journey to Red Beach, nestled on the northern shore of Courrier Bay. They had hardly pulled away from their mother ship, it seemed, than two shattering explosions rent the night within 15 minutes of each other—the minesweeper Romney had accidentally detonated two mines while clearing the bay. Aboard Ramillies, Admiral Syfret and General Sturges grimaced, fearing that the element of surprise had surely been lost. The commotion did not go unnoticed in the assault boats either, where officers snarled, “Fix bayonets!” in anticipation of a hot reception.

Tasked with eliminating Coastal Battery Seven, three troops hit Red Beach North at 4:30 am, expecting the worst, but not a shot was fired. To their good fortune, Romney’s mishap had not betrayed their approach. Immediately, commandos scaled a 50-foot escarpment and surrounded the battery only to discover that the guns were completely unattended. Hardly believing their good fortune, they quickly disabled the guns then closed in on some nearby barracks. Dawn was just breaking as they peeked inside, and they were thrilled to discover that the entire garrison was fast asleep. Obviously, the French clung to the belief that a nighttime invasion from the west was impossible. Now they would pay for their assumption.

The commandos burst in brandishing weapons and shouting loudly, startling the drowsy inhabitants. The majority were Malagasy, most of whom gave up without a fight. A few French officers and NCOs reacted swiftly and launched a vicious counterattack. One Frenchman lunged with his bayonet and skewered a commando’s arm. Another charged only to be cut down by a curt burst from a Thompson submachine gun, while Lieutenant “Dopey” Rose all but blew the head off a third with a single slug from his Colt .45 pistol. That settled things. Realizing that opposition was futile, the Frenchmen dropped their weapons and threw up their hands.

White Flag Over Windsor Castle

Then someone noticed that a white flag had been hoisted above the observation tower on precipitous Windsor Castle, farther uphill. Captain John “Chips” Heron was ordered to bring these soldiers in. As his patrol neared the crest a number of Senegalese sprung from a trench with hands held high, but just as Heron stepped forward several grenades arched from behind the supposedly surrendering soldiers and tumbled downhill. Commandos scattered.

The bombs exploded, and Heron groaned as fragments perforated his legs and buttocks. Enraged by such treachery, his men rushed the Senegalese and killed them all. Still conscious, Heron ordered his command to fall back, and once they were safely down Navy gunners and fleet aircraft pounded the heights until no more activity was seen.

While all this occurred, two other troops had landed at Red Beach South with the mission of eliminating the suspected second battery. Finding the intelligence erroneous, these men marched north to link with their comrades at the appointed rendezvous. Joined by the attached company of 2nd East Lancashire, Sanguinetti’s command, some 700 strong, commenced its eight-mile trek across the Andrakaka Peninsula to Diego Suarez.

Out at sea, Admiral Syfret and General Sturges sighed with relief upon receiving word of the commando success. With Coastal Battery Seven no longer a threat, Festing’s 29th Independent Brigade could now proceed unmolested to Ambararata Bay.

First in were the 1st Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers at Green Beach cupped to the south and 2nd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers, which swarmed over White Beach a little farther north, both on time and without opposition. Only at Blue Beach, situated on a spit of land two miles above White, was there any semblance of resistance when a machine gun took the boats of 2nd Battalion East Lancashire Regiment under fire. The gun was quickly silenced by a company of Welsh Fusiliers marching from the south. By 6:20 am, 2,300 troops were ashore.

A Long Endurance March

While the west coast landings were under way, the light cruiser HMS Hermione was staging a lively demonstration off the east coast, firing smoke and star shells in the vicinity of Amodivahibe Bay, which the French believed to be the only suitable site for amphibious operations. At daybreak dummy parachutists floated onto the Orangea Peninsula while the Fleet Air Arm pounced on French ships anchored at Diego Suarez, sinking or damaging all but the gunboat D’Entrecasteaux. Other planes crippled the Vichy air force at Arrachart airfield, five miles south of Antsirane. Special Operations Executive agent Percy Mayer had managed to sever telephone lines between Windsor Castle and Antsirane, denying the French vital communications during the actual invasion. Combined, all these actions reinforced the French belief that an invasion could only come from the east.

Back at Ambararata Bay, Brigadier Festing received the troubling report that Green and White Beaches were incapable of supporting heavy vehicles, so the landing craft ferrying his artillery and tanks were being diverted to the much firmer Blue. It was a delay he could hardly afford, for speed was of the essence. Not willing to wait, he ordered his infantry to proceed without them. The Royal Welsh Fusiliers took the lead with the balance of the brigade trailing. Antsirane lay 21 hot and dusty miles to the east.

The march quickly evolved into a trial of endurance. The heat became insufferable as the men plodded through scrub and craggy stone, longing for relief but receiving none. Several miles in a number of Bren gun carriers and motorcycle scouts overtook them, raising clouds of choking dust as they claimed the lead.

At midmorning an automobile carrying a French naval officer and three sailors blundered into the vanguard and were taken prisoner. Brigadier Festing presented them a letter addressed to Governor General Annet stating the long-held British desire that the Vichy capitulate and join the Allied cause, thereby avoiding further bloodshed. Charged with its delivery, the rattled Frenchmen were released and the arduous march resumed.

The Armored Advance

By 11 am, the Bren carriers had bypassed the town of Anamakia and were approaching a rocky ridge, which rudimentary maps indicated was only passable through a boulder-strewn saddle called the Col de Bonne Nouvelle. The scouts were elated, knowing that just beyond the pass the road swung abruptly north toward their goal of Antsirane, barely three miles farther. But their joy was short lived.

Suddenly, the boulders, bordering grasslands, and neighboring hillocks exploded with machine-gun and rifle fire. Vehicles veered left and right. Brigadier Festing, who had joined the vanguard in his personal carrier, was obliged to help guide his vehicle to shelter after the first burst shattered his driver’s hand.

No sooner had the carriers taken cover than two Valentine tanks trailed by one of the lighter Tetrarchs clattered onto the scene. Festing battered the lead tank’s turret with his ever present walking stick, and up popped Major Jocelin Simon. Festing promptly ordered Simon to enter the gap and clear out the menacing machine guns. The major’s hatch clanged shut, and away he went.

Bullets clattered against iron hulls as the tanks entered the trough and used their two-pounders with telling effect. At one point 10 Senegalese broke from cover only to be mowed down by the lead Valentine’s machine gun. Other tanks blasted pillboxes or targeted enemy trenches, and before long the gunfire slackened, then died. Realizing that further maneuver in the rugged terrain was impossible, Simon ordered his command to push on and out to the other side. Soon after, two more Tetrarchs arrived and chased after the column as it waddled toward Antsirane.

Disaster at the Joffre Line

Led by Lieutenant Whitaker’s Valentine, Simon’s juggernaut continued single file down the solitary road, confident they had accomplished their mission. Roughly 3,000 yards farther, Whitaker’s tank negotiated a blind turn only to come face to face with a truckload of Senegalese racing to the aid of their comrades at the pass. Startled, Whitaker’s gunner riddled the vehicle with his Besa, killing or wounding the lot. The next moment Whitaker’s Valentine shuddered, nailed by a solid-shot armor-piercing round. A track unraveled. A second shot racked the turret. Hatches swung open, and two men bailed, leaving the driver slumped in his seat, dead. As the survivors scrambled for cover, a machine gun bowled the gunner, prompting Whitaker to pivot mid-stride to help him to shelter.

Simon’s Valentine surged forward, firing as it went, but it too was hit, with the concussion knocking the driver senseless. Without guidance the tank advanced of its own accord. In rapid succession another round struck a driving sprocket, while a third jammed the turret. His tank now useless, Simon ordered the crew to bail from the still moving vehicle. Simon and his gunner leaped clear, but to their horror their stunned driver tumbled directly in front of a churning tread and was horribly mutilated. Crewless, the tank clattered on until immobilized by boulders.

Both Valentines were now out of action. The three Tetrarchs had hardly commenced laying covering fire for their dismounted comrades than two were hit and burst into flames. In the first, Corporal Watkins was killed. His severely burned mates managed to pull themselves free. The gunner and driver of the second Tetrarch were wounded, but their commander, Lieutenant Carlisle, was able to extract the driver and drag him to cover before darting back to rescue the gunner. His crew now safe, Carlisle once again braved shot and shell to remove a Bren gun from his broiling hulk before rejoining his comrades in the bush.

It was a disaster. Simon’s command had run headlong into the Joffre Line. Somehow aerial reconnaissance had overlooked the entire strongpoint, and its presence came as a complete surprise. Shocked, Simon raced to the lone surviving Tetrarch and ordered Lieutenant Astles to rush back to brigade to apprise Festing of its existence. Astles’s tank pivoted and scurried away.

The scene among the damaged and burning tanks quickly revealed Simon’s last stand. He commanded only eight men, five of whom were wounded. Having been trained in commando tactics, his men were not about to give up. Survivors scavenged the wreckage for additional weapons and secured a second Bren gun as well as a Thompson submachine gun. Simon formed a defensive perimeter, tended his wounded, and waited for rescue.

The French had other ideas. At once Senegalese Tirailleurs launched a spirited bayonet attack but were driven back by heavy fire. But the Africans were brave soldiers and charged twice more. During the third rush the gallant Whitaker was killed in hand-to-hand combat, most likely gutted by a bayonet. By then the Englishmen had exhausted practically all their ammunition, so Simon wisely surrendered his tiny command. Eight survivors were taken captive, including the five wounded. It was 3:45 pm.

Skirmish at Col de Bonne Nouvelle

While all this occurred, Brigadier Festing remained stymied before the Col de Bonne Nouvelle. Initially, he had ordered Lt. Col. Hugh Stockwell’s 2nd Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers to clear the heights in conjunction with Simon’s original sortie, but the tanks had moved on. That was a mistake.

Two companies advanced with fixed bayonets, supported by a pair of light howitzers of 455 Battery. The French were waiting. At once heavy machine-gun and rifle fire swept the field, and men began to fall. Apparently, after Simon’s tanks had departed the Tirailleurs simply closed ranks and braced for the next assault. Now Welshmen were dying in the sun-scorched scrub. Officers took control and men rushed forward—fire and movement—getting so close that enemy riflemen had little trouble picking their targets.

A captain was killed at nearly point-blank range then was promptly avenged by his pistol-wielding lieutenant. Bayonets flashed, and by 3 pm the ridge was in British hands—but not without cost. Three officers and many others had been killed with numerous wounded. Drained by debilitating heat, the strenuous march, and the strain of battle, Welshmen collapsed among the boulders while Lt. Col. J.F. Armstrong’s 1st Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers resumed the advance. By then, the balance of B Special Service Squadron, led by Captain Peter Palmer, had arrived, minus one Tetrarch abandoned at the beach due to electrical problems.

The skirmish at the Col de Bonne Nouvelle had clearly been unexpected. What Brigadier Festing did not know was that the Vichy naval officer he had released earlier had, instead of urging his commanders’ surrender, sounded the alarm and the French quickly forwarded reinforcements piecemeal to hold the pass until the Joffre Line could be fully manned. Having accomplished their mission, the delaying force withdrew.

Astles’s Reconnaissance

Throughout the action Festing had been acutely aware of an intense exchange of gunfire farther beyond the ridge and assumed that Simon’s tanks were clearing the way to Antsirane. But just as the Welshmen had achieved success Lieutenant Astles’s Tetrarch came tearing from the east at top speed with a Vichy motorcycle and sidecar trailing beneath the muzzle of a crewman’s machine gun—the only survivors of yet another encounter with Vichy reinforcements motoring forward. Festing listened intently to Astles’s disturbing report. Anxious to take Antsirane before dark, the brigadier ordered Captain Palmer’s freshly arrived tanks to proceed posthaste to reconnoiter the heretofore unknown enemy defenses. Armstrong’s Scots Fusiliers would follow as rapidly as possible. It was mid-afternoon.

Four Valentines and three Tetrarchs thundered down the road, one being that of the indomitable Astles. They had barely commenced their reconnaissance when shells began bursting all about. Not wanting to repeat Simon’s folly, Palmer ordered his column to break right into the tall scrub of a nearby cane plantation, hoping to find good hull-down positions from which they could observe the front. Fully manned, the Joffre Line remained invisible, shrouded by vegetation. As a consequence, Palmer ordered Sgt. Maj. Allen’s Valentine to follow his own in an attempt to draw fire. It worked far too well.

No sooner had the pair exposed themselves than both were hit. A track of Allen’s tank snapped and snaked off its sprocket. Then another round clanged off the turret, wounding all inside while rendering their gun inoperable. Their vehicle useless, Allen ordered everyone out. Only two staggered safely away.

Palmer’s crew fared no better. Several solid hits wounded him and his driver but left the gunner intact. They too bailed to join Allen’s men, but just then Palmer noticed Allen’s driver flailing helplessly in his hatch and backtracked to pull him free. Now clear, both limped away only to vanish in the blinding flash of a shattering explosion.

By then the others had located the source of their comrades’ demise and cut loose with their two-pounders, sending shell after shell into a low ridge some 1,800 yards distant and to the right. It was Fort Bellevue, the sturdy redoubt that anchored the enemy’s eastern flank. Vichy gunners responded with a vengeance, and as twilight loomed the armor fell back. It was barely 6 pm. In the course of three short encounters, B Special Service Squadron had lost half its tank strength as well as 17 of its 45 men, six of them killed.

Also retiring were elements of the Scots Fusiliers, who had faced the same galling fire after launching a minor attack on the left. For the British, the day ended with flagging spirits; for the French, burgeoning confidence.

Frontline Frankie’s Attack on the Joffre Line

The only bright spot was the achievements of William Sanguinett’s command, which, after striking out from Windsor Castle, had trekked the Andrakaka Peninsula without incident until coming upon a stubborn roadblock halfway through. A sharp firefight dislodged the defenders who left 50 wounded behind, and the march resumed nearly unimpeded. By mid-afternoon the commandos were in possession of Diego Suarez.

But Brigadier Festing knew nothing of this. Meanwhile, he had advanced his headquarters to a small hotel in the village of La Scama, well within sniper range. It was a bold move, but Festing, revered as “Frontline Frankie,” wanted to personally observe the action. By then Lt. Col. J.R. Thatcher’s 2nd Battalion, East Lancashire Regiment had joined Armstrong’s 1st Battalion, Scots Fusiliers at the front while the exhausted Welshmen dodged bullets at brigade headquarters. Festing’s last battalion, Lt. Col. Michael West’s 2nd Battalion, South Lancashire Regiment was still tramping from the beaches but was expected to arrive before dark.

Festing scrutinized the Joffre Line about 1,200 yards to his front, noting its perfect placement on a gently rising ridge that spanned an isthmus separating two bays. He could judge its width as perhaps 2,000 yards and had already felt the sting of its weapons but had yet to test the strength of its well-concealed trenches and fortifications that commanded open, slightly undulating terrain. Acknowledging its advantages, Festing made preparations for an all-out attack, confident he would be in Antsirane by the next day.

Festing’s plan called for West’s South Lancashires to penetrate the mangrove of the eastern shore to outflank and attack Fort Bellevue from the rear just as two other battalions launched frontal assaults at dawn. Preliminary air strikes were to bomb the Vichy line while four 3.7-inch howitzers and two 25-pounders of 455 Battery provided support. West’s battalion would jump off at 2 am to allow time to get into place.

Divided into three columns, West’s 500-strong command departed on schedule and was quickly swallowed by the fetid, mosquito-plagued swamp. In time, the combination of darkness and tangled vegetation so hampered progress that each column became disjointed, then splintered. To make matters worse, every wireless set malfunctioned and communications with brigade headquarters were lost. West realized he would never be able to maintain his projected timetable.

Back at the front, the assault companies of the 1st Battalion, Scots Fusiliers on the right and the 2nd Battalion, East Lancashire on the left slipped forward under darkness in preparation for the attack. Some managed to bypass an unfinished antitank ditch and hunkered uneasily several hundred yards before the enemy trenches.

An Immediate Disaster

At precisely 5 am, fleet aircraft gave the Joffre Line a severe drubbing but did little damage. Thirty minutes later the infantry rose and traversed the open ground as swiftly as possible until staggered by a perfect storm of iron and steel. Shrapnel cascaded with astonishing regularity as the French 75mm guns flaunted their reputation for rapid, accurate fire while machine guns flailed the plain. And then the mortar shells began to fall.

The assault companies were being shot to pieces, trapped between the strong defensive positions to their front and the antitank ditches to their rear. Unable to advance, dozens of Scots and Englishmen sought shelter in the depths of the tank traps. Those caught in the open scampered for shell holes or depressions where many remained until dark. The antitank ditches were nearly seven feet deep with steep banks, and it became obvious that they too were death traps. To stay invited bombardment by mortars, while every attempt to escape over the rear wall was met with murderous gunfire.

Disaster compounded disaster. The six guns of 455 Battery barked in continuous support until counterbattery fire struck, wounding many, forcing the guns to retire. A mortar detachment of the Scots Fusiliers worked to within a couple hundred yards of their comrades trapped at the front and popped shell after shell into the French line. After exhausting much of their ammunition, 2nd Lieutenant Powrie was killed while attempting to bring up additional rounds.

One company of East Lancashires advanced over the barren plain and was eviscerated by machine guns and 75s. In Lieutenant Wood’s platoon, one shell took out five men at once, one severely when shrapnel struck a grenade that exploded while still in its pouch. Five of eight of their supporting Bren carriers were knocked out one after another, compelling the final three to pull back. The cry, “Stretcher bearer!” rang out all across the front. Within an hour of its commencement, the attack was cancelled.

Less than half the men returned to their original lines. Many were stranded in the field or squatted in the tank ditches, unable to move. How many were unscathed was anyone’s guess. To add to the confusion the dry scrub had been ignited by the fierce artillery exchange and now brushfires swept the plain, forcing many Britons into ignominious flight. Mortified officers corralled the culprits and led them back to the front once the fires had passed. It was not a glorious day for the British Army.

Heroism in Defeat

Still, there were episodes of British gallantry. After Corporal Bell’s section of Scots Fusiliers had scrambled into an antitank ditch, a grenade tumbled in and settled between him and Fusilier Bunyan. Bunyan shouted, “Look out, boys!” as he grabbed the bomb, just in time to absorb its fatal blast, saving his mates.

Second Lieutenant Peter Reynier of the same battalion also displayed exemplary courage when his platoon was pinned down by heavy machine-gun fire emanating from a distant pillbox. Clutching several grenades, Reynier bellied to within 60 feet of the still hammering gun when a lookout spotted him and opened fire. The first round shattered the lieutenant’s jaw. Reynier sprang up and charged. Another bullet ripped his left arm, but not before his right reared back to hurl a grenade directly into a firing slit.

Unknown to Reynier, each aperture had been screened with wire mesh to prevent just such an event and the bomb came bounding back with Reynier receiving much of the blast. Bleeding profusely, the lieutenant lay unattended until finally taken captive.

Guerrillas Behind Enemy Lines

Brigadier Festing fumed as his plan unraveled. Much of his brigade lay scattered between La Scama and the Joffre Line with little hope of regaining British lines. The balance had returned battered and demoralized. The exact location of the enemy’s fortifications still remained a mystery, and he had no idea what had happened to Colonel West’s flanking maneuver. Due to the malfunction of the 2nd South Lancashires’ radios, Festing presumed the entire command had been killed or captured—another devastating blow.

At 7 am, General Sturges stormed into Festing’s headquarters and was not pleased. After surveying the damages he decided a night assault by Brigadier G.W.B. Tarleton’s fresh 17th Brigade, supported by Festing’s decimated command, would carry the works. Tarleton’s brigade had just completed landing but was expected to arrive by evening. As an added measure Sturges planned for Sanguinetti’s commandos to make a diversionary cross-bay assault, providing they could find boats at Diego Suarez. After issuing the appropriate orders, Sturges rushed back to confer with Admiral Syfret regarding his plan. While retracing his route he was encouraged by the sight of Tarleton’s battalions marching confidently forward as bagpipers lent a lively tune.

That afternoon Festing’s headquarters was electrified when Colonel West of the lost South Lancashire battalion came swaggering in with a Thompson submachine gun tucked beneath an arm. His adoring entourage boasted that their swashbuckling commander had personally accounted for as many as 35 Vichy in the course of their adventure. West’s report offered a glimmer of hope. While most of Festing’s men had not completed their mission—in fact the entire left wing had been stopped short of Fort Bellevue—others had persevered.

Prior to his battalion’s departure West had anticipated its disintegration in the dark and inhospitable swamp and had issued a precautionary order that if separated his subordinates were to form guerrilla parties and carry on, striking targets of opportunity at their discretion. That is exactly what happened. Once organization had collapsed, West ordered Major Northcott to gather those he could to carry out the provisional order while he returned to advise headquarters of the situation. West’s report proved to be the only good news of an otherwise dismal day. Festing hoped that Northcott’s forlorn hope would prove beneficial to the operation’s outcome.

Beneficial it was. Upon clearing the mangrove, Major Northcott organized small raiding parties that went to work with boundless zeal. Telephone lines were cut. One group attacked a Vichy artillery train and scattered the battery’s pack animals. Others sniped at the Joffre Line from the rear while vehicles rushing to and from the front were ambushed by jubilant Britons. Northcott’s raiders were causing a great deal of anxiety among the French.

Two Setbacks For the British

Meanwhile, Sturges was again aboard Ramillies, where he disclosed his plan to Admiral Syfret, proposing a revision that required naval assistance. If a fast destroyer could round Cape Amber and force the harbor entrance, a contingent of Royal Marines could land at Antsirane simultaneous to Sanguinetti’s diversionary assault, thereby drawing forces from the Joffre Line. It was a risky proposition considering the harbor’s narrow entrance and strong defenses, but Syfret agreed although he only gave the venture a minimal chance of success. At once 50 marines were transferred from Ramillies to the destroyer HMS Anthony, which promptly departed to cover the 120 miles to Antsirane. Zero Hour was set at 8:30 pm.

While the commanders schemed, two more problems arose. First, the LST Bachaquero, carrying a dozen desperately needed 25-pounders of 9th Field Regiment, was unable to beach at Ambararata Bay on D-day and was diverted north to Courrier, arriving late that afternoon. Eventually one battery was muscled ashore. In the waning light, the men could not find the Antsirane road and were rerouted to Diego Suarez with orders to bombard the Joffre Line from the rear. Arriving the following day, the gunners were shelled by the elusive gunboat D’Entrecasteaux, which was eventually sunk with the assistance of naval gunnery and fleet aircraft. Now free from harassment, the gunners resumed their mission, but lacking proper observation fired blindly across the bay.

The other setback came when No. 5 Commando failed to secure boats to launch their diversionary attack from Diego Suarez. Unable to contribute to the final assault, they remained idle on the northern shore.

Sturges Orders Another Attack

Back at La Scama, darkness had fallen. The scouring fires had passed. Smudge-faced soldiers nursed billy pots as they brewed their evening tea and stared slack-jawed into the cheerless night. Many comrades remained trapped in no-man’s land, where patrols probed the smoldering plain for fissures in the Joffre Line but found none. Meanwhile, Brigadier Tarleton’s 17th Brigade staggered in, having endured stifling heat, brush fires, and sporadic sniping as they trudged the sandy track.

By then General Sturges’s attack orders had arrived at the appropriate brigade headquarters. Tarleton decided to lead with Lt. Col. John W. Hinchcliffe’s 2nd Battalion, The Northamptonshire Regiment on the right while Lt. Col. George Rawstorne’s understrength 6th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders advanced to their left, assisted by an attached company of the 2nd Welsh Fusiliers. Lt. Col. I.D. Macinnes’s 2nd Battalion Scots Fusiliers, sister battalion of Armstrong’s decimated 1st Battalion, would follow.

The assault would be supported by what remained of Festing’s 29th Brigade with orders to be in Antsirane by daybreak. Thankfully, an additional battery of 25-pounders was now in action, having been offloaded piecemeal from transports at Blue Beach and rushed to the front.

“Caber Feidh!”

At 8:30 pm, the Seaforths and Northamptons advanced with leveled bayonets. The impetus of the attack was directed at the enemy’s center between Forts Caimans and Bellevue, using the central road as a guide. Having witnessed the carnage of the previous attacks, no one held misconceptions of an easy victory, but with spirits bolstered by a liberal rum ration and the issuance of stimulating Benzedrine tablets, no one faltered either.

The British reached halfway across without a shot being fired. The fortunes of war had finally turned in their favor, partly due to the darkness, but also to a sense of overconfidence among the defenders, whose officers had convinced them that they were winning. As a result, many Vichy soldiers had dropped their guard, believing the enemy would not strike again until daylight.

As the khaki line drew nearer, a vigilant African sounded the alarm. Senegalese and Malagasy soldiers sprang to arms and opened fire, but too late. Their Scots blood up, the Seaforths roared their war cry, “Caber Feidh!” as they leaped into the trenches and went to work with the bayonet. One sergeant came face to face with an enraged Senegalese and lunged with such force that his bayonet ran clear through him.

Bren gunners released a galling fire, ripping men apart at point-blank range, but the Africans responded with unrestrained savagery. Blades flashed. Shots rang out. One highlander staggered away, his arm a bloody stump. African and Briton grappled in intimate desperation and rolled upon the earthen floor. A shower of grenades added to the confusion while Vichy mortar bombs plunked steadily among attacker and defender alike.

In the center, a company of Malagasy led by Commander Fontaine struggled to hold the line, but when Fontaine fell mortally wounded his ill-trained troops lost all motivation and abandoned their positions as the British stormed through. Once breached, the line began to crumble, and by 11 pm all assault elements had reached their designated objectives some 1,800 yards beyond the trenches. Signal flares arched into the darkness to announce both battalions’ success. They had breached the Joffre Line. Immediately, Tarleton shoved his reserves through the gap followed by Festing’s battered brigade. Antsirane was now but a short march away.

HMS Anthony‘s Fight to the Shore

While the Seaforths and Northamptons were engaged at the Joffre Line, HMS Anthony had achieved the near impossible. Shortly after 8 pm she plowed full speed through the narrow strait, provoking the wrath of the protective batteries. Shells splashed to the fore, aft, starboard, and port as Anthony pressed on with all guns blazing. A garish beam lashed from the shore and fastened onto Anthony with unshakable tenacity until extinguished by the second salvo from HMS Devonshire, which had joined Hermione as offshore support. Once again cloaked in darkness, Anthony raced for Antsirane, nearly eight miles away.

Within 20 minutes she reached her destination. Lt. Cmdr. John Hodges, Anthony’s skipper, wanted to land his marines on Antsirane’s docks, now shrouded by smoke and flame from earlier airstrikes. As his vessel edged closer the shoreline erupted with raucous gunfire. Navy gunners leveled their pompoms and 20mm automatic Oerlikons and unleashed a devastating response until the incoming fire ceased.

Blinded by billowing smoke, Anthony came in hard but missed the quay, then missed again when strong winds intervened. Unshaken, Hodges simply threw Anthony’s engines into reverse and whipped her stern athwart and kept her pressed firmly against the jetty until all 50 marines had scrambled over her side. But even this maneuver was not without peril. Again machine guns raked the deck while a 75mm gun was shouldered into place and opened fire. Sailors ducked, believing in miracles as the round shrieked harmlessly overhead. A second shot was denied when marines rushed the gun and scattered its crew into the night.

Her duty done, Anthony shoved off and once more ran the gauntlet before regaining the open sea, exchanging fire all the way. It was a breathtaking adventure for all involved—one no one wished to repeat.

Taking the Governor’s House

Once ashore, the marines quickly realized that the commandos were conspicuously absent —they were on their own. Under the direction of Captain Martin Price, they entered the town spraying bullets and flinging grenades in every direction. An artillery headquarters was overwhelmed. Then a number of fires were set, creating such confusion and commotion that the French believed that a much larger force had indeed been landed. The blitz continued unabated until stopped by a fusillade of small arms fire originating from a naval barracks. Several marines edged forward and tossed grenades through windows, compelling the occupants to come out with hands up.

A squad rushed in to ensure the building was vacant only to discover a number of British soldiers captured in earlier actions. After securing enemy weapons, these men were integrated into the ranks. But Captain Price now faced a conundrum. Even with the addition of the liberated prisoners, his meager force was experiencing great difficulty keeping tabs on its numerically superior Vichy captives. As a result, Price suspended his rampage and formed a defensive perimeter near the dockyards to await Sturges’s columns. Throughout the night the marines monitored the distant battle sounds and wondered when relief would arrive, if at all.

While Price laagered at the docks, events accelerated at the Joffre Line. The balance of Tarleton’s 17th Brigade as well as Festing’s 29th Independent Brigade passed through the victorious Seaforths and Northamptons and pushed on toward Antsirane. Both brigades entered town practically unopposed and scoured the streets of what little resistance remained and at little cost. Shortly after midnight the eerie wail of bagpipes pierced the darkness as both Scots Fusilier battalions closed in on the Governor’s House, convincing a few frightened Malagasy to emerge with hands held high. Governor General Annett was not present.

Two Days of Intense Combat

An hour later, elements of the Welsh Fusiliers entered the Defense Headquarters and rousted Colonel Pierre Clarebout and Captain Paul Maerten, the ranking Vichy army and navy commanders, and marched them out at gunpoint. About the same time, a hearty cheer was heard from the dockyards where other Welshmen completed the link with Captain Price’s marines. For all practical purposes Antsirane was now in British hands and the battle all but over.

At daybreak, General Sturges entered town and negotiated a cease-fire with Colonel Clarebout and Captain Maerten, which ultimately induced the surrender of Forts Caimans and Bellevue as well as the coastal batteries that studded the Orangea Peninsula. By then, 13th Brigade had arrived to assist with the consolidation. With the big guns negated, the fleet entered the harbor and the following morning Admiral Syfret accepted the surrender of all Vichy forces in Northern Madagascar. Diego Suarez was finally under Allied control.

From the outset it was hoped that Operation Ironclad could be accomplished easily and with minimal casualties. Instead, it had taken three days—two of them devoted to intense combat in which 105 British soldiers lost their lives and 284 others were wounded, plus four missing in action. The Vichy forces also suffered. Of the estimated 4,000 defenders, 145 were reported killed and 336 wounded.

A Second Campaign in Madagascar

For all intents and purposes, this concluded Operation Ironclad. The 13th and 17th Brigades soon departed for India to join their parent 5th Division. Meanwhile, Governor General Annet remained loyal to the Vichy government and vowed continued opposition from the island’s rugged interior. As a result, another campaign was launched that September, culminating two months later with Annet’s ultimate surrender. Overall, both campaigns had cost British and Commonwealth forces 135 battle deaths and 394 wounded, not to mention those missing or the many who succumbed to tropical diseases.

In the end, Operation Ironclad, the first major British amphibious undertaking since Gallipoli, proved to be for naught. The perceived threat of Japanese occupation proved to be hollow. They had never intended to occupy Diego Suarez. But in the spring of 1942, the threat seemed genuine to beleaguered Britain and the operation justified. To do nothing seemed suicidal.

Madagascar was among the final battles of an undeclared war between Great Britain and Vichy France. The British fought with their customary doggedness, the French with valor and determination. In time, the entire campaign became a footnote, then a fading memory, and finally committed to obscurity. Who remembers Madagascar?

Good morning

I know my dear father (Captain Frank William Cooper RAMC) was in this campaign having previously been in in Tanganyika, Kenya and Uganda, where he returned to spend the remainder of the war as a senior pharmacist. He frequently spoke of his time in Madagascar and just how careful they all had to be because of the Vichy French. He fell in love with Diego Suarez and my wife and I were fortunate enough to visit it a few years ago and could fully understand his love of this beautiful island. We found the people to be charming and welcoming and the work some are now doing in relation to conservation of the forests and the magical lemurs is terrific. If anyone knows anything about the medical side of the history of WW2 in Madagascar I would love to hear from them.

After the way my father came back to the UK for a short while before heading back to East Africa, where he worked as chief pharmacist for the Overseas Food Corporation and the ill-fated ground nut scheme. Our family came home in 1953 when I was in a carrycot. My father loved Africa and even more, loved the Africans – he was never happier than spending time on a Saturday evening in their huts having a couple of beers and singing with them. He always told me they were ‘real people’ not affected by material possessions and wealth. When my wife and I have been back we obviously only got a glimpse, but could see what he meant.

Could you please include the rest of the ship in the picture at the top of the page? I’m interested to know what ship it is.

Thank you.

My father William Slack was on board HMS ANTHONY He told me the fleet lined up and ANTHONY sailed between the ships and got a three cheers from the crews – also the captain of ANTHONY got a medal my dad got a letter I think as well He hardly ever spoke about his exploits in ww2 – including being at sea and chasing BISMARK !!

The map maker has incorrectly named the Royal Sussex Fusiliers as one of the initial assault units instead of the 1st Bn., Royal Scots Fusiliers.

HMS Ramillies, pictured in the frontipiece puoo, later served in off shore gunfire support inOperation Overlord Off Normandy as well as Operation Dragoon, off Southern France, two years after Ironclad.