By Robert L. Swain

Young and ambitious, recently crowned English king Henry V had a dynastic point to make, one that would relieve him of the taint of royal illegitimacy born of the fact that his father had usurped the English throne a mere decade before. Only two years after ascending the throne, Henry intended to exploit the popular appeal of carrying battle to an enemy’s territory, with all its attendant opportunities for plunder, glory, and tangible signs of God’s favor. English kings had played the war card frequently in the seemingly endless Hundred Years’ War. Hoping to demonstrate God’s blessing on him on the field of battle, Henry was determined to reassert the longstanding English claim to the French throne that had ignited the original conflict with their Valois cousins in France decades earlier.

Well-tutored for the role of king, Henry was given his first meaningful responsibility at the age of 12, when he was created Prince of Wales by his father, King Henry IV. His first battle command followed three years later in Wales, earning him a slight wound. At the Battle of Shrewsbury in 1403, he helped his father beat back a determined revolt led by Lord Henry Percy (Shakespeare’s famous Hotspur), and at the very outset of his reign he had suppressed a revolt at home by Lollard religious fanatics. Now, at age 27, Henry was focusing his considerable organizational skills on developing and equipping an invasion plan that would culminate in a formal declaration of war against the French after a suitable but brief period of sham diplomacy. Henry’s ambitious plan came together in the first week of July 1415.

Henry’s Invasion Fleet Gathers at Southampton

At the port of Southampton, Henry assembled 2,000 men-at-arms, supported by engineers, carpenters, masons, armorers, smiths, cooks, minstrels, chaplains and nearly 8,000 archers. Henry’s younger brother Thomas, the Duke of Clarence, mustered an additional 240 knights and over 700 archers in a show of familial support, while the graybearded Duke of York, a cousin, arrived with 100 men-at-arms and 300 archers in his charge. Because of their rank, Clarence and York were obliged also to bring 50 horses each. In addition to these peers of the realm, Henry was joined by Lords Salisbury and Warwick and Sir John Holland, all of whom had campaigned with him previously in Wales.

The king’s invasion fleet, gathered over a period of four months, totaled some 1,500 sturdy cogs, along with a number of impressed foreign galleys seized in English ports and impressed into service with their crews. The assortment of ships filled Southampton harbor and the surrounding waters and ports, as Henry turned to the task of boarding troops, horses, and war materiel, which included siege engines, gunpowder, stone shot, cannon, bow staves, and mining tools. Mounds of foodstuffs included ample quantities of bread, dried fish, salted meat, flour and beer as well as cattle, sheep, and pigs for fresh meat. Chaotic at times, the many horses were the most difficult to board, and it took nearly a month before the army was able to set sail for France in the early afternoon of Sunday, August 11. Leaving his brother John, Duke of Bedford, as regent during his absence, Henry led the way on his flagship the Trinity Royal. Forty-eight hours later the fleet reached the Seine estuary and anchored three miles from the port town of Harfleur, which had been selected as the army’s base of operations because it was at the end of the shortest possible sea-route back to England. After securing his entry point, Henry would prove his divine support by crossing swords with French men-at-arms.

It was a propitious time to try the French. Their monarch, Charles VI, was a weak-minded, rather wishy-washy ruler given to frequent fits of insanity. In the power vacuum surrounding the lunatic king, French nobles had divided along two main party lines: the Armagnacs and the Burgundians. The Duke of Orleans led the Armagnacs, while the Burgundians were headed by John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy, whose ferocious reputation justified his nickname. Making matters worse, the Burgundians had allied themselves with the English. The grand seigneurs hated each other more than they hated the English, who could at least be counted on to leave France after a short incursion. The palace intrigue, by contrast, would go on indefinitely.

The Seige of Harfleur

Unopposed, the English army finished disembarking on August 15 and completed its encirclement of Harfleur, well-defended with a thick outer wall two and a half miles around and studded with 26 towers. Undaunted, Henry brazenly called for the garrison’s surrender the very next day, but the French scoffed at Henry’s herald. Henry responded by enclosing the town with a stockade, making it almost impossible for any of the French garrison to get in or out, and implemented a determined siege. What followed was debilitating for both sides, who suffered terribly from hunger, disease and frequently scheduled skirmishes and shelling. The initial attempts by the English to breach Harfleur’s defenses were met by torrential buckets of boiling water, quicklime and sulfur poured down on their lowered heads from the French ramparts. Subsequent attempts to undermine the walls were repulsed by French countermines. Still, Henry was determined to subdue the town, viewing it as the key to all of Normandy. He personally supervised thrice-daily bombardments of the town.

By the third week of September, the battered French garrison was reduced to near starvation, and a contingent of town leaders surrendered to Henry, who was able to celebrate his 28th birthday along with this victory. However, an alarming number of Englishmen were sick with malaria and dysentery, the dreaded “bloody flux,” offsetting the military success and diminishing the birthday festivities. As many as a third of Henry’s army would die of the illnesses, induced by a combination of unusually hot weather and dank marsh air filled with flies and mosquitoes, indigestible cockles and mussels, bad wine, and unripe fruit. Among the seriously ill were two earls and the young bishop of Norwich; all three would die within days. Alarmed over the growing number of sick, Henry evacuated nearly 2,000 of his army back to England. Among those invalided home were the Duke of Clarence, the Duke of Norfolk, and the Earl of March.

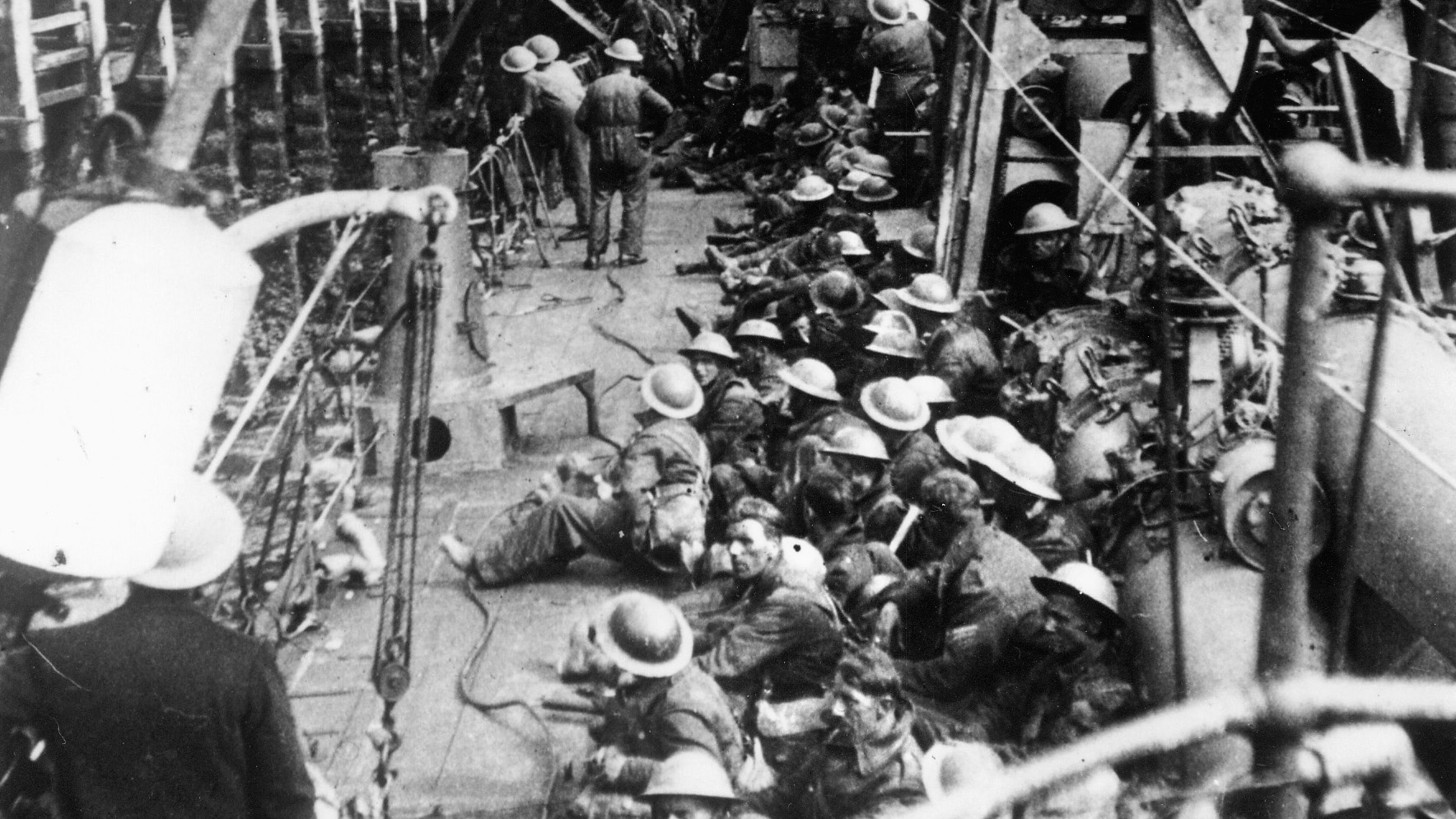

Ship captains reboarded the most seriously ill English soldiers, along with some of the richest citizens of Harfleur, who would be were held for safekeeping in England until ransomed. In the ensuing passage home, the ships were fouled so badly by the sick that few of the vessels could be used again. Abandoning the worst of them in English ports, the captains leased other ships at considerable expense to the king’s council in London, quickly acquired fresh supplies, and were back at Harfleur by the last day of September.

Henry Marches into the Countryside

In the meantime, Henry’s remaining army recovered as best it could at Harfleur, while the king reassessed the situation. Rainstorms sweeping in from the sea were making the surrounding countryside difficult to traverse. The bad weather, combined with the reduction of his army to roughly 900 men-at-arms and 6,000 archers, threw into serious doubt Henry’s long-held ambition to conquer Paris. The young king’s choices seemed severely limited—either withdraw (which Henry thought smacked of retreat), or call for reinforcements to march through Normandy to Calais, an English-held stronghold from which they could depart honorably for home. A majority of the war council thought that such a march through French territory was a foolish idea, but a number of the just-returned ship captains, including 29-year-old Robert Howard of East Anglia, a friend of Henry’s youth, offered the king a portion of their healthy crews to buttress his diminished army.

Encouraged by the unexpected support and determined to demonstrate his ability to proceed through a hostile countryside under divine protection, Henry overruled his war council and marched out of Harfleur on October 6 with 900 men-at-arms and 5,000 archers in middling condition, heading for Calais (England’s continental base won by Edward III in 1347) 160 miles away. Left in command of the 1,200-man Harfleur garrison was Henry’s uncle, Thomas Beaufort, Earl of Dorset, who would later be rewarded with a dukedom for carrying out this comparatively unchallenging role. With no cannon and few carts to encumber him, Henry hoped to achieve a credible “test of arms” with the French somewhere along the way to Calais before exiting Normandy. He expected the march to take eight days, and only carried sufficient food on his packhorses to last that long. The arithmetic was simple. To reach Calais, the army had to make at least 20 miles a day with limited foraging in a period when one could expect daily autumnal rains.

Henry’s advance guard was under the command of Sir John Cornwall, while the redoubtable Henry and his brother, the Duke of Gloucester, led the main force (with Henry keeping an eye on his somewhat impulsive sibling). The Duke of York and the Earl of Oxford commanded the rear guard. Henry’s plan was to march northeast to the Somme River and then southeast along its bank until he reached the ford of Blanchetaque, where Edward had crossed before winning his signal victory at Crécy seven decades earlier. Once safely across the river, Henry would head north toward Calais. To ensure a safe crossing, he sent word for a force from Calais to secure the ford before he arrived. Even with a healthy army and perfect weather, Henry’s plan would have been risky. As if to prove that point, he and his men managed to cover only 80 miles in the first five days, 20 less than intended. Despite this shortfall, the intrepid English had managed to cross two rivers in five days and the next river, the Somme, was only 13 miles away.

As Henry marched on, he was unaware that a force under French Marshal Boucicaut was shadowing him. Instead, he kept a keen eye on the behavior of his army around churches and shrines the army might pass, well aware of the importance of staying on favorable terms with his divine sponsor. Told of a soldier caught stealing a cheap copper box from a nearby church, Henry stopped the advance long enough to stage a hanging (commemorated by the execution of Falstaff’s old friend Bardolph in Shakespeare’s Henry V.) Sobered by this display, the army bedded down that night in the open, nobles and commoners alike wrapped in their soggy cloaks in a more or less futile effort to stay warm.

Stymied by the Somme

The army finally reached the Somme on October 12, only to discover that the causeway there had been destroyed and a sizable contingent under Marshal Boucicaut was patrolling on the opposite side. The expected English force from Calais had been intercepted and driven off. Sobered by the sight of so many French men-at-arms and rapidly running out of provisions, Henry turned eastward to find another intact crossing, while seeking to avoid a military confrontation. The army, although disappointed, trudged ahead along the river to reach a point opposite Abbeville on October 15. They were now 60 miles south of Calais.

Although the Abbeville causeway was still intact, Henry and his men did not cross there. Still blocking them on the other side was a new (or possibly the same) French force. Instead of challenging them, Henry elected to push southeast to Pont Remy, but he found no safe crossing there either. To compound his difficulties, food was running short and the nights were turning noticeably colder. Just as ominously, dwellings and farms along the way were barred and silent; as stragglers fell behind they were set on and killed by the furious locals. Others, made weak by dysentery, collapsed by the side of the road and were left to fend for themselves.

As every invading English army before them had done in France, those of Henry’s men who still well enough to swing a sword began to loot and kill their way across the countryside. Columns of black smoke marked their route. When some nobles worried that this would provoke reprisals, Henry’s response was bluntly simple: “War without fire is like sausages without mustard.” Given the freedom to do what they liked, the Englishmen foraged, plundered, raped and torched the countryside to their hearts’ content. Approaching Boves, Henry sent word ahead that he would sack the town if provisions were not offered and delivered to his army. The inhabitants were suitably intimidated and came forth with sufficient quantities of bread and wine in exchange for the English sparing their town. With everyone’s hunger abated for the moment, the weary commanders and their men listened attentively to Henry’s announcement that they would cross the Somme at the next shallow point they encountered, come what may.

As promised, Henry got all his men across the Somme just before nightfall on October 19, crossing a pair of unguarded causeways at Bethencourt and Voyennes. Sir John Cornwall had crossed first with 500 men-at-arms to hold the other side against a French counterattack, which followed shortly but was turned back. Relieved, Henry promised his men that no other natural barriers remained between them and the safety of Calais, he failed to add that the safe-haven port was now more than 100 miles away. Anxious to be underway, Henry ordered his men to push on despite a heavy rain that was playing havoc with everyone’s footwear. Nonetheless, the army achieved the remarkable pace of 16 miles the first day and 18 the next.

Marching into a Trap?

On their third day beyond the Somme, scouts who had fanned out ahead of the army returned to Henry with the unwelcome word that “many thousands of the enemy” were drawing close to their position and, even worse, appeared to be firmly astride the route to Calais. Unknown to Henry, the French had been roughly paralleling their line of march ever since they had crossed the Somme. Now they were only six miles away. Henry and his commanders reluctantly agreed that some sort of battle was virtually inevitable.

At dawn’s light on October 23, scouts sighted through the drizzling rain a French force just ahead. Alerted, Henry rode forward to see for himself and was startled by the overwhelming number of French knights, visible in the distance. Suddenly apprehensive, Henry returned to his camp and convened a war council in which he warned his commanders just how outnumbered they appeared to be. They discussed getting around the enemy, which seemed unlikely; going back the way they had come, or negotiating a truce. Clearly shaken, Henry interrupted the council to send word to the French that he was willing to sue for peace, offering to surrender Harfleur and pay for the damages he and his men had done since then in exchange for safe passage to Calais. When Henry’s offer was relayed to the French commanders, they listened amusedly and rejected it before Henry had even ended his council.

When the French response reached Henry, he realized more than ever that they were prepared to fight him wherever and whenever he wished. Although seemingly caught in a trap of his own making, Henry sent back a bold reply, saying that although he did not seek a battle, he intended to proceed toward Calais. If the French impeded his way, it would be at their own peril. The French commanders, possibly reasoning that they could starve Henry’s army into submission, withdrew. When Henry continued his march toward Calais the next morning in heavy rain, the English were surprised to discover no French troops in front of them. Their elation was short-lived, however—several miles farther north they saw unmistakable evidence that thousands of horses and men had torn up the fields ahead of them. Shaken by this, the English continued marching north for another three days without sighting any French troops. But on the morning of October 24, Henry’s scouts reached a ridge at Blangy and saw a massive French army moving across the road ahead, once again blocking the route to Calais. Certain that a confrontation was at hand, Henry prepared to give battle with an army reduced to 800 men-at-arms and fewer than 5,000 archers.

More disturbing to Henry than the reduced number of his men-at-arms was their physical condition. All were tired and hungry, and some still suffered from dysentery. They had come 260 miles in three weeks’ time, with only one day’s solid rest, and their endurance was slipping badly. Many were barefoot, all were bedraggled. The weather had been bad for days—everyone was wet through and through. What bread they still had in their packs had disintegrated into a pulpy mess. It was a distinctly unimposing force.

While the English camp was subdued, the French were positively giddy in anticipation of the coming battle. Indeed, they were so confident of victory that they laughed about parading a captured Henry through the streets of Paris in a painted cart, while 12 knights found time to have a solemn ceremony in which they swore to each other that one of them would either capture or kill Henry in the coming battle or else perish in the attempt. Everyone seemed to believe that the ragged English force would be so easily vanquished that the only question was whether everyone would have time to get into the fight before it was over. For the balance of the day, the two sides stayed where they were, preparing for battle. Men-at-arms attended to their weapons, while English longbowmen and French archers checked the condition of their bows and crossbows and supplies of arrows. As daylight faded, attempts were made to sleep despite the rotten weather. Henry, unlike Shakespeare’s depiction of him in Henry V, probably did not pass among the men during the night, making stirring speeches. He would have been too busy planning for the next day’s battle.

Lining Up for Battle

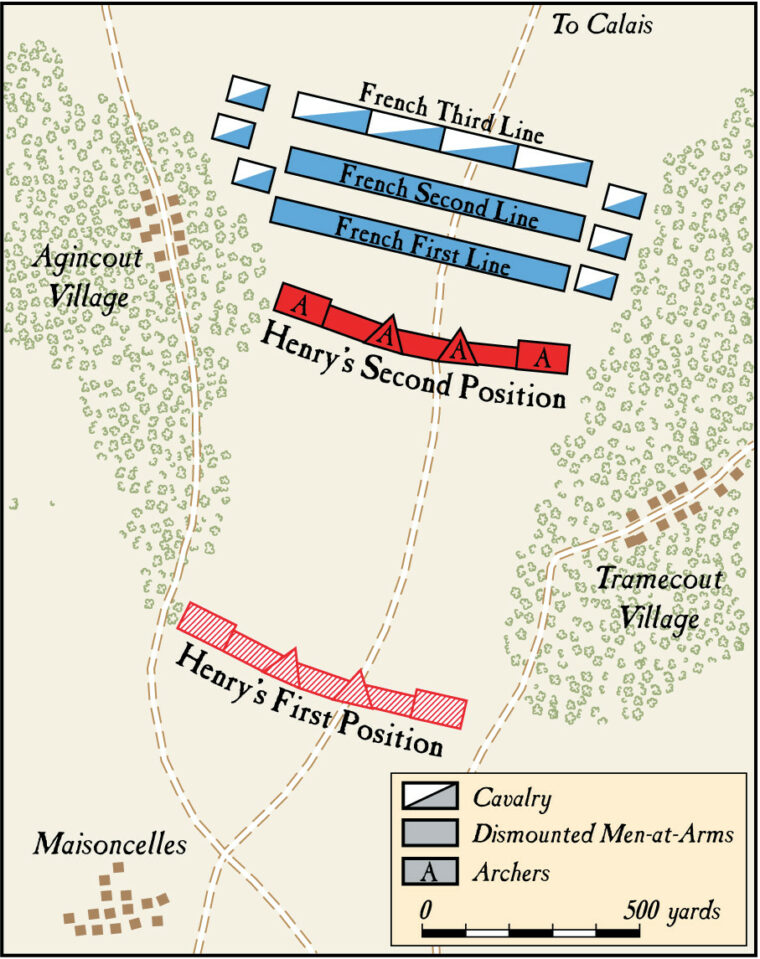

After a restless night, the English were up early, walking about to shake off their stiffness and complaining of the chill in the air. Knights donned their tarnished armor and partially concealed the rust by pulling on brilliantly colored surcoats. Henry, wearing the colors of both England and France, heard three separate masses and took communion, Then directed his commanders to form their men for battle. The knights were placed shoulder-to-shoulder, four deep, with wedge-shaped clusters of archers placed among them, wearing sturdy iron helmets and short-sleeved chain-mail tunics beneath studded leather vests.

Once formed, Henry’s front line was 1,200 yards wide, arrayed in a field bordered by thickly tangled woods. Two roads ran through the woods, one to the village of Agincourt on the left and the other to the smaller village of Tramecourt on the right. Although inwardly anxious, Henry put on a brave face, counting heavily on the legendary skill of his archers to balance the odds. He knew from experience that his longbowmen could shoot a remarkable 12 arrows per minute, with an armor-piercing range of up to 60 yards. At least they could do so when they were in top form—many were now in less than peak condition. Although the English archers had last eaten decent bread four days ago, all remained remarkably purposeful as they strung their six-foot-long bows and drove crudely sharpened stakes into the wet ground to protect their position against cavalry charges. They knew, or had been told, that horses would slow instinctively as they came upon such stakes and either come to a complete halt or else wheel off to the right or left.

Opposite the English, the French waited in the dull morning light for renewed truce negotiations to conclude. Although admittedly in a tight spot, Henry rejected the haughty terms offered him by the French, who waited for him to make the first move as they watched the ragtag English force across the recently ploughed fields. The French were arrayed in three great lines, called “battles,” with knights in each packed 40 men deep. On each flank were the mounted men-at-arms, including 12 princes of royal blood, while the center contained dismounted men-at-arms. Altogether, roughly 24,000 Frenchmen were poised to destroy 5,800 Englishmen.

The ground between the armies was thoroughly soaked from the recent rains, and to many of the experienced English yeomen it looked treacherous at best. In contrast, the French knights in the first line appeared completely oblivious to the likelihood of the field turning into an absolute quagmire. Instead, they jostled each other for favorable positions, pushing aside less exalted soldiers to take their places in the front line. The nobles on the flanks believed that a brave man on a good horse could do more in an hour of fighting than a hundred men could on foot, an exaggerated confidence that had cost previous French armies dearly when facing the less bombastic English. So many personal banners flourished above the ranks that the order was given to furl them and send them to the rear, much to the dismay of the proud seigneurs.

Over on the English side, the right flank was arrayed under the command of the decidedly overweight, 42-year-old Duke of York. Lumbering about in his armor, York was backed up by the Earl of Oxford. Henry stood in the center, while Lord Camoys (with over 40 years of experience against the French) commanded the left flank. With insufficient troops for a reserve, Henry could detail only 10 men-at-arms and 30 archers to guard the English baggage train. Contrary to the French lineup, which was a mix of mounted and unmounted knights, all of Henry’s knights were dismounted. They shifted from foot to foot in the cool morning air in a generally fruitless attempt to keep warm, while Henry’s archers chose to sit behind their poles and drink whatever beer they might still have with them.

The lack of movement, which endured until just before midday to allow for a new round of negotiations, had been a source of growing discomfort and anxiety among the English. Many of the men, still suffering from dysentery, had to relieve themselves where they stood. Knights strapped into their heavy plate armor could not even do that. Henry knew that he must do something soon to provoke a French attack; otherwise, he and his men would simply weaken and starve. Rising to his full height, the king shouted to the men: “Banners advance in the name of Jesus, Mary, and St. George!” At that, a great shout went up along the English line.

At the king’s command, Henry’s archers rose up and prepared to advance, remembering what he had told them earlier that morning to increase their fervor: that the French would ruin forever any captured bowmen by cutting off the middle three fingers of their right hands. Sir Thomas Erpingham, 58-year old Knight of the Garter, a holdover from the late Henry IV’s inner circle, rode to the front of the archers, where he ordered them to move a half-mile forward to bowshot range. Advancing this distance, they replanted their poles in the soft ground, presenting an odd picture in that many were naked below the waist (so that they could deal more easily with their continuing dysentery).

The Key Factor: Mud

Once the English archers were in place, the comparatively thin line of English knights kneeled awkwardly in their armor to make the sign of the cross before advancing on foot over the waterlogged field behind the archers to a point within 300 yards of the French. The sight of the smaller English army boldly advancing so excited the mounted French knights on each flank that they largely abandoned discipline to break into a ragged attack, shouting, “Montjoie! Saint Denis!” As they spurred their horses onward, the soggy ground beneath them was churned into clinging mud, which slowed the charge immediately. Nonetheless, cheers rose from the other French nobles standing behind them as they caught the excitement and moved forward as well.

As might have been anticipated, horses quickly began to slip in the mud. As this happened, the French attackers converging from both flanks were thrown into confusion by devastating volleys from the English archers, dispatched in four clouds of arrows. Although the French knights’ armor deflected many of the arrows, their less-well-clad horses were not so fortunate—they stumbled or dropped in their tracks. Some knights were pitched to the ground. Riderless mounts bolted about, colliding with advancing French foot soldiers. By now, horses and men on the field were ankle-deep in mud. The French artillery, intimidated by the first flight of arrows, had pulled back rather than face more steel-tipped projectiles.

Less than a hundred of the mounted French knights ever reached the spike-barricade placed by the English archers. The rest lay mired in the churned-up mud—dead, wounded, or stumbling about in a daze. French cavalry commander Guillaume de Saveuse was one of the dead, killed by a mallet blow or stab wound through his armor-joint after his horse impaled itself on one of the spikes. Without pause, the second line of French began to advance on foot, moving ponderously through the mud in face of flights of arrows. Although it continued to be a cool day, the knights began to sweat in their 60 pounds of armor from the exertion of trudging through the mud. As they proceeded, many could not avoid stiff-legging their way over the dead and wounded, causing any number to suffocate in the mud.

The footing grew worse as the centers of both armies locked together in hand-to-hand combat. Slowly the reinforced French attack drove the English center back, and the battle lost its form in the confined area between the woods. By one account, Henry “fought not as a king but as a knight, leading the way when possible, giving and receiving cruel blows.” The English middle rallied as the right flank engaged, but the obese York was trampled under foot. He either suffocated or suffered a heart attack, since his armor-clad body was found afterward without a wound. The Earl of Oxford was killed also, but Henry called upon Robert Howard, one of the ship captains and a friend of his youth, to take the earl’s place. Howard rose to the occasion as the English archers dropped their longbows to wade into the fray, wielding their axes and short swords.

By now, the French knights were so crammed together they could barely swing their own weapons, and when they were knocked down they found it impossible to get up from the mud in their heavy armor. The more nimble English archers made many French knights lame by slashing their short axes against the backs of their adversaries’ knees. Those sprawling on the ground were helpless to protect themselves from the archers, who mercilessly thrust their daggers through the slits of visors or into the mail covering armpits or groins. The Duke of Alenon, finding himself cut off and surrounded, shouted his surrender to King Henry, who was a few yards away coming to his brother Gloucester’s aid. Before the king could intercede, however, Alenon was slashed and beaten to death by swarming English archers. The Duke of Brabant, younger brother of the Duke of Burgundy, borrowed a lesser nobleman’s armor and galloped into the fray only to be unhorsed and quickly dispatched by archers who did not recognize his worth because his borrowed armor did not mark him as a man of distinction.

In the first two hours of the three-hour battle, the French suffered a staggering 5,000 killed in a bloodbath that included three dukes, five counts, and 90 barons. By this stage, more English knights and archers were gathering up prisoners than continuing to fight. (A French noble would fetch enough in ransom to make a poor man comparatively comfortable for life.) Meanwhile, the knights in the third French line watched the disastrous scene. In a cruel mix-up, Henry ordered the French prisoners killed when he heard that a newly arrived enemy force (actually bands of local peasants) was attacking his lightly guarded rear. The order was only fitfully obeyed by the English nobles, who found it morally repugnant to kill their French counterparts after they had surrendered, and Henry had to deputize a force of 200 low-born archers to carry out the brutal and unnecessary slaughter. When it became evident that the uncommitted third French line, daunted by the fate of the first two lines, was withdrawing from the battlefield, Henry rescinded his order, but by then dozens of duly surrendered French nobles had met a most ignoble fate in the bloodstained mud at Agincourt.

Henry Thanks God for the Victory

For his part, Henry lost fewer than 1,000 men. Only one peer besides the Duke of York was killed that day—the young Earl of Suffolk, whose father had perished at Harfleur. After praising God for the victory in his battered helmet and muddied armor, Henry honored a handful of his equally mud-splattered men for their bravery in a battlefield ceremony. All but one of them (who died shortly of his wounds) was raised to the rank of Knight Banneret, equivalent to a baronet, including Robert Howard. Although the rank was not hereditary, it meant that those honored could from then on carry a four-foot-square banner bearing their own coat of arms.

Henry then summoned the heralds of the two armies, who in approved style had watched the battle together, to formally ratify his victory and suggest a name for it. They suggested Agincourt, after the nearest fortified place, and Henry accepted the name before departing with his army and over 1,000 prisoners to Maisoncelles, his camp the night before, where 20 surgeons set to work on the wounded. The next morning it was again raining, and Henry roused his army one more time to make the final march to the safety of Calais. There was still considerable anxiety that another French force might attempt to block the way, and the worry helped sustain everyone’s endurance during the subsequent march to the coast.

Henry’s heroic army finally reached Calais on October 29, 23 days after leaving Harfleur for what was expected to be an eight-day march. In Calais, the men enjoyed their first substantial food in weeks, while Henry and his officers organized an auction of the ordinary French prisoners; the more noble prisoners were segregated from this auction and would be taken back to England, where they would be held for huge ransoms. One, the Duke of Orleans, was kept in genteel confinement for 25 years before his ransom was secured. In these accepted ways, the victors of Agincourt enriched themselves splendidly. One in particular, Robert Howard, gained enough wealth to attract the daughter of the Mowbray Duke of Norfolk and, years later, to bring the dukedom itself to the Howards.

Henry and his army sailed for England on Saturday, November 16, in a raging storm. Although two ships sank, the others reached Dover in a fast crossing as night was falling. Seven days later Henry entered London, where he was greeted as a hero. Displaying an uncharacteristic modesty, the king accepted no credit for the victory, saying that it belonged to God alone. Given the long odds and tremendous difficulties he had faced during the campaign, Henry might be excused for attributing his triumph to divine intervention. Any way one looked at it, the English victory at Agincourt had been a sort of miracle, and the “happy few” who had stood alongside him on Saint Crispin’s day were, indeed, a “band of brothers.”

Wonderfully written and made me feel as if I was there

A minor edit is needed

“who would be were held”