By Sam McGowan

On March 2, 1933, only a few weeks after the inauguration of Franklin D. Roosevelt as President of the United States, the most spectacular event in the entertainment world premiered in New York. It was a high-tech production that utilized models and new photographic methods to tell the story of a giant ape from a South Pacific island that went on a rampage after escaping its captors in New York and was shot off of the Empire State Building by U.S. Army aircraft.

Few members of the audience realized that the actor playing the pilot was not only the creator and producer of the film; he was also a former Army bomber pilot who had fought in two wars and been a prisoner in both. Of course, no one had an inkling that within a decade the pilot would be a principal player in an ambitious plan to bomb Tokyo, or that he would become an instrumental figure in the two most desperate theaters of World War II, serving as chief of staff for Generals Claire Chennault and Ennis Whitehead and on the staff of Far East Air Forces Commander General George Kenney.

Although he would become most famous as a Hollywood producer, Merian Caldwell Cooper was a man born to adventure—and to war.

Merian was afforded the best education. After completing his preparatory education at Lawrenceville School in New Jersey, Cooper was appointed to the United States Naval Academy by Senator Duncan Fletcher, a family friend. Although he made it through three years of discipline and intense study, he got into trouble during his senior year and washed out.

After living homeless for a while, Cooper’s first employment was as a reporter for a Minneapolis newspaper. He moved from there to Des Moines, then St. Louis, each time accepting positions with local newspapers. In 1916, he joined the Georgia National Guard. His unit was called up and sent to Texas and New Mexico in pursuit of the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa.

Cooper’s desire to fly had never waned, and he enrolled in the Georgia School of Military Aeronautics in Atlanta. He excelled, graduating first in his class of 150. Cooper was eager for combat, but more training awaited him in France at the flying school at Issoudun after going overseas as adjutant with the 201st Aviation Squadron.

Cooper volunteered for the bomber school at Clermont-Ferrand. Upon completion of his training, he asked for immediate transfer to a combat unit, and his wish was granted. He went to the 20th Aero Squadron as a pilot.

Shortly after he joined the squadron, it became part of the 1st Day Bombardment Group, the premier bombardment unit of the United States Army, when it was formed with the 11th and 96th squadrons in addition to Cooper’s 20th.

Like his fellow pilots and observers, Cooper realized that his days were numbered as long as he was flying the DeHavilland DH-4 Liberty bomber, but they all went out each day. And each day a few failed to come back.

On the morning of September 26, 1918, he was shot down and captured along with his observer/gunner. Both men were wounded and became prisoners of the Germans.

The men recovered, and Cooper learned after the Armistice that had been promoted to captain several weeks before he was shot down. He would later learn that he had been recommended for the Distinguished Service Cross, an honor he would decline on the basis that he didn’t deserve it any more than anyone else in that formation that day. Cooper would later memorialize the day in the movie The Lost Squadron.

Cooper became convinced that communism was an enemy of liberty, and this belief became the focal point of his life. Still in the Army, Cooper volunteered to go to Poland with a humanitarian mission being organized by Herbert Hoover. While his military status forbade combat, he visited the front lines as often as he could. He remained with the food mission until June 1919, when his request for a transfer was approved.

While in Poland, Cooper had been lobbying the Polish head of state for permission to become a pilot. He recruited fellow veterans, and in January 1920 the Kosciuszko Squadron entered combat against the Red Army.

Cooper flew more than seventy combat missions against the Soviets, mostly in Austrian Albatross D-3 airplanes. Cooper and his friend Buck Crawford were shot down in June, but they managed to fight off the Russians and escape. On July 13 Cooper was hit again, but this time his luck failed to hold.

Cooper was famous as the number-two man in the American squadron, but he Russians never learned his true identity during the 10 months he was captive. On April 12, 1921, Cooper and two Polish officers managed to escape.

When he returned to the U.S., Cooper settled in New York City. He worked for the New York Times, but his love of adventure had been stimulated by his years in Europe.

Cooper’s association with films led him to Hollywood, where his King Kong production established him in the motion picture industry. Cooper saw his role in films as an opportunity to promote patriotism as war clouds gathered in Europe.

Although it had been two decades since he had worn the uniform, Cooper still held a commission in the Army Reserve. Several of his friends returned to service, and on June 16, 1941, Cooper also returned as a lieutenant colonel, joining such others as the famous air racer, James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle. Cooper was appointed executive officer for A-2 (Intelligence) on the staff of the United States Army Air Forces directly under General Carl Spaatz, the commander of Army Air Combat Command.

In early 1942, the War Department began making plans for a bombing campaign against the Japanese homeland from airfields in China, most of which at the time was still free of occupation. Cooper was assigned to a special project—codenamed AQUILA—under the command of Colonel Caleb V. Haynes that was to deploy to India, then to China to form the nucleus of X Bomber Command.

Prior to his assignment to Haynes’ project, Cooper had made the acquaintance of a young Army colonel at a Hollywood party. Although Colonel Robert L. Scott was a pursuit pilot, Cooper had been impressed by him and persuaded Haynes to request that he be assigned to the AQUILA force.

Prior to their departure for India, Cooper met with General Henry H. Arnold, who informed him that the B-25 medium bombers destined for China would be deployed by aircraft carrier, and that if they got underway before Haynes’ unit arrived in India, they would attack Japan while enroute. Shortly after their arrival in New Delhi, Cooper got word that the B-25s were at sea.

As the Tenth Air Force intelligence officer, Cooper went to China to debrief Doolittle after his historic raid on Tokyo. Claire Chennault was still in China advising the Chinese military as a civilian, although plans had been made to bring him back into the Army along with his recently established American Volunteer Group.

The Doolittle Mission, as it is popularly known, was a psychological—and political—success, but its fallout led to a scrapping of plans to use China as a base against Japan. The loss of the Chinese bases coupled with a new urgency in Africa led to major changes. Haynes, Scott, and Cooper were told to organize a “ferry” of supplies to China, but a Japanese offensive in Burma led to more urgent matters. The Assam-Burma-China Ferrying Command was put to work hauling ammunition and other supplies into Burma; then, as the situation worsened, they turned to evacuating British troops. Scott reported in his memoir God is My Copilot that on one mission with Cooper aboard as a volunteer radioman, they fought off Japanese fighters with submachine guns.

The shakeup in the CBI produced major political problems that would involve Cooper personally, resulting in his eventual transfer out of the theater. General Clayton Bissell was elevated to command of Tenth Air Force under the direct command of General Joseph Stilwell, who arrived in China in February 1942 as head of the military mission and Allied chief of staff to Chiang Kai-shek.

Cooper had gone to the CBI under two sets of orders, one assigning him to Hayne’s command and a second that more or less gave him carte blanche to go wherever he wanted in his capacity as an intelligence officer. Cooper decided to use his special orders to throw in his lot with Chennault, and as the Japanese ran the Allies out of Burma, he went to Chunking to join him. Chennault made the maverick colonel his new chief of staff.

War Department plans called for the induction of the American Volunteer Group into the Army to form a new fighter group. Scott was selected to command the new 23rd Fighter Group while Haynes returned to his previous role as commander of the Bomber Command in the new China Air Task Force, an advanced element under Tenth Air Force commanded by Chennault, who was supposed to report to Bissell. Army Chief of Staff General George Marshall was fearful of Chennault’s power and brought him into the Army as a brigadier general one day after Bissell attained the same rank, making him the senior officer. The move infuriated Chennault, who detested Bissell from past assignments at the Fighter School at Langley. It was a purely political move, designed to ensure that Chennault was subordinate to both Bissell and Stilwell, and a decision that seriously affected the Allied effort in the CBI.

Chennault and Cooper were an ideal match. Both were Southerners, and both had the same disregard for the authority of senior officers whose careers had been based more on politics than operational experience. Neither Stillwell nor his superior, Marshall, had ever commanded troops in combat. Neither, for that matter, had Chennault while serving in the U.S. Army, but he had been in China for four years and was thoroughly familiar with Japanese tactics and military capabilities. Bissell had attained ace status in World War I but had never comprehended the new tactics offered by improved aircraft performance. Bissell was particularly ignorant of the tactics of interception of bomber formations.

Cooper fell into disfavor with Bissell when he threw his lot in with Chennault while the AVG was still active. Previously, the two men had gotten along well, but Bissell considered Cooper’s act as traitorous and began seeking a way to get him out of China. Cooper worked closely with Chennault planning missions against Japanese targets that were later termed as “aerial guerrilla warfare.”

Yet, even while Cooper worked to defeat the Japanese, Bissell finally got him out of China when he got word that Cooper had been seriously affected by dysentery. Bissell order Cooper back to India.

Cooper finally left Chunking in late November for New Delhi, where Bissell dismissed him from further service in China. In spite of his insubordination, Chennault had been retained, but he was being punished by the loss of Cooper. When he returned to the U.S., Cooper added to his problems when he met with General Marshall and told the senior officer of the Army that his man in China—Stilwell—had Communist sympathies.

Marshall, who some believed was also pro-Communist, was incensed and told Cooper that if he didn’t retract the statement, he would never see another promotion or decoration as long as he was in command of the Army. As a civilian in uniform for the duration, Cooper was not intimidated by Marshall and refused to make the retraction.

But Cooper already had an ally. In 1917 he had become friends with a young officer by the name of George C. Kenney, who in 1942 had gone to Australia to become the chief of staff for air under General Douglas MacArthur. Kenney got word through some of his officers who had been in the States that Cooper had been sent home from China. Knowing that Cooper was an energetic worker, he immediately put in a request to have him reassigned to his command. Cooper left for Australia in May and reported to Fifth Air Force commander Kenney, who assigned him to New Guinea as General Ennis Whitehead’s chief of staff.

Cooper arrived in New Guinea at an opportune time. Fifth Air Force was gaining air superiority over the Japanese, and Kenney had produced a plan to establish an air base deep in the interior to bring his fighters, attack bombers and transports into closer proximity to the Markham Valley, which he intended to seize in an airborne assault. As Whitehead’s chief of staff, Cooper was responsible for the planning, which called for the construction of a base near Marlinan, a facility that would be supported entirely by air. A second airfield was established in another location to serve primarily as a diversion to keep the Japanese from discovering the new base at Marlinan and to serve as an emergency landing strip.

Once the airfield had been established, Fifth Air Force brought up fighters and medium bombers in preparation for the attack on the airfield at Nadzab, which Kenney intended to use as a landing zone for transports bringing in troops to attack the Japanese garrison at Lae from their rear. The attack on Nadzab went off like clockwork while Kenney and his boss, General Douglas MacArthur, watched “the show” unfold from a B-17 bomber circling above.

As Fifth Air Force chief of staff, Cooper was once again serving with a shoestring force in a remote theater, but this time he was under a theater commander who had full confidence in the airmen beneath him. He knew MacArthur personally. He was also part of a command famous for innovation.

Cooper remained as Whitehead’s chief of staff for 18 months and proved invaluable in the planning of the operations that allowed the Far East Air Forces to spearhead an offensive northward from Papua, New Guinea, toward MacArthur’s beloved Philippines. Kenney was constantly fearful for Cooper’s health. Not only was he plagued by dysentery and fatigue, but he was also rumored to have suffered a heart attack before the war. In October 1944, just before the Leyte landing, Kenney told Cooper to go home for a month of recuperation leave and then fly to London to assist with the transfer of Eighth or Ninth Air Force from Europe to the Pacific theater.

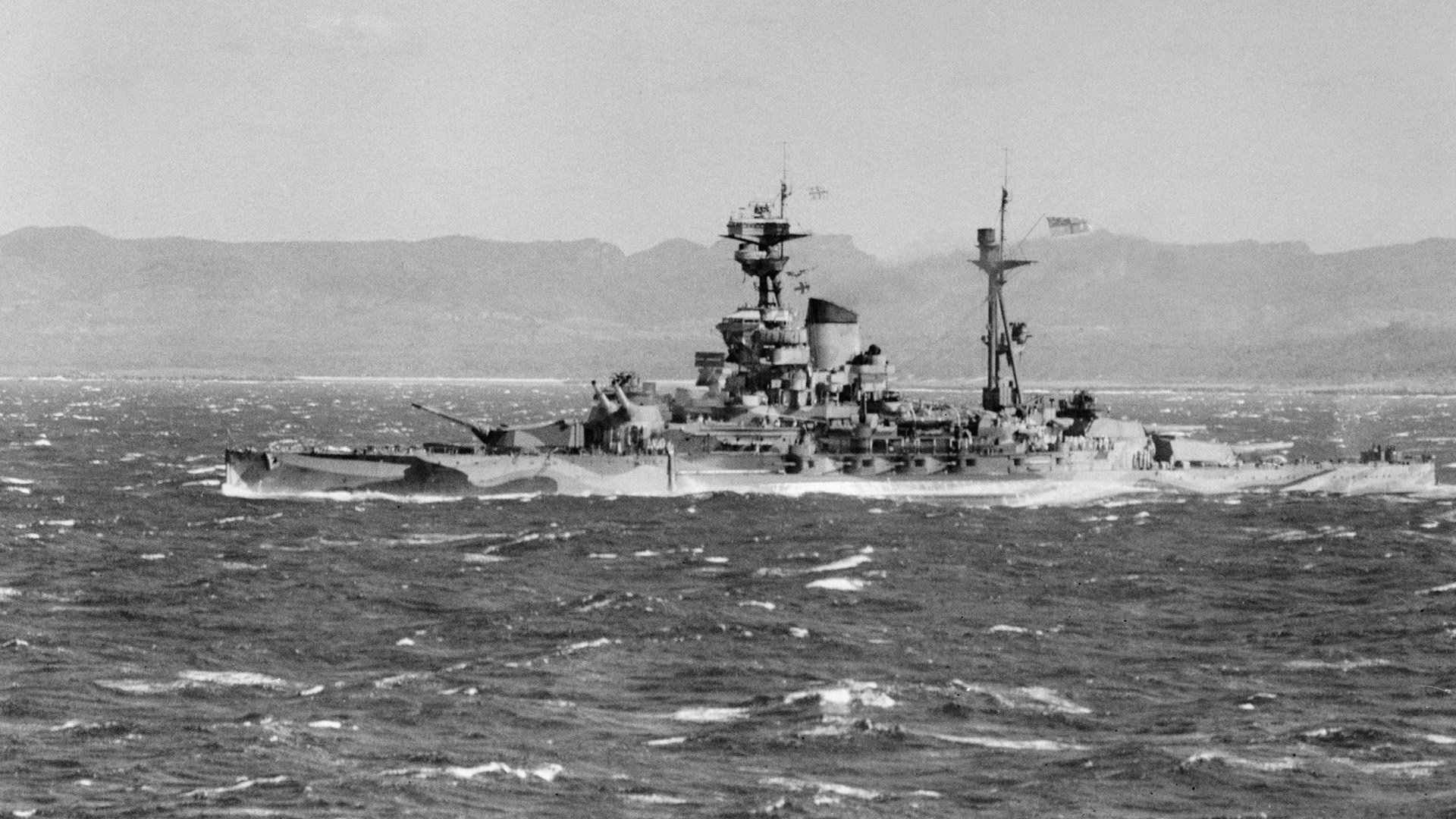

It would be 10 months before Cooper would return from Europe. On June 25, 1945, Kenney received a wire from him that he was back in the United States after completing his assignment and was looking for work. Kenney wired back for him to report to Manila as soon as possible. By this time, the war had moved north to Okinawa, where Whitehead had established Fifth Air Force headquarters. Kenney made Cooper his deputy chief of staff. Cooper remained with Kenney through the end of the war and stood with him aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay during the Japanese surrender.

Had it not been for his run-in with Marshall after his return from China, Merian Cooper would have probably been promoted to high command. His name was sent up for promotion to brigadier general numerous times, but each time it was stricken from the list before it went to the U.S. Senate for confirmation. Marshall retired from government in 1950, and as soon as he was gone, Cooper joined other blacklisted officers—including Charles Lindbergh—on the promotion list to brigadier general in the Air Force Reserve.

Although he had spent most of his life as a civilian, Cooper proved indispensable in the two most dramatic areas of operations of World War II. Claire Chennault was especially bitter over having Cooper taken away from him and had continually beseeched Arnold to return him. Had Arnold been so inclined, Kenney would doubtlessly have protested the transfer. After the war, Cooper returned to Hollywood and the motion-picture business, where he produced a number of movies aimed at promoting the officer corps, most with John Wayne in a starring role.

One of the projects he most wanted to complete was a movie about the life of Claire Chennault, but it never came to be. Cooper died on April 21, 1973, at the age of 79.

Author Sam McGowan is a pilot and veteran of the U.S. Air Force. He resides in Missouri City, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments