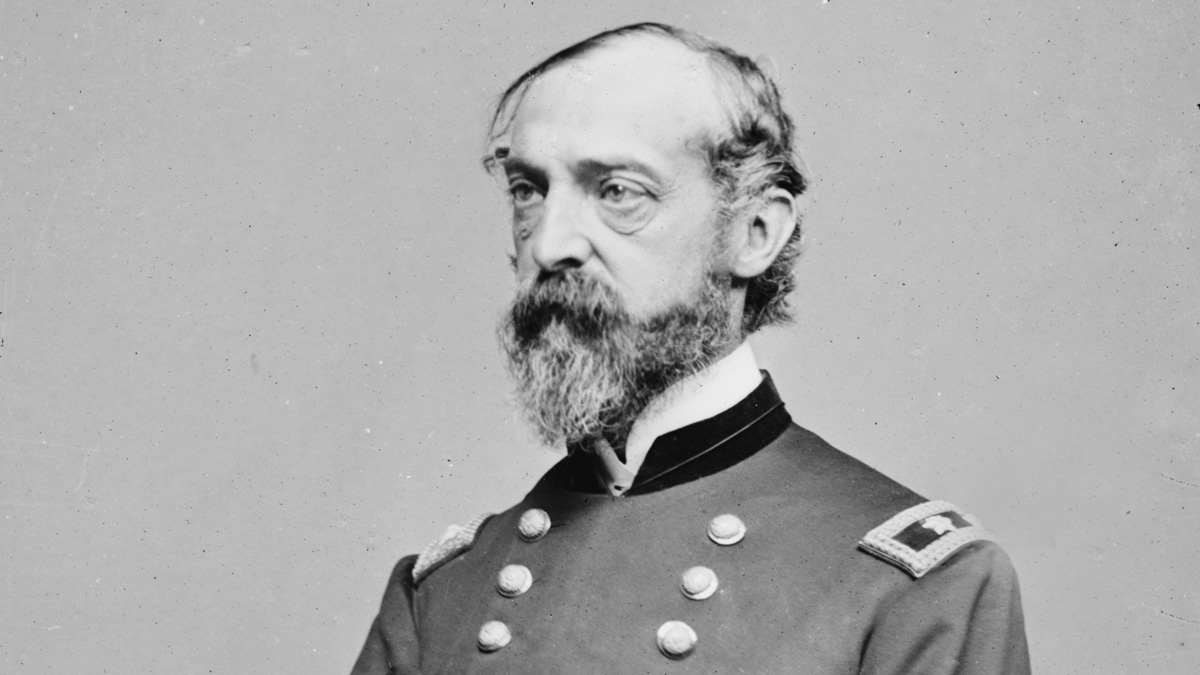

George Gordon Meade did not want command of the Army of the Potomac when it was thrust upon him on the eve of the Battle of Gettysburg seven months after the Union defeat at Fredericksburg, but he had the distinction of being the division commander who had led the successful Union assault during the bloody battle in December 1862 on the south side of the Rappahannock River.

Unlike major generals George McClellan and Joseph Hooker, Meade was not a glory seeker. Meade was satisfied when Hooker appointed him to command the V Corps during the Chancellorsville Campaign. He marched his V Corps into Pennsylvania in summer 1863 without dreaming he would be the one squaring off against General Robert E. Lee at the crossroads town of Gettysburg.

Just before sunrise on June 28, 1863, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton’s chief of staff James Hardie awoke 47-year-old Meade at the V Corps encampment at Prospect Hall in Frederick, Md., to present him with command of the Army of the Potomac. Meade declined the promotion, but Hardie informed him that Lincoln was not asking him to take it, but ordering him to do so.

In the days preceding this event, Meade had written a letter to his wife informing her that he was quite unlikely to be offered the army command. “I do not … stand any chance, because I have no friends, political or others, who press my claims or pretensions,” he wrote.

As for the officers in the army, many of them had expected President Abraham Lincoln would appoint McClellan for a third time to lead the Army of the Potomac at such a crucial time. But they were dead wrong.

When the Philadelphia family in which he was growing up fell on hard times, Meade secured a free college education at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. When war erupted in 1861, he received command of a brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves in time to lead it during the Seven Days Battle in early 1862.

Promoted to division command for the Antietam campaign, he showed great promise in the hard fighting at South Mountain and during the I Corps attack against the Confederate left wing at Antietam. While watching Meade’s attack against the Confederate left at Turner’s Gap, Hooker expressed his admiration. “Look at Meade! Why, with troops like those, led in that way, I can whip anything.”

Lincoln needed a cool-headed, fearless, and honest commander. Meade embodied those attributes. But no commander was perfect. Meade’s gruff, irascible nature was often on full display while campaigning.

Lincoln planned to replace Hooker after he was defeated at Chancellorsville. Officials from Washington interviewed a number of corps commanders in the Army of the Potomac to see if they were interested in commanding the army. Maj. Gen. John Reynolds (I Corps), Maj. Gen. Darius Couch (II Corps), and Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick (VI Corps), each of whom had seniority over Meade, all recommended him. “Meade is the proper one to command this army,” Sedgwick said.

After reviewing the information presented to him by his advisors, Lincoln decided on Meade. Lincoln concluded that Meade would fight well to protect the soil of his home state. “[I believe] he will fight well on his own dunghill,” Lincoln said.

In the dangerous situations that unfolded on the second and third days of the bloody clash at Gettysburg, Meade was in the thick of the action. He made sure that reinforcements arrived where they should in time to prevent the kinds of disasters suffered by his predecessors at First and Second Manassas, Richmond, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. To Lincoln’s credit, he had finally found a competent general.

—William E. Welsh