By Phil Zimmer

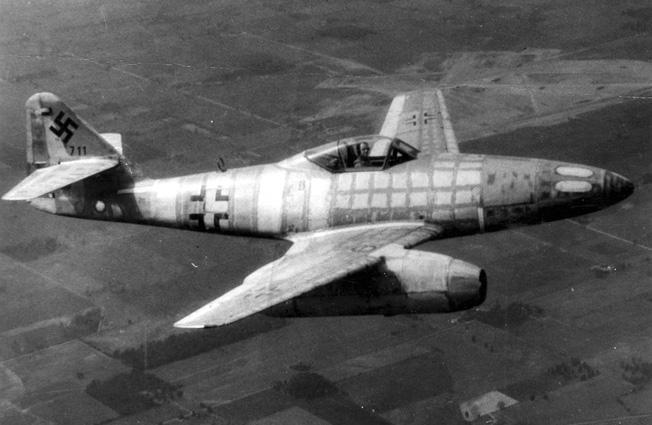

The Germans knew the bombers were coming, and they prepared even as the U.S. 457th Bomber Group first assembled in the early morning sunlight over faraway London. That March 18, 1945, raid on Berlin included more than 1,220 Allied bombers and scores of North American P-51 Mustang fighters contending with heavy German flak and tangling with fast-flying German Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighters employing air-to-air rockets operationally for the first time.

A Twelve-Thousand-Foot Jump

It was the last great air battle of the European war, one that would be a final, deadly encounter for many American flyers and nearly so for Oberleutnant Gunther Wegmann, commander of Jagdgeschwader 7’s 9th Squadron of Me 262 jets. Wegmann led his squadron in a loose formation toward the incoming bombers. He and his two wingmen fired their R4M rockets into one tight formation of some 60 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress bombers from a distance of 3,000 feet. The scores of rockets created devastation, with bits of aircraft, smoke, and flame erupting from the formation of bombers.

The squadron then scattered for the homeward flight. That was when Wegmann spotted another formation of enemy bombers and swung around to take a pass at them with his MK 108 “machine cannons.” He swooped in from astern and came within 600 yards of one bomber before opening up with a staccato of fire that ripped away the cowling from one of the target’s engines.

Wegmann was jubilant and started to transmit his victory to home base when a stream of enemy fire struck his jet, splattering his canopy, tossing instruments from their panels, and studding his plane with bullet holes. Worse yet, his right leg was numb. Reaching down, he discovered a large hole just below his knee. But he felt no pain at that point as his plane streaked along at 18,000 feet above war-torn Germany.

He desperately pushed his shot-up jet downward, and at 12,000 feet he saw flames leaping from his starboard engine. That quickly ruled out a crash landing that would turn his plane into a giant fireball. He decided to push the control stick forward, disconnected his seat straps, removed the retaining bolt from the plane’s canopy, and was sucked from the cockpit at 250 miles per hour. Wegmann bounced off the plane’s tail and fell free. He counted five long seconds before pulling the release cord of his parachute and drifted downward toward the town of Wittenberge 60 miles northwest of Berlin. He brushed the tops of pine trees and managed, just barely, to land in a small meadow.

“German pilot!” he shouted loudly as an elderly woman made her way to him. Wegmann’s luck held. The woman was a nurse who quickly bound his thigh above his right knee and applied a tourniquet. Within four hours he had been rushed to a hospital where his leg was amputated.

Others were not so fortunate that day, including five American fighter pilots who failed to return home. Sixteen Allied bombers were hit by flak and either crashed on their approaches to Berlin or managed to make emergency landings behind the advancing Soviet lines east of the German capital. Another 25 Allied bombers were destroyed with the loss of only two German jets. The pilots acquitted themselves well that day against overwhelming odds, yet the effort of the German jet fighters was to prove too little too late in the face of relentless Allied assault from the air, land, and sea with their overwhelming war matériel and seemingly endless supply of manpower.

“It was Like Being a God”

The Me 262 did have a significant influence on the later stages of the war. It was the world’s first operational turbojet fighter, and it simply outclassed any plane flying at the time. It reportedly could reach speeds of 540 miles per hour with a cruising speed of 460 miles per hour and a range of some 650 miles. The Me 262 had a ceiling of 38,000 feet, and it could climb at 3,940 feet per minute with its two Junkers Jumo engines, which produced 1,980 pounds of thrust apiece. In its standard configuration, the single-seat jet was armed with four 30mm MK-108 cannons and the plane could be modified to carry 1,000 pounds of bombs.

It was the development of the feared R4M rockets that sealed the fate of many Allied flyers over Germany when facing the Me 262. “The rockets gave us extra punch,” said Me 262 pilot Leutnant Klaus Neumann. “Fire the rockets, do the damage, weaken the tight formation integrity of the bombers, and then pick off the crippled stragglers,” he said.

“It was like being a god in a way,” added Neumann, who had seen combat in piston-driven Messerschmitt Me-109s and Focke Wulf FW-190s over Russia. The jet was “fast, had great firepower,” and gave one a lot of confidence when pitted against a well-armed enemy aircraft, he said. The 55mm R4M rockets contained a high explosive shell filled with Hexogen and were mounted under the wings on specially designed wooden racks with 24 rockets typically attached to each jet.

Initially, there were problems because the rockets often failed to fire. Reports of the problem reached Generalleutnant Adolf Galland, head of the Luftwaffe’s jet arm. An electrician was promptly called in. The electrician quickly identified a problem with the copper electrical triggering connectors. From that point forward, the connectors were reinforced with silver or nickel, and the difficulty was resolved.

Each of the Me 262’s four MK-108 30mm cannons could pump out more than 650 rounds per minute. The specially produced MK cannon was considered a masterpiece of weapons engineering because of its stopping power, compact size, and ease of manufacture. German engineers noted that it could knock down enemy bombers with a minimum expenditure of ammunition while staying beyond the range of enemy counterfire.

The newly developed Jumo 004 engines presented challenges, occasionally pulling in debris after an enemy plane had burst apart, damaging the compressor, and causing a flame out. Flying on one engine, the Me 262 could not easily take evasive action or even outrun an Allied P-51 Mustang, Republic P-47 Thunderbolt, or the De Havilland DH.98 Mosquito. In that situation, the Me 262 pilot had to reach a friendly base as quickly as possible. Galland was particularly disgruntled with the jet power plants. Germany’s war economy lacked many of the needed specialty metals for the jet engines that, on average, lasted less than 12.5 hours before needing to be changed out. That problem became far worse toward the end of the war as nickel and chromium supplies petered out. Many of the newly unpacked engines at that point did not even make it through the onboard testing process before failing and needing to be replaced.

The Nazi engineers knew that the engine’s compressor had to be brought up to speed before the ignition of the turbojet. They resorted to a small two-stroke gasoline engine located behind the engine nozzle, while many postwar jets came to rely on a high-torque electric motor or airflow from a small starter turbine engine.

The Me 262’s starter engine relied on an electric start, with a pull-cord starter with a handle serving as backup. One can only image the frustration of a Luftwaffe mechanic needing, on occasion, to tug on a lawnmower-type pull cord to get the state-of-the-art jet engine fired up. The jet came with armored front glass and an armored seat back but lacked an ejection seat. The pilot was to pop the canopy, gently roll the plane over, and slide out or remain horizontal and let the plane’s speed suck him out as Wegmann elected to do late in the war.

First Flight of the Jet Fighter

The Me 262 first took flight on March 25, 1942, when test pilot Fritz Wendel achieved a test flight speed of 541 miles per hour, almost 100 miles per hour above the speed of the Mosquito or anything the Americans could field. The smooth, shark-shaped plane was surrounded by controversy almost from the start, with Hitler insisting that it be used as a fast bomber. Designer Willi Messerschmitt, Galland, and others gave some lip service to Hitler’s request, largely moving forward with their initial plans for a fighter while planning to have the Arado 232 fill the role of a future jet bomber. Hitler’s constant meddling, though, pulled precious time and resources from fighter development to produce a modified Me 262 bomber. Some 232s were also developed as reconnaissance planes and others as night fighters.

Galland remained critical of using the 262 as a bomber, a role it was not designed to play. He remained firmly convinced that the fighter jet could have been put into combat “at least a year and a half earlier” without Hitler’s interference, “and built in large enough numbers so that it could have changed the air war.”

That time estimate is perhaps exaggerated, and Galland did not say it could have changed the outcome, but rather more likely the course of the war, perhaps causing the Allies to reconsider daytime bombing over Germany.

The two-seat night fighter variants proved surprisingly successful, again despite Hitler’s initial misgivings. With a radar operator in the back, the pilot could zero in on the bombers. Oberleutnant Kurt Welter, who had two years’ experience as a night fighter in FW-190s and Me-109s, proved to be the best of the night fighter aces. Using recent analysis, Welter appears to have made 20 confirmed kills, including a large number of Mosquitos, with his Me 262, making him the highest scoring German jet fighter pilot.

The Me 262 in Combat

The first Me 262 fighters were delivered to Luftwaffe field units in April 1944, with the first encounter recorded on July 26 when one of the German jets fired at a British Mosquito, which disappeared trailing smoke but managed to land safely in Italy. On August 8, a unit scored a confirmed kill over a Mosquito. Interestingly, the Allies had received reports of the Me 262 from both the resistance and via the Office of Strategic Services. “The rumors of a super fast German plane were being taken seriously,” wrote Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle, who had led the daring early war bomber raid on Tokyo and later joined the U.S. Eighth Air Force in Europe. “There were just too many corroborating reports from different sources not to take notice, but many of the pilots almost refused to believe [them],” he wrote.

Doolittle recalls one bomber pilot who was stunned at the quickness and severity of an Me 262 attack. One explosive shell, most likely from a MK-108 cannon, entered through the bomber’s bomb bay, killing one and injuring four other airmen. Fortunately, the plane was returning from its bombing run, otherwise the shell could have struck the bombs on board and the resulting explosion could have destroyed several additional aircraft flying in the tight box formation. The young American pilot was in complete shock, recalled Doolittle. “I knew he was never going to be an effective leader again,” he wrote. The Americans realized something had to be done to prevent a severe morale problem.

Countering the German Jet

Additional reconnaissance flights were immediately ordered, and soon the jet airfields were being bombed. This became an ongoing process; one that forced the use of bases ever-closer to the heart of Germany in the face of Allied advances. Eventually, the Germans even resorted to using parts of the autobahn for landing strips and nearby wooded areas to conceal the parked jets from marauding and opportunistic American P-51 Mustang pilots.

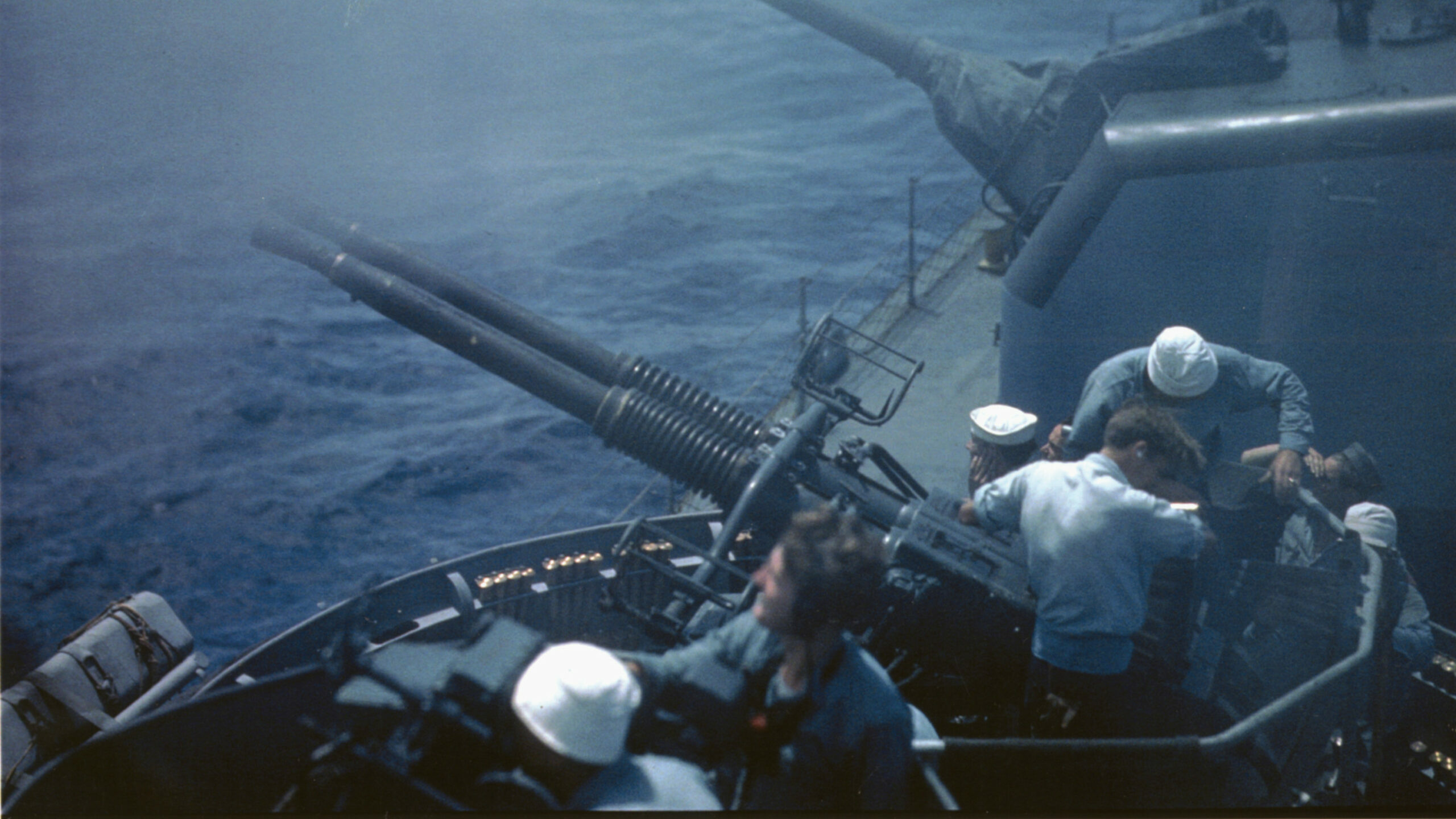

The Allies knew the fast-moving jets were exceptionally vulnerable during landing and takeoff, so the patrolling of the jet airfields paid handsome dividends. The Germans used the airfields as improvised “flak traps,” attempting to lure Allied fighters in where the deadly 88mm and other flak guns—along with covering piston-driven FW-190s and Me-109s—could take a substantial combined toll on unwary Allied pilots who ventured too close.

Galland admitted after the war that the bombing of the factories did not prove overly effective, but the bombing of the petroleum facilities and railways did have a significant effect. “What harmed us the most was the killing of our pilots in combat,” wrote Galland. “Planes can be rebuilt, but men cannot be made.”

The development of drop tanks and the eventual positioning of P-51s on the European mainland gave the fighters more air time over Germany. It was the unleashing of the Mustangs from escort duty with the Allied bombers that made a significant difference. In 1944, the fighter pilots were often given the green light to go in before the bombers and destroy anything that moved, especially the jets rising to meet the slow-moving bombers.

“We had the numbers, we had the best pilots, best aircraft and we were in a sort of blood lust to whack those guys the best and hardest way we could,” said 2nd Lieutenant Francis S. Gabreski, the leading American fighter ace in Europe.

The Allies had a few other tricks up their sleeves, too. One of these was nitrous oxide injection, similar to the Germans’ own GM-1 fuel injection system, which gave them a quick burst of speed to close and fire on the jets. They also found that a tight box formation of four P-51s could reportedly prevent a jet from evading them, especially when the American fighters had the advantage of altitude and position. In that situation, a “jet-propelled plane can be destroyed on every encounter,” according to a report filed in late 1944 by Colonel Irwin Dregne, commander of the 357th Fighter Group.

Operation Bodenplatte: Striking Back at the Allies

While this method of winning through attrition proved effective for the Allies, the Germans had a few surprises, too. Operation Bodenplatte, for example, called for a first strike against all the Allied fighter fields on the continent that the jets and other Luftwaffe planes could reach. Generalmajor Dietrich Pelz believed that if the German planes could destroy half the Allied fighters on the ground and destroy the airfields in the process, then the jets would be able to handle the remainder of the Allied fighters.

Pelz noted the plan was never fully put to the test because of the lack of Nazi planes at that point in the war. The daring operation, however, that took place on January 1, 1945, did result in the destruction of more than 285 Allied planes, including some 145 fighters, with another 180 aircraft damaged and 185 personnel killed, according to recent research.

How Many Me 262s Saw Combat?

More than 1,400 Me 262s were built, but only 50 were approved for combat, according to Galland. Of those 50, there were never more than 25 operational at any given time, he said. It is no secret that continuing engine problems, shortages of fuel, and Allied bombing and strafing of airfields and manufacturing facilities took a toll on the number of available jets.

Some reports indicate that there had been more than 180 Me 262s, including those modified as bombers, but reliable German documentation was problematic at best in the final months of the war. The same thing also holds true for proper documentation on the number of victories achieved by the jet pilots, which may have totaled more than 500 before the war’s end.

The Me 262 was well ahead of its time. If the Nazis had had greater access to refined metals for the jet engines, more fuel reserves, and more time, then things might have played out somewhat differently toward the end of the war. The fact remains that the ground-breaking jet truly set the course for the future of aviation history.

For what it’s worth, the Me262 was not the first turbojet fighter to become operational. The Meteor F.1 was the first operational turbojet fighter, achieving IOC in June 1944. The Me262 achieved IOC in August 1944. Nonetheless, test and development Me262 were involved in combat before June 1944, but they were not operational aircraft.

The Allies were saved from more serious damage to bomber operations by Hitler’s directive to employ the 262 as an attack bomber. Fortunately, much wasted effort was made by German flight engineers to comply with Hitler’s orders. The 262 did not have the bomb carrying capacity nor the range to be used in such fashion. If it had been properly used in early 1944, damage to allied bombing missions would have been severe.

Wonder how many WWII Luftwaffe jet pilots transitioned over to the West German Luftwaffe in the 50’s.