By David H. Lippman

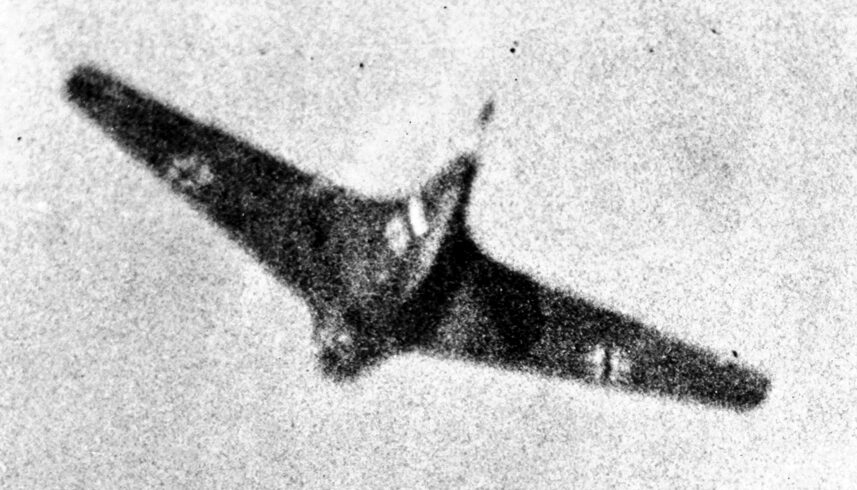

The Germans called it the “Komet” and the “Devil’s Broomstick,” for the incredible speed with which it reached its altitude of 30,000 feet, achieving 0.84 Mach while doing so.

The Americans called it the “Powdered Egg” for its blue color and egg shape.

But postwar historians would rightly regard the German Me-163B rocket fighter as a failed attempt at achieving a revolution in air combat and one of the greatest debacles in military history.

When a new war began to develop in the 1930s, the Germans, Soviets, and even the Americans began to study the exciting possibilities generated by rocket engines as a means to power fighter aircraft at high speeds.

The Germans, who closely studied the works of two titans in the field, Romania’s Hermann Oberth and America’s Robert Goddard, were first off the mark, flying Opel and Espenlaub rocket planes that were little more than gliders with rocket engines attached in the tail. They flew at low altitude over their test areas in the late 1920s but had a tendency to crash.

After that, however, the German Army took over the program, putting it under Captain (later General) Walter Dornberger, whose acolyte, Werner von Braun, was developing the V-1 and V-2 missiles. As part of the Army Weapons Department’s Ballistic Weapons Council, the rocket aircraft program moved to its base at Kummersdorf and went under a secrecy level that was so high that staff members, engineers, and scientists quipped that their reports and memos were “to be burned before reading.”

Three major engineers led Germany’s drive: Alexander Lippisch, an expert on glider design; Hellmuth Walter, who had developed an efficient, small, liquid-powered rocket engine; and the awesome power of Willy Messerschmidt and his company, whose assembly lines were punching out the legendary Bf-109 fighter aircraft and could easily produce rocket-powered planes.

Working under the lowest priority, the three powers designed a rocket-powered interceptor fighter, which could provide point defense for major targets in the Third Reich such as factories, oil refineries, coal mines, shipyards, and cities.

The first major problem was fuel. A chemical combination that was 80 percent hydrogen peroxide, called “T-Stoff,” would be used with a solution of calcium permanganate, methyl alcohol, hydrazine hydrate, and water—called “Z-Stoff”—to power the aircraft. On meeting in the combustion chamber, these fuels would enable the engine to have a thrust of 600 to 800 pounds.

The two fuels were powerful, corrosive, and had a high potential to explode on the ground or in the air. They had to be kept apart as much as possible. Fuel storage was no simple feat. T-Stoff had to be put in aluminum tanks, or it would corrode away or burst into flames. Z-Stoff had to be placed in glass containers for the same reason. Z-Stoff would also corrode aluminum.

The engines were tested in the fuselage of an He-112 fighter and the first two were destroyed in tests. In March 1937, ace test pilot Erich Warsitz climbed into the cockpit between the alcohol and liquid oxygen tanks. To take off, the plane used the usual Junkers Jumo piston engine as a safety measure. Warsitz fastened his straps, ran through his checklist, gave a thumbs-up, warmed up the Junkers engine, followed von Braun’s instructions on how to power up the rocket engine, and the whole aircraft exploded.

Incredibly, Warsitz was flung clear of the wreck and survived with only a few cuts and bruises. Warsitz tried again at the end of April, when a new He-112 with a Daimler-Benz engine was ready. This time the plane took off. At 2,000 feet, Warsitz leveled off, cut the DB engine, ignited the rocket, and felt “like he had been kicked in the backside.” The rocket engine fired for 30 seconds, and he raced through the air at 285 miles per hour for a successful flight.

By June, Warsitz was taking off on rocket power alone. When the plane used up its fuel, he would glide in to perfect landings on a precise cross painted on the runway. Its pilot had to sit in a semi-recumbent position, and Warsitz found the cockpit so cramped that he could not enter and exit if he had his wallet in his pocket.

Meanwhile, Lippisch and his colleagues worked hard on Project X, the delta-wing interceptor plane, basing it on pre-war gliders. These would use the same rocket engines as the He-112 variations.

On June 20, 1939, Warsitz flew an He-176 in a test at Peenemunde that lasted 50 seconds but barely exceeded 170 miles per hour. In attendance were Field Marshal Erhard Milch, second-in-command of the Luftwaffe, and Field Marshal Ernst Udet, the Luftwaffe’s chief of procurement, who owed his position to having been a Great War fighter ace in Hermann Goering’s squadron and thus becoming a lifelong friend of the head of the Luftwaffe.

Udet was the very last person one would seek as a procurement chief. While a brave pilot, charming dinner guest, and talented cartoonist, he was also a hard-drinking womanizer who ignored modern technology and never met an open-cockpit biplane he didn’t like.

Before Warsitz took off, Udet stalked over to the plane and yelled at everyone, “You want to fly with that? It has no wings … those are running boards!”

After the flight, Udet was even harder. “That is no airplane! Leave it alone! I forbid you to fly it again!” he shouted.

With the rocket fighter now in a bureaucratic purgatory, it would take high drama to save it from limbo. Heinkel spoke up for his creation to be flown at a big aircraft display set for the Luftwaffe’s main fighter base outside Berlin at Rechlin, before the whole Luftwaffe top brass and Adolf Hitler himself. Incredibly, Udet agreed, seeing that doing so was an opportunity to showcase something newer than the propeller-driven planes the Fuehrer had seen at Nazi Party rallies for years.

“The Fuehrer must be shown something new, and I suddenly remembered your comical bird! If it can get around the airfield, that will be good enough!” Udet told Heinkel.

On the big day, Warsitz rocketed his He-176 to 2,500 feet, circuited the airfield at full power, and glided to a neat landing. Hitler asked Heinkel, “What does Warsitz get for this flight?” With that, the rocket fighter had the support it needed, and the engineers got to work on what would become the Me-163.

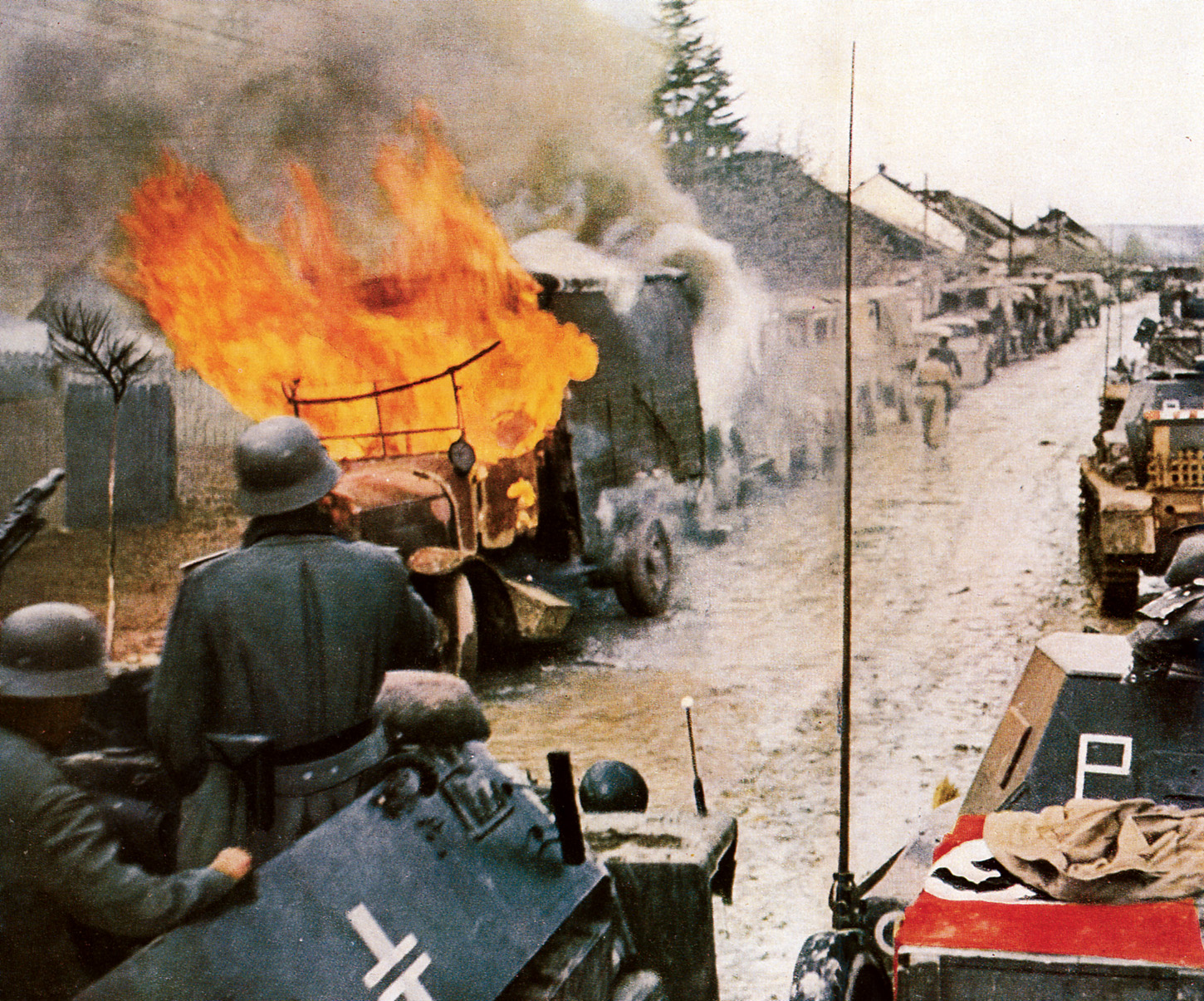

While Hitler’s panzers drove across Europe in 1941, test planes were readied for flight at Peenemunde with their new rocket engines, and soon test pilot Heini Dittmar was setting speed records of 500 and 550 miles per hour with the egg-shaped machine. He was also discovering it had major problems. The plane took off on a dolly with tires. After leaping into the air, the Me-163 jettisoned the dolly and landed on two skids, which made for a bumpy and dangerous return if it flipped on its sides or on its top. All takeoffs had to be made into a strong headwind, during which pilots had to sit passively in their cockpits. Otherwise, the Me-163 would veer off course because the rudder had no impact until the plane achieved a certain speed.

The Me-163A weighed 3,197 pounds empty, but with its 140 gallons of T-Stoff and Z-Stoff loaded, that went up to 5,291 pounds. That load gave the Me-163 fuel for four minutes and 30 seconds of powered flight. That meant that from a ground takeoff, it could hit 570 miles per hour.

On October 2, 1941, a twin-engine Me-110 fighter acted as tow plane for a test flight, hauling Dittmar’s Komet into the air. At the right time, the Me-110 loosed the Komet, Dittmar fired his engine, and it accelerated to an incredible 624 miles per hour, Mach 0.84 on the meter, setting a new speed record. It also endangered Dittmar’s life, as he lost stability and control of the plane, and it went into a steep dive. Dittmar cut the engine and glided down until he could fire it again, emptied the fuel tanks, and landed.

In Berlin, the Luftwaffe’s leaders were astounded. Even Udet, who was suffering a massive depression that would lead to his suicide weeks later, was exhilarated, demanding that the combat version of the Me-163 be developed immediately.

Lippisch was happy to oblige Udet, but there were still problems with the Komet. It kept plunging into uncontrollable dives. Pilots had no way to bail out of a damaged aircraft. The T-Stoff and Z-Stoff had a tendency to spontaneously exploding on their own. And worst of all, the prototype Me-163A had no weaponry.

The solution was to design the Me-163B, which had a slightly different engine, less prone to explosions; parachute packs in case pilots had to “hit the silk;” better ailerons to prevent uncontrollable dives; and most importantly, 30mm cannon to give it combat value.

In December 1941, Dittmar was joined at Peenemunde by another crack Luftwaffe test pilot, glider expert Rudolf “Pitz” Opitz. The pair test-flew the Me-163B during 1942, with mixed success. One flight ended with Opitz’s plane landing in a turnip field. Opitz walked away. Dittmar was less fortunate in another test: the ailerons worked, but when he landed in front of Lippisch and his team, the plane stalled at 12 feet, resulting in a crash that put Dittmar in the hospital for two years.

The ground crews had trouble with the Me-163B, as well. Known as “Black Men” for their uniforms, they had to fuel the Komet with the colorless and volatile fuels. One day a “black man” poured one fuel into a tank that still had a minute quantity of the other fuel in it, which killed him and destroyed the shed in a flash.

All through 1943, test pilots struggled with the plane, some of the flights nearly turning into disasters. Despite this, the Me-163B was accepted for production, and sklavenarbeiter (“slave laborers”) on the Messerschmitt assembly lines started punching them out.

Hanna Reitsch, the Germany’s foremost flier, was soon brought in to fly the Me-163. Reich’s aviation skills were equaled by her novelty: she was female at a time when men literally dominated the skies.

Reitsch, who had flown all kinds of aircraft, won gliding championships, received the Knight’s Cross from Hitler, and was an ardent Nazi, was a perfect choice from both a technical and propaganda standpoint. Reitsch flew four production Me-163Bs with no trouble at all, saying that it “felt like being shot out of a cannon.” But the fifth ended in catastrophe.

An Me-110 towed her Komet into the air, and at 30 feet she tried to jettison the undercarriage dolly, but nothing happened. Reitsch was unaware of this situation until the tow plane’s pilot lowered and raised his undercarriage. Hoping to boot it off, she had the Me-110 tow her to 10,000 feet, where she cast off the tow, fired the engine, and the plane developed an alarming vibration from the dolly. Reitsch decided to land, but the dolly created turbulence and made the controls ineffective. The Komet began sideslipping and stalled at 100 feet. It hit the ground with massive force, and Reitsch suffered six skull fractures and a displaced upper jawbone.

Testing went from horrifying to tragic. Lieutenant Josef Pöhs climbed into an Me-163A and gunned the engine. But the undercarriage dolly apparently fractured a T-Stoff feed line. The Komet raced up to 300 feet, banked steeply, and then plummeted like a stone, hitting the ground at an angle, and skidding along like a crab for 50 yards before exploding. Pöhs was knocked unconscious on impact and dissolved alive by the leaking T-Stoff.

But it was too late for further tests. Most of the Me-163Bs worked, British and American heavy bombers were hammering German cities and factories by night and day, and the D-Day invasion was looming. The Komet had to be committed to battle. he Luftwaffe ordered 1,000 Komets built.

The Luftwaffe formed Jagdgeschwader 400, JG 400 (meaning “Fighter Wing”), and its new Me-163Bs had ultra-short-wave radios, a jettisonable cockpit canopy, a torsion-spring pilot’s seat that could absorb 20-g, a 220-pound HWK 509A rocket motor, and wingtip skids to help keep the plane level on landing.

JG 400 got down to business in July 1944, at Brandis, near Leipzig. Its mission was to protect the critical Leuna oil refinery, one of the Reich’s most important such facilities.

Divided into two squadrons, JG 400 made its first combat appearance on July 28, attacking an American bomber raid. Their targets were B-17 bombers. The airmen of both the 454th Bombardment Wing’s B-17s and Colonel Avelin P. Tacon, Jr.’s 359th Fighter Group’s P-51 Mustangs were astonished to see the speedy contrails, but Tacon’s men put their Mustangs between the Germans and the B-17s. The Germans fired bursts at the Mustangs and then dived away. The P-51s could not keep up.

JG 400 had only 36 Komets, and their pilots were discovering that great speed didn’t help them in battle. They would approach a bomber formation at 560 miles per hour, while the B-17s flew at 220. The Germans shot by them at 340 miles per hour, which meant they had a better chance of ramming the B-17 than shooting it down. To make life worse for the Komet pilots, their 30mm cannon were unreliable and required expert marksmanship.

The JG 400 pilots tried attacking the B-17s in diving, looping, attacks, without much success. On August 5, they finally scored, with three Komets diving on three Mustangs, gunning them down at near-point-blank range.

On August 16, the “Powdered Eggs” intercepted B-17s headed for Leipzig and their escorting P-51s from the 359th. The Komets climbed to 28,000 feet and cut their motors 400 yards behind a straggling bomber. Lt. Col. John B. Murphy and his wingman, Lieutenant Cyril Jones, swung their P-51s to attack. A Komet overshot the B-17, enabling Murphy and Jones to charge in. Jones hit the Me-163 with a deflection shot that split open the canopy, Murphy, however, stayed inside the Komet’s turn and drilled it, exploding the “Powdered Egg,” the first such kill.

JG 400 pilots discovered that their planes were so fast, they could only shoot at a B-17 for two-and-a-half minutes. They had their best day on August 24, when Sergeant Schubert claimed three B-17s, and his wing-camera footage proved him correct. They were his only kills—his Komet exploded on take-off a few days later.

But the U.S. Army Air Forces had suffered enough indignities at the hands of the Komet. A week later, their B-17s pattern-bombed the Z-Stoff factory in Kiel, shutting it down.

Between August 1944 and March 1945, JG 400 only damaged a single Royal Air Force Mosquito. By V-E Day, Me-163s had accounted for a mere 16 Allied aircraft. JG 400 was disbanded before the war ended.

When the British Army drove across Germany, they captured 48 intact Komets out of the 350 produced, and the RAF took some to test as unpowered gliders at Farnborough. About 10 survived to be restored for museums. One of them went to Canada, where crews found it had been sabotaged on the assembly line by sklavenarbeiter, who had placed stones between the fuel tanks and its supporting straps, assembled the wings with contaminated glue, and written patriotic French slogans inside the fuselage.

But the Me-163 story was not finished yet. The Luftwaffe shipped a complete set of plans and an example to Japan by U-boat, and Mitsubishi engineers—who had built the legendary A6M Zero fighter—built their own knockoff, the J8M1, or “Sharp Sword,” to defend major cities. It was a faithful copy down to the Me-163 in every way. On its first powered flight on July 7, 1945, it crashed on takeoff, due to engine failure.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments