By Christopher Miskimon

Japan’s striking force sailed for Midway on May 27, 1942, a day later than planned, after some late preparations were complete. Its commander, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, requested the operation be delayed another day as well. His superior, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, refused. The attack on Midway depended on favorable tidal conditions to land the invasion force. A delay would mean postponement.

As the fleet neared Midway, problems in the Japanese system of intelligence sharing began to hamper operations. Reported sightings of American submarines were not sent to Nagumo. In one case, a submarine sighting report was not passed on because it was discounted and the staff felt it more important to maintain radio silence. Even worse, on June 3 the radio interception unit aboard Yamamoto’s flagship, the battleship Yamato, detected the call sign of an American aircraft carrier near Midway. A similar unit aboard Nagumo’s flagship failed to pick up the same signal.

Further, while the Japanese could not read American naval codes, they were able to analyze message traffic. They could determine if a message was marked urgent or routine, and they could measure the amount of radio traffic. A higher amount of radio messages could indicate more activity. Radio traffic coming from Hawaii was higher, and a greater percentage of that traffic was marked urgent. One Japanese officer even saw this and apparently notified the carrier Akagi, part of the striking force.

Further, while the Japanese could not read American naval codes, they were able to analyze message traffic. They could determine if a message was marked urgent or routine, and they could measure the amount of radio traffic. A higher amount of radio messages could indicate more activity. Radio traffic coming from Hawaii was higher, and a greater percentage of that traffic was marked urgent. One Japanese officer even saw this and apparently notified the carrier Akagi, part of the striking force.

Additional intelligence came from the Japanese submarine I-168, assigned to observe Midway. Its commanding officer, Lt. Cdr. Tanabe Yahachi, sent a report highlighting increased activity on the atoll. Between 90 and 100 aircraft sorties took off from the island each day. Many of these were Consolidated PBY Catalina reconnaissance planes, which took off at dawn and returned in late afternoon, indicating long-range missions. Work lights could be seen on Midway at night. This was much more activity than would be expected from a target which did not suspect an attack.

Taken together, these separate reports clearly indicated the U.S. Navy knew the Japanese were planning something imminent. However, no one on the Japanese staff combined these reports into a coherent narrative that may have spurred a change in plans or at least increased caution. Likewise, no one sent any of this information to Nagumo. Other shortcomings in cooperation further hampered the Japanese. The submarines which provided scouting forces were poorly coordinated, and many arrived late to their patrol areas. One submarine, tasked to rendezvous with and refuel a flying boat, arrived at the French Frigate Shoals only to find its lagoon occupied by American ships.

While the Japanese failed to assess their intelligence, the Americans prepared for the coming battle. Overnight on June 2-3, American commander Adm. Frank Jack Fletcher moved his two carrier task forces 175 nautical miles west of their original planned location, placing them 260 nautical miles north of Midway. Overcast weather greeted the American that morning, but Fletcher ordered a search by 20 Douglas SBD Dauntless dive bombers from the carrier USS Yorktown just to be sure. The two other carriers, Enterprise and Hornet, under the command of Adm. Raymond A. Spruance, kept full strike forces spotted on their flight decks.

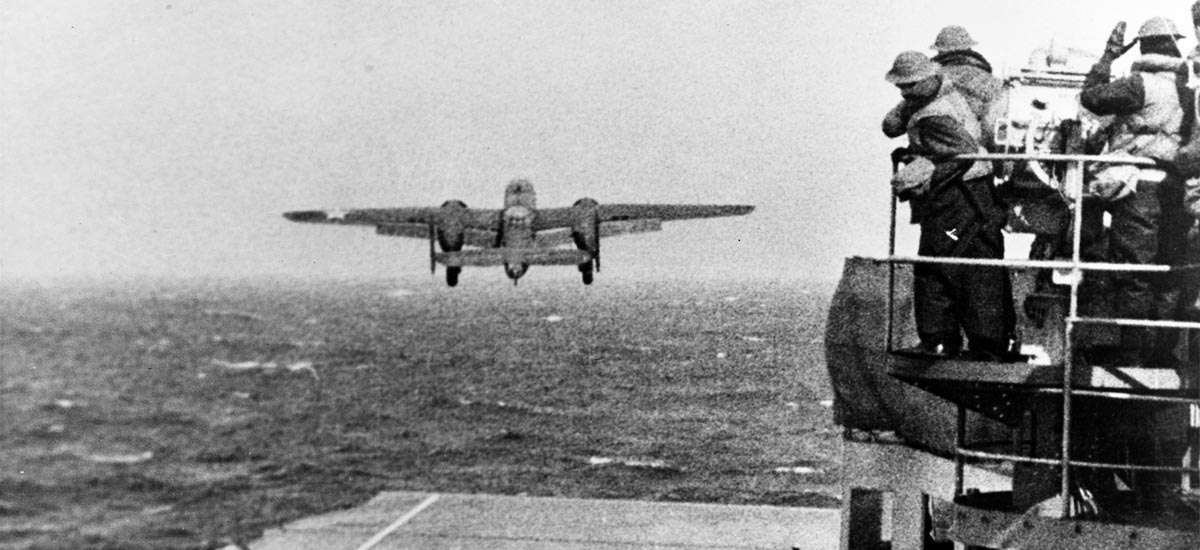

While the Dauntlesses took off for their search areas, the first indication the Japanese offensive had begun was received by the carrier task forces at 0445 hours. Japanese carrier aircraft had bombed Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Islands far to the north an hour earlier, and Catalinas from Midway were beginning to send in contact reports of Japanese ships. Unlike the Japanese in this instance, the Americans paid attention to their intelligence.

These critical occurrences affected the outcome of the Battle of Midway, a turning point in World War II in the Pacific. The combat which followed proved intense and unrelenting, each side knowing the importance of victory to their respective causes. A full accounting of this historic action is presented in Midway: The Pacific War’s Most Famous Battle (Mark Stille, Osprey Publishers, Oxford, UK, 2024, 328 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, bibliography, notes, index, $35, HC).

The author is a former naval intelligence officer and recognized authority on the Pacific War with numerous previous works to his credit. This new book provides a detailed look at the Battle of Midway using the author’s strengths. These include sober, unbiased analysis of each side’s attributes, both positive and negative, extensive research, and a clear writing style which is engaging and readily grasped by the reader. There are hundreds of books about Midway for the reader to choose from; what makes this new title stand out is the completeness of its account and its smooth narrative.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments