By Sig Unander

It is a usual evening at Club Tsubaki, wartime Manila’s most exclusive nightspot. On stage, a statuesque brunette in a clinging white dress, olive skin, and raven hair illuminated by a spotlight, is singing a “torch” song in a low, seductive voice, dark eyes flashing. Around the room Japanese Imperial Army staff officers in dress uniform listen intently.

To her admiring audience, the chanteuse is Madame Tsubaki, an exotic performer whose club provides atmosphere and entertainment. To her Filipino employees she is Dorothy Clara Fuentes—a daring, charismatic resistance leader.

One of the club’s regulars, Colonel Akira Nagahama, commandant of the notorious Kempei-Tai field office, beckons her to his table. Conversation there centers on the execution of retired American Colonel Hugh Straughn, turned guerrilla leader, at the Chinese cemetery. Straughn had shared intelligence with the club’s proprietress and was known to her.

Making conversation, the singer casually asks the colonel if he had ever seen Straughn. Nagahama grins, describing how he personally blew the condemned man’s brains out with a single, perfectly placed shot. Stifling shock and anger, she pretends to laugh. Excusing herself, she walks to the ladies’ room and is violently ill.

The flamboyant singer and spy who has thus far managed to keep her true identity from the secret police chief, is a former stage actress whose presence in Manila is an accident of fate.

Born Mabel Clara Dela Taste on December 2, 1907, in Michigan, she came west to Portland, Oregon, with her family. Her stepfather Jess worked as a ship’s engineer; mother Mable was a midwife. Early on, Clara (the name she preferred) showed a knack for performing, competing for Liberty Bonds in a patriotic pageant at age 11. A born show-off, she had a gutsy, impulsive streak. A “dare-devil,” Clara recalled, “a fighter from the word go.”

Clara entered Portland’s Franklin High School in 1922. But classes and student activities held little interest. Craving adventure, she ran away to join a traveling circus. She sold tickets to a snake charmer’s show and, when the performer fell ill, replaced him. The job was short-lived; Clara ended up back home when her mom caught up with the show.

But smitten by show business, Clara overcame parental objections and was allowed to try out for live theater. She cut her teeth with a Portland stock company, then toured. A “natural,” she could sing, dance, and act. During the Great Depression, she sailed with a musical stock unit on a tour of the Far East, ending up in the Philippines.

In Manila, the archipelago’s capital, she was performing at a nightclub when she met Filipino sailor Manuel Fuentes. They married and had a daughter, Dian, but the marriage ended and the couple divorced. Clara, now calling herself Claire, briefly returned to Portland but, before war broke out, returned to Manila and found work as a singer in a Manila casino.

Manila had been administered by the United States since the Spanish-American War but retained its colonial charm. In the summer of 1941 the Japanese Imperial Army invaded French Indo-China and prepared to move on Hong Kong, Singapore, and the Dutch East Indies. Only the Philippines—the most strategic American outpost in Asia—stood in the way.

Claire was on stage singing one evening when a tall, handsome sergeant named John V. “Phil” Phillips walked in with his buddies from the 31st Infantry Regiment. As the men slaked their thirst with cold beer, Claire delivered a sultry version of “I don’t Want to Set the World on Fire,” focusing on Phillips. “The soldier looked at me in the manner that a women longs to be gazed at earnestly … ours was a case of true love at first sight,” she recalled.

Through the fall of 1941 the new couple lived “fleeting, glorious days” in the sundrenched city, oblivious to air raid drills, blackouts, and other war preparations. Phil proposed marriage and a Christmas wedding was planned.

The storybook romance changed forever on December 8, 1941. Soon after the Pearl Harbor attack, Imperial Japanese Navy planes hit the Philippines’ Clark Field and Cavite Naval Yard, crippling American air and sea power in the Far East with a one-two punch. Claire fled the capital with Phil and her adopted daughter, Dian.

General Douglas MacArthur, knowing that Manila was not defensible, ordered his Filipino-American forces (USAFFE) to conduct a strategic retreat into the rugged Bataan peninsula across the bay, where the combined armies would hold out until hoped-for relief could come from the States.

Claire, Phil, and Dian joined the exodus of soldiers and refugees. But the danger didn’t deter the wedding. On Christmas Eve, in a makeshift chapel in the Bataan jungle, the soldier and the singer-actress became man and wife.

The Filipino-American army, weakened by disease and starvation, was struggling to hold a main line of resistance across the peninsula, so Phil told Claire to hide and wait for him. She fled to a remote mountain hideout and there met John Boone, a hard-bitten corporal who was forming a guerilla outfit. Boone asked her to go to Manila to establish a source of supplies.

Claire’s resolve stiffened when she watched 78, 000 American and Filipino prisoners shuffle by on the Bataan Death March after General Edward King surrendered USAFFE forces on the peninsula on April 9, 1942. The column of gaunt, exhausted men stretched as far as the eye could see. If a prisoner tried to get a drink or fell, a Japanese infantryman administered a head shot or bayonet thrust.

Hearing that her husband had been captured and sent to Manila, Claire slipped into the occupied city. Using forged documents and acting ability, she created a new identity: a Filipino-Italian mestiza named Dorothy Fuentes. As “Dorothy,” she volunteered as a nurse at a hospital in Malate Church, rubbing shoulders with resistance members who were smuggling aid into military prisons.

Cabanatuan was the largest camp for American prisoners in the Pacific. Conditions were appalling. Food was dirty rice slop, sanitation nonexistent, dysentery and other diseases rampant. Men did forced labor under the blazing equatorial sun. Rule violations meant beatings, torture, or execution. In this environment, even small amounts of food or medicine meant a chance to live.

Claire found work at a nightclub catering to Japanese military personnel. One night, as the club’s owner looked on, she was beaten by a customer who felt she had failed to show him due deference. As her bruises healed, she plotted revenge.

Hocking her wedding ring and American dollars, Claire leased a nearby dance studio, furnishing it and hiring her boss’s best employees to staff it. Her experience with stage sets and costumes came in handy as she transformed the space into a glamorous nightspot.

On October 15, 1942, the exclusive “Tsubaki Club” opened its doors to the cream of the occupation intelligentsia, including her ex-employer’s clients. The club featured a floor show of Asian dance routines, steamy ”torch” numbers sung by Claire, and a temple dance inspired by Hedy Lamarr in Lady of the Tropics. Guests were attended to by beautiful hostesses and white-jacketed waiters.

The grand opening was a hit and subsequent shows quickly sold out. Patrons were delighted with the entertainment, personal service, and atmosphere. The outrageous prices they paid meant huge profits—which were used to buy food and medicine on the black market. This contraband was smuggled to imprisoned Americans and to Boone’s guerrilla band on Bataan.

Claire and her hostesses coquettishly coaxed information on troop strengths and sailing schedules from boozy army staff officers and navy captains. They would sit, light their cigarettes, stroke their hair and gently encourage them to pour their hearts out. Information gathered was sent by runner to Boone, then radioed to MacArthur’s headquarters in Australia.

One day, word came that Phil had died in Cabanatuan. The devastating news incapacitated Claire. Only after a plea from a chaplain to remember Phil’s comrades who were “dying by the hundreds” was she able to continue.

The Manila underground was a diverse group: expatriates, socialites, priests, doctors, students, street vendors, and executives. Risking torture and execution at the hands of the Gestapo-like Kempei-Tai, they played a shadowy game, using code names. Claire, with a quirky habit of carrying messages in her bra, went by “High-Pockets.”

The guerillas used creative means to funnel medicine, money and messages into prisons. In the case of Cabanatuan, runners took supplies by train to a nearby town. There a sweet-faced Filipina disguised as a ragged street peddler sold bags of fruit to prisoners who were allowed into town under guard. They paid a few centavos for a bag containing several hundred pesos hidden in a false bottom. Bananas were stuffed with messages, money, or medicine. There was a separate channel for morale-building news sheets.

Once inside, contraband was distributed by trustworthy chaplains. By 1943, 30,000 to 40,000 pesos and large quantities of medicine were going into the camps every week. One grateful prisoner sent a note out to High-Pockets that read: “You deserve more gold medals than all of us in here together.”

Japanese counterintelligence, meanwhile, was tracking the guerrillas, using rewards, double agents, and torture. The most dangerous adversary was a Colonel Nagahama. An Imperial War College graduate, the bespectacled officer was brilliant and ruthless. When not enjoying floor shows at the club, Nagahama ran a relentless hunt for spies, including the elusive High-Pockets.

The strain of running a business while coordinating dangerous, complicated operations took a toll on Claire. One day she was rushed to a hospital and underwent emergency surgery. She resumed her activities, but the net was tightening. In early 1944, letters going into Cabanatuan were intercepted that incriminated American officers and resistance members. On May 23, four armed Kempei-Tai men barged into the club and arrested Claire.

Five months of brutalization in Fort Santiago followed. Claire was strapped down and water forced into her throat until she passed out. She was “revived” with burning cigarettes ground into her flesh. In another session, a nail was slowly driven under one of her fingernails.

Claire and fellow inmates were forced to kneel silently all day in cramped, filthy cells. The women endured endless nights hearing the screams of others being tortured. Two cups of rice slop a day kept them barely alive.

By fall, with her will to live ebbing, Claire pleaded with a Japanese officer to finish her investigation. He was glad to oblige. Claire was interrogated about news sheets smuggled into Cabanatuan. She denied it, even after being beaten bloody.

Soon afterward, she was given a court-martial. Charges were read before a tribunal, a plea entered, and a “guilty” verdict read. Her sentence: death by firing squad. As days dragged by, her heart pounded each time a prisoner was called. Then she was told she would have a second trial. Claire went through the motions again, bowing and pleading guilty.

Before dawn one morning, Claire was shoved into a car and driven out by the Chinese Cemetery. Convinced she was about to die, she invoked a higher power: “My thoughts jumped to my family in the States. As I prayed, a profound feeling of peace and quiet descended on me.”

The car stopped. Claire looked up. A sign loomed over a gate: “Women’s Correctional Institution.” Inside its forbidding walls a guard read her sentence: 12 years at hard labor or death if she attempted to escape.

The regimen in the Institution was extreme: forced labor on a starvation diet of rice and boiled weeds. Claire, now weighing 85 pounds, doubted whether she would see the liberation she believed was coming.

General MacArthur had promised to return to the Philippines and was making good his pledge. As the U.S. Army advanced during the autumn of 1944, word came that Japanese soldiers were executing prisoners before Americans could reach them. From her cell Claire could see vast columns of smoke and hear the sounds of combat. As the battle drew closer, tension rose. Early on February 10, 1945, a warning cry sounded. Claire dived under her bed and huddled there. Suddenly a shout rang out: “Viva Los Americanos!”

“I made a dash for the courtyard,” Claire recalled. “There stood 10 of the tallest Yanks I had ever seen. I rushed up to the nearest soldier and timidly touched his arm. ‘Yes, I’m real, sister,’ he asserted, with an assuring grin.” The GI was one of Colonel Charles Young’s 1st Cavalry Texas Rangers.

Claire and the others climbed into the colonel’s vehicles. They passed through raging firefights, inhaling the sickening stench of death. Manila suffered the worst battle destruction of any city in World War II except Warsaw as Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi’s marines fought almost to the last man, shooting, burning, and raping thousands of civilians.

Returning to Portland that spring, Claire was warmly welcomed by her family. Her extraordinary story soon appeared in Reader’s Digest and later was published as a book, Manila Espionage, bringing her national recognition.

In 1948 at Fort Lewis, Washington, Claire was personally decorated by General Mark Clark with the Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor. The written citation praised her “inspiring bravery and devotion to the cause of freedom.”

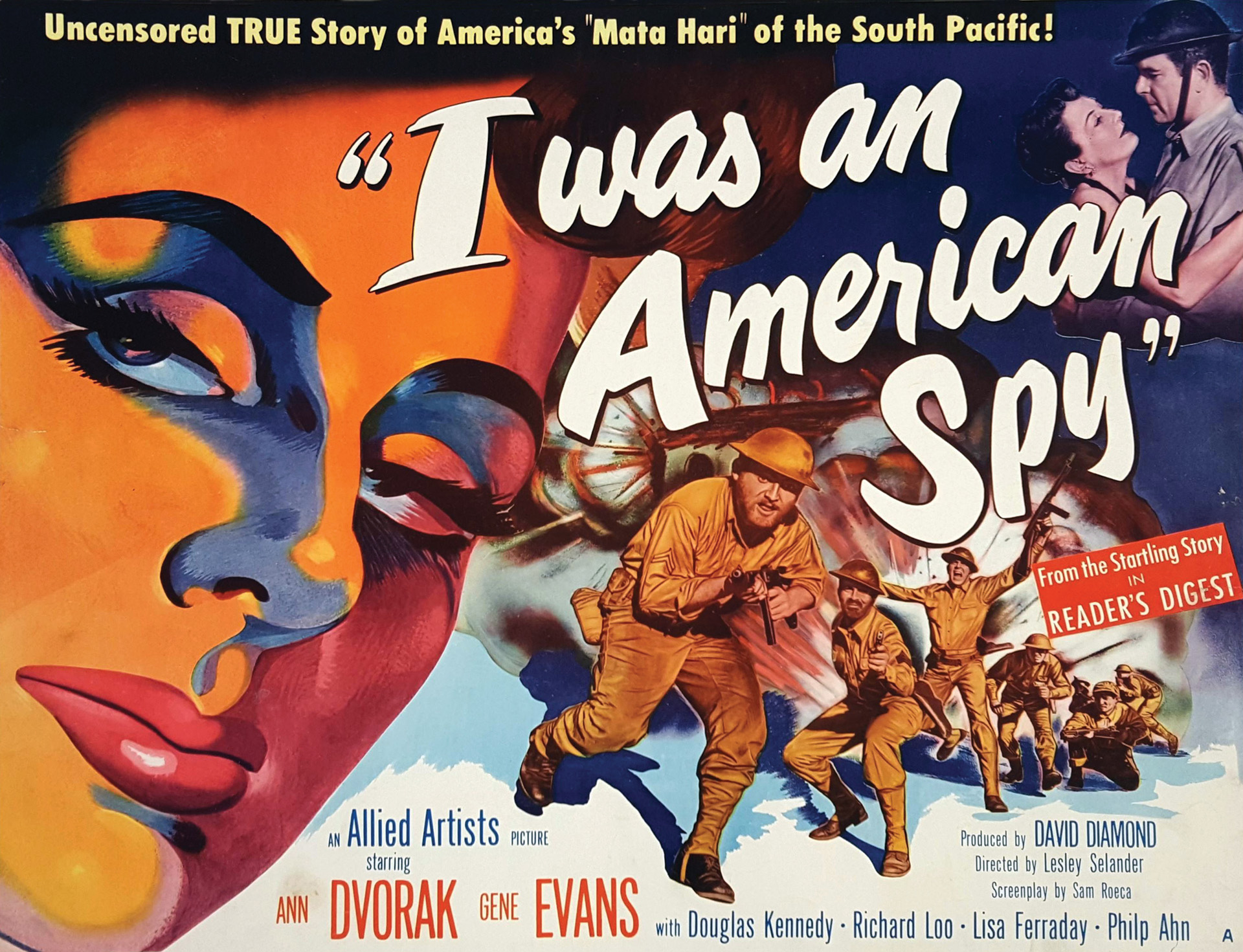

A few years later a movie—released as I Was an American Spy—based on Claire’s memoir, was produced by United Artists; classic film star Ann Dvorak played the “Manila Mata Hari.” Dvorak had also been under fire (during the London Blitz) and the two women became friends. Claire toured the country, promoting the film. She also visited hospitalized veterans and served in the Barbed Wire Club, an advocacy organization that became the American Ex-Prisoners of War.

Claire gradually found herself living a double life: public personality and working mother by day, self-medicating with liquor after hours. Post-traumatic stress and the lingering effects of torture compromised her health. She was admitted to a hospital and died unexpectedly from meningitis on May 22, 1960. She was just 52.

Today no plaque or monument honors the actress who gave her greatest performances so that others might live, but in the U.S. Embassy in Manila, a portrait of High-Pockets adorns the Claire Phillips Room, a meeting place for dignitaries. Perhaps fittingly, the portrait adjoins the chamber where Generals Homma and Yamashita were convicted of war crimes—a fate shared by her nemesis, Colonel Akira Nagahama, who was tried and hanged as a war criminal.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments