By James M. Scott

On the early evening of March 11, 1942, General Douglas MacArthur, his wife Jean, and the couple’s four-year-old son Arthur walked out onto Corregidor’s north dock in preparation to escape the battered Philippine island. Under siege by advancing Japanese forces, MacArthur’s garrison would soon fall.

Four Navy PT-boats would take the general, his family, and a few trusted aides some 500 miles south over two days to the lush island of Mindanao, where B-17 bombers dispatched from Australia would pick them up at a Del Monte pineapple plantation and fly them to the port city of Darwin.

MacArthur helped his family into the boat, where young Arthur clutched his white stuffed rabbit. The general then turned for a final look at the scorched rock fortress. “Gone was the vivid green foliage, with its trees, shrubs, and flowers,” he noted. “Gone were the buildings, the sheds, every growing thing.”

The general’s eyes fell upon his troops, who stared at him in silence. In addition to his suitcase, musette bag, and walnut cane, MacArthur would take his wife and son, the two most precious people in his life. He would leave behind thousands of husbands, sons, and brothers of families back home in America.

Families that had trusted him.

Those men would soon face the fall of Corregidor Island and the horrible Bataan Death March, followed by years of torture and beatings at the hands of the Japanese. Others would die of starvation, malaria, and dysentery, or be crammed inside the bowels of Japan’s notorious “hell ships.”

Beyond his troops, MacArthur’s beloved Manila was doomed to a brutal three-year occupation that would lead to mass starvation and even the plundering of cemeteries as desperate residents robbed the dead of jewelry, clothes, and even dentures—anything that could be bartered or sold for a few pesos to buy a fistful of rice.

This was defeat.

The general raised his cap in a farewell salute. “The smell of filth thickened the night air,” he later wrote. “I could feel my face go white, feel a sudden convulsive twitch in the muscles of my face.”

“What’s his chance, Sarge?” MacArthur heard a soldier ask.

“Dunno,” came the answer. “Maybe one in five.”

The boat pulled away from the dock and aimed out to sea. As Corregidor receded in the frothy wake, MacArthur made a solemn promise, one he would announce to reporters upon his safe arrival days later in Australia, a vow that would drive him as the weeks turned into months and then years.

“I shall return.”

For MacArthur, abandoning the Philippines was more than a tactical retreat. It was a personal loss.

The general’s father had helped capture Manila during the Spanish-American War and later served as military governor of America’s new colony. The Philippine capital, during the four decades of U.S. administration, had developed into a small slice of America in Asia, a city of Spanish colonial and elegant, neoclassical architecture intermixed with spacious parks, all set along Manila’s gorgeous bay.

Thousands of American service members, as well as employees with companies like General Electric, Del Monte, and B.F. Goodrich, called the Pearl of the Orient home, soaking up the relaxed quality of life, complete with social clubs and golf courses, swimming pools and movie theaters. “Manila is by far the most beautiful of all cities in the Orient,” the New York Timeswrote in 1932. “From the top of the University Club, it seems half hidden in a canopy of trees, green everywhere, a city within a park.”

Like his father, Douglas MacArthur’s life was interwoven with the Philippines. First posted to the islands after his 1903 graduation from West Point, MacArthur returned repeatedly, serving in greater capacities and cultivating close personal relationships with political leaders.

“In this city,” he once wrote, “my mother had died, my wife had been courted, my son had been born.” For MacArthur, the son of a career military officer who had spent his life ricocheting around world, Manila was the closest thing he had to a hometown.

“With my little family,” he wrote of his time there, “I would be lonely no more.” Many more than just Douglas MacArthur loved the Pearl of the Orient. “To live in Manila in 1941,” remembered CBS news correspondent Bill Dunn, “was to experience the good life.”

But the good life ended on December 7, 1941.

Following Japan’s attacks on Pearl Harbor and the Philippines, MacArthur ordered the evacuation of his forces to the Bataan Peninsula and the fortified island of Corregidor. He declared Manila an open city, hoping to spare the Pearl of the Orient from destruction.

In the race to reduce the family’s life into just two suitcases, MacArthur had no choice but abandon his prized library, his wife’s jewelry and family silver, and even his father’s Civil War mementos.

The Japanese seized Manila on January 2, 1942, herding thousands of American civilians into the 50-acre internment camp at the University of Santo Tomas. MacArthur endured 77 days in the tunnels of Corregidor before his departure.

During Japan’s nearly three-year occupation, the city suffered tremendously. Japanese forces confiscated warehouses of rice, sugar, and canned foods, swiped vehicles and medicines, and looted department stores. Fields rotted and the economy collapsed. Beggars swarmed the streets, many of them children.

“It is a common sight nowadays in the crowded streets of Manila that a mother, with tears in her eyes, sells her child to whoever may pay her the agreed-upon amount in cash,” one American intelligence report noted in 1944.

As many as 500 people died each day from starvation. American families, locked up behind the gates of Santo Tomas, survived off dogs, cats, and even rats, which fetched eight pesos on the camp’s black market. “I was fond of Whiskers,” internee Robert Colquhoun recalled of his pet cat, “but when the time came, I simply picked him up and presented him for slaughter.”

As commander of Allied forces in the Southwest Pacific Theater, MacArthur spent the war clawing his way north from Australia across New Guinea, each victory bringing him one step closer to returning home. When senior naval officers proposed America bypass the Philippines in the march toward Japan—a move that would abrogate MacArthur’s promise to return—the general browbeat President Franklin Roosevelt at a July 1944 conference in Hawaii.

The shocked Roosevelt, who gave in to MacArthur’s demands, retreated to bed that night, summoning his physician and demanding an aspirin. “In fact,” the president said, “give me another aspirin to take in the morning.”

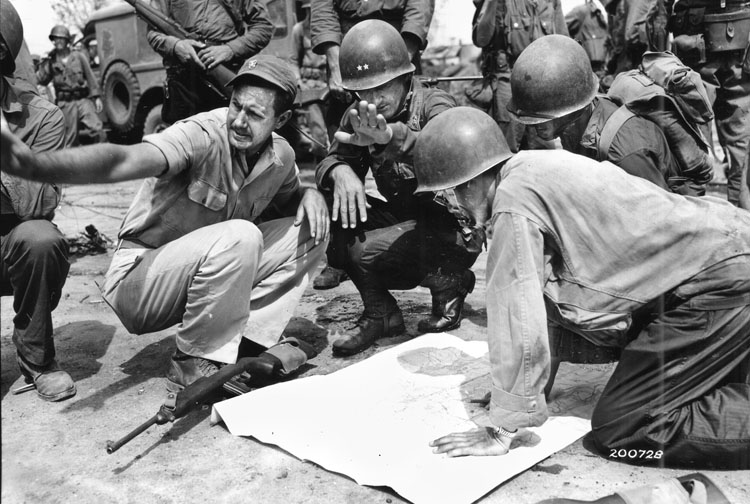

The pressure MacArthur felt reflected in the comments he made to his aides over breakfast just hours before his troops stormed the beaches of Lingayen Gulf on January 9, 1945—110 miles north of Manila and two years, nine months, and 29 days since his escape. “If the Lord will let me land this one,” he said, “I’ll never ask so much of him again.”

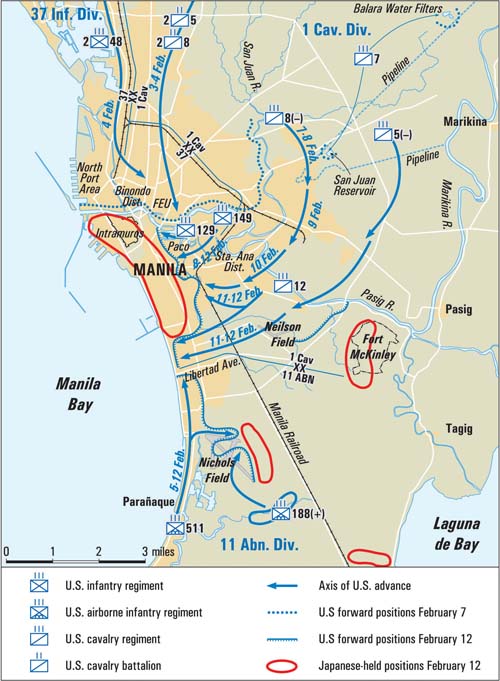

To liberate the capital—home to an estimated one million people—American war planners divided up the city. Maj. Gen. Robert S. Beightler’s 37th Infantry and Maj. Gen. Verne D. Mudge’s 1st Cavalry Divisions would approach from the north. Once inside Manila, the 37th would cross the Pasig River near Malacañang Palace and then turn west and drive toward the capital’s waterfront.

The 1st Cavalry would envelop the capital from the east, crossing the river farther south before turning toward the bay, a thrust that would parallel the moves of the infantry. The 11th Airborne Division, meanwhile, would advance from the south and close the city’s back door.

To stop MacArthur, Japan had dispatched Tomoyuki Yamashita, the 59-year-old general who earlier in the war had earned the nickname “the Tiger of Malaya” after he captured Singapore and Malaysia from the British. The general’s rivalry with War Minister Hideki Tojo, however, had prompted the latter to sideline Yamashita for much of the conflict, exiling him to Manchuria to guard against a possible Russian invasion.

But the fall of the Marianas in the summer of 1944 had led to Tojo’s ouster—and Yamashita’s resurrection. The husky general was sent to Manila with orders to turn the Philippines into a tar pit and bog down MacArthur. “The fate of the Empire,” Emperor Hirohito warned him, “rests upon your shoulders.”

But Yamashita, like MacArthur earlier in the war, had no desire to battle for the city, where the starving residents would turn on his forces once the Americans arrived. Instead, he divided his forces into several geographic commands and dispatched them to the mountains and jungles of Luzon, hoping to use the rugged landscape against the Americans.

Rear Admiral Sanji Iwabuchi, however, had other plans. As commander of the Manila Naval Defense Force, Iwabuchi’s job was to stay behind and wreck the port and waterfront in order to rob American forces of the strategic asset. Once completed, his orders mandated he abandon the city—orders he had no plans to follow.

The 49-year-old had been a failed skipper early in the war after American forces had destroyed his battleship, the Kirishima, off Guadalcanal. Iwabuchi had spent the rest of the war parked behind a desk, an insult to any seafaring officer during wartime. Only through Japan’s worsening fortunes—and the death of so many more capable officers—had Iwabuchi been given a second chance.

Iwabuchi saw in Manila a chance to redeem himself by creating an urban bloodletting similar to Stalingrad. To accomplish this, he divided his 17,000 soldiers and marines into several commands that covered northern, central, and southern Manila. Iwabuchi’s ultimate plan called for a final defense centered around Intramuros, the ancient Spanish citadel guarded by towering stone walls that overlooked Manila Bay.

Around the Walled City, Iwabuchi planned a defensive perimeter of large concrete buildings that resembled small fortresses, each built to withstand typhoons and earthquakes. Japanese troops barricaded rooms with desks, chairs, and bookcases. In the corridors, troops built staggered walls filled with dirt four feet thick and seven feet high, leaving just enough clearance over which to toss hand grenades. Iwabuchi’s forces likewise booby trapped dozens of intersections, sinking railroad ties into the pavement and converting depth charges into land mines.

Despite these defensive preparations, which Filipino guerrillas radioed to American forces, MacArthur remained convinced the Japanese would evacuate the city. The general was so confident of this fact that he ordered his staff to plan a liberation parade.

Complicating the challenge for American war planners, however, was the conflicting intelligence. In early December, guerrilla messages reflected Yamashita’s intention to abandon the city. But by January—after Yamashita left the capital for the mountains around Baguio—the messages changed, pointing to Iwabuchi’s plan to fortify Manila.

“Japs erect pillboxes, trenches and roadblock on main streets,” one message stated.

“Defensive preparation of civilian homes,” read another.

Residents watched the city’s fortification with alarm. Many who for years had prayed for MacArthur’s return now worried over the hell liberation might bring—and with good reason. “Very few of you,” Japanese troops warned, “will live to see the Americans.”

Men of the 1st Cavalry Division rolled into Manila at 6:35 pm on February 3, 1945, aiming for the University of Santo Tomas, where internees starved to death at a rate of three or four a day. During the final month of internment, the daily caloric intake had plummeted to just 572. Throngs of internees swarmed the Americans. “We went berserk with joy and excitement!” one internee wrote in her diary. “We clapped, cried, shouted, screamed, and cheered.”

But the excitement proved short lived.

That same day, Iwabuchi gave the order to begin the destruction of Manila. Incendiary squads blew the bridges over the Pasig River and swept through the city’s northern districts dynamiting buildings, a scene MacArthur’s aide, Colonel Courtney Whitney, watched unfold from a rooftop at Santo Tomas.

“Last night was a night of horror in Manila,” he wrote in a letter. “Terrific explosions from the enemy demolitions shook the city and great flames belched up thousands of feet to make it appear that the whole city was aflame.”

Major General Robert Beightler, commander of the 37th Infantry Division, vented over what he now realized was a deliberate plan to destroy the capital. “We were powerless to stop it—we had no way of knowing in which of the thousands of places the demolitions were being controlled,” he wrote in his report. “Big, modern, reinforced concrete and steel office buildings were literally blown from their foundations to settle crazily in twisted heaps.”

Infantrymen caught in the conflagration had no choice but to turn back as flames jumped from one building to the next. “Japs popped out of alleys and buildings trying to escape the fire,” recalled Captain Labin Knipp with the 148th Infantry Regiment. “We were ready and shot first. Most of the men in the lead threw grenades and charged shooting from the hip.”

Troops armed with Browning automatic rifles moved to the front. “We made quite a hole, killing every Jap we saw,” added 1st Sgt. Roy “Bus” McMurray. “At one place the fire had nearly choked off our street. We had to charge through the opening in a rush. The blistering heat and the walls of fire closing in on us had me wonder if we would make it.”

By February 7, 1945, American forces controlled the city north of the river while the Japanese held the south. With all the bridges sitting on the Pasig’s muddy bottom, troops had no choice but to cross by boat, a perilous operation. Iwabuchi’s troops unleashed withering fire, targeting the assault boats and the amphibious tractors used to recover them.

“Hollywood could not have staged the smoke, flash, and bang more dramatically,” recalled Major Chuck Henne of the 148th Infantry Regiment. “It was spellbinding to watch pieces of paddles and splintered chunks of boat plywood fly through the air while men paddled with shattered oars and rifles to work their boats to the far bank, seemingly oblivious to what was happening to them.”

Meanwhile, on the city’s southern border, the 11th Airborne Division collided with the formidable enemy defenses known as the Genko Line. The Japanese, originally anticipating an American invasion from the south, built a defensive line that consisted of 1,200 pillboxes, antiaircraft guns, and machine-gun nests that stretched from Nichols Field near Manila Bay northeast to Fort McKinley.

Adding to the challenge, the Japanese converted depth charges into land mines and buried 500-pound aerial bombs in the highways leading into the city. “From now on our advance was not measured in miles,” wrote Edward Flanagan, the 11th Airborne Division’s historian. “It was measured in yards.”

American artillery blazed a trail for the infantrymen, who fought house to house, assaulting pillboxes and bunkers with flamethrowers and demolition charges. Japanese antiaircraft shells exploded overhead, producing a rain of steel that pockmarked homes and stripped leaves and branches from trees.

“Destruction and chaos marked the path of our drive into Manila,” Flanagan wrote. “Houses and shops, flanking both sides of the highway which leads to the heart of the city, were torn up by both Jap and American artillery. Tin-roofed houses looked as though a giant can opener had sliced through them, while once pretentious mansions gauntly displayed charred chimneys and trash piles of rubble.”

The fight for Nichols Field proved fierce. The expansive open area gave the Japanese clear lines of sight on any advancing Americans. Enemy marines had fortified airplane revetments, encircled the area with barbed wire, and dug tunnels linking gun emplacements and concrete pillboxes, one of which was three stories deep and found to have a mahogany bed.

The defenders had lined the outer perimeter of the airfield with five-inch naval guns stripped off destroyed warships. The battle would ultimately drag on until February 13 before the last of the enemy at the field were destroyed. “The Japs,” Flanagan wrote, “defended Nichols Field as if the emperor’s palace itself were sitting in the center of the runway.”

By February 9—just six days after American troops entered the city—Iwabuchi realized the battle was lost. MacArthur’s forces had made it over the river into central Manila, while his defenses along the city’s southern border threatened to collapse. What had started as a fight between two armies over one of Asia’s great cities on that day devolved into one of the worst human catastrophes of World War II.

An examination of the timeline of dozens of atrocities that occurred in Manila point to February 9 as the fulcrum on which the violence shifted from individual attacks against suspected guerrillas to organized mass extermination.

Captured Japanese orders found on the battlefield—some mere fragments, others signed and dated—would later reveal that the atrocities were not random acts of unrelated violence but rather part of a systematic plan to destroy the city and annihilate its inhabitants.

“The Americans who have penetrated into Manila have about 1,000 artillery troops, and there are several thousand Filipino guerrillas. Even women and children have become guerrillas,” one order stated. “All people on the battlefield with the exception of Japanese military personnel, Japanese civilians, and special construction units will be put to death.”

That battlefield, of course, was the city.

Other orders gave instructions on how best to eliminate civilians. “When Filipinos are to be killed, they must be gathered into one place and disposed of with the consideration that ammunition and manpower must not be used to excess,” one order mandated. “Because the disposal of dead bodies is a troublesome task, they should be gathered into houses which are scheduled to be burned or demolished. They should also be thrown into the river.”

Japanese forces burned to death more than 500 people at the German Club. Troops rounded up and slaughtered another 400 males in the district of Paco, beheading 200 of them. Marines killed another 360 men, women, and children in the dining hall at St. Paul’s College.

John Lewy, a Jewish refugee from Germany, survived the massacre of more than 50 civilians inside the Red Cross Headquarters. “When I came to my senses, I thought it was a dream,” Lewy later told war-crimes investigators, “but everybody was dead.”

These large massacres often went hand in hand with scores of small-scale atrocities as marauding troops attacked families in homes and pulled others out of bomb shelters and butchered them in the streets. The Japanese went so far as to lure victims into an open lot on Kansas Street by planting a Red Cross flag. “The Japanese wanted to be sure that everybody was dead,” one survivor later told American investigators.

The attacks went beyond murder. Scores of women were rounded up and sexually assaulted at the Bay View Hotel, the luxurious property overlooking Manila Bay where Jean MacArthur once lived and enjoyed Manila’s legendary sunsets.

“I was raped between 12 and 15 times during that night. I cannot remember exactly how many times,” Esther Garcia Moras later testified. “I was so tired and horror stricken that it became a living nightmare.”

Against the backdrop of this horror, American forces pressed deeper into the city. Between Japanese demolitions and American artillery, Manila was being destroyed from the inside and out. Men, women, and children retreated below ground, where conditions inside cramped air raid shelters devolved as the hours turned to days. Bunkers built to house a single family at times held multiple. With so many bodies pressed together, the heat soared and air stagnated, filled with the noxious smells of vomit and urine.

Austrian Hans Steiner, in a letter to his mother, recounted his experience. “We lived like dogs,” he wrote. “All around us there were fires and explosions. It was the best imagination of hell one could get.”

Block by block, American soldiers battled, slowed by the fortifications at intersections, which required troops to blast their way through adjacent buildings in order to attack the rear of a pillbox.

Just as perilous were the barricaded buildings, where Japanese marines dropped Molotov cocktails and even aerial bombs from upper floor windows. “The preferred solution was to use cannon to blast the upper floors to rubble and then move in,” Major Chuck Henne recalled. “An equally favored alternative was to burn the building. When these alternatives wouldn’t work, riflemen moved in to take the building floor by floor.”

The battle for Rizal Hall, the largest building on the campus of the University of the Philippines, proved typical of the ferocious fight American troops faced throughout Manila. Japanese marines, who had fortified the passages, fought mercilessly to hold the three-story building, going so far as to try to blow up the building with both them and the Americans inside.

Neither side wanted to give ground, so as dusk settled over the city on February 22, American cavalrymen and Japanese marines prepared to share the wrecked building for the night. Iwabuchi’s marines launched an 8 pm assault on the Americans on the second floor, firing machine guns and tossing grenades.

“The holding force was engaged in the firefight for about thirty minutes, then the Japs let up for about ten minutes before launching a second attack,” the 5th Cavalry Regiment’s report noted. “This next attack was repulsed in 20 minutes, whereupon the Japs withdrew and no more fire was received from them.”

The Americans remained on alert in the darkened building, expecting another assault as soon as the moon set. The soldiers fell silent with nothing to do but wait, listen, and worry. Around 1:30 am, cavalrymen heard enemy voices at the far end of the building. “At first they seemed to be conversational tones, but gradually increased into a weird chant until there was a full chorus of singing,” recorded the cavalry’s report.

“This commotion went on for about 45 minutes, culminating in a final burst of song and loud shouting, immediately followed by many reports of exploding grenades and dynamite charges.”

The cavalrymen continued to listen. More grenades exploded. Then silence.

Detonations went off at half-hour intervals until around 4 am, at which time a lasting silence settled over the building. The following morning, an assault team moved in, counting 19 bodies in the first room, all dismembered by grenades in what the cavalry’s report described as “an appalling sight.”

But the carnage did not stop there. “In the five adjoining rooms and at the foot of the staircase were more bodies showing the same manner of death,” the report stated. “A total of 77 had completed the ritual which our troops had listened to during the early morning hours.”

American forces readied at dawn on February 23 for the assault on Intramuros, the ancient fortress that for more than three centuries had stood against invaders. An estimated 2,000 enemy troops occupied the 160-acre citadel, protected by 2.5 miles of towering stone walls that rose in places as high as 22 feet. Japanese troops had all along prepared to make a final stand in the Walled City, killing an estimated 4,000 male civilians in recent weeks who might pose a threat once MacArthur’s forces breached the walls.

Complicating any fight, war planners realized, were the hordes of women and children, some of whom the Japanese had shanghaied to serve as human shields. Furthermore, many of the civilians, who had faced starvation even before the battle began, hovered near death. In hopes of preventing unnecessary bloodshed, Lt. Gen. Oscar Griswold, commander of the XIV Corps, had attempted days earlier to convince the Japanese to release the civilians.

“Your situation is hopeless—your defeat inevitable,” the general broadcast. “I offer you an honorable surrender.”

Only silence, however, answered him.

“So,” Griswold wrote in his diary, “it is a fight to the death!”

As the sun inched skyward at 7:30 am, artillery opened fire. Reporters, many camped out in General Griswold’s command post atop a burned-out hotel just north of the river, watched the opening salvos. “I have witnessed naval bombardments,” reported Bill Dunn of CBS, “but nothing to match the concentrated fury of this barrage.”

Ten minutes passed. Then 20.

The guns thundered, each of the 120 artillery pieces an instrument in the symphony of destruction. In one hour, artillery would fire a staggering 7,896 rounds—a total of 185 tons of ordnance. That was combined with another 1,900 mortars, meaning that every second of the bombardment saw an average of three shells fired. “The old soft stones,” recalled Major Henne, “were no match for the gunpowder of modern artillery.”

The bombardment was pure terror for the civilians held hostage by the Japanese inside Intramuros, as shells pulverized the ancient stones and filled the air with thick dust, making it a struggle just to breathe. “We could not even see each other because of the smoke,” recalled survivor Benita Lahoz. “We thought that we were all going to die.”

At 8:30 am, a cloud of red smoke rose over the south wall of Intramuros, the signal for the artillery attack to end and the ground assault to begin. “The ensuing silence,” Dunn recalled, “seemed even louder than the bombardment.”

Assault boats pushed away from the muddy bank to cross the river. At the same time, artillerymen fired smoke mortars in front of the Legislature, Agriculture, and Finance buildings—all in Japanese hands—to prevent any counterattacks on the ground forces. Infantrymen charged across the burned and pockmarked golf course at 8:33 am.

Three minutes later, troops debarked from the assault boats and scrambled over the rubble into the Walled City. “As dazed, half-crazed civilians moved out of the north wall toward the boats,” Dunn reported, “our troops moved in and the fighting within the walls began.”

Inside troops found a wasted city whose narrow streets were packed with the rubble of homes, shops, and churches, forcing the infantrymen to pick through the debris. “Retaking the Intramuros,” one report noted, “developed into a small-arms duel.”

Street fighting erupted, forcing S/Sgt. Maynard Mahan to duck behind a concrete block while Japanese rounds buzzed overhead. He lit a cigarette and waited, closing his eyes for a break as he inhaled. A mortar exploded nearby, raining stone down around him. He realized then that his cigarette had vanished, stolen by a piece of flying shrapnel.

“Damn it,” he shouted. “That was my last butt.”

American forces erected a footbridge of pontoons and boards to help with the outward flow of refugees. “Over it streamed what was left of the civilian population of Intramuros. Those who weren’t emaciated from starvation bore wounds and cuts from bullets,” wrote New York Times reporter George Jones. “At intervals in this pitiful procession came Chinese carrying litters on which lay sick, wounded, or dying men, women, and children.”

The few remaining enemy troops retreated behind the towering walls of Fort Santiago, hiding in the labyrinth of tunnels and damp dungeons, forcing the Americans to ferret them out. “Every thinkable method was employed including gasoline and oil,” noted one 37th Infantry Division report. “It was effective for when things cooled and men entered these chambers, Japs were found piled high having suffered just as horrible a death as they inflicted on the thousands of innocent civilians they massacred.”

The battle for Intramuros was finally over.

For General Griswold, who had watched the fight from a battered hotel north of the Pasig, the successful capture of the Walled City came at the relatively low cost of 25 Americans killed and 265 wounded. “God has been good to me this day—and I am very grateful,” the XIV Corps commander wrote in his diary. “I am sure that the battle for Manila will soon be history. It has been a great strain and responsibility.”

Only three major enemy strongpoints remained—the Legislature, Agriculture, and Finance Buildings. “The buildings had been laboriously converted by the Japanese into individual fortresses of the most formidable type with sandbagged gun emplacements and barricades in the doors and windows covering all approaches to each building as well as adjacent ones,” according to a XIV Corps analysis. “Machine guns within the buildings themselves were sited to fire down corridors, stairways, and even inside rooms.”

Unlike earlier battles, there were no civilians trapped inside, only an estimated 700 Japanese marines under the command of Iwabuchi. The plan called for the 148th Infantry Regiment to take the Legislature and Finance Buildings, while the 5th Cavalry would seize the Agriculture Building.

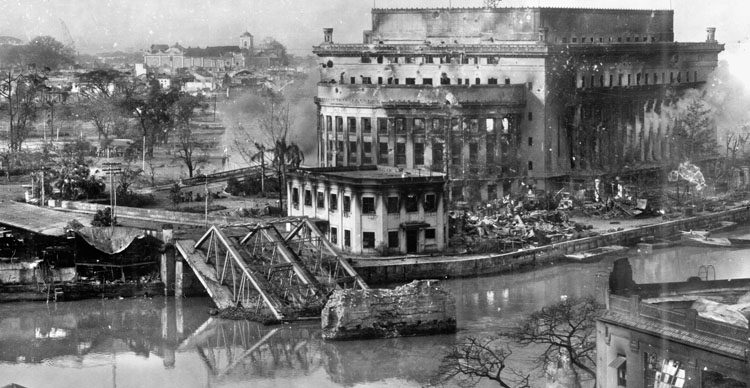

The assault kicked off with a brutal artillery bombardment. General Beightler, commander of the 37th Division, was amazed at the destruction: “We made a churned-up pile of dust and scrap out of the imposing, classic government buildings.”

Infantrymen stormed the Legislature, securing the first floor of the north wing and the first two floors of the main structure. Japanese marines in pillboxes set up in corridors and rooms poured lead on the infantrymen, killing two and wounding 52 others.

The battle ground to a halt. Artillerymen then picked up the fight, pounding the north and south wings before the infantry finally secured the building at 6 PM on February 27 in a scene best described by Army historian Robert Ross Smith: “Only the battered central portion, roofless and gutted, still stood above its wings like a ghost arising from between toppled tombstones.”

The cavalry pummeled the nearby Agriculture Building, where Iwabuchi directed the last of his marines. Initially he implored his troops to fight to the death. “If we run out of bullets, we will use grenades,” he said. “If we run out of grenades, we will cut down the enemy with swords; if we break our swords, we will kill them by sinking our teeth in their throats.”

But Iwabuchi’s vigor withered under the onslaught of American guns, which pulverized the columns and ripped gaping wounds in the concrete walls around him, exposing the building’s sinuous veins of rebar. Iwabuchi was outgunned, outmanned, and surrounded. The admiral knew he had reached the end.

In the weeks since MacArthur’s forces had charged into Manila, Iwabuchi had presided over one of the most barbaric massacres of World War II. His troops had wantonly slaughtered tens of thousands of men, women, and children in some of the most cruel and horrible ways. Survival was not an option, and he knew it.

Iwabuchi summoned his forces and apologized for leading them to doom. “If anyone has the courage to escape, please do so,” he said. “If not, please take your lives here.”

The admiral retreated to his quarters on the main floor in the northwest side of the building. Armed with a knife, he slit open his belly.

Japanese marines attempted to escape under the cover of darkness, only to fall prey to American guns. Artillery, meanwhile, hammered the building until American troops finally poured drums of gasoline into the few underground bunkers and set them on fire.

“After the number of rounds fired into this building during the past few days, it did not seem possible that any soul could be living in such a mass of rubble and twisted steel,” noted the 5th Cavalry’s report. “The entire northeast corner had been blown away leaving a gaping hole.”

Iwabuchi’s remains would never be found.

The Finance Building was all that remained. American forces broadcast an ultimatum to the Japanese, giving them just 30 minutes to surrender. During that time, at five-minute intervals, the announcer prodded the trapped enemy. “The man who stood beside you a few hours ago is now dead—what is your choice?” American forces broadcast in Japanese. “You have 10 minutes left, do you want this to be your lifetime?”

Time wound down to just 90 seconds. “At this point one Jap came literally tumbling down over the rubble in front of the building,” one report noted. “He was followed almost immediately by 12 more who advanced to our lines and surrendered.”

More emerged from a pillbox and foxhole, bringing to 22 the total who surrendered. American forces blasted away for two more days, wiping out the last of the enemy troops on March 3. “At the end,” concluded Robert Ross Smith, “the Finance Building was a shambles. The portions not knocked down seemed to be standing only from sheer force of habit.”

The Battle of Manila was over.

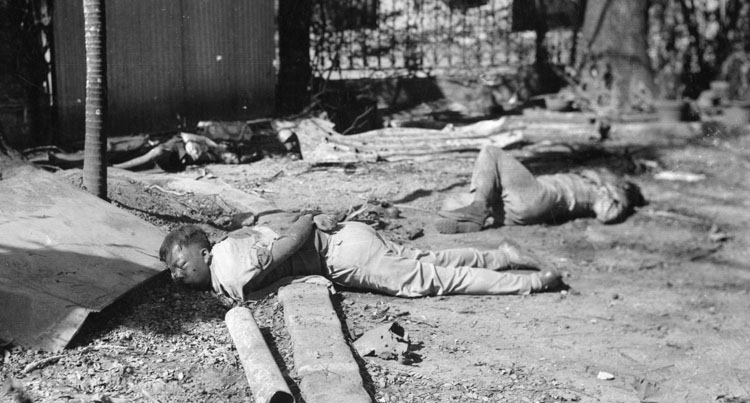

With the guns finally silent, survivors crawled out of the rubble, seeking loved ones amid the city’s wreckage. The 29-day Battle of Manila had claimed the lives of old and young, rich and poor. Artillery had vaporized many, while others died at the steel tip of a bayonet. Alongside thousands of Filipinos, the Japanese had slaughtered Russians, Spaniards, Germans, and Indians, as well as two Supreme Court justices, the family of a senator, and scores of priests. “The list of known dead that has come to my attention sounds like a Who’s Who of the Philippines,” attorney Marcial Lichauco wrote in his diary.

The fight to retake the Filipino capital had resulted in the deaths of 16,665 Japanese, the near total destruction of Iwabuchi’s forces. In contrast, MacArthur’s men suffered 1,010 killed and another 5,565 wounded. Those numbers proved a fraction of the estimated 100,000 civilians killed during the fight.

The city, meanwhile, overflowed with the wounded, who filled 32 hospitals, many of them little more than primitive aid stations set up in filthy schools, churches, and even race clubs. The carnage shocked even battle veterans like Major John Carlisle, who led a civil affairs unit tasked with rounding up medical supplies and food. “If I told you some of the things I have done and seen here in the last few days,” Carlisle said to New York Timesreporter George Jones, “you wouldn’t believe me.”

The damage extended far beyond human casualties. Japanese demolitions coupled with American artillery had flattened 613 city blocks, an area containing 11,000 buildings ranging from banks and schools to residential neighborhoods. The battle had left an estimated 200,000 homeless and destroyed countless cultural assets, from centuries-old cathedrals to sculptures and paintings inside the Philippine National Library and Museum.

“I have seen the death of a whole city,” Santo Tomas internee Robert Wygle wrote in his diary. “A new city may stand in its place some years from now, but it will bear little resemblance to its predecessor.”

One of those properties destroyed was MacArthur’s home atop the Manila Hotel, where his vast library had been reduced to ashes. Gone, too, was his son’s baby book, a loss that crushed Jean MacArthur. “You wanted to know about my apartment at the hotel,” she wrote a friend. “Of that, as well as everything else almost that I know in Manila is gone.”

At the war’s end, General Yamashita walked out of the mountains of northern Luzon and surrendered. He was put on trial in the fall of 1945 in a battered Manila courtroom, accused of allowing his forces to rape and murder tens of thousands of men, women and children in Manila and the provinces. The Tiger of Malaya denied any knowledge of the massacres, blaming the carnage on the deceased Iwabuchi.

While investigators produced no document directly tying Yamashita to the massacres, the prosecution built a circumstantial case that the atrocities were too widespread and organized for him not to have known. At a minimum, attorneys argued, he should have known. Yamashita was hanged, stripped of all decorations and even his uniform, as MacArthur ordered, on February 23, 1946.

Few cities in World War II suffered as much as Manila, which endured three years of Japanese occupation that ruined the economy, triggered widespread starvation, and shredded the social fabric. The battle to liberate the city proved an even greater nightmare. Not only did the war rob the Philippines of its capital, it also destroyed generations of families, the effects of which still ripple through lives even today, a sentiment best captured by Joan Orendain, a journalist and member of the Battle of Manila survivors group, the Memorare Manila 1945 Foundation.

“By the end of the war, we had nothing,” recalled Orendain. “All we had was our memories—death’s stench, the hunger, the blood, the terrible sounds of bombs, grenades, and bullets, the great fires, the odor of charred bodies and charred wood, and the eeriest sounds of all—the whistling of a bomb about to hit, and the keening over the slain, in its aftermath. We hear those sounds today as clearly as we heard them then.”