By Susan Zimmerman

In an age before television and instant communications, Americans wanted to see what was going on in the world’s “deadliest conflict in human history,” and LIFE magazine was making a name for itself as THE war magazine during World War II. The news weekly did its part by filling its pages with top-notch photography.

LIFE magazine’s youngest war correspondent and photojournalist in the Pacific Theater at that time was 24-year-old Ralph Morse. His wasn’t a household name yet, but his war photographs would soon be on newsstands and in homes throughout America.

Growing up in the Bronx, New York, with humble roots, Morse wanted to be a newsreel cameraman but when he realized he couldn’t afford to join the union, he decided to take every free photography class that the City College of New York offered in the late 1930s. When it came time to look for work, he opened a New York business directory and started working his way through the alphabet. He landed his first job when he reached “P”—with photographer Paul Parker. Morse’s life became a Horatio Alger rags-to-riches photographic success story.

After working for Parker, Morse exhibited early on his knack for being in the right place at the right time. While working in a photo lab as a printer with co-worker Cornell Capa (a future war correspondent and brother of famed LIFE photographer Robert Capa) at the New York photo bureau, PIX, Morse’s picture-taking prowess caught the eye of one of the bureau’s owners, Alfred Eisenstaedt, the legendary LIFE photographer who took the famous image of a soldier and nurse kissing on V-J Day in Times Square.

Morse recalled what turned out to be the launch of his career: “My friend Cornell Capa, who worked in the lab at PIX, said we need another lab guy, so they hired me. That Sunday I went out to Jones Beach and took Cornell’s 35mm camera. I saw some guy playing with a kid on the beach, throwing him in the sky and I took pictures. When I showed the photos to the salesman at PIX the next morning, he said, ‘I’ll sell these in a half hour.’ He sold them 30 times the first day and then he says, ‘You better just read The New York Times and cover things and we’ll sell [the pictures].’ In the meantime, Eisey [Morse’s nickname for Eisenstaedt] kept saying to Wilson Hicks, the photo editor at LIFE, ‘You better meet this new young brat we’ve got.’ Finally they called me.”

In 1940 or 1941, LIFE offered Morse, who was then just 22 years old, a part-time job—10 days a month. Then, when war broke out, LIFE hired him full time in February 1942. Immediately Morse was thrown into the combat action.

During Morse’s years covering both the Pacific and European Theaters and the postwar reconstruction of Europe, he embodied a “Kilroy was here” presence [the graffiti character popular with GIs in the 1940s]. Like Kilroy, Morse “made his mark” wherever he was sent. He “was there” for Jimmy Doolittle’s 1942 take-off for the raid on Japan, the Marines’ landings at Guadalcanal, the Battle of Midway, the Normandy invasion, Patton’s drive across France, the liberation of Paris, the surrender of the German armies to Eisenhower, Nazi Party leader Hermann Göring’s war-crimes trial at Nuremberg, and the list goes on. Morse was as much a part of history as the history he documented.

During the decades in which Morse took pictures, he captured some of mankind’s most important moments through his lens, and his habit of “being there” followed him well into his civilian photography. He was there in 1948 to capture the cancer-stricken Babe Ruth’s last day in a Yankee uniform; in 1955 to immortalize the moment when Jackie Robinson stole home in the World Series (using a missile-tracking camera to fire a hundred feet of film at 10 frames per second); and in 1958 at the beginning of the American space program, which he went on to cover for the next 30 years, becoming especially well known for his technical innovations. Morse worked as a staff photographer for LIFE from 1942 until 1972, and then at Time magazine from 1972 through 1988 covering everything from sports to space.

Although over 70 years have passed since the onset of World War II, the 96-year-old Morse, in his exuberant, still-youthful voice, brought the past to life with his vivid recollections of his war correspondent days in a recent interview exclusively for WWII Quarterly.

“When World War II started, I was going down to Fort Rucker, Alabama. Of course, when I got to the airport and heard the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor, I just cancelled my plane and went back to New York.

“In the office was a member of the Secretary of the Navy. He wanted to form a task force led by Cecil B. DeMille [by then a well-known Hollywood movie director]. He said, ‘You guys will be made petty officers and go anywhere we send you to do a history of the war on film.’

“I spoke to Wilson Hicks, the managing picture editor of LIFE, and I said, ‘This is fine, except one thing: someone could tell us what to do. I said I should think about this.’ Hicks said, ‘No, I think you should become a war correspondent. You’ve been covering the build-up of the military and therefore you have all the credentials needed to be a war correspondent,’ and [he said] you have to join LIFE’s staff. In those days war correspondents were staff people. So that’s what I did and that’s how I became a war correspondent.

“My first trip, I got on a plane and went to Pearl Harbor, got a hotel room, a Hertz car, money in the bank from LIFE magazine, all the things you had to do. And then, when I reported in at Pearl Harbor, they said, ‘You can go on the next task force.’ I said, ‘Sure, that’s what I’m here for.’ I left Pearl Harbor on the carrier Enterprise with Admiral [William F.] Halsey and didn’t know where we were going or what we were doing.

“About two days out, Admiral Halsey made the announcement that ‘Tomorrow morning you’re going to see the Hornet [aircraft carrier] with a bunch of Army bombers on deck. We are not delivering bombers; we are going to take these as close as possible to Japan, and they are going to try to bomb Tokyo.’ And that’s how I got onto the Doolittle Raid.”

Morse in the Pacific Theater

Morse remembers his next assignment aboard the heavy cruiser USS Vincennes at Guadalcanal and the Battle of Savo Island:

“We were going south but they don’t tell you where you’re going or what you’ll be doing. So we pull into Pago Pago and the harbor is full of troop transports. I ask the captain of the Vincennes, ‘Can I go over to the Marine general,’ and he says yes. So I go over there, tell the general who I am, and that I’d like to go and land wherever they are going. He says, ‘Do you have the proper clothing,’ and I say no, I have nothing. In the Navy you have a pair of khaki pants, and sneakers, and t-shirt and a life preserver. I said I do not have landing equipment. He says, ‘Don’t worry about it, the Marines will supply you the high shoes, clothing, the gas mask, water bottle; the supply guy will give you everything.’ I stayed on the ship to Guadalcanal and landed with the Marines in the third wave.

“Our objective the first day on Guadalcanal was to take the airport and we [did]. Afterward I went back to the beach to go [and get a ride] out to my ship, because the Vincennes was out in the harbor there. It had all my film, all my clothing; everything was on the ship, because you can’t land with it.

“So I had the Navy take me back out and the captain said to me, ‘Well, go get yourself a shower. We can’t send you back to the beach tonight because of the fact that we are not sure in the dark what part of the island we own. I will get you back ashore first thing in the morning.’

“I gave the chaplain on board the film and said, ‘When you get to San Francisco, take this to the Presidio, and ask for censorship; I don’t know how long it will be before I get out of here; you’ll be there in four days.’ But I never got the shower or food. We went to general quarters, and that was the battle of Savo Island and that is where we got sunk.

“The Japs came around the island and fired 8-inch guns directly at us. By the time we got organized to fire back, we had pieces of our boat missing. We might have got hit by a torpedo too, but that is not what sunk us [the Vincennes]. We were sunk just by 8-inch guns. I was in the water for six hours waiting to be rescued. My film of the landing of the Marines went down with the ship.

“Back in Pearl Harbor, I asked Admiral [Chester] Nimitz about returning home to get equipment. He said, ‘You realize you will be the only one except the War Department and President who knows about that sinking.’ So he said, ‘Let me think.’ About an hour later he says, ‘You can do it, but you have to promise you won’t tell anyone about it,’ and he gave me orders to go back home.

“When I got to the LIFE offices, they said, ‘What you are doing here?’ I said I need new cameras. They asked what happened; I said, ‘I can’t tell you.’ This went on with my draft board, too. They asked, ‘Why should we give you orders to go overseas again?’ Then one morning I walk into LIFE, expecting another day of being told no, and they said to go over to Brooks Brothers to buy clothes and order camera equipment.

“I go over to my draft board and they said here are your papers. I had my orders. When I got back to Pearl Harbor, they said Admiral Nimitz wants you. I went in and said, ‘I didn’t talk,’ and he said, ‘I know. We deal with Commander Adams; he is Naval Intelligence. He was with you the whole time and he saw what they were doing to you. You couldn’t talk so he shut them up.’

After getting new equipment, Morse returned to Guadalcanal because, as he said, “I wanted to get back to the island to photograph the boys on their first Christmas away.”

It was during a patrol when Morse came across a Japanese skull propped up on a tank. His image of an incinerated, severed Japanese head—one of the most horrific photos ever published—appeared in LIFE’s February 1, 1943, issue, and is considered the first gruesome picture released by the Office of War Information’s censors. [In September 1943 another horror image followed with George Strock’s image of three dead American soldiers on Buna Beach.] Morse recalls the story behind the skull incident on Guadalcanal:

“We went on patrol. This was with the Army. It was right at Christmas time. The Marines had pulled out so the Army took over. The patrol was up through the woods. The brush was so thick, if you lost sight of the man’s foot in front of you, you were lost. Now we came across this opening in the middle of this wooded area. There on a tank was a dead Jap’s skull.

“The sergeant in charge of the patrol said, ‘Look, nine out of ten chances this is a booby trap. The Japanese probably have mortars aimed here for American soldiers to come in and kill them.’ So he says we’ve got to be careful. ‘The men here are all going to run like hell and get through it. You, come up, take your picture, and run like a son of a bitch back to us.’

Covering Patton’s Third Army

Morse then contracted a bad case of malaria at Guadalcanal, so he was sent home to a New York hospital. After recuperating, he was assigned to Europe to cover Patton’s Third Army in 1944.

“I was with Patton crossing France. He was in the news so much that I did a cover on Patton for LIFE [January 15, 1945].

“Then a most unusual assignment came from LIFE headquarters: The next week I get a telegram from New York saying, ‘We’d like you to be with a guy when he gets hurt [and then] stay with him all the way till he gets back to the States.’ I read this thing and thought, an ambulance only holds four people; they’re not going to let me go.’

Morse remembered the necessary strings that needed to be pulled to accomplish this six-week-long, 4,500-mile assignment:

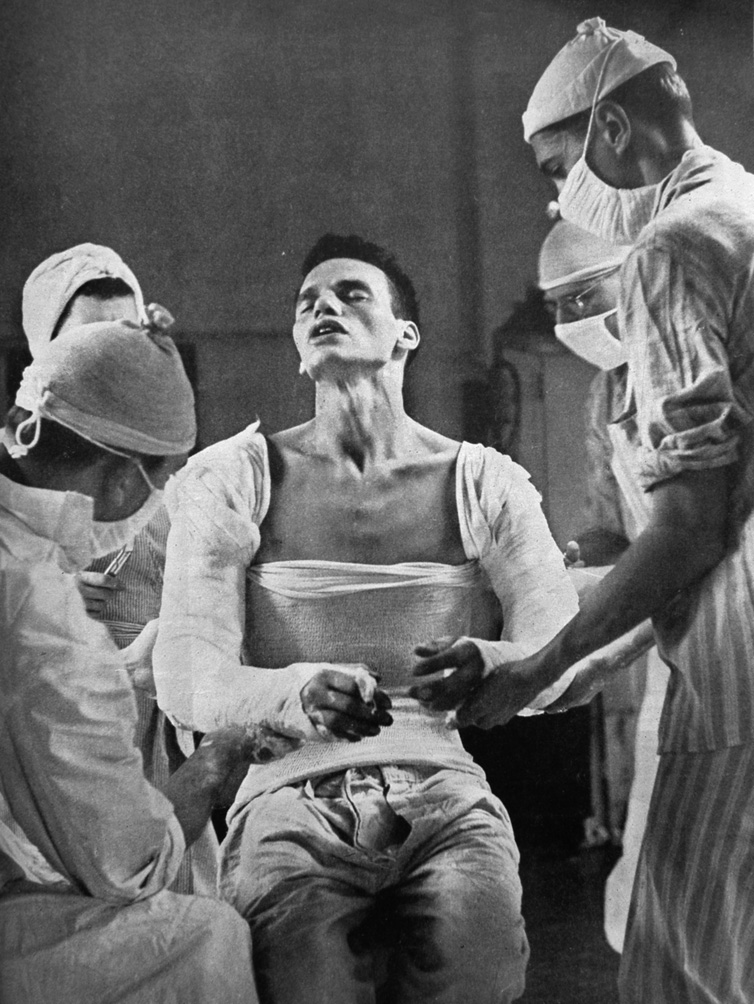

“I walked over to Patton’s office and asked, ‘Can I see the general?’ They said, ‘Of course.’ Patton said, ‘Look Ralph, no one is going to let you do this story. There is only one way. Tell LIFE to go to the Surgeon General of the Army and give you a set of orders that you are a wounded man equal to the man you’ll be with; that gives you the right to be with him at all times.’

“Then later on Patton called me in and said, ‘I got this message from Washington and they have agreed to this story; they like the idea. I will inform all the military hospitals in the whole area so that everybody knows about you and your story when you pick the guy. I’m going to send out 30 sets of orders and I will court-martial anyone who gets in the way.’ That is how we did the George Lott story.”

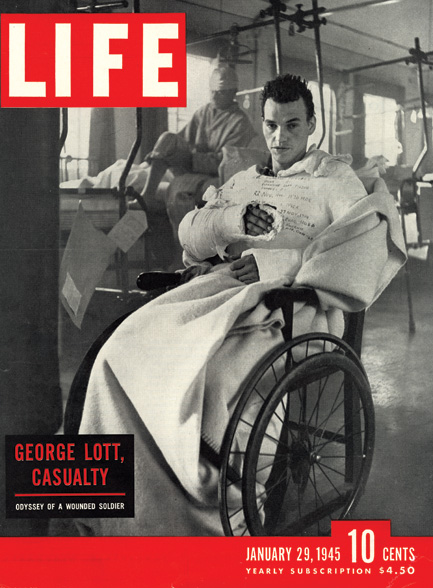

Ralph was on the scene minutes after George Lott, a 22-year-old American medic, was wounded in both arms by German mortar fire on a battlefield in northeastern France. Morse snapped a series of photos—from Lott being evacuated from the field, to the field hospital, to his surgery, and back in the United States for further treatment and eventual recovery. The story appeared in LIFE’s January 29, 1945, issue.

Morse gained a reputation for doing whatever it took to get the picture–– whether it was following a wounded man from the battlefield to the hospital or sleeping on the floor for two days at the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Forces in Reims, France, while waiting for the Germans to sign the surrender documents. He recalled:

“I went across Europe with Patton and covered the surrender of the German Army to Eisenhower. I was a civilian photographer doing it for the whole world; there were military people, but I was the only civilian. Then I went on to Nuremberg to cover [Hermann] Göring [at the War-Crimes Tribunal].”

The Road Back Home For a POW

While Morse’s images most often exposed the brutality that came from battle, there were moments off the battlefield where Morse captured some of war’s tender moments. Here he recalls the one photo he considers the most beautiful, which he writes about in his self-published memoir, The 8th Astronaut:

“I have no answer to the question of what is my favorite picture, but, for sure, my photo of the French prisoner of war walking home is the most beautiful shot I’ve ever taken. In 1944, I was sent to a labor camp in Germany to choose a prisoner and follow him home. I chose a most friendly Frenchman, August St. Andre, a railroad worker from a small French town, isolated from his family for five years, who had been forced to work on German jeep motors.

“Transportation proved to be the technical challenge of this story. Even though I accompanied him on his route from the German camp to his French village by train, bus, and foot, my car full of camera equipment needed to be dragged along, necessitating my backtracking every couple of hours to bring forth the auto.

“However, all our efforts to capture his long journey home were in vain. Instead, LIFE started the printed story with his homecoming, leading with the exquisite photo of his walking the last leg home after we exited the bus. The story showed his daughter Marie Louise’s running a kilometer down the road to greet her father, and then moving her father to tears singing him a sentimental song.…”

More than seizing the history of the moment and the news of postwar Europe, this picture with its cobblestone street, horse-drawn carriage, and converging trees is a most beautiful piece of art. Enveloped in this one photo was St. Andre’s return from an ordeal—and his entire homeward trek.

A Career in Photography After WWII

After Morse started working for LIFE, photography became his life and a dream come true. Following the war years, he began covering the fledgling U.S. space program in 1958 and continued for the next several decades. His intense coverage of the Mercury 7 astronauts earned him the moniker, “The Eighth Astronaut,” a nickname bestowed upon him by astronaut John Glenn, the first American to orbit Earth. Morse’s inventiveness really took flight in 1962 when, with the help of NASA, he mounted cameras on everything from rocket tails to umbilical towers. Along the way his cameras were sometimes smashed, incinerated, and “unofficially” launched.

In 1969 Morse filmed the launch of the Apollo 11 mission—the first mission that landed humans on the moon, and in 1998 he was on scene to shoot Glenn’s return to space. Morse recalled, “On John’s second space flight, I did not have cameras; I hadn’t taken a picture in eight years.” Morse, who was 81 at the time and long since retired, remembered telling his editor that he no longer owned a camera. “LIFE said to me, ‘Nobody knows John Glenn except you; we’ll send you down the equipment.’”

In 1995 Morse received the Joseph A. Sprague Memorial Award, the highest honor in the field of photojournalism, according to the National Press Photographers Association, and in 2010 he received the Briton Hadden Lifetime Achievement Award for his World War II photography. During a speech honoring Morse for his 30-plus awards, George P. Hunt, LIFE’s managing editor from 1961-1971, said, “If LIFE could afford only one photographer, it would have to be Ralph Morse.”

To single out just one of the magazine’s celebrated photographers was an extraordinary statement but Ralph Morse was an extraordinary photographer. Looking back on his career as one of the leading photojournalists, the 96-year-old Morse said from his Florida home:

“You have to remember I covered so many events in World War II because you could do it if you were a war correspondent. You couldn’t do it if you were a member of the military because someone could say you can’t go there if you’re in a uniform and he’s a higher rank. But if I’m in a war correspondent “uniform” and they say you can’t go; then you say go to hell and just do it; that’s the important difference.”

All honour to a brave and dedicated man. Ralph Morse’s pictures have been with me constantly throughout my 45 years as a Kiwi history teacher. I wonder now what myself and my students would have done without his so truthful pictures and stories. Iconic records indeed!