By David H. Lippman

It was the storm that forced the battle. On June 19, 1944, a massive gale hit the English Channel, sweeping in from the west, hitting the gigantic artificial harbors the Allies had built on their D-Day invasion beaches. By daylight on the 20th, the artificial roads and piers had disappeared under waves that reached eight feet high. For three days, the storm tore at the British breakwaters off Arromanches and the American ones at St. Laurent-sur-Mer, destroying the American harbor entirely and badly damaging the British piers. More than 140,000 tons of supplies were destroyed, and 800 ships lost or beached.

When General Omar Nelson Bradley, who commanded the U.S. First Army and later the 12th Army Group, visited the battered artificial harbor, he wiped sea spray from his eyes and kicked the sand in frustration. “Nothing pained us more than the beaches. Each day the deficit mounted until we fell thousands of tons in arrears, especially in ammunition.” Down to three days’ supply of ammo, Bradley postponed his drive south until the port city of Cherbourg was taken. In the meantime, ammunition would be rationed, if necessary.

The general strode around the ruined harbor and said to a naval lieutenant, “Hard to believe a storm could do all this.”

The lieutenant responded, “General, we would much sooner have had the whole damned Luftwaffe come down on our heads.”

The losses were greater than anything the Germans had been able to inflict on the Normandy beaches with their V-weapons, bombers, and midget submarines, and the Allied offensive now seemed stalled. The Americans were down to two days of ammunition, and the British were three full divisions short. Only a fifth of the planned quantities of supplies could be landed on the remaining artificial harbor on the British invasion beaches. A replacement harbor was urgently needed. The nearest one was Cherbourg. Without it, the invasion of Normandy might fail.

Cherbourg: Crucial Harbor in Normandy

The capture of Cherbourg had been a central factor in the planning of the invasion of Normandy since the site had been chosen in 1942. The famed harbor had been used by Atlantic freighters and passenger liners ranging from tiny coal boats to the massive Titanic. It had been a mile off this harbor that, in 1864, the Union warship Kearsarge defeated the Confederate raider Alabama during America’s Civil War. The latter ship had been preying on Union merchant shipping in the English Channel.

Now, with its piers, docks, and cranes, Cherbourg was the logical first target port to be seized after the Allies came ashore in Normandy on D-Day, June 6. Everyone who could read a map could see that. The problem was, Adolf Hitler could read a map, too.

With the Americans streaming in through the bocage country, driving across the Cotentin Peninsula, headed straight for Carteret and the opposite Baie du Mont St. Michel, it was obvious that the American strategy was to cut off Cherbourg from reinforcement, then move on the isolated port city and seize it from the rear. Just as obviously, Hitler was determined to defend Cherbourg like every other position he might lose: to the last man and last bullet.

Von Schlieben’s Defenses

To do so, Hitler ordered Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Schlieben, who commanded four divisions on the peninsula, to hold Cherbourg. If he could not, the city had to be captured as a “field of ruins.” Schlieben, described by his later British interrogators as an obedient toady, went straight to work.

Von Schlieben had the parts of four divisions under his command: the elements of his own battered 709th Infantry Division, which had originally held Utah Beach; the 243rd Infantry Division, which held the west coast of the Cotentin Peninsula; parts of the 77th Infantry and the 91st Air Landing Divisions, which had been cut off by the American advance; and other odd outfits: the 30th Mobile Brigade, the Seventh Army’s tough mechanized Sturm Battalion, two battalions of French R35 and S35 tanks (training outfits that had been activated after the invasion), battalions of nebelwerfer rocket artillery, and a variety of fortress command units in the city itself, including a battalion of German Marines.

Most importantly, von Schlieben had under his command a fairly modern fortress in Cherbourg itself. The city was surrounded by a ring of hills upon which the Germans had deployed strongpoints with machine-gun, antitank, and 88mm gun emplacements, along with tank barriers. Behind that stood older French forts that had held up the Nazi offensive of 1940, now reinforced with heavy guns and German engineering. The guns were a mixed bag—one battery consisted of two captured British 3.7-inch antiaircraft guns, part of the loot at Dunkirk. Batteries named “Querqueville” and “Hamburg” could fire out to sea with 280mm shells that could damage American and British warships sent in to provide covering fire.

Lee McCardell, covering the advance for the Baltimore Sun newspaper, wrote, “So-called pillboxes in the first line of German defenses … were actually inland forts with steel and reinforced concrete walls four or five feet thick. Built into the hills of Normandy so their parapets were level with surrounding ground, the forts were heavily armed with mortars, machine-guns, and 88mm rifles. Around the forts lay a pattern of smaller defenses, pillboxes, redoubts, rifle pits, sunken … mortar emplacements permitting 360-degree traverse, observation posts and other works. Approaches were further protected by minefields, barbed wire and anti-tank ditches at least 20 feet wide at the top and 20 feet deep. Each strongpoint was connected to the other … by a system of deep, camouflaged trenches and underground tunnels.”

Even so, the Germans had key disadvantages. Most of the 21,000 defenders came from second-line divisions and lacked both equipment and determination. The 709th had very few vehicles and had been battered since D-Day. A fifth of the defenders were Polish and Russian former prisoners of war who had put on the German uniform rather than starve to death in Nazi POW camps. One Russian, who commanded several such “Ost” units, when drunk admitted to “wanting a bit of plunder.” Supplies were short, air cover nonexistent, and every road could be hammered by ubiquitous American and British fighter-bombers or warships.

Nonetheless, Cherbourg would not be an easy nut to crack, and in charge of the offensive would be one of the U.S. Army’s best leaders, Lt. Gen. J. Lawton “Lightning Joe” Collins, who had already won his spurs by defeating the Japanese on Guadalcanal. Now this veteran of two amphibious campaigns was leading the U.S. VII Corps, heading north to crush the defenders of Cherbourg.

Three Divisions Under Lightning Joe Collins

Collins had three divisions available: the veteran 4th Infantry, which formed the first wave at Utah Beach; the 9th Infantry, which had fought in North Africa; and the new 79th Infantry, which was as well trained and equipped as the other two. All were backed up by independent tank battalions, plenty of artillery, squadrons of fighter-bombers, and warships from the U.S. and Royal Navies offshore, including the massive battleships USS Texas and USS Arkansas, whose 14-inch guns could crush the fixed German coast defenses.

Collins was the son of an Irish Catholic immigrant who wound up in New Orleans as a Union drummer boy in the Civil War. Born in Algiers, Louisiana, Collins got into West Point through his uncle, political boss and longtime New Orleans Mayor Martin Behrman. A member of the class of 1917, he was appointed chief of staff to Lt. Gen. Delos Emmons, who replaced the luckless General Walter Short as commander of the Hawaiian defenses. Collins got his brigadier general’s star in February 1942, and command of the 25th “Tropic Lightning” Division in May 1942, leading the Army on Guadalcanal. His superb performance gave Collins command of VII Corps and the invasion of Utah Beach, which was highly successful.

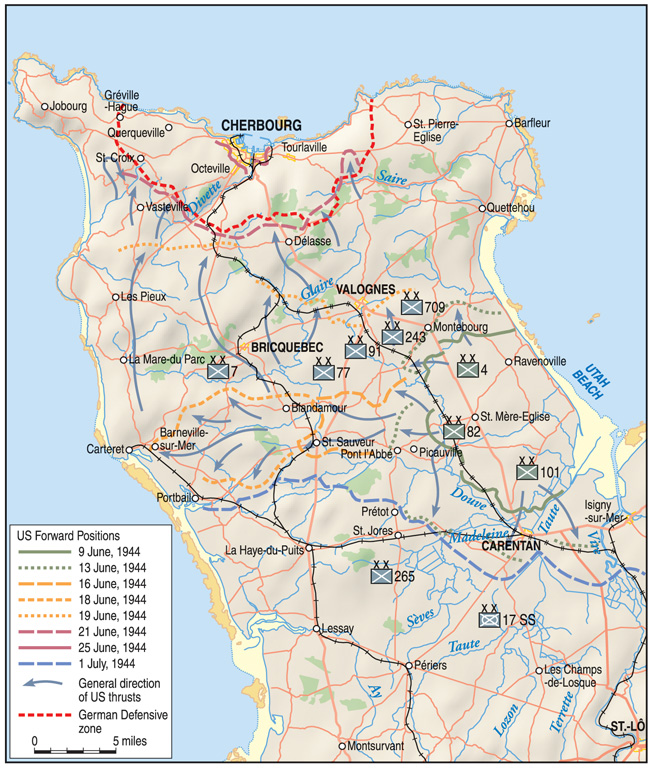

Collins was ahead of the storm and the game. Two days before the storm hit, he was planning his attack on Cherbourg. His plan was to line up his three divisions: the 9th on the left, the 4th on the right, and the 79th in the center, and grind up the peninsula to the city, with the two veteran divisions acting as pincer hammers with the 79th as the anvil in the center. Cherbourg would be attacked from three sides, with naval support. Simple and deadly attrition would do the job.

Assault on Cherbourg

The attack went in on the 19th, ahead of the storm. The 9th Infantry attacked on the left, sweeping through the German defenses quickly, reaching their objectives at Rauville-la-Bigot and St. Germain-le Gaillard before noon. The 4th Cavalry Regiment faced a little more opposition but reached its objective of Rocheville. To hold the gap between the 9th Infantry and the 79th, Collins borrowed the 1st Battalion of the 359th Infantry Regiment from the 90th Infantry Division. So far the 90th had performed poorly, but this battle might give the division’s men a chance to shape up.

Major Randall Bryant, executive officer of the 1st Battalion, led his men, surprising himself and his team by bouncing a bazooka round off a road and into the belly of a German tank.

By mid-afternoon, the 9th Infantry was ready to continue the attack and moved ahead with the 39th Infantry Regiment reaching Couville and the 60th reaching Helleville. That evening, the 4th Cavalry Regiment entered St. Martin le Gréard. The 9th Infantry was doing well.

Meanwhile, the 79th attacked from its line of Golleville to Urville, and its 313th Infantry Regiment reached its objective, the Bois de la Brique, west of the small city of Valognes, against slight resistance. The 315th was supposed to bypass Valognes, but resistance held it up. The 79th contained the city from the west.

The veteran 4th Infantry Division headed north backed by the 24th Cavalry Squadron, which screened the right flank. The Americans jumped off before daylight, anticipating having to face the tough Sturm Battalion and the 1,000-odd men of the 729th Regiment. Private William Jones, of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, helped dig out Germans holding on near Montebourg. “They would lay there and fire at you until they ran out of ammunition and they would jump up and surrender. They were real dedicated people,” he said later.

Shermans Against German Anti-Tank Weapons

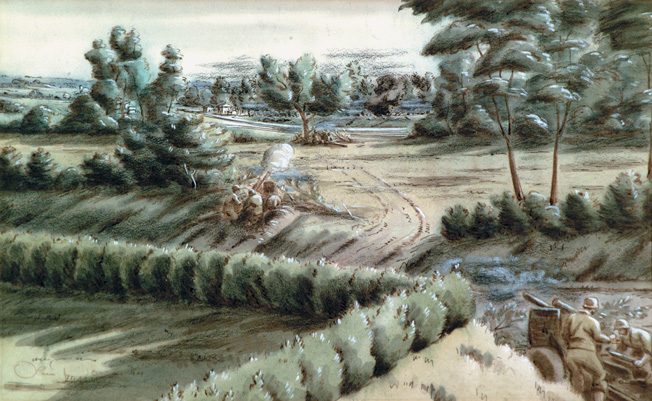

The Germans fought back from deep entrenchments, and it took until dawn before the attack could continue with tank support. When the Sherman tanks showed up, the Germans withdrew. Company B, 70th Tank Battalion, circled the Germans from the rear, battling concealed antitank guns.

Bob Knoebel, a gunner in a lead Sherman, said, “We were going from one side of the road to another, and our tank was instantly on fire. In fact, I glanced in back of me and flames were already up in the air, just that quick.”

Knoebel bailed out and slid down the sloping front of his tank, landing on the road. Just ahead, German soldiers brandished their weapons and beckoned Knoebel and his lieutenant to become prisoners. Knoebel and his lieutenant ran away instead, reaching another tank, whose commander urged Knoebel to join his crew. Knoebel slipped into his gunner’s slot, and the tank rolled out, trying to flank the antitank gun that had knocked out Knoebel’s old tank.

Instead, Knoebel’s new tank was hit by German panzerfaust antitank shells, which knocked it out, and Knoebel was hit in the legs. He crawled into a nearby ditch, but the Germans finally captured him.

Private Harper Coleman, a D-Day veteran, also in 3rd Battalion, 8th Infantry, said, “This was the way it was for most of the time, one hedgerow to the next on your stomach, or lower, if you could. Many incoming shells to all sides and Burp … guns all the time. We would advance some distance and bog down when no one could go forward. After some time there would be the next order to start another attack. This went on day and night.”

Streets Strewn With Rubble

By 6 pm, the 8th Infantry Regiment was near Valognes, and the 22nd entered the deserted town of Montebourg. The 22nd Infantry found the city destroyed and civilians—dirty, frightened, and bewildered—hiding in cellars.

“They are living in the most extreme poverty,” wrote Lieutenant John Ausland to his family. “Clothing as such is unknown. All they have are rags. Dirty berets are the most common head dress for men. Women’s dresses are torn and dirty.”

The streets were so rubble choked that engineers had to bring up bulldozers to clear them. Engineer Sam Ricker said, “When we entered Montebourg, there wasn’t anything there but rubble. It was our job to clean the roadways out. Most of the time we took a bulldozer and they moved all this debris to the sides where trucks and jeeps and different vehicles could advance.”

The 4th moved along through the heavy storm that pounded the D-Day beaches. “The rain and wind made conditions unbearable for the men in the field,” one soldier wrote.

But the weak German resistance was not a sign that they were collapsing. Von Schlieben was carrying out his orders to withdraw to Cherbourg, offering just enough resistance to keep the Americans moving slowly.

That the Americans did. On June 20, the 4th Infantry finally popped out of the murderous bocage country and into Valognes, finding the city choked with rubble but the Germans gone. It was worse than Montebourg, and the bulldozers took several days to clear the roads. They kept moving until they reached their objective at the Bois de Roudou, just in front of the main German defense line.

Two regiments of the 79th also headed north up the N13 highway until they hit the main German line. The Germans fell back so fast that the Americans captured four intact light tanks and an 88mm gun at one point and eight more tanks at another.

188 Tons of Supplies

The 9th Infantry had a harder time, intending to cut off the most northwesterly part of the Cotentin Peninsula, the Cap de la Hague, which was perceived as a possible last-stand area for the Germans. The 60th Infantry’s advance was rapid until noon, when heavy German artillery fire stopped the veteran 60th Infantry from reaching its initial objective, Hill 170.

The 1st and 2nd Battalions attacked abreast north and south of the Bois de Nerest and came under heavy German fire from 88mm and 20mm guns. Lt. Col. James D. Johnston, commanding 2nd Battalion, was mortally wounded by shellfire. Maj. Gen. Manton Eddy, who commanded the division, altered his plan and attacked to the north, taking positions on the crossroads formed by the junction of the les Pieux and Cherbourg roads. With those arteries in hand, the Americans tried to turn east but were stopped in their tracks. “Road marches were over,” wrote official historian Gordon Harrison. “Hard fighting lay ahead.”

The VII Corps now faced a belt of concrete and field fortifications in a semicircle four to six miles from Cherbourg. With their usual thoroughness, the Germans covered every approach route into the city, with antitank obstacles in stream beds and antiaircraft guns configured for land defense. To defend these entrenchments, von Schlieben formed Kampfgruppe Mueller, under Lt. Col. Franz Mueller, using pieces of the 243rd Division. This outfit held the line from Vauville to Ste. Crois-Hague. Next came the 919th Infantry Regiment and the 17th Machine-Gun Battalion under Lt. Col. Guenther Keil. Next was the 739th Regiment under Colonel Walter Koehn and then the 729th under Colonel Helmuth Rohrbach.

The defensive positions were strong; the troops, however, were inferior. Some battalions were down to 180 men. Von Schlieben told his bosses that he needed three full divisions with tanks and regular resupply to hold Cherbourg. He had none of the above. At least he had plenty of ammunition for immediate needs, and the German Navy tried to help out, delivering supplies by E-boat and U-boat, while the Luftwaffe used 107 transport planes to drop 188 tons of supplies into the besieged perimeter.

Cherbourg Encircled

As rain and wind poured down on the front, the Americans used June 20 and 21 to tighten up the line and reorganize. From extensive aerial reconnaissance, the French Underground, and radio intercepts, the Americans had a fairly complete grasp of the German defenses.

Meanwhile, the 4th Infantry continued to move ahead, trying to cut the main road from Cherbourg to St. Pierre-Eglise, but German resistance kept them 500 yards short of their objective, Hill 158.

On the 21st, the skies cleared and the 8th and 12th Infantry Regiments attacked northwest into the main Cherbourg defenses, heading for high ground 800 yards northwest of Bois de Roudou. The 8th first had to clear out V-1 launching sites and found the defenders very determined, holding out in concrete shelters. The 1st and 3rd Battalions fought their way out of the woods, and the 2nd Battalion brought in tanks to finish cleaning out the defenders. Some 300 prisoners were taken in the attack.

The 12th Infantry was stopped by a blown bridge, so it halted for the day. By end of the 21st, Cherbourg was sealed off, with all three U.S. divisions ready to attack. With supplies short and the American artificial harbors, codenamed Mulberry, wrecked, taking Cherbourg was even more vital. Collins told his men that the attack was “the major effort of the American army.”

“It Was Really a Hellhole”

That night, Collins tried diplomacy to take Cherbourg. He broadcast a surrender demand to the defenders in German, Russian, Polish, and French, giving von Schlieben until 9 am on the 22nd to capitulate. Von Schlieben did not answer the request.

To rip up the German fixed defenses, Collins called for the IX Bomber Command and the British 2nd Tactical Air Force to hammer the defenders. After the British Hawker Typhoons and North American P-51 Mustangs did their job, the Ninth Air Force’s Lockheed P-38s and Martin B-26 Marauder bombers pounded the German strongpoints.

The American plan called for the 9th and 79th Divisions to attack into the city while the 4th Division sealed Cherbourg. The 9th Division’s objective was Octeville to Cherbourg’s west, while the 79th would grab Fort du Roule, the Vauban-style French-built fort that garrisoned the city’s southern approaches. H-Hour was to be 2 pm.

At 12:50 pm, the RAF attacked, their Typhoon rockets creating an incredible din for 20 minutes, which cost the British 24 fighter-bombers to flak. Then wave after wave of American heavy bombers roared in, 375 in all, hammering the German fortifications with armor-piercing bombs and high explosives.

Lieutenant Gabriel Greenwood, a 27-year-old fighter pilot in the 405th Fighter Group, described the defenders’ antiaircraft barrage: “It was as though the earth had erupted and spread … up into the sky through our planes. I never saw so much flak, tracers, flares, or felt so many concussions before.” Nonetheless, Greenwood made his attacks. “It was really a hellhole. A battlefield in all its awful magnificence.”

The American pilots struggled through flak and smoke created by the earlier attacks and had trouble spotting targets. Lieutenant Edward Michelson, zooming along at 300 mph in his P-38, saw a scene of chaos. “The ground fire was so intense it seemed the only safe place to be was below treetop level.”

Another pilot, Captain Jack Reed, got his plane filled with shrapnel. “We were on the deck in a ravine and all hell broke loose,” he said. He saw two P-38s near him get turned into fireballs in seconds.

Lieutenant Alvin Siegel of the 358th Fighter Group dropped his bombs on gun emplacements and then saw a truck on a road as he pulled out. “I peeled off and dove,” he said. “At that altitude I just barely had enough time to line up on the truck, squirt a short burst of fire and pull up immediately. I had to pull up right away to keep from going into the ground. I looked around and the truck was burning mightily and black smoke was curling up into the air. There must have been some type of munitions in the truck that made it burn so black.”

But the attacks were not all successful. There were numerous “friendly fire” incidents, and by 1:30, forward American positions were asking that the air attacks be stopped. The fighter attacks ended at 2 pm when the troops went forward.

The medium bombers hit the Germans blind to provide the attackers with a rolling barrage. The bombers smacked the Germans but also hit their own troops, making the 9th Infantry suspicious of close air support for the rest of the war.

The bombing did little good. While it disrupted German communications, killed German soldiers, and kicked up a lot of gun positions, it did not pulverize the defenses. The attacks were neither well coordinated with the advance nor accurate.

Breaking the German Defenses

As a result, all three divisions made slow advances against the German defenses, which showed ample determination. The 47th Infantry headed for Bois du Mont du Roc, while the 60th headed for Flottemanville. The Americans bypassed defenders, relying on their practiced “holding attack” tactic. In this, one battalion would engage defenders and pin them down, while a second and third moved around to cut the Germans off. It worked, but it was slow work. “It became necessary to destroy these prepared positions one by one,” the division historian wrote.

Private First Class Dominic Dilberto’s I Company of the 39th Infantry found the air force had done its job in their sector, discovering dead Germans in a blasted position. “Their bodies were bloated, black and emitted a sickening stench,” he said. “This area was dotted with huge coastal emplacements. In one such pillbox, we found a dazed German officer just sitting there waiting for us. He was our first prisoner.”

Dilberto and his crew were lucky. Pfc. Lloyd Guerin, a replacement in the 9th, was assigned to deal with a sniper whom a tank had just flushed out. “He might as well have told me to build a stairway to heaven,” Guerin said later. “I didn’t know what to do.” He and a pal crawled 100 yards up a ditch. “I looked back and the other guy wasn’t there. When I got a little further the sniper stopped firing. I don’t know what happened—either someone shot him or he left. But the tankers said it was okay, so I went back. The squad leader asked me what happened, and I said, ‘Job completed,’ or something like that.”

The 79th Division moved forward, three regiments abreast, up the N13 highway, and ran into a strongpoint that straddled the road at les Chevres. The 3rd Battalion of the 313th Infantry attacked the strongpoint on the left, while the 1st attacked frontally in the usual holding attack, which broke the German line. Next came the German fortified antiaircraft position at la Mare a Canards, and the 313th had to stop there.

The 314th fought in draws east of Tolelvast until dark, when a battalion slipped around the Germans. Here, the 314th was a few hundred yards from the main German Army switchboard but did not know it. The bunker was not discovered, and for a day or so the Germans had an excellent observation post right behind American lines.

The 79th relied on artillery fire to blast holes in the German wires and communications, but the larger forts were impervious to even large-caliber shells. Lieutenant Bryon Nelson, an artillery forward observer, called in fire on the German pillboxes. “The 155mm projectiles literally bounced off the pillboxes,” he said. The Americans had to dig out the Germans by crawling under their fire, and relying on satchel charges, grenades, and flamethrowers.

McCardell told his Baltimore newspaper readers that the typical American soldier “hadn’t had his shoes off in a week. His feet were killing him. He would have given $10 for a clean pair of 10-cent socks. Aside from canned rations, he carried only what he wore plus his canteen, a shovel, an ammunition belt, an extra bandolier, a knife, his bayonet, and his rifle.”

At one point, Colonel Bernard B. MacMahon’s 315th Infantry faced a major defensive position at Les Ingoufs. A Polish deserter showed MacMahon that the guns there had been destroyed, so MacMahon gambled on psychological warfare. He brought up loudspeakers to demand a German surrender. Out came large numbers of German soldiers, waving white flags, arms raised. A group of five German officers followed them, asking if MacMahon could save German honor and everybody’s lives by firing a few phosphorous shells into the position so their commander could feel he “had satisfied his obligation to the Führer and surrender.”

MacMahon had no phosphorous shells. Well, how about five phosphorous grenades? MacMahon could find only four. They were duly tossed into a cornfield, and the garrison and field hospital surrendered, sending 2,000 German, Russian, and Polish POWs into the bag.

“You German SOBs, You Killed My Buddies”

The 4th Infantry had a tougher time, attacking toward Tourlaville with confused fighting. The Germans mounted infiltrating counterattacks into the rear of the American forward battalions. The 22nd Infantry was surrounded for a while and had to fight to keep its supply routes clear. On the left flank, the 8th Infantry had to capture high ground east of La Glacerie in the triangle between the Trotebec River and its main tributary. The 8th came under heavy fire from Germans behind the ubiquitous Normandy hedgerows and artillery. It lost 31 killed and 92 wounded. Treebursts tore men apart.

Lieutenant John Ausland called in fighter support, but the 12 Republic P-47 Thunderbolts that answered the request missed La Glacerie’s emplacements. “The Germans simply came out of their dugouts after the bombardment was over and started firing. Later in the day, with the help of tanks, the battalion captured the stronghold and took over 60 prisoners,” he said. “While some of the guns had been destroyed by air bombardment, most of them were intact.”

The victory upset Lt. Col. Carlton McNeely, who commanded 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry. One of his subordinates, Captain George Mabry, found McNeely sitting behind a tree, head in his hands, crying. Mabry sat next to McNeely and asked what was wrong.

“George, it tears me up to see so many of our fine young men being killed like that,” McNeely said.

Mabry agreed but urged McNeely to put his feelings aside and say, “You German SOBs, you killed my buddies, I’m going to get 10 more of you for that. We cannot afford to let the death of our friends affect us so much because it will affect our ability to fight and lead.”

McNeely saw the point. After talking for a while, he regained his composure.

The 12th Infantry had a tough time, too. Lieutenant Ralph Hampton, a forward observer, said of the hedgerow country, “You couldn’t see more than 50 yards. You had to use a map to know where you were. The map had lines on it for each hedgerow—looked like a spider’s web. Those hedgerow battles were very severe, with ‘screaming meemies’ and poor observation.”

The Americans struggled to defeat well-concealed antitank guns and defenders lying in wait with panzerfaust rocket launchers, the first disposable antitank weapon. The German panzerfaust crews blew up Sherman tanks before the Americans knew the Germans were there. Clarence McNamee, a tank crewman in B Company, 70th Tank Battalion, saw one of his company’s tanks take a direct hit from an antitank gun. The tankers abandoned their vehicle and ran behind it, which was the wrong thing to do. The next German shell hit the tracks of the damaged tank and killed the crew members. “It was sickening,” McNamee said later. “While killing became second nature, this was a friend. He had played accordion for us just the night before.”

“It is Your Duty to Defend the Last Bunker”

The American advance on the 22nd was slow against desperate and determined German resistance, but Collins saw signs the Germans would crack. A lot of POWs were coming in, including some of the odds-and-sods that Von Schlieben had to use for defense: labor troops, military police, coast artillerymen, and Russian and Polish “volunteers” who had little desire to lose their lives against Americans.

Some Germans endured. One teenager from the Reich Labor Service wrote of the bombing, “An inferno descended—roaring, shattering, shaking, crashing. Then quiet. Dust, ash, and dirt made the sky gray. A horrific silence lay over our battery position.”

Von Schlieben knew the game was probably a loser, too. But Hitler tried to buck up his spirits with a harsh message on the 22nd, which read, “Even if the worst comes to the worst, it is your duty to defend the last bunker and leave to the enemy not a harbor but a field of ruins … the German people and the whole world are watching your fight; on it depends the conduct and result of operations to smash the beachheads, the honor of the German Army and of your own name.”

Von Schlieben was not impressed. He reported to Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, his boss at Army Group B, that his men were exhausted in body and spirit, the port garrison was over-aged and undertrained, and many men were suffering from verbunkert, or bunker paralysis, being unwilling to fight outside their ferro-concrete positions. Many of his troops from the 77th and 243rd Divisions lacked leaders and were mostly drains on his food and ammunition supply. Von Schlieben signaled, “Reinforcement is absolutely necessary.”

Rommel pondered what to do. He toyed with shipping the tough 15th Parachute Regiment from Brittany to Cherbourg by E-boat, lighter, and U-boat, but Allied naval supremacy shut that down. He pondered airdropping in the paratroopers, but they had not trained in that role, nor did Rommel have enough Junkers Ju-52 transports to do the job, and the droning tri-motored planes could not penetrate the Allied air umbrella either. The best the Luftwaffe could do was to parachute in bags of Iron Crosses that von Schlieben requested to present to his men. Cherbourg was on its own. At least von Schlieben and the Allied air force were doing the job Hitler wanted, blasting the port into ruins.

Hard Fighting For the 4th Division

Next day saw heavy fighting. All three divisions moved in through wrecked towns and villages. The 9th Infantry’s 39th Infantry Regiment cleared fortified positions west of Beaudienville, which had been bypassed. The 47th Infantry stormed Hill 171, capturing 400 prisoners. The Americans were now inside the outer defense ring, standing astride the ridge leading to Cherbourg. The 60th Infantry waited out a long-delayed artillery bombardment on Flottemanville and captured the town with little resistance. The 79th kept moving up, working around German defenses, battling German infiltration parties.

The 4th Division did not reach its primary objective of Tourlaville but made progress with its tank support. The American Shermans rolled into fields and steamed over German riflemen, which broke their will and resistance. The 3rd Battalion of the 8th Infantry launched its attack just as the enemy was about to launch its own, which enabled the Americans to rout the concentrated Germans with heavy fire.

The 4th Division had a hard day. Lieutenant Paul Massa, another forward observer, was operating with the 1st Battalion of the 12th Infantry. On the morning of June 23, he and his men were advancing about a hundred feet behind armor of the 70th Tank Battalion. The Sherman tanks sprayed the hedgerows with machine-gun fire. Suddenly there was an explosion, and the lead tank was hit. “The tank stopped, his motor roared like it had slipped out of gear, and then the lid of the turret flew open and the crew scrambled out. All except one man. He was trapped inside, and I heard his screams as he burned to death.”

Later, Massa found himself lying in a ditch sweating out an artillery bombardment when he found, of all things, a newspaper clipping that showed a photograph. “The caption told how Mrs. Natalie Pugash and her daughter of Tampa, Florida, were making a victory garden, while 1st Lt. Joseph Pugash was serving overseas with the Army.” Massa was pleased—Pugash was a pal from Artillery Officer Candidate School and in a nearby unit. Massa hung on to the clipping. Moments later, Massa’s radioman, Corporal Fishman, hopped into the ditch, and said, “Lieutenant Pugash is dead. His body is on the other side of this hedgerow.”

Massa said later he felt like he had been hit over the head by a sledgehammer. “If Fishman had said that my own brother was dead, it would not have hit me any harder. By this time, I had seen too many dead friends. I couldn’t bring myself to go look at Joe’s body.”

By dusk, the Americans had moved into the outer ring of the Cherbourg fortress, and von Schlieben knew the score. He radioed on the morning of the 24th that he had no more reserves and ordered his men to fight to the last cartridge. The fall of Cherbourg was inevitable. “The only question is whether it is possible to postpone it for a few days.” He also requested additional Iron Crosses with which to decorate his men, and more bags full of the medals were parachuted in by the Luftwaffe.

On June 24, the VI Corps continued to close in on the city. The 9th Division overran three defended Luftwaffe installations. German fire was heavy, but when the American infantry came up, defenses crumbled. The 47th Infantry helped the 39th capture an antiaircraft emplacement, then turned north to the old French fort of Equeurdreville, and the German battery north of it, the Redoute des Forches. They got there by dusk but postponed the attack until daylight.

The 314th Infantry attacked with support from dive-bombing P-47s to clear la Mare a Canards and move within sight of Fort du Roule. Three attempts to take the fort were frustrated, but the 313th, on the flank, cut down resistance west of La Glacerie and Hameau Gringot, hauling in 320 prisoners and several artillery pieces.

The Cherbourg defense was starting to collapse under the sheer weight of American firepower and the efficiency of American holding attacks, but the Germans continued to show their expertise in last-ditch stands, especially in the east against the veteran 4th Infantry. East of La Glacerie, German light artillery, antiaircraft guns, and mortars threw back the first American attack. The Americans tried again with tank support, and the Germans pulled out, another one of their specialties.

“Combat Efficiency Has Fallen Considerably”

The 8th Infantry lost 37 killed, including the commander of the 1st Battalion, Lt. Col. Conrad Simmons. The 12th Infantry also lost the commander of its 1st Battalion, Lt. Col. John W. Merrill, who had taken over the battalion only the day before. At Digosville, the Germans held an artillery position, so the Americans called in 12 dive-bombing P-47s to winkle them out. The Germans withdrew, leaving behind six field pieces because they were unable to move them. Tourlaville was occupied without a fight that evening, and the 12th Infantry hauled in 800 POWs.

Lieutenant Massa walked away from other survivors at Tourlaville and studied the route of advance. “Fragments from large-caliber shells mutilated and mangled human bodies. Dead men had huge holes through their bodies, and arms or legs torn off. One man was in a sitting position, with the top of his head neatly removed. The inside of his head was empty, as though everything had been scooped out,” he said later.

Von Schlieben’s new report to his bosses read, “Concentrated enemy fire and bombing attacks have split the front. Numerous batteries have been put out of action or have worn out. Combat efficiency has fallen off considerably. The troops squeezed into a small area will hardly be able to withstand an attack on the 25th.”

Next morning saw the U.S. and Royal Navies enter the battle, with three battleships, four cruisers, and screening destroyers trading salvos with the German coastal batteries.

At 4:30 am, the warships, battle ensigns snapping, steamed into action behind minesweepers. The English Channel was now dead calm after the storm. “The sea was glassy smooth under light airs, which barely increased after daylight,” wrote naval historian Samuel Eliot Morison. “There was a light haze which, as the ships approached the French coast, was enhanced by smoke from artillery fire and demolished bomb targets, blown over the water by an 8-knot southwest breeze.”

With Consolidated B-24 bombers and Grumman TBM Avengers flying antisubmarine patrol to the west and P-38s overhead for top cover, the warships bore down on three key batteries.

Then came the wait to fire or be fired upon. The Americans were not to fire until noon unless requested or fired upon, to avoid friendly fire incidents. But the Germans did not open up. Finally, the Germans opened fire at 12:05 pm, attacking the minesweepers. HMS Glasgow and HMS Enterprise, two light cruisers, answered back, and at 12:51 a German 150mm shell smacked into Glasgow’s port hangar. Four minutes later another hit her after superstructure. She pulled out of line, but Glasgow continued to fire on the aggressor, Battery 308, hurling 318 rounds of 6-inch shells to temporarily silence the Germans.

At 12:12, the battleship Nevada, a veteran of Pearl Harbor and D-Day, opened fire with her 14-inch guns, and 18 rounds later got the word from her spotter plane, “Nice firing. You are digging them out in nice big holes.” Ultimately, Nevada would fire 112 rounds of 14-inch and 985 rounds of 5-inch shells.

The bombardment went on for 90 minutes, with the British and American warships suppressing the German batteries. The Querqueville battery seemed to have a charmed life, surviving the fire of a battleship and four cruisers. Rear Admiral Morton L. Deyo, commanding the force, was amazed at the large number of near misses, and a sailor on the cruiser USS Quincy remarked, “It’s just like throwing rocks at a bottle—no matter how many you throw, you can’t hit it.”

Artillery Duel With Battery Hamburg

The battleships Texas and Arkansas took on Battery Hamburg, and it seemed every hummock and hill had a German gun. The battery consisted of four 280mm (11-inch) gun turrets with powerful armor, protected by six 88mm antiaircraft guns. Texas and Arkansas traded rounds with the German battery, and a German shell hit the destroyer Laffey—it turned out to be a dud, and the damage control team pried it loose and hurled it overboard.

One of the hidden advantages the Americans had in the battle was the German use of slave labor in their factories … the sklavenarbeiter had no desire to see Germany win, so they sabotaged production as much as possible, often filling shells with sand or dirt instead of gunpowder.

Another shell hit the water on the destroyer Barton’s shoreward side and ricocheted into her hull, ripping through bulkheads. This 9.4-inch (240mm) shell also turned out to be a dud.

Soon both sides were blazing at each other. Battery Hamburg next nailed the destroyer O’Brien, when a 280mm shell sheared away the ladder to her bridge, scattering her signal flags and ripping into her combat information center. It killed 13 men and wounded 19. O’Brien’s skipper was Commander William Ward Outerbridge, who had commanded the destroyer USS Ward in the famous duel with the midget submarine at Pearl Harbor. He turned his ship north immediately and avoided further damage with help from a good smoke screen.

Taking three quick hits and near misses on battleships, the Americans and British decided to open the range. The Germans still tried to do damage. A gust of wind cleared the smoke screen away from Texas.

A Saturday Evening Post correspondent, Martin Somers, wrote, “A destroyer begins to lay a smoke screen. The destroyer just ahead of us gets four near misses. Water spouts high around her. An 11-inch shell misses us by 300 yards, but the enemy’s shooting improves rapidly. Four near misses … bracket us. We’re hit below the water line on the port side twice, but the 6-inch shells bounce off the heavy armor. The fierce blast of our own guns mingles with the explosion of near misses from the batteries.”

At 1:16 pm, a Battery Hamburg shell skidded across the top of the Texas’s conning tower, wrecking the bridge, killing the helmsman, and wounding 11 men. Texas’s genteel skipper, Captain Charles A. Baker, was thrown to the deck but not injured.

“Crash, shriek, and the sky has fallen, it seems. The enclosed bridge is suddenly dark, as glass, shrapnel and debris of all sorts fly around us. Clouds of yellow brown smoke obscure everything, and we simply do not know what has happened,” Somers wrote.

The executive officer in the conning tower promptly took control, keeping Texas in the game, hurling a shell at Hamburg that pierced her armor and knocked out one of the big guns. Another shell landed in the cabin of ship’s clerk, Warrant Officer M.A. Clark, but failed to explode. Somers went down to sick bay to check on the wounded. The seriously injured had “broken and torn legs and arms, causing great loss of blood. All were suffering from intense shock. Without transfusions they would not have had a chance to survive.”

The bombardment raged for another hour, until 3:01, when Admiral Deyo ordered his ships to pull out, for fear that their shells might hit advancing American troops. Collins was pleased with the result, writing later to Deyo, “I witnessed your Naval bombardment of the coastal batteries and covering strongpoints around Cherbourg … the results were excellent, and did much to engage the enemy’s fire while our troops stormed into Cherbourg from the rear.” They had tied down the German batteries and silenced some, buying time for the ground troops to close in and assault the positions.

Collins, watching from a hill outside the city, said, “It was a thrilling and … an awe-inspiring sight. I knew definitely then that Cherbourg was ours.”

White Flags From German Defenders

Meanwhile, VII Corps continued its advance. Under Major Gerden Johnson, the 1st Battalion, 12th Infantry, pushed hard north of Tourlaville against a coastal battery, which put out white flags. Johnson’s men moved forward with “Company B on the left disappearing down into a wooded draw. Suddenly Company B came under a barrage of mortar and 20mm anti-aircraft fire from the hill where the white flags were observed to still be waving. The barrage lasted for approximately 15 minutes.”

The barrage also took out the bulk of the battalion headquarters. Johnson rose from the mess and brought up some Sherman tanks, telling them to open fire on the defenders. The Shermans did so, and at 1:30 pm the garrison surrendered for real. The Americans showed restraint and took in 400 men and three massive 8-inch guns. The other two battalions entered Cherbourg itself that evening, hampered by scattered fire and mines. The 1st/12th fought all night to cut down pillboxes east of the Fort des Flamands. Early on the 26th, the Americans brought up tanks, and the 350 Germans in the pillboxes surrendered.

With that, the 4th Infantry’s part in the liberation of Cherbourg was done, but the fighting still raged. On the city’s west side, the 47th Infantry pushed through Cherbourg’s suburbs, heading for a fort at Equeurdreville. The fort stood atop a hill surrounded by a dry moat. But it was being used only as an artillery observation post and was not well defended.

On the morning of the 25th, a company of the 2nd/47th attacked the fort with mortar cover. In 15 minutes, the Germans were waving white flags. Simultaneously, the 3rd/47th attacked the Redoute des Forches with heavy artillery support. The German right collapsed, and the 9th Division streamed through, capturing more than 1,000 men.

Two Medals of Honor in Cherbourg

Von Schlieben had more bad news for his bosses: “Loss of the city shortly is unavoidable … 2,000 wounded without possibility of being moved. Is the destruction of the remaining troops necessary as part of the general picture in view of the failure of effective counterattacks? Directive urgently requested.”

On the afternoon of the 25th, Von Schlieben reported, “In addition to superiority in material and artillery, air force and tanks, heavy fire from the sea has started, directed by spotter planes. I must state in the line of duty that further sacrifices cannot alter anything.”

Rommel was stuck. All he could do was radio back, “You will continue to fight until the last cartridge in accordance with the order from the Führer.”

Meanwhile, the 79th Division continued its advance, aiming at Fort du Roule, the primary outer fort. The most formidable of Cherbourg’s defenses, Fort du Roule was built into the face of a rocky promontory above the city in best Vauban style. Its guns commanded the whole harbor and were in lower levels under the edge of a cliff. Above them were mortars, machine guns, and concrete pillboxes covering an antitank ditch.

To defeat this, the Americans sent in P-47s to bombard the position, but this had little impact. Next the Americans tried field artillery, with some effect. The 2nd and 3rd/314th attacked from the south but were pinned down by small-arms fire 700 yards from the fort. The Americans massed their .50-caliber machine guns and opened up on the defenders, shredding them and forcing the survivors to retreat. The 2nd Battalion then attacked through the 3rd Battalion’s cover, under heavy German machine-gun fire.

Now American valor shone. Corporal John D. Kelly’s platoon of E Company, 2nd/314th, was immobilized by German machine-gun fire from a pillbox. Kelly grabbed a 10-foot pole charge, crawled up the slope through enemy fire, and fixed the charge. It did not go off. He returned with another charge and this time blew off the ends of the German machine guns. Kelly returned up the slope a third time, blew open the pillbox’s rear door, and hurled hand grenades into it until the Germans emerged and surrendered.

At the same time, Company K of the 3rd/314th was also stopped by heavy German 88mm and machine-gun fire. Lieutenant Carlos C. Ogden, who had just taken over the company from its wounded commander, armed himself with rifle and grenades and advanced alone under fire toward the enemy emplacements. Despite a head wound, Ogden continued up the slope until from a place of vantage he fired a rifle grenade that destroyed the 88mm gun. With hand grenades he then knocked out the machine guns, receiving a second wound but enabling and inspiring his company to resume the advance. “I knew we were going to get killed if we stayed down there,” Ogden said later.

Both Kelly and Ogden were awarded the Medal of Honor. Kelly died of wounds in a subsequent action, on November 23, 1944, and lies buried in the U.S. Military Cemetery in Epinal, France. Ogden reached the rank of major before retiring from the Army, died in 2001, and is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

The Surrender of General Von Schlieben

Bravery of this nature further crumbled the German defenses, and white flags and surrenders started popping up in Fort du Roule. By midnight, the 314th controlled the fort’s upper defenses.

The 313th attacked from Hameau Gringor into the flats southeast of Cherbourg but could not get much farther, as they came under fire from the lower-level Fort du Roule guns, still not captured. To put the fort out of business, the Americans lowered demolitions from the captured top area, and used point-blank fire from antitank guns. Staff Sergeant Paul A. Hurst led a demolition team around the cliff’s west side, which finally overwhelmed the fort’s stubborn defenders.

The 47th Infantry had a hard time with a fixed defense, too, battling the old arsenal, which was studded with antitank, antiaircraft, and machine guns. Bad weather and heavy smoke from German demolition teams prevented the use of artillery. General Eddy, commanding the 9th, delayed his assault until the 27th.

It turned out to be a wise move. On the 26th, the 39th Infantry learned from a POW that von Schlieben was dug in at an underground shelter at St. Sauveur on Cherbourg’s southern outskirts. Von Schlieben had fled his tactical headquarters because of American shelling. At 3:06 pm, he fired off a last message to Berlin: “Documents burned, codes destroyed.”

Two companies of the 39th hustled over to take the general, hoping that he would then surrender the fortress. The Americans dashed through artillery and rocket fire to the tunnel entrance and sent in a POW to ask for von Schlieben’s surrender. The demand was refused. The Americans brought up two tank destroyers to fire into the bunker, and Eddy wrote later in his diary, “The tank destroyers’ projectiles had caused so much dust and fumes … that the German soldiers, once finding that the white flag had been raised, began to pour out. These Germans were in such a rush that they denied the General his wish for a more formal surrender. The avalanche of soldiers carried him and his party with it.” Out came von Schlieben, the top naval commander in Cherbourg, Rear Admiral Walther Hennecke, and 800 prisoners.

Von Schlieben accepted lunch from Eddy but would not order a general surrender for the fortress. He could not; his communications had broken down. Just to add to his misery, Von Schlieben’s next meals consisted of K-rations, and there was no shower in the farmhouse where he was held, and the vehicle carrying his trunk from Cherbourg collided with a truck en route to the U.S. First Army’s command post. The general’s uniforms were strewn across the road and souvenir-hunting GIs got most of the gold braid and rank badges before MPs could pick them up.

20,000 More POWs

The 39th kept moving and bagged another surrender, 400 Germans dug in at Cherbourg City Hall. They surrendered when told that von Schlieben had gone in the bag. The Americans also promised protection from French snipers. Along with them was a mass of ragged male and female slave laborers who had built and maintained the fortress.

Lieutenant Byron Nelson, the 79th’s forward observer, entered the town and walked into a tavern called Emil Ludwig’s, right on the beach, alongside his division’s top brass. They found a picture of Hitler hanging on the wall. A colonel took it down and ground his heel “right in Der Führer’s face.” Nelson knew who had won this battle, he said later, “The lowly infantryman.”

Von Schlieben’s surrender had a domino impact on the remaining German positions. Next day, Eddy planned a three-battalion assault on the arsenal, but sent in a psychological warfare unit first to ask Maj. Gen. Robert Sattler, Cherbourg’s deputy commander, who headed the arsenal’s defense, for surrender. Told that von Schlieben had given up, Sattler ran up white flags, and the 47th Infantry took 400 more POWs without a fight.

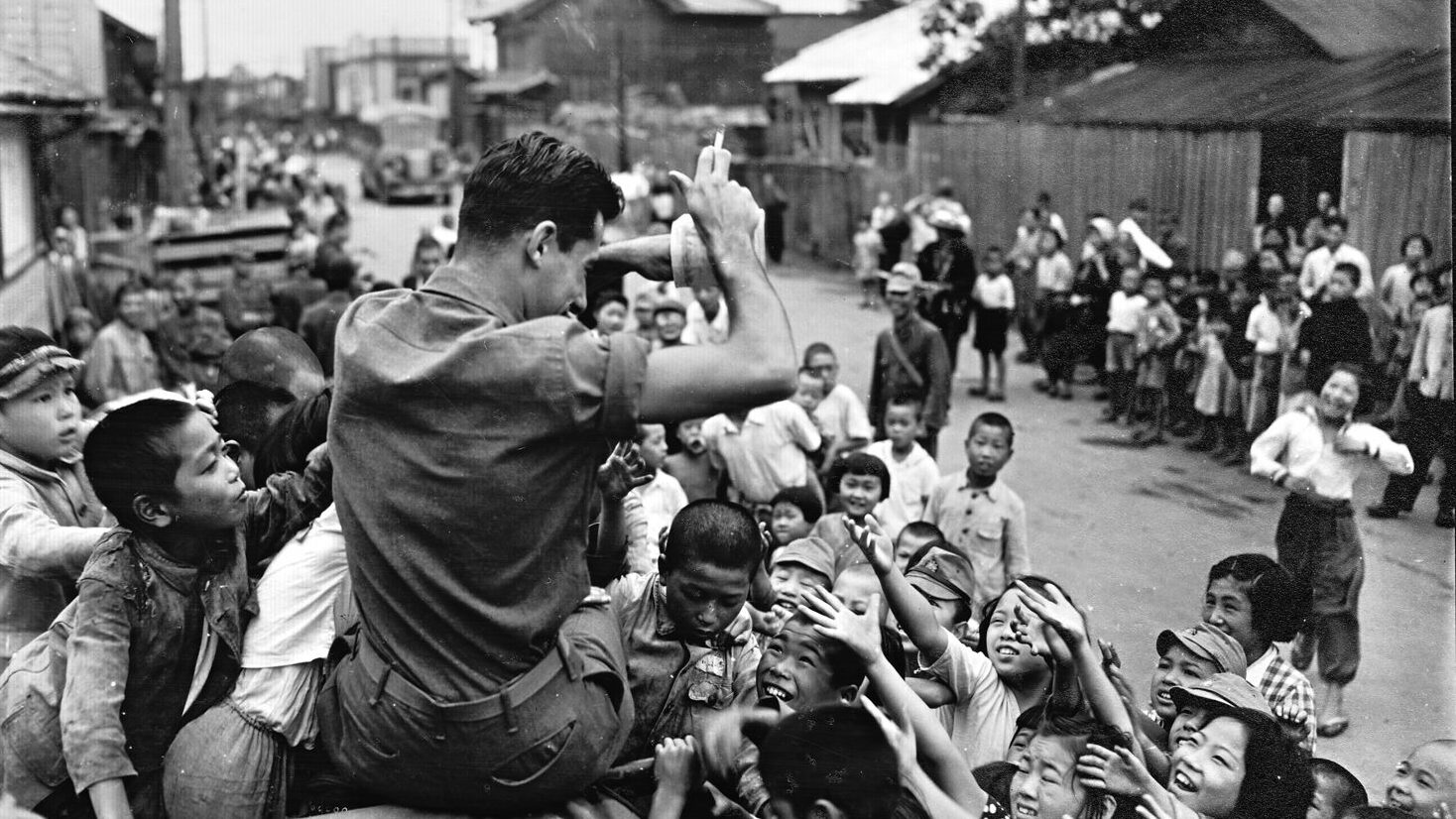

Some 20,000 German prisoners tossed down their coal scuttle helmets, flipped on their peaked caps, and shuffled into captivity four abreast. Sergeant Hank Henderson, a 4th Infantry medic, watched them go by. “One little German corporal stepped out of ranks and said, ‘I would like to see that automatic artillery in action before you shoot me.’ He thought it was automatic because our batteries fired so rapidly,” Henderson said. Nearly speechless, Henderson told the corporal the artillery was not automatic and nobody was going to be shot.

“Best-Planned Demolition in History”

But 6,000 Germans still fought on in Cap de la Hague west and east of the city. To the east, the 22nd Infantry moved against the well-defended Maupertus airfield, attacking at 11 am on the 26th with all three battalions. It took the Americans all day to take the airfield.

After that, the 22nd turned to attack Battery Hamburg, which had stood off the Navy effectively. With fire from the 44th Field Artillery Battalion, the battery was soon silenced, and 990 Germans surrendered, filling the already swollen POW camps. With that, German defenses in the west Cotentin collapsed and armored cavalry found the area unoccupied.

Cap de la Hague was a tougher nut, with an estimated 3,000 troops defending it. On June 28, the 9th Division went in to sweep the area, while the 79th headed south to rejoin VIII Corps and the planned breakout.

The Americans attacked on the morning of the 29th, with the 47th Infantry on the north coast and the 60th in the center, on the main cape highway. Little resistance was found until the troops reached Beaumont-Hague, with GIs clambering through fortified but unoccupied positions to seize a ridge at Nicolle. From there, they assaulted a main German position with artillery support and bagged 250 prisoners.

The Germans were still fighting back, though, relying on antitank ditches and guns to stop the Americans in the open terrain. The 3rd/60th blasted through the Germans with tank destroyer and tank support and overran the key road junction on June 30. By the end of the day, the mop-up was complete, with about 6,000 POWs going in the bag, twice the number expected. The Cotentin Peninsula was liberated. Cherbourg was free. And the port was a wreck.

“The demolition of the port is a masterful job, beyond a doubt the most complete, intensive, and best-planned demolition in history,” wrote Colonel Alvin G. Viney, who prepared the original engineer plan for port rehabilitation. With nearly a month to blast open the port, von Schlieben’s demolition teams had done their work well, starting as early as June 7, the day after D-Day.

All basins in the harbor were blocked with sunken ships. The harbor was strewn with mines. Gare Maritime, which controlled the electricity and heating plant for the port, had been demolished. Some 20,000 cubic yards of masonry were blasted into the large, deep basin used in peacetime for liners like the Queen Mary. The entrance to this basin was blocked by two large ships. Quay walls were damaged. Cranes were demolished. The ocean poured through a cratered breakwater. “The whole port was as nearly a wreck as demolitions could make of it,” said the U.S. official history. Hennecke got an Iron Cross from Hitler for his efficiency.

The only good news for the Americans was that the city itself and its rail lines were in decent shape, so the Americans could move supplies and equipment into Cherbourg to clear the harbor speedily. And the city had fallen much earlier than expected, so the Americans had time to start unclogging the port.

Tallying the Losses on Both Sides

They also had time to count the cost. In the battle for the Cotentin and Cherbourg, VII Corps had lost 2,800 killed, 5,700 missing, and 13,500 wounded. German casualties were more difficult to count, but some 39,000 men had been taken prisoner. These would be shipped to American and Canadian POW camps across the Atlantic.

There the defeated men of Cherbourg met up with more determined German POWs, Afrika Korps veterans, and U-boat crews who were still full of Nazi elitism. They did not believe the Allies were winning the war. When the bedraggled Cherbourg POWs began pouring into camps in Louisiana, Arkansas, and Manitoba, they set their longer-held brethren straight—the Allies were stomping Germany thoroughly. It was a shock for men who had also fought with Rommel, albeit in happier times in North Africa.

Von Schlieben wound up in British hands, at the senior officers’ camp at Trent Park, where he and other generals whined to each other about their failures, as British wire recorders picked up every conversation for intelligence purposes. “With his pink complexion, round boyish face, huge bulk and lumbering gait he gives the appearance of an overgrown, mentally under-developed school-boy type who will bully his inferiors and toady to his superiors. At first very truculent. Polite firmness proved successful. Has more bluff than guts. Like most prisoners of war he is much inclined to self-pity. Conversation with him revealed colossal ignorance. He said the Russians were a primitive people who had achieved little. Scotland was a completely unknown place to him. He asked if it were hilly or flat,” the British assessment of von Schlieben wrote. He was freed in 1947 and died in Giessen in then West Germany in 1964.

Also devastated was Col. Gen. Friedrich Dollmann, who commanded the Seventh Army. Cherbourg fell under his command, and two days after the surrender Dollmann was found dead in his headquarters’ bathroom near Le Mans. Officially, he died of a heart attack. But his senior officers believed he committed suicide out of shame over the loss of Cherbourg.

Also upset was Hitler. Despite the “field of ruins,” Cherbourg had not held out as long as expected, and von Schlieben’s quick capitulation marked him down as a poor specimen of Nazi leadership.

Collins did better. Ahead for him was promotion to full general in 1948 and appointment as U.S. Army Chief of Staff in 1949. He served as U.S. representative on the NATO Standing Group after that, retired in 1956, and served as a consultant with Pfizer & Co. until April 1969. He died in 1987.

“Everybody Take 24 Hours and Get Drunk”

Now came the difficult task of cleaning up Cherbourg harbor, a Navy task, under Rear Admiral John Wilkes, who arrived on July 14, along with a few hundred Navy Seabees. They went to work, backed by six British and three American salvage vessels and scores of minesweepers, all veterans of port-clearing operations in North Africa, Palermo, and Naples. Some 133 mines were swept by July 13, but not all. By August 12, three American and one British craft were sunk.

The first freight was landed at Cherbourg on July 16, when Navy DUKWs began discharging cargoes from four Liberty ships on a specially cleared beach. But the main basins were not cleared until September 21, a three-month delay, which meant that the invasion beaches still had to be used to unload supplies. von Schlieben had done his work well. The log jam of supplies would mean that the Anglo-American advance, short of fuel, would sputter to a halt near the German frontier.

But on June 30, as engineers from the 101st Airborne Division rolled into town to help reduce strongpoints, these issues were all in the future. The engineers found massive damage to the city, but much of it intact. GIs puzzled over that French social artifact, the sidewalk urinal, and queued up to use the old Wehrmacht brothels, thoughtfully left intact and in business. Troops were warned about contracting venereal disease.

Instead, they culled souvenirs, of which there were plenty. The best one was a massive underground wine cellar liberated by the 9th Infantry Division. At first, General Eddy tried to keep his men from drinking it; then he realized how impossible that was. Besides, his men had just fought a harsh and horrific battle.

“Okay,” he finally said. “Everybody take 24 hours and get drunk.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments