By Glenn Barnett

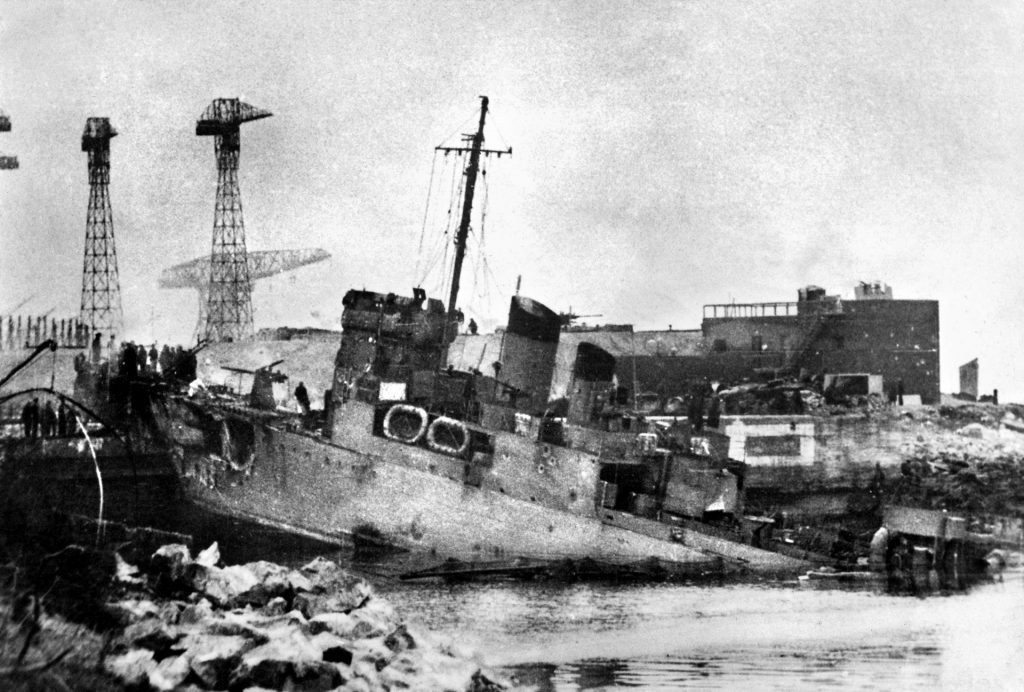

At high tide on the night of March 28, 1942, an American-built British destroyer disguised as a German torpedo boat steamed boldly up the estuary of the Loire River in occupied France. Her target was the Normandie dry dock near the town of St. Nazaire.

Built for the French ocean liner Normandie, the dock was the only facility on the German-occupied Atlantic coast large enough to accommodate the Kriegsmarine battleship Tirpitz, sister of fabled Bismarck.

Tirpitz had only recently left her German base and sheltered in a Norwegian fiord. There was a very real fear at the British Admiralty that she would soon commerce raiding in the North Atlantic using St. Nazire as a base.

The British designed Operation Chariot to neutralize the French docking facilities, and for the rest of their lives the survivors of the raid would be known as “charioteers.”

The American built “four piper” HMS Campbeltown was chosen to lead the raid to destroy the dock at St. Nazaire. She was stripped of three of her smoke stacks in order to resemble a German torpedo boat. Her innards were gutted to reduce weight, and her bow was packed with a nasty surprise. Three tons of high explosives, hidden beneath false bulkheads, were time-delayed to explode some six hours after her crew of commandos had abandoned her.

Flying the German naval ensign, Campbeltown and a flotilla of gunboats fooled the German shore batteries long enough to make a final run for St. Nazaire. Then all hell broke loose. The defensive batteries opened up, and under heavy and close-range fire the destroyer rammed the gates of the target dry dock and wedged fast. British commandos scuttled the ship on the spot. They evacuated their wounded under fire and went ashore to join other commandos who were engaged in destroying the dock’s pumping house.

Five Victoria Crosses would be awarded for this night’s work.

The next morning, when the British invaders had been repulsed, a German boarding party, surveying the damage, went aboard Campbeltown to determine how best to move her away from the damaged dock. At 11:20 in the morning, the time-delayed explosives blew up, destroying Campbeltown, killing over 350 Germans, and completely wrecking the dock’s gate. The Germans would never attempt to repair it, and Tirpitz would spend the rest of her short life in Norway.

The raid at St. Nazaire highlighted the importance of the “Bases for Destroyers” deal worked out between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the new British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the summer of 1940. In exchange for long-term leases on British Commonwealth islands in the Caribbean, the United States turned over 50 World War I vintage destroyers, which the British desperately needed to replace their growing losses and to provide protection for the all-important North Atlantic convoys.

This limited exchange became the blueprint of the Lend-Lease program, which enabled the Arsenal of Democracy to share her wealth of production, both agricultural and manufactured, with her hard-pressed allies.

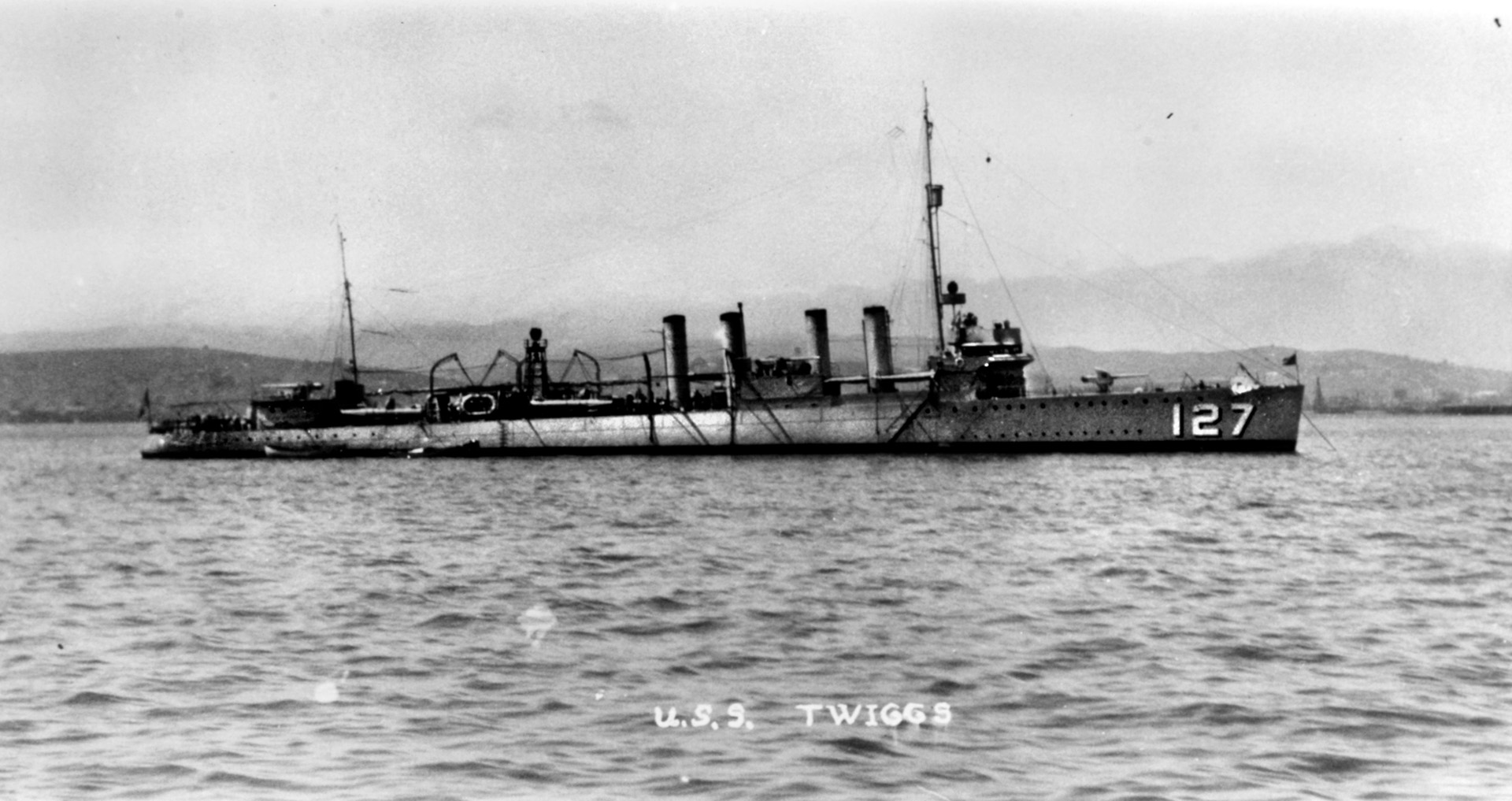

HMS Campbeltown had been built too late to fight in the last war. Launched in 1919 at the Bath Iron Works in Maine, she was commissioned as the USS Buchanan after Franklin Buchanan, the first superintendent of the United States Naval Academy. She had a flush deck, sloping toward her stern, and the distinctive four smoke stacks common to American destroyers at the time.

In the years following the war, there was not much for America’s fleet of new destroyers to do. Some were sent to the Balkans to help with food distribution and refugee evacuation. Others were strung out between Newfoundland and the Azores in May 1919 to serve as beacons for the first transatlantic flight of U.S. Navy seaplanes.

As a result of the Washington Naval Treaty of 1921, Buchanan and dozens of other “four pipers” were taken out of commission the next year and given a rust-resistant paint job. Moored side by side in naval backwaters at San Diego and Philadelphia, the collection of over 120 destroyers became known as “Red Lead Row.” Most of them would spend the next 17 years in suspension.

Red Lead Row would be called back to service abruptly in December 1939 in response to the beginning of hostilities in Europe. Naval planners were aware that the bulk of America’s destroyer fleet was woefully outdated. Designers worked overtime to create the new Fletcher-class destroyers to replace them. But for the first years of the war, the “four pipers” would have to make do. They all needed to be modernized and refitted. Many were in such bad shape that they were just scraped.

Immediately after rejoining the service, they were sent to patrol the vast American coastline as well as the Caribbean and Central American waters as part of a “Neutrality Patrol.” The patrol’s primary mission was to protect the approaches to the Panama Canal. While the old destroyers were being brought out of retirement, the world stage was not dormant. Germany launched her blitzkrieg against the West that spring, overrunning France and the Low Countries. At sea, the Royal Navy had its hands full with the German Kriegsmarine.

Once Germany occupied Norway and France, the Royal Navy’s problems were greatly compounded. U-boats and air attacks took a fierce toll on merchant ships and the destroyers that guarded them. By July 1940, the British had lost 28 destroyers to all causes, as well as a battleship, two aircraft carriers, and three cruisers. These losses were unsustainable.

Churchill appealed personally to President Roosevelt for help.

The American president was uniquely qualified to understand the problems the British faced. He had been Assistant Secretary of the Navy from 1913-1920, at a time when Churchill was Lord of the Admiralty. It was on his watch that the “four pipers” were designed and built.

On September 3, 1940, the White House announced that the president had signed an executive order turning over the 50 destroyers to the British in exchange for leases of land in Antigua, British Guiana, Jamaica, St. Lucia, Bermuda, Trinidad, and Newfoundland. The leases were for 99 years and envisioned the construction and utilization of military bases.

So many of the four-stacker destroyers had been built and stored that the United States Navy was still able to retain 80 of them for its own use.

The 50 chosen destroyers steamed for Halifax, Nova Scotia, where their crews would train their new owners. American style equipment was removed and replaced with British gear. All of the ships were stricken from the U.S. Navy list and assigned new names.

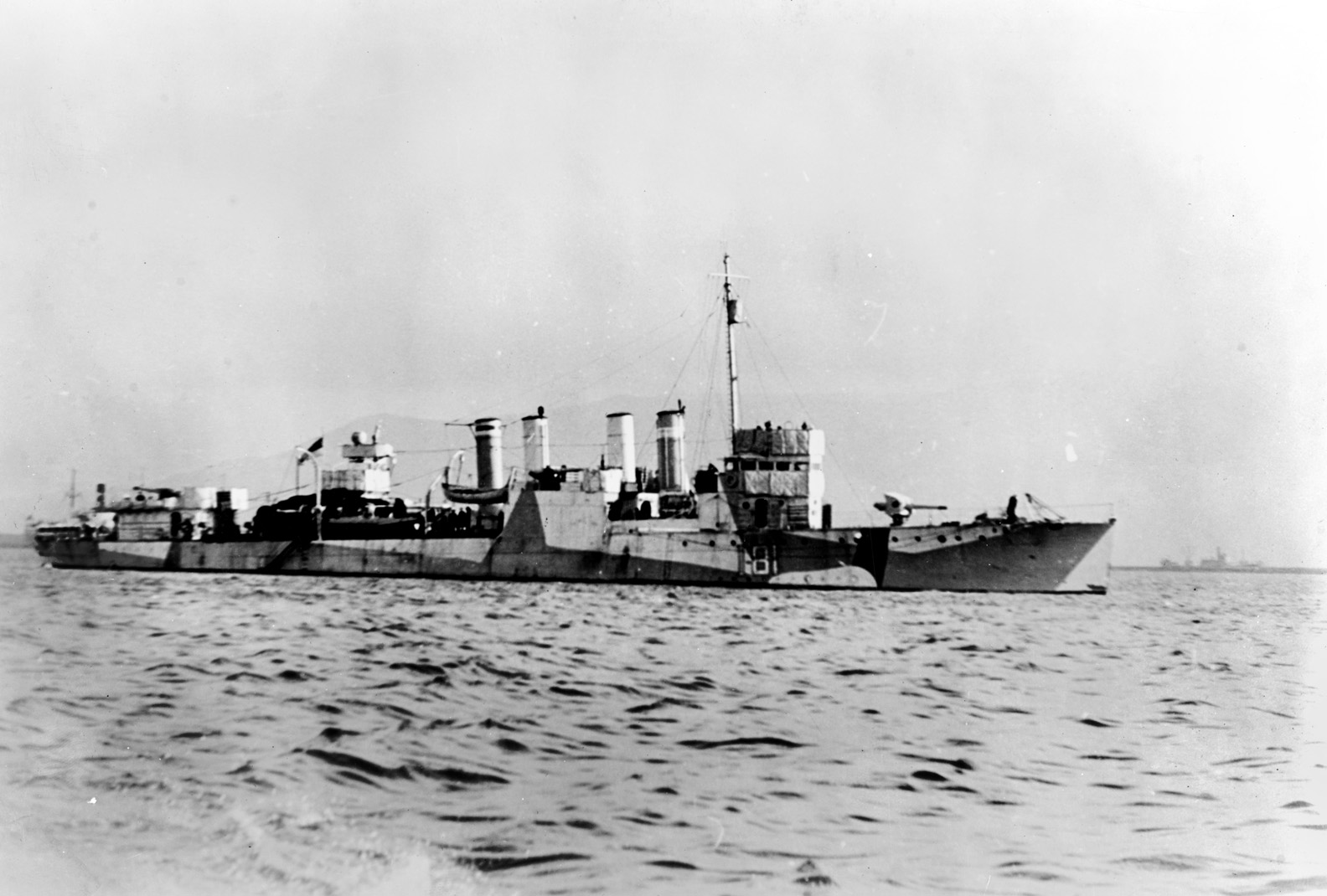

The 50 new acquisitions were given names of towns in the British Isles that had similarly named towns in the United States. It was an effort to stress the common heritage and cause of the two countries. Collectively these old boats became known as the Town-class destroyers.

Only now did the British sailors begin to learn of the shortcomings of their new charges. The Town-class boats had a large turning circle, which made them difficult to steer, and there would be several accidents because of it. Their narrow sterns exposed their propellers to damage when docking. They also rode high in the water when their fuel was consumed. This made them pop like corks in high seas.

The American solution was to flood the fuel bunkers with seawater to maintain balance and an even keel. Before refueling, the oil-fouled seawater was pumped out, a practice that would shock modern day conservationists. The British were loath, however, to do anything that might threaten to contaminate their fuel oil.

The Town-class destroyers were also small. Weighing in between 1,000 and 1,200 tons, they were half the size of destroyers coming off the ways in 1940. Their standard complement was between 110 and 120 men. Their firepower was also diminutive. Each boat was fitted with four 4-inch guns. The only enemies that could be intimidated with these were U-boats and E-boats (the German version of the PT boat). Fortunately, that was all these destroyers ever had to face. Because of their odd size, the Royal Navy would think of them all as frigates.

The Campbeltown was one of the worst in terms of structural stability. Her bow needed replacing, she needed new propellers, and her electronics malfunctioned. Even after an overhaul in October 1941, she was in such poor condition that she was selected for the suicide mission against St. Nazaire.

Almost immediately upon delivery to the Royal Navy, the Towns became an international force. Eight of them were turned over straight away to the Canadians for escort and anti-submarine duties in their home waters. Another nine would go to the Soviet Navy for protection of convoys in the North Sea. The Royal Norwegian Navy in exile would man five of them, while other crews would be composed of Dutch and Free French sailors. Some of these well-used ships would serve in the navies of four different nations.

For the most part, the Towns were used for convoy duty in the North Atlantic. They would be stationed in Canada, Iceland, and in Britain as part of the Western Approaches command. Some of them provided escort for Operation Torch and the invasion of North Africa, pushing into the Mediterranean. Their other primary function would be as minelayers.

In battles with the U-boats, the Towns actually came off second best. They are credited with sinking four U-boats while losing seven of their own to German torpedoes. These losses include the Russian boat Dyatelni (formerly HMS Churchill), which was torpedoed in the White Sea in January 1945 while protecting a Baltic convoy.

Several U-boats felt the sting of the Towns’ depth charges. The “four pipers” must be credited with foiling countless attacks against Allied merchant shipping by keeping the U-boats at bay.

HMS Broadway (USS Hunt) participated in the capture of U-110 and its priceless cache of German naval codebooks. Hundreds of Allied seaman owed their lives to the “four pipers” when, their own ships sunk, they were plucked from the frigid waters of the North Atlantic by the Towns.

One of the most successful of the destroyers in the anti-submarine role was HMS Stanley (USS McCalla). On December 17, 1941, while on convoy duty in the Mediterranean, Stanley and four other destroyers responded to the report of a U-boat sighting from the air. They managed to find and sink U-131 while rescuing 55 German submariners.

The next day, Stanley and HMS Blankney sank U-434. Then her luck ran out. The following day Stanley’s lookouts spotted U-574 and gave chase. In the desperate fight, she was struck by a torpedo and blew up. Only 25 of her crew survived.

In September 1943, St. Croix was hit by three torpedoes and sunk. Hard action made it impossible to pick up her survivors until the next day. The crew of HMS Itchen pulled 81 of St. Croix’ crew from the water. The following day, the Itchen was torpedoed and sunk. There were only two survivors of Itchen and one from St. Croix.

As the war progressed, newer and more capable destroyers became available in quantity, and the Towns were gradually replaced. Only in the Soviet navy did they remain on frontline duty until the Nazi surrender. After the war, all of them were scrapped. In a bizarre gesture of friendship, the Soviet navy actually returned their surviving four pipers to the Royal Navy in 1949. These were immediately broken up.

The last Town-class destroyer to be retired from active duty was HMS Leamington (USS Twiggs), another return from the Soviet navy. She still steamed under her own power until December 1951.

The desperate days of the early war called for desperate measures. The Towns were no match for modern destroyers, but they packed enough punch to help convoys get through at a time when every ton of supplies was vital to a flagging war effort in Britain.

The over-aged destroyers were a stopgap measure to be sure. Yet they were the right thing at the right time for the right reason.

Author Glenn Barnett is a retired college instructor and aerospace engineer. He worked on the Apache helicopter, B-1B bomber, and Space Shuttle. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History.