By William G. Dennis

Géneral d’ Armée Jacques-Philippe Leclerc’s service to France during World War II made him one of the few heroes to be admired by the whole country. France was divided between those who refused to give in to Germany, those who obeyed the collaborationist government at Vichy, and the communists who opposed both.

Leclerc graduated from Saint-Cyr Military Academy with remarkably high marks, and graduated first in his class from the Cavalry School at Saumur. He was first posted to France’s colonial cavalry, the 8th Regiment of Spahis in Morocco, and later served with a Goum unit in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco.

His service to the Allied cause that made him a hero began when he escaped from German captivity in 1940. At that time, most of France was occupied by Germany and the rest was governed by an unsavory collaborationist regime from its capital at Vichy. It rounded up Jews at the behest of the Nazis and even sent Frenchmen to work as slaves in German factories.

Under Marshal Petain,Vichy still ruled France’s colonial empire, including much of North Africa. The rest of North Africa was divided between Britain, Italy, and Spain. Italy and France were latecomers who had seized their colonies in the latter half of the 19th century and the early twentieth. Their colonies were restive and required armies made up of European troops and native units to keep them under control. Skirmishes with rebels were endemic and some major campaigns took place.

Leclerc was born Philippe Hauteclocque. After his escape from France, he sought to divert the Vichy government’s attention from his family so he took his nom de guerre, arriving in England on July 25, 1940, to join Charles De Gaulle who, with British help, was working to bring France’s African colonies over to the Allied side.

It was an opportune time for the move. As France was falling, Italy declared war on the Allies and attacked British-controlled Egypt. On June 14, 1940, British, colonial, and commonwealth troops had defeated the Italians and crushed their forces in North Africa with Operation Compass.

Leclerc was well equipped for that task. Decorated for valor during his years of service in North Africa, he was fluent in Arabic, proficient in Berber, and well grounded in conducting long-range desert operations on a logistical shoestring budget.

Leclerc based himself in Chad, where he began assembling existing forces and recruiting new troops. He had little equipment—and most of that was obsolete. Still, Allied strength was slowly growing. The British were supplying obsolescent Blenheim bombers and Bedford trucks that were better suited to desert warfare than anything the French had.

A patrol of the British Long-Range Desert Group came in from Egypt looking for bases from which to strike Italian positions in western and southern Libya—strikes designed to divert Italian troops from the fighting along the Mediterranean coast.

The first action mounted from Chad was an Anglo/French raid on the Italian outpost at Murzuk, the most important town in the Libyan desert. The garrison held an Ottoman-era fortress and positions at the local airfield. While one group put suppressive fire onto the fortress, another attacked the airfield, destroying airplanes and a fuel dump. The raiders succeeded in spite of scant training and little support.

Encouraged, Leclerc struck at Italian communications with East Africa by raiding Kufra—an important way point for air travel to Italian possessions further east. Leclerc started by testing Italian defenses with a reconnaissance‐in‐force.

Initially, there were air attacks and scouting by camel-mounted troops, followed by ground action. Leclerc assembled an attack echelon of 100 Europeans and 300 Africans mounted in 55 trucks and supported by two armored cars and a pair of 75mm mountain guns. A second echelon of 100 trucks and 150 men handled supply and logistics.

The Italians were alert, but the advance group of this force reached the village of El Giof on the outskirts of the town without detection. Leclerc slipped into the headman’s house and learned that the Italians pulled their outposts into the fort and buttoned up during the night. An attack on the unguarded airfield destroyed two aircraft. The attackers melted into the desert, where camouflage and dispersal kept Italian bombers from finding them the next day.

Meanwhile, the British were advancing into Libya and the way was open for Leclerc to move north. The plan was to capture Kufra and link up with the advancing British. Leclerc’s forces moved out on February 17, 1941. The first objective was to defeat the Italian Sahariania (locally raised troops) guarding the town. Acheiving that, the focus of the battle shifted to the mud-walled fort; 75mm shells punched through the walls before they exploded and 81mm mortar shells dropped inside them. The Italians surrendered on March 1.

This was Free France’s first real victory and Leclerc led his men in swearing not to put down their weapons until the tricolor flew over the cathedral of Strasbourg in Alsace. The provinces of Alsace and Lorraine had been lost to France in the Franco-Prussian war, regained at the end of WWI, and lost again in 1940.

General Erwin Rommel arrived in Libya in February 1941 at the head of a mechanized force—the Afrika Korps. Together, the German and Italians in northern Libya threw back the British. With German troops now in Libya, Leclerc’s troops were no longer strong enough to move any further. His supply line from the West African ports stretched a thousand miles and gasoline was so scarce that it was carried to forward bases by camels.

But the situation began to improve when Germany invaded the Soviet Union, allowing the British to reinforce their garrison in Egypt. A trickle of new equipment and supplies for Leclerc’s forces began to arrive. The equipment was welcome, but British rations must have been depressing to the gastronomes among the French. At that time, the Eighth Army in North Africa was being fed mostly bully beef, choke-dog biscuits, peas porridge, and oatmeal—over and over again.

For the next nine months, the battle moved to and fro across North Africa’s Mediterranean coast. Leclerc no longer faced only poorly armed and badly led Italians, so capturing and holding Italian positions closer to the coast was not a good option. But raids against Italian positions in southwestern Libya, the Fezzan, were feasible. In Operation Fezzan I, Leclerc deployed a force of 500 men divided into several parties.

The raids began on February 15, 1942, and lasted for 15 days. They cost the French eight killed and 15 wounded but destroyed four Italian forts, captured 50 Italians, and destroyed aircraft and supply dumps. A U.S. liaison officer with Leclerc described him as “a remarkable soldier, young, energetic, and absolutely adored by his officers and men.”

Leclerc and his command waited out the summer of 1942 as both sides built up their strength and the Italians reoccupied the Fezzan. The Eighth Army had a decisive victory at El Alamein in October; in November Anglo/American armies landed in North Africa (Operation Torch). With the German and Italian armies locked in battle with the main Allied armies, Leclerc’s small force could move against Italy’s vulnerable southern flank.

For Fezzan II, his force numbered 3,500 men, including a strong, if diverse, artillery component. Leclerc’s men moved in mid-December 1942 and, by mid-January 1943, had eliminated the Italian positions in the Fezzan, reached Tripoli, and linked up with Bernard Montgomery’s British Eighth Army—a 2,000-mile journey.

Monty recognized the man in the dusty, worn-out French uniform as a capable and seasoned desert campaigner. The British supplied Leclerc’s troops with British uniforms and gear, traded British weapons for most of their Italian arms, and replaced their worn-out vehicles. It was still a lightly-armed force best suited to fighting in rough terrain.

The British designated Leclerc and his troops as “Force L.” The 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion, made up mostly of anti-fascist Spaniards, had served with the Eighth Army. It joined Leclerc’s command, as did a small Greek force. British engineers and an anti-aircraft unit were also attached.

The British faced an Italian/German force along the Tunisia-Libya border. Montgomery posted Force L to the desert flank of the battle line and tasked it with holding mountain passes against an attempt to flank the Eighth Army. The German Fifth Panzer Army commander, Hans-Jürgen von Arnim, aimed the last major Axis offensive against the Eighth Army at Force L. When he learned the strength of the attack, Montgomery attempted to get Leclerc to retreat, but the Frenchman had confidence in his plan. When the battle ended, the Axis forces retreated with heavy losses.

The U.S. committed to equipping three French armored divisions and four infantry divisions to be organized on the American model. The armored divisions had three major subordinate commands that the Americans called “combat commands”—similar to infantry regiments—that also controlled the maneuver and artillery battalions.

The tank battalions were primarily equipped with M-4 Shermans, with one company per battalion equipped with Stuart M-3A3 light tanks. Its three infantry battalions were mounted in reliable American halftracks. Leclerc’s anti-tank unit was equipped with M10 tank destroyers (TDs)—lightly armored tracked vehicles mounting a high-velocity cannon in an open-topped turret. Its three battalions of artillery were equipped with 105mm howitzers mounted on M7 carriers (modified Sherman tanks). Belton Cooper, author of Death Traps, considered them to be one of the best pieces of U.S. equipment in WWII.

There were several departures from the American table of organization. Each firing battery had nine guns instead of six, as in an American armored division. This gave it 81 guns instead of 54; each gun team had a halftrack with trailer a to carry ammunition. Another departure was to strip down six-by-six trucks and mount a 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft gun on the bed instead of towing it. Leclerc also organized two subordinate headquarters within each combat command so that each could be smoothly split into subgroups.

In a May 13, 1944, ceremony in Algeria, Force L became the 2e Division Blindée—the 2nd French Armored Division. The division is still in active service and its infantry component is officially known as “The Regiment that Marched from Chad.”

Turning Force L into a full armored division involved much recruiting and reorganization. The black Africans were transferred to units that would garrison France’s new protectorate in southern Libya. There had been a steady trickle of “evades”—young men that had slipped out of France and ended up in Africa. Most were assigned to a temporary holding unit along with anti-fascist Spaniards and Italians. It was not enough, so some regiments from the French army in Algeria were transferred to the 2nd Armored. Moroccan horse cavalry also was assigned and motorized with T-17 “Staghorns” and M-8 “Greyhound” armored cars.

The division included a medical battalion organized and equipped like an American unit, but its personnel were a definite departure. There were two detachments of female ambulance drivers commonly referred to as the “Rochambelles” and the “Marinettes.” The ambulance drivers also included a unit of British Quakers that Leclerc persuaded the Eighth Army to transfer to him.

The oddest part of the division was its anti-tank regiment. The British Royal Navy had fought a series of successful actions to keep French ships out of Axis hands. The regiment was formed mostly of men who had been captured in these actions and frequently spent months in prison camps alongside captured U-boat crews. Eventually, it became clear to many of them that, whatever their hatred of the Royal Navy that had so often humiliated them, the real enemy was Germany. A thousand of them volunteered to become French naval infantry. Being mostly technicians and gunners, it was not their first choice. But being aboard TDs—ships of the land, so to speak—fit them well. The regiment was augmented with crewmen off of French ships sunk or disabled during the invasion of North Africa. They became the Régiment Blindée des Fusilier Marins.”

There were few officers in any army that could have quickly pulled such a disparate group into the fine fighting force that the 2nd became. With such a diverse group and little time for training Leclerc’s history and personality played a big part in building his division into an effective force.

Eventually, enough men were found, most of the equipment arrived, and the troops were trained to use it. Once the division passed the American Rearmament Commission’s training and tests, on the equipment that was available, it was on to England to get ready for the Normandy invasion.

The division began arriving in Yorkshire in late April and most of it was there for the next two months. It was a time for a last stint of intense training. Most of the tanks had arrived late, and simulators were a poor substitute.

It was becoming clear that the newer panzer models outclassed the M-4, and that the only answer to that was to make good use of what the division had and support them with artillery and air. That meant training to take advantage of terrain, using the Sherman’s speed and maneuverability to its maximum—and shooting well. By June 12, the division’s tankers had passed the training.

On July 29, eight weeks after D-Day, the division landed in Normandy. The people of the devastated countryside were delighted to see French troops and recruits began to stream in. Among the first was Leclerc’s nephew.

The 2nd French Armored was part of the spearheads Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army sent attacking north and easterly behind the German lines and moving much faster than the German troops could. It had become a war of movement and cavalrymen like Patton and Leclerc were loving it. The Allied goal was to link up Third Army with the British and Canadian armies thrusting down from the north near Alençon and catch what remained of the German forces in Normandy in the Falaise Pocket.

Leclerc’s division was part of Major General Lee Haislip’s XV Corps, which was moving to seal the pocket. The country was still the frustrating Norman bocage, with its hedge-lined sunken roads around small fields interspersed with forests. It was good defensive territory but at least the Germans now had little time or inclination to dig in and, at close quarters, the nimble American armor could acquit itself well against the heavier panzers.

Leclerc’s people were encountering scattered forces and roadblocks. The plan was for armored spear points to roll over the German forces. If that did not work, flank them and leave them for the artillery and following infantry. Leclerc seemed to be everywhere in the front-lines, demanding action and urging subordinate commanders on.

His being so close to the front horrified his subordinate commanders. When he drove up to the command post of one of his leading battalions, its commander, Lt. Col. Rouvillois, called out that he was in full view of German tanks. “You have no right to take such risks. If you are killed, who will command the division?” “Rouvillois will,” Leclerc told the startled battalion commander. “You do your job and I will do mine.”

But being so far forward paid off in an unexpected way. Driving from Mamers toward Alençon late at night, he met a kubelwagen coming toward him. Leclerc and his aide opened fire, killing two Germans and capturing one. The men were carrying orders for what was left of the 9th Panzer Division to move to Alençon.

This confirmed that the front lines had ruptured and that the town did not have well-organized defenses. The faster his troops got there, the more easily Alençon would fall. An audacious thrust on Alençon the night of August 11 paid off early the next morning when his troops captured the city with the bridges over the Sarthe River intact. It also enabled Leclerc to block the roads the Germans were intending to use. Prevented from occupying Alençon, 9th Panzer took up positions north of it in the Écouves Forest.

A warning from a resistance fighter that the forest contained strong German forces led to Leclerc’s most controversial move. Haislip’s orders were for Leclerc to bypass the forest on the west while the American 5th Armored bypassed it on the east. Instead, Leclerc sent only one combat command west of the forest, one through the western fringe of the forest and one east of it into the operational area of the 5th Armored.

A combat command of the 5th had already cleared the town of Sées and was waiting for a gasoline resupply. Leclerc’s troops caused a traffic jam in the town that delayed the fuel trucks.

The 5th’s combat command had been tasked with capturing Argentan. By the time the attack took place, the Germans had strengthened the defenses of that town and the attack made little progress. Had it succeeded, many more Germans who escaped the Falaise Pocket might have been captured.

The TDs with the column that passed west of the forest had the incredible luck to come upon a column of tanks and trucks from the 9th Panzer. The crews were resting on the grass nearby. The TDs were on them before they could remount. Those who tried were killed and many others captured.

Recon troops in the same column had a similar experience finding the German crews of heavy, eight-wheeled armored cars resting beside their vehicles. The French had just captured the men and their machines when a Panzer IV and a Panther arrived. Both were destroyed by the Greyhound’s 37mm guns.

Audacity paid off in other ways. After the failure of the German counteroffensive at Mortain, Hitler ordered another attack into the weakly-held west flank of Third Army. The rapid advance of Third Army and its threat to close off the Falaise Pocket made it necessary for the Germans to instead commit the forces to slow that advance.

After a few weeks in combat, it was clear that Leclerc and his cadre had put together a very effective fighting force. Once in combat, their learning curve remained steep and their already satisfactory performance continued to improve.

They were receiving plentiful American-supplied equipment whose quality was a far cry from the obsolete and sometimes barely functional gear they struggled with in Africa. American C rations were also an improvement and, better yet, the rations included coffee and cigarettes. Even the Cs could be traded for the occasional rabbit or chicken. More recruits poured in and were sent to England to be quickly trained, equipped, and sent back to the division.

Leclerc’s division had repeatedly prevailed against German forces fighting desperately for their survival. During the Normandy campaign, it captured 8,800 prisoners and claimed to have destroyed more than 100 tanks, another hundred artillery pieces, and 700 other vehicles.

What followed was a confusing period during which Allied troops north and south of the Falaise Pocket gingerly moved forward, attempting to close off the German escape routes without friendly-fire casualties. The 2nd French Armored and the rest of the Allies moving north were ordered to halt at Argentan. Leclerc the cavalryman hated it. Also, he was becoming preoccupied by the lure of Paris.

When one of his combat commands was detailed to support the attack intended to finally close the pocket, he grudgingly complied, but not before annoying Patton’s chief of staff, Maj. Gen. Hugh Gaffey, with his insubordination. Gaffey planned to seal off the pocket with an attack by the 90th U.S. Infantry Division, supported by a combat command from Leclerc’s division.

Leclerc saw serious flaws in the plan, but Gaffey would not accept Leclerc’s criticism that the plan was “inexecutable.” (The attack was suspended but later revived by the 2nd’s new Corps commander, Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow, in a much better thought-out form.)

With the breakout and the collapse of the pocket, it seemed to Leclerc and the rest of the Free French that the time had come for them to liberate Paris.

The Allied high command had trouble understanding their urgency. De Gaulle and Leclerc knew that the communists with their decades of experience in underground operations had, in many places, become the strongest faction in the French Forces of the Interior (FFI). Their hostility to the rest of the FFI led them to shoot up chateaus, simply because they were occupied by “aristos” (aristocrats). If they got control of public buildings in Paris, it might ignite a civil war that would cripple the Allied effort.

The communist leadership declared they were willing to see 200,000 Parisians killed if it gave them control of Paris. There was also the threat that if Parisians revolted prematurely, Hitler would order the city destroyed, as he had done with Warsaw.

Leclerc began planning to liberate Paris with or without authorization. French supply officers began accumulating gasoline for the march. Leclerc formed an advance guard by inconspicuously withdrawing a few men and vehicles from each of his combat commands and quietly sent them off toward Paris while he lobbied his chain of command for orders to send the division.

While Leclerc was lobbying, the Paris police went on strike and the insurrection in Paris began with a rising by those police who occupied the Préfecture of Police. The communists soon joined and began attacking individuals and small groups of Germans. The next day the Germans began to prepare to recapture the Préfecture. A truce was negotiated. It held less than 24 hours before the communists denounced it and the fighting resumed.

Meanwhile, Gaullists in the city convincred Eisenhower in a meeting on August 23 that the Allies needed to support the insurrection. Leclerc was on his way.

He formed his division into two main columns to attack from the southwest and south. Aided by locals who knew the minor roads and byways, the division moved out. By the morning of August 25, the division had spread through the western part of the city attacking scattered German forces; simultaneously, the American 4th Infantry Division was moving into the city from the southeast.

At one point, a Sherman at one end of the Champs Élysées was fired on by a Panther at the far end. The commander ordered the gunner to set his sights for 1,500 yards. The gunner, a Parisian, knew the park was 1,800 yards long. He set his sights accordingly and hit the panzer with his first round. Late that day, the German commander, General Dietrich von Choltitz, formally surrendered the city.

Paris was not won cheaply. The march on the city and the action there cost Leclerc’s division 14 percent of its men killed or wounded—more than the rest of the campaign in France.

The 2nd French Armored—and the French divisions that had landed on the Mediterranean coast—would serve with distinction in the liberation of eastern France. Leclerc’s best days as a field commander were still ahead of him. But the 2nd’s liberation of Paris began the rebirth of the French Army’s pride that had been shattered in 1940.

The 2nd spent a few days giving new recruits basic training while maintaining, repairing, and absorbing new equipment, including a consignment of Gnome et Rhône motorcycles originally intended for the Wehrmacht. The factory workers had made sure they would quickly break down and the division was soon calling frantically for spare parts.

De Gaulle wanted the 2nd to stay while he consolidated his control over Paris, but any delay would give the Germans time to reorganize. So, after a few days, the 2nd moved north and east toward the Marne River—the right flank of Patton’s Third Army.

The division advanced with the 79th U.S. Infantry Division on its left, its right flank in the air. The main opposition was from over-age guard troops and security battalions. The Germans hoped to stabilize the front long enough for the Fifth Panzer Army to mount a counterattack, but the Americans and the French were defeating the scattered defenders in detail. Something had to be done. On September 12, a new German unit, Panzer Brigade 112, entered the battle.

Panzer brigades, ad hoc brigade-sized units, had served on the eastern front since early in the war, sometimes with considerable success. In the fall of 1944, Hitler decided that rather than sending all the new armored vehicles to depleted panzer divisions where experienced panzer crewmen were often without tanks, he would create new panzer brigades.

Units made up mostly of tanks could sometimes be successful in places like the plains of Russia or when winter weather had grounded air support. But in WWII, tanks were usually best employed as part of a combined-arms team that contained artillery, tank, and infantry battalions in roughly equal numbers. The 112th had two battalions of tanks, and a battalion of panzer grenadiers, but there was no reconnaissance unit, engineers, field, or air-defense artillery, and only a limited tank-recovery and repair unit.

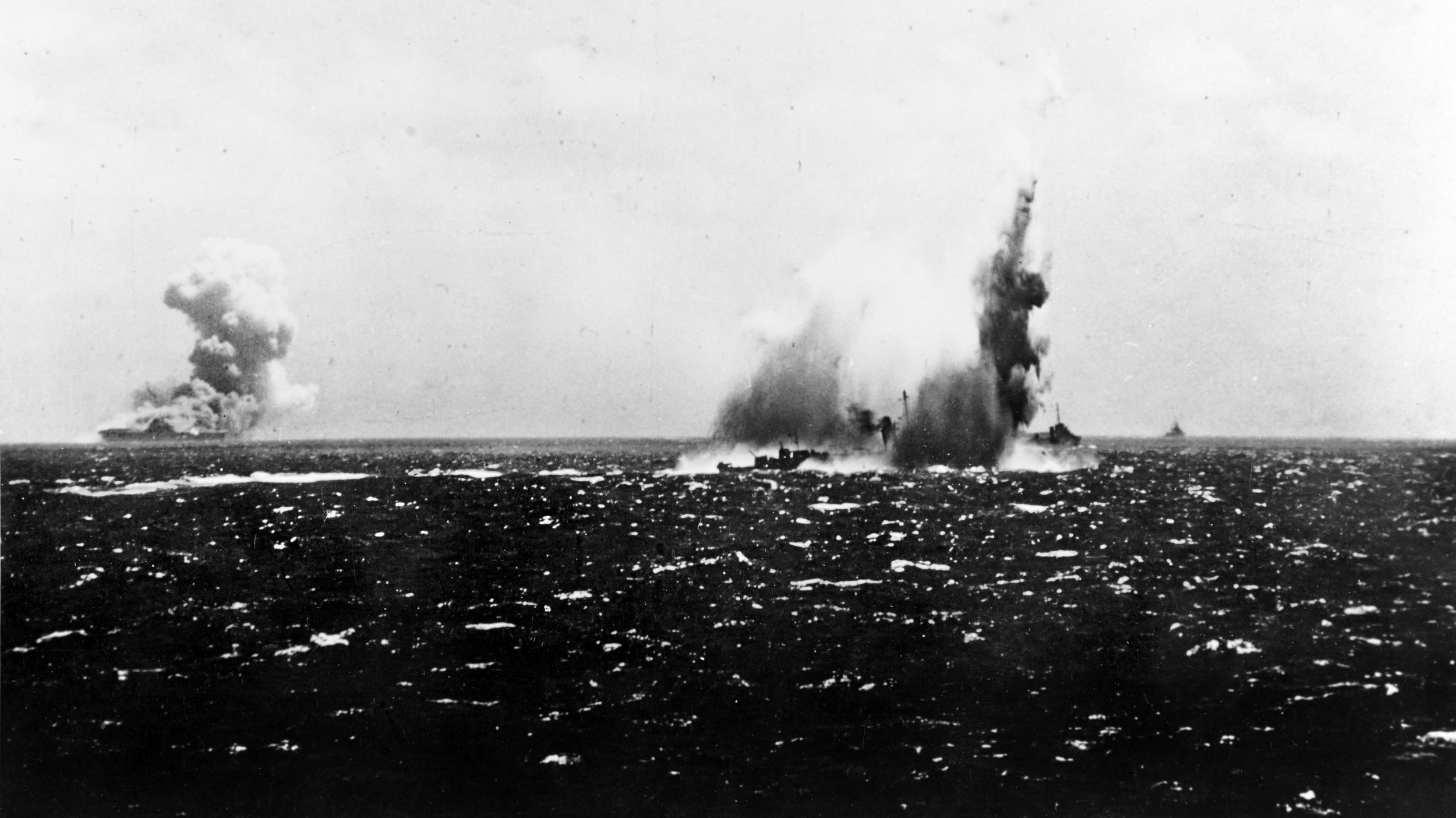

The brigade was ordered to wheel around the right flank of Third Army and roll it up. On a rainy September 12, it headed south in two columns. The western column was the brigade’s Panther battalion and 40 Mark IV Specials. The eastern column had the rest of the brigade’s Mark IV battalion and the bulk of the infantry. To send this unit out with no possibility of significant air support and into an area where both the RAF and American Army Air Corps had powerful ground-attack units was an exceptionally bad decision.

By evening, the western column had reached the village of Dompaire. There was only one road passing through it and it is surrounded by hills which are impassable to vehicles. The inexperienced troops sent out no patrols and set no guards.

Part of Colonel Paul Landglade’s combat command moved in around them. He was badly outnumbered but he had artillery and air support. His plan was to use some of his force to block a German retreat while he attacked down the road toward the other end of the village. He still had a small reserve to guard his rear.

A reconnaissance party that included four TDs drew first blood and hastily withdrew. A feint by armored infantry caused the Panthers to deploy and move forward. They were driven back by heavy fire from Landglade’s tanks and artillery, then blocked from withdrawing by the reserve force to their rear. There was no escape.

The 2nd’s air-support officer called in four air strikes during the course of the battle. After each strike, the French troops moved forward to tighten their hold on the Germans. Eventually they reached a rise on the north edge of Dompaire from which they were able to dominate the whole battlefield.

The commander of the Panthers called for support from the eastern column, but the postmistress of Pierrefitte spotted the approaching column and telephoned Landglade. He ordered his reserve of tanks and TDs to block that advance. In the midst of the German attempt to dislodge that force, an airstrike hit the eastern column which broke up the attack. An assault by the grenadiers was also driven back.

Leclerc sent Landglade reinforcements that arrived late in the day. But when the French attack resumed the next morning, the attackers found the village empty of Germans, the Germans having abandoned their remaining vehicles and fled on foot during the night. The French found 33 burned-out Panthers and four others intact. Together with the losses the eastern column had suffered, the panzer brigade was essentially destroyed.

The war continued to move further north and east. The first tenuous link up with Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch’s Seventh Army that had landed on the Mediterranean coast, was accomplished soon after the battle at Dompaire. The XV Corps was transferred to it. The First French Army under General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny (a.k.a. de Lattre) landed at the same time. Together with the Seventh, they formed the 6th Army Group under General Jacob Devers.

The Vosges Mountains the Allies were approaching are such a serious barrier that there had been no contested crossings in modern times. The northern part of the range, the Low Vosges, is less rugged than the High Vosges to the south, but the range makes up for it by being wider. The Germans were trading space for time while they prepared positions in the mountains.

The defenses were concentrated around the few good routes through them. At the juncture of the High and Low Vosges is the Saverne Gap. It is a narrow valley, easily blocked. To open it, the hills around the pass needed to be taken. Further south in the High Vosges, another route follows the Saales and Hantz passes. The area to the south and east of the High Vosges is open and fairly level until the Jura Mountains in Switzerland are reached.

Near the west end of the Saverne Gap is the city of Baccarat. The German positions around the city blocked access to the Saverne Gap and the 2nd French Armored was ordered to capture it.

The excellent intelligence that always characterized Leclerc’s operations was never more evident when he was planning this operation and the one that followed. As usual he was getting good information from the area’s inhabitants and now he had an additional source.

Beginning with the 1942 invasion of the U.S.S.R., Germany had taken heavy casualties. Just since the invasion of France, the western Allies and the Soviets together had inflicted about 2,200,000 casualties on Germany and bottled up another 200,000 troops in coastal garrisons. As a result, Germany had become very elastic about who was a German and therefore subject to conscription. Anyone from any of the areas annexed by Germany—or anyone in the occupied areas who was arguably of German stock—even if the family spoke no German, was liable for call up.

Few of those conscripted out of any of these areas had any reason to be loyal to Germany and, in the west, many deserted. Those that deserted here brought with them detailed knowledge of German positions. One Ukrainian “German” gave them the precise location of over 30 machine guns. Leclerc had a clear picture of the German defenses.

The Mondon Forest to the north of Baccarat was good tank country in the dry season but by the end of September, Western Europe was beginning to experience its worst winter in living memory. The valleys in the forest were flooded and the few roads were saturated, so German defenses were concentrated south of the city where the access was better.

A careful reconnaissance of the forest identified potential routes that stayed on the relatively dry hillsides. Tracks were cut through the forest along those routes while storms obscured the sound of the work.

Following a feint from the south and an extremely heavy artillery barrage, troops stormed out of the forest and took the German positions from the rear. The attack carried through the town and captured the bridge over the Meurthe river.

For once, a battle plan had survived contact with the enemy. The 2nd made it look so easy that it was referred to as the “ballet héroïque.” The truth was that the victory was the result of meticulous reconnaissance and planning.

Meanwhile, other 2nd Armored troops moved north out of the Mondon Forest and cleared the area for several miles. The whole operation cost the French 120 casualties. German casualties, not including deserters, were about six times that.

By this time, the 2nd was recognized as an elite unit and was getting plenty of recruits who received good training. Leclerc had the training cadre that the division had established in Yorkshire moved to an area near Paris.

The attack at Baccarat was part of Operation Dogface—the effort to clear the area immediately to the west of the Vosges. Attacks by VI Corps units cleared the middle section of the area facing the High Vosges and the First French Army did the same further south. The Germans took heavy casualties attempting to hold the area in front of the Vosges while the defenses in the passes were completed, but too few men were left to adequately man the mountain defenses.

With the objectives of Operation Dogface achieved, it was time to force the Vosges passes. As part of the operation’s planning, Leclerc ordered a plaster terrain model of the whole area sent from Paris. Interrogations of prisoners and interviews of the local resistance continued to build his intelligence. Most of these mountains are heavily forested but they contain a few small hamlets accessed by second- and third-rate roads. Those were easily blocked by mines, a few fallen trees, or a man with a rocket launcher. Leclerc and his staff made an intense study of these roads before the fighting started.

At the Saverne Gap, XV Corps’ 44th Infantry Division would drive through the hills to the north of the pass while the 71st Infantry Division cleared the hills to the south of it.

After the fall of Baccarat, the weather continued to deteriorate. Heavy rains were followed by blizzards. Most streams were flooded and the mud seemed bottomless. The 44th and 79th Divisions jumped off early in the morning on November 13.

They were facing three small Volksgrenadier divisions, deployed in depth in scattered roadblocks and strongpoints; there was no mobile reserve. When a strongpoint was encountered, the first echelon of attackers was to mount a hasty attack. If that did not roll over the position, it was to be bypassed and left for those following. The challenging aspect of the plan was that the rugged terrain could make bypassing difficult.

Leclerc’s men would initially screen the advance on the north and south. When the German positions began to collapse, the 2nd would become the Corps’ exploitation force and attack the retreating Germans.

The 324th and 71st Infantry Regiments of the 44th attacked on the north side of the gap. They only advanced a mile that day and were not doing even that well the next. With gaps between German positions and no mobile German reserve, the 44th’s commander sensed an opportunity. On the 15th, the division’s reserve regiment, the 114th Infantry, slipped between the German front-line positions and swung north, attacking German positions from the flank and rear.

By the next evening, the regiment, aided by a cavalry group, was mopping up German positions and the rest of the division was on the move. On November 18, the attack picked up speed as the German defenses fell. By November 19, the 44th had broken through. That day, the 71st Infantry Division in the lead advanced nine miles.

The 79th’s attack, on the south side of the pass, started forward at the same time as the 44th’s with the 314th Infantry on the left and the 315th on the right. By the next day, they were threatening to drive a wedge between the 553rd and 708th Volksgrenadier Divisions facing them. The 708th moved up its reserve to make a strong counterattack. But elements of the American 315th Infantry, supported by tanks and tank destroyers, assaulted the German assembly area, dispersing the Germans and destroying most of the 708th’s assault guns. The Germans’ other counterattacks were equally ineffective.

On November 16, elements of the 2nd French Armored were committed to provide flank security and speed the attack. South of the Saverne gap the 2nd’s screening force encountered a small force of German alpine troops which held them up overnight. At dawn, an artillery barrage and a tank-infantry assault drove them off.

By November 19, German forces were falling back, unable to hold defensive positions in the face of Allied pressure. Haislip authorized the 2nd to switch to exploitation; its attack began on November 20.

Leclerc’s careful reconnaissance and planning paid off. Each combat command was divided into its two subgroups; each subgroup was assigned primary and alternative routes through the mountains. The movement was so rapid that his troops got behind the German positions at the east end of the gap. By that time, there was a 10-mile breach in the German lines. German weakness encouraged Leclerc to widen the breach further.

One of his columns swung further north through La Petite Pierre and out onto the Alsatian Plain. By the time the German troops realized what was happening, 2nd Armored troops were seizing the exits from the mountain passes on both sides of the gap. Others were headed for Saverne.

To the south, VI Corps was moving down the eastern slopes of the Vosges. Further to the south, the First French Army successfully deceived the Germans about the location of their own attack and, in hard fighting, cleared the lower third of the range. They then advanced north along the Alsatian plain nearly to the city of Colmar.

Early on November 23, the 2nd started for Strasbourg. One subgroup screened to the north and the reconnaissance regiment to the south. The rest of the division, minus a reserve, started for the city by several routes. Saturated soil and scattered German defenses made it hard going to the west and south of the city. But, by 9:30, the troops moving in from the north crossed into the city boundary—a move reminiscent of the liberation of Paris, with jubilant chaos and Germans in enclaves scattered through the city.

The campaign was costly for the Germans. The 2nd Armored alone claimed 2,000 killed and 12,500 captured, with hundreds of tanks and other vehicles destroyed.

The 2nd fought one more major action and, for the first time, it worked closely with other French units that had a very different experience from the 2nd. Leclerc’s troops had always worked with American formations and drew their rations and other supplies from American supply sources while much of the supplies for the rest of the French units were offloaded at Mediterranean ports and turned over to the French.

The collapse of the German forces in western and southern France had suddenly moved the front hundreds of miles from those ports and made keeping Allied troops in northeastern France supplied much more difficult.

All of the units in northeastern France were experiencing shortages. Patton’s divisions fighting to the west of Devers’s 6th Army Group were receiving about 300 tons of supplies per division a day; the allocation should have been around 900 tons. The French were sometimes allocated less than similar American units. The French resented that—and that the 2nd was better supplied. As General de Lattre chided one of Leclerc’s officers, “There must be no more of the 2nd getting twice as many cigarettes as First Army.”

There were other sources of friction. The commanders and their staff lived well while the troops were hungry and ill clad. Many Free French despised the leaders that had remained loyal to Vichy. In particular, Leclerc despised de Lattre. This appears unfair since he was the only Vichy commander who ignored Vichy’s order not to oppose the German takeover of southern France; he joined De Gaulle soon thereafter.

And finally, Leclerc had his own training establishment and recruits pouring in. With most of the pre-war French Army prisoners in Germany, the rest of the French units were having a difficult time replacing their heavy losses with reliable troops. De Lattre was reduced to integrating whole units of FFI troops, which had little training or discipline, into existing divisions. Equipment shortages were so severe the undertrained 10th (Paris) Infantry had to be armed with captured German weapons.

When the Allies forced their way across the Vosges, the Germans retained control of the area around the city of Colmar—the “Colmar Pocket” as it became known. Ike wanted the whole west bank of the Rhine cleared before crossing that river, but the pocket was a tough nut. Hitler had poured troops, including a panzer brigade and more artillery, into the perimeter. Being so close to the Saar industrial area meant that, for once, their artillery was well supplied. The French, still at the end of a long shaky supply line, were not.

Devers left the task of capturing the pocket to the First French Army, but that force simply did not have the power to dislodge the Germans. As the winter continued, heavy casualties and growing problems with sickness ground French strength down. After the Battle of the Bulge, Ike insisted it was time to clear the pocket.

The plan was to focus attacks from north and south in the areas nearest the Rhine River. The 2nd French Armored was assigned to attack from the north as part of Lt. Gen. Joseph Monsabert’s II French Corps.

It is not good tank country. It is laced by streams and canals and there were enough forested areas to cloak German anti-tank guns and counterattack assembly areas. More infantry than the 2nd’s three battalions were needed. As they pushed a finger southward, taking heavy losses, Leclerc became concerned about his men’s exhaustion and the long, poorly guarded flank that was growing on his right.

Leclerc insisted to General Monsabert that his troops were too worn down to clear woodland on his flank. He needed at least two battalions of fresh infantry to do that job. Monsabert disagreed and demanded Leclerc put his objections in writing.

De Lattre was furious, and his tirade at Leclerc was remarkably petty. Leclerc declared that he would no longer serve under him and got permission to take the matter to Jake Devers, the 6th Army Group’s commanding general.

It became clear to Devers that the French alone were too weak. Devers left the French 2nd next to the Rhine and moved two American infantry divisions in between it and the rest of the French troops.

It remained a tough conflict. Hitler had issued one of his fight-to-the-last-man orders that had cost Germany so many unnecessary casualties. The awful weather grounded the Allies artillery spotter planes that usually directed American counter-battery fire, so the German artillery could fire with impunity. But by February 7, the remaining German troops were surrounded and cut off from the Rhine. When the surrender came, 80 percent of the German troops who had held the pocket were either killed or captured.

But before this happened, the Germans launched their last major offensive in the West: Operation Nordwind. The 2nd was one of the units pulled into reserve to meet it. The offensive ultimately failed, but not without causing a major command crisis. Ike did not at first understand the importance to French morale of holding Strasbourg, and ordered Devers to withdraw his troops back to the Vosges Mountains. De Gaulle, Churchill, and even Patton questioned his decision until Ike finally agreed that Devers should stop the Germans well short of the city.

After Nordwind, the 2nd French Armored went into reserve near Paris for rest and rebuilding. While fighting continued along the German border, other French units were cobbled together to keep contact with German garrisons holding French ports on the Atlantic. The French were mostly content to pin the Germans in their fortifications.

The exception was the Gironde Estuary, where de Gaulle wanted to open a port to help revive French overseas trade. A battle group of the 2nd was assigned to provide artillery and armored support to the attackers. The German garrisons surrendered on April 18; Germany surrendered May 8, so the sacrifice of lives is questionable.

The 2nd Armored’s last action in WWII involved overrunning Germany as the last defensive lines crumbled. There was no pressing military need to add it to the forces moving across Germany, but the division deserved to be in on the kill.

Leclerc continued to serve France until his death on November 28, 1947, in an airplane crash in Algeria. But he is best known for creating a unit that had a proud record of achievement.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments