By Michael E. Haskew

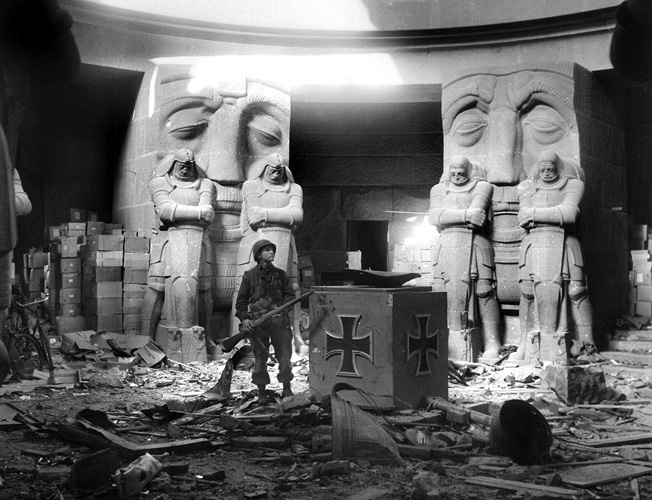

In October 1813, the combined allied armies of Russia, Austria, Prussia, Sweden, Saxony, and Württemberg met and defeated the French Grand Armee under Napoleon Bonaparte at the German city of Leipzig, forcing him to retreat and hastening his eventual abdication and exile to the island of Elba. Some 600,000 soldiers took part in the momentous battle. A century later, the German people commemorated the great victory in the Völkerschlacht, or Battle of the Nations, with the construction of a huge monument, the Völkerschlachtdenkmal, that was completed in time for the centennial of the battle.

One of the tallest monuments in Europe, the Völkerschlachtdenkmal rises 299 feet and occupies a square base 417 feet by 417 feet. Nearly 27,000 granite blocks and tons of concrete and sandstone were used in the construction of the two-story edifice, which includes a crypt and 500 steps to a viewing platform at its top. Adorned with figures mourning the sacrifice of the dead in the Battle of the Nations and celebrating the triumphant will of the German people, the monument was constructed like a massive, thick-walled fortress. In April 1945, as World War II came to an end, the monument actually became one. How that happened is a story in itself.

Montgomery’s Intentions to Take Berlin

For months, the Allied rallying cry in the West had been “On to Berlin!”

From D-Day through the hedgerows of France, the breakout, and the pursuit across the German frontier, British and American commanders and their troops had looked forward to the day that the Union Jack and the Stars and Stripes would be raised in triumph in the capital of a defeated Nazi Germany.

Now, in the final days of World War II with the Third Reich in its death throes, Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower, architect of

the broad-front strategy, skirted protocol a bit and cabled Soviet Premier Josef Stalin directly. On March 28, 1945, he forwarded a message to Maj. Gen. John R. Deane, the U.S. military liaison in Moscow, and three days later the communiqué was in the Soviet dictator’s hands.

It read in part, “My immediate operations are designed to encircle and destroy the enemy forces defending the Ruhr. My next task will be to divide the remaining enemy forces by joining with your forces…. Before deciding firmly on my plans, it is, I think, most important they should be coordinated as closely as possible with yours both as to direction and timing. Could you, therefore, tell me your intentions and let me know how far the proposals outlined in this message conform to your probable action. If we are to complete the destruction of German armies without delay, I regard it as essential that we coordinate our action and make every effort to perfect the liaison between our advancing forces. I am prepared to send officers to you for this purpose.”

By the end of March, the Allied XXI Army Group under British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery had completed Operation Plunder and was across the Rhine in strength. Monty’s next move, he believed, was to be a massive eastward offensive against the German capital 250 miles away. Meanwhile, the American XII Army Group, commanded by Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley, had crossed the Rhine more than two weeks earlier, particularly leveraging a bridgehead across the great river at Remagen.

Montgomery’s setpiece victory in the north had been ponderously slow in developing. Despite his March 27 message to Eisenhower, “Today I issued orders to army commanders for operations eastward which are about to begin,” and expressing his intent to cross the Elbe River swiftly and drive “thence by autobahn to Berlin, I hope,” some high-ranking staff officers estimated that he would need several weeks of preparation for a renewal of offensive operations.

Berlin: “A Prestige Objective”

Early in March, Eisenhower received word that the Soviet Army was across the Oder River, in some places less than 30 miles from Berlin. On March 19, the supreme commander invited Bradley to accompany him to Cannes, on the French Riviera, for a few days of rest and relaxation. While there, Eisenhower sought the perspective of his old comrade and fellow member of the U.S. Military Academy graduating class of 1915.

Eisenhower asked Bradley what he thought about a final, all-out push for Berlin. Bradley responded that the effort would cost 100,000 casualties and added wryly that it was “a pretty stiff price to pay for a prestige objective, especially when we’ve got to fall back and let the other fellow take over.”

True enough, though symbolic of the Nazi evil, Berlin held little strategic military value. Further, the “Big Three”—U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and Stalin—had sealed the deal that designated prescribed Allied occupation zones in Germany after the end of the war. Berlin was 100 miles deep in the Soviet zone. It stood to reason that American and British blood should not be shed for the German capital if it was to be subsequently relinquished to the Soviets. There was also talk of diehard Nazis, many of them battle-hardened men of the SS, moving into the Harz Mountains and establishing a national redoubt from which to carry on a guerrilla war that might last for years.

Above all, Eisenhower strove to fulfill his mission to prosecute the war with military rather than political objectives in mind. His communication with Stalin was not altogether improper. He had been authorized to discuss purely military issues with the commanders of Allied troops, and Stalin was the commander in chief of all Red Army forces. Churchill and Montgomery howled disapproval, but Eisenhower prevailed with the solid backing of U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall.

His mind made up, Eisenhower rankled the British once again by removing Maj. Gen. William Simpson’s Ninth Army from Montgomery’s command and returning it to Bradley and XII Army Group for upcoming operations. It was clear to Montgomery that the focus of Allied offensive efforts was shifting southward to the Americans. Eisenhower had long managed the difficult task of balancing the Anglo-American alliance, a tall order given the often-prickly relations between his lieutenants. This decision, however, was true to form—the right choice given the exigencies of the military situation.

The High Cost For Berlin

Berlin would be left for the Soviets to conquer—and shed blood for. British and American troops would halt at the Elbe River and link up with the Soviets there. Territory seized by Eisenhower’s command and slated for postwar occupation by the Soviets would be vacated at the appropriate time. Not surprisingly, some American field commanders, particularly Simpson, were dismayed that they were not to be allowed to advance on Berlin. Nevertheless, they followed orders.

In his response to Eisenhower, Stalin confirmed that American commander’s course of action “coincided entirely with the plan of the Soviet high command.” Almost as an afterthought, he added, “In the Soviet high command plans, secondary forces will therefore be allotted to Berlin.”

In reality, Stalin mistrusted his Western allies. Red Army forces were already being marshaled for the conquest of the Nazi capital. By the time the fight for Berlin was over, the Soviets had suffered at least 80,000 dead and nearly 300,000 wounded. Some estimates are higher.

Striking Into the Heart of Germany

On March 25, just two days after the first of Montgomery’s troops set foot on the east bank of the Rhine, seven divisions of the U.S First Army under Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges struck eastward from Remagen, spearheaded by Maj. Gen. Maurice Rose’s 3rd Armored Division. Simpson’s Ninth Army jumped off from positions around the German city of Wesel with Maj. Gen. Isaac White’s 2nd Armored Division in the lead. The two pincers would converge some 70 miles eastward near Lippstadt and Paderborn, trapping German Army Group B in the Ruhr, the industrial heart of the Reich.

Completing their lightning run, elements of the two armored divisions met at Lippstadt about 1 pm on Easter Sunday, April 1. Surrounded in the Ruhr Pocket, some 30 miles by 75 miles, were more than 300,000 German soldiers, including the headquarters and support troops of Army Group B, most of the Fifteenth Army, two corps of the First Parachute Army, and all of the Fifth Panzer Army.

Eisenhower weighed his options. Bradley allocated 18 divisions to the reduction of the Ruhr Pocket and readied his remaining 30 divisions for the next move. The bulk of the First and Ninth Armies were directed to continue their eastward advance across central Germany and to the Elbe. Montgomery was ordered to advance in the north, protecting the left flank of the XII Army Group. The U.S. Third Army, under General George S. Patton, Jr., continued driving southward toward the German city of Chemnitz and the Czech border, while the Sixth Army Group attacked farther south and the Seventh Army thrust toward the Austrian frontier, capturing the city of Nuremberg, site of Hitler’s massive Nazi Party rallies of the 1930s, on April 20.

“You Must Stop on the Elbe”

For reasons that were never made perfectly clear, perhaps to preserve their fighting spirit, Eisenhower chose to withhold his decision not to advance on Berlin from virtually all of his senior commanders except Bradley. On April 4, the day Ninth Army was officially returned to XII Army Group command, Bradley maintained that his subordinates were to endeavor to cross the Elbe and even ordered Simpson to “exploit any opportunity for seizing a bridgehead over the Elbe and be prepared to advance on Berlin or to the northeast.”

The veteran 2nd Armored Division again led Simpson’s thrust; by April 12, Ninth Army had crossed the Elbe at Magdeburg, only 50 miles from Berlin. As Simpson sought permission to continue toward the German capital, he was taken aback by Bradley’s response.

“My people were keyed up,” Simpson remembered. “We’d been the first to the Rhine, and now we were going to be the first to Berlin. All along we thought of just one thing—capturing Berlin, going through and meeting the Russians on the other side.”

Bradley telephoned Simpson on April 15: “I’ve got something very important to tell you, and I don’t want to say it on the phone,” the XII Army Group commander said. When the two generals met at Wiesbaden, Simpson was carrying his detailed plan for the advance on Berlin.

Then, Bradley stopped him cold. “You must stop on the Elbe,” he said flatly. “You are not to advance any farther than Berlin. I’m sorry, Simp. But there it is.”

The First Army’s Advance

Hodges’s First Army was tasked with the main American thrust, directly east toward the cities of Dresden and Leipzig in Saxony. For the offensive, Hodges fielded two corps: to the left was the VII under Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins consisting of the 1st and 104th Infantry Divisions and the 3rd Armored Division, and on the right was V Corps under Maj. Gen. Clarence Huebner and including the 2nd and 69th Infantry and 9th Armored Divisions. Eventually, Dresden was occupied by the Red Army following the German surrender. However, the American advance on Leipzig precipitated an unusual series of events.

On April 5, First Army resumed its eastward drive. Huebner’s V Corps was led by the 69th and 2nd Divisions, under Maj. Gens. Emil F. Reinhardt and Walter M. Robertson, respectively. After two days of fighting against the German LXVII Corps, the best of their patchwork Eleventh Army, the 69th Division had advanced from Kassel and crossed the Werra River. Against lighter opposition, the 2nd Division was across the Weser River in little more than 24 hours. On April 7, troops of the 2nd Division pressed six miles beyond the Weser. Concerns that the Germans were preparing a substantial defense in the vicinity of the Weser faded.

On April 8, both V Corps infantry divisions crossed the Leine River near Göttingen, and the following day they advanced another 10 miles against only token resistance. Troops of the 2nd Division discovered a prison camp at Duderstadt and freed 600 prisoners, including 100 Americans. Meanwhile, the 69th occupied Heiligenstadt.

The Flak Cannons of Leuna and Leipzig

To date, Bradley had been concerned that his combat units maintain a coordinated front as they advanced. However, on April 10, he lifted all restrictions on eastward movement. Huebner shifted the 9th Armored Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. John W. Leonard, to spearhead the V Corps drive. In Collins’s VII Corps, the 3rd Armored Division, under the command of Brig. Gen. Doyle Hickey after the death of General Rose near Paderborn at the end of March, led the way.

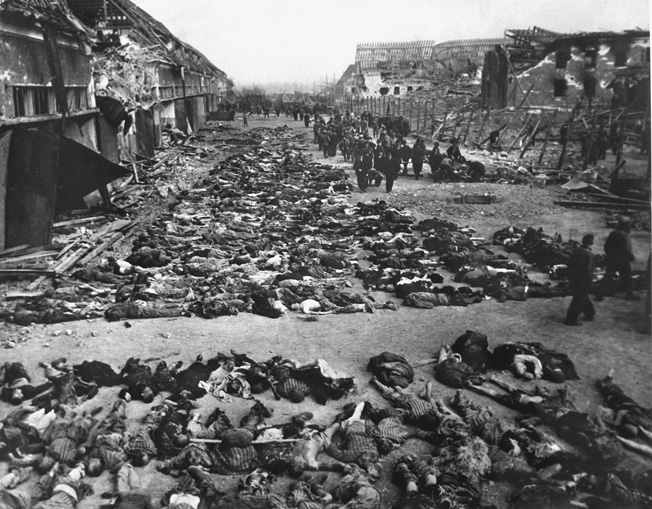

Both divisions made significant progress as the 3rd Armored Division liberated the Nordhausen concentration camp on April 11, where a corpsman of the 329th Medical Battalion observed, “Rows upon rows of skin-covered skeletons met our eyes…. Their striped coats and prison numbers hung to their frames as a last token or symbol of those who enslaved and killed them.”

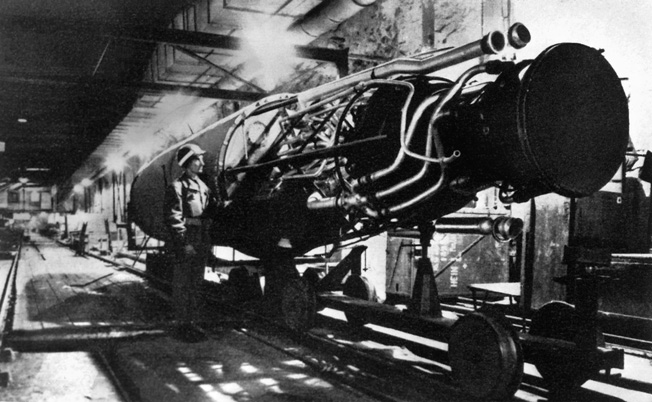

The tankers waited for fuel, and in the meantime found a slave labor camp with a capacity for 30,000 workers, none of whom appeared to have been left alive, and a large underground manufacturing facility that produced engines for the dreaded V-2 rocket that terrorized London and other cities in the waning months of the war.

As the V Corps vanguard approached the Saale River, its northern shoulder came under fire from German antiaircraft weapons, their crews directed to depress their firing angles to hit the American armored formations. The 9th Armored Division lost nine tanks to the accurate fire before the guns were silenced. Apparently, the Germans had concentrated several rings of antiaircraft weapons in the region—not to defend the cities, but to guard synthetic oil refineries and numerous industrial facilities in the vicinity. Reports indicate that 374 heavy flak weapons were in the area, 104 of them around the city of Leuna and 174 around Leipzig.

Since the spring of 1944, the 14th Flak Division had been headquartered in Leipzig. Grouped in batteries of 12 to 36 guns, they ranged from 75mm to heavy 128mm weapons. Early in the war, the German 88mm antiaircraft gun had proven deadly against ground targets, and the flat terrain surrounding Leipzig offered excellent fields of fire. The area had been known to Allied airmen as “Flak Alley” for some time; however, no one had found it necessary to inform the advancing infantry and armor of the menace that awaited them.

General Huebner concluded that the flak guns were the outer band of the defenses of Leipzig. He ordered the 9th Armored Division to move 13 miles southeast, around the city and to the banks of the Mulde River. The 2nd Infantry Division was to continue directly eastward toward Leipzig, while the 69th was ordered to follow the 9th Armored and then enter the city from the south and southwest.

Cutting Off Leipzig

General Leonard’s tanks ran into stiff resistance at the Saale River near the town of Weissenfels and rerouted to cross the waterway on an intact bridge to the southwest. That same day, April 13, the tanks neared the town of Zeitz and rolled over the Weisse Elster River. Breaking through the deadly ring of flak guns, Combat Command Reserve (CCR) of the 9th Armored raced to the Mulde River, 20 miles southeast of Leipzig, on April 15.

On the 16th, CCR entered Colditz and liberated the 1,800 Allied prisoners of the infamous Oflag IV-C, better known as Colditz Castle, which held a number of famous and high-ranking officers, some of whom had been transferred there because of repeated attempts to escape. With the capture of Halle in the Harz Mountains two days later, Leipzig was effectively cut off.

Meanwhile, the 271st Infantry Regiment, 69th Division secured Weissenfels during some spirited fighting on April 13-14, killing or capturing many of the 1,500-man garrison and then crossing the Saale in small boats. On the 15th, elements of the 2nd Division captured Merseburg and occupied numerous small towns in the area. As one regiment crossed the Saale after dark on a railroad bridge that was damaged though still standing, other infantry units crept close enough to the German antiaircraft guns to radio coordinates to their own artillery and bring accurate fire on the positions, finally destroying many of the enemy weapons.

The Allied noose around Leipzig, Germany’s fifth largest city with 750,000 inhabitants, was tightening. Leipzig had long been revered for its historical significance and as a center of German culture, higher education, trade, and industry. Martin Luther had led the congregation of the St. Thomas Church there; composer Johann Sebastian Bach played the organ in the same church for more than 25 years and was buried on the grounds. Composer Richard Wagner was born in the city. And in Leipzig the Völkerschlachtdenkmal was built to commemorate a great victory. It was inevitable that the monument would become the scene of Germany’s last stand.

Poncet vs Grolmann: A Fanatic Against a Realist

Colonel Hans von Poncet commanded the relative handful of German defenders in Leipzig, which included troops of the 14th Flak Division, some of whom had lost their antiaircraft weapons and were now serving as infantry, 750 men of the 107th Motorized Infantry Regiment, a motorized battalion of about 250 soldiers, some Hitler Youth, and several battalions of the Volkssturm, mostly old men and boys who had been forced into the Army as a home guard when the fortunes of war turned decidedly against Germany.

One sizable unit that Poncet did not control was the 3,400-strong Leipzig police force. The policemen, paramilitary in their own right, were firmly under the command of Brig. Gen. of Police Wilhelm von Grolmann.

Grolmann decried Poncet’s willingness to employ the Volkssturm and considered it tantamount to murder. He saw nothing to be gained in a futile defense of the city. Hoping to spare Leipzig from destruction, Grolmann was particularly concerned about damage to the city’s electrical and water supplies if the bridges over the Weisse Elster River were destroyed to slow the Americans. Poncet couldn’t have cared less; he was determined to fight and fortified numerous buildings around the city hall and later withdrew into the Battle of the Nations Monument with about 150 men, some of whom were later described by the Americans as SS troops.

While Poncet plotted his own Götterdämmerung, Grolmann was trying his best to surrender the city. Late on the afternoon of April 18, Grolmann miraculously made telephone contact with General Robertson of the 2nd Division and offered to capitulate. As the news was passed up the American chain of command from Huebner to Hodges, Grolmann got Poncet on the telephone and was told curtly, just prior to the click of a hangup, that Poncet had no intention of surrendering.

Charles MacDonald Attempts to Negotiate the Surrender of Leipzig

By this time, Hodges had responded that only the complete, unconditional surrender of Leipzig was acceptable. Then, an already strange series of events became even more bizarre. Despite Poncet’s intransigence, Grolmann sent a junior officer to the closest Americans he could find. In the gathering darkness, the emissary was shuffled into the command post of Company G, 23rd Regiment, 2nd Division and the presence of its commander, Captain Charles B. MacDonald.

At the tender age of 22, MacDonald was a combat veteran of the Battle of the Bulge, the Hürtgen Forest, and the campaign into the Third Reich. In later years, he became an acclaimed author and deputy chief historian for the U.S. Army, writing and supervising the preparation of several volumes in the official series United States Army in World War II, popularly known as the Green Book Series. Among his other works are the quintessential reminiscences of a young officer in combat, Company Commander, and A Time for Trumpets: The Untold Story of the Battle of the Bulge. MacDonald authored The Last Offensive, the volume of the official history containing the story of the fall of Leipzig and downplayed his role in it. In Company Commander, however, he remembered a wild night of cat and mouse, cloak and dagger, and outright comedy.

“Now wait a minute,” MacDonald remembered asking the excited soldiers who had brought in the German officer. “Does he know I’m just a captain? Will he surrender to a captain?”

“A captain’s good enough,” another soldier said. “The Oberleutnant [first lieutenant] here came along so you’d believe us. He’ll tell you.”

“He [the other American soldier] spoke to the German officer in German mixed with gestures, mostly gestures, and the Oberleutnant looked at me and smiled widely, shaking his head up and down,” MacDonald recalled, “and saying, ‘Jawohl! Jawohl! Ist gut! Ist gut!’”

Only the regimental executive officer was available for any higher direction, and he told MacDonald to give it a try. The young captain went first to see a German major and several other officers, dressed in clean, neatly pressed uniforms, inside the city. When MacDonald was not convinced, the major offered a bottle of cognac. After a drink, MacDonald, another American officer, the German major, and their chauffeur embarked on a wild nocturnal ride in a sleek Mercedes Benz—to see Grolmann.

MacDonald was fearful of being shot by German sentries and by his own men. Finally, he arrived at Grolmann’s headquarters. In contrast to MacDonald, dressed in a filthy uniform and with a scruffy beard, Grolmann was “even more immaculately dressed than the others, a long row of military decorations across his chest. His face was round and red and cleanly shaven. A monocle in his right eye gave him an appearance that made me want to congratulate Hollywood on its movie interpretations of high-ranking Nazis.”

Grolmann offered to surrender but acknowledged that he had no control over Poncet. Still, he pressed MacDonald for a guarantee that the Americans would not attack. Finally, MacDonald, Grolmann, a staff officer, and the general’s civilian interpreter were on their way in Grolmann’s open-top car to the confused American captain’s battalion headquarters. Once they arrived, the situation was out of MacDonald’s hands. As it turned out, the surrender effort was noble but fruitless. There was already some fighting in Leipzig.

The Battle of Leipzig

Forward elements of the 2nd and 69th Divisions entered Leipzig on April 18. The 2nd encountered some resistance along the Weisse Elster River, but the bridges remained intact. A few Volkssturm and Wehrmacht soldiers made a stand behind a roadblock of overturned trolley cars filled with large rocks but were rapidly subdued. Spearheaded by an armored task force of the 777th Tank Battalion under the command of Lieutenant David Zweibel, troops of the 69th advanced into Leipzig from the south at 5:30 pm and ran into determined resistance at Napoleon Platz, where the monument was located.

As Zweibel’s armor neared Napoleon Platz, the tankers were greeted with a hail of small-arms fire and rounds from panzerfaust antitank weapons. One Sherman tank was disabled, and the supporting infantry took a number of casualties. Eager to get out of the line of fire, the tanks picked up speed and rolled at nearly 30 miles per hour down the streets toward the city hall; some infantrymen riding atop the armored vehicles were actually thrown off. Faulty maps caused the attackers to overshoot city hall and placed them in a precarious position, unable to advance or fire on nearby German positions. After dark, the tanks were withdrawn.

The following morning, Zweibel again assaulted the center of Leipzig, firing at city hall and the surrounding buildings from a range of only 150 yards. Just after 9 am, following several frustrating attempts to secure the area, Zweibel sent Leipzig’s fire chief into city hall with a surrender demand. The note read that the Germans must surrender if they wanted to avoid a heavy artillery bombardment followed by an all-out assault with tanks, flamethrowers, and a division of infantry; the attack would begin in 20 minutes. Nearly 200 Germans walked out of city hall with their hands up. Inside, the bodies of Mayor Alfred Frieberg and his wife, City Treasurer Kurt Lisso and his wife and daughter, and several others who had committed suicide were found.

Standoff at the Völkerschlachtdenkmal for the Battle of the Nations

However, Leipzig was not completely subdued. The drama at the Völkerschlachtdenkmal remained to be played out. On the morning of April 19, Poncet was still defiant. His small force occupied a nearly impregnable position. Heavy artillery shells did little damage to the sturdy walls of the monument, and the Germans inside were holding 17 American prisoners. Because there were Americans inside, General Reinhardt decided against using flamethrowers to burn the Germans out.

As the standoff wore on, Captain Hans Trefousse, an interrogator of German prisoners with the 273rd Infantry Regiment, persuaded his commanding officer, Colonel C.M. Adams, to allow Trefousse to attempt to persuade Poncet to surrender. Trefousse had been born in Frankfurt, Germany, in 1921 and emigrated to the United States with his parents at the age of 13. He graduated from City College of New York with a Phi Beta Kappa key and joined the U.S. Army when war broke out.

At 3 pm on the 19th, Trefousse, a German prisoner, and the executive officer of the 273rd Regiment, Lt. Col. George Knight, approached the monument under a flag of truce. When Poncet and two other German officers met them, Trefousse pointed out the hopelessness of the situation but Poncet responded that he was under a direct order from Hitler not to surrender. He did, however, agree to a two-hour ceasefire to allow at least a dozen American casualties to be removed.

Throughout the ceasefire, the two argued in front of the entrance to the monument’s gift shop. At 5 pm, the heated discussion moved inside. While celebrations among the American troops were in full swing elsewhere in Leipzig, the grim exchange at the monument continued past midnight.

“If you were a Bolshevik,” Poncet sneered, “I wouldn’t talk to you at all. In four years, you and I will meet in Siberia.”

Trefousse retorted, “If that is true, wouldn’t it be a pity to sacrifice all these German soldiers who could help us against the Russians?”

Terms of Surrender

As it seemed the impasse would never be resolved, Trefousse extended one last option. If Poncet surrendered and walked out of the Völkerschlachtdenkmal alone, his men could follow one at a time. At 2 am on April 20, the diehard Nazi commander strode out of the main entrance. The pockmarked, damaged monument was secured, but not before some confusion ensued as to the disposition of the newly acquired prisoners.

Word reached Trefousse that only Poncet would be allowed out of the monument and that the rest of the Germans would temporarily remain inside under guard. When Trefousse tried to persuade the captives to accept the change in terms, he offered to try to get them 48 hours’ leave in the city in exchange for a pledge not to escape. One German insisted on the original bargain and was allowed to leave the monument.

Trefousse went to Lt. Col. Knight for permission to grant the 48-hour leave. Knight agreed but insisted that the Germans had to be moved without General Reinhardt getting wind of the compromise. As Knight supervised the disarming of the enlisted prisoners, Trefousse guided more than a dozen German officers through the lines to their homes in Leipzig. When it was time for them to return to captivity, only one failed to appear, although he did leave behind a note of apology.

Leipzig Handed to the Soviets

Leipzig was, at long last, completely in American hands. The infantry of the 2nd and 69th Divisions hurried to catch up with the V Corps armor that was already near the banks of the Mulde River. Garrison troops began to file into the city to initiate its military administration.

For most American soldiers, the fighting was over. They were not going to Berlin. They were simply to wait for the Red Army and extend a tenuous hand to their allies. On April 25, 1945, 1st Lt. Albert Kotzebue of the 69th’s 273rd Infantry Regiment and three soldiers of an intelligence and reconnaissance unit crossed the Elbe in a small boat and met soldiers of a Red Army Guards rifle regiment belonging to the 1st Ukrainian Front. East and West had met amid the ruins of the Third Reich.

In July, the Americans withdrew from Leipzig, retiring westward to the line that marked the designated postwar zones of occupation and the Red Army moved in. For the next half century, Leipzig was one of the principal cities of the communist German Democratic Republic.

Today, after years of neglect and disrepair and the reunification of the German nation, the Völkerschlachtdenkmal has undergone extensive renovation in observance of the 200th anniversary of the first great Battle of Leipzig. It remains an imposing monument, not only to the victory over Napoleon, but also to one of the last battles of World War II.

My father was in the 777th Tank Battalion in the 69th Infantry Division in Leipzig. He was involved in the tank assault on city hall and entered the hall to find the suicides – as well as a ton of money. Told by their Battalion Commander Lieutenant COLONEL David Zweibel that the money was worthless, they used it for toilet paper and to light cigarettes and cigars. Note thtat Zweibel was Lieutenant Colonel, NOT simply a lieutenant.

Hello. Great article. I was reading this because I have a Nazi flag captured by the 302d FA Btln. of the 76th ID. They were in or near this battle. The flag is signed and in very good condition. Was signed in Arnstadt. Call me if you you are interested (I am not selling it or anything, just researching ).

Best regards,

Hans Reigle

(302)331-1122 cell

My father also was in the 777th and participated in this battle. He was in the Reconnaissance Platoon.

My late father was a prisoner of war at espenhain , south of Leipzig

He escaped & found his way to the American forces

On his way he ran into a flak battery , where he talked & smoked with a German artillery sergeant , he pointed out where the American army was , & allowed my father to leave

On getting to the us forces , they nearly shot him, thinking he may be a German ( having a heavy south African accent didn’t help )

He found out that they were having problems with a flak battery ( the one he had been at ) & led the Americans to it

My Grandfather (1st Lt. Dewitt G. Wolf) received his bronze star for valor as a tank platoon leader coming to the aid of the tank platoon that ran into heavy resistance at the train station on the outskirts of Leipzig.

My mother was an 18 year old German in Leipzig, She was dressed up as a GI on an army tank to get through the Russian checkpoint when the Americans left Leipzig. She worked for the US Army in Regensburg, until marrying my dad, an SFC, in 1948.

That’s fabulous.