By Bruce M. Petty & Peter McQuarrie

The coastwatching system that operated throughout the South Pacific islands during World War II was introduced to gather and report early information about the movement of enemy ships and aircraft. The initial fear was of German raiders, which sank merchant shipping and attacked shore installations. However, as the war progressed there was growing concern about the likelihood of war with Japan as well.

Gilbert Islands coastwatching was part of a wider coastwatching network spread across the South Pacific, covering the Fiji Islands, Ellice Islands, Tonga, Samoa, the Cook Islands, and other island groups, including those in the more southerly waters around New Zealand. As a part of the New Zealand contribution to this network, the New Zealand Navy controlled 58 stations on tropical Pacific Islands in addition to another 75 on New Zealand and on its offshore islands.

Fourteen small coastwatching stations were established in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands in mid-1941, all operated by New Zealanders. Nine of these stations were in the Gilberts. The Gilbert and Ellice Islands held key strategic positions situated between the British colony of Fiji in the south and Japanese-held Micronesia in the north. The northernmost station in the Gilberts was at Bikati Islet, on the atoll of Butaritari, only 100 nautical miles south of the Japanese-controlled Marshall Islands. John M. Jones was the coastwatch radio operator at this station.

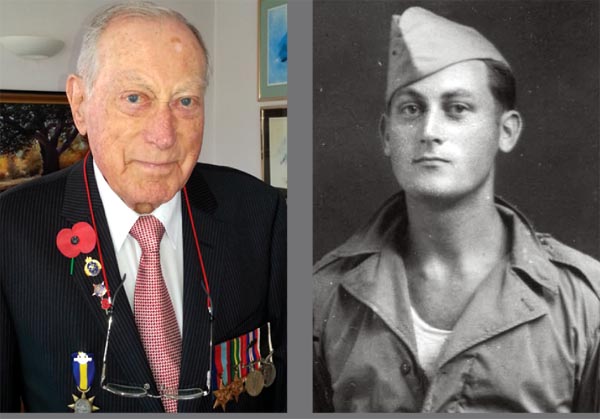

John Jones: Volunteer For the Coastwatchers

Jones was born in Northumberland, England, in 1920. His father was an American, who had served in the Royal Canadian Navy during World War I. His mother was a widow with two daughters, her first husband having been killed earlier in that war. Some years after World War I, the family emigrated from England, where his parents met and married, to New Zealand, where John’s father had been offered a job on the west coast of South Island, a part of New Zealand that was sparsely populated then and still is today. Jones lived there until he was 18 and worked for the Post and Telegraph Department as a telegraphist. At the beginning of World War II, he was asked to go to Christchurch for further training, an offer he accepted. From there he went to Wellington for additional training in radio work. At this time, the war was confined to Europe. The bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese and the resulting spread of the war to Pacific waters had not yet occurred.

In early 1941, while attending radio school John volunteered with a number of others to go to offshore islands as a coastwatcher. However, since he was not 21 he had to get parental consent. At the time, manning a radio on a Pacific Island seemed ideal compared to the possibility of later being drafted into the military and put in harm’s way. His parents agreed and gave permission. However, as Jones states in his oral history, if his parents had known that Japan would soon enter the war they probably would not have consented.

The original idea at the time was to keep an eye out for German raiders, armed merchant cruisers that had caused some destruction in Pacific waters early in the war, specifically at Nauru Island and Ocean Island, which were being mined for phosphate at the time.

A Coastwatcher’s Story in His Own Words

John Jones recently recounted his experiences as coastwatcher during discussions with the authors. He recalled:

We left New Zealand on the Matua (Union Steamship Co.). It ran regularly up to Fiji, Tonga, and other locations. We were put on that to Suva (Fiji). It was evident then that we were going to be in the tropics, which was good—better than down in the sub-Antarctic.

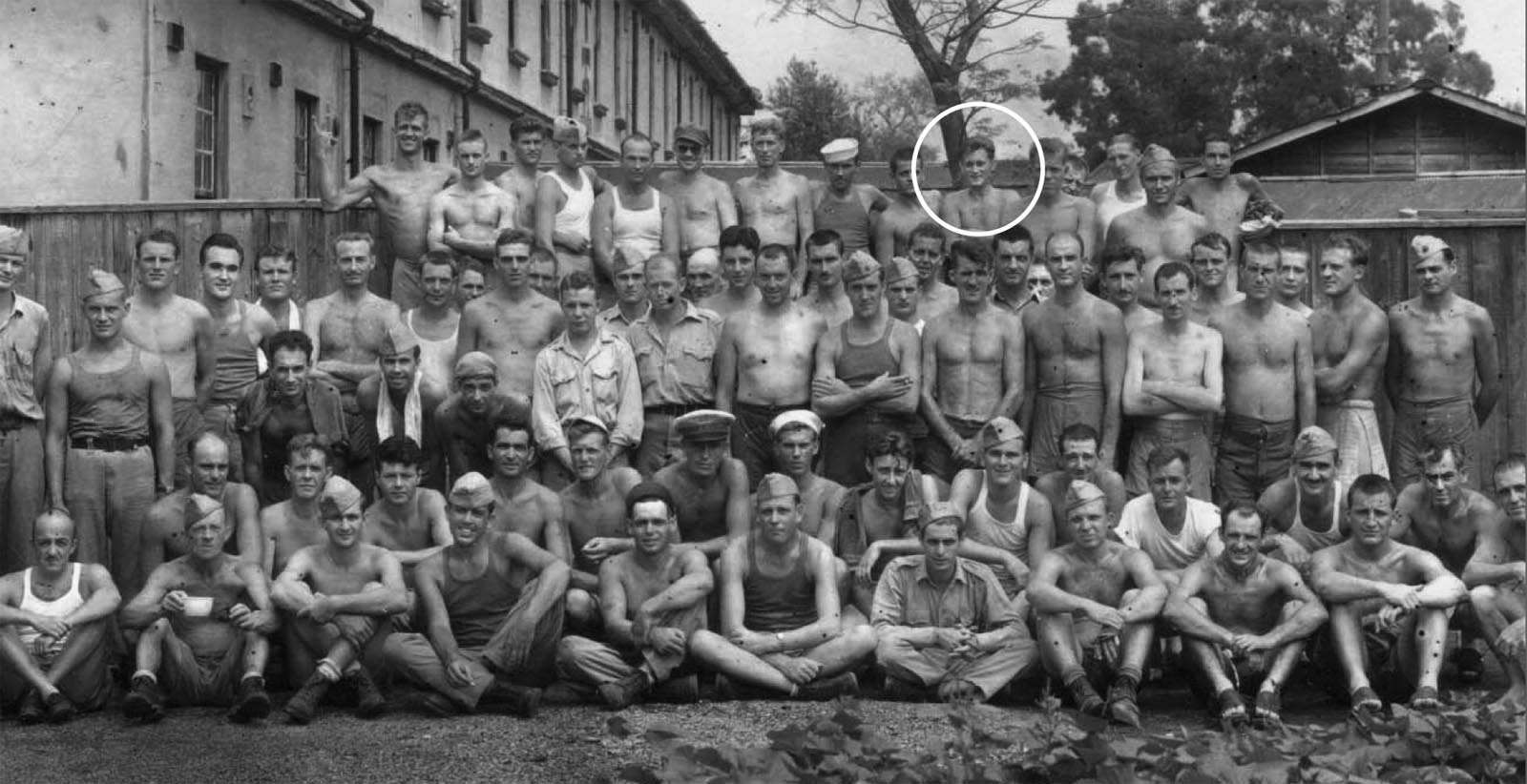

Having arrived in Fiji, we were taken out to Samabula camp, which was the headquarters for the New Zealand Overseas Expeditionary Force in that part of the world. I don’t remember how many men were there actually, but there weren’t very many—but we only spent about five days there receiving more instructions. We had code to learn, and a separate cipher code for weather reporting.

After those five days, we were told we would be leaving by ship the next day and had to be ready to leave by late morning. The ship was the governor’s yacht, Viti, which was about 900 tons—brand new. It had been launched just the year before.

We were told to buy things for our own benefit. If you smoked, and everybody did in those days, take enough cigarettes for about 12 months. We also needed sand shoes, pith helmets, and a white suit, of all things. I had a white suit and never ever wore it. It was crazy taking a white suit where we were.

The Two Japanese Officers on Butaritari

We were put aboard the Viti late the next morning. We had been warned that army [New Zealand Army personnel] would be coming with us. When we got out into the lagoon I was introduced to two unarmed soldiers (Privates J.M. Menzies and M. Menzies, who were brothers). The idea was that they were to keep me company. We were going to islands that had no Europeans or were otherwise completely uninhabited.

We were then shown a large map of the Pacific, specifically the Gilbert and Ellice Islands that ran in a northwesterly-southeasterly direction and were just south of the heavily fortified Marshall Islands that were Japanese. They were in a direct line [north] from Fiji, and of course below Fiji was New Zealand.

I am jumping ahead in years, but after the war I found out the real reason—and at the time we were never informed of the real reason—for our being sent to these islands, and that was that the [New Zealand] government had been warned by American intelligence and British intelligence that the Japanese were rattling the saber and getting very aggressive. And when you come to think about it, we were made to be human tripwires. That is what I have always called us, anyway. The most northern island in the Gilberts [Butaritari] was just 120 miles south of the big Japanese naval base of Jaluit [in the Marshall Islands].

On Butaritari, where I was, there were two Japanese (Chosito Kanzaki and another named Suzuki) who had a 45-foot ketch, and they sailed up to Jaluit not infrequently to carry copra. As we later found out, they were naval reserve officers, although they had married native women. This appeared to be Japanese strategy over the years, spreading people out to places they were interested in. One of the two appeared to be the headman, Kanzaki. That was before Pearl Harbor, so they didn’t mean anything to me.

First Japanese Fly-Over

The North Gilberts were made up of three islets. McQuinn [another coastwatcher, Corporal S.R. McQuinn] was 25 miles away on Makin, which was to the east. South of me by about 100 miles, but closer to Tarawa, was Abaiang with one New Zealander [Corporal S. R. Wallace]. There were a lot of Catholic priests and nuns there too.

Butaritari lagoon was a big lagoon, and the Japanese had eyes on it, I suppose, as a base. We were set up on a tiny islet [Bikati] at the northern part of the lagoon, where there were only about 25 people living in a small village. The main island was 14 miles south.

Before the Japanese hit Pearl Harbor, about mid-November they started to fly over us with their four-engine Kawanishi flying boat, which was a copy of the Pan Am Clippers. I saw them at about 5,000 feet and immediately went inside and coded a message when they were still in sight. I was transmitting the information, “Japanese flying boat overhead and heading due south.”

That was the first time it happened, and I didn’t realize until later that they had come down and flown around all the islands in the Gilberts and back to Jaluit. They did that three times between then and Pearl Harbor, and in late November one of the native boys came—it was about 11 o’clock at night—and said, “Lot’s of lights off the West—off the reef.”

I looked, and there was quite a decent size ship. It was lit up stem to stern, going slowly past.

I quickly coded a message and got it off early the next morning, about 0630; and I received a reply back, “Very possibly the Yamaguchi Maru, from Jaluit.”

How they knew the name, I’ll never know, but by this time, with all the planes flying over, and then this ship, it made me pretty uneasy. I thought, “If anything happens with the Japanese, well we are right on their doorstep.”

“Japanese Landing Now. Goodbye all.”

Sure enough, I woke up one morning and it was the 8th of December—the 7th in Hawaii. I sat down to send my first communication, which was at 0630, but first I tuned into Honolulu as I always did to hear the news, but they weren’t there.

I thought, “That’s funny.” I could hear noise but nothing being transmitted. So then I tuned into L.A. [Los Angeles] and got a man who was yelling his head off about Hawaii being attacked. So, that is how I got the story of the attack on Honolulu—on Pearl Harbor.

I immediately said to my two companions, “This is really bad news! The Japanese are at war with us.” And sure enough, I got a message to be double alert. Of course, we were already double alert, and all the rest of that day we were worried as to what was going to happen. We went to bed that night but didn’t sleep very much.

The next morning, before dawn, one of the lads said he thought he saw something on the western horizon. We waited until there was a bit of daylight, and sure enough the superstructures of ships—quite a number of them—could be seen, but we weren’t given binoculars. That was a sore point with us.

All that day, the 9th, they stayed there—never moved—but the next morning, the 10th, they made a three-point landing on the main island. That was 14 miles down from us.

A native operator south in the lagoon was trying to contact Ocean Island, which was our parent station, and he wasn’t getting a reply, so I cut in in plain English and told him I would pass it on. So I coded it and told him I would pass it on as soon as I could. Then he told me in plain English, “They’ll be up to get you next.”

We [John Jones and the Menzies brothers] sat there all that day and the next day, but nothing happened; but on the 12th one of the boys rushed in and said that something was approaching on the outside of the reef.

When we looked we could see a launch, and by the look of it, it was towing a couple of whaleboats. As they got closer, we could see that each one held a certain number of troops. Incidentally, as it turned out they were all [Japanese] marines. I immediately started transmitting, and as I was transmitting a single-engine floatplane came over, and of course he told the approaching launch exactly where to land.

In the meantime, I burned all the codes, smashed all my equipment, and made myself ready to receive them. My last message was, “Japanese landing now. Goodbye all.”

Captured and Interrogated

While we were waiting for them, the previous day we had taken all of our stores and gone into the thick undergrowth and dug a big pit. Most of it was tinned stuff, and we covered it over. The reason we did this was because I figured that we could have been left there isolated.

I might add that in later years we were mighty pleased to learn that the Navy had captured us, and not the Army. Anyway, they put a ring of marines around us with fixed bayonets. We had to sit back-to-back out back of our house. There was a [Japanese] lieutenant who tried to speak English. He wasn’t very good at it, but what we got out of him was that Japan was all victorious and in charge of the whole Pacific, and that we should behave ourselves.

In the meantime, they had brought all 25 people from the village to come and watch us, and then the lieutenant came over and asked if I was the wireless operator. He said why did you burn your codes and smash your radio? That is very wrong! He made out that he was very upset, which I suppose he was. And these marines were very graphic in what was going to happen to us. They kept saying we would be beheaded, and this went on for three hours, at least, while we were sitting in the sand.

Eventually, they said we were going to be moved down on the beach.

We thought, “Oh well; it’s going to happen there.”

I was prepared that it was the end, but when we got there we were surprised to be loaded up and taken to the main islet—Butaritari. There were ships there and four Kawanishi flying boats. You see, what had happened, these flying boats had flown over us, and each time they flew over an island our coastwatchers started transmitting. They picked up the transmissions and pinpointed where all the coastwatchers were.

They took me up to the captain’s cabin on one of the ships, and the captain spoke very good English. It was a heavy cruiser, but I don’t remember the name of it. He pulled out a map of the Gilbert Islands. It was written in Japanese and English, and he said in English, “Point out where your friends are.”

Then he asked, “You did report my ships?” I said, “Yes.” He said, “We thought so.” Then he said, “How did you get here? You came from Fiji, didn’t you? I want to know where the airfields are. Here is a map of Fiji. Where are the airfields?” I said, “I didn’t come from Fiji.” Of course, I did, and I was running a bit of a risk, but said, “No, I came from Australia.”

“Ah,” he said, “you Australia. How you get here then?’

“Via Nauru and Ocean Island,” I said. Then he asked me where these people are [other coastwatchers]. I said I didn’t know, and he said, “Okay, you go with your two companions and you will be put into confinement here.”

Christmas in Captivity

We were made to stand in the hot sun for the rest of the day, and then about 6 o’clock or 7 o’clock that evening we were moved onto On Chong’s Wharf [named for a Chinese trading company]. On the end of the wharf was a house. We were put in a room in the house, and lo and behold we found that Williams, the resident commissioner, was in the next room. We talked, but that only lasted about a half hour because they came in and said, “No talk,” and slapped us.

The next day, McQuinn and his two New Zealand soldiers [Privates L.B.H. Muller and B.L. Were] were brought in. They were captured about 1 o’clock in the morning. That made seven of us. There was one priest on Butaritari, where Williams lived. His name was [Father Pierre] Guichard. He wasn’t touched; he said he was Swiss, so he was neutral. But all the priests, I found out later, said they were Swiss or Vichy French.

We had Christmas Day, but they didn’t give us anything special; but Williams had been very good to the Japanese prior to Pearl Harbor. He talked to them nicely and made friends with them, and Kanzaki had been made head interpreter. On Christmas Day, Kanzaki turned up and said, “Two bottles of wine, Williams, for your Christmas.” Williams said, “Oh, thank you very much.” Kanzaki said, “Oh, don’t thank me; I took it from your stores.”

That sort of made our Christmas Day, anyway.

Leaving the Gilbert Islands

On the 27th, we were ordered out and told we were going on a ship. We had to put our stuff on a cart. Williams had to pull, while the rest of us pushed. We had to travel about half a mile through the village, and all the villagers and all the Japanese were lined up. They yelled and jeered and carried on as we went past. This was to let the local population know that they were in charge by belittling Williams in front of them. Father Guichard was watching as well.

We got out to the ship and just brushed alongside and were told to go back. We went back to On Chong’s Wharf, and two days later away we went. It was a minelayer we were on. We were taken down below and there were little railway lines with carts on them for dropping the mines off the back.

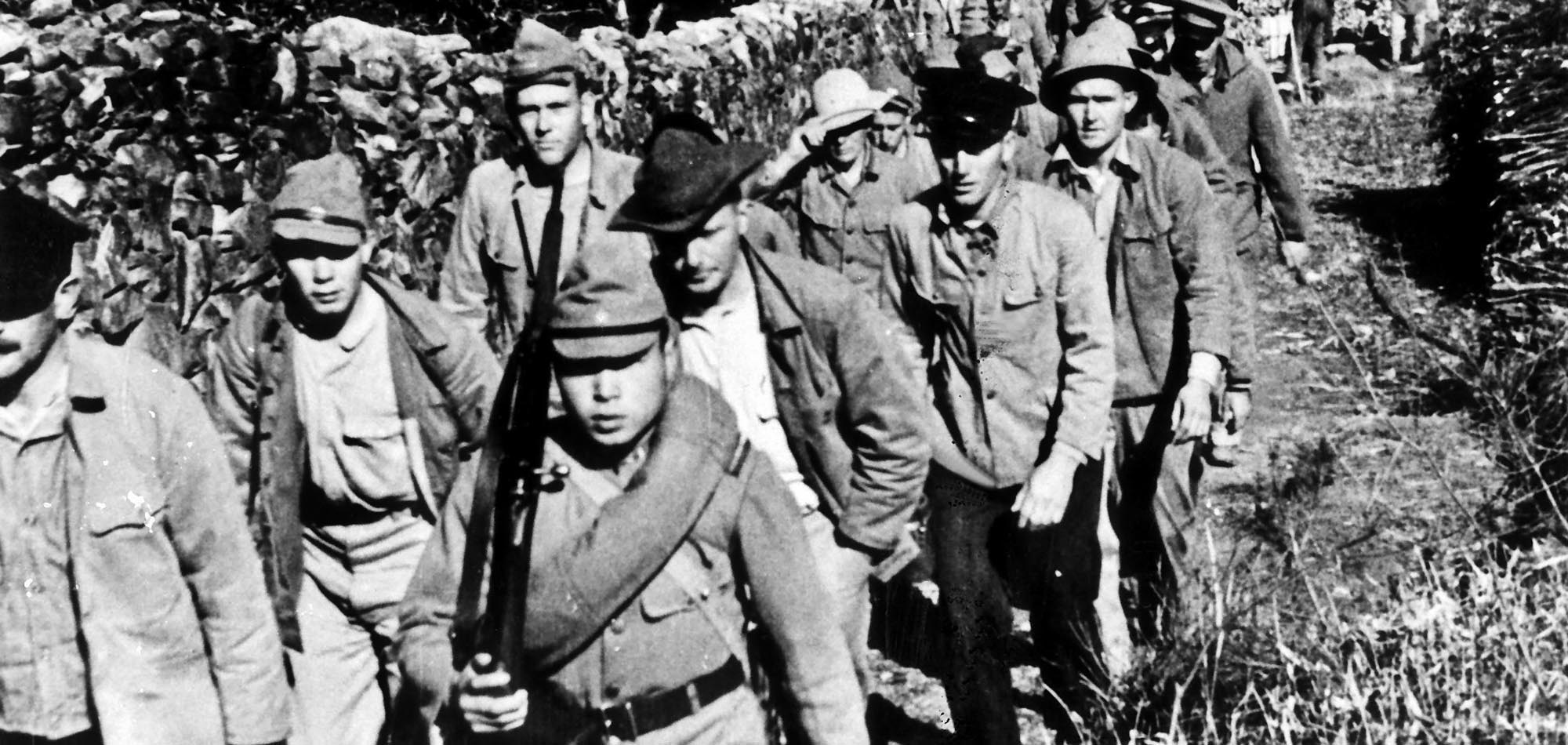

We were given rice and a pickle for a meal that night. The next morning, we were already in a lagoon, Jaluit, the big naval base just up the road. From there, we were taken to another boat, which was a small gunboat. It had a coal-fed engine, and there sitting on the coal was Wallace, who had been caught on the 24th on Abaiang. That cleaned out the northern group. They had collected all eight of us.

Wallace was very pleased to see us, of course. The engines started and away we went, and we ended up on Kwajalein in the very north of the Marshall Islands. It is probably one of the biggest lagoons in the Pacific. We were transferred there to the Yamagiri Maru, which was about 7,000 tons. It was a cargo-passenger ship. But I was surprised at what I saw in that lagoon. I counted 10 submarines. That is all I had time for before they whipped us down below; but there were all types of ships in there.

Once we got aboard, we were taken down between decks, and we were amazed to see 200 to 300 coolie-types; quite a number of them appeared to be Koreans. They were an inquisitive lot; they came right over to us and peered at us, so the officers on the ship put canvas around us, which was nice of them.

The ship left almost immediately. We were then offered American Wonder Bread, with the polka dots all over the wrapper. We were never able to figure out which way we were going, although we figured we were heading due west through the Caroline Islands. And the way they were starting and stopping, we thought they were trying to avoid torpedoes, and we thought that if we got torpedoed we would never get out.

Housed in a European Enclave

The 7th of January, 1942, we arrived at Yokosuka Naval Base. We were in sight of Mt. Fuji, and it was a grand sight, I must admit, but we were in tropical gear and it was below zero. We were then shifted by launch to Yokohama, and by truck we were taken to the Yokohama Race Course, where the toilets, etc., were all European. We were fed there—rice and the usual stuff—and the next morning our group, the eight of us, were taken by truck once again to 250 The Bluff, Yokohama. That was in the European enclave right in the middle of Yokohama. Here was a two-story house, a very nice looking place, set in a beautiful garden. We were taken inside. It was nicely furnished, and there was a library that was sealed off. Over the next couple of days, we undid the seals and found all these beautiful books, so we stole quite a number of them. Also, while we were there, we found a card. The people who had been there were Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Dillinghearse Denison of Standard Oil.

There was a dining room there, and we were told to sit down for lunch. Lo and behold, we were waited on by two kimono-clad Japanese girls, and we were offered European food. We didn’t know what the meat was, but the bones looked like dog bones. However, whatever it was it was mighty good.

We were fed there for a week, and we were photographed there every day being fed and waited on and being escorted around our beautiful garden. The photographers were here, there, and everywhere. Then after about six days, we were shown the Tokyo Mainichi Shinbun newspaper, and there was our photograph on the front page. It said that we were Australians captured in the islands and that we had been treated very well. I found out later that these photographs had turned up in Argentina and also the United States.

Oshiro Asabuki: The Friendly Interpreter

We were then taken by train from Yokohama overnight to the island of Shikoku, and we ended up in the garrison town of Zentsuji. We opened up the first prison camp there, the eight of us [actually nine as they had been joined by Arthur Griffiths, a radio operator from the U.S. embassy in Tsingtao, China]. We arrived at 1:30 in the afternoon after traveling all night. There were barracks, two-storied, with raised platforms on each side, with space in the middle for a table and benches. We were given a meal at around 5 o’clock of rice and pickles. We were told that 9 o’clock would be lights out.

The guards were walking in and out all the time, and that was the norm. We dropped off to sleep that first night, and at about midnight we were awakened by a hell of a noise. It was heavy boots on the wooden floor, and it was 450 men from Guam. There were about 100 civilians with them, including five Navy nurses and the governor of Guam, [Captain] McMillan.

In the morning the guards came in and woke us up. We had to stand up and be counted. We milled around for all of January and part of February, and then we were told by Warrant Officer Lane, he was from Guam, what we would have to do. The Japanese would tell Lane, and he would tell us. He didn’t speak Japanese.

We had three interpreters, but the chief interpreter was Oshiro Asabuki. He was educated at Oxford and the Sorbonne, and in his own right he was a duke. Williams, our resident commissioner in the Gilbert Islands, was still with us, and he got quite friendly with Asabuki because Williams was also educated at Oxford. A short time later, Asabuki got Williams transferred to the officers’ quarters.

David Hutchinson Smith, a captain in the Australian Army who was captured at Rabaul, went back to Japan to find and meet with Asabuki; it was probably in the early 1980s. He told us all about it at a reunion we had in the States. I didn’t get to the first one, but I got to the second one in L.A.

There were two other interpreters, but I can’t tell you their names [Tajima and Moryama]; they weren’t very friendly. They were fairly short and wore large Army boots halfway up their legs, and they had a habit if they slapped you—if they couldn’t reach you because some of the Aussies were over six feet tall—they kicked you in the shins. Our shins took quite a beating; they were always bleeding. These interpreters did this quite often, but never did Asabuki touch anyone. He never hit anyone.

A Radio Message Home

After about four months, the camp had about 700 officers and 100 enlisted men. There had been 250 enlisted men, but about half of them had been transferred to Osaka and Kobe. That left 110 enlisted men at Zentsuji. We three radio operators and the New Zealand Army troops that accompanied us were sold to a company that constructed terraced rice paddies. They took us in squads up to nearby Osayama Mountain, where we cleared land and built retaining walls and terraced it for rice growing. It was very steep.

We were still at that when around August-September [1942?] most of us were sold to a stevedore company. They paid us what would come to about a penny and a half a day. About once a month they gave us some yen but said half of it was being kept for us for a rainy day.

We found out later that the New Zealand government had told our families that we were missing in action. They didn’t know where we were. Later in Japan we broadcast from JOA Tokyo to Australia and New Zealand. We had little messages typed for us, and all they said was, “To Mr. and Mrs. Jones, my address, I am well. We are being fed okay.” Nothing except that. It was about 25 words.

Funny enough, the neighbors heard me broadcasting that night. They rushed next door and said to my parents, “Did you hear Tokyo?”

They said, “No.”

“John was on!”

That was very upsetting for them, but it was said that it would be broadcast again, so they tuned in again the next evening and sure enough they heard my broadcast. They were relieved, but not altogether, because with the Japanese it was very dicey whether you lived or died. But if you made it to Japan you had a 50-50 chance.

Red Cross in the Camps

Zentsuji was the only camp that I know of where the Red Cross was permitted to visit us, and it had to be a bit better than all the other camps. The reason was because those five nurses from Guam and a fellow by the name of Griffiths had joined us in Yokohama. He was a radio operator for the U.S. Navy, but he had been seconded to the embassy in Tsingtao, China, and he was captured there. He was brought to Japan and put with us. He was treated as a prisoner of war, but the American ambassador in Tokyo said, “No, no, no; he is part and parcel of our entourage, so he is classed as a diplomat and will be exchanged for Japanese diplomats.” So, he left us and took all of our little messages back to the States. That was the second message that my parents got. They got that later within the year from Griffiths. I don’t remember his full name.

The four Navy nurses from Guam were given a room meant for two people. This sort of accommodation was given to anybody who was somebody. For instance, the [British] cruiser Exeter was sunk in the Battle of Sunda Strait. We had her officers at our place, and Captain [Oliver] Gordon, the English captain, was given a room, I think, with a major or a colonel from the U.S. Marines, I think from Guam.

I’m getting on a bit, but this is getting on to the end of 1942 when this happened. But those nurses, with Griffiths, were sent to Tokyo about June or July 1942. So, they had been in the prison camp for about five months. They knew exactly where it was and how we were being treated. Because of all this the word got out that we would be treated just a little bit above normal. Well, as it turned out, we were a hell of a lot better than normal, because when Captain Gordon was put in this other prison camp somewhere near Tokyo they beat the hell out of him. He was really badly treated, and so were the majority of prisoners [in other camps].

We got slapped around and shins kicked, and so on and so on, but we were also starving. We didn’t have enough food. It wasn’t so bad to begin with, I must admit, but then it deteriorated. In 1944, I passed out one day while trying to carry a tin of what was supposed to be soup. It was just colored water.

I also hurt my back building these rice terraces. I had a yoyo pole with two baskets. There were too many rocks in it. I got up, took two or three steps, slipped on a rock, and my back went click! They carried me down the hill and back to the camp. I was about two or three weeks, I can’t remember now, lying on boards, which was good for my back anyway.

It was about 18 months after the nurses got back to the States, and a Swiss [Red Cross] representative from Tokyo came, and it was all a setup. There was a table loaded with socks and little pieces of meat, and each man had to go up and bow and take a pair of socks and a little piece of meat in front of the Swiss. He was married to a Japanese and had been in Japan for 20-odd years. He was more Japanese than he was Swiss. We never saw him again. However, this information got back to the States, and we were noted for being a bit better off than other people, but it couldn’t be said that we were going to live.

The Fate of the Coastwatchers at Tarawa

We didn’t have any information on what happened to the other coastwatchers in the Gilbert Islands. We [in the northern Gilberts] were taken right away and were very lucky. The Japanese went to Tarawa and told the Europeans there that they had taken the islands. They looted the place and smashed all the boats and told the Europeans not to move. “We’ll be back.”

They left them there and went up to Butaritari, where they intended to put in a seaplane base. The New Zealand government, between December 1941 and September 1942, had nine months in which to take our guys out, and they didn’t. They could have gotten them out, and furthermore they asked each one, “Do you want to be replaced?”

None of them wanted to be replaced.

They [the New Zealand government] must have said that tongue-in-cheek because they didn’t have the radio operators to replace them with. Furthermore, they had native operators quite capable of taking over. The [Japanese] Navy picked them up, and they turned them over to the [Japanese] Army, and the Army only had them two weeks and executed the lot. They beheaded the lot, and the beheading was seen by a native.

We didn’t know anything about what happened to our fellows while we were in the camp, but one day I was on a work party and one of the fellows said to me, “Hey, did you see that fellow who came in yesterday?” I said, “What fellow?”

“Oh,” he said, “it was an American pilot [Lieutenant Fred Francis Garrett, 30th Bomb Group, 17th Bomb Squadron, flying the Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber Our Baby, shot down on December 15, 1943].”

He said he was on crutches; he had a leg cut off. I said, “Where did he come from?”

The next day was a day off for me, so I went and found him and said, “I understand you were shot down in mid-Pacific somewhere.”

He said, “Yeah, that’s right; I was shot down in the Marshall Islands.”

I said, “That is where we were captured, just south of there; but we were taken to the Marshall Islands.” Then I asked him, “Where did you take off from?”

He said, “We took off from Tarawa.”

I said, “While you were in the Gilbert Islands, did you know any of our fellows. We had a unit there called the Coastwatcher Unit. They were all from Tarawa, south.”

He said, “Yeah, yeah; I never met them, but there is a monument there that our guys put up in memory of all 22. They were all beheaded.”

I just broke out in a sweat. I said, “Well, they were all people I knew. My three best friends were amongst them.” So, I went and told the other guys. We were amazed that they had been beheaded, but then the atrocity stories were coming in all the time.

After the war I said to myself, “I’m going to meet their families.”

I went to see the mother of my good friend, Rex Hearn, living in Hastings. She received me, but it upset her. She was trembling and crying; and she showed me Rex’s bedroom the way he had left it. She said, “I never touched anything.”

I was so upset with the way she was upset that, as I was on the way down south to visit the family of Arthur Heenan in Middlemarch, and also Cliff Pearsall’s, I decided against it. Pearsall was from central Otago. I couldn’t go any farther because I broke down too.

“We Were Lucky”

It went on and on and on. We opened that camp up, and we had been prisoners three years and nine months. Of course, it was marvelous to see the B-29s flying over. The earth just shook when they bombed Kobe and Osaka, which was just down the road. We were 70 miles away from Hiroshima. When that dropped [the Atomic bomb], a little Japanese told us one bomb had killed a quarter of a million people.

Then when fighter planes came over, Corsairs, they would come down and shoot the hell out of the place and we would have to dive under the boxcars. We were unloading sugar this one particular time and had just enough time to see two Corsairs coming toward us between two small hills, and we got under these flatcars. None of us got killed, but we were very lucky because they wouldn’t let us go on passenger cars on trains, and one of the delights of the Corsairs was to see a train and strafe it. Yeah, we were lucky, very lucky!

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments