By John Domagalski

The bleak opening days of World War II in the Pacific found the American territory of the Philippines under attack from the Japanese. American and Filipino army forces under the command of General Douglas MacArthur quickly withdrew into the Bataan Peninsula off Manila Bay and the adjacent fortified island of Corregidor. Here they would hold back the invading enemy as long as possible—either until reinforcements arrived or until a last stand.

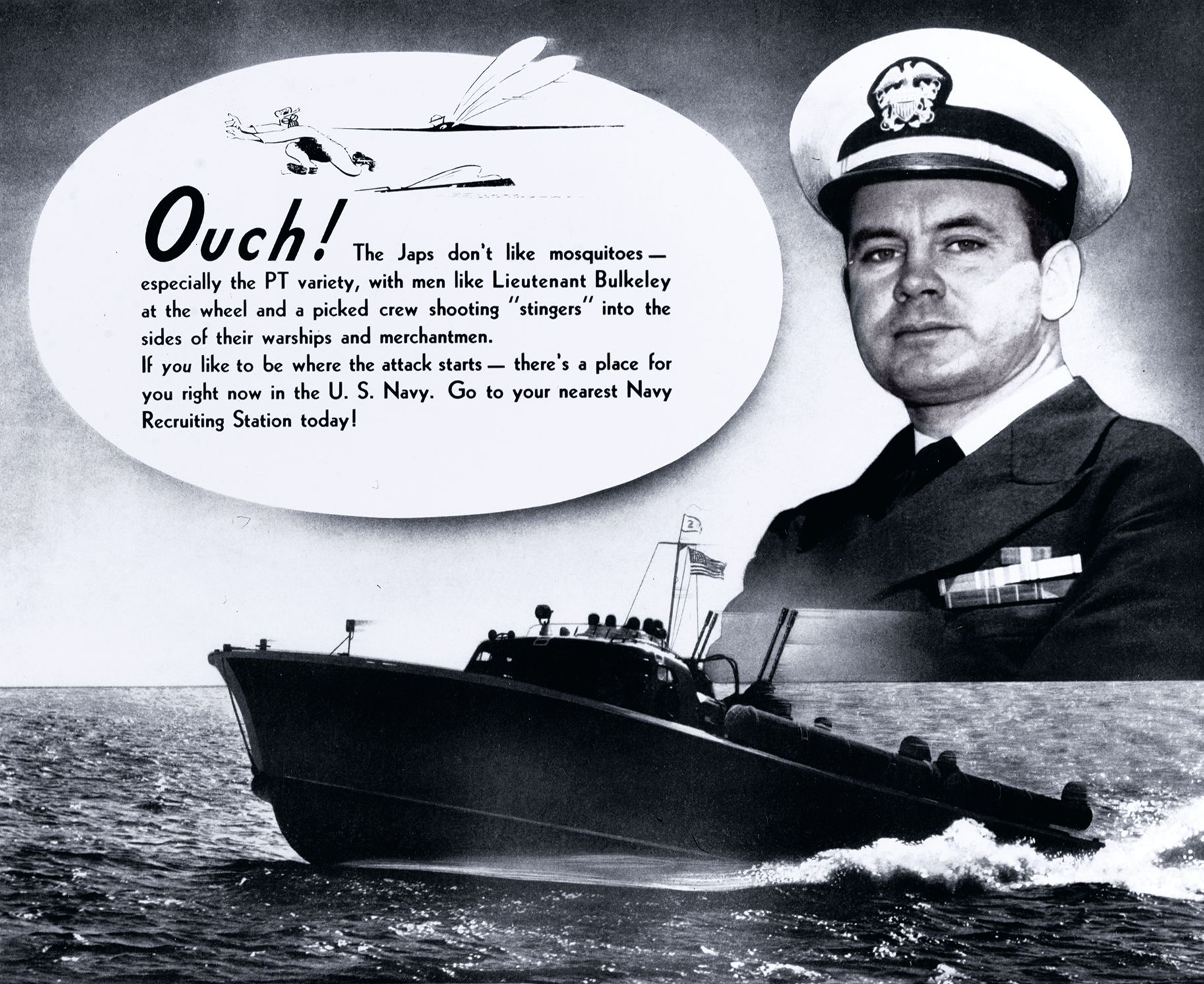

Most of the large American warships stationed in the Philippines quickly retreated south to safer waters in the Netherlands East Indies. Among the assorted small craft left behind were the six torpedo boats of Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron Three under the command of Lieutenant John Bulkeley. The patrol torpedo or PT-boats were among the newest and smallest warships in the U.S. Navy—and were untested in battle.

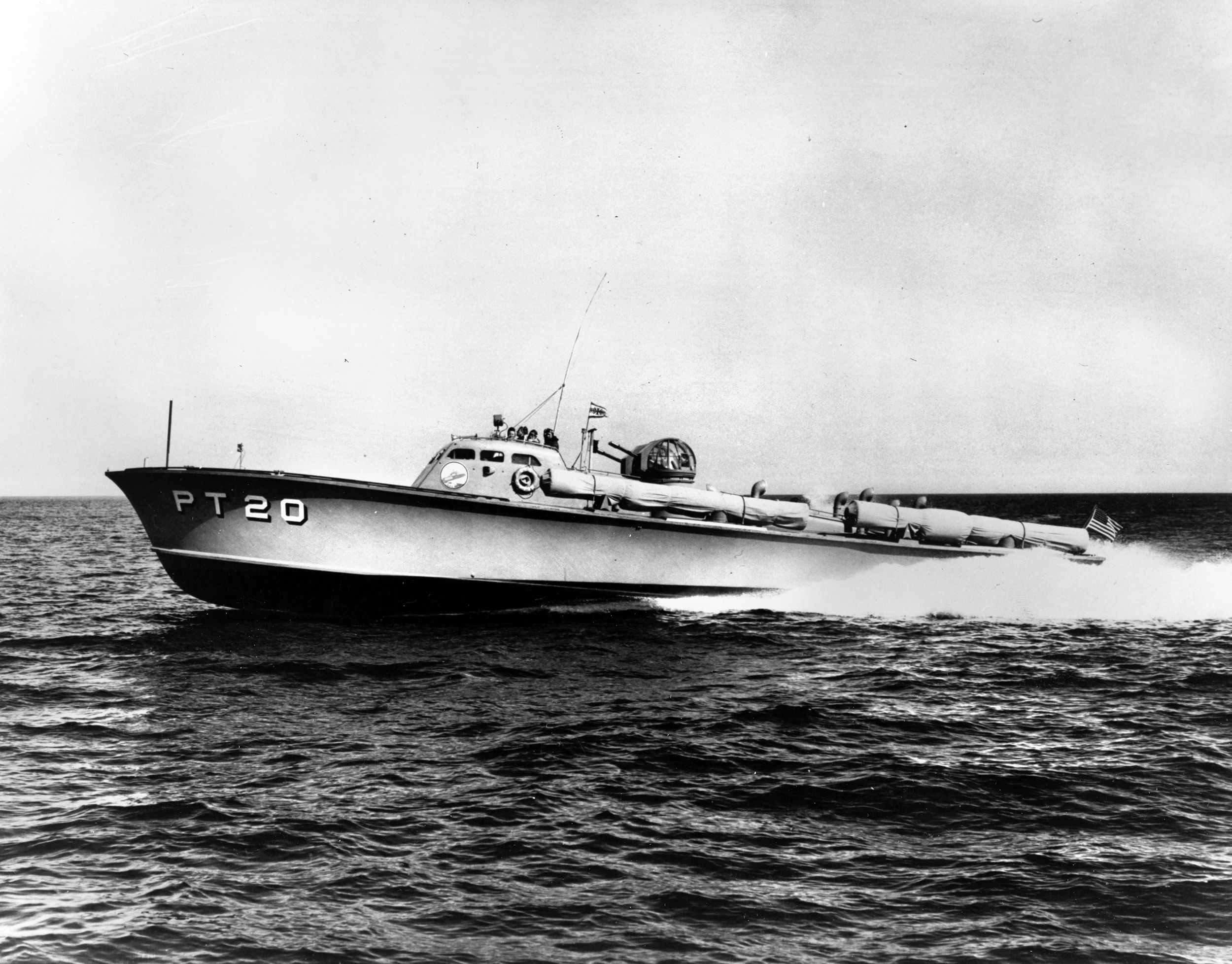

Built by the Electric Boat Company in Bayonne, New Jersey, each of Bulkeley’s PT-boats measured 77 feet in length, displaced 40 tons, and were constructed of wood. Three supercharged engines turned a like number of screws allowing for speeds up to 40 knots. Armament consisted of four 21-inch torpedoes and a small assortment of machine guns. The boats, manned by 10-15 sailors, had no armor protection as afforded on larger warships.

As the defense of the Philippines crumbled, the PT-boats battled Japanese shipping and supported ground forces. The brave sailors manning the boats had no way of knowing they were armed with faulty torpedoes—problems with the underwater weapons were not identified until later in the war. The PT-boats gained fame for the March 1942 evacuation of General MacArthur and other key officers from Corregidor to the southern Philippines, where the evacuees were then flown to Australia. The torpedo boats remained in the southern Philippines after the evacuation operation.

The squadron was down to two operational boats when John Bulkeley received a report of Japanese warships operating in the Cebu area during the late afternoon of April 8. The information appeared to be specific and actionable—Army aircraft spotted two Japanese warships on a southerly course off the west coast of Cebu at 5:20 p.m. “The estimated enemy speed was five knots,” Bulkeley recorded. “It was believed that the enemy would arrive at the strait between Cebu and Negros Islands, south point at midnight.”

The enemy vessels were in Tanon Strait. The long and narrow body of water was wedged between the two similarly slender islands of Cebu and Negros. The strait was not very wide at any point but closed to a channel of less than four miles at Tanon Point off the southern tip of Cebu and Negros before emptying into the larger Mindanao Sea.

The squadron commander speculated the enemy was searching for the many small inter-island steamers known to ply the waters throughout the Philippines. After a careful study of the maps, he concluded it was a perfect setup for a night ambush. His plan was to catch the enemy ships as they passed through the Tanon narrows. Bulkeley ordered his two available boats—PT-34 and his flagship PT-41—to be ready to put to sea at 7 p.m.

Lieutenant Robert Kelly rushed to get his PT-34 ready for departure. Ensign Iliff Richardson was serving as his executive officer. Two sailors from the idle PT-35 were pressed into service to cover for others on shore leave. “I hope this isn’t another wild goose chase,” Kelly remarked as the boats pulled out of Cebu City at dusk with Bulkeley’s PT-41 in the lead.

“Weather conditions were ideal,” Kelly reported. “It was a dark night with no wind and calm seas. Moonrise was about 2 a.m.” The boats were off the east coast of Cebu traveling south. “The night was clear and the outlines of the island peaks and valleys could be seen in silhouette against the starlit sky,” Richardson wrote. Kelly sent him below for some rest. “As I went below, I was particularly pleased with the sound of the grinding whine of the engines and vibration-less shafts and propellers.” Richardson quickly fell asleep.

The PTs arrived off Tanon Point at about 11:30 p.m. “The boats lay-to with engines idling about 1,000 yards apart roughly in a left formation,” Kelly wrote. Partially obscured by Cebu Island, they waited patiently for the enemy ships to be spotted.

“The plan of attack, if there were only one target, was for the PT-41 to lead the attack from the target’s port beam,” Kelly recalled of the operational plan. “The PT-34 was to follow, attacking from the port bow. If two targets were seen to emerge from Tanon Strait, then each boat would attack separate targets with the PT-41 leading the attack.” They maintained radio silence, not wanting to risk discovery by the Japanese.

Sailors aboard the boats carefully scanned the horizon for any sign of movement. A lookout aboard PT-41 was the first to spot the enemy. “There she is,” he shouted “Jumping Jesus! There she is!” The Japanese light cruiser Kuma slowly emerged from the darkness. The ambush was playing out almost exactly as Bulkeley had planned.

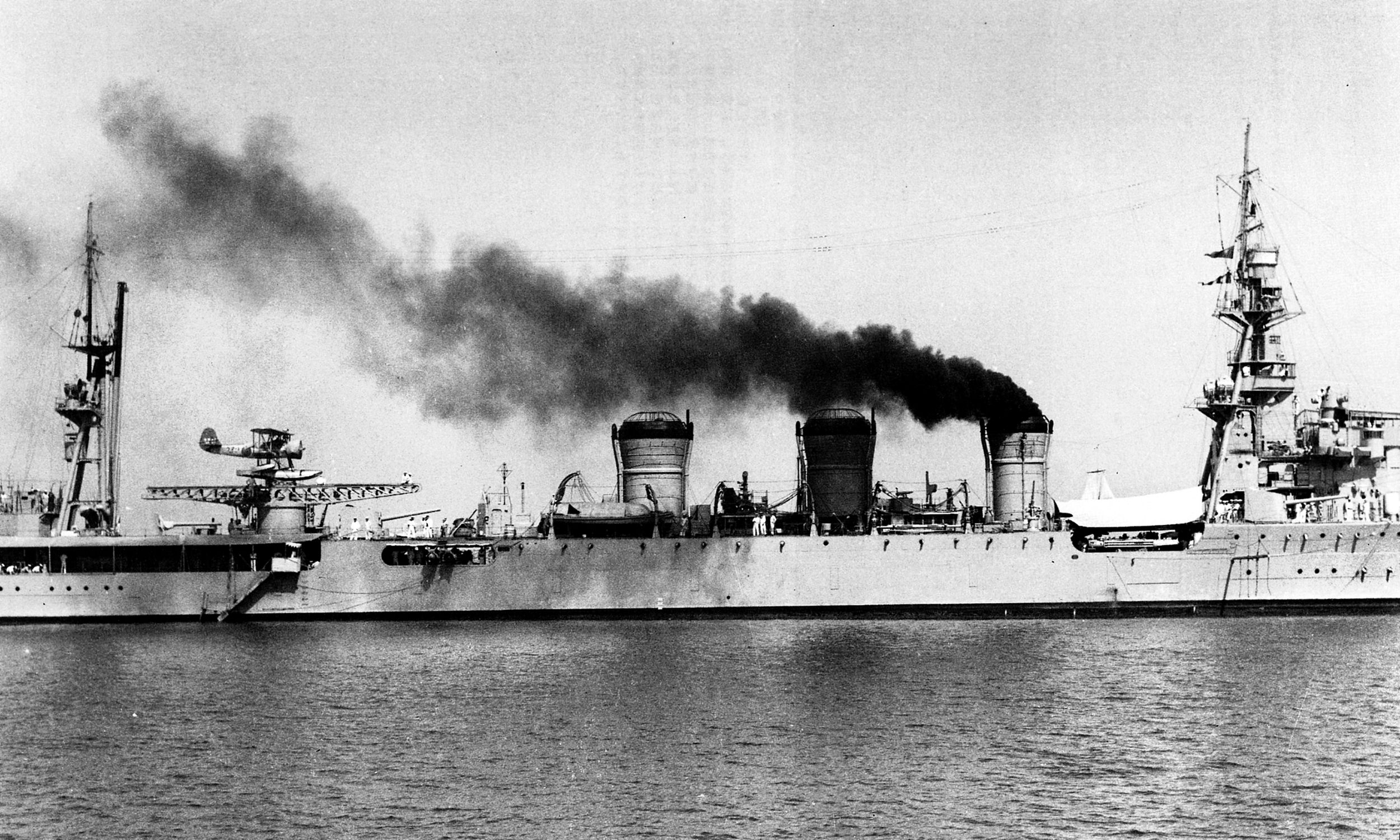

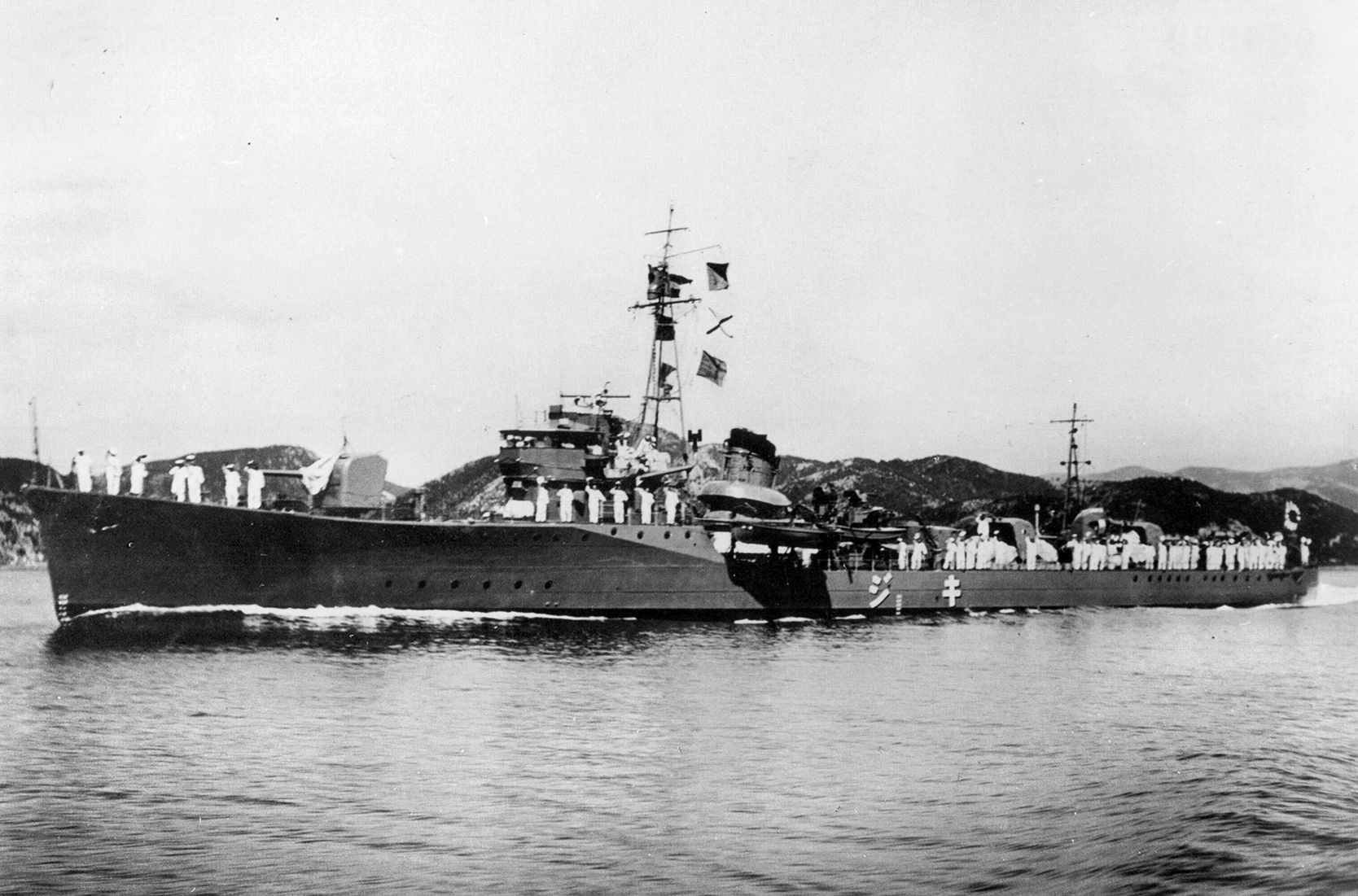

The Japanese warship was the largest ever confronted to date by the small PT boats. She stretched a length of 535 feet and weighed 5,870 tons. The Kuma was armed with seven 5.5-inch main battery cannons—each capable of blowing a small PT boat to pieces—and an assortment of smaller guns. Japanese sources report the torpedo boat Kiji was operating with Kuma on the evening of April 8. Not similar to the small American PT-boats, the Kiji was almost 300 feet in length armed with three 4.7-inch guns and one smaller antiaircraft cannon.

At first, the American sailors only saw the light cruiser. “No other vessels could be seen at the time although her escorts must have either been obscured by the Negros coastline or been following some distance astern,” Kelly wrote. He called the crew to general quarters.

Iliff Richardson abruptly awoke from sleep and raced to his battle station. He arrived at his assigned station—the boat’s wheel—and spotted the enemy. “The cruiser loomed bigger and bigger in the semi-darkness as we continued on,” he wrote.

The attack began with PT-41 approaching the port side of the target. She unleashed two torpedoes from about 500 yards. Both of the underwater missiles missed the cruiser after running erratically. PT-41 increased speed while turning to the right in preparation to fire her two remaining torpedoes.

While PT-41 was making her torpedo run, PT-34 approached off the cruiser’s bow. The machine guns on Kelly’s boat were ready for action. The two single .30-caliber guns on the forward deck were manned by Chief Machinist’s Mate Velt Hunter and Quartermaster First Class Albert Ross. The more powerful dual .50-caliber machine guns were manned by Chief Commissary Steward Willard Reynolds and Torpedoman’s Mate Second Class David Harris. An additional sailor was stationed below deck ready to pass up extra boxes of .50-caliber ammunition.

Both officers were positioned in the small bridge area known as the conn. Kelly was intently watching the target through the torpedo director while Richardson manned the nearby wheel. “Steering was easy and my job was simply to line up the forward radio antenna mast with the metal brace supporting the windshield and alter course as necessary to keep these lined up with the cruiser’s mid-section,” Richardson later wrote. “All was silent aboard, except the noise of the exhaust and an occasional terse command from Mr. Kelly.”

PT-34 unleashed two torpedoes on Kelly’s order at a distance of 500 yards. The depth settings were set to run at six feet. “The cruiser appeared to come to life at about that same instance and was seen to be increasing its speed rapidly,” Kelly reported. A searchlight on the Japanese ship suddenly snapped on. Richardson recalled it looked “like a lighthouse beacon, dazzlingly brilliant on eyes already accustomed to the darkness.”

Located on the after part of Kuma, the searchlight briefly swept the sky before stopping on PT-34. “Apparently the engines of the PTs (there were no mufflers on PTs at that time) plus the powder flash from the torpedo impulse charges had aroused the cruiser,” Kelly wrote. “The two torpedoes of the PT-34 passed considerably astern due to the cruiser’s unexpected increase in speed.”

As the war progressed, becoming caught in an enemy searchlight was to become every PT sailor’s nightmare—a precursor to a deadly hail of gunfire. The Kuma opened fire, unleashing shells from her main guns and a variety of smaller automatic weapons. “The white orange flash of the five-inch gun from the cruiser was accompanied by the scream of the shell and then two explosions,” Richardson recounted of the terrifying moment. “One from the gun and the other from the exploding shell as it hit the water several hundred yards astern of the 34.” Each shell could blow the small PT boat to pieces.

Willard Reynolds opened fire on the searchlight on orders from Kelly. “Streams of our own orange tracers poured in the direction of the cruiser as I came right so that the port gun would bear on the target,” Richardson wrote. “Bursts from the twin .50-caliber machine guns cut paths in the darkness and sometimes ricocheted from the water high into the air.” The searchlight was not hit in spite of the torrent of bullets sent its way.

The boat skipper shouted a continuous stream of orders in an attempt to elude the Japanese gunfire. Richardson routinely repeated each command as he made various turns of the wheel. He briefly saw a geyser of water gush up behind the boat and could hear the clatter of enemy machine gun fire between the booms of the larger guns.

Suddenly, Richardson heard a different sound of gunfire. He assumed it was some type of rapid fire antiaircraft gun. The sound was quickly followed by an explosion almost directly overhead. He was knocked to his knees but did not seem to be hurt. Glancing around he saw the boat was still intact. Richardson jumped back up to his position at the wheel and continued following the skipper’s orders.

At the same time PT-34 was under intense fire PT-41 made an abrupt U-turn causing the sailors on PT-34 to lose sight of her. “Thereafter the movements of the PT-41 were unobserved by the PT-34 due to being almost constantly blinded by enemy searchlights for the next 10-15 minutes,” Kelly wrote.

Bulkeley knew PT-34 was in trouble. His own boat was out of torpedoes leaving only machine guns available to provide help. PT-41 passed along the starboard side of Kuma raking her with machine-gun fire to draw attention away from the other PT-boat. He wanted to deceive the enemy and “give the illusion that there were many torpedo boats in the vicinity.”

Enemy shells continued to fall all around PT-34. Kelly still had two torpedoes and decided to make another run at the Japanese cruiser. Moving back about 2,500 yards to turn around he then approached Kuma from almost dead stern. “It was estimated that the cruiser was making 20-25 knots,” he recalled. “The PT-34’s speed was now about 32 knots. Pursuit was maintained for about five or 10 minutes by which time the PT-34 was within 300 yards of the cruiser whose searchlight beam was depressed almost to the vertical in order to keep the PT-34 illuminated.”

Kelly ordered his gunners to again open fire on the searchlight once the torpedo boat moved as close as possible to the target. “Reynolds is hit, came a yell from behind, which put the port turret out of commission,” Richardson wrote of the moment. The gunner fell to the deck with grave wounds to his throat and shoulder.

Kelly now made the critical decision to fire the two torpedoes. The poor shot angle was from almost dead astern of the target—but saved the boat from likely being blown out of the water had she moved any further forward. The underwater missiles shot out toward the Kuma’s starboard quarter.

The focus of the PT sailors quickly turned to getting away. The PT turned sharply to the right and poured on all available speed in an attempt to get away to the south. Suddenly, a ship Kelly identified as a Japanese destroyer—most likely the torpedo boat Kiji—suddenly appeared about 2,000 yards away and opened fire. All the while, PT-34 was still under illumination and fire from the cruiser.

The action unfolded at a furious pace. “Hard right,” Kelly shouted out. “Rudder is hard right,” Richardson repeated as he grasped the wheel. The PT temporarily fell out of the searchlight but was soon back in its grasp. “The cruiser turned, apparently to follow us and prevent our escaping the destroyer closing us to port,” Kelly wrote. He momentarily thought his boat was trapped. “Just then two spouts of water some 20 feet high and 30 feet apart were seen by me through the binoculars to appear amidships at the cruiser’s waterline at five second intervals. My first reaction was that the cruiser had been hit by two rounds from the destroyer firing on me to starboard.”

Chief Torpedoman’s Mate John Martino was also watching the target and reported she was hit by the torpedoes after apparently turning into the path of the weapons. “All this had occurred in less than a minute after firing,” Kelly wrote. “The cruiser’s searchlight immediately began to fade as though there had been a power failure aboard. All its guns stopped firing and that was the last I ever saw of it.”

The skipper now focused on getting away from the other Japanese ship. His boat was caught in her searchlight and taking heavy fire. “As a result of having expended its torpedoes and being light on fuel, the PT-34 could now make a maximum speed of about 38 knots,” Kelly wrote.

“Moments were like years,” Richardson recalled of the tense minutes. “The increased speed of the Mighty 34 seemed a snail’s pace.” The torpedo boat was able to slip away from the second warship after about 10 minutes of high speed running, zig-zagging, and making a series of sharp turns. Kelly set a course for Cebu City.

Bulkeley saw most of the action, including PT-34 attacking Kuma. The squadron commander’s diversionary actions did little to fluster the Japanese. He noticed “the enemy ship was observed to be totally enveloped in a heavy brown yellowish cloud of smoke. Her searchlight beam was growing weaker by the moment,” he wrote. “PT-34 appeared to have hit her.”

Bulkeley wanted to get a closer look at what he was certain was a sinking enemy cruiser. He thought better of it after suddenly spotting another Japanese ship. Thinking the route to Cebu City was blocked by enemy warships, he set a course for the large southern island of Mindanao.

The end of the battle allowed Robert Kelly to assess the condition of his boat. He directed two sailors to take the wounded Reynolds below deck to the forward compartment “and find out how badly he’s hurt.” They administered first aid in an attempt to slow the bleeding and gave the gunner a smoke.

The boat escaped any serious damage from large caliber shell hits but was riddled with many small bullet holes. Her main mast was shot away, putting the radio out of action. “Our victory emblem had been shot down,” Richardson lamented after finding the boat’s souvenir mounted Japanese bayonet was gone.

The sudden spotting of a Japanese destroyer abruptly ended the short lull in action. “Only by swerving to the left was a collision avoided and we passed down their starboard side close aboard without their firing a shot,” Kelly wrote of the encounter. “They immediately turned and commenced pursuit, illuminating us with their searchlight and taking us under fire with their main battery.”

The chase was over by about 1:30 a.m. when PT-34 pulled five or six miles away from the enemy warship due to her faster speed. The sailors continued to see enemy searchlights far to the south for another half hour. “After the danger was past, all hands were secured from general quarters and the regular watch was set,” Richardson recalled. Glancing off into the distance he saw “the moon came up in full splendor over the hills of Bohol, lighting the whole coast with a lunar brilliance rivaling the sun.” Many of the crewmen, with the exception of the injured Reynolds, later gathered near the conn to talk about the battle.

As PT-34 made for Cebu City the calendar passed to April 9 with her sailors believing they had sunk a Japanese cruiser. However, postwar records revealed no enemy ships were sunk during the battle. The Kuma reported one torpedo hit far forward. The weapon failed to explode and broke in half.

Robert Kelly’s boat never made it to Cebu City. The men were operating in narrow waters leading to the harbor with no detailed charts of the area—challenging conditions for even the most experienced sailors. “Although it was a bright moonlight night, navigation was still difficult,” Richardson recalled. There were various shoals, mountains in the background, and few recognizable points to aid in navigation.

PT-34 was inching forward at idling speed with skipper Kelly at the wheel. Something seemed amiss to Richardson. “There was a gentle grating and we were aground,” he wrote. Crewmen shined a flashlight over the side. They could see about 20 feet of depth in the water—plenty of room for a PT boat. However, pinnacles of sharp coral were spiraling upward to within five feet of the surface like a petrified forest. She was hung up on the coral short of the harbor during the early morning darkness.

Kelly decided to send Richardson ashore in a small row boat to find an army doctor to help his wounded man and to see about locating a tugboat to help free the PT. “As I was getting dressed, the punt was lowered into the water,” Richardson recalled. “I strapped my service .45 automatic pistol to my waist and put on my cap (which was never worn underway because of the wind) and boarded the punt.” Two sailors rowed the boat nearly 200 yards to the shore. “After stumbling in the rough sand filled with crab holes, I arrived at a fisherman’s hut and yelled,” Richardson continued. He was soon on his way to a train station a mile away.

The sailors aboard PT-34 shed clothing and went over the side to help free the boat. They eventually dislodged her after a concerted effort. By then it was about 4:30 a.m., and daylight was fast approaching.

Robert Kelly was faced with a critical decision on how to proceed when morning light revealed a thick blanket of low fog. The boat captain decided to wait until about 7:30 a.m. after some of the fog burned off before entering the channel. “Under ordinary conditions it would have been considered suicidal to have been operating in this area after daylight,” Kelly wrote about the threat from Japanese planes. “However, the army authorities had assured us of air cover and given us the assigned radio frequencies of the planes. These planes were scheduled to arrive that morning from Australia to form an escort for coastal steamers due to leave Cebu the next day carrying food for Corregidor.” With his radio knocked out during the battle Kelly had no way to confirm the arrangements.

Unaware of the events aboard the boat, Iliff Richardson made it to a small village about nine miles south of Cebu City. He phoned the local army headquarters. “I requested the officer on duty to send a tug to Minglanilia and to have an ambulance at Pier I in Cebu at 5 a.m. to pick up a wounded man; also to have everything ready [to] place four more torpedoes aboard the 34 and the same for the 41,” he wrote. “This last statement made the officer at the other end of the line curious so I told him we had had an engagement with the Japanese cruiser.”

Richardson returned to the beach to find no sign of his boat and quickly deduced she had freed herself. He frantically canceled the request for the tugboat and waited for his PT to arrive. The clearing of the morning fog allowed him to see some type of action taking place in the distance involving planes and a small boat. Richardson suddenly realized it was PT-34 under attack!

The air attack started with a bomb exploding off PT-34’s port bow just after 8 a.m. The explosion blasted a hole in the crew’s washroom, disabled one of the machine gun mounts, and damaged the windshield in the conn. “We had not heard any planes due to the noise of our engines,” Kelly recalled. “Four Japanese float planes were seen to be diving on us out of the sun, the first already having dropped its bomb.” The PT sailors were taken by complete surprise.

The attackers were most likely Mitsubishi F1M “Pete” floatplanes from the seaplane tender Sanuki Maru. The machine guns aboard the PT quickly opened fire as crewmen rushed to break out extra ammunition. Skipper Kelly had limited options to maneuver due to the confined waters of the channel.

Gunners were able to extract a small amount of revenge when a stream of bullets hit one of the attackers. The plane began to trail smoke but was not seen to crash. All of the guns eventually fell silent with some of the gunners dead or grievously wounded.

The attack lasted for about 15 minutes with eight bombs exploding in the water and near misses causing additional damage to the boat. The PT was riddled with bullet holes. “When I received word that the engine room was flooded with about three feet of water and the engines could not last much longer, it was decided to beach the boat since we could no longer fight,” Kelly reported. The boat went aground near Kawit Island just south of Cebu City. It was 8:20 a.m. All the sailors could do was pull the wounded men off the boat to a safer place ashore as the enemy planes made additional strafing runs.

Two sailors from PT-34 were killed and several more wounded. The surviving crewmen returned to the damaged boat later in the day to salvage any equipment still usable. The Japanese planes returned to make additional attacks with bombs and machine guns. “The bombs missed but the boat was set afire and exploded, the gas tanks apparently having been hit,” Kelly explained.

The end of the defense of the Philippines was soon at hand. The beleaguered defenders on Bataan surrendered on the same day PT-34 was destroyed. The island of Corregidor—and the remainder of the Philippines—capitulated about a month later.

Robert Kelly was among the servicemen escaping to Australia via air evacuation. He later commanded a squadron of PT-boats in the South Pacific. Iliff Richardson was not as lucky. He was unable to escape after the surrender and decided to join the Philippine guerrilla movement. He remained in the Philippines until his rescue in late 1944.

Awesome article keep the good job

As I recall, there was also a version with 18 inch torpedo tubes. Don’t have much info about them but seem to remember they also mounted 20mm guns.