By Alex Zakrzewski

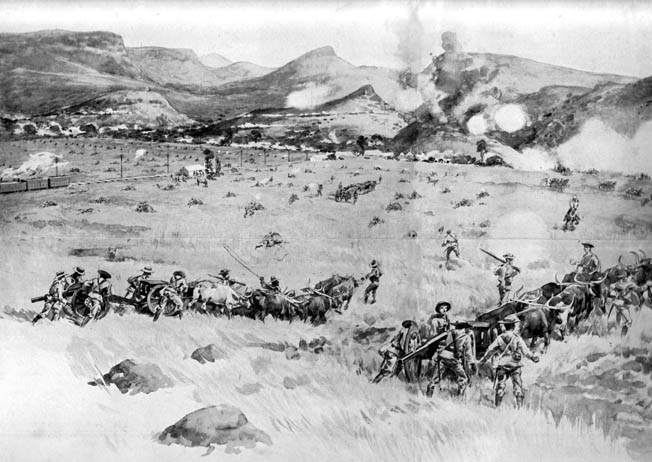

On the morning of December 15, 1899, the serene, windswept wilderness of northern Natal was punctuated by the sound of 18,000 British soldiers trudging north to relieve the besieged town of Ladysmith. Despite the heat, flies, and swirling clouds of red dust–, the men were in good spirits as they approached the Tugela River, once the southern frontier of the mighty Zulu Kingdom.

Their high morale was in large part inspired by the reputation of their vaunted commander, General Sir Redvers Buller, a decorated hero of the British Empire. Buller had decided to make his crossing at Colenso, a tiny village on the southern bank of the Tugela, less than 24 kilometers south of Ladysmith. Looking down on Colenso from the northern bank was a series of koppies. These dome-shaped hills rise out of the South African plain like giant mushroom clumps. Buller knew that somewhere in the hills there waited a Boer force that was determined to keep him from crossing. But while he expected a stiff fight, he did not foresee the bloody disaster that was about to unfold.

Buller had arrived in South Africa on October 31, 1899, to a rapturous welcome from the Cape Colony’s British inhabitants. A large, barrel-chested man with a stern, bewhiskered face and narrow, humorless eyes, he looked to be the very epitome of the Victorian officer and gentleman. Over the course of his 40-year career he had seen extensive service throughout the empire and was no stranger to Africa. But beneath his stolid façade and illustrious reputation, Buller was a man suffering from anxiety and self-doubt. He was a competent and brave officer, but he lacked the skill and ingenuity required to carry out large, complex operations on a modern battlefield. Specifically, he clung to outdated tactics, doctrines, and traditions. If he had one saving grace it was that unlike his colleagues, he was clever enough to realize his own shortcomings and initially turned down the commander-in-chief role. It was only after a buoying conversation with friend and mentor Sir Garnet Wolseley that he agreed with deep misgivings to command the campaign that would ruin his career and reputation.

The Second Boer War had its roots in the growing tension in the second half of the 19th century between Great Britain and the Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State. Following its acquisition of the Cape of Good Hope via the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, the British had steadily expanded their presence in the region. The discovery of gold in the Transvaal in 1886 sparked a flood of immigration into the republic. The British-owned mines stripped resources from the Transvaal to sustain the vast British Empire, and the Boers resented that fact.

In response to Boer hostility, the British expanded their military presence in Cape Colony and Natal. In 1896, Transvaal President Paul Kruger gave the British an ultimatum to stop building up their forces or face war. On October 12, 1899, the Boer republics declared war.

The agrarian, underdeveloped Boer republics had a scattered white population of barely 250,000. Against them stood the limitless resources of an empire that encompassed a quarter of the world’s land area and a fifth of its people. The British public had welcomed the outbreak of hostilities with a wave of unrestrained patriotic fervor, and everyone expected a quick and resounding British victory. The London newspapers even went so far as to dub the conflict a “tea-time war” and boldly predicted that it would all be over by Christmas.

Buller’s plan for the campaign was a straightforward march across the Boer republics from Bloemfontein to Pretoria using the main railway as a supply line. With their capitals captured, he reasoned that the Boers would quickly lose heart and sue for peace. It was a blunt and unimaginative strategy, but one that had worked well for the British Army in recent colonial campaigns. While en route from Europe Buller was encouraged by the news that the Boers had been defeated in three of the war’s opening engagements and had every reason to expect the war to be over in a matter of months. But within hours of arriving in Cape Town, he learned that the military and political situation was considerably more complicated than he envisioned. His plans would have to be hastily scrapped and a whole new strategy conceived.

In northern Natal, Lt. Gen. George White had ignored orders to redeploy on a much more tenable line south of the Tugela. As a result, on October 30, 1899, a date remembered in the British Army annals as “Mournful Monday,” he suffered a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Nicholson’s Nek and was forced to retreat to Ladysmith where his large force of 13,000 men was besieged. In the eastern and northern capes, British garrisons had similarly been surrounded at the mining towns of Kimberley and Mafeking. Much to everyone’s surprise, the highly mobile commandos had seized the initiative and succeeded in trapping half the British troops in South Africa in a series of remote outposts at distant ends of the country. They appeared poised to strike into the very heart of the Cape Colony and Natal.

When news broke of the Boer successes, the British public was shocked and called for an immediate relief of the beleaguered garrisons. Complicating the situation was the presence in Kimberley of internationally renowned mining tycoon Cecil Rhodes, one of the great champions of colonial expansion in southern Africa and arguably the British figure most hated by the Boers. The commandos had barely completed their encirclement of the town before Rhodes began haranguing Buller, his political friends and the press with frantic calls for relief, further inflaming public opinion in the process. Equally panicked by the disastrous turn of events was Sir Alfred Milner, the Cape Colony’s scheming governor and one of the main instigators of the conflict. Milner did not trust the Dutch-speaking inhabitants of British South Africa any more than he did their cousins in the republics. With the Boer commandos seemingly at the gates, he began to see signs of rebellion everywhere and urged Buller to pacify Cape Colony before doing anything else.

Buller was quite right to complain that his task had suddenly changed from an invasion of the Boer republics to a conquest of the whole of South Africa, a job for which his army corps of 47,000 was both inadequate and unprepared. Nearly half of his total strength was composed of raw reservists with no combat experience and unready for the harsh conditions of the veldt. He was also desperately in need of trained staff officers and an effective intelligence apparatus through which reliable information on the strength and composition of the Boer forces could be ascertained. Even basic maps of the region were in short supply and those that were available would prove cripplingly inaccurate. Though no one knew it at the time, the British Army had fallen embarrassingly behind in the all-important field of intelligence gathering. It was a fatal flaw that the British Army would pay for in blood in the months to come.

To fulfill all the objectives he was under tremendous pressure to achieve, Buller decided to divide his corps into three unequal columns and give each a different assignment. He would lead the largest north through Natal to relieve White and free the sizable force trapped at Ladysmith. At the same time, Lt. Gen. Lord Methuen was to advance north along the Western Railway with his division of about 12,000 men and free Kimberly. In addition, Lieutenant William Gatacre in Cape Coloney was given a brigade with which to seize the railway junction of Stormberg, a move that was hoped would both pacify the region and preclude the commandos from striking farther south. In hindsight, it seems absurd for Buller to have divided his untested corps and sent it piecemeal in opposite directions across a hostile wilderness to confront an enemy about which little was known. At the time, though, the British generals’ estimation of the Boers’ fighting qualities was so brazenly low that even Buller expected a walk-over. All three generals would soon get more fighting than they bargained for.

On November 22, Buller left the Cape for northern Natal to join the troops being assembled at Frere, a sleepy railway stop roughly 20 kilometers south of Colenso. Most of his corps was still en route from Europe and had to be hastily diverted from Cape Town to Durban, where the seasick soldiers were immediately packed in open carriage trains and sent north. By the time the men arrived at their destination, they were half starved, rain soaked, and covered in soot from the train chimneys, but in surprisingly good spirits. Day and night the troop trains poured into Frere, transforming the hamlet into a sprawling city of white tents that was soon home to the largest British field force since the Crimean War. Within just a few weeks, Buller had at his disposal four infantry brigades, a cavalry brigade, and 44 pieces of artillery, including 12 12-pounder naval guns.

Buller arrived in Frere on December 6 and immediately began wrestling with the all-important question of where to cross the Tugela. The river, which was 91 meters wide with steep banks and fast-flowing water, was an intimidating obstacle in even the most peaceful of conditions. What is more, the river could only be forded at certain points. The most obvious place to cross was at Colenso, which lay less than 20 kilometers north of Frere along a main road through open country. It also offered two bridges across the river, one of which the Boers had blown. But while the south side of the river was an undulating plain with few natural obstructions, the koppies on the northern bank were a natural fortress that would certainly be heavily defended by the Boers. Initially, Buller recognized the perils of crossing at Colenso, and on December 8 he announced that he instead planned to cross 24 kilometers upstream at a place called Potgeiter’s Drift. The latter route, while longer, also offered a road that led straight to Ladysmith, and Buller hoped that a crossing there might further flank any Boers entrenching themselves at Colenso. He even ordered one of his infantry brigades to begin marching on Colenso in order to keep any Boers there in place. Just as he was setting out on his flanking march, events beyond his control once again forced him to scrap his plans.

On December 10, 1899, Gatacre stumbled into a Boer ambush during an ill-planned night attack on the commando at Stormberg and lost 600 men in the process. The following day, Methuen was badly mauled during a predawn attack on the Magersfontein heights, during which the vaunted Highland Brigade in particular suffered terrible casualties in the face of concerted and concealed Boer rifle fire. To make matters worse, while the pride of Scotland was being decimated in front of the Boer trenches, those British troops that actually managed to scale the heights were inadvertently pelted with shrapnel fire from their own guns. By day’s end, almost 1,000 men had been lost, and the advance to relieve Kimberley had been humiliatingly stopped in its tracks.

These defeats exponentially increased the pressure on Buller to relieve Ladysmith as soon as possible. The empire’s honor was more at stake than ever as all eyes were firmly fixed on events in Natal. Whereas a stronger, more decisive commander would have stuck to his original plan, Buller characteristically bowed to the popular pressure, and on December 12 he gave orders to abandon the flanking maneuver and cross the Tugela at Colenso. He even sent a signal to White indicating that he planned to attack on December 17 and ordered him to mount a simultaneous attack to the south. Then, without bothering to notify White, on December 14 he inexplicably changed his mind again and issued orders for a predawn attack the following day. These were the actions of a commander utterly out of his element, and the fact that none of his staff raised any concerns over this series of contradictory orders indicates that most of his officers were as well. Unfortunately for them, and particularly so for the rank and file, they were about to face a brilliant opponent whose troops could not have been more in their element.

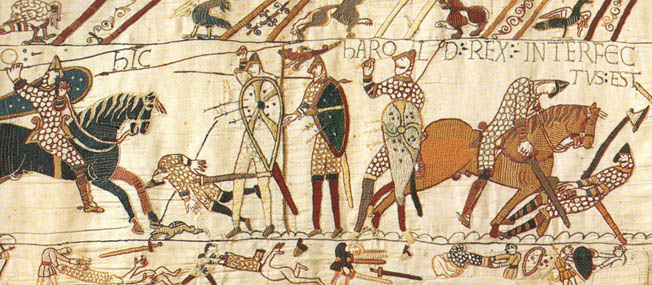

The armies of the Transvaal and Orange Free State were composed almost exclusively of citizens’ militias that at the outbreak of hostilities combined to number around 47,000 men. In times of war, every able-bodied male between the ages of 16 and 60 was required to report to his local commando, bringing with him only a sturdy horse and enough rations to see him through the next few days. Because no uniforms were issued, the men fought in their civilian clothes with some even sporting their Sunday’s finest, including top hats and tails. All officers including the commandant were elected and all major decisions were made during war councils in which all of the men voted on the next course of action.

The democratic nature of the commando system lent itself to indiscipline, and it was not unusual for men to simply pack up and leave for home when they disagreed with their officers. But when properly motivated, a Boer in the field was an extremely dangerous adversary. Most Boers were frontier farmers, raised in the harsh conditions of the veldt and taught from an early age how to ride and shoot. Through centuries of warfare with much larger native tribes, they had also learned the importance of mobility and concealment, two skills made all the more deadly by the introduction of smokeless powder ammunition.

Before the war, the Boer republics had purchased large quantities of German-made Mauser rifles, which took a five-round magazine that allowed for a greater rate of fire than the Lee-Enfields and Lee-Metfords carried by the British troops. The Mauser also boasted a higher velocity and better accuracy. Stormberg and Magersfontein showed how a determined, well-concealed group of Boers, armed only with Mausers, could stave off a much larger attacking force. It was a lesson the British would be taught many more times by war’s end.

The Boers at Colenso numbered 4,500 men, but were extremely fortunate to have a tactical genius as their commander. General Louis Botha was a successful farmer and a well-respected member of the Transvaal parliament. He had curiously abstained from voting on the question of war with Great Britain but dutifully joined his commando when hostilities arose. Despite his reservations, he quickly distinguished himself as a natural soldier and a brilliant tactician with a remarkable ability to inspire the men he led. When elderly Commandant-General Piet Joubert fell from his horse, the 37-year-old Botha was handpicked to become the youngest commandant in the Boer army.

Botha took one look at the field around Colenso and immediately recognized that it was ideal ground for defense. The northern bank of the Tugela is dominated by a chain of high koppies, and the river itself follows a meandering, serpentine course that creates a series of great loops. The actual village of Colenso lay in the middle of one of these loops, which meant that a force moving through the village would be subject to fire from three sides. Northeast of the village there was also a fortified hill called Fort Wylie that completely commanded the ground below. There was another crossing point farther west, but its location was the subject of much confusion among the British, partly because of the lack of adequate maps and partly because of the river’s erratic route. Four kilometers west of Colenso, the river suddenly reverses course before once again assuming its original path. The result is a large, narrow, westward-facing salient that resembles a thumb or horse’s nose, at the apex of which there was an old ferry crossing that was no longer in service but could still be reached by a worn path. Farther west of the loop there was a fordable point called the Bridle Drift. In the days to come, this confusion over just where the westerly drift lay would have disastrous consequences.

Botha’s plan was to funnel the attackers toward the crossings then trap them between the river and his own positions. He placed the bulk of his men below the Colenso koppies that overlooked the village and in well-camouflaged trenches along the northern bank of the Tugela all the way to the Bridle Drift. It was also in the Colenso koppies and in the Tugela Heights north of the salient that he positioned his 12 artillery pieces, which included 10 Creusot and 75mm antipersonnel guns, one 5-inch Krupp Howitzer, and a 1-pound quick-firing Maxim-Nordenfeldt “pom-pom” auto cannon. The crews of these gun were excellently trained and among the only military units in both republics to receive uniforms. Also dispersed throughout the Boer lines was a battalion of Irish and Irish-American volunteers called the Transvaal Irish Brigade.

Botha’s plan presupposed in many respects the killing fields of the western front 15 years later during World War I. Positioning his men below the high ground meant that his Mausers would fire on a flat trajectory, a factor that drastically increased their range and lethality. Occupying the lower ground also had the added benefit of misdirecting the British artillery fire, which would instinctively assume that the Boers would occupy the highest ground available. Perhaps his most innovative and forward-thinking measure, though, was his use of weighted coils of barbed wire that he placed along the river bed just below the water.

The only problem Botha faced was what to do about Hlangwane Hill, a low mountain one kilometer east of Colenso. East of the village the Tugela suddenly turns north and the mountain lies on the river’s eastern bank, which made it an unappealing spot to garrison because its defenders would be pinned up against the river should they have to retreat. But it was also a crucial position because it offered a complete view of Botha’s lines and a perfect spot to enfilade his positions. It was only after much cajoling and a telegram straight from Kruger that Botha was able to convince a few hundred Boers to occupy this vulnerable position. Beyond that, the Boer commandant could do little more than hope and pray that Buller would fail to realize the unique opportunity Hlangwane provided and instead walk straight into the trap being set along the river crossings.

Buller could not have been more obliging. Since December 12, his artillery had been shelling the koppies in anticipation of the coming crossing. But while the British knew that the Boers were waiting for them in Colenso, no one bothered to properly reconnoitre their positions. Had someone done so, they would have learned that the lyddite shells were exploding harmlessly over empty ground. Nor did anyone seem to recognize the importance of Hlangwane, which lay unoccupied by the Boers until the eve of battle on December 14. Had Buller abided by the most basic of all military maxims and taken the high ground, he would have gained the tactical advantage. Botha, in danger of having his left flank rolled up, would most certainly have had to change his strategy if not withdraw altogether. Alas, Buller had none of the skills or insight necessary to make such a sweeping assessment.

On the evening of December 14, Buller’s brigade commanders received their orders for the coming day. His plan called for a three-pronged assault over a wide front of roughly 11 to 12 kilometers. In the center, Maj. Gen. Henry J.T. Hildyard’s 2nd “English” Brigade was tasked with seizing the village of Colenso and its bridges. At the same time upstream, Maj. Gen. Fitzroy Hart and the 5th “Irish” Brigade were to cross at the Bridle Drift and then advance downstream to back up Hildyard. The 2nd and 5th Brigades would be joined by the 4th “Light” Brigade under Maj. Gen. Neville Lyttleton, which was ordered to advance toward the Tugela between the Irish and English Brigades, ready to support either if need be. All the while, on the extreme right, Lord Dundonald was to take his Cavalry Brigade and engage the Boers on Hlangwane, but was not expressly ordered to take the mountain. Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Barton’s 6th “Fusilier” Brigade was kept in reserve behind Dundonald, and all attacks were to be supported by Buller’s considerable artillery complement.

The next morning, December 15, 1899, the attack began at roughly 4:45 am when the British guns resumed their shelling of the Colenso koppies. Buller’s camp lay only six kilometers south of Colenso, and from his command post on the Tugela heights, Botha soon beheld a great khaki mass of soldiers. By the time the signal to advance was given, Hart had already been drilling his Irish regiments for half an hour. Hart was known to his men as “No-Bobs” because of his stalwart refusal to duck when under fire. But what he had in courage he lacked in tactical sophistication, and on this day he inexplicably chose to deploy his men on the open plain in quarter column, a close formation in which the companies of a battalion marched one behind the other as if on parade with only a space of six paces in between. Hart led his densely packed troops from atop his horse, accompanied by his staff and an African guide that was supposed to lead them to the Bridle Drift.

As the Irish Brigade approached the Tugela it began to veer ominously eastward toward the salient rather than the Bridle Drift to the west. The African guide warned Hart that they were heading in the wrong direction, but the general had spotted the worn path leading to the old ferry crossing and was convinced that he was in the right spot. The Irish pressed on further into the salient, much to the amazement of the watching Boer defenders, whose trigger fingers surely itched at the sight. As the brigade marched farther into the trap, a detachment of Royal Dragoons protecting Hart’s left spotted the Boer trenches in the distance and rushed over to inform him. Once again the brigade commander ignored the information and instead chose to continue on across the sundrenched stillness of the open plain toward the apex of the salient. By 6:30 am, 3,200 men were crammed into a space barely 1,000 yards wide, and the defenders could no longer restrain themselves.

From atop the Tugela heights, Botha’s Creusots suddenly came to life and the first shells crashed in between the Dublin Fusiliers and the Connaught Rangers. Hundreds of Mausers fired by Boer soldiers along the river suddenly crackled to life, unleashing a storm of lead into the neat rows of startled soldiers. In the blink of an eye, the tranquil landscape became a killing ground as men everywhere fell dead or wounded while they sought cover behind the few rocks and scrubby plants that dotted the plain. Hart, true to his reputation, refused to duck and instead strode calmly up and down his lines, urging his men forward. They dutifully did as instructed, though all cohesion was quickly lost as units became mixed and officers separated from their men.

The khaki-uniformed British troops lurched on in the face of a withering fire from all directions. Behind them there soon appeared a grim trail of bloody, mangled bodies lying prostrate beneath the intensifying summer sun. A handful managed to find cover in an abandoned kraal and a courageous few even managed to make it to the river where they searched desperately for a point to cross. Some became entangled in the barbed wire coils hidden beneath the water and were either picked off with sickening ease by the defenders or taken prisoner. Among those that made it to the water but no further was a fourteen-year-old Bugler named John Dunn. The boy had ignored his Captain’s orders to stay safely behind the fighting and bravely joined his brothers in the front ranks where he sounded the advance until wounded in the chest and arm, losing his bugle as result. By 7 am the Irish Brigade was trapped.

In the center, events unfolded just as disastrously. To cover Hildyard’s advance, Colonel Charles Long was given two batteries of field pieces and six naval guns. Buller made clear that he was to remain well behind the advancing infantry with Barton’s brigade, using only his long-range naval guns to fulfill orders. Long had other ideas. “The only way to smash those beggars is to rush in at ‘em,” he said, and raced off with his field guns without either informing Barton or waiting for his ox-drawn naval guns to catch up. When he reached a point only 914 meters from the nearest Boer trench and almost a kilometer ahead of Hildyard’s infantry, his superbly trained crews unlimbered their guns and, with parade ground precision, formed a perfect firing line.

From his command post, Botha could hardly believe his eyes. Sitting in the open plain with no cover or infantry support were 12 British field guns seemingly ripe for the picking. His men in the trenches did not need to be told of the incredible opportunity that had presented itself, and they immediately trained their fire on the stranded gunners. To their immense credit, Long’s gun crews acted as if impervious to the hail of Mauser bullets whistling overhead, and they serviced their guns with such patience that Fort Wylie was soon a cloud of red dust churned up by their well-aimed fire. They even counted out the intervals between shots as if they were on maneuvers.

Lumbering along behind the field guns were Long’s six naval guns. As they struggled to keep up with their overzealous commander, they came under fire from the Boer pom-pom, which scared away their African drivers. Luckily, they had advanced far enough to join in on the action and they too were soon pounding the Boer positions. Unfortunately, the infantry support was still far behind and it was not long before the field guns began to run out of ammunition. The ferocious Boer fire also began to take its toll on the gun crews. Long himself was wounded by shrapnel in the arms, liver and kidneys and had to be dragged back to the shelter of a donga (dried-out river bed) about 365 meters behind his batteries. The rest of his men fired off their remaining ammunition then joined their injured commander in the donga to await the infantry. It was only 7 am and they had already fired 930 rounds, yet the Boers remained firmly fixed in their positions. As the gunners peered cautiously over the lip of the donga, they could see their guns standing in perfect line amid a fury of whizzing bullets and bursting shells. When someone wondered aloud whether the guns would have to be abandoned, Long was aghast. “Abandon be damned! We never abandon guns!” he said before drifting off into delirium.

Buller watched the opening stages of the battle from a hill where his own naval guns continued to blaze away. As he sat snacking on some sandwiches, he could see little of what was going on but enough to determine that Hart was in the wrong place. When he learned just how much trouble the Irish were in, he jumped onto his horse and made straight for Lyttleton’s camp with his staff in tow. “Hart has got himself into a devil of a mess,” he told the 4th Brigade’s commander. “Get him out as best you can.” Lyttleton did as instructed and, unlike Hart, prudently extended his men in a loose formation across the mouth of the salient to provide covering fire for the Irish to retreat. Slowly but surely, groups of exhausted, thirsty men began to trickle back out of the jaws of death, many carrying wounded comrades. Among them was the young John Dunn. He would recover from his wounds and return home to receive a hero’s welcome and new bugle personally from Queen Victoria. Regrettably, some forward units did not receive the order to withdraw until much later and remained pinned down for hours in the blistering heat. Much later they would learn that among their tormenters that hellish day were fellow Irishmen.

The sight of Hart’s Brigade returning beaten and bedraggled planted the germ of defeat in Buller’s mind, and his thoughts immediately turned to disengagement. After ordering Lyttleton not to get too committed, he rode out to the center to see for himself the progress being made by Hildyard’s Brigade, only to discover that Long’s guns were out of action and sitting unattended only 914 meters from the Boer positions. At great risk to himself, Buller immediately rode over to the donga where he found Long covered in blood, raving incomprehensibly about his poor gunners. Buller realized that the situation was worse than he feared and all thoughts of doing anything other than rescuing the stranded guns instantly disappeared from his mind.

Had Buller had the emotional and mental fortitude to forget for a moment the plight of Long’s field batteries and examine the bigger picture, he would have seen that the overall situation was not as bad as he feared it to be. In the center, Hildyard’s Brigade made excellent progress and managed to seize Colenso and the crossings with relatively few casualties. Some of his units in the village had even begun returning fire on the Boer trenches and succeeded in forcing some defenders to abandon their positions and seek higher ground. Buller also had eight fresh battalions and a slew of other artillery pieces at his disposal.

Moreover, east of Colenso, Dundonald had launched a very effective attack on Hlangwane and, supported by the 7th Field Battery, succeeded in making some progress up the rocky slope. The outnumbered Boers fought back stubbornly, and Dundonald was forced to ask Barton for reinforcements. He was confident that with an extra battalion he could storm the mountain and begin enfilading the Colenso koppies. However, despite repeated pleas, Barton refused to act without a direct order from Buller, which he made no effort to receive. As a result, Dundonald’s attack and Buller’s best chance to potentially dislodge the defenders around Colenso bogged down and petered out.

There is a good chance that had Barton asked Buller for permission to engage, he would have been denied anyway. The commander-in-chief had already made up his mind that the day was lost and his one objective before withdrawing was to retrieve Long’s guns. As if to deliberately make the task more difficult, Buller inexplicably ordered the naval guns to the rear of his field batteries to stop firing and prepare to withdraw. Perhaps he feared that they too were in danger of being overrun or destroyed, even though they were just beginning to succeed, along with Hildyard’s Brigade, in quieting some of the Boer trenches. Whatever the reason, the exhausted sailors, their oxen killed and African drivers scattered, were forced to laboriously turn their guns and pull them back to camp.

With no artillery to worry about, the Boer trenches once again sprayed the ground around the guns and donga with a devastating fire. Seeing no other recourse, Captain Harry Norton Schofield, Buller’s aide-de-camp, bravely stepped forward and offered to launch a rescue operation. He was joined by Corporal George Nurse and seven other gunners from Long’s batteries. Buller ordered his staff to assist. Captain Walter Congreve of the Rifle Brigade and Lieutenant Freddie Roberts, son of Lord Frederick Roberts, England’s most famous living soldier, stepped forward to answer the call. Nurse later recalled the “perfect storm of shot and shell” the rescue team faced. Even before they mounted, a shell burst overhead and blew the eye out of one of their horses.

Regardless, the rescue team galloped courageously, with Roberts reportedly laughing and waving his riding crop as if on a fox hunt. When they were within 90 meters of the guns, Congreve was wounded in the leg, toe, elbow, and shoulder and thrown to the ground when his horse was shot out from under him. A little farther on, Roberts’ mount also suddenly reeled and he too fell to the ground, mortally wounded in three places. Schofield, Nurse, and the rest of his team made it to the guns, and with bullets “pattering around us like hail,” they somehow managed to limber three before beating a hasty retreat back to the donga. As they were returning, a lucky Boer shell struck one of the three guns, turning it on its back and rendering it unsalvageable. The other two were safely returned to the donga where a lucky Schofield counted six bullet holes in his uniform. Nurse had his finger shattered in two places but was otherwise unharmed. Congreve was able to limp back to the donga where he was treated by a member of the medical team. When the two noticed that the Boers’ were concentrating their fire on Schofield, Nurse, and the rescue team, they gallantly rushed out onto the plain to pull the dying Roberts to the safety of the donga. Two more attempts were made by other gun crews, but they were cut to pieces with heavy loss of life before even coming close to the guns.

Buller calmly watched these events take place without any change of expression. However, his austere appearance belied the fact that he was on the verge of a breakdown. He had also suffered a badly bruised rib from a spent piece of shrapnel and his personal surgeon had been killed beside him. After the battle he would complain that he had been “sold by a damned gunner.” In reality, while Long had certainly put him in a terrible spot, Buller could have waited until nightfall and then under the cover of darkness withdrawn the guns with relative ease. But at that moment in the donga, as he gazed at the chaos swirling around him, the dead and wounded men lying at his feet, none of this crossed his mind. At around 11 am, he made the decision to leave the guns and call off the action. Some of Hildyard’s men in Colenso pleaded to be allowed to hold their position and cover the abandoned guns, but Buller would hear none of it. Up and down the front the order to withdraw was given, and his disconsolate men had no choice but to begin the long march back to Frere.

Not everyone received the order. Out on the plain south of Colenso to the west of the guns, Lt. Col. George Bullock retained his position in another small donga. At around 4:30 pm, the Boers slowly crept across the river to carry away their prize, only to be fired upon by Bullock’s men. The Boers offered to parlay, and while negotiating took the opportunity to surround the donga. When he realized what was happening, Bullock reached for his revolver but was promptly bashed in the face by the butt of a Boer rifle. He and 125 men were taken prisoner and the 10 remaining guns were carted away and shipped to Pretoria where they were put on display as war trophies.

Buller had suffered 1,127 casualties, including 143 killed and 240 missing, presumed captured. He had also lost 10 of his 44 guns. Botha reported only 40 casualties, including just eight men killed. It was a humiliating and lopsided defeat that was further exacerbated by the grueling march back to Frere.

When news reached home of the defeat, the British public was aghast. It was the third and worst defeat in what the press quickly dubbed “Black Week.” Buller, his nerves shattered, permanently tainted his own reputation by signaling White in Ladysmith and advising him to fire off his remaining ammunition and surrender. White ignored him, but word quickly spread of Buller’s shameful defeatism. Three days after the Battle of Colenso, Buller was replaced in South Africa by Lord Roberts.

The captions to the portraits of Botha and Buller are swapped.

Thanks for the correction.

You are welcome!