By Cleve C. Barkley

The darkness held a terror of its own—any false movement or unwarranted sound could easily betray the presence of the 16-man patrol that crept ever closer to the enemy lines. It was barely past 11 pm, and so far the patrol had slipped up to the German strongpoint undetected and now deployed along the base of one of a series of troublesome hedgerows that had been dubbed “Kraut Corner.” The corner—a position that bristled with German machine guns and mortars—had been ferociously defended during two previous attempts to take it the preceding month and had been the source of grievous casualties. Now, in the late hours of July 6, 1944, the patrol, led by 1st Lt. Ralph Winstead of Company E, 38th Infantry, had the mission of not only harassing and disrupting the enemy but also garnering information regarding the mini-fortress’s weapons disposition.

Just minutes earlier the patrol had bellied over its own hedgerow under cover of a heavy artillery and mortar concentration to mask its approach. The enemy lines were in such close proximity that they reached their destination within five minutes. From behind the shaggy barrier was heard the occasional flash and thump as enemy mortars fired. Elsewhere, bright tracers stitched the darkness as a machine gun released chilling, sporadic bursts.

On command, the patrol’s demolitions men pitched their explosives over the hedgerow wall in an effort to stun the defenders. Just as one of the demolition men, Pfc. Louie, rose to drop his satchel charge, a German machine gunner opened up from a firing slit directly below him. Bullets flashed between Louie’s straddled legs at 1,200 rounds per minute. He later admitted that his heart was lodged squarely in his throat as he released his charge. As one, the satchel charge and a Bangalore torpedo lit up the night, followed a moment later by a second satchel charge. Then the assault team sprang into action.

In a flash they were among the enemy, firing rapidly and creating havoc. The shocked Germans responded with unbridled fury. A pointblank firefight erupted as gunshots and explosions rent the night. Within a half hour, the patrol scrambled back to the American lines, assisting three wounded comrades in the process. Upon his return, Lieutenant Winstead reported excellent results: an estimated 11 enemy soldiers had been killed or wounded; two mortar emplacements had been identified as well as the locations of several machine-gun positions—information coveted by intelligence officers as plans were made for an upcoming all-out assault. The objective of the attack would be Hill 192, the commanding height that guarded the city of St. Lo, the prize of the campaign.

Celebrated as the Winstead Raid, the foray of July 6 was but one of many attempts to inflict damage on or gain knowledge of the German defenses on the dominant height. Because of an ever vigilant enemy, Winstead’s patrol was the only one that achieved any semblance of success. All previous incursions had been terminated by a deluge of machine-gun and mortar fire. To the GIs of the 2nd Infantry Division entrenched in its shadow, Hill 192 seemed impregnable.

Hill 192: The Fortified Key to St. Lo

“Take St. Lo,” General Patton had boasted, “and we will be in Paris within two weeks.” It was early July 1944, and the Allies were in a virtual stalemate with hundreds of thousands of soldiers boxed in along their narrow Normandy beachhead. The grand push inland following the June 6 D-Day assault had quickly petered out and had lapsed into a grueling war of attrition among the dreaded hedgerows. Fought to a standstill, the First U.S. Army dug in, stymied by the Norman terrain.

St. Lo, lodged on an elbow of the Vire River, was a prime objective for First Army. Its military significance lay in the fact that St. Lo was a hub for a radiating network of highways and railroads leading to all parts of Normandy and the interior of France. The Germans could easily counter Allied threats in any sector, shifting their forces by means of these connecting roads. Conversely, by taking St. Lo the Americans would not only split and disrupt the German Seventh Army, but also gain control of the road net that was vital to the planned breakout and drive into the heartland of France.

Before the city could be taken it was necessary for the Americans to capture the commanding heights that surrounded it, and the prevailing height was Hill 192, located a few miles to the east. From its peak the Germans held the perfect surveillance post and had even built an observation tower from which they could not only monitor Allied movements in the immediate vicinity, but as far back as the English Channel. As a consequence, the Americans could not move without drawing fire. It was essential that Hill 192 be taken.

As an obstacle, Hill 192 was not very daunting, rising rather gradually to its flattish summit perhaps 55 yards or so above the surrounding countryside. The problem lay in the fact that like all of Normandy it was covered by the ubiquitous hedgerows. These solid earthen dikes ranged anywhere from four to nine feet in height and several feet thick, each completely covered by shaggy vegetation with trees sprouting from their crests, obstructing view into the next field. Each tiny Norman field was enclosed by these ancient walls and became a veritable fortress for the defending Germans. Although every field was not occupied, the defenses were mutually supporting and deployed in depth.

General Joseph Lawton Collins, a veteran of the Pacific Theater, remarked that the irregular patchwork terrain was as bad as anything he had seen on Guadalcanal. American tanks could not penetrate the thick walls; therefore, they could not accompany infantry attacks. As a result, the infantry was compelled to go over the top, just as their fathers had done from the trenches of World War I, in near suicidal frontal attacks.

Elite Fallshirmjägers vs the ‘Indianhead’ 2nd Infantry

The forces that held the hill were elements of Maj. Gen. Richard Schimpf’s 3rd Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Division, one of Germany’s best. Trained for the assault and honed to the point of fanaticism, the paratroopers were well equipped and armed with mortars and automatic weapons. While roughly equal to the Americans in manpower at the company level, the parachutists boasted 20 machine guns and 43 submachine guns per company, while a U.S. rifle company was equipped with only two light machine guns and nine Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR). Furthermore, the Germans had preregistered virtually every yard of the forward slope for expert mortar and artillery concentrations. The GIs at the front swore that a German mortar team could easily drop a shell in one’s back pocket. It is clearly evident how a German company could be stretched over a wide front but still maintain a cohesive defense against a numerically superior foe.

Entrenched at the northern foot of the hill were men of Maj. Gen. Walter M. Robertson’s 2nd Infantry Division. The men who wore the Indianhead shoulder patch had been embroiled in the tough hedgerow fighting since landing on Omaha Beach on D-Day+1. They held no illusion about gaining the hill easily. In two previous attempts in June the division had sustained 1,253 casualties in three days. The battle would definitely be rough.

The staff at division headquarters produced an intricate plan of attack. In preparation, each assault squad trained with a Sherman tank from Lt. Col. Robert Skaggs’s 741st Tank Battalion and a team of four engineers. The engineers would remove satchel charges from a special rack welded to the tank’s rear deck and blow a gap in the impeding hedgerow large enough for a tank to pass through. Upon entering the field the tank would become the base of fire, employing its 75mm gun to blast suspicious corners of the next hedgerow while its machine guns sprayed the far embankment. Then a pair of scouts would dash forward under covering fire from the tank with their squad mates following soon after. Once the squad secured the hedgerow they would signal the tank forward and the entire procedure would be repeated, field after field, until the hill was taken. To facilitate infantry-armor communication an EE-8 field phone was attached to the rear of each tank, thus solving a problem encountered earlier in the campaign. In addition, each assault company would have the added support of a pair of tank dozers fitted with massive earth-moving blades.

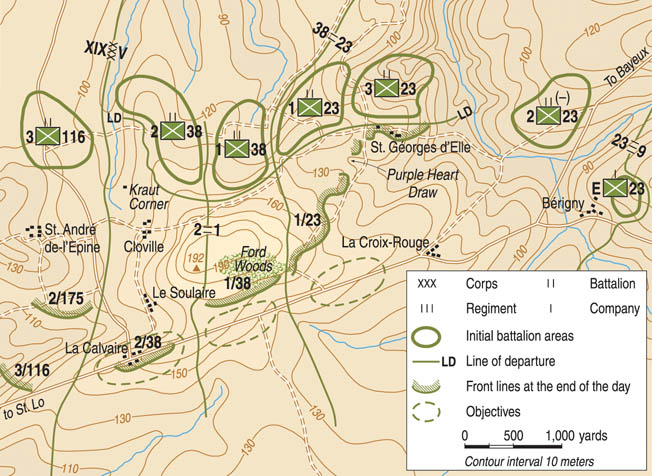

Objectives Around Hill 192

The jump-off time was set at 6 am on July 11, 1944, with the final objective set at the St. Lo-Berigny Highway beyond the reverse slope, some 1,500 yards away. To soften the enemy, eight battalions of artillery were to pound the hill for 20 minutes prior to the attack, then advance their fire by predetermined increments upon request of the infantry platoon leaders. Air strikes were also planned for nearly 200 Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers. Three battalions, the 1st and 2nd of the 38th Infantry and the 1st of the 23rd Infantry, were to make the main assault supported by demonstrations from the balance of the 2nd Infantry Division deployed to their left.

Of tactical significance were three villages and two draws. On the right flank sat Cloville, about 500 yards beyond the line of departure with the tiny hamlet of Le Soulaire perhaps another 500 yards farther and on the reverse slope. Leading up to Cloville was a draw that angled from the right and was guarded by the brutish strongpoint known as Kraut Corner. After horrendous casualties in earlier assaults it was dubbed Dead Man’s Gulch. All of these were in the zone of the 2nd Battalion, 38th Infantry.

On the far left flank and actually straddling the front line was St. Georges d’Elle, a town that had changed hands on numerous occasions, but for now was mostly within the American lines except for a few houses on its southern fringe and farther up the hill. Of additional concern was a deep draw that intersected the route of the 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry near St. Georges d’Elle.

There were also two forests, each suspected of hiding enemy forces. The larger, designated Ford Woods, was diamond shaped and roughly 900 yards wide by 500 yards deep; it spilled over the southeastern slope from a point east of the peak. With the exception of the far eastern corner, the bulk of this forest lay in the zone of the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry. The other, which lay in the path of the 2nd Battalion, 38th Infantry, was much smaller and situated near the peak, just west of Ford. It was called Dodge Woods.

Supporting the Attack on the Hill

The morning of July 11, 1944, was cool and misty. The assault troops had been pulled back several hundred yards at 4 am as a safety precaution against any short rounds of the planned barrage. At precisely 5:40 am, a deep-throated rumbling came from the rear as eight battalions of artillery hurled the first massive salvo upon the hill. Many more followed.

Since the extreme right flank of the 38th Infantry was echeloned farther back because of the contours of the hill, it was decided that 1st Lt. Robert Larson’s Company E of Lt. Col. Jack Norris’s 2nd Battalion would make the first move. Larson launched his attack at H-hour, 6 am, while Captain Vincent Wallace’s Company F would wait until H+20. The 20-minute delay would allow time for the left flank of Company E to come abreast of the right flank of Company F, thereby permitting the battalion to advance up the hill on a unified front. Company G would follow as reserve since it was well under strength due to a severe mauling during a June 16 attempt on the hill.

The first disappointment came when the planned airstrikes were called off due to overcast skies. The next occurred within minutes of H-hour when Company E was greeted by the abrupt stuttering of automatic weapons even before they reached the line of departure. Unknown to them, a number of Germans had noticed the early morning withdrawal and had sneaked forward to occupy the abandoned American positions. As a result, not only did they escape the preliminary barrage but forced Company E to fight its way to its jump-off point. Fortunately, the infiltrating paratroopers were few and quickly routed and the attack resumed.

Grenades Over the Hedgerows

Initially, Company E managed to gain two or three hedgerows with relative ease by employing the new tank-infantry-engineer tactics. But then things worsened. As one, numerous machine guns cut loose all across the front, driving men to ground. Then the dreaded mortars began to fall with uncanny accuracy. Company E had run headlong into Kraut Corner, the formidable fortress that anchored the enemy’s western defenses.

Mortar shells continued to crash with measured cadence, flinging shrapnel in every direction while individuals stumbled forward in the face of galling fire, only to drop again as bullets ripped the ranks. Immediately, Winstead’s 2nd Platoon became pinned down. The 1st Platoon on the left, commanded by 2nd Lt. Charles Curley, faced the same devastating fire, but Curley took the initiative and led his men forward through heavy mortar fire.

One squad reached the enemy hedgerow only to be bombarded by a shower of concussion grenades. Enraged, Staff Sergeant Melvin Kuhlow scrambled to the hedge top and commenced firing rapidly at the defenders below only to fall back dead, riddled by enemy bullets. Desperate GIs flung their own grenades over the earthen dike only to have them come sailing back before they exploded. Noting this, Technical Sergeant Edward Perry of the light machine gun section held his grenades for an interminable three seconds before tossing them, but even that had negligible effect. The accompanying tanks added their heavy firepower to each squad’s effort but with little result. The 3rd Platoon, originally in reserve, was quickly committed on the right but was also pinned and the attack ground to a halt. Company E was being shot to pieces a mere 300 yards from the line of departure.

Recognizing the problem, a sergeant from the 741st Tank Battalion suggested that Lieutenant Curley bring up one of the supporting tank dozers to knock down the hedgerow before them. In short order Sergeant John Brewer’s tank dozer rumbled to the front. After receiving instruction from Curley, Brewer revved his engine and crashed effortlessly through the hedge wall, then pivoted left with his blade lowered to rout the defenders. Terrified, a number of enemy soldiers flung down their weapons and came out shouting, “Kamerad! Kamerad!” About the same time a few intrepid GIs penetrated the enemy stronghold, flinging grenades and firing wildly, but even then many paratroopers held their ground until killed or wounded. Three fanatics continued to fire their machine gun into the flanks and rear of passing GIs and did not stop until Brewer’s blade buried them alive. Now, with Americans building up on Kraut Corner’s eastern flank the position began to crumble and the enemy grudgingly pulled back. The fight for Kraut Corner had taken a precious hour and a half.

Capturing Cloville

While Company E struggled for Kraut Corner, Captain Wallace’s Company F was having considerably better fortune. Having crossed the line of departure at 6:20, the company conducted vigorous attacks on the enemy’s weaker flank and made good progress with the aid of the tanks. By 7:30 they had made contact with the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry to their left and continued a slow but steady advance, battling from one field to the next as heavy artillery paved the way.

The success of Company F was greatly aided when the weapons platoon leader, Lieutenant John Dumont, brought his machine guns up even with the leading squads to provide direct fire support. At one point Dumont’s audacity almost cost him his life. In his zeal to bring his guns forward he had leaped through one hedgerow opening only to discover that he was facing nine enemy paratroopers. Caught off guard he simply commenced screaming at the top of his lungs. The startled Germans immediately threw up their hands in surrender. Dumont later declared, “I was too scared to do anything but yell.”

By 8:20, Company F was already a couple of hundred yards ahead of Company E and receiving sniper fire as it approached Dodge Woods. Captain Wallace sent his 2nd Platoon to clear them out. As these men struggled for Dodge Woods, Lt. Col. Norris became acutely aware of the ever widening gap between his assault companies. Fearing a repeat of the June 16 fiasco, he urged Company E, which was just then closing on Cloville, to step it up so that he would not be forced to commit his reserve.

Cloville, a tiny hamlet of perhaps 10 houses, had been reduced to rubble by the pre-assault bombardment. Company E began its attack at about 8:45 but was again stopped cold by heavy machine-gun fire. Then a self-propelled 88mm assault gun appeared at a road junction west of town, rocked to a halt, and fired. Almost instantaneously the gun of Staff Sergeant Paul Ragan’s tank swung around to meet the behemoth and the duel was on. A second Sherman joined the fray, and the German self-propelled gun was quickly eliminated when Ragan’s gunner slammed home a killing shot. As this vehicle blazed, a German Mark IV tank joined the fight from the shattered village, but Sergeant Ragan’s gunner again zeroed in and repeated his feat. With the armor threat neutralized, the infantry rose up to assault the village. By 11:30 the company command group was occupying the ruins.

While the leading companies ascended the hill, Lt. Col. Norris followed with his forward command group. They had hardly advanced 300 yards when they came under fire from an enemy 75mm self-propelled gun situated near the tiny hamlet of Le Parc to their left. Seven or eight rounds struck the group and inflicted numerous casualties. Among those killed were 1st Lt. Michael Wichrowski of the weapons company and his communications sergeant. Also hit was 1st Lt. Bertrand Warner, commander of Company G, the reserve unit. First Lieutenant Baxter “Lucky” Lawson was then given command of the company, but before he could receive his orders, he too was struck down and command of Company G passed to 2nd Lt. William Harman, its third commander within a matter of minutes. Company G would continue to receive varying amounts of artillery fire as it followed the assault.

About the time Cloville was taken, the cloud cover broke, offering the opportunity for one of the planned P-47 airstrikes, but by noon the clouds had again sealed the sky. Still, a number of aircraft made their sorties only to have one bomb fall near the battalion command post and another close to Company G. Fortunately, there were no casualties, but the airstrikes were hurriedly cancelled for the remainder of the day.

The Fallschirmjäger’s Fighting Retreat

Having secured Cloville, Company E moved into the fields beyond where it finally caught up with Company F, which by then had cleared Dodge Woods. Now the 2nd Battalion advanced as one battle line. Although not yet committed to battle, Company G performed mop-up operations, often resulting in tense standoffs with bypassed enemies. On more than one occasion, GIs peered nervously into the depths of an earthen bunker and called for the occupants to surrender. Often as not the reply would be an extended burst of gunfire followed by a stream of guttural obscenities. The situation was generally resolved when a grenade or two was tossed inside. An exception, however, was Sergeant Wayne Parker who would dive unarmed into a cavernous dugout to drag out a snarling, wounded paratrooper— an incredible feat knowing the fanatical nature of the foe.

With the loss of Kraut Corner, Cloville, and Dodge Woods, the enemy was now forced to conduct a fighting withdrawal. American artillery continued to pummel each successive hedgerow as both companies moved steadily forward, sweating snipers and eliminating last-ditch pockets of resistance. German artillery responded in kind, spraying shrapnel on cringing, frightened soldiers. Battle sounds rose to such a deafening roar that one soldier later remarked that “so much stuff was flying around” that they could not judge the effectiveness of their own mortars.

By then the tank-infantry-engineer teams were again working flawlessly, and by noon the battalion was nearing the crest and preparing to drive the enemy down the reverse slope. At one point Lieutenant Winstead’s platoon was pinned down by machine-gun fire from the right, but within an hour the dilemma was resolved when the frustrated lieutenant simply ordered his men to rise up and charge forward and away from the menacing gun. It worked, and the assault continued. By mid-afternoon the battalion was clearing snipers from the village of Le Soulaire situated midway down the reverse slope. At this time the tanks accompanying Company E ran into increasing antitank fire as well as rough, wooded terrain and were diverted into F Company’s sector where more favorable ground was found.

With the western slope of Hill 192 in American hands enemy resistance broke, and by 5 pm leading elements had reached the battalion objective on the St. Lo-Berigny highway. Private Abraham Kalmikoff, a weapons platoon runner for Company F, sprinted across the road in search of a suitable route for the tanks and was promptly killed by a sniper. At about the same time Staff Sergeant Leonard Katzber and Pfc. Sam Woods, also of Company F, made their crossing. Soon after, men of 2nd Platoon, Company E infiltrated over the highway by ones and twos and by 6:20 pm both companies began to consolidate their gains in and around the junction town of La Calvaire while Company G peeled off to cover the right flank. As the men put their shovels to work, five enemy tanks approached from the direction of St. Lo but were halted by an avalanche of artillery shells. Later, Company E repelled a brief counterattack that also included armor, but when the tanks of the 741st knocked out another self-propelled gun the threat dissipated. By 10 pm, all was relatively quiet.

The 2nd Battalion, 38th Infantry had reached its objective—the only assault battalion to do so that day. The battalion history recorded a loss of two officers and 20 enlisted men killed; eight officers and 150 enlisted men wounded. Enemy casualties were estimated at twice that number.

Tank Support Lost

In the central sector, Lt. Col. Frank Mildren’s 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry jumped off at 6:20 using the Cloville-St. Georges d’Elle road as the line of departure. First Lieutenant Harold Shepherd’s Company C on the right had the mission of crossing the actual peak of Hill 192, while Captain Roy White’s Company A was to take the greater part of Ford Woods, the large diamond-shaped forest that covered much of the reverse slope. As with the 2nd Battalion, the march to the line of departure was contested by infiltrating Germans. Within minutes of jump-off, Medic Lester Robbins of Company A assisted the first of many casualties to the rear. It took more than a half hour to reach the Cloville road.

No sooner had the battalion crossed the line of departure than it was met by withering fire augmented by preregistered mortars and artillery. Within 30 minutes all six tanks in the first wave were hit by antitank weapons. Two were left flaming on the forward slopes, one of which was destroyed when a mortar round fell squarely on the TNT-laden rack on its rear deck. The force of the ensuing explosion knocked the entire turret from the chassis and flung a length of tread high overhead until it wrapped around a tree in Company E’s sector, hundreds of yards to the right.

Other tanks were hit as well, including one that had its main gun damaged and another that struck a mine, and before long the few surviving tanks pulled back. Captain Cecil Thomas of Company A, 741st Tank Battalion reported to his commander that not only had he lost a good number of tanks but that the surviving ones could not maneuver over the rough, muddy terrain. Colonel Skaggs gave Thomas permission to find a different route to the top, and the tanks lumbered off to the right, leaving the infantry on its own.

Stripped of tank support, each company was forced to conduct brutal frontal attacks against each hedgerow, the same old tactic that had proved so costly in the past. After taking several fields, the leading elements of Company A were brought to a standstill by intense fire emanating from a three-sided defense centered on a group of four fields occupied by at least two platoons of paratroopers. Time and again soldiers closed in only to be driven back by automatic weapon and rifle fire supplemented by rockets. Mortars pounded the fortress as another assault surged forward, covered by automatic weapons. The staccato hammering of machine guns was answered by the rapid buzzsaw rip of German weapons, and again the attack faltered. Eventually, all three platoons were committed, but without tank support the situation seemed hopeless. By 9 am, the company had lost so many men that it was deemed combat ineffective.

The Fighting for Ford Woods

While Company A battled for this stubborn position, Company C to the right faced lighter opposition and had pushed its attack farther up the hill. By 11 am, the company had distanced itself from Company A by some 150 yards, presenting the Germans an enticing open flank. Almost immediately, heavy machine-gun fire ripped from the four-field strongpoint with predictable results. Again, a vexing situation developed. Desperate to plug the gap, Mildren committed his reserve, but through miscommunication Company B crossed into the zone of Company A, causing confusion. As fortune would have it, the Germans holding the four-field strongpoint believed they were being outflanked and pulled out. Upon occupying the fortress, the GIs found the position littered with many corpses and abandoned weapons and equipment.

By then, casualties in the assault companies had become so heavy that the medics of the 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry were sent to assist in the removal of the wounded. One of these, John Gill, recalled how his four-man team had to make heart-wrenching decisions as to who to evacuate and who to leave to die. At one point Gill’s litter team had carried one bloody soldier halfway down the hill when he died, so they unceremoniously dumped the body and returned for other wounded.

With Company A shot up, Company B assumed the lead on the 1st Battalion’s left. By 1:30 they were in Ford Woods, now smoldering and denuded of much of its foliage by the intense artillery bombardment. Still, strong opposition was feared, so a skirmish line was formed to sweep through the forest’s western half.

Meanwhile, Captain Thomas of the attached tank company had found an alternative route for his remaining Shermans and joined Company C between Dodge and Ford Woods on the right. Now the engineers resumed blowing gaps in the hedgerows and again tanks surged forward with all guns blazing. With the resumption of the tank-infantry-engineer tactics, the right wing of Company C reached the hilltop against moderate resistance. At the same time, the company’s left wing cautiously entered the extreme western portion of Ford Woods.

By mid-afternoon the entire battalion was moving through the forest of the reverse slope with the depleted Company A now trailing. Fortunately, because of the severe pounding by artillery only a few snipers were encountered and systematically eliminated, but when the leading elements emerged from the shattered tree line resistance again stiffened and things began to bog down. General Robertson cautioned Mildren that daylight was running short and ordered him to step it up, but by 7 pm the battalion had barely advanced beyond the tree line. At that time the order was given to “button up.” Although Mildren’s men had secured the coveted peak of Hill 192, the rifle companies remained 200 yards short of their objective of the St. Lo-Berigny highway.

“Purple Heart Draw”

The far left wing was assigned to Lt. Col. John M. Hightower’s 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry, tasked with traversing the easternmost slope of the hill. As with the 38th Infantry, the line of departure would be the Cloville-St. Georges d’Elle road. The chief obstacle here was a deep draw situated anywhere from 200 to 400 yards from the line of departure, running east to west for several hundred yards with banks so steep that it would be a barrier for the tanks of Company C, 741st Tank Battalion. Well covered by preregistered mortar and artillery concentrations as well as cross-firing machine guns, it would soon be referred to as “Purple Heart Draw.”

At 6 am, the infantry moved forward following a rolling barrage while the tank-engineer teams blasted through the first tier of hedgerows. After pushing the enemy from two or three fields, Captain Porteous’s Company A on the left came upon the draw. As the men of 1st Platoon scrambled into its depths they were sickened by the sight of a number of bloated corpses of comrades who had fallen in previous actions. The four accompanying tanks, under the command of Staff Sergeant Malcolm Reynolds, wisely avoided the steep bank, opting instead to spread out along its northern rim to provide covering fire.

The moment the infantrymen reached the bottom of the draw, the enemy unleashed hell on earth. Artillery and mortar shells plunged with a vengeance while several machine guns cut loose with murderous fire from a pair of houses overlooking the draw to their left, joined by another gun concealed at a nearby bridge that spanned the gorge. Other machine guns swept the vale from the opposite bank, raking the hapless soldiers with perfect crossfire. Officers rallied men who put up a great deal of return fire but were beaten down. The 1st Platoon was trapped.

Sensing disaster, Captain Porteous sent his 2nd Platoon hooking around through several fields to the right in an effort to flank the draw from the south. A pair of tanks accompanied the maneuver with the additional mission of blasting the menacing houses near the bridge, adding their firepower to that of the four tanks that remained above the draw’s northern bank. Meanwhile, the beleaguered souls in the gully’s sump continued to sustain casualties at an alarming rate.

The flanking attack inched forward but eventually stalled amid thumping mortars and the searing rip of machine guns. Frustrated, Porteous threw in his reserve platoon, the 3rd, on a route that traced that of the 2nd to press the attack. With this added pressure the two accompanying tanks pushed forward while 88mm shells screamed all around them. Eventually, each ground to a halt within 30 yards of the troublesome houses and fired point blank with their 75s, crumbling the walls. That seemed to do the trick. At about the same time the enemy noted the advance of 3rd Platoon as well as the fact that Company C farther to the west was gaining ground, threatening their left flank. Realizing that their defense was compromised, the Germans reluctantly withdrew a field or two under cover of a delaying force.

By the time the draw was cleared, Company A had suffered severe casualties, yet had barely advanced from 300 to 400 yards. All but 13 men of the 1st Platoon were killed or wounded, including the platoon leader and platoon sergeant. The objective was still well over 1,000 yards away, and it promised to be a very long and difficult day.

Infantrymen Taking Initiative

While all this occurred, Company L, 23rd Infantry conducted a hard-fought limited objective attack to gain one to two hedgerows beyond St. Georges d’Elle. Due to the patchwork terrain, the 2nd Platoon advanced one hedgerow farther than the right platoon and was exposed to flanking machine-gun fire. Ten men of the two assault squads were mowed down by a single machine gun. Furthermore, a platoon of Company I had the mission of protecting the 1st Battalion’s left flank and was all but annihilated moving the 300 yards from the church at St. Georges d’Elle toward the bridge. Despite the cost, these actions kept the Germans from shifting forces to assist those defending the hill.

While Company A was coping with disaster, Lieutenant Vere McClement’s Company C on the right, aided by the tank-engineer teams, was having appreciably better success since resistance in this sector was less severe. Still, there were numerous spirited actions. In one instance, Sergeant Clem Turpin had machine-gun bullets slashing between his prone body and the earth. When he was finally able to rise, he discovered that while he remained unscathed his cartridge belt had been shredded. Later, after a heated exchange of gunfire, Turpin captured the crew of an antitank gun and then turned the weapon to fire five rounds at an enemy position farther up the hill. Elsewhere, several enterprising soldiers put their rifle grenades to good use when they twice managed to loft fragmentation grenades into the treetops above stubborn machine-gun nests. The explosions rained steel fragments on the gunners, mimicking the effects of tree bursts. Such actions contributed greatly to the company’s success.

For a while, C Company’s advance was hampered by lack of contact with the 1st Battalion, 38th Infantry to its right. Fearing an open flank, the company held up until contact could be regained. Once established, the attack continued with much more confidence. About noon, the attached tanks approached a house near Ford Woods where the Americans discovered a Mark IV tank lying in ambush from a sunken road. Fortunately, a pair of steel-nerved riflemen crept along the hedgerow opposite the tank and peeked over its crest. The tank commander was standing in the open turret with his back to them. Both sneaked up with grenades ready. One shot the commander. Then both pitched their bombs down the open hatch, followed by two more. The ensuing explosions destroyed the tank.

No-Quarter-Asked, No-Quarter-Given

Meanwhile, things remained in a state of confusion back at the draw. In the course of neutralizing the German strongpoints on the left flank, all three platoons of Company A were now facing east. The attack was supposed to be toward the south and over the hill to the St. Lo highway. After a great deal of radio communication and map consulting, the situation was rectified and the attack resumed. Initially, there was concern over the loss of platoon leaders in both the 1st and 3rd Platoons, but fortunately Sergeant William Stanley of the 3rd Platoon managed to integrate the remnants of the decimated 1st Platoon into his own. Once organized, he pushed them halfway to their objective, often under heavy mortar fire. At one point Stanley was so fired up that he radioed back that he was not going to stop until he reached Berlin! Such was the spirit of assault in the 2nd Infantry Division.

Still, every step of the attack was vigorously contested. Lt. Col. Hightower became so disturbed by the slow progress of his battalion that he eventually committed his reserve, Company B, which swung out on the battalion right to sweep through the eastern point of Ford Woods.

As the GIs gradually gained the upper hand, the enemy resorted to blatant treachery. On one occasion, a group of about 25 paratroopers waved a white flag as they approached the left flank of Company A. Suddenly, they dropped the flag and dashed into a nearby farmhouse from which they continued the fight. Angered by the ruse, the Americans called artillery on them, but the paratroopers held out for the remainder of the day, only withdrawing under cover of darkness. Other truces were attempted elsewhere, but the wary men of the 23rd Infantry would have none of it.

Earlier, when the heavy losses in Company A were realized, the regimental commander, Colonel Jay Loveless, ordered elements of his 2nd Battalion forward at noon to continue the attack on the left. However, it was nearly 5 pm by the time this force reached the battlefront, almost too late to be of appreciable assistance. Still, Captain George Duckworth of Company F noted that when the attached tanks smashed through a hedgerow the enemy, though dazed by the incessant bombardment, came out full of fight. “It was a fierce, no-quarter-asked, no-quarter-given battle,” he recalled, “often man-to-man with rifle butts, bayonets, and trench knives.”

By then darkness was fast approaching, and soon all offensive operations ceased. Although the 1st Battalion, 23rd Infantry had conquered its assigned section of Hill 192 with a gain of 1,500 yards, it too fell short of its objective. The exhausted soldiers dug in along a road that ran diagonally northeast from the eastern tip of Ford Woods to St. Georges d’Elle, facing a sizable pocket of defiant paratroopers. The battalion’s ultimate goal, the St. Lo-Berigny highway, remained some 400 yards beyond its reach.

Having lost their lofty observation post of Hill 192, the Germans withdrew that evening to the south side of the highway and immediately began preparing for the next assault. The following day, July 12, both of the American battalions that had halted on the reverse slope continued their attacks against mild resistance and were soon across the St. Lo highway where they dug in with the enemy again only one or two fields away. The Battle for Hill 192 was officially over.

40,000 Casualties For 7 Miles Gained

The Germans had suffered mightily during the July 11 assault. One cannot discount the effects of the preliminary bombardment or the barrages that preceded each phase of the attack. A surviving German paratrooper later wrote: “When one hears for hours the whining, whistling, and bursting of shells and the moaning of the wounded, one does not feel too well. Altogether it was hell.”

The American artillery had dropped more than 20,000 shells on the hill. Still the Germans emerged to man their posts and fought tenaciously. The 3rd Battalion, 9th Parachute Regiment on the western slope and the 1st Battalion, 5th Parachute Regiment on the eastern slope bore the brunt of the attack and were decimated—losses that could scarcely be replaced. It was reported that the commander of the 9th Parachute Regiment wept when he learned of his losses. In the course of the battle, the two defending battalions were reinforced by the 12th Parachute Gun Brigade and the 3rd Parachute Reconnaissance Company. As the men of the Indianhead Division gained ground the Germans tossed in the 3rd Parachute Engineer Battalion as a last resort, but all for naught.

For the Americans it had been a strenuous but extremely successful operation. Casualties had been fewer than anticipated: 69 killed, 328 wounded, and eight missing. Prior to this day the division had suffered many times that number in two previous attempts to take the hill, not to mention those lost on the many raids and reconnaissance patrols that had scoured the forward slopes.

With Hill 192 now in American hands, the stage was set for the capture of coveted St. Lo the following week, ending 17 days of grueling combat that had cost the First Army 40,000 casualties for a gain of seven paltry miles. Seven days after the fall of St. Lo, Operation Cobra was launched, unleashing the armor of Lt. Gen. George S. Patton’s Third Army on its whirlwind drive through France. Within four weeks the Allies were in Paris. The Normandy stalemate had been broken. The hated hedgerows were now nothing more than a bad memory.

Great article. I’m using it to attempy a computer sim of Hill192 using Battlefront’s Combat Mission Normany campaign.

You picture of a German Fallschirmjaeger preparing ammunition should indicate the weapons seem to be all captured US Bazookas and MG’s including water cooled MG’s.

Ed

My great uncle was a 1st Lieutenant in the 23rd Company A that died on July 12th 1944. Reading through the battle, it sounds that he was most likely involved in the area around purple heart draw. Could he have been the platoon leader mentioned as a casualty on the 11th at purple heart draw? Is there any information as to troop movements on July 12?