By Glenn Barnett

The first Allied victory of World War I occurred when Australian volunteers occupied the German colony of northeastern New Guinea and the adjoining Admiralty Islands. After the war, the League of Nations confirmed Australia’s possession of these lands as a mandated territory.

Ominously, the German Micronesian islands to the north of New Guinea were occupied by Japan. Like Australia, Japan was given a League of Nations mandate over its wartime conquests. During the interwar period the Japanese illegally built up naval and air bases on these islands.

When war began in Europe in September 1939, great demands were placed upon Australia, which at the time had no army to speak of. The Australian Imperial Forces (AIF) was formed to support Great Britain in Europe and North Africa. Other rapidly conscripted forces went to the British in Malaya, the Dutch in Indonesia, and the French in New Caledonia. Australian resources were stretched thin. Yet the direct threat from Japan had to be taken seriously.

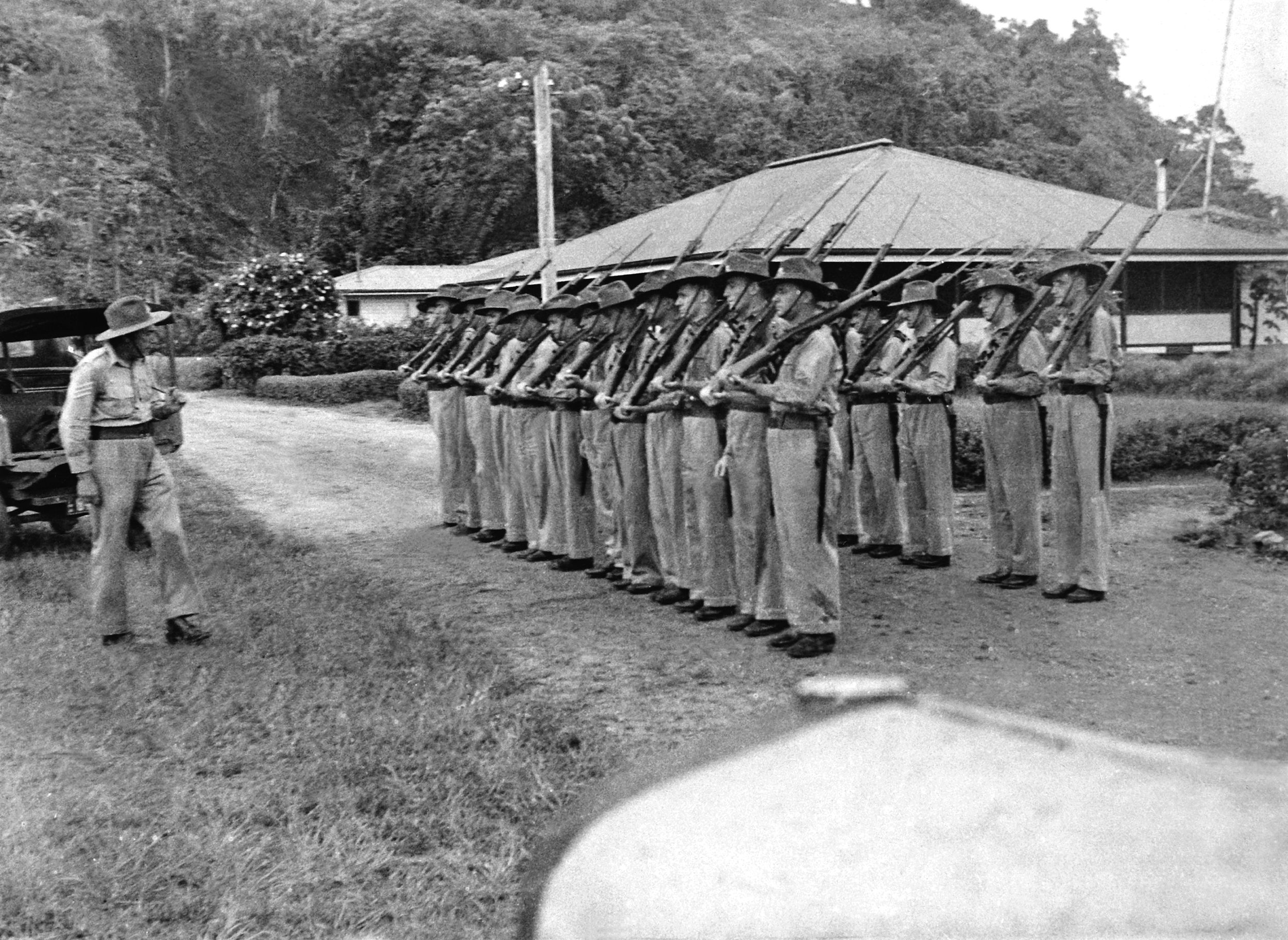

Late in 1939, the New Guinea territories were authorized to raise their own civilian militia to consist initially of 21 officers and 450 men. This force was to become known as the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles (NGVR). Their charter was limited to providing “beach defense against raiders.”

For the next two years the NGVR attempted to organize its civilian volunteers into effective military units but faced the difficulty of individual job relocations and recruitment efforts by the AIF, which took many able-bodied men into the regular army. Another logistical difficulty was that the NGVR was divided into five or six different locations based on towns in New Guinea, New Britain, and New Ireland, each separated by hundreds of miles of jungle or ocean.

The largest contingent was based at the mandate’s capital of Rabaul on New Britain. In 1940 Rabaul had a mixed Australian and expatriate European population of about 1,200 people, the largest in the New Guinea mandate.

The rest of Rabaul’s population consisted of 1,300 Asians, mostly Chinese, who were also worried about the Japanese threat. Some of these were organized into an ambulance corps. The 70,000 indigenous people on the island were excluded from military service. The German experience with native soldiers had not been good, and, besides, it was Australia’s job to protect them, not to expose them to danger.

Rabaul was a strategic prize. The crescent city wrapped around a volcanically created deepwater port sheltered on three sides. It was one of the best natural harbors in the Pacific. The 200 or so original NGVR recruits at Rabaul were provided with a few World War I- era weapons: rifles, bayonets, .303-inch (7.7mm) machine guns, and a few light mortars. One supply shipment brought a consignment of wool greatcoats, a useless item in the humid tropics. Some of the tinned meat they received as rations dated from 1918 and were spoiled. Peacetime budgets kept them undermanned and underarmed. If a civilian volunteer wanted a uniform, he had it made by local Chinese tailors at his own expense.

This was the state of things at Rabaul in March 1941, when the Australian Army ordered the 2/22 battalion, called Lark Force, to defend the town and the island of New Britain. By the time the war in the Pacific started in December, there were 1,400 regular Australian troops in Rabaul under the command of Colonel J.J. “Joe” Scanlon. The men of the 2/22 paid little attention to the civilian-based NGVR who worked at their jobs during the day and drilled at night. Nor did they take advantage of the militia’s experience and knowledge of the terrain and the local population.

Scanlon had his orders. He was to defend beach landing sites, the airport, and the port facilities of Rabaul. Those orders were never altered to meet changing conditions.

Among the equipment the 2/22 brought with them were two six-inch coastal defense guns, which were placed at the mouth of the harbor. Several World War I-era 3-inch antiaircraft guns were also situated. Early in December, the 24th Air Recognizance Squadron showed up with four Lockheed Hudson bombers, two or three Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats, and 10 new Commonwealth Air Corporation Wirraway trainer-fighters.

The Wirraway was the first warplane built in Australia. It was produced under license from North American Aircraft and was based on the same design as that of the American T-6 Texan trainer. The Australians outfitted their version with two machine guns (7.7mm) and bomb racks. The Wirraway was slow and awkward. It was totally outclassed by Japanese planes. Circumstances, however, required it to be a frontline fighter.

When war broke out, the government in Sydney authorized the evacuation of women and children from New Guinea and New Britain. Government employees and administrators were not allowed to evacuate. For them, it was business as usual until it was too late.

On Christmas Day, a single Japanese four-engine bomber flew over Rabaul on reconnaissance. The first air raid occurred on January 4, 1942. Eighteen twin-engine bombers dropped their bombs on the city’s two airfields while antiaircraft fire exploded impotently 5,000 feet below them. Two Wirraways were scrambled, but to no avail. Bombing became a near daily event.

Colonel Scanlon of Lark Force soon realized that he would not be reinforced. Australia was stretched to the limit of its manpower capacity, and no more help would be forthcoming. It began to dawn on everyone in Rabaul, so far from Sydney, that they were expendable.

On January 19, a coast watcher reported two aircraft carriers, four cruisers, and several destroyers escorting a troop convoy. They were headed for Rabaul. Only now did the military authorities call up the 80 or so NGVR who remained in the city and assign them to defend portions of the beach.

The next day an air armada of 80 Japanese bombers and 40 escorting Zero fighters roared over Rabaul. Six Wirraways bravely went up to meet them, and all were shot down. The bombers hit the wharves, shipping, and the town itself. Following the raid, the remaining men of the 24th Squadron decided to leave Rabaul. They boarded their remaining planes and departed. For the 2/22 and the NGVR there was no way out.

The departing aviators blew up the remaining ordnance at the airport. When the bombs were detonated, the explosion damaged some nearby houses and knocked out the wireless radio tower, the only communication link with mainland Australia.

Just after dawn on January 23, the Japanese invasion began. An estimated 5,300 Japanese troops were involved in the landings. The men of the NGVR were assigned to defend their position on the beach.

There was some initial success at the landing sites. Japanese soldiers were mowed down in the surf by the machine guns and mortars of the defenders. Soon, however, Japanese firepower overwhelmed the defenders who were running low on ammunition. Japanese losses came to only 16 killed and 49 wounded with the loss of one bomber and crew.

The Australians fled inland, but they had made no provision for a second line of defense. There was no rendezvous point; no supplies had been moved to the area, and there was no apparent leadership. Individually and in groups, the defenders either gave themselves up or fled into the interior hoping for rescue. The 2/22 ceased to exist as a fighting force.

In January 1942, it was not yet understood how brutal the Japanese would be in victory. Those who sought to surrender could not guess the fate that awaited them. After the war, the bodies of 158 soldiers, civilians, and missionaries were found at the Tol Plantation where prisoners had their hands tied behind their backs with fishing line and were taken into the bush where they were bayoneted or shot.

On nearby New Ireland, a small company of about 160 officers and men of the 1st Australian Independent Company and a few former NGVRs could not hold off some 4,000 Japanese troops who landed there at the same time as the Rabaul attack. Rather than defend the beaches, the Australians retreated inland. In their haste they forgot to destroy important stores. Five hundred drums of aviation fuel, oil lubricants, and quantities of food fell into Japanese hands. Sixty civilians and surrendering soldiers were executed there.

This was not the fate of most of the two garrisons. The majority of the soldiers taken were interned until June when the 7,267-ton Japanese passenger ship Montevideo Maru put into Rabaul. The Japanese rounded up 1,035 men, mostly of the 2/22, and 36 members of the NGVR (others may have been listed as civilians) and forced them into the hold of the ship, which sailed westward toward the Philippines. Its likely destination was the prison camps of Burma.

Fate intervened, however. Off the coast of Luzon on July 1, the Montevideo Maru was spotted by the submarine USS Sturgeon. The sub’s captain had no way of knowing the nature of his victim’s cargo. The Sturgeon attacked. All of the Australians, locked below decks, went down with the ship. It was the worst maritime disaster in Australian history.

Back on New Britain, some of the NGVR and 2/22 men did not surrender. Forced from the beaches, they blundered into the jungle where many of them came down with tropical diseases such as malaria and typhoid. Sick, hungry, and lost, the frightened men dared not give themselves up. It was then that the NGVR on the mainland of New Guinea came into its own.

Between them, Lt. Cmdr. Eric Feldt of the Royal Australian Navy and Lt. Col. Keith McCarthy cooked up an impromptu plan to rescue as many men as possible from the disaster on New Britain. McCarthy, operating from a secret location a little south of Rabaul, had a still-working wireless transmitter. He coordinated operations with Feldt, who was in New Guinea. Feldt was the director of the coast watchers and at the hub of their communications.

To effect the rescue, the NGVR needed the help of Christian missionaries. The mission stations on New Guinea had powerful radio transmitters, sheltered ports, and, most important, boats. Several mission workers took up arms with the NGVR and manned the boats, even while their missions were being bombed. Several small boats made off for New Britain under the cover of darkness to conduct an evacuation. Sick, wounded, and exhausted men made their way to small landing sites as yet unnoticed by the Japanese to embark for New Guinea or Australia. Some 214 men were saved.

When some of the NGVR men reached Australia they were treated with suspicion by the military authorities because they wore odd uniforms with unrecognizable patches. Few in Australia knew of the existence of the NGVR.

With Rabaul lost to the enemy, the military authorities in Sydney finally realized the importance of the NGVR. Urgent telegrams reached the scattered and desperately few men in New Guinea, ordering them to prevent the Japanese from landing on the coast. Without proper arms or equipment it was an impossible task.

Resistance to the Japanese in New Guinea centered around the Huon Gulf on the northeast coast. Major W.M. Edwards was now in command of the NGVR. It was a greatly reduced force. So many able-bodied men had joined the AIF that his own militia was more like a home guard of determined if aging men.

At noon on January 21, waves of Japanese bombers and fighters roared over the twin towns of Lae and Salamaua on the Huon Gulf coast. That afternoon the civilian population of Lae was moved to an emergency camp inland. The NGVR assisted the civilians, both European and Chinese, to evacuate and for the next several days combed the town for supplies and equipment ahead of the inevitable invasion. They destroyed anything that could be of use to the enemy.

The NGVR base of operations moved inland to a prewar center for gold mining in the Bulolo Valley behind the coast of Salamaua and the Markham Valley behind Lae. The rough and tumble gold miners flocked to the NGVR, which needed all the manpower it could find. In addition to military duties, the NGVR was the de facto civilian authority as well. The civil office had broken down, and the Volunteer Rifle officers were the last vestige of Australian authority on the northeast coast of New Guinea.

The Japanese did not come right away, and the small detachments remaining in Lae and Salamaua continued the job of gathering supplies and sabotaging material that might be of use to the enemy. About 20 NGVR men stayed in Salamaua where they performed useful work at the little airstrip. They refueled short-range Hudson bombers flying from Port Moresby on reconnaissance or bombing raids against Japanese positions at Rabaul. Using 44-gallon drums of aviation fuel and pumping by hand, they extended the range of the Hudsons and helped them make it back home.

In the predawn darkness of March 8, Private Jim Keenan was on watch at Salamaua. Looking out to sea, Keenan was not sure what to make of the dim forms he was seeing at the periphery of his vision. He woke his mates in their tents just in time to see Japanese landing barges making their way through the surf. The little garrison sprang into action. They coaxed an old truck into starting and rushed to the airstrip to set fire to the fuel dump, destroy the wireless tower, and make their way to a wire footbridge and safety across the Francisco River.

The bridge wires were cut just as an advance troop of Japanese scouts reached the opposite bank of the river. Each side took pot shots at the other, but there were no casualties. That same morning the Japanese landed at Lae. About 3,000 Japanese troops took part in the dual assaults.

One soldier of the Salamaua squad buried four cases of rum for the day when the Australians would return. When that day came on September 13, 1943, the soldier and his mates made a beeline for the spot only to find a Japanese antiaircraft gun mounted on 47 inches of cement on top of their buried treasure.

Approximately 1,800 Japanese soldiers were garrisoning Lae, with another 300 at Salamaua. To face them, the NGVR could field just over 100 trained and fit men. There were perhaps 200 more who could not travel over the mountainous jungle paths to fight owing to wounds or disease. Still, the military authorities in Australia expected them to engage the Japanese. In the anxious days before the Battle of the Coral Sea, there was nothing to spare for the remote outposts in northern New Guinea.

The desperate authorities in Port Moresby continued to send messages to Major Edwards, ordering him to prevent the Japanese from moving south overland. Edwards knew these expectations were impossible for men who had only a few rifles and Vickers machine guns. Many of the men were barefoot, their uniforms well worn. There was no proper medical attention available and no resupply.

Edwards put on a display of bravado to make the enemy think that he had larger numbers than he did. Raids of two or three men, frequently repeated, gave the Japanese the impression that they faced a much larger force. In any event the enemy did not venture inland until it was too late. From January until June, the NGVR soldiers were the gatekeepers who prevented the Japanese from moving overland through the gold fields and south to Port Moresby.

One of the most important tasks undertaken by the NGVR was to report on Japanese activity at Lae and Salamaua. They knew the lay of the land and could establish vantage points on hills and even in trees to spy on the enemy below. Useful intelligence about Japanese movement on land, at sea, and in the air was transmitted to Port Moresby. The Japanese knew they were there and sometimes made them the object of patrols. There were casualties on both sides.

In June, following the important victory in the Battle of the Coral Sea, the Australian government finally felt it could spare some troops to reinforce the ragged remnants of the NGVR. The 2/5 Independent Company began arriving by air. Detachments of the 300 men of the 2/5 were dispatched throughout the Bulolo and Markham Valleys.

NGVR member Bob Emery remembered, “Early June, I think it was. The 2/5th Independent Company started moving down our way, and this cheered us up quite a bit because it looked like we might get a bit of help. We see these young blokes with all this new equipment … new boots, new rifles, Tommy guns and everything you could think of.”

The NGVR and the 2/5 were gradually combined into Kanga Force. Lt. Col. N.L. Fleay, the commander of Kanga Force, was eager for action. The NGVR had long scouted the enemy at Salamaua and knew the Japanese positions, routines, and daily activities. Now with the modern weapons and the fresh manpower of the 2/5, they could strike.

It would be June 29 before men and equipment could be moved into position for a raid on Salamaua. Twenty-one NGVR joined 50 of the 2/5th. They were divided into seven teams to attack five Japanese strongpoints.

Acting independently, the teams made their way in the darkness to their assigned targets. Barking dogs and alert sentries awakened the Japanese and caused the attack to go off prematurely. The Japanese poured out of their shelters and returned fire in the dark. Still, the raiders estimated that they inflicted over 100 casualties on the enemy for a loss of four wounded. The little raid at Salamaua inflicted the first defeat upon the Japanese Army since the beginning of the war in the Pacific. In Australia the press had a field day.

The next night a raid was made on a forward Japanese position in a plantation outside Lae. The object was to destroy a field gun, blow up a bridge to prevent reinforcements, capture documents, and kill as many of the enemy as possible.

The attack on Salamaua the night before alerted the Japanese, and they were ready. It was a moonlit night, and the attack was delayed until 2 am, when a mist settled over the area. Once again barking dogs alerted the Japanese to danger. The attack on the bridge and gun were abandoned, and the raid became a shooting match. Major T.P. Kneen was one of the first Australian casualties. With the loss of their leader, the Australians gradually withdrew. For the cost of one dead and two wounded they claimed over 40 enemy casualties.

The Japanese increased their patrols, and casualties mounted on both sides. Increased enemy air activity frightened native carriers away, and portage became a real problem.

On July 21, the Japanese began putting troops ashore at Buna and Gona for a march over the Owen Stanley Mountains toward Port Moresby. Once again, messages urging action against the enemy reached the men of the NGVR and the newly arrived 2/5th. Once more supplies would not be forthcoming.

While Port Moresby was feeling the pressure of the Japanese push over the Kokoda Trail, some resourceful NGVR men made a 100-mile hike to unoccupied Madang, where they rounded up a herd of 40-50 inbred Zebu cattle left over from the German era and herded them over the mountains to feed the men. But other supplies, especially medical equipment and malaria pills, were not getting through. By the end of August, 2/5 Company was down to 182 men fit for duty. Sickness, chiefly malaria, had taken a heavy toll.

Lieutenant Colonel Fleay was feeling the exhaustion as well. On August 30, as the result of faulty intelligence, he ordered the campsites and towns of the Bulolo Valley to be burned. Kanga Force was to retreat farther inland. He thought a Japanese advance or parachute assault was in the making. The hasty decision caused panic. As explosives were set off, the native carriers deserted their loads and fled.

As it turned out, the enemy was only patrolling, but the homes and businesses of the NGVR men as well as ammunition and stores were burned to the ground. Important bridges were destroyed. This caused some real bitterness between Fleay and his allies. Some NGVR men refused to follow his orders, and he had them arrested. The native people of the area saw some of their settlements burned as well, and much goodwill was lost.

Fortunately, not all of the Australians fled. Two patrols of 29 and 20 men, respectively, remained in contact with the enemy, who had managed to reach inland from Salamaua as far as Mubo. These patrols concluded that the Japanese were settling in and not planning to advance farther inland. The threat was over, but the damage was done.

Other towns on the north coast of New Guinea faced peril. At Madang, fewer than 20 NGVR men had been given rudimentary military training. In August 1941, three NGVR men were sent to garrison the airstrip. The three men were armed with an old Lewis gun, which could swivel skyward. It was all the NGVR could muster for an antiaircraft gun. War work at Madang included setting temporary obstacles on the airstrip that could be removed if a friendly plane approached.

Command of the tiny NGVR force fell to store manager Gordon Russell. Unlike Colonel Scanlon at Rabaul, Russell planned meticulously for a withdrawal. Using local prison inmates, he had food and supply dumps set up a day’s journey apart in the interior. He also took it upon himself to get civilians out of harm’s way. A sea voyage was too dangerous in Japanese-controlled waters. The Australian Air Force refused to fly transports to the north coast because of Japanese air superiority.

Evacuees had to walk overland as far as the 5,500-foot Mount Hagen and continue on foot over the trackless mountains to Port Moresby. Though Madang was bombed on January 21 along with Lae and Salamaua, it was not invaded until November 1942.

Farther up the coast was the town of Wewak. Evacuation from there was complicated by a deranged civil servant named George Ellis. Considered by his peers to be mentally unstable, Ellis ruled his part of the nearby Sepek River like a feudal lord. When civil authorities tried to remove him, he sent his native policemen on a rampage to kill white settlers. Several died in the native police uprising. Eventually deserted by everyone, Ellis took his own life.

European evacuees had to make their way upriver past the carnage on the shore to a safe landing and hike inland to Mount Hagen. There the aged and sick were met by an angel of mercy. A Catholic mission priest named Father John Glover was a former member of the NGVR. His contribution was to fly the mission biplane to lift evacuees off Mount Hagan and to safety at Port Moresby. When his plane crashed, he and a mechanic repaired a second plane and continued the work. When the second plane crashed, Father Glover made his way to Australia and convinced Qantas Airlines to continue the evacuation. Seventy-eight evacuees were rescued, including 18 survivors from the 2/22 at Rabaul.

By October, the main Japanese thrust against Port Moresby over the Kokoda Trail had stalled, and the Allies had assumed the offensive. Men could now be spared to support the NGVR and 2/5 still fighting at Wau. The 300 men of the 2/7 Independent Company were flown into the Bulolo Valley. They were shocked at what they found.

Captain E.W. Stout, the medical officer of the 2/7, wrote about the survivors of 2/5 and NGVR: “The general health of the troops in this area is rapidly deteriorating due to an inadequate diet … not only inadequate but unbalanced, and the constant tinned meat is resulting in a high percentage of gastritis and diarrhea…. Troops are becoming desperately short (of clothing). Clothes are saturated with sweat and dirt each day … Inability to change into dry clothes is causing an epidemic of contagious skin troubles.”

The few remaining NGVR men continued to scout and guide the raids on Japanese positions. Their ongoing observations had located the site of every Japanese machine-gun nest and supply dump and determined the daily routines of the enemy. The main thrust of the war in New Guinea was now out of their hands, but the few NGVR men who remained would serve as coast watchers or guides for American and Australian landings to retake the villages and islands that they knew so well.

During a reconnaissance in force of Los Negros Island in the spring of 1944, American troops were so impressed with the assistance of two NGVR personnel that the NGVR were awarded a Presidential Unit Citation for their contribution, the only Australian militia unit so honored.

Glenn Barnett is a historian and author living in Los Angeles. His father served with the U.S. 32nd Division in New Guinea.

Join The Conversation

Comments