By Arnold Blumberg

During the evening of September 20,1863, the following message reached Washington and was given to the president of the United States: “We have met with a serious disaster; extent not yet ascertained. Enemy overwhelmed us, drove our right, pierced our center, and scattered troops everywhere. Thomas, who had seven divisions, remained intact at last news. Granger, with two brigades had gone to support Thomas. Every available reserve was used when the men stampeded. Burnside will be notified of the state of things at once, and you will be informed. Troops [Confederate] from Charleston, Florida, Virginia, and all along the seaboard are found among the prisoners. It seems that every available man was thrown against us.”

The author of this gloomy telegram was Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans, commander of the Federal Army of the Cumberland. His missive was the first report sent by him to his civilian superiors regarding the defeat of his army at the Battle of Chickamauga. But even before Rosecrans’ rather passive announcement had been sent, the authorities back east had received a much more graphic account of the recent Union military setback. Sent by Charles A. Dana an hour before the Army commander wired his first news of the battle, it was highlighted with such phrases as “Chickamauga is as fatal a name in our history as Bull Run…. Our soldiers turned and fled. It was wholesale panic. Vain were the attempts to rally them. Our wounded are all left behind…. Enemy not yet arrived before Chattanooga.”

A “Bird of Evil Omen”

Of the two preliminary statements, those of Rosecrans and Dana, concerning the fight of September 19-20 outside Chattanooga, Tenn., the latter was given more attention and credibility. Charles A. Dana, a former managing editor for Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, had found favor with the secretary of war, Edwin M. Stanton, early in the national conflict. A supportive editorial Dana had penned in 1862 when Stanton was appointed to the War Department earned the out-of-work newspaperman (he had been forced to resign from the Tribune that same year) first a job as Stanton’s personal aide, and then his assistant secretary of war from 1863 to 1865. As such he was used as what had been termed during the French Revolution a Representative of the People on Mission, or in the future Stalinist Russia, the People’s Commissar. And like his French and Soviet equivalents, Dana roved from Union army to Union army—first U.S. Grant’s and then Rosecrans’, to keep tabs on the officers assigned therein. Regarded as a “bird of evil omen” by the Northern officer corps, the assistant secretary could make or break a soldier’s career by the simple use of a pen or telegram.

Having an informer at his headquarters was bad enough, but Rosecrans was unaware of the animosity held toward him by Secretary of War Stanton. Dating back to early 1862 when Rosecrans dared to advise the self-assured secretary on matters of national military strategy, and continuing during the former’s middle-Tennessee campaign of 1863, Stanton developed such a loathing for the Army commander that he looked forward to any opportunity to remove him from leadership of the Army of the Cumberland. The loss at Chickamauga, and a bold Confederate cavalry raid thereafter—all underpinned by Dana’s increasingly scathing opinion of Rosecrans’ fitness to lead any friendly military force—would give Stanton his chance.

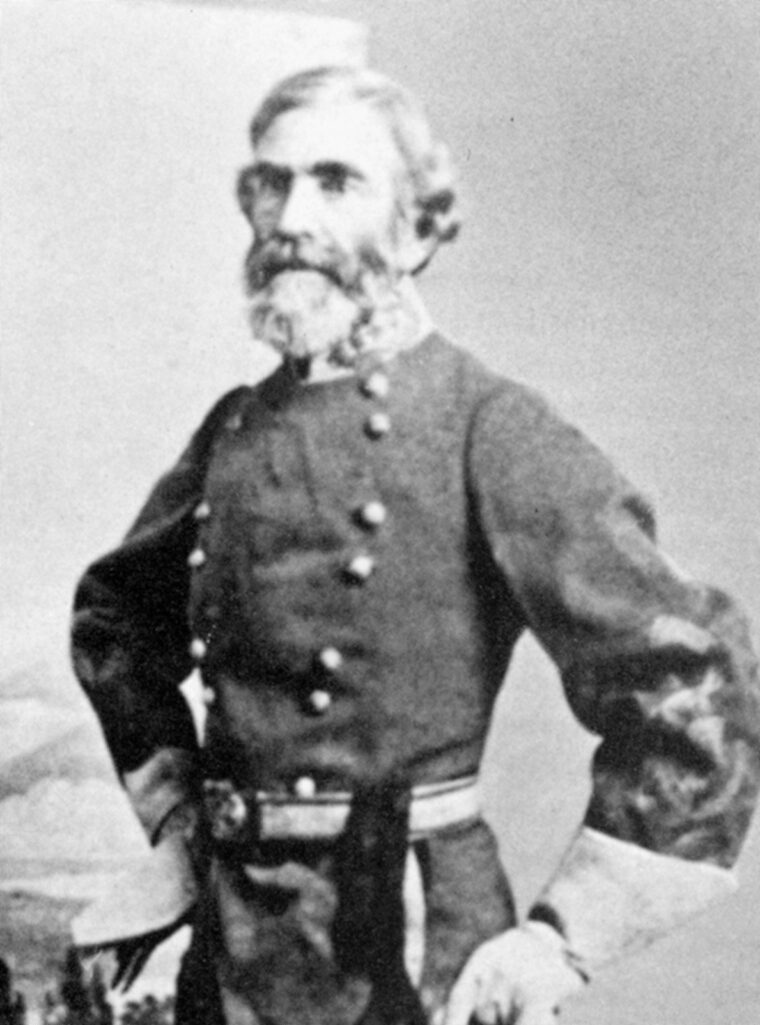

By nightfall of September 20, 1863, the last remnants of the once ever-victorious Army of the Cumberland, now reduced to about 35,000 effectives (from an original force of 58,000), slipped away from the bloody field of Chickamauga in northern Georgia and into the entrenchments surrounding Chattanooga 10 miles northwest. Not until two days later did the Rebel Army of Tennessee, reduced from a pre-Chickamauga strength of about 66,000 men to 47,500, advance to the gates of the city. It should have been no surprise that the Army of Tennessee tamely and slowly followed up its victory at Chickamauga, for its leader was Braxton Bragg.

Naturally disputatious, and driven by the need to attend to every small detail no matter how irrelevant, Bragg was also tense, arrogant, and a martinet. Never able to get along with subordinates, he lacked the determination to carry through his plans and shrank from decision making. In the words of the late Civil War scholar Bruce Catton, “Braxton Bragg was as baffling mixture of high ability and sheer incompetence as the Confederacy could produce.”

Rosecrans was Determined to Hold Chattanooga

True to form, the 46-year-old North Carolina native and West Point graduate did not exploit the situation created by his victory by rushing the disorganized and dispirited Union defenders out of their fortified camp while they were isolated from any friendly aid. Instead, Bragg spent the week of September 23-29 throwing Confederate pickets around the southern circumference of Chattanooga, thus initiating a blockade of the city and the enemy army that had taken refuge in it. Instead of waging aggressive war upon the foe, Bragg spent most of this period attacking his subordinate commanders with a determined effort to rid his army of them.

In the meantime, Rosecrans’ resolve to hold on to Chattanooga rose and fell with the passage of each day. On the 22nd he wired the administration in Washington, “We are about thirty thousand brave and determined men; but our fate is in the hands of God….” The next day he wrote to President Lincoln directly: “We hold this point, and I cannot be dislodged except by very superior numbers and after a great battle.” And on October 3 Rosecrans suggested to Mr. Lincoln that if his army could remain in Chattanooga, thus forcing the enemy to abandon its present position outside the city, Washington should offer a general amnesty to all Confederate officers and soldiers as a way to end the war!

The president, having previously ordered that Chattanooga remain in Union hands, was shocked by Rosecrans’ idea. Again the leader of the Army of the Cumberland seemed to be hedging on whether he could hold the city, and further poking his nose into political matters by recommending amnesty for the Rebels. It was about this time that Lincoln decided Rosecrans would have to be replaced, but the time was not yet right. His removal would have to wait until Ohio, Rosecrans’ home state, voted in mid-October for a new governor—either the pro-war Republican John Brough or the anti-war Democrat Clement Vallandigham. Congressional seats were also at stake, and Rosecrans’ support of the administration had been long and vocal, going so far as to encourage his soldiers to vote for the continuation of the war effort.

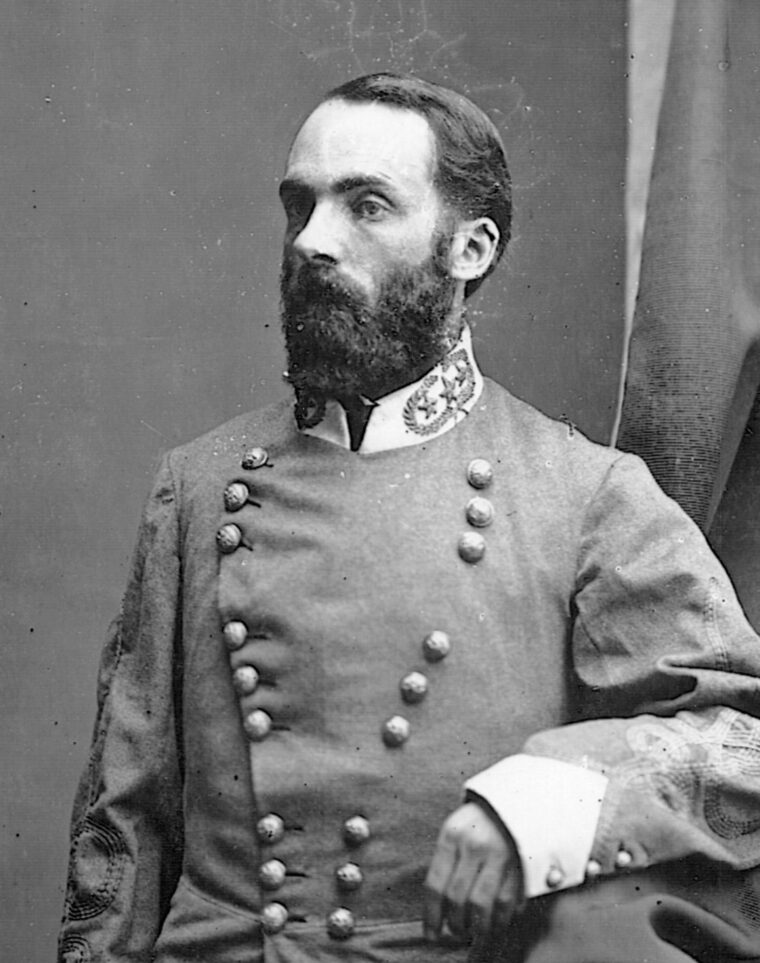

As the political maneuvering in both camps played out, Bragg finally realized that his Northern adversary was not going to oblige him by evacuating his toe-hold in southeast Tennessee just because he was semi-surrounded and under siege. Bragg, seeking some way out of the current impasse, sought advice from his Army corps commanders. Of the number of suggestions put forward, the most promising seemed to originate from Lt. Gen. James Longstreet. Longstreet’s command, an infantry corps of about 14,000 men, had been loaned to Bragg’s army in September in order to resist Rosecrans’ advance on Chattanooga. Consisting of about a third of Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, it had been accustomed to victory and was responsible for delivering the decisive blow at Chickamauga. Having participated in Lee’s daring flank marches against the Federal armies in the East during 1862 and 1863, it was natural for “Old Pete” to recommend such a move to pry the Bluecoats out of their fortified position at Chattanooga.

James A. Longstreet’s Bold Plan

Longstreet’s plan was that the army cross to the north bank of the Tennessee River above the Union-held city and cut Rosecrans’ communications and supply lines leading back to Nashville. Being thus isolated from reinforcements and provisions, Longstreet reasoned the enemy would have to abandon Chattanooga or starve in place. The South Carolinian, reflecting the aggressive strategic vision of his superior, Lee, argued that once the Federals were on the move Bragg could strike once more, destroying them and thus reclaiming middle Tennessee for the South. That done, the Army could then march upon Burnside’s Yankee force at Knoxville and free the “Volunteer State” from the Northern aggressor.

At first receptive to Longstreet’s bold plan, Bragg then rejected it. First, it was too daring for Bragg’s liking; second, his army did not have the transport and supplies needed to head north away from its base of operations; and third, he was suspicious of Longstreet’s motives, fearing that it was all a scheme to replace Bragg with the plan’s designer as the head of the Army of Tennessee. As a result, Bragg took a middle course in order to eliminate Rosecrans and his men. He would keep his foot soldiers near Chattanooga to continue that town’s investment while sending a large cavalry force to sweep into the enemy’s rear area and destroy his remaining supply line. Severed from foodstuffs and reinforcements, the Army of the Cumberland would wither on the vine from lack of subsistence and the means to defend itself. Although a half-measure, the critical situation the Northern army was in held some hope that Bragg’s idea would work. Further, it came to the Southern general’s attention that by late September Union reinforcements from Grant’s army in Mississippi and Meade’s Army of the Potomac were being sent to save Rosecrans. Thus time was running out for the South to retake Chattanooga. Bragg knew he must set in motion an operation that would so panic his weakened foe that it would cause them to abandon the prize they stubbornly held—the strategically vital Chattanooga area.

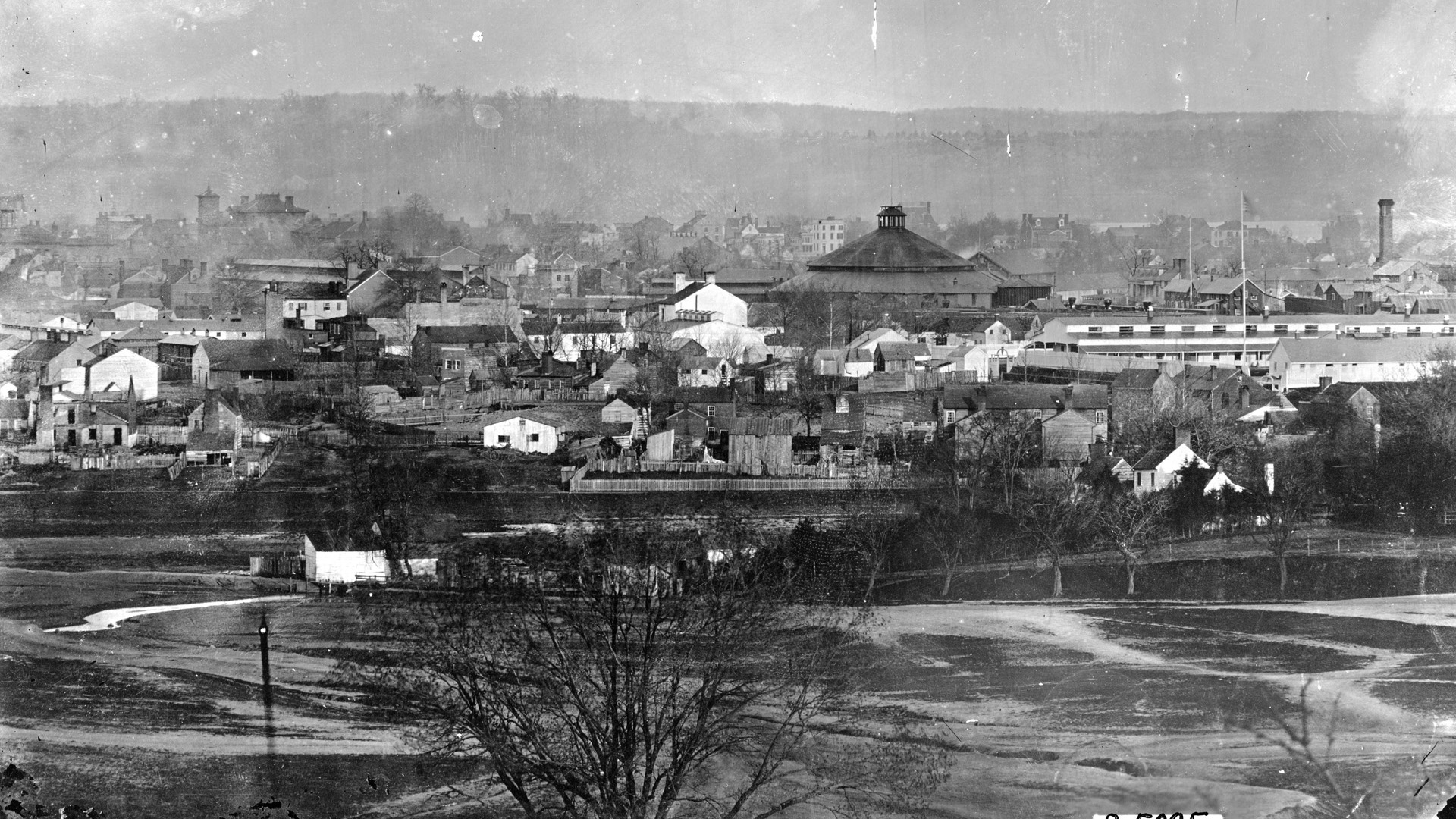

The city of Chattanooga in 1863 was the county seat of Hamilton County, Tenn., with a population, according to the U.S. Census of 1860, of 2,545. Sitting in a large horseshoe bend of the Tennessee River, the town is overlooked to the southwest by the 1,800-foot Lookout Mountain, and on its southeast flank by the 600-foot, 15-mile-long Missionary Ridge.

First settled in 1835, and long referred to as Ross’s Landing, in 1839 it was incorporated as a town, and in 1851 the name was changed to Chattanooga. The name supposedly comes from the Greek phrase for “rock that comes to a point,” which aptly describes the narrowing of Lookout Mountain as it nears the city.

The first 15 years of its existence saw city residents eking out a living transporting goods and people on the Tennessee and smaller area rivers. But by the 1850s the tiny river port began to boom. In less than a decade Chattanooga grew to be a major Southern transportation hub. Four railroad lines converged on the city by 1860—the Chattanooga & Nashville, connecting the Midwest with the lower South by way of Nashville; the Memphis & Charleston, linking West Tennessee with South Carolina; the Western & Atlantic, running to the Atlantic ports; and the East Tennessee & Georgia, uniting Richmond, Va., with the Deep South via Knoxville. Besides the rail lines, local resources of iron, lead, coal, and copper added to the local economic attractiveness.

Protected by the Mountains?

By the third year of the war, Chattanooga’s residents, then about 5,000, thought their isolated mountain location would shield them from the ravages of the coming conflict. On the contrary, the town’s position on the Tennessee River and the rail lines radiating from it made the place the “Gateway to the South.” Occupation by the Union would sever the supply artery that helped feed the Confederate armies in the East via the Lower South. Its railways would allow Federal forces to build up massive power for a drive into Georgia and beyond. Hence the reason for the Union advance on the city by Rosecrans, as well as Lincoln’s demand that it be held, and Bragg’s attempt to retake it after the Battle of Chickamauga.

The Army of the Cumberland lay under siege in Chattanooga from late September to November 1863, but the first month—October—was the worst. From almost the start the Army was confined to a semicircle of land close around Chattanooga itself. The Confederates held the high ground from the north of Missionary Ridge adjacent to the Tennessee River southwest to Rossville. From there Rebel entrenchments dotted the flat lands of Chattanooga Valley, extended westward to Lookout Mountain, and on to Lookout Valley and Raccoon Mountain. A line of rifle pits was also dug at the base of Missionary Ridge. Perched on these eminences, and sheltered by earthworks, Southern musket and artillery fire swept the entire zone between the mountain ranges and the city. To the rear of Rosecrans’ army flowed the Tennessee River—fast, wide, and deep.

The Federal force holed up in Chattanooga had only one viable supply route back to Nashville, its sole source of equipment and food. Union soldiers controlled Bridgeport—the point at which the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad crosses to the south side of the Tennessee River—but Southern possession of Lookout and Raccoon Mountains west of Chattanooga commanded the railroad, the river, and the shortest and best wagon roads both north and south of the Tennessee between the city and Bridgeport. Although the distance between the two places is only 26 miles, the Confederate blocking units from Bragg’s command required that all supplies to the Army of the Cumberland be hauled by a circuitous route north of the river, and over such mountainous terrain that the actual distance involved was 60 miles.

Many of the Draught Animals Died on the Treacherous Trip

The Union lifeline started at Nashville, ran down the tracks of the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad to Stevenson, Ala., and ended its rail trip at Bridgeport. From there all material was convoyed in wagons northeast up the Sequatchie Valley to the town of Jasper, and then on mountain trails (referred to by many who used them as little more than “pig paths”) leading over Warden’s Ridge to the pontoon bridge that spanned the Tennessee River to Chattanooga. The rocky and uneven byways and trails making up this triangular course were so poor that it took a loaded wagon 10 days to make the 60-mile journey, and that was in dry weather. When it rained the paths turned into ribbons of flowing mud, halting all movement by horse-drawn vehicles. Further, the route through the Sequatchie Valley traversed the counties of Marion, Rhea, and Bledsoe, areas that had been stripped bare of forage and feed for the teams of mules and horses pulling needed supplies. As a result, many draught animals did not survive the trip, and the wagons and goods they pulled had to be destroyed or abandoned before reaching the besieged Federals. For the same reason, cattle herds driven through the valley were decimated by starvation before ever getting to Chattanooga. Those that did survive were so thin and malnourished they were called “beef dried on the hoof,” more bone than meat. Finally, the Sequatchie River, running down the full length of Walden’s Ridge and emptying into the Tennessee at Jasper, provided another steep and muddy obstacle to movement in the valley.

Meanwhile, the suffering of the men of the Army of the Cumberland grew. As the weeks went by rations were cut and then cut again. The half rations the men lived on included hard bread and the little beef that got through to the city. Because food was the priority item coming across the Sequatchie Valley, clothes and shoes to replace old and worn-out ones were not to be had. Overcoats and blankets for the coming cold-weather season were unavailable, as were horseshoes, saddles, and horse blankets or anything else that could make a mule or steed serviceable.

Food took precedence even over ammunition. It was calculated by General Ulysses S. Grant that by late October the Army would not possess enough small-arms bullets or artillery shells to fight more than one day’s action. Fuel for the soldiers was in very short supply. After fences and houses in the city had been torn down and used as firewood, the only other available wood to be found was on the north side of the Tennessee. But the lack of enough workable horseflesh prevented this vital resource from being moved across the river once it was cut. The same cause stopped the transport of the wounded and the artillery. The death of 10,000 mules and horses by starvation during the siege partially immobilized Chattanooga’s garrison. With such losses in animals, and the weakened condition of the troops owing to lack of food, it is doubtful if the Army of the Cumberland could have made a successful retreat from Chattanooga, even if the Rebels had allowed it.

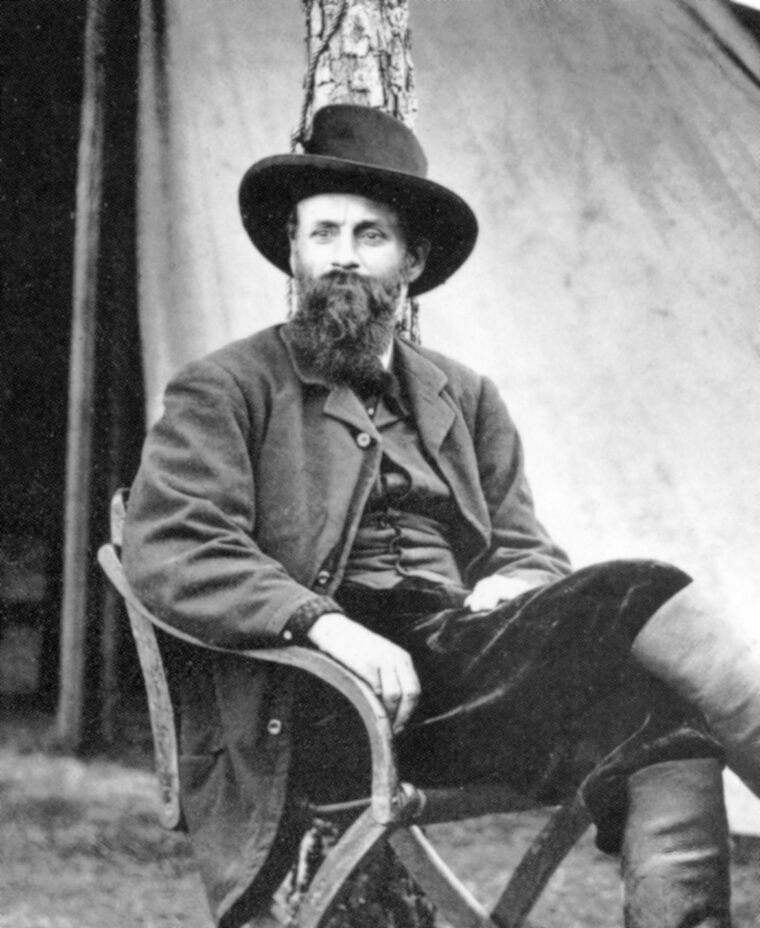

“Fighting Joe” Wheeler

Having a fair idea of the serious straits his opponents were in, and determined to make the situation worse, Bragg issued orders to his cavalry commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler, on September 27 to “cross the Tennessee River and press the enemy, intercept and break-up all his lines of communication and retreat.” In short, Wheeler was to eliminate the Sequatchie Valley corridor and make the isolation of Rosecrans’ army complete.

“Fighting Joe” Wheeler had been Bragg’s cavalry commander since July 1862—first in Bragg’s Army of Mississippi, and then in the newly formed Army of Tennessee, again under Bragg. Born in Augusta, Ga., on September 10, 1836, he was educated in Connecticut and went on to enter the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1854. Graduating with the class of 1859, Wheeler ranked 18th in a class of 22. Assigned to the Regiment of Mounted Rifles (the future U.S. Third Cavalry Regiment) in New Mexico, the young lieutenant resigned his commission in early 1861 and joined the Confederate Army in April of that year. First serving in the artillery and then made colonel of an infantry regiment, Wheeler returned to cavalry duty on Bragg’s insistence. He would be a horse soldier for the rest of the war, proving to be one of the Confederacy’s best commanders of mounted troops.

Before starting his raid around Chattanooga, Wheeler first cleared Lookout Mountain of enemy troops in order to allow Rebel pickets to occupy that strategic height. During this operation Wheeler explained to Bragg that his command was not up to an extended foray into the Sequatchie Valley. Ever since Rosecrans had advanced into middle Tennessee starting with his successful Tullahoma Campaign of late June 1863, right up to the Battle of Chickamauga in late September, Wheeler’s cavalry had been in constant action with the enemy, whether scouting, performing picket duty, or acting as the rear guard for Bragg’s force. Almost four months of hard riding and close contact with Bluecoat riders had taken its toll on the Rebel cavalry by way of broken-down horses, equipment lost or in need of repair and, of course, the utter fatigue of the men.

The condition of his outfit did not augur well for the success of the assignment handed Wheeler, but even worse was to hinder the effort. Along with his weakened divisions, led by Brigadiers John A. Wharton and W.T. Martin, Bragg ordered that General Nathan Bedford Forrest take three brigades from his command to go along with Wheeler. At this point in the war Wheeler and Forrest were bitter enemies. A botched raid on Dover, Tenn., in February 1862, where Wheeler was in charge and Forrest was his subordinate, ended in a costly defeat for the Gray raiders. Forrest, who had been opposed to the plan Wheeler had devised for the operation, swore after the fight that “[I]would be in [my] coffin before I’ll fight again under your command.”

After arguing with Bragg that his men were not up to the task he had given them, Forrest threatened the Army leader with physical violence, and ended his tirade against Bragg by declaring Bragg “was unfit to command an army,” vowing never to serve under him again. Fortunately for all concerned, Forrest very soon after was given an independent command by none other than President Jefferson Davis, thus removing him from the authority of both Bragg and Wheeler for good.

Although Forrest would not be going on the Sequatchie Valley excursion, his now leaderless cavalry under Brig. Gen. H.B. Davison and Colonels John S. Scott and George B. Hodge would be taking part. Like Wheeler’s troopers, Forrest’s three former brigades had performed rigorous service during the Chickamauga Campaign and they and their mounts were in no condition to make the proposed long march. But again ignoring the facts about the state of his cavalry, Bragg ordered Forrest’s former troops to rendezvous with Wheeler’s men on the south side of the Tennessee River at Cottonport, 35 miles northeast of Chattanooga.

Wheeler Spent the Day Weeding Out Soldiers Deemed Unfit for Duty

September 30 saw the juncture of Wheeler’s and Forrest’s commands at Cottonport. Wheeler quickly realized that Forrest had not been exaggerating about the state of his men. As he later reported, “The three brigades from General Forrest were mere skeletons, scarcely averaging 500 effective men each. They were badly armed, and had but a small supply of ammunition, and their horses were in horrible condition, having been marched continuously for three days and nights without removing saddles. The men were worn out, and without rations.” Further, Forrest’s subordinates voiced their opinion that not only were their troopers not up to the mission, but also that the men resented having to again serve under Wheeler. “Fighting Joe” listened to the complaints and rejected them. He spent the rest of the day weeding out those soldiers who were patently unfit for duty, and consolidated Forrest’s men into one brigade under General Davidson.

That evening, led by the 4th Tennessee Cavalry Regiment, Wheeler’s 4,000 troopers and six artillery pieces splashed across the Tennessee River. Dispersed by a charge of the 3rd Alabama Cavalry, supported by artillery, the Yankee picket and two cannon defending a wooded area on the north bank fled the scene. Thus, the Confederates were across the river with only trifling losses and Wheeler spent most of October 1 making further plans. He and the men set off that evening, but gained only 10 miles before a heavy rainstorm made the roads so muddy and the going so difficult that the Graycoats were ordered into bivouac. Meanwhile, the Federals, hearing of the enemy river passage, beefed up their patrols along the Tennessee. Also, three regiments of infantry along with artillery were sent to Anderson’s Cross Roads in the Sequatchie Valley to protect the trains.

Late on October 2, the Confederates were camped on the crest of Walden’s Ridge with a clear view of the Sequatchie Valley below. That night the cavalry commander gathered his officers around him to detail his plan for the morrow. Reporting to the assembled group that a Federal wagon train was only six miles distant down in the valley, Wheeler proposed to take 1,500 men and destroy the enemy convoy. In the meantime, Wharton would pass on to McMinnville about 35 miles northwest. Wharton and Martin protested the division of force in the face of an enemy of unknown strength, but Wheeler held fast, repeated his orders, and finished by saying he would unite with them at McMinnville “tomorrow night, if I am alive.”

At the time Wheeler was outlining his course of action to his men, Brigadier George Crook, in charge of the pursuit of the Rebels, reported to his superior that the Confederates had passed Walden’s Ridge and that he expected to catch up with them the next day.

By 3 am on the 3rd, Wheeler and his detachment headed down onto the valley floor. The rest of his command under Wharton moved toward McMinnville six hours later. After traveling about six miles, Wheeler’s force came upon 32 enemy wagons each pulled by six-mule teams. In the fading dark the Rebels charged their prey, eliminated the train guard, and captured the whole outfit. After securing his first prize, Wheeler moved on at a rapid pace. One hour later his men saw an amazing sight.

The Struggle Included Gun Fire, Swordplay, and Hand-to-Hand Combat

Before them the Confederates beheld an enormous number of white canvas-topped Union wagons stretching for miles along the rutted rocky path that passed for a road. Fanned out along both flanks of the wagon train was a protective screen of cavalry and infantry. Wheeler immediately formed his troopers for battle and sent them forward at the charge.

Colonel John T. Morgan’s 51st Alabama Mounted Infantry struck the wagon guards head on, but was soon thrown back by enemy rifle fire. Seeing this reverse, Wheeler rode up to Colonel A.A. Russell’s 4th Alabama Cavalry Regiment and shouted to Russell to retrieve the day. According to a young trooper of Forrest’s command who took part in this assault, “As soon as our line could be formed, we rode forward at full speed, and receiving a volley at close quarters, were successful in riding and capturing the entire escort within a few minutes.” The struggle had included revolver and rifle fire, swordplay, and hand-to-hand combat along the entire length of the wagon train. After the Unionists threw down their arms in surrender, Wheeler counted the booty: 1,200 officers and enlisted men taken prisoner, along with 800 wagons stocked with provisions, and 4,000 mules.

The next eight hours saw the Confederates burning all the captured wagons and material carried therein that could not be used or spirited off. Along the 10-mile wagon column the Graybacks were ordered to saber or shoot as many of the mules as possible in order to prevent the Federals from hauling away any of the supplies that remained on the field. All through the day the explosion of fired ammunition wagons could be heard in Chattanooga, 20 miles away.

After the orgy of destruction ended, Wheeler’s detachment regrouped and headed for McMinnville. In their wake came their Federal pursuers: Crook and mounted infantry riding into the valley from Walden’s Ridge; General Robert B. Mitchell and Colonel Edward W. McCook rushing up the valley from the direction of Chattanooga.

The Rebels Secured 587 Men, 250 Horses, and Much Needed Stores

After traveling most of the 3rd, the next day, October 4, Wharton’s men prepared to capture the Federal supply depot at McMinnville as they awaited Wheeler’s appearance. By noon, after a Confederate demand for the town’s capitulation, the garrison commander, Major Michael L. Patterson, surrendered. As a result, the Rebels bagged 587 men, 250 horses and mules, a railroad train, and huge amounts of stores. Wheeler’s force reached the town that day, and the united command left McMinnville after sending south their recently acquired spoils. Between October 5 and 6 Wheeler feinted toward the heavily garrisoned town of Murfreesboro, tore up railroad track, and burned every bridge he came to spanning the Stones and Duck Rivers. Wartrace was reached and more supply trains were taken at Christiana and Fosterville townships.

This two-day rampage ended with the Gray riders encamping for the evening (the 6th) near Shelbyville, Tenn., about 20 miles south of Murfreesboro: Davidson’s three brigades three miles west of the town; Martin’s division two miles west of Davidson; and Wharton’s another two miles west of Martin—all north of the Shelbyville-Farmington Road. Wheeler had warned Davidson to be on the lookout for the Federals and to fall back if attacked. For some reason Davidson chose to ignore Wheeler’s directive.

The smoke from the burning Federal dumps at McMinnville was still rising in the sky on October 5 when Crook and his 3,500 men entered that place. After a brief stay they continued their chase and caught up with Wheeler’s rear guard on the Murfreesboro Road about two miles beyond McMinnville. A frontal assault, supported by a surprise rear attack of the 2nd Kentucky (Union) Cavalry Regiment, scattered the Rebel battle line. Nightfall ended the pursuit of the beaten foe. Mitchell and Crook finally combined eight miles from Shelbyville on the 6th.

On October 7 the Federals learned of Davidson’s location and moved toward him, Colonel Miller’s Lightning Brigade of mounted infantry in the van. The first clash occurred between them and Scott’s Confederate unit. The Rebels were routed after they failed to budge Miller and his men with a mounted, and then a dismounted, charge. Davidson, hearing of Scott’s defeat, put his men in motion toward Farmington, leaving Colonel Hodge to hold off the onrushing enemy. Hodge was pressed back steadily toward Farmington and later reported: “For five and a half hours, over seven miles of country the unequal contest continued.” The wooded terrain near that hamlet was unsuitable for mounted action, so the Federals fought on foot. By battle’s end Hodge’s brigade was “cut to pieces and slaughtered” and four cannon were taken by the repeated dismounted charges of the Lightning Brigade. Davidson would have suffered even graver losses if an order by Crook to Colonel Minty’s Brigade to make a flanking attack on the Confederate right early during the fight had been carried out. (Minty denied ever receiving the order and remained in camp during the contest.) The action ceased when the Union troopers were checked by the timely appearance of Martin’s Division, sent by Wheeler to succor Davidson.

On the morning of October 8 the pursuit of the Confederates resumed, but Wheeler had marched all night of the 7th, passing southwest through Pulaski, Tenn., in order to outdistance his opponents. Reaching the ford at Muscle Shoals, Ala., on the Tennessee River at sundown on the 9th, he got the remnants of his force over the boulder-strewn crossing just as the lead elements of the Federals (the 7th Pennsylvania Cavalry) reached the north bank. Wheeler was the last man to cross to the south shore, wet and dispirited. By October 16, the Rebel raiders were back with Brigg’s army.

A Debatable Success?

Was Wheeler’s Sequatchie Valley Raid a success? On the one hand the feat netted the Confederates over 2,000 prisoners, nearly 1,000 enemy wagons, and hundreds of mules destroyed, as well as millions of dollars of enemy property captured or burned. Nine days after the conclusion of the expedition, and partly due to it and his inability to prevent the raid or capture its participants, General Rosecrans was relieved of command of the Army of the Cumberland. Further, on account of the raid, scores of Union troops and animals in the besieged Chattanooga garrison starved from lack of supplies destroyed by Wheeler’s action. (After the destruction of the great wagon train the troops in Chattanooga were forced to go on quarter rations for days.)

Looking at Wheeler’s exploit from another view, it can be argued that it was a failure in both a tactical and strategic sense. First, the Confederates lost between 2,000 and 2,500 men killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, losses that added up to more than those of their opponents. Second, the wastage of the raid in horseflesh and loss of experienced troopers would never be replaced by Wheeler’s command. A larger force of Confederate cavalry would appear in the West for the Atlanta Campaign, but the quality of the new men and horses was below that of what had gone before.

On the strategic side of the ledger, the raid failed in its primary purpose—to ensure that the Army of the Cumberland would leave Chattanooga or starve. With the opening of the “Cracker Line” on October 27, 1863, the supply problems of the city’s garrison were solved. Another failure of the mission was the lack of any real and permanent damage to the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, the main supply artery for any Federal forces operating south of Nashville. Again, on the strategic level, the plight of the Army of the Cumberland, partly due to Wheeler’s raid wrought momentous changes in the conduct of the war in the West by the Lincoln administration, not beneficial to the Confederates. Troops were rushed to East Tennessee, which gave the Federals lasting advantage in numbers; and Grant was placed in charge of all Northern forces in the area, thus ensuring a competent leader and unified command structure, which in time doomed the Confederacy to defeat in the Western theater.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments