By Phil Zimmer

Lieutenant Commander Stephen L. Johnson had a problem on his hands; a very large problem. His Balao-class submarine, the Segundo, had just picked up a large radar contact on the surface about 100 miles off Honshu, one of Japan’s home islands, heading south toward Tokyo. World War II in the Pacific had just ended, and the ensuing cease fire was in its 14th day. The official peace documents would not be signed for several more days, on September 2, 1945, aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.

As Johnson closed on the other vessel, he realized it was a gigantic submarine, so large in fact that it first looked like a surface ship in the darkness. The Americans had nothing that size, so he realized that it had to be a Japanese submarine.

This was the first command for the lanky 29-year-old commander. He and his crew faced the largest and perhaps the most advanced submarine in the world. The Japanese I-401 was longer than a football field and had a surface displacement of 5,233 tons, more than three times the Segundo’s displacement. More troubling though was the sub’s bristling weaponry that included a 5.5-inch gun on her aft deck, three triple-barreled 25mm antiaircraft guns, a single 25mm gun mounted on the bridge, and eight large torpedo tubes in her bow.

The large sub displayed the mandatory black surrender flag, but when the Segundo edged forward, the Japanese vessel moved rapidly into the night. The movement and the continuing display of the Rising Sun flag caused concern. Johnson’s vessel pursued the craft that eventually slowed down as dawn approached. He brought his bow torpedo tubes to bear on the craft as the two vessels settled into a Mexican standoff.

Johnson and his crew had received permission by now to sink the reluctant Japanese vessel if necessary, but he realized he had a career-boosting and perhaps a technologically promising prize in his sights. Much depended on this untried American submarine captain and his wily opponent in the seas off Japan.

Little did Johnson know that the Japanese submarine was a part of the I-400 squadron, basically underwater aircraft carriers, and that the I-401 carried Commander Tatsunosuke Ariizumi, developer of the top-secret subs initially designed to strike the U.S. homeland in a series of surprise attacks. Ariizumi was considered the “father of the I-400 series” and a loyal follower of the emperor with years of experience in the Japanese Navy, so surrender was a disgrace he could not endure.

Johnson also had to contend with Lt. Cmdr. Nobukiyo Nambu, skipper of the I-401, who traced his combat experience back to Pearl Harbor. He now commanded the world’s largest submarine designed to carry three state-of-the-art attack planes in a specially built hanger located atop the vessel. These secret Aichi M6A1 planes were initially designed for “a second Pearl Harbor” or another surprise attack, possibly even against New York City or Washington, D.C. The I-400 series submarines were themselves full of technological surprises. They was capable of traveling around the world one and a half times without refueling, had a top surface speed of 19 knots (or nearly 22 miles per hour), and could remain on patrol for four months, twice as long as the Segundo.

Neither Nambu nor Commander Ariizumi readily accepted the emperor’s surrender statement when it was broadcast on August 15. The subsequent communiqués from Tokyo were exceptionally confusing, especially Order 114, which confirmed that peace had been declared but that all submarines were to “execute predetermined missions and attack the enemy if discovered.”

The I-400: Weapon For a Second Pearl Harbor

It was Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of Japan’s Combined Fleet and developer of the Pearl Harbor attack, who called for the construction of the I-400 series some three weeks after Pearl Harbor. The insightful Yamamoto, who was later killed when his aircraft was shot down by U.S. fighter planes, had toured the United States years before and had warned against a prolonged war with the highly industrialized United States.

However, once Japan was committed to war, he believed that submarine aircraft carriers dropping bombs “like rain” over major U.S. cities would surely cause the American people to “lose their will to fight.” A second surprise attack with even more to come would prove psychologically devastating to the Americans, Yamamoto believed, and perhaps would be the best way to get the Americans to sue for peace.

The Japanese had previous experience with plane-carrying submarines, but these were float planes used largely for reconnaissance. The float planes could be easily shot out of the sky by American fighters, and each submarine carried only one plane, hardly enough to prod the Americans to the negotiating table. Yamamoto always thought big, and he called for a submarine that could travel 40,000 nautical miles without refueling, or nearly four times the range of a Balao-class submarine like the Segundo.

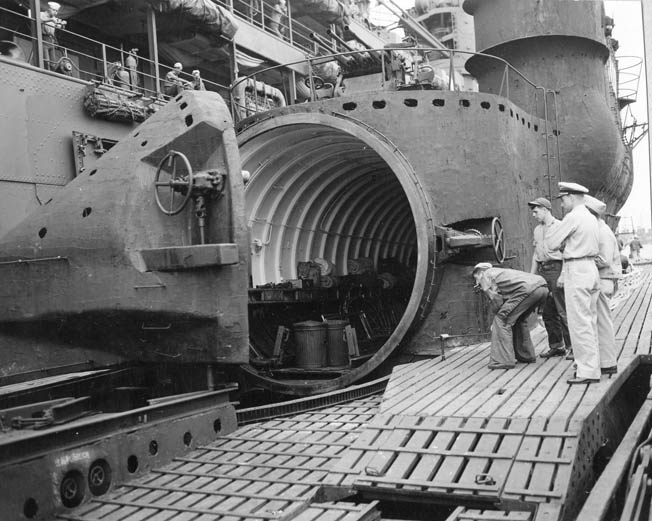

In addition, the I-400 series submarines would carry 1,750 tons of fuel, food for four months at sea for its crew of 147 to 157 men, and two attack planes with a speed of 220 miles per hour and a range of some 600 miles. The hangar atop the sub would need to be at least 100 feet long to initially accommodate two aircraft and be strong enough to withstand the pressure of the deep and a possible attack from enemy planes when surfaced.

Yamamoto’s I-400-class submarines would displace some 6,560 tons submerged, about three times the displacement of the largest U.S. subs, and would be slightly more than 400 feet long, making them about the size of a small cruiser. Because one of the submarines was larger than a destroyer, it “wasn’t an exaggeration, then, to say that Yamamoto was asking for something akin to a small underwater aircraft carrier,” noted one observer.

Yamamoto called for the construction of 18 of the massive submarines carrying a total of 36 attack planes. The plan was rushed through the traditionally slow-moving Japanese naval bureaucracy by June 1942, with construction of the first five subs to begin in January 1943. The name of the special submarine class was abbreviated to Sen-toku.

The attack planes had to be designed from scratch. The need for speed, range and a decent sized bomb payload required tradeoffs. The wings had to be foldable to fit inside the tube, or hangar, atop the submarine. The design work, testing, and building of the plane was outsourced to the Aichi Aircraft Company.

To maximize range and speed, floats were removed from the planes. The crew would circle back after an attack, ditch the plane, and be picked up by the sub. Each plane had a pilot/bombardier in front and a radioman/navigator/tail gunner in the back. Initial plans called for a fixed, front-facing 7.7mm machine gun and a rear-facing 13mm Type 2 gun that was belt fed and handled 300 rounds.

The I-400 program did have its detractors in the heavily bureaucratic Imperial Japanese Navy. After the defeat at Midway in early June 1942, Japan became more focused on defending the homeland and far less on possible attacks on the U.S. mainland using the large submarines. The death of Yamamoto in mid-April 1943, just weeks after his 59th birthday, played further into the hands of conservative Japanese commanders. Cutbacks were ordered in the number of submarines to be built, although the I-400s’ striking ability was to be increased by adding a third attack bomber to the large vessels and adding a second plane to two smaller submarines, the I-13 and I-14.

Equally important, Japanese naval officials realized that with the loss of Guadalcanal, the nation’s defensive perimeter was at dire risk. New York and Washington were dropped as targets for the underwater aircraft carriers in favor of attacking the Panama Canal. A successful attack on the canal would choke the American war machine in the Pacific and buy time for the Japanese to regroup and strengthen the nation’s defensive perimeter.

“Storm From a Clear Sky”

The first test flight of the Aichi attack plane occurred on November 8, 1943. The plane, called Seiran or “storm from a clear sky,” reportedly handled fairly well as the world’s first sub-borne attack bomber. The Japanese began compiling limited available information on the heavily fortified Panama Canal. Their analysis showed that destroying the gate opening onto Gatun Lake would create a massive outpouring of water, destroying the other gates in its path while rushing toward the Caribbean Sea.

The United States had an estimated 40,000 troops defending the canal. The approaches were heavily mined, and there were major fortifications at Colon, Margarita Island, Toro Point, and Fort Sherman. The latter had 16-inch cannon with a range of some 25 miles. Antiaircraft batteries, radar stations, searchlights, nine aircraft bases, and 30 aircraft warning stations rounded out the canal’s defenses.

After weeks of planning, the Japanese came up with a strategy to attack the Gatun locks at dawn when the gates were closed and presumably the defenses were lax. The attack would occur during the dry season because it would take Gatun Lake longer to refill and would be carried out with a combination of bombs and torpedoes. Initially, it was not to be a suicide attack; the pilots would circle back to the submarines and be picked up after ditching their planes.

The planners had nearly a full year to formulate the attack for early 1945. But there were problems ahead because none of the submarines were complete and the planes were not yet in the production stage. Thanks to the virtual blockade thrown around Japan by the U.S. Navy, steel was in particularly short supply in Japan, causing officials to cut back the scheduled production of I-400 subs to five plus the two smaller I-13 and I-14 submarines.

Despite the problems, planning went ahead, revealing how strongly the Japanese believed in the plan to knock out the Panama Canal and thereby stop the increasing flow of American men and war matériel toward Japan. The loss of the Panama Canal might prompt the Allies to modify their demand for unconditional surrender.

Biological Weapons Considered For the Sen-toku Squadron

The Japanese labored on, and by the end of 1944 the I-400 and the smaller I-13 were completed and turned over to the Navy. In early January 1945, the I-401 was commissioned and the I-14, the last of the underwater aircraft carriers, was put into service by mid-March 1945.

The Seiran airplanes were still undergoing testing in late 1944, with the manpower shortage so severe that many of the aircraft workers were 12- to 15-year-old schoolgirls. The Japanese pressed ahead despite problems with the plane’s engines, two earthquakes, and numerous American air raids that slowed production.

As an important aside, it should be noted that while preparations for the attack on the Panama Canal went forward, Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, vice-chief of the Naval General Staff, floated another idea for the use of the Sen-toku submarines. He suggested arming the Seiran planes with biological weapons to be unleashed against a populated area on the West Coast of the United States.

Dr. Shiro Ishii, Japan’s top virus expert and head of the Army’s notorious 731 unit in Manchuria, was consulted. He recommended that the planes drop plague-inflected fleas, something he had tested with success in China, on the United States with San Francisco, Los Angeles, or San Diego suggested as targets. The plan was discarded in late March by the head of the Army’s general staff who called it “unpardonable on humanitarian grounds.”

In effect, the Japanese Army, which had led the development of biological weapons and had tested them on Chinese and American captives, nixed the idea of using the weapons late in the war on American civilians, perhaps in the belief that the war was already lost.

Training For the Raid

The relentless American onslaught had taken a toll. By early 1945, the Japanese Navy had only 20 modern submarines left, including those in the Sen-toku squadron. Problems arose as the two available I-400 subs began test launching their Sieran planes. Each submarine was required to surface and get its three planes unlimbered and aloft within 30 minutes, but actual training showed that it took some 45 minutes. Those additional 15 minutes exposed on the surface could mean the difference between life or death to the pilots and the crews. They also encountered operational problems in getting the aircraft to sputter to life in a timely fashion. Fuel for the submarines and the Sierans was also in short supply. The presence of mines made matters increasingly difficult for the Japanese commanders.

Because of an increasing sense of urgency, the Japanese further modified their plans. A torpedo attack was ruled out because the pilots had not yet acquired the requisite skills. It was decided that each of the 10 planes designated for the Panama Canal mission would carry one 1,760-pound bomb, the largest in the Navy’s arsenal and similar to the one that sank the battleship USS Arizona at Pearl Harbor. In essence, the pilots would now also be on a suicide run because they were to crash their low-flying planes against the locks, thereby ensuring the success of the mission. The pilots quietly accepted the decision.

The departure date was set for mid-June. With continued training, the crews of the larger subs were able to catapult the first two planes off in about four minutes each. With a bit of a struggle, the third plane could be launched in 20 minutes, bringing the total launch time to just under half an hour, which constituted nearly a lifetime when surfaced and bobbing about in heavily patrolled enemy waters.

The Seiran pilots made practice bombing runs in Nanao Bay against a full-sized replica of the Gatun gates. The pilots by now knew what was a stake because the real attack would entail flying in low and fast without floats and with live bombs firmly attached to their planes. Debugging the planes was proving difficult, with nine men killed in crashes and another lost in a nonflying mishap. Training aboard the I-14 proved particularly difficult because it was the last of the four Sen-toku subs to be commissioned and the crew had the least training time.

The Submarines at War’s End

The fall of Iwo Jima in March 1945 and the American attack on Okinawa increased the angst among the Japanese planners as the Americans closed in on the home islands. The war had leaped ahead of the planners, and the slated attack on the Panama Canal was canceled. As noted, there were discussions about possibly using the planes in a surprise attack on San Francisco or Los Angles, but those, too, were put aside in favor of a plan to attack enemy carriers at Ulithi, a large staging area near the island of Truk in the Carolines that was used by the Americans.

The two large subs were to proceed toward Ulithi independently for safety and then rendezvous near the target and launch the attack in mid-August. The I-14 and the I-13 were to reach Japanese-held Truk, get their planes into the air, and report on conditions at Ulithi to ensure that the American carriers were present. The I-13 never made it to Truk and was correctly presumed lost. The I-14 arrived at Truk on August 4, and its planes flew over Ulithi the following day.

Shortly thereafter word reached the submarines that an atomic bomb had destroyed Hiroshima, and on August 15 the Japanese seamen heard the broadcast from the emperor asking his warriors to lay down their arms. Subsequent orders from the homeland were confusing, with one commanding all submarine captains to execute their predetermined missions. On August 16, the underwater aircraft carriers received explicit orders that their planned attack on Ulithi had been canceled just hours before the I-401 was to launch its planes. The subs were ordered to Kure, and the I-401 turned course toward its fateful encounter with Lt. Cmdr. Johnson and the Segundo.

Strategic Successor to the Ballistic Submarine

The Japanese eventually surrendered the I-401 and the other two remaining underwater aircraft carriers. Commander Ariizumi, the developer of the top secret subs, took his own life aboard the I-401 and was quietly buried at sea by the crew. Before encountering the Americans, Nambu had meticusouly followed orders from Japan to raise the black flag of surrender and dispose of the vessel’s weapons, including the planes that were catapulted into the sea. Logbooks, codebooks, and the like were loaded into weighted sacks and tossed overboard. The torpedoes were jettisoned, with one causing alarm as it circled back toward the large submarine before disappearing harmlessly into the depths.

The three submarines drew considerable attention when they made it back to Tokyo Bay. Many Americans initially believed the large hangars atop the subs had been designed to haul supplies to troops on distant islands despite the clearly observed catapults. The Americans did receive some assistance from the Japanese crews as they tried to comprehend the purpose of the extraordinary submarines, and by the end of September the Americans had taken the submarines out for cruises. However, none was taken underwater.

The submarines were then taken to Hawaii for further study. The U.S. Navy gleaned what it could from them, and then all three were deliberately sunk by early June 1946 to keep them away from the prying eyes of the inquisitive Soviets.

One of the Seirans did make it to the United States after the war and was eventually restored at an estimated cost of $1 million. It is now on display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum. Although the U.S. Navy was somewhat dismissive of the massive submarines, it did take a keen interest in the sound-protective coatings used on the vessels.

There is little doubt that the I-400s were the strategic predecessors to today’s ballistic submarines, especially to the Regulus missile program begun about a decade after World War II that carried nuclear warheads inside waterproof deck hangars. In short, Yamamoto’s plan lived on with “new and improved” versions that helped the United States win the Cold War.

Phil Zimmer is a former newspaper reporter and a U.S. Army veteran. He writes on World War II topics from Jamestown, New York.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments