By Eric Hammel

Japan’s road to World War II was a long one. Throughout the late 19th century, the island nation broke out of its feudal past on a path to modernity with a ruthlessness and singlemindedness that would have scared Western nations had they been paying attention.

The modern Japanese Navy was modeled on Britain’s Royal Navy, its army was patterned on the Prussian army, and it imported its new modern industrial base from the best examples the world around. By 1894, Japan was ready to join in the game of empire that had so enriched the major European powers over the previous 400 years.

Japan Expands Into Korea

Japan’s first target for acquisition was Korea. First, in July 1894, it attacked the Chinese forces that outposted the peninsula, then it declared war four days later. The Chinese were routed and a peace treaty was signed in March 1895 that gave Japan access to Korea and Formosa. Shortly, France, Germany, and Russia informed Japan that they would oppose the outright absorption of Korea into a Japanese empire. This so-called Triple Intervention was taken by Japanese leaders to mean that even the most modern Asian state was not to be granted a status equal to that of European nations. This rebuke only fueled Japan’s newfound lust for empire.

Japan needed resources to realize its industrial ambitions. The country possessed precious few of its own, but nearby Korea and adjacent Manchuria had them in abundance. This outlook cast Russia as a leading contender. As proof against the alliance that had denied it a complete domination of Korea, Japan signed a naval treaty with the United Kingdom in 1902. Under the treaty’s terms, the Royal Navy was obligated to support Japan against Russia if Russia acquired just one active ally in a war with Japan. While this treaty raised Japanese prestige in the industrial world, Russia refused to yield in its hostility over the extent of Japanese exploitation of Korea.

Japan went to war with Russia on February 9, 1904. Opening with an attack on the Russian Far Eastern Fleet in Port Arthur, Japan then declared war a day later. The Russian fleet was soundly defeated and a Japanese field army in Korea invaded Manchuria. The Russians dispatched a field army of their own from Europe—which was 6,000 miles away—and a land war ensued. Japan won the land war in a year, and the Russian field army retreated overland.

At sea, the Russian Baltic Sea Fleet completed an 18,000-mile sortie that saw it utterly routed at Tsushima on May 27, 1905. This singular victory, more than anything, raised Japanese prestige among the leading European nations. The United States stood in as an interlocutor. By the terms of a peace treat signed in September 1905 in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, Japan was allowed to fully incorporate Korea into its empire; it also received a lease to exploit Manchuria’s Liaotung peninsula, adjacent to northwestern Korea; and it was given the southern half of Sakhalin Island, to its immediate north.

Distrust of America

An outgrowth of the American role in the peace with Russia was a strengthened mistrust by the Japanese of the United States. The trouble actually started in 1898, with the American acquisition of Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines. To the Japanese, these additions to a fledgling overseas American empire appeared to be direct competition, a limiting factor in the event the new Japanese empire desired to expand eastward at some future date.

Moreover, in 1900, the United States had issued its “Open Door” proclamation, which was aimed in part to forestall direct Japanese aggression in China. There were also racist attacks against Japanese—the “yellow peril”—living in the San Francisco area, where many of the relatively few Japanese immigrants to the United States settled. Indeed, if California-based jingoists had had their way, the United States would have gone to war against Japan by 1908, the year a so-called gentleman’s agreement caused Japan to restrict the emigration of blue-collar workers to the United States.

President Theodore Roosevelt formed the Great White Fleet and sent it off on a world cruise—with a stop in Tokyo—as a sop to anti-Japanese elements in California. The whole purpose of the exercise was to intimidate Japan, but it only deepened her growing animosity toward the United States. By 1913, anti-Japanese sentiment had risen to the point in California and Hawaii that Japanese were singled out among all immigrants to be denied purchase, or even lease, of land in many neighborhoods.

Little Gained at Versailles

A war might have broken out between Japan and the United States by 1914 or 1915, but events in Europe forestalled it by giving Japan an opportunity to match America’s Pacific empire at one swoop. Honoring its mutual defense treaty with the United Kingdom, Japan declared war on Germany on August 23, 1914. Immediately, a Japanese army besieged the German naval base at Tsingtao, China, and forced its surrender in November 1914. A short time later, Japanese troops mounted their nation’s first amphibious assaults against lightly defended German colonies in the Mariana, Marshall, Palau, and Caroline island groups.

In 1915, Japan exploited the weakness of a civilian Chinese regime that had overthrown the imperial system in 1911. It issued a long list of demands for commercial concessions, and the Chinese, who lacked any European backers because of the war, acceded to most of them.

The 1919 peace conference in Versailles granted Japan a mandate over all the former German Pacific possessions north of the equator, and most of the concessions in China remained intact. What Japan was unable to get at Versailles was an explicit expression of racial equality. This it blamed directly on President Woodrow Wilson. Japan’s nationalistic feelings were further hurt when, at the Washington Naval Conference of 1921-1922, it was placed on a footing by which its allotted tonnage in warships was only 60 percent that of the United Stated and the United Kingdom. This rankled beyond the explicit advantage offered the United States; it gave explicit voice to the deeply rooted belief that the United States saw Japan and Japanese as inferior.

As the Russian Revolution moved east across the huge land mass of Siberia, the Japanese Army intervened in its own behalf. To counter Japan’s obvious imperial interests, the United States landed its own troops in Siberia as a somewhat more than tacit statement that it would not countenance a direct seizure of land or wealth north of the pre-war Japanese spheres.

The United States mended a lot of fences in Japan with an outpouring of aid and charity in the wake of the 1923 Tokyo earthquake. But in 1924, trumping all of the previous insensitivity and stupidity in its implicit program to rile Japan on racial grounds, the United States imposed the new Immigration Act to override the merely insulting gentleman’s agreement of 1908 by specifically forbidding any Japanese immigration.

Hirohito vs the Generals

The Showa Emperor, Hirohito, came to power upon the death of his mentally ill and alcoholic father, Taisho, on Christmas Day, 1926. Taisho, perhaps as a reflection of his mental instability, was all for military adventures in East Asia and an eventual showdown with the United States, but Hirohito took an opposite view. He favored a more peaceable approach to Japanese industrial and trade expansion. This placed him at odds with the generals who had exploited and dominated the mad Taisho.

But Hirohito was the emperor, a living god, so they could not act against his person, nor even in a way that appeared to contradict his absolute authority. Fortunately for the generals and their ambitions for conquest, the aesthetic Hirohito, a talented and dedicated marine biologist, was not given to hands-on management of Japan’s affairs. He reigned while others ruled in his place.

By the late 1920s, talk concerning expansion of the Japanese imperial base on the mainland was done under the rubric of “bringing order” to lawless China and its outlying provinces. After the Chinese Revolution of 1911, the nation had balkanized into a network of fiefdoms that became the private plantations of warlords. No powerful central authority ruled China in more than name. Quite aside from the opportunities of empire, there were prominent Japanese who felt that Japan’s destiny was to bring order to lawless, balkanized China.

The Mukden Incident: Political Rise of the Japanese Army

With the emperor’s attention drawn far from the affairs of state, Imperial Army officers began to plan in earnest a campaign that was to eventually bring all of China under Japanese domination—either for purposes of bringing order or outright appropriation of China’s assets, its work force, and its untapped natural resources.

The first step was directed against Manchuria for two reasons: it was only across the narrow Sea of Japan, and its wild rivers could be harnessed to create immense reserves of hydroelectric power that would in turn foster an aggressive industrial reformation. Also, Japanese troops already had a foothold in Manchuria’s southern province, including around the Manchurian capital, Mukden.

The Imperial Army’s Manchuria plan opened on the night of September 18, 1931, with the detonation of an explosive device beneath a railroad track near Mukden. The device had been planted by Japanese under orders from the commander of the Japanese Kwantung Army (based in Korea and southern Manchuria), who acted in defiance of orders from Tokyo to stand down an invasion plan.

Within hours, ostensibly to “bring order,” Japanese troops stormed the city of Mukden, seized the Chinese Army arsenal, and moved out to conquer all of Manchuria. When a League of Nations investigation pinpointed Japanese culpability in the railroad bombing, Japan withdrew from the League, which placed it outside the strictures of international law, such as it was in 1931.

The success of the adventure—which started off with a mutiny against the national authority!—added gloss to the Imperial Army’s résumé and brought forth a rise in the already overt influence the Army had over politics. Moreover, a rather bizarre tradition had sprung up in Japan with respect to the assassination of uncooperative civilian politicians whose policies clashed with the Army’s fine sense of what was and what was not in the interests of the emperor’s greater glory. When Army officers felt they needed to guide events (typically for the greater glory of the emperor), they laid on a culturally acceptable coup d’etat by either tacitly wielding their prerogative of assassination as a tool of intimidation, or by actually cutting off heads.

In the wake of the Mukden incident, a military plot against the cabinet was indeed planned, but it was uncovered. No one died but the government was reliably intimidated and the conspirators received slaps on their wrists. Everyone paid lip service to an admonition that the Kwantung Army stand down, but it did no such thing.

Go-North or Go-South?

The Japanese venture into Manchuria was a mixed blessing. The wild areas could not be tamed by force of arms and it cost as much to defend industrialized areas as the exploitation earned. The military factions that held the most sway in Japanese government had for more than a decade been divided over the issue of where to turn next. One faction embraced the “go north” strategy, meaning both Manchuria and the Soviet Far East; the other advocated a “go south” strategy, meaning resource-rich Southeast Asia, the oil-rich Netherlands East Indies, perhaps even the labor-rich Philippines. Either way meant war––with the Soviet Union or with the Dutch and British, and perhaps the United States.

At first, it was just a debate, but by the end of 1935, the go-north clique felt it had lost the argument. Thus, on February 26, 1936, go-south army officers of middle rank seized a portion of the capital and assassinated several imperial ministers. For once, Hirohito took firm personal control. He ordered his imperial guard to liberate the capital and restore order, which was accomplished fully by February 29. The emperor then ordered the mutineers to be court-martialed, but senior Army commanders ignored the order, though they reported it had been carried out. This false report, when it was revealed via news outlets, caused foreign ambassadors in Tokyo to advise their governments that when Japan went to war, it would move south rather than against the Soviet Union.

Also in 1936, the Japanese announced their withdrawal from the odious and unequal terms of the Washington Naval Conference of 1922. The Imperial Navy had long been gaming the self-policing aspects of the treaty, lying outright about the tonnages and numbers of their warships, but the withdrawal from the treaty made outside inspection impossible even if the other signatories had asked.

“Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”

To counter the alarming influence of the military over the affairs of state, Hirohito in early 1937 named Prince Fumimaro Konoye as his premier. Konoye’s brief was to bring the military in line with the emperor’s views. Konoye tried for a time to impose the emperor’s will, but he lacked will of his own, and the military slipped farther from imperial control than ever it had been. (It must be said that Konoye was one of the aesthetic emperor’s few close friends, someone whom Hirohito apparently could not find fault with, much less rebuke, and even less dismiss.)

Konoye had been premier for only six months when the Army manufactured or exploited an incident at the Marco Polo Bridge, in a demilitarized zone near Peking. A Japanese soldier went missing on the night of July 7, 1937, and the Japanese demanded Chinese help in finding him. The broad implication that the missing man had been kidnapped by Chinese troops led to a number of brawls and shootings that in turn led to pressure on Prince Konoye to sanction the outright invasion of several Chinese provinces. Konoye, who had turned passive in the face of Army demands, acceded to the demands.

All the Japanese objectives were seized well within a six-week time frame offered to Konoye, but throughout the period Hirohito refused to declare war or otherwise personally sanction the conquest. World opinion easily saw through the stated cause of what Japanese diplomats, who had to obey the emperor, painfully referred to as the China Incident.

In November 1937, the utterly compliant Konoye proclaimed the “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere”––a name that seemed to stand in opposition to the domination of so much of China’s trade by European nations and the United States. Suddenly, Japan recast itself as the guarantor of Asian rule in Asia. The Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek, the Chinese supreme warlord whose ideas ran rather more along the lines of Chinese rule in China, immediately declared war on Japan and ordered a nationwide mobilization.

Trade With the U.S. Falls

In Chiang’s declaration of war, Japan’s militarists found a license to run amok in China.

Japanese excesses in the China War are too numerous to describe. To the extent they led to war with the United States, here are the salient facts:

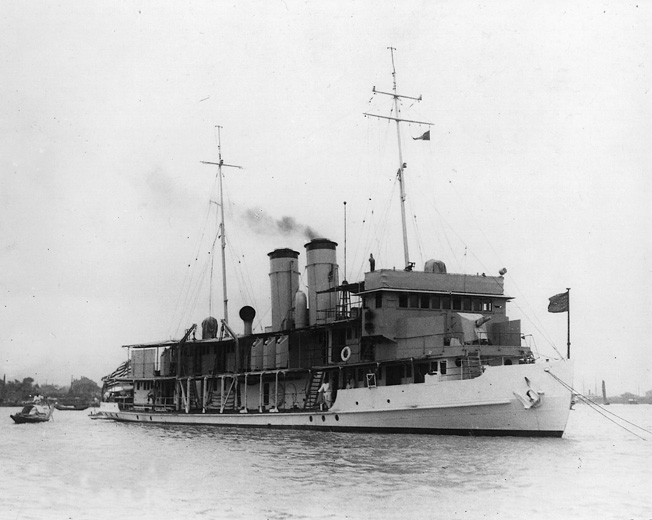

On December 12, 1937, Japanese naval aircraft, guided by an Army colonel out to foment immediate war with the United States, attacked the clearly marked and neutral U.S. Navy gunboat Panay in the Yangtze River near Nanking. Three oil barges under escort by Panay were attacked at the same time. The Panay was hit and sunk, two of the barges were sunk, and three lives were lost. President Franklin Roosevelt was so outraged that he gave a speech in which he suggested that Japan be quarantined, and he followed up with letters in which he asked leading American industrialists to curtail trade with Japan.

Far from working against the Roosevelt administration’s marathon program to reverse the Great Depression, the letter simply pointed out that business might be more profitably and efficiently carried out with European trading partners. The industrialists responded positively to the call, and the Japanese were duly alarmed when Roosevelt’s hand was revealed as the promoter of declining bilateral trade.

The only real consequence of the trade curtailment was Prince Konoye’s eventual resignation, in January 1939. Certainly the Imperial Army didn’t hold back in its treatment of Chinese civilians—of whom hundreds of thousands were murdered.

Japan Becomes an Axis Power

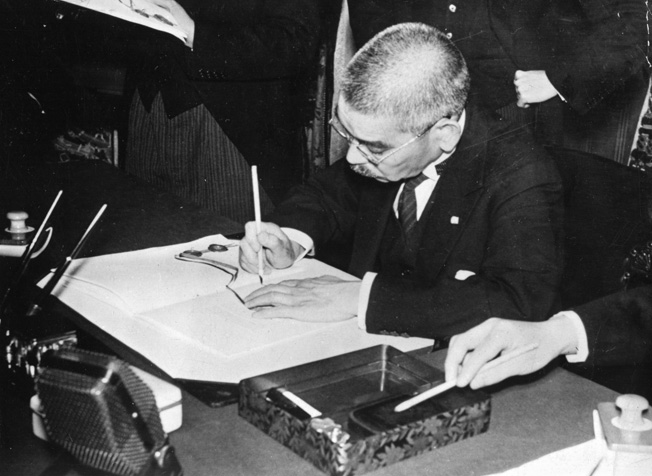

Nothing changed between Konoye’s resignation and his return as premier in July 1940. This time around, the emperor’s friend appointed Yosuke Matsuoka as foreign minister. Matsuoka had lived in poverty in Oregon as a young man but earned a degree at the University of Oregon despite his many hardships. He hated Americans for their racism, whose sting he had certainly felt. Though Matsuoka took office at a time of extreme delicacy in U.S.-Japanese relations, he went out of his way to advocate alliances with Germany and Italy.

The emergence of Japan as an Axis pact signatory in September 1940 did Japan not one whit of good—the Axis partnership was Darwinian, to say the least—and it both alarmed and alienated those many Americans who were otherwise against U.S. rearmament or even alliances with traditional partners such as the United Kingdom. If U.S. policies vis a vis Japan had a racist component (they undoubtedly did, at some level), Japan’s emergence as a full Axis power transcended it. The American press openly characterized Japan as a fascist state, which, at a time of total war in Europe, equated to an enemy of the United States. With or without President Roosevelt’s arguable hostility toward Japan for her own acts and crimes, American public opinion identified Japan as an enemy in some near-future war.

Also in September 1940, Japanese Army units occupied the northern half of Indochina, a French colony. Even though the occupation was undertaken with the approval of the Vichy French government (a German puppet), and despite Japanese pronouncements that the new base of operations would only support the war in adjacent China, Americans felt this was a raw act of cynicism and deceit against a defeated nation that could not defend its own interests.

“Japan Can Now Expand Southward”

President Roosevelt responded to Japan’s alliance with the Axis with ruthless efficiency. The trade treaty between the United States and Japan had already been torn up, but now Roosevelt severely curtailed the licensing of the remaining trade by American companies with Japanese agencies or firms. This draconian policy cast Matsuoka as a dark cloud in the Konoye cabinet, so he set off to Berlin and Moscow in March 1941 in quest of a silver lining.

In Berlin, Matsuoka gained Hitler’s permission to make a treaty with the Soviets. In Moscow, he negotiated a five-year neutrality pact, based on Soviet recognition of Japanese sovereignty over Manchuria and Japanese recognition of Soviet sovereignty over Outer Mongolia. The pact assured Stalin that the Soviet Union wouldn’t be stabbed in the back by Japan, and vice versa.

In the summer of 1938, some diehard Japanese advocates of the go-north strategy had managed to foment a little war with Soviet troops at Kalkhin Gol (also known as Nomanhan), on the ill-defined Manchurian-Outer Mongolian border. In several weeks of burgeoning, all-out ground and air war, the Soviets administered a drubbing that fully ended any notions of Japan’s “going north.”

Stalin had made a similar nonaggression pact with Hitler a week ahead of the dual invasion of Poland in September 1939. Unbeknown to Stalin, as he spoke with Matsuoka, this pact was only four months away from being traumatically overturned by Operation Barbarossa, the German invasion of the Soviet Union. Even more amazing was that, at the end of 1941, Moscow was to be literally saved from German occupation by troops Stalin withdrew from Outer Mongolia on Matsuoka’s word that Japan would not attack again.

And most amazing of all was that Hitler had given Matsuoka permission to make a pact with Stalin that ultimately provided Stalin with the self-same troops who halted the German assault on Moscow.

To top everything else off, as Stalin saw Matsuoka off on the Trans-Siberian train that would take the Japanese foreign minister to Vladivostok, the Soviet supremo bellowed these parting words: “Japan can now expand southward.”

Attempts at Restoring the Trade Relationship

Even as Foreign Minister Yosuki Matsuoka traveled to Berlin and Moscow in the spring of 1941 to nail down Japan’s place in the Axis alliance and a nonaggression pact with the Soviet Union, it appears that Emperor Hirohito expressed his reservations with respect to the downward spiral of Japanese-American relations. He ordered the Japanese embassy in Washington to open talks aimed at restoring normal trade.

It must be said that the Japanese expansion begun in the 1890s was always about commerce and, thus, trade. Japan had no natural resources of her own beyond the compliant hard work of her citizens. Raw materials lay to the west and south, in easy reach for a modern industrial state, but it was all in the hands of white people from far, far away.

Americans are often quick to rationalize the “manifest destiny” that drove expansion of their nation from one ocean to the other. So, too, the Japanese felt it was their destiny to rule an Asia of and for Asians. They thought nothing more of moving west into Manchuria and Korea than the young United States had thought of moving west from Pennsylvania to Ohio and Kentucky—both peoples pushing aside or rolling over backward aboriginals as they went. In both cases, a weak power was to be replaced by a manifestly stronger power, better able to exploit god-given resources to the benefit of all.

So, even though President Roosevelt had staked his public goodwill on halting Japanese expansion, and even though Secretary of State Cordell Hull was as rabidly anti-Japanese as Foreign Minister Matsuoka was anti-American, Ambassador Kichisaburo Nomura arranged to open what was, even in the emperor’s mind, a last-ditch effort to restore trade and, thus, comity between the United States and Japan.

The Nomura-Hull Talks

The talks began in March 1941—around the time Imperial Navy strategic planners began to seriously promote the notion of a preemptive strike against the U.S. Pacific Fleet in place of the defense of homeland waters that had been the hallmark of Japanese naval doctrine, planning, and shipbuilding since the end of World War I.

The U.S. negotiators thought they had an advantage over Nomura and his team. They had broken the secret Japanese codes and could read the “Purple” diplomatic cipher. Underscore that: the diplomatic cipher, not the military cipher. If the Japanese diplomats in Washington were dealt out of the war planning—as they indeed were—there was not necessarily a way for American military leaders to learn of and therefore plan against the emerging preemptive naval strategy.

Short of a shooting war, there is nothing more effective than a trade embargo to demonstrate one nation’s highest degree of disapproval of another nation’s behavior. Trade embargoes cut in two directions; both nations suffer, though not necessarily equally. There was trade between the United States and Japan in the spring of 1941, but it was seriously curtailed on the U.S. side. Japan was suffering, and it was getting the message. It was not processing the message the way the Roosevelt administration hoped it might, but there was still some room to demonstrate yet more disapproval, or to come off the brake and reward what the United States considered to be good behavior.

Besides, the longer the Nomura-Hull talks continued, the more American intelligence agents thought they could learn of Japanese intentions. Yet in that respect it must be said that the intelligence analyst who attempts to gauge future actions by means of what he perceives an enemy’s intentions to be completely misunderstands the workings of intelligence, per se.

Japan as a Continental Power

The only safe bets are those placed on what intelligence agents learn, in aggregate, about an adversary’s capabilities. Absent a fait accompli—a message reading, in effect, “We will attack at dawn”—a good intelligence estimate based on the best and most accurate data can say only, “Beware! The enemy has the capability to attack at dawn.” This is not what American diplomatic and military leaders were getting when their intelligence minions read Nomura’s mail. If they had, they would have foreseen the next really stupid move the Japanese made.

For all that Japan is an island nation, dependent upon shipping for the entirety of its trade, it—like Great Britain—is nonetheless a continental power whose army holds the greater power in military councils. Indeed, in Japan, via its rather aggressive program of selective assassination of officials who did not hew to the Army’s program, the Imperial Army had become the deus ex machina of foreign policy and other important preserves of government.

Japan faces west, across a narrow sea, to the great East Asian land mass. Once it was pulled into the modern world, once it embraced the industrial and imperial models of modern statehood, it became a continental power. True, it ruthlessly drove into the Pacific when the opportunity presented itself in 1914, but its real interests lay in the continent to its west. Japan perceived an enemy to the east, and it prepared itself to take on that enemy in due course, but the Imperial Army was much less interested in seeking redress of an insult over trade than in achieving a position of military and, therefore, economic hegemony over Korea; Manchuria; at least eastern China; and, in due course, oil- and rubber-rich Southeast Asia and the Netherlands East Indies.

The Army’s Drive to Indochina

By mid-1941, the go-north strategy had been completely expunged from Imperial Army planning. Kalkhin Gol had seen to that, and the northern flank had been sealed by Matsuoka’s nonaggression deal with Stalin. That left plenty of room for going south.

The crisis in trade had begun with the Imperial Army’s occupation of northern French Indochina. At the time, the Army and thus the government had claimed that the move had been in the interests of outflanking Chinese land forces in areas north of the Indochina frontier. That was a sop, for whatever it might be worth to whomever chose to listen. The Americans heard it, took it for what it was—then went ahead with ratcheting up their trade embargo.

In July 1941, the Konoye government was dissolved—for one day. When it was reconstituted, the next day, the only change was that Matsuoka, a go-north proponent, had been replaced as foreign minister by a compliant admiral named Teijiro Toyoda.

It must be said that Prince Konoye, by all accounts, personally desired a peaceful outcome to the crisis. But he and the other civilians in his government were so dominated by the military, particularly by the Army, that there was really only one foreseeable outcome.

So, now that the go-south faction was in complete control, and even with the Hull-Nomura talks ongoing, the Army-dominated Konoye regime sent the Imperial Army to occupy the remainder of Indochina. This time, they did not bother to employ the canard about outflanking the Chinese, for it was plain enough to see that southern Indochina outflanks the largest part of Thailand, a militarily weak independent monarchy that oversaw yet more vast, and underdeveloped, natural resources. Thailand then flanked British Malaya to the north and, along with Japanese holdings in China and northern Indochina, most of Burma. At the southern end of Malaya is Singapore, and south of Singapore is Sumatra, in the Netherlands East Indies. Back east of Sumatra is Borneo, where the British colony in North Borneo was the best oil-producing region in Asia.

The Oil Embargo on Japan

The Imperial Army’s plan, which was plain enough before the occupation of southern Indochina, was becoming manifest. The French had not held off the Japanese, and the Royal Thai Army could not do so in its wildest dreams. The British were fighting for their lives in Europe and North Africa, and they had drawn in most of the Australian and New Zealand armies to help them merely hang in against Japan’s European Axis partners. The Netherlands, of course, was under German occupation, so the Royal Netherlands forces in possession of the East Indies were, perforce, both limited and finite. Anyone with a map of Asia and the merest smidgen of deductive powers could see where this was going.

Far from dialing back the sanctions in the face of Ambassador Nomura’s formidable negotiating skills, President Roosevelt ratcheted them up about as far as they could go. Together with the United Kingdom and the free government of the Netherlands, the United States imposed a total oil embargo against Japan on July 26, 1941.

The Nomura-Hull negotiations were allowed to roll on, but the plain fact was that Japan had only 6,450,000 tons of oil in reserve. The most sanguine estimates showed that such a supply could not last beyond four years even with the most draconian regimen of economy. Of course, Japan was involved in a big war in mainland China, so economy was not an option, unless the Imperial Army simply quit the war.

As soon as the oil embargo was announced, the Japanese government released an all-out domestic press assault against the United States. What it came down to was that a jealous, hostile, and much wealthier United States, which had been allowed to find its destiny in its own West, was now leading the charge to deny Japan its destiny to its west.

The Sidelined Imperial Navy

As is the case of all modern continental powers, the Imperial Navy took a backseat to the Army in political matters. Perhaps Japan was an extreme example of a military dictatorship in the 1920s and 1930s, but at root it was dependent upon its army to take and hold the resource-laden lands it needed to at first modernize and then compete on the world economic stage. The Japanese Navy was thus grounded in the traditional role of navies, which is ensuring the unencumbered flow of maritime trade from offshore possessions and, indeed, from trading partners around the world.

The move against German possessions in the Pacific in 1914 had two purposes: to guard the long Pacific trade routes and to mirror and even outflank the string of American bases already extant in the vast ocean. Japan’s acquisition of Formosa in the last years of the 19th century countered from the north the American move into the Philippines, and her acquisition of the Palau Islands further outflanked the Philippines, to the east. The former German possessions in the Mariana Islands countered the American hold on Guam, also in the Marianas; and possession of the far-flung Marshall and Caroline island groups provided a distant barrier far to the east and south. All that Japan lacked by way of a barrier against an American naval advance from Hawaii and the western United States were bases in waters north, northeast, and northwest of the Marianas.

The Imperial Army had absolutely no interest in the far reaches of the Pacific. It occupied Formosa, Korea, Manchuria, and French Indochina; it was massively at work expanding Japanese spheres in China; and it was certainly contemplating moves to and across all of southeast Asia. To undertake the latter, the Army would need the lift capacity available from the Navy, and the invasion fleets would have to be escorted and supported by warships. That was the Navy’s role in the eyes of the dominant Army.

But the Imperial Army had never dispatched, nor did it plan to dispatch, troops and it had never spent, nor did it plan to spend, treasure on the Pacific barrier islands. Inasmuch as the Army controlled Japan’s military purse, little was done in the post-World War I years to exploit the military aspects of the island mandates that had so attracted the Imperial Navy. Plans were made, but circumstances of budget forced the Japanese to go along with the provisos in the Versailles Treaty that prevented fortification of the central Pacific mandates. The Navy didn’t have the funds to fortify any of the Pacific island possessions except the great Truk naval base in the Carolines, and the Army didn’t care to spend any.

The Navy’s Ambitious Pacific Strategy

Aside from building and planning for the defense of home waters against a foe from the east—certainly the United States—the Imperial Navy took on just two tasks once the war in mainland Asia was launched: protecting the narrow sea’s trade routes and sending large parts of its land-based air force to fight in the skies over China. It expected, in due course, to support Imperial Army offensive operations in Southeast Asia in the form of sealift and naval escort, and perhaps air support as well. Its role would be the traditional role of the navy of a continental power.

While waiting and planning for the arrival of an American battle fleet on Japan’s doorstep, a number of influential naval thinkers reconsidered the notion of fighting a grand fleet action so close to home. The Japanese had honed and refined their battle plan—and, perforce, their battle fleet—to the last detail, literally to the last detail. But … what if … ?

What if the Combined Fleet, as the Navy’s operational arm was called, sallied east and took on the Americans close to their home waters? The Japanese knew of the American plan to hold advance bases across the Pacific and seize new ones—the Americans had published its outline. How did that look in reverse? Which American, British, and Dutch bases so threatened Japanese lines of communication that they had to be removed from the board?

Or, even if they didn’t actually threaten Japanese possessions and lines of communication, which American, British, Dutch, and even French possessions would, in Japanese hands, further protect or enhance the Japanese strategic or tactical stance? And, of course, which American possession just south of Formosa, once in Japanese hands, would yield the greatest treasure in resources and colonial workers?

How could the Imperial Navy best hedge its bets in a naval war far from home?

And so the logic became inexorable. And by means of that inexorable logic, the Imperial Navy’s best minds forged an action plan of far-reaching scope and breathtaking ambition.

A few points on personalities that affected the conflicts: Woodrow Wilson was a total failure because of his racism and lack of knowledge in international affairs. He had zero knowledge of Asia and treated Asians with the same disdain he treated Black Americans. He also failed to make clear to Germany (as Teddy Roosevelt would have had he won the election in 1912) that America would fight if its rights on the high seas were interfered with. His fellow democrat president, Franklin Roosevelt, made the same mistake with Japan in 1941. The comments in this article regarding the somewhat pragmatic approach by Hirohito are largely conjecture as he destroyed all his diaries before his death. Finally, the Japanese military leaders, Army and Navy, placed too much credence on their own abilities after their earlier successes against second rate opponents. The Japanese should have learned from the British, also an island nation who they modeled their military after, that Britain’s economic success was due to manufacturing, trade and commerce, not colonies and war which were largely a net drain on the treasury.

What if, as an Axis power, Japan had simply declared war on Great Britain and took Singapore, Borneo, the Dutch possesions etc. off the hands of the continental powers, with Germany’s assent of course. It would have had all it needed to run its war machine without a U.S. declaration of war. Doubtful that the U.S. congress would have wanted a war with Japan over a few scattered colonial possesions on the other side of the world. But they got greedy, wanted the entire western Pacific under their control including Guam and the Philippines, and badly underestimated U.S. resolve and reaction when they attacked Pearl Harbor. A more calculated approached might have worked, at least for a time, or maybe even longer, and Hitler wouldn’t have had a flimsy excuse to declare war on the U.S. either.

Quite correct. Adm. Yamamoto warned of overreach and he was correct.

Japan’s other mistake was not letting its Imperial navy be at the forefront, like Britain whose main defense was its navy, the only country who let their army control was Germany.

It has been recorded that the Japanese Navy had major concerns about U.S. Battleships being bigger and more heavily armed. And, the U.S. Navy had a war-tested veteran from WWI in Admiral Kincaid. The Japanese did not want to slug it out with their battleships and the American battleships because they would have lost. And, then there were the aircraft carriers that the Japs were scared to death of. After sending observers to watch the British carrier-born torpedo bombers take out half of the Italian battle fleet at Taranto harbor, Italy in November 1940. The Japanese learned the use of shallow diving torpedoes from the British since Taranto harbor and Pearl Harbor were shallow. Also, the Japanese lacked signficant technological prowess. After sinking the battleships at Pearl Harbor, the Americans raised and repaired all of them within 12-18 months, except the USS Arizona. The Japanese could not replace their battleships or aircraft carriers and were involved in a zero-sum game.

It should be noted that the Japanese were just as racist as any other country at that time. They believed they were the superior race and part of the reason they took umbrage to what other countries required of them was because of their beliefs. The article seems to be solely from a Japanese point of view. After all, why should they take insult if the US limited migration from their country when they wouldn’t allow anyone to migrate to their country. The real problem the US had was with China.

The troops that went to Russia after WW1 were to help the White Russia army against the Red Army and had nothing to do with Japan. It was only a Brigade and did not stay very long.

Trying to compare what the US did to what Japan did to China and Korea is ridiculous. China and Korea and Japan fought wars with each other for hundreds of years. They had similar technology and they were recognized countries.

Was the US a racist country? Of course it was. All countries during that time were racist by our current standards.

The Japanese government leaders by the authors own admission were liars, murderers, and racist. No better than the Nazis of Germany. They used deceitful tactics to start the war and they murdered POWs.

[email protected]

The Japanese leadership, and the Japanese pubic to the degree they expressed opinions, were definitely racist, as much of the world was at this time. We are better in that regard today, but with a long way to go yet. I can’t defend Wilson but it is a bit odd to complain about ‘democrat’ FDR being racist, considering the record of the GOP over 1920-1932 leading up to the war, including support for Hitler’s fascistic racism right up to Pearl Harbor. The solidly GOP west coast generated much of the anti-Asian fervor in this early period leading up to the war, and they pretty much bulldozed FDR’s administration to implement the internment camps for Japanese during WWII. FDR was a strange bird but no Wilson in terms of racism. It was Eleanor that spurred much of his activities in terms of civil rights, but he was much less racist than his white peers at the time.

Roosevelt opposed the anti-lynching bills that were introduce in congress. He also opposed any form of integration in the armed forces. It is quite right that Eleanor was the driving force behind the Tuskegee Airman and FDR never did much to take credit for it. Probably his attitude toward the Japanese began when he was Assistant Secretary of the Navy and had regarded Japanese naval participation in WW I as self interest in seizing German possessions in the Pacific. An examination of American news reports after Pearl Harbor shows a strong bi-partisan support throughout the country for Japanese internment in the US. While this was most unfortunate, it pales compared to Japanese treatment of Western internees in the areas they controlled.

I was going to reply but you stated everything I would have said only better.