By Sam McGowan

While the surprise Japanese attacks against U.S. military bases in the Hawaiian Islands on December 7, 1941, are certainly the best-known aspect of the opening of hostilities between the two aLess well known today were the Japanese attacks on Clark Field and Iba Field on the opening day of hostilities in the Philippines. While these raids caused tremendous damage, they did not knock Maj. Gen. Lewis H. Brereton’s United States Far East Air Force out of the war, as is commonly believed.

In the early morning hours of December 8, 1941 (still December 7 in Hawaii), Japanese land-based naval bombers and Zero fighters from Formosa were detected by radar heading over Lingayan Gulf in the direction of Manila. American planes were alerted and took off from Clark Field and Iba Field but, after hours of searching, they failed to make contact. The Japanese, on the other hand, had no problem finding their American targets.

The most serious aspect of the raid was the destruction of and damage to the 18 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses that were on the ground at Clark in the midst of refueling and rearming when the attack came. Most of the Curtis P-40 Kittyhawk fighters of the 20th Pursuit Squadron were lost when 10 of the warplanes were caught in the Japanese bomb pattern as they were preparing to take off, while several of the 3rd Pursuit’s fighters ran out of fuel and had to crash-land. The radar facility at the remote airfield at Iba was destroyed.

But half of the 35-plane force of B-17s had been deployed to Del Monte Field at Mindanao, and more than half of the P-40s in the islands had not been involved in the attacks at all. Although its strength had been greatly reduced, the U.S. Army Air Force in the Pacific was still very much in the war.

Recuperating From Losses

After the Japanese bombers and fighters vacated the skies over smoldering Clark Field, the defenders began taking stock of the situation and working to return the airstrip and damaged airplanes to operational service. Luckily, not all of the B-17s at Clark were destroyed; one of the Clark-based Fortresses had been on a reconnaissance mission, and one of the airplanes from Mindanao arrived in the midst of the attack. Both landed safely.

In addition, three of the damaged B-17s were repairable, and mechanics began working feverishly to return them to flyable condition. Two were flown to Mindanao to join the remnants of the 19th Bombardment Group.

On the afternoon of December 8, the 21st Pursuit Squadron was brought up to Clark from Nichols Field, which had yet to be struck. While Clark was under attack, the squadron had been patrolling over the naval facilities at Cavite and never joined the battle. The 17th Pursuit had also been on patrol away from Clark. The planes returned to their base at Del Carmen, a fighter strip some 20 miles south of Clark.

The repair work was carried out largely by individual initiative. From all indications, large numbers of Air Force service personnel abandoned their posts and fled into the cane fields in panic during the attack. But while many of the service troops succumbed to temporary fear, most of the combat crews and the engineers remained on the base and pitched in to repair the damage and return the airfield to service.

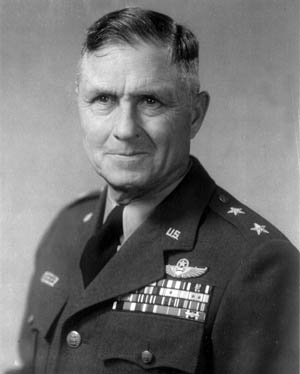

In addition, Lt. Col.—later Brig. Gen.—Eugene L. Eubank, commander of the 19th Bombardment Group, V Bomber Command, stayed with his troops on the flight line, helping to refuel planes and guide in fighters during darkness with a flashlight. As the situation settled down, the men who had fled the stricken base began returning, although their morale remained low. Major Emmett C. Lentz, an Air Force surgeon, rounded up a crew of men and supervised the construction of a dugout infirmary. Master Sergeant George R. Robinet, mess sergeant for the 30th Bombardment Squadron, refused to evacuate his mess equipment and set up facilities by the hangar. (Robinet was famous at Clark, then on Bataan and at Mindanao, for the quality of his mess. He continued to provide the best food possible, even after he was captured and went into a Japanese prison camp.)

Even after the Japanese vacated the skies over Luzon, losses continued among the fighters. A major problem was the dust that covered the airfields, reducing visibility and making flight operations hazardous. The 17th Pursuit lost two aircraft that first night when a pilot tried to take off too soon behind the plane in front of him and collided with another P-40 that was parked nearby. The pilot survived but was seriously burned.

A similar incident the next morning at Clark claimed two P-40s and a B-17. One P-40 pilot taxied into a bomb crater in the dusty darkness and the other, Lieutenant Robert D. Clark, became disoriented and rammed Colonel Eubank’s personal B-17.

Such incidents continued to plague Interceptor Command; at least as many fighters were lost to accident, engine failure, or fuel starvation as to enemy action. By contrast, more than 140 Japanese aircraft would be destroyed by American fighters, bombers, and B-17 gunners. The tragedy was that although the Japanese could send more airplanes down from Japan, whenever an American fighter was lost, it couldn’t be replaced. Within days, few flyable aircraft were left, forcing the young fighter pilots and their ground crews to be assigned to ground-combat duty.

Attack on the Japanese Amphibious Landing

The 34th Pursuit Squadron had seen action on December 8. No orders had been sent to their headquarters at Del Carmen, and they didn’t get off the ground until after the attack. When they did get airborne, they headed for Clark. Although none of their kills were confirmed, the P-35 pilots claimed several Japanese airplanes shot down during a fierce battle near Clark.

The squadron joined the 17th Pursuit in combat patrols over Luzon on December 9, then landed at the satellite field at San Marcelino for the night. There they were joined by some of the B-17s that came up from Mindanao. (Two squadrons of B-17s had been sent to Del Monte Field in early December, and they escaped the carnage that befell their peers at Clark on December 8.) Part of the flight landed at Clark and part at San Marcelino, where they faced miserable conditions. There they found no quarters, food, or potable water. What water there was had to be boiled, and it remained tepid in the tropical heat and humidity of the islands.

The men of the 21st Pursuit were more fortunate. When they landed at Clark, they were directed to a camp that had been set up by the 20th Pursuit in the foothills of the Zambalese Mountains, a few miles from the airfield. There they found some bamboo huts, a few cots, mess facilities, and a flowing stream of fresh water.

Although the Americans did not yet know it, the raids on the aviation facilities were a precursor to an amphibious invasion of the Philippines. The B-17s were brought up from Mindanao in preparation for an attack on the Japanese airfields in southern Formosa. The plan called for a strike by 15 B-17s, with P-40s and P-35s from the 17th and 34th Pursuit Squadrons providing fighter cover before going in to make their own attacks when the bombers departed. A few obsolescent B-18s that had been given to the recently arrived 27th Bombardment Group were also scheduled to join in the attack.

But then reconnaissance patrols detected large Japanese convoys approaching Vigan and Aparri in northern Luzon. V Bomber Command was instructed to cancel the Formosa mission and to direct its efforts against the Japanese invasion. It flew a reconnaissance mission in a P-40 and came back with detailed information on the approaching enemy fleet, but only five B-17s were able to make the attack. Major Cecil Combs, commander of the 93rd Bombardment Squadron, led the flight out of Clark to the target. Each of the five Flying Fortresses carried 20 100-pound bombs, weapons that were too light to do much damage to ships.

The attacking American planes came at 12,000 feet over the beach where the Japanese were preparing to land. They dropped part of their bomb load, then made a second pass from the opposite direction and dropped the rest; they observed some hits and thought one transport was sinking. After unleashing their ordnance, the bombers turned south toward Clark while the escorting P-40s dropped down low to drop fragmentation bombs and strafe the landing barges. Two fighters were lost to engine failure, but the pilots bailed out and eventually made their way to safety.

Combs wanted to rearm and go back for another mission, but the brass at Clark were fearful of another Japanese attack and ordered him to take his airplanes back to Mindanao.

A flight of 16 obsolescent Seversky P-35 fighters took off from Del Carmen, but their worn-out engines began giving problems and 11 of the pilots had to turn back. The other five arrived over Vigan to discover that the earlier P-40 attack had disrupted the landings and that several of the barges had been sunk. P-35 pilot 1st Lt. Samuel H. Marett led his wingman in a daring strafing attack that sank several additional barges and started fires on three transports, including a 10,000-ton troopship.

During Marrett’s final pass, which he made right down on the deck through a wall of gunfire from several ships, his bullets hit the transport’s magazine and set off an explosive cargo. Marett’s P-35 caught the full force of the explosion and shed a wing, then dove into the sea and sank. Marett was killed; his family later received his Distinguished Service Cross, awarded posthumously.

All of the five P-35s that turned back returned to Del Carmen and were parked side by side. Just after the others returned from the mission to Vigan, a flight of 12 Japanese fighters arrived over the field, hitting the fuel trucks and all of the P-35s, destroying a dozen and damaging the other six. Within minutes, the 34th Pursuit Squadron was out of the war.

The Myth and Reality of the Story of Colin Kelly

Early in the morning of December 10, Major Emmett O’Donnell, commanding the 14th Bombardment Squadron, took off from San Marcelino for Clark. O’Donnell and his men in B-17s arrived in a pouring rain, but only three were allowed to land; the authorities at Clark were expecting another attack and didn’t want to risk having six bombers caught on the ground. Three others returned to San Marcelino, then were ordered to Mindanao later in the day.

Not wanting to miss the action, O’Donnell took off alone with eight 600-pound bombs and set a course for Vigan. He attacked a cruiser and destroyer escort but had problems with his bomb-release mechanism. Intent on the target, O’Donnell and his crew made five passes on the two ships and managed to drop all of their bombs, but observed no hits.

While O’Donnell was en route to Vigan, the three bombers that had landed at Clark were being refueled and armed with bombs for an attack on the Japanese invasion area. The loading was interrupted when word came of an approaching Japanese aerial formation and the three B-17s were ordered into the air. Lieutenant George Schaetzel was carrying a full complement of eight 600-pound bombs, but Captain Colin P. Kelly had only three, and the other B-17, piloted by Lieutenant G.R. Montgomery, was carrying only one. Montgomery took his one bomb to Vigan and dropped it with negligible results.

He returned to Clark and was reloaded with 20 100-pound bombs and sent out on another mission to bomb transports sitting just offshore at Aparri, where Japanese troops were also coming ashore; this time Montgomery plastered the target. The crew saw one ship burning when they left the target area. When they reached Clark, they were told to proceed to Mindanao, but they ran into a tropical thunderstorm and became lost. After failing to find Del Monte, Montgomery ditched the B-17 in the water off Zamboanga. Although the airplane was lost, the crew made it to safety.

Colin Kelly and George Schaetzel went out with orders to attack a Japanese aircraft carrier that had been reported north of Aparri. Schaetzel ended up dropping his bombs on the transports sitting off the beach, but clouds beneath them prevented the crew from seeing their bombs’ impact. Schaetzel’s B-17 was quickly intercepted by four Zeros, but despite the bomber’s being shot full of holes, the crew made it back to San Marcelino with no injuries.

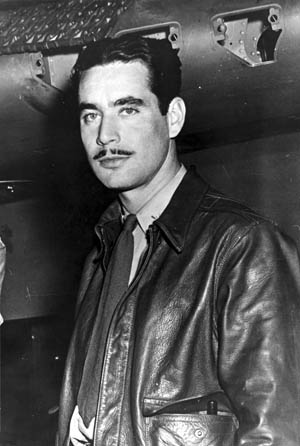

Colin Kelly became a legend of World War II, but the publicized version of his heroic actions was false. After ordering his crew to bail out, Kelly was reported to have sacrificed his life by diving his B-17 into the Japanese battleship Haruna. In fact, there was no Japanese battleship in Lingayen Gulf at the time, and the real story is considerably different from the legend.

Kelly and his crew flew north toward Formosa and came within sight of the Japanese-controlled island. When they encountered a thunderstorm, Kelly turned back and set a course for Aparri, where he knew there were targets. The bombardier, Corporal Meyer Levin, dropped his bombs on what he thought was a battleship, but which was actually a large cruiser, the Natori. The crew saw the flash of a bomb exploding on the stern, followed by a column of smoke emitting from the ship, but could not determine the extent of the damage.

As he circled over the Japanese cruisers, Kelly’s B-17 was jumped by a flight of Zeros. During the ensuing aerial battle, the radio operator, Sergeant William J. Delehanty, was killed and belly turret gunner Pfc. Robert E. Altman was wounded. The intense enemy fire ruptured the fuel tanks in the left wing and the wing caught fire. A third pass cut the elevator cables, forcing Kelly to order his crew to bail out. The bomber exploded in midair before Kelly could parachute to safety—the first American B-17 shot down in combat. The rest of the crew survived, in spite of being strafed by the Japanese fighters while they hung in their parachutes; they were taken prisoner.

The bomber crashed on the plains between Clark Field and Mount Arayat, a dormant volcano just east of the field. Kelly’s body lay nearby, with his unopened parachute still strapped to his body. Captain Colin P. Kelly was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Aerial Brawl Over Luzon

No appreciable damage was done to the Japanese forces at Aparri, but the attacks on the Vigan beachhead had completely disrupted the enemy’s amphibious landings. But the knowledge of what they had done compared to what they could have done if they had had the strength frustrated the young American airmen. The men of the 27th Bombardment Group, whose Douglas Army A-24 Dauntless dive-bombers were still at sea on a different ship than the one that brought them to Manila, were especially frustrated. The dive-bombers were perfectly suited for attacks on ships, as Navy crews would prove later in the war, but these seaborne planes were useless for the time being.

The commanders feared that it was only a matter of time before the Japanese returned in even greater strength and destroyed the U.S. Air Force in the Philippines completely. Therefore, the remaining B-17s were ordered to Del Monte Field on Mindanao and flew no more missions from Clark.

As it turned out, the American pursuit force was nearly wiped out in one fell swoop on the afternoon of December 10. When the Japanese struck Del Carmen, they also hit Nichols Field. At the time the enemy appeared over Luzon, the P-40s of the 17th and 21st Pursuit Squadrons were on patrol, and had been for some time. Approximately 46 P-40s still remained operational, and many of them were in the air at the time of the attack. Some pilots had been airborne for several hours; their airplanes were low on fuel and they were returning to Nichols when they learned that Luzon was under attack.

In spite of their low fuel state—and having no other real choice—the P-40 pilots rushed skyward to engage the enemy. The Japanese bombers were at 20,000 feet—too high for the P-40s to reach in time to intercept them. Suddenly, the fighters were attacked by Zeros, and a major battle ensued that spread over many miles across the sky. The battle was so fast and furious that the P-40 pilots were unable to keep track of the airplanes they shot at––and no one claimed an enemy plane, although it is known that several were shot down.

Even though American pilot losses were light, nearly all of the P-40s were lost. A few limped back to Clark, but three pilots were killed, eight more either bailed out or crashed, and several landed in fields and roads or ditched just offshore in Manila Bay.

Japanese losses were even greater than those of the P-40s, but there were more Zeros to begin with. The high-altitude Japanese bombers were able to make their runs without molestation, their bombs doing tremendous damage to Nichols Field and the U.S. Navy facilities at Cavite. The onshore naval facilities were practically wiped out, a blow that convinced the Navy that it was time to move its surface ships away from Manila.

At the end of the day, the Far East Air Force’s strength was down to 18 B-17s and 30 fighters, with 22 of the fighters being the capable P-40s. The Philippine Air Corps still had a squadron of antiquated P-26s, but their airplanes were no match for the superior Japanese fighters. With air strength rapidly dwindling away, the American command decided that the remaining combat aircraft should be held in reserve for observation work. On the evening of December 10 an order came down that prohibited further combat missions.

Heroes Over the Philippines

Even though the American Air Force was suffering heavy losses, there were some bright spots, and some of them were contributed by the Filipino fighter pilots. Captain Jesus Villamor, squadron commander of the Filipino 6th Squadron, broke up a Japanese bomber formation on December 10, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. One of his pilots, Lieutenant Jose Gozar, attempted to ram a Japanese bomber after his guns jammed. Although the Japanese bomber was too fast for the slower P-26, the attempt caused the enemy pilot to break off his bomb run and flee the area.

Two days later, on December 12, Villamor and six of his men again broke up a Japanese formation before they were attacked by Zeros. Luckily, only two of the P-26s were lost, but the mission was the last interception effort by the Filipinos. They joined their American peers in the reconnaissance role.

After the fighter pilots were officially ordered off combat operations, they continued to take the fight to the Japanese when the opportunity presented itself. They took advantage of their apparent weakness by suddenly striking where and when they were least expected. Lieutenant Grant M. Mahony was on a reconnaissance mission on December 11 when he decided to attack a Japanese-held radio station and the airfield at Legaspi. After he was jumped by nine Zeros, Mahony took his P-40 down to treetop level around an 8,000-foot mountain, then led the enemy planes right back over their own field, where he calmly made another strafing pass!

One of the most exceptional pilots of the Pacific War, Mahony had already realized that the P-40 was faster than the Zero at low altitude. When he was done strafing, he led the Japanese back into the mountains and lost them, then headed home to Nichols Field. Mahony was later killed in action (January 3, 1945) and, like Kelly and Villamor, received the Distinguished Service Cross, posthumously.

In another spectacular effort, Lieutenant Boyd D. “Buzz” Wagner took on two Zeros, then wiped out several others on the ground at Aparri. A trained aeronautical engineer, Wagner knew the P-40 inside and out, and when the two Japanese appeared on his tail, he let them get as close as he felt he could, then throttled back his engine. The startled Japanese flew past the suddenly slowing Kittyhawk, and Wagner promptly shot them both down. He then headed for Aparri at low level to find a dozen Japanese planes on the strip. Wagner strafed the strip and left five Japanese planes burning. It was only when his fuel supply began to dwindle that he returned to his home base.

On December 16, Wagner and Lieutenant Russel M. Church, along with a third pilot, Allison W. Strauss, were dive-bombing an enemy airstrip at Vigan. As they went into a dive against the parked enemy planes, Wagner and Church came under intense ground fire. Church’s plane was hit and set afire but, instead of bailing out, he stayed on his run, released his bombs, then crashed to his death. Wagner continued to pummel the field; he and Church accounted for nearly 20 planes on the ground. Wagner, along with Church’s family, received the Distinguished Service Cross.

Captain Paul Gunn

The day the war began, General Brereton summoned some local civilian pilots to his headquarters and informed them that they were now in the Army. Paul I. Gunn was a former enlisted naval aviator who had retired in the Philippines, where he had been instrumental in organizing Philippine Airlines. His airplanes would be invaluable to the war effort, so Brereton commissioned him as a captain and told him to organize a transport squadron. Immediately upon finding himself back in the military, Gunn showed the stuff that would make him a legend in the Pacific.

He headed to Grace Park, an old airfield on the northern outskirts of Manila that had been incorporated into a Chinese cemetery, and started getting it ready for his new squadron. He knocked down a few tombstones next to the old runway and taxiways and moved his airline to the field. With the airplanes hidden under foliage, for the next several weeks Gunn and his new squadron operated from Grace Park without being discovered by the Japanese.

Gunn threw himself into the fight with a vengeance. Flying as low as he could, he cruised all over the islands in his Twin Beech, transporting a variety of cargo and passengers. He and his six pilots (two Americans, Harold Slingsby and Louis Connelly; the four others were Filipino) carried dispatches, aircraft parts, and passengers to airfields all over the Philippines. Shortly before the holidays, Gunn even flew a load of turkeys to Mindanao for the men of the 19th Bombardment Group and the 5th Air Base Group who were based there. Many of his passengers were military personnel who were being “sent south” to Davao or Zamboanga on the first leg of their journey to Australia.

Gunn and his men were sometimes joined by William R. Bradford, another American pilot who had been in the Philippines for many years and who had run his own air taxi company until he sold it to Philippine Airlines. After the sale, Bradford had joined the staff of Brereton’s Far East Air Force as Technical Inspector of Air Service Command. The American airmen gained important knowledge of the islands—knowledge that would prove invaluable later in the war.

On Christmas Eve 1941, Captain Gunn was ordered to fly a load of Far East Air Force staff officers to Australia and to remain there to organize an air transport unit with whatever resources he could find. He left his wife and four children at their home in Manila and told them he would see them again as soon as he could. That day would not come for more than three years.

Costing Mission Against Legaspi

After the December 10 attacks on Vigan, all of the B-17s of the 19th Bombardment Group were pulled back to Del Monte. Sixteen airplanes were parked on the field but, as of December 12, only six were in commission. All six were scheduled for a raid on Vigan that morning, but one of the airplanes, one of the survivors of the attack on Clark, lost two engines on takeoff—including the one that powered the hydraulic system to operate the brakes. The pilot had to ground-loop the Fortress to avoid plunging into a steep ravine at the end of the runway.

Four of the B-17s bombed the target and returned to Mindanao, while a fifth, which took off late and never caught up with the formation, bombed the target alone, then landed at Clark. When he arrived, the pilot, Captain Cecil Combs, was called to a meeting with Colonel Eubank, who told him he wanted the 19th Bombardment Group to mount a mission against Legaspi with everything they had, and the sooner the better. Combs loaded another B-17 crew into his aircraft for an eventful flight back to Del Monte through heavy thunderstorms. The same storms apparently took the life of Major David Gibbs, who was scheduled to assume command of the 19th Bombardment Group operations at Del Monte, when he crashed later that evening in a B-18.

The immediacy of an attack on Legaspi was necessitated by the presence of a Japanese aircraft carrier. A B-17 crew, commanded by Lieutenant William Bohnaker, spotted the carrier on December 13. Their Flying Fortress broke out of a cloud deck at 2,000 feet and the carrier was right below them, its decks lined with aircraft. But Bohnaker had been ordered not to attack and the Air Force missed its chance to bomb a fat target. When an attack was finally launched on December 14, the carrier was nowhere to be found.

Once again, the 19th Bombardment Group could get only six airplanes—less than one third of the unit’s available strength—into operating condition. One of those blew a tire upon takeoff and two had to turn back, leaving only three B-17s to go on to the target. They flew north over Leyte and approached Luzon from the east. One airplane dropped back when an engine quit, and the pilot had to drop to 10,000 feet before it started again. The other two B-17s also became separated, and were 90 seconds apart when they came over the target––a bay full of ships of all kinds.

Lieutenant Jack Adams’s crew was the first to attack; his bombardier dropped their whole stick of bombs on one pass. Lieutenant Elliott Vandevanter followed; his crew made three passes to drop their bombs before they managed to find sanctuary in the clouds and made their way back to Del Monte.

Lieutenant Hewitt T. Wheless was several minutes behind the other two Flying Fortresses, and his aircraft was attacked by fighters just as he began his bomb run. Nevertheless, he was able to drop eight 600-pound bombs, but the crew was unable to assess the results as they were too busy warding off enemy fighters.

As they came off the target, Adams’s B-17 was jumped by six fighters. The Zeros struck again and again before he managed to reach the safety of a cloud bank. But the damage was done; the stricken B-17 was dropping lower and lower, and Adams had to crash-land in a rice field just on shore on the island of Masbate, southeast of Luzon. One of the fighters strafed the wreck while the crew was climbing out but failed to set the airplane on fire; Filipino civilians rescued the crew. Adams and most of his men eventually made their way back to Mindanao, but the injured radio operator had to be left behind in a hospital on Panay.

Meanwhile, Wheless and his crew were subjected to a 25-minute running gun battle with 18 Japanese planes. The radioman was killed, all four gunners were wounded (one fatally), the No. 1 engine was shot out, and a cannon shell pierced one of the gas tanks. The Japanese fighters drew alongside the damaged B-17, then pulled away and inexplicably left their quarry alone. The B-17 had lost several thousand feet by the time the battle ended and was down to 3,000 feet and still losing altitude. Realizing they couldn’t make Del Monte, Wheless elected to try for a crash-landing at Cagayan, an airstrip a few miles northwest of their base. As night closed in, he found that the airfield had been barricaded, but he had no choice but to land. The landing was made with three flat tires (the result of enemy action) in semidarkness; the only damage sustained upon touching down was four bent propellers, and none of the crew was injured in the landing. His superlative bit of flying earned Wheless the Distinguished Service Cross. (Wheless would later become a three-star general.)

The mission to Legaspi was costly, with two valuable heavy bombers lost. Any results from the bombing were unknown, although gunners on the three B-17s shot down several fighters. It was the last mission flown by the 19th Bombardment Group from Del Monte. The group was down to 14 airplanes and, when Major Birrell Walsh arrived from Clark Field to take command of the group, he requested permission to take the entire group to Darwin for badly needed maintenance and rest for the crews. Some of the bombers would return to Del Monte, but only to use the field as a staging base for missions farther north.

Evacuating the Far East Air Force

The evacuation of the B-17s to Darwin was but the beginning of an exodus of the Far East Air Force from the Philippines to Australia. Although no one in the islands was informed, President Roosevelt, considering the precarious situation with the Navy after Pearl Harbor, had decided that the Philippines were indefensible, and the troops there were to be abandoned to their fate. That decision, though, wouldn’t be made until just before Christmas. Meanwhile, the airmen and troops in the Philippines still held out hope for reinforcement—and would continue to do so right up until the bitter end.

One group in particular was especially frustrated, because they had been in the islands without their airplanes since just before December 8. The 27th Bombardment Group (Light) was supposed to have been equipped with Douglas A-24 Dauntless dive-bombers, but the personnel were sent to Manila on one ship while their airplanes followed on another. The A-24s were still several days from Manila when the Japanese attacked, and the ship carrying them was diverted to Brisbane.

Since their arrival, the men of the 27th had been given a variety of tasks. Some of the pilots had been sent to Clark as replacement pursuit pilots but found themselves assigned to ground duties when they got there; the ground crews were put to work filling sandbags. The only airplanes assigned to the group were a handful of decrepit Douglas B-18s.

On December 17, Lt. Col. John “Big Jim” Davies called some 20 of his best pilots to 27th Group headquarters at Fort McKinley in Manila for a secret meeting. When they were all assembled, Davies told the men that their A-24s had arrived in Australia and they were going to get them. That night, the 20 men left Nichols Field in a Douglas C-39 and two B-18s, one of which had been assigned to the group. One pilot from the 24th Pursuit Group had also been assigned to the flight—Lieutenant Grant Mahony. Mahony was on his way to Australia to organize another fighter squadron. He would fight in Java, then move to India to fight in Burma. He would return to the Philippines in early 1945 and die in the crash of a P-38 while supporting the landings at Lingayen Gulf.

Davies and his men flew to Del Monte, and from there to Darwin. As soon as they arrived, Davies arranged for the three transports that had brought them to return to the Philippines with badly needed .50-caliber ammunition. The 27th contingent finally found passage to Townsville aboard a Qantas Airlines flying boat. When they got there, they discovered that the A-24s were indeed there, but due to a snafu, the airplanes had arrived without needed equipment. It turned out that the group had been given worn-out Navy Dauntlesses instead of new ones, and they were lacking the equipment needed to fight with the Army.

The combination of the foul-up with the airplanes and the changing situation in the Southwest Pacific dictated that the 27th Group pilots would not return to the Philippines. Davies and his pilots would see service in Java, then would join the 3rd Attack Group when it arrived in Australia. The men left in the Philippines would go on to Bataan to fight as infantry, be captured, then make the infamous Death March to the POW camps. The unit designation was transferred to one of the new groups that was organized as America geared up for full-scale war.

Unlike the 27th pilots, some of the 19th Bombardment Group crews continued the fight in the Philippines. The first B-17s arrived at Batchelor Field, a remote outpost in the wilderness some 45 miles from Darwin, on December 17. Five days later, nine 19th Group B-17s were on their way back to the Philippines, this time on a mission to attack Japanese shipping in Davao Gulf, where Japanese landings had commenced two days previously. It was a 1,500-mile mission, and each B-17 had to be modified with additional bomb-bay fuel tanks, leaving room for only four 500-pound bombs. The bombers were to arrive over the target just at dusk, then proceed to Del Monte to refuel and rearm.

They caught the Japanese by surprise and dropped their bombs accurately with very little enemy resistance. Several bombs struck the dock area and one 10,000-ton tanker was reported sunk. Darkness and a gathering evening storm sheltered the Flying Fortresses as they made their way to Mindanao.

When they reached their staging base at Del Monte, orders were waiting, directing them to fly a mission the next evening against Japanese ships in Lingayen Gulf, then to continue on to San Marcelino. Captain Cecil Combs, mission commander of the flight, felt that landing at San Marcelino would needlessly expose the valuable B-17s to the threat of enemy attack, so he decided to play the situation by ear. The six B-17s that were operationally ready took off at 3:00 am the following morning in a driving rainstorm. Their takeoff was planned to put them over Lingayen at dawn.

Shortly after takeoff one airplane lost an engine but, instead of returning to Del Monte, the pilot elected to continue on to Darwin; only four B-17s made it to Lingayen Gulf. After bombing, the crews turned south since it would have been suicidal to land at San Marcelino while being trailed by Japanese fighters. They flew nonstop to a Dutch airfield at Ambon, where they spent the night before continuing on to Batchelor Field near Darwin.

A few days before Christmas, General Brereton received orders to evacuate the head quarters of the Far East Air Forces to Australia, a move precipitated by President Roosevelt’s decision to abandon the Philippines. Brereton himself and several members of his staff left Manila in a U.S. Navy PBY flying boat and Captains P.I. Gunn and Harold Slingsby took out 11 others in two of the Philippine Airlines Twin Beeches, while the Air Force units remaining on Luzon were ordered to move to Bataan and equip to fight as infantry until the “promised relief” arrived from the United States.

Fighting From Bataan

When the Far East Air Forces headquarters pulled out for Australia, Air Force strength on Luzon consisted of only 20 operational fighters—16 P-40s and four P-35s. Colonel Harold George replaced Brereton on MacArthur’s staff and as commander of the Air Force remaining in the islands. There were several brand new P-40s in various stages of assembly, with four almost ready to fly, on the day the withdrawal to Bataan began. In addition to the fighters, a few liaison and observation planes were still operational.

Captain Richard Fellows, commander of the Philippines Air Depot, chose to disregard orders to displace his entire command to Bataan in eight hours. Fellows and his men put forth a herculean effort to move as much of their stock of supplies to Bataan as they could, including the four P-40s, then went out and located badly needed aviation gasoline and .50-caliber ammunition that could keep the remaining aircraft in the air. By early January 1942, all of the air forces on Luzon had relocated to Bataan.

After the move to Bataan, the Air Force crews continued to get in their licks whenever they could. Although the situation was becoming desperate, the fighter pilots strafed Japanese lines of communication. One February mission was an attack on Nichols and Neilson Fields at Manila, which were now in Japanese hands.

The best known of the missions from Bataan was carried out on March 2 when Captain William E. Dyess, Jr., led a flight of four P-40s on a bombing mission against Japanese ships in Subic Bay. Two transports were reported sunk and several smaller ships damaged. Unfortunately, the mission ended with the loss of all four fighters. One was shot down during the other attack and the other three all cracked upon landing back at Bataan.

Contrary to popular belief, the Americans in the Philippines were not cut off from all resupply and reinforcement after the initial Japanese attacks. American transports and converted bombers continued to make flights from Australia to Del Monte right up until the final Japanese effort against the field. Supplies were delivered to Corregidor by submarine—until the Navy decided the submarines were needed elsewhere. Three converted B-24 Liberator transports arrived in Australia in early February and immediately went to work transporting supplies to Del Monte and elsewhere in the southwest Pacific. They were assigned to the 21st Transport Squadron, commanded by Captain P.I. Gunn, who was starting to become famous throughout the region as “Pappy.” Pappy Gunn also made several flights to Del Monte and on to Bataan before Maj. Gen. Edward P. King, commanding general of Philippine-American forces on Bataan, surrendered his men in early April.

Gunn’s family was interned at the Santo Thomas University internment camp, and he was desperate to get them out. On one occasion he landed his Twin Beech on Quezon Boulevard after making arrangements with a Filipino on Bataan who promised to get them out—for $5,000. He waited for 15 minutes, then took off when they didn’t appear.

Other air transport was performed by what the troops came to call the “Bamboo Fleet”—a menagerie of transport and obsolete combat aircraft that included a Grumman Duck, a Bellanca, two Beechcraft, a Waco, and two P-35s. Commanded by Major William R. Bradford after Gunn had been ordered to Australia, the small fleet of transports operated between Bataan and Mindanao carrying badly needed supplies and evacuating personnel. Eventually all of the transports were lost to either enemy action or accident, with Bradford making the last flight in the Bellanca carrying a load of quinine into Corregidor. He crashed on takeoff, thus ending the short history of the Bamboo Fleet.

As the Japanese Army closed in and the situation on Bataan became more desperate, steps were taken to get as many of the Air Force personnel out as possible, particularly pilots and maintenance personnel since they were badly needed to organize new units in Australia. Other Air Force personnel were evacuated by submarine or Navy PBY, but the support troops and some of the aircrew ended up as prisoners of the Japanese. At least three P-40s made it to Del Monte, where they joined three others that had flown up from Australia and continued to fight the Japanese until the airfield was about to be captured.

It was Pappy Gunn who in many ways was responsible for the final American effort in the Philippines and the first offensive Air Force mission of the war. Although he was a highly trained and experienced combat pilot, Gunn was initially assigned to the transport role. But he became close friends with Big Jim Davies, the former commander of the 27th Bombardment Group, and when he spotted a dozen brand-new North American B-25 Mitchells that had been consigned to the Netherlands East Indies Air Force, he rushed to let Davies know they were there.

The two concocted a plan to persuade Eugene Eubank, who was now a brigadier general, to write an order of dubious authority transferring the Mitchells to the 3rd Attack Group, of which Davies was now in command. On March 28, 1942, Gunn was officially transferred to the 3rd Attack Group and within two weeks was on his way back to Del Monte as the pilot of one of 10 B-25s that were part of a mission commanded by Brig. Gen. Ralph Royce to attack Japanese shipping around Cebu. Three B-17s from the recently arrived 7th Bombardment Group plastered enemy-held Nichols Field.

While the Royce mission was operating out of Del Monte, word reached the field that the advancing Japanese were a day away. The crews loaded their bombers with as many men as each could carry and left Del Monte for Darwin. Pappy Gunn was the last to arrive; apparently he had been sent on a secret mission to pick up a Japanese-American intelligence operative who had been pulled out of his position as an infiltrator at the Japanese headquarters in Manila.

The last American airplane out of the Philippines was a B-24 Liberator transport that came in and took off after dark. All of the Philippines were now in Japanese hands.

Abandonment Over Reinforcement

The question has to be asked: What if the U.S. Air Force in the Philippines had been reinforced? Considering the damage done by the small force that hit the Japanese landing party at Vigan, it is possible that, had there been more air power in the islands, the Japanese could have been defeated on the beaches. Even after they got ashore, Air Corps fighters, in particular, often extracted a heavy toll in Japanese blood.

The Allies’ lines of communication from Luzon to Australia did, in fact, remain open for several weeks, although the powerful Japanese naval forces around the island prevented surface reinforcement. Mindanao, however, was free from Japanese attack for several weeks, and American bombers and the small force of transports that were available were able to bring in supplies, even after the Japanese won control of the East Indies.

In spite of the possibilities, the U.S. government decided to abandon the Philippines and forgo any attempt to reinforce the “Battling Bastards of Bataan,” as the Americans in the dwindling Philippine perimeter began calling themselves. Even if Roosevelt had decided to try to reinforce the Philippines as the modified war plans called for, the demoralized military forces in Australia were not up to the task.

And even though there were men such as Pappy Gunn, Grant Mahony, and Buzz Wagner who were willing to go far beyond the call of duty, there were many more who put out much less. In fact, morale among the Air Corps survivors in Australia was so low after the defeat in Java that many of the B-17 crews went on a two-week drunk in Melbourne and refused to even show up for meetings. While their buddies in the Philippines were starting the march into the oblivion of the Japanese POW camps, many American airmen were fighting the Battle of Melbourne.

The time would come, however, when America would reassert her military might and begin the long, slow, and costly reconquest of the Pacific.

MacArthur’s indecision and missed opportunity to bomb the Japanese at Taiwan has cost the deaths of thousands of Americans and Filipinos. What a waste of Philippine money in US dollars paid to this retired, outdated, outsmarted, outmanoeuvered, and arrogant U.S. General of the the Philippine Commonwealth!

I’ll add to that his ill-advised decision to invade the Philippines in 1944-1945 which was arguably tangential to the goal of defeating Japan and certainly cost 10s of thousands of soldiers’ lives (both American and Philippino), many thousands more of Philippino civilians, and the nearly complete destruction of Manila. Nonetheless in my opinion he significantly if not completely made up for those military failings by his masterful oversight of Japanese society and its transformation/recovery during the immediate post-war period. But of course later he botched Korea. A mixed record at best for a very puzzling and enigmatic historical figure.

Really like both comments on MacArthur. I’ve always wondered how his reputation survived the attack on the Filipino Airfields, which followed the Pearl Harbor attack by many hours and found that no new preparations had been made.

Likewise the push years later that he insisted upon, to go through the Filipines wound up totally destroying Manilla.

All the above redeemed by his administration of defeated Japan, it’s a plausible argument. He and the Japanese were a great combination. That said he was responsible for keeping the Emperor in place which was a travesty of Justice. Albeit, arguably a necessary one. Thanks for making the points.

It would be curious to know why FDR and Gen. Marshall insisted that MacArthur should be rescued from the Philippines.

They both knew all the facts and they were well aware of MacArthur’s failures and talents in real-time. They could have easily left MacArthur to be imprisoned by the Japanese.

MacArthur’s slow reaction after Dec.7, ’41 may have been attributed to “information-Overload” for a general who cut his military teeth nearly in the 19th century.

FDR’s and Marshall’s opinions should carry the most weight because neither of them was personally enamored of MacArthur.

We understand from reports that MacArthur had an affinity for the Filipino population. Perhaps that was a factor?

We also know that MacArthur’s arrogance triggered resentment in the press and that members of the press may be even more arrogant than MacArthur. (but with less justification)

Arrogance VS. Arrogance =Irrational hate and jealousy.

The previous comments to which I am replying are well-grounded in historical knowledge and perspective and they gave me “food for thought.”

Thanks for that!

Hi what a good site full of useful info and photos. Very interesting for my reading and research on the war and planes and pilots. On the Feb 9 1942 events i wonder if the Japanese warplanes are id’d correctly as Zeroes? For the P40s battled Japanese Nate fighters. How do i know? For a Warhawk and Nate had a fight and both crashed on Tarac Ridge near Mariveles. Both pilots killed the US pilot LT Stone is still listed as of 2018 as MIA. Not sure if found since. Tho his remains were found by 2 soldiers escaping the ground assault as they climbed up. They found Stone’s body by his wrecked plane and buried his remains. RIP. They got his wallet and a card from it with his info on. Today it’s unsure where his remains are located. We looked at his crash site in 18 and found just plane bits. The Japan Nate wreck is near the top of the ridge and the pilot SGT Kurosawa was found.

Also i read that another P40 crashed into Mt Arayat tho i have no details. Do you? I don’t know the date or pilot or if in battle or what? Does the crash remain and the pilot is he buried or still MIA too? Glad i found your site thanx so much.

My late wife and her family were internal refugees for over three years and spent that time in the jungles of Mindanao. The island had (and still has) the reputation as the wild west of the east. The Japanese garrisoned in large towns but had little control over the countryside. Had MacArthur followed traditional doctrine, a large part of the Army and what was left of the Air Force could have retreated to the island and either held out longer or been evacuated rather than being taken prisoner. As pointed out in this article, re-supply would have been difficult but could have been done at least in the early part of the war. Completely concur in most of the comments about MacArthur. He was/is held in high regard by Filipinos because he did return to end an extremely brutal occupation by the Japanese. The destruction of Manila was carried out by a quite mad Japanese admiral despite the orders of Gen. Yamashita to evacuate. After the war, Yamashita was hanged by MacArthur in what was described as victor’s revenge.