By Chuck Lyons

On a dark night in September 1941, moving at periscope depth, an Italian submarine edged into Gibraltar Bay near the British harbor. Quietly, six men wearing rubber suits with breathing gear scrambled on to the submarine’s deck and mounted three 22-foot long torpedo-like vessels, two men per vessel. The three craft slid from the submarine, floated to the surface, and began silently moving into the bay.

Fifty yards from their targets, they submerged.

“You see your target ship outlined against the sky,” one of the six men later wrote. “You take a compass bearing, flood the diving tank, and the water closes over your head. It is cold and dark and silent.”

Now submerged, the man to the front of each torpedo, the pilot, maneuvered his vessel through the harbor and beneath a British ship where he stopped the motor. While he held the submersible in place, the second man attached two clamps to the keel of the British ship above him and ran a line between them. He then clambered over the pilot to the warhead on the front of the torpedo, attached that to the line, and clambered back.

The pilots detached the warheads, the torpedoes bucking slightly, started their motors, and slipped out from under the British ships.

“Now,” the Italian sailor wrote, “you can think of escape.”

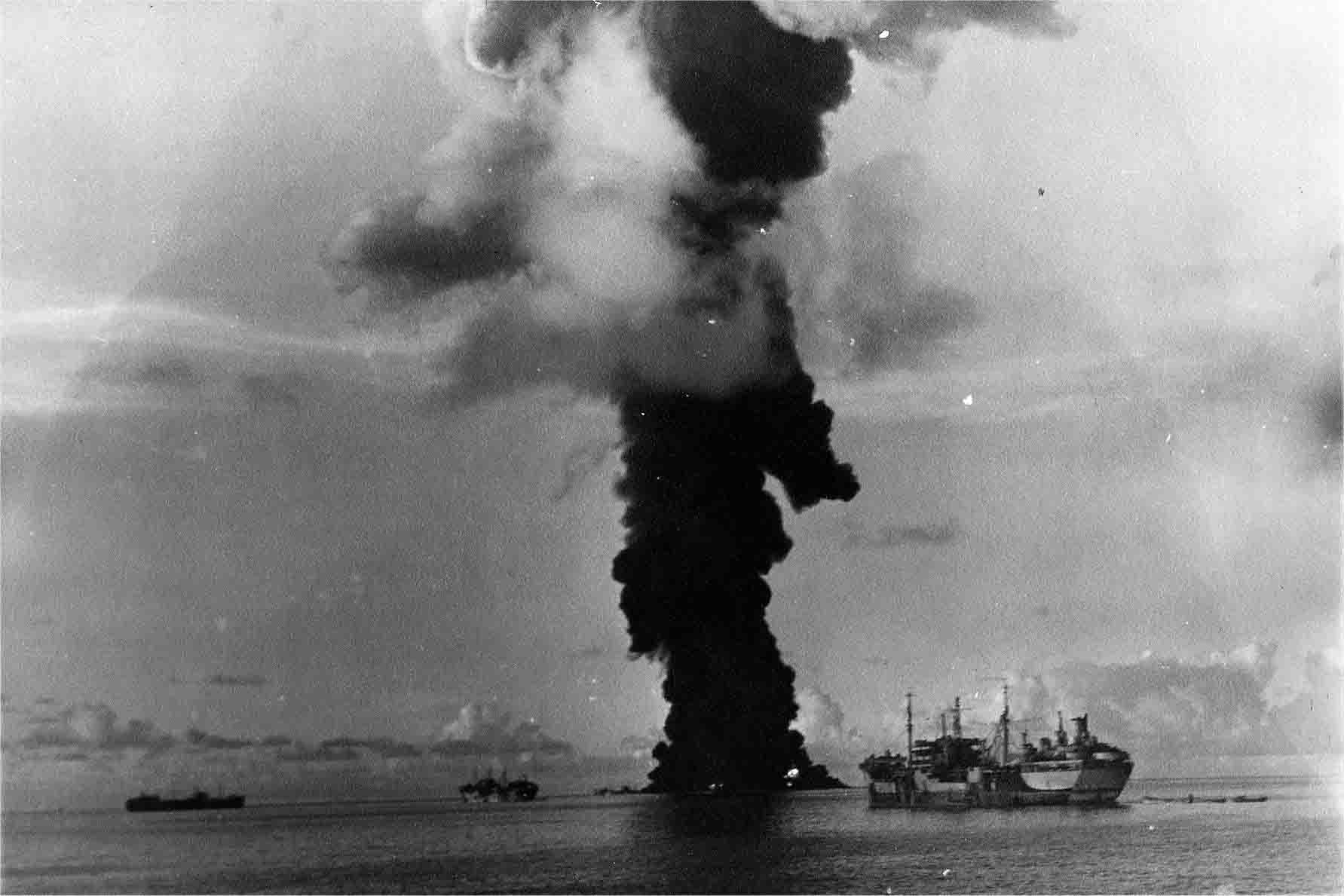

Two and a half hours later, the mines exploded, breaking the backs of the tanker Denbydale, the cargo ship Durham, and the storage tanker Fiona Shell.

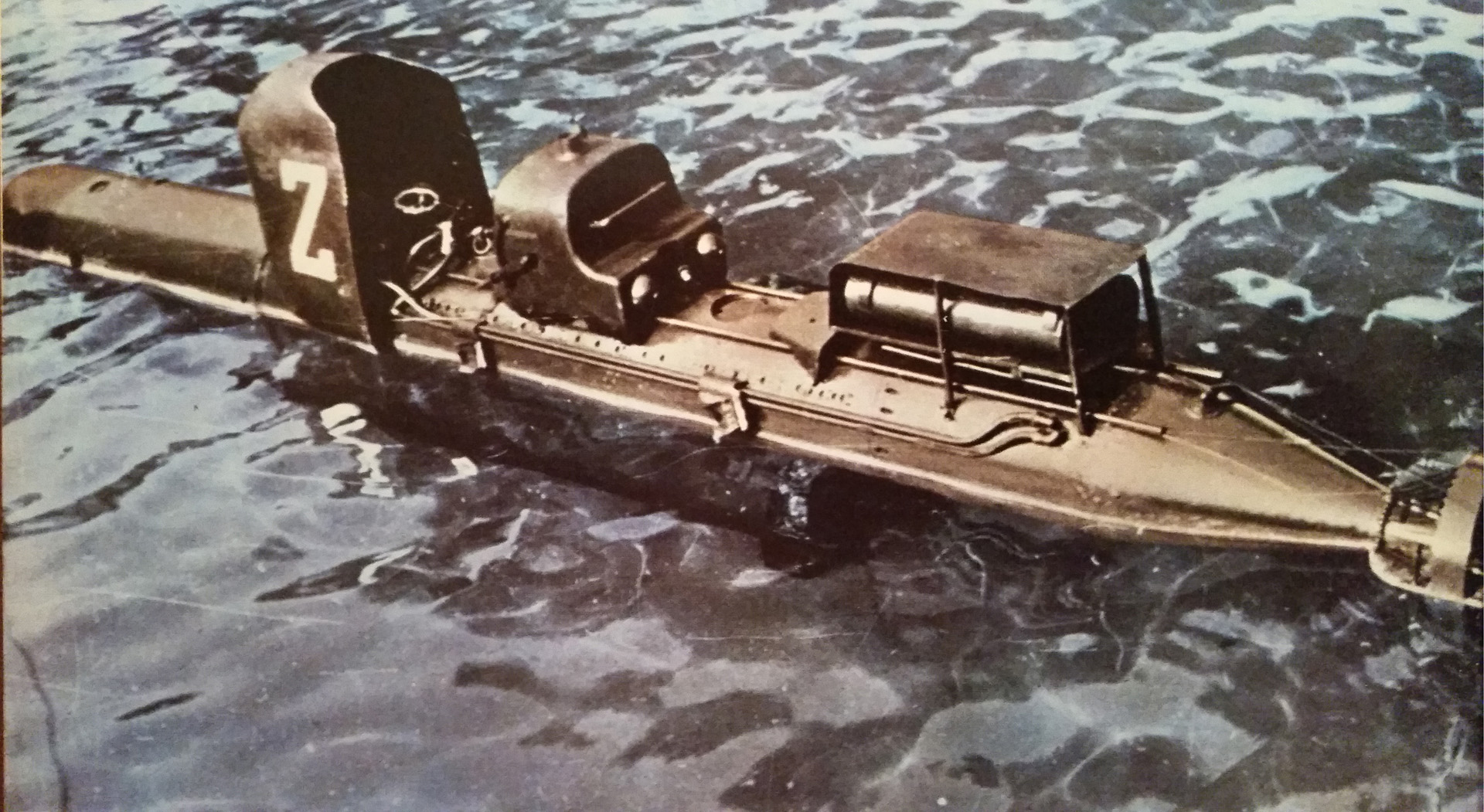

The Gibraltar raid was one of the earliest uses in World War II of a weapon that would become known as a “manned torpedo.” These were small craft, usually submersible, carrying one or two men who rode on the outside of the vehicle, either astride it like a horse or in small compartments. The vessels usually had a detachable warhead and were used for surveillance and surreptitious attacks on enemy shipping.

Invented and deployed by the Italians, who had used a similar weapon to sink two ships in World War I, these manned torpedoes were used in 1941 to attack shipping in Valletta, Malta, and Alexandria, Egypt, as well as at Gibraltar. Other combatants soon followed the Italian lead, developing their own versions of the manned submarine.

These were simple weapons, cheap and easy to mass produce, and during the war they were eventually used by a number of countries besides Italy, including Great Britain, Germany, and Japan among the major powers and such other participants as Yugoslavia and Egypt.

Submersible vehicles may have been used for military purposes as early as the 4th century bc, when, legend has it, Alexander the Great used one for reconnaissance. The Middle Ages gave birth to numerous designs for exploratory and military submersibles, most of which were never built.

The idea of using a small submarine to sneak up on a larger ship and plant explosives to sink it has been around since at least the Revolutionary War. In 1775, Connecticut-born David Bushnell developed the Turtle, a hand-powered submersible using a hand-powered drill and a ship’s auger to attach explosives to a ship. The Turtle was used unsuccessfully to attack British ships in New York in 1776 and was finally sunk.

In 1909, British naval officer and designer Godfrey Herbert developed what was probably the first actual manned submarine, for which he received a patent. But the British War Office rejected use of the vessel in World War I.

It was then left to the Italian Navy to further develop the idea.

In November 1918, Italian naval officer Raffaele Rossetti and another man, wearing diving suits but without any breathing apparatus, rode a primitive manned torpedo Rossetti had helped develop into an Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola on the Adriatic Sea. Using magnetic mines they were able to sink the Austrian battleship Viribus Unitis and a freighter. But since they had no underwater breathing gear, they had to keep their heads above water and were taken prisoner.

In 1938, the Italian First Fleet Assault Vehicles unit was formed as a result of the research and development efforts of Major Teseo Tesei, aided by Major Elios Toschi, who took Rossetti’s 1918 idea and improved it with the addition of a breathing apparatus that allowed the torpedo and the men attached to it to submerge and remain underwater. Tesei’s vehicle, officially named Siluro a lenta corsa (SLC), was later nicknamed the Maiale (pig) because of the steering difficulties it presented.

It was this vessel that was used in the Gibraltar raid, although Tesei had been killed on July 26, 1941, while attacking Malta on an SLC.

At about the same time, a similar idea was coming to the fore in Poland.

In early 1939, as Hitler threatened, a public appeal was made for Poles willing to sacrifice their lives for their country by becoming “living torpedoes.” It is unclear, however, whether such a program had actually been developed or was simply being envisioned. It is also unclear how these volunteers were to be used, if at all. It is possible some sort of manned torpedo was being planned, but how it would be used was never made public.

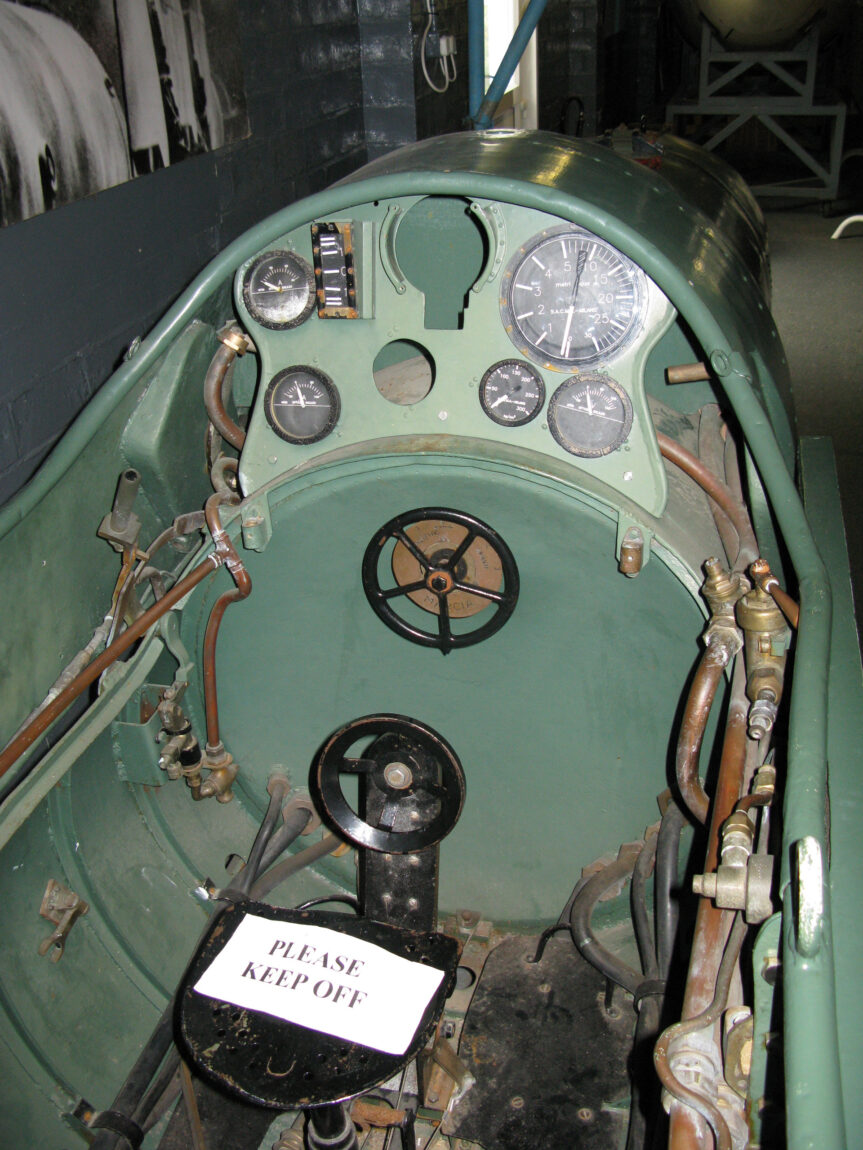

The early Italian vessels were electrically propelled and had a maximum speed of three knots and a range of up to 10 miles. Most of these vessels and others developed during World War II had hydroplanes at the rear, side hydroplanes in front, and a control panel. There were typically four flotation tanks, two to the front and two aft, which were flooded or blown empty to adjust buoyancy and attitude as is done on a submarine. The early vessels were equipped with a compass. In some later versions, riders’ seats were enclosed, and even domed cockpits were added. Most manned torpedo operations were conducted at night and during the new moon to reduce the risk of detection.

Shortly after the September 1941 Gibraltar raid, the Italian Navy began work on a scuttled tanker, the Oterra, in the harbor of Algeciras, Spain, within sight of Gibraltar. Telling the Spanish guards who were in place that they wished to clean the ship’s trimming tanks and to ensure the Oterra’s neutrality, the Italians pumped out the ship’s front, raising the bow, and then cut a hinged door and a watertight compartment there.

After the “cleaning” was complete, the bow was settled back into the water with the door and the watertight compartment below the waves. Telling the Spanish they were moving in boiler tubes to “overhaul the ship’s engines to be ready for victory,” the Italians then loaded several 22-foot manned torpedoes aboard the Oterra.

Beginning in early December 1942, the Italians launched several manned torpedo attacks on Allied shipping from the Oterra, usually in open anchorages. In the first of those attacks, Licio Visintini, who had organized the human torpedo crews, was killed by the British, who were in the habit of firing explosive charges into Gibraltar harbor each night. One of those charges caught Visintini and his partner. Their bodies were found in the harbor two weeks later.

Around the same time, the Italians used manned torpedoes to attack shipping in the eastern Mediterranean, particularly in the harbor of Alexandria, Egypt, where on December 19, 1941, manned torpedoes put the 31,000-ton British battleships Valiant and Queen Elizabeth out of action.

By late 1942, the British had developed their own manned torpedoes, which were called chariots. The two British versions were 20 feet and 30 feet long, capable of speeds of 2.5 and 4.5 knots, and each carried two men. They were capable of deployments of 5 and 51/2 hours, respectively.

In October of that year, two of these new chariots were carried into Norwegian waters aboard a fishing boat to take part in the proposed Operation Title attack on the 42,000-ton German battleship Tirpitz. The two chariots were lost in a storm, however, and the operation was called off.

In January 1943, five chariots were launched near Palermo, Sicily. One was knocked out of action almost immediately when a big wave washed over it, causing it to lose its limpet mines and the gear used to attach the warhead to a ship; another of the manned torpedoes was also damaged. The remaining three chariots were able to continue into Palermo harbor, where they sank the Italian cruiser Ulpio Traiano and badly damaged the converted liner Viminale.

All the chariots were lost in the raid through equipment malfunction, human error, or intentional scuttling. One British submarine was also lost. One charioteer was killed in the attack, and seven others were captured. Two were rescued by the British submarine Unruffled. Two of the captured men later escaped from guards in Rome and hid in the Vatican until the Americans liberated the city in 1944. Two others later escaped from guards in Libya, found a British Army unit, and returned to England.

That same month, two British chariots were deployed to Tripoli in North Africa and used to help prevent blockading ships from being sunk at the harbor mouth.

The most successful British chariot operation, however, came in October 1943, when two Type 2 chariots were launched from a submarine in the Japanese-occupied harbor of Phuket, Siam, and were able to sink two Japanese ships. British chariots were also successfully used to survey the seabed along Normandy’s coast in preparation for the D-Day landings.

By 1944, the German Navy had its own torpedo-like vehicles.

The first German version, the Neger, was a one-man vehicle that carried a torpedo below its hull. It had a range of 48 nautical miles at four knots. The pilot sat in a covered cockpit with air provided and navigated with a wrist compass. He aimed the torpedo by lining up an aiming spike on the vessel’s nose with a graduated scale on the dome.

The Neger was not submersible, and water washing over the dome made visibility extremely poor and aiming difficult, however. The torpedo was released with a lever in the cockpit, and the Neger often and unintentionally became a suicide weapon when the torpedo failed to properly release.

A later German manned torpedo, the Marder, contained a nose tank, allowing it to submerge. Its maximum diving depth was 82 feet. It carried a crew of two men and had two torpedoes below its hull.

These German torpedoes were used mainly along the Normandy beaches at the time of Operation Overlord.

During the night of July 5, 1944, a force of 24 Neger boats attacked the Allied invasion fleet off the coast of Normandy, sinking the British minesweepers Magic and Cato. Fifteen of the Neger vessels were lost in the attack. Then on the night of July 7, another 21 Neger boats launched a second attack, heavily damaging the Polish light cruiser Dragon, which was later scuttled, and sinking another minesweeper, HMS Pylades.

A German midshipman named K.H. Potthast is credited with sinking the Dragon. Potthast later said that he saw several warships in quarter-line formation crossing his path and steered to attack the rear ship, which seemed larger than the others. At a distance of 300 yards, Potthast pulled the torpedo firing lever and turned to escape. His torpedo struck the Dragon with such force, however, that it almost almost hurled his Neger out of the water.

“A sheet of flame shot upward from the stricken ship,” Potthast said. “Almost at once I was enveloped in thick smoke, and I lost all sense of direction. When the smoke cleared I saw that the warship’s stern had been blown away.”

Potthast managed to regain control of his Neger and left the area.

After more than six hours in the cramped cockpit, however, he dozed off. In the morning light, a British corvette attacked. Potthast, suffering from an arm wound, managed to get out of the Neger and was taken aboard the corvette. He was later flown to a British hospital, where he was interrogated but refused to give up any information.

In the end, the interrogators told Potthast that he was solely responsible for sinking the 5,000-ton Dragon.

As one historian wrote, “All this cheered up [Potthast], who felt that his arduous training had not been wasted after all.”

During the fighting in Western Europe and along the French coast, the Royal Navy destroyer Isis was also crippled while at anchor in the mouth of the Seine River. A German manned torpedo was believed responsible.

On August 2, 1944, another 58 Neger human torpedoes and 22 Linsen boats (similar to PT boats) were launched against Allied shipping off Normandy. One Royal Navy destroyer escort, HMS Quorn, was sunk by a manned torpedo. The survivors spent up to eight hours in the water before being rescued. Four officers and 126 ratings died. Forty-one of the Negers and all 22 Linsen boats were lost.

The Imperial Japanese Navy used similar manned submersible craft. The Kaiten (Turn to Heaven) was, unlike the Allied and German submersibles, a suicide vehicle. Although 10 types of Kaiten were developed, only two were produced. Type 1 was 48 feet long and armed with a 3,400-pound warhead. It was capable of a range of 85,300 yards and a speed of 30 knots. The Type 2 Kaiten was slightly longer and capable of 40 knots while carrying the same warhead. It had a hydrogen-peroxide powerplant.

The final designed version was 54 feet long and carried a warhead containing 3,000 pounds of high explosives. It was capable, its developers said, of sinking any warship afloat. That at least was the “prophecy and hope,” as one historian wrote, but the reality was quite different.

Only the Type 1 Kaiten, which was basically a modification of the oxygen-propelled Long Lance torpedo, was ever used in combat. These would separate from their host submarines and speed in the direction fed into their gyroscopes. Once within range, a Kaiten would surface as the pilot checked his range and bearing via periscope and made any necessary adjustments. He would then submerge, arm the warhead, and plow into the side of the targeted ship. In the beginning, the pilot could abandon the vehicle before collision and escape, but few did. In later versions, the pilot was locked into the Kaiten cockpit. In action, the Kaiten was operated by one man, but larger training models could carry two or even four men.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments