By Kevin M. Hymel

“OH MY GOD!” thought tanker Joe Cotten. “We’re shooting machine guns at a Tiger Royal!” It was late December 1944 in the Alsace-Lorraine region of France, near the German border. From inside his M5 Stuart light tank, Cotten had spotted the enemy heavy tank at the bottom of a ridge and had fired at it with his machine gun when he made his realization. The German panzer was stuck on some train lines and had thrown a track. The driver inside was gunning the engine and rocking forward and back, trying to free the behemoth from its trap. Cotten had already fired on a few soldiers escaping the tank, but its crew was obviously still intact.

Cotten knew the tank below possessed an 88mm cannon that fired high-velocity shells, while his Stuart tank had a 37mm cannon and three machine guns—no match for the enemy. An M4 Sherman pulled up beside Cotten and fired a 75mm round at the heavy tank but it ricocheted off. Cotten knew he was in trouble. Then the enemy turret moved in Cotten’s direction and its cannon elevated like an elephant’s snout sniffing the wind. The gunner was looking for him.

Commanding an M5 Stuart with “the Liberators”

Cotten, a platoon leader in Company D, 47th Tank Battalion, 14th Armored Division—the “Liberators”—would have to rely on his training to get out of this tight spot. He had been drafted into the U.S. Army on November 17, 1942. Back then, he was a new father, his baby girl Marty having been born only 17 days earlier. He left his wife, new daughter, and his low-paying job at a railroad shop in Waco, Texas, to train as a tanker.

After induction at Mineral Wells, Texas, Cotten went to Camp Chaffee, Arkansas, and joined Maj. Gen. Vernon Prichard’s 14th Armored Division. Major James W. Lann, who had come up through the ranks of the National Guard and had served as the range officer, commanded the division’s 47th Tank Battalion. Cotten served in the battalion’s Company D under Captain Henry P. Tilden, and he learned how to march and to be a soldier from Staff Sgt. Pennington P. Smith.

“I followed him around,” Cotton said of Smith. “We became good friends.”

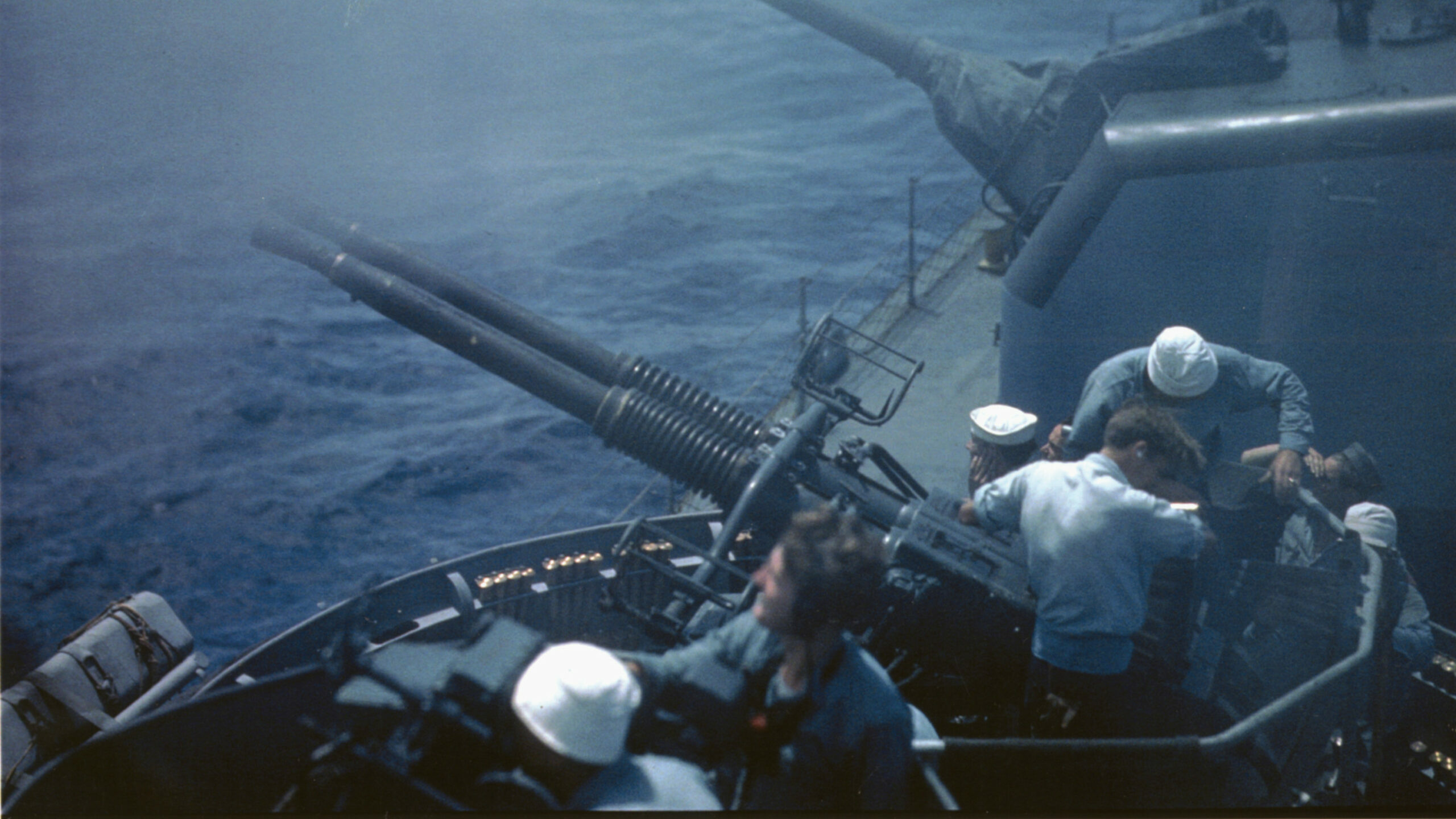

Cotten’s M5 Stuart held a crew of four. In the front sat his driver, also named Smith, and the bow gunner, George Raymond. Deward Key shared the turret with Cotten and served as the 37mm cannon’s gunner. “We called it a pop gun,” Cotten recalled, because it was so inefficient. The M5 was so small that the driver and bow gunner had to close their hatches whenever the turret spun, lest the cannon knock them shut.

From Kentucky to Marseille

Promoted to staff sergeant during training, Cotten was placed in charge of a platoon of five light tanks. In his position, he could talk over the radio with all the tankers in his platoon, as well as his company commander, but he could only listen to the battalion commander.

Once training finished, the whole division transferred to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, to hone its battle skills. It then shipped out for Camp Shanks, New York, where Cotten and his fellow tankers were bussed to the wharf at the Hudson River’s mouth and loaded onto three ships for the trip across the Atlantic Ocean. Their destination: southern France.

After an uneventful ocean journey, Cotten’s ship pulled into the wrecked port of Marseille in southern France on October 28, 1944. His ship had to weave around the partially sunken ships in the harbor.

Once on land, the tankers were driven to a large tank pool outside Marseille to pick out their new vehicles. They then drove them to a range to test-fire the weapons and make any needed repairs. “We had our tanks in good shape,” said Cotten, but he wanted more firepower, so an ordnance crew added a third .30-caliber machine gun to his turret near his hatch. “I used it a lot,” he added.

For extra protection, Cotten and the other tankers stacked sandbags on their tanks to stop Panzerfausts and other antitank weapons.

Fierce Fighting While Cutting Through France

The 14th Armored joined Lt. Gen. Alexander “Sandy” Patch’s American Seventh Army, which had landed in southern France two months earlier on August 14 and had chased the German Nineteenth Army back to the German border where resistance then stiffened. Low on fuel and supplies, Patch’s army halted in the Vosges Mountains to slug it out with the enemy.

Major Lann’s battalion headed east along the Riviera, passing through the ritzy towns of Nice, Cannes, and Monte Carlo—the playgrounds of the rich and famous. The Germans were retreating east and, from time to time, the tankers caught up with rear guards and engaged in fierce firefights.

One day, Cotten and his M5 Stuart tankers were driving in a convoy when they caught up with a freight train filled with German soldiers. The tankers turned their turrets and opened fire. From about 300 yards, Cotten poured fire from his mounted machine gun while other tanks did the same. Some Germans fired back from the train cars’ windows while others jumped out the other side. Cotten could hear the enemy bullets pinging off his tank. “We had a ball firing on them,” he remarked.

In Hog Heaven, Dining Like Aristocrats

During the drive, the tankers sustained themselves mostly on C-rations (canned food) and K-rations (dry food), which were delivered by trucks to the front. Often, the tankers received only hash. “We blamed the drivers for changing out good rations for bad,” Cotten said. He mostly hated the “unmeltable” chocolate bars, known as D-bars. They were hard and rarely softened in coffee. “It was supposed to melt in your mouth … or someplace,” he mused.

Fortunately, one of Cotton’s tankers, Tony Sorgent, loved to cook and created palatable meals for the men on his government-issued portable stove. As the tanks drove across Europe, Sorgent would pick up potatoes, vegetables, and even chickens. Once he had gathered enough ingredients, he broke out the stove and cooked everything in his helmet. In one instance, when he was cooking and the platoon was ordered to move out, Sorgent called to the bow gunner, “Lend me your helmet, mine’s hot!”

While the men rarely went into homes to sleep, they often did enter to dine. In one house, tanker Lowell Carlson found a dining table and adorned it with a tablecloth, fine china, and glassware. Sorgent brought in the food, and the men dined like aristocrats. Once finished, Carlson gathered the four corners of the tablecloth, lifted it into a ball, and tossed it out the window.

To wash down their meals, Cotten and his men sought out alcohol, which was easy to find. “We were in hog heaven!” he recalled. In France, liberated civilians usually handed out bottles of champagne, wine, or cognac. “Champagne was what we were all looking for,” he admitted. The tankers stuffed their bottles in easy access places in their tanks, often under their seats. The men also raided French and German breweries they liberated along the way.

The Battle of the Bulge

The 14th headed north, then turned east into the Alsace-Lorraine region of France on the German border. Farther north, the Germans had broken through the American lines in Belgium and Luxembourg on December 16—and the Battle of the Bulge was on. (Get an in-depth look at the Bulge and other events that shaped the outcome of the war inside WWII History magazine.)

Pushing forward, Cotten’s M5 Stuart headed up a hill and when it crested, he found himself looking down at the German heavy tank rocking back and forth on the train track. He saw several Germans charge out of its hatches and right into the line of fire of his mounted machine gun. That was when he misidentified the tank as a Tiger, and his Sherman tank futilely fired on it.

The tank was not a Tiger but probably a heavy Panzer V Panther, since no Tiger tank units were identified south of the Bulge. The Panther was still a formidable heavy tank, with thick sloping armor and a powerful 75mm high-velocity cannon. During the war, American soldiers often mistook Panthers (and sometimes Mark IV tanks) for Tigers. Cotten simply remembered it as “large, imposing, and unlike any of ours.”

Thinking quickly, Cotten called Captain Tilden, who ordered up two tank destroyers. The tank destroyers roared up, fired two rounds each, and knocked out the enemy tank. Cotten felt a surge of pride later when he drove by the smoldering wreck.

The Blown Bridge Near Haguenau

As the 14th Armored approached the French city of Haguenau, the Germans fought back hard to hold the city’s last remaining bridge over the Moder River. Although firing from well-covered positions, the German infantry was no match for American tanks. “It was a turkey shoot!” recalled Cotten.

Major Lann did not think so, calling over the radio, “Let’s get our act together.” Then, suddenly, the bridge exploded, shaking Cotten’s tank. “We could see the damn thing blow,” he recalled. The Germans stuck on the west side of the river began standing up and surrendering. Many simply raised their arms and put their hands behind their necks. It took three trucks to haul away all the Germans.

Once the fighting died down, Cotten came across Staff Sgt. Pennington P. Smith, the soldier he admired so much, lying wounded behind a tank. A bullet had entered his head below one of his ears and exited the other side; he drifted in and out of consciousness. Thinking Smith was going to die, Cotten gave him his crucifix, put him on his tank, and drove him to an aid station.

Contending with the Dragon’s Teeth

In late December, the division closed in on the German border, with Lann’s battalion supporting the 103rd Infantry Division. The tankers came across concrete pylons blocking their advance—the Dragon’s Teeth, part of Adolf Hitler’s homeland defense. The tanks stopped while engineers figured out the best way to defeat the obstacles.

As they waited, a tanker approached Cotten, concerned about attacking through the Dragon’s Teeth. Cotten knew the man, because he was constantly saying, “Let me at ‘em!” and boasting of his military prowess. This time, the man looked pale and worried. He told Cotten, “I can’t do it. I can’t do it,” then fell to the ground and started shaking uncontrollably.

Cotten called for a medic, who exclaimed, “Oh my God! He’s cracked up totally!” The medic gave him several shots of morphine, but as some men took him he away, he still shook, groaned, hollered, and roared. “He was not someone you wanted to be around or depend on,” Cotten explained. The man never returned to the unit.

Heading for Hatten after Christmas

As it turned out, the M5 Stuart tankers did not go through the Dragon’s Teeth at all. The engineers blew them up and cleared two paths through the remaining pylons. When they detonated the explosives attached to the obstacles, Cotten and his men were close enough to feel the impact. “Stuff blew all over,” he said, “concrete was flying around.” One piece smacked him in the head but did no damage.

Christmas Day passed uneventfully, but for New Year’s the men parked their tanks near a Catholic church and attended a midnight Mass with a German woman. “She was a nice lady,” remembered Cotten. After the short break from war, everyone manned their tanks and headed east for the French city of Hatten, on the German border, which had been evacuated in 1939 for the building of the Maginot Line. After Germany’s 1940 invasion of France, the 1,500 inhabitants returned.

“It Was the First Time We Looked Them in the Eye”

As the division closed on Hatten on January 9, 1945, the Germans ambushed two jeep-bound scouts with the 94th Reconnaissance Squadron. Stanley Spalding was driving the jeep ahead of Cotten’s tanks, clearing the way for the armor, when the Germans opened fire on him and his companion. Spalding kicked the other man out of the jeep, saving his life, but the German fire killed Spalding. Cotten did not know Spalding at the time, but he would know of him later.

With the Battle of the Bulge turning in the Allies’ favor, the Germans had launched Operation North Wind (Nordwind) on December 31, 1944, attacking into Alsace-Lorraine and other northeastern regions of France, with the goal of wrecking Patch’s Seventh Army and retaking the French city of Strasbourg.

The city of Hatten stood between the Germans and the 14th Armored Division. “That was the first time we looked them in the eye,” recalled Cotten. Despite 14 inches of snow on the ground, the Germans struck on January 13. Cotten and his men were ordered to hold static positions and stop any enemy movement south. “We could only move a few feet and empty a few rounds,” he explained. “We always had gunfire going on.”

The Germans attacked night and day, and one night assaulted through the town’s cemetery as flares lit the darkness. Cotten commanded only three tanks, his other two having been loaned to another unit. He kept two on the line while the third brought up ammunition and supplies, since the tanks burned through their ammunition so quickly.

While Cotton’s 37mm cannon could not penetrate thick enemy armor, it worked against trucks and half-tracks. “We shot at everything that moved,” he said. He spent his mornings on foot, visiting his tankers, setting their positions, and making sure they were in the fight. To keep warm, he wore two pairs of socks under his wet boots.

Cotten is Evacuated

During the fighting, Cotten stopped his tank and leaped off the front to go check with his company commander. As he eyed where he was about to land, he heard the distinct “flip-flip-flip” sound of an incoming 81mm mortar round. It landed in front of him as he hit the ground but, luckily for him, failed to explode. He immediately jumped back into his tank. “That was the most scared I ever was,” he said. “I thought I was dead.”

Cotten was not so lucky on the second day of the battle, January 14. He was standing between two tanks when an enemy shell exploded, tearing shrapnel into his left knee and right arm. He went down, bleeding badly, but a medic showed up, bandaged his knee and arm, and gave him a shot of morphine. The medic then had Cotten remove his boots, revealing two frozen feet, with white and dark spots, and his toenails falling off. He was immediately evacuated to the 136th General Hospital in Dijon, France.

From the moment Cotten was put on a stretcher, his feet didn’t touch the ground for 14 days. In the hospital, doctors kept his feet elevated and outside the covers. They did not try to rub any ointments or lotions on them. An orderly stood by his bed, Cotten recalled, “to keep me from moving around or going to the bathroom, or eating, or crying.”

He eventually lost toenails from his right foot, and his left foot turned dark when the blood stopped flowing. The doctors talked about amputating his right foot. “I was scared to death,” he admitted, but the operation never happened. They did, however, sew up his shrapnel wounds.

The doctors also discussed sending Cotten back to the States, but one day they allowed him to walk. “I could go eat and go to the bathroom,” he recalled. He improved well enough after six weeks to return to his unit. “I can’t say enough about how they treated frostbite,” he said. “They took such good care of me.”

By the time Cotten returned to the 14th Armored, its tanks were roaring toward the Rhine River. The river had already been crossed by elements of Lt. Gen. Courtney Hodges’ First Army when they captured the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen on March 7; the bridge collapsed 10 days later, but not before thousands of Americans and their equipment made it across.

Swapping an M5 Stuart for an Easy Eight

Upon his return, Cotten received an M4A3E8 W HVSS Sherman tank—better known as an “Easy Eight”—with a wide-track horizontal volute spring suspension and a high-velocity 76mm cannon—quite an upgrade from the old Stuart 37mm “pop gun.” Also, the Sherman fired high-explosive (HE) and armor-piercing (AP) rounds.

“The [M5] Stuart had armor piecing [rounds], but it was small,” said Cotten. “In the Sherman, we used a little HE if we were shooting at troops, and we used machine guns.” To protect the tank from antitank weapons, ordnance men welded scaffolding on the tank’s sides on which to stack sandbags.

With the Ludendorff Bridge down, the 14th raced night and day to reach Worms to cross a repaired bridge over the Rhine, constructed for Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Third Army.

One night, Cotten’s tanks were moving in a convoy through the pitch darkness when he leaned out of his turret, trying to keep an eye on the tank in front of him. Suddenly, the lead tank stopped and Cotten’s tank slammed into it, throwing him down the front of his tank and knocking him against the equipment strapped to the hull.

“I bled like a stuck pig,” said Cotten. “It tore up my clothes.” He climbed back into the turret and acted more cautiously for the rest of the trip.

The division reached the crossing site at Worms at the end of March and vehicles began crossing a repaired railroad bridge. Cotten got three of his tanks across the bridge before it collapsed. Combat engineers, however, were building a pontoon bridge upriver. Cotten watched as they stretched cables across the river, put pontoons into the water, and treads across the pontoons. “They did a tremendous job,” he recalled.

On April 1, Cotten crossed the river, but the tanks could only cross one at a time. Cotten led the way, walking out front, guiding the driver. Each pontoon sank a few inches as the tank slowly rolled over it.

“I was so happy when we got all five tanks to the other side,” he said. Once on the east bank, Cotten found himself under fire. The war was back on—but there were signs that it might be over soon.

While the tankers bypassed cities like Mannheim, they drove through small towns where white sheets billowed from second-story homes and civilians readily surrendered.

A Shaky Promotion

As Company D headed into the town of Lohr the next day, the Germans knocked out several American tanks with Panzerfausts. A German also shot one of Cotten’s fellow platoon sergeants, Willie Duffett, in the head while he stood in his turret. “I had to look at him with his brain hanging out. It bothered me,” he said with considerable understatement.

While a company was authorized to have five noncommissioned officers, Duffet’s death brought Company D’s down to two. Lieutenant Travis Coxe, who had taken over command of D Company, promoted Cotten to company first sergeant.

Cotten reported to his company commander and asked, “Where do I put my gear?” Coxe asked him where his equipment was, and Cotten told him it was still in his tank. “That’s where you’ll keep it. Get back in your tank. You’re the platoon leader, we don’t have any officers.” Nothing had changed for Cotten, except he received a bit more money.

The promotion did not start off well. When the company crossed its initial point (IP), P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers peeled out the sky and opened fire on the advancing tanks. “We jumped the gun and got ahead of the IP,” said Cotten. He watched the aircraft attack, then ordered his driver to pull off to the right while he reported that the Air Force was attacking his men.

Later, Cotten was standing outside his tank when he came under enemy fire. He dove into a ditch and looked over to see Major Lann next to him. “We meet again,” Cotten told him, adding that he was getting ready to move out. Lann simply replied, “I’m going!” and charged out. “He was a tough guy,” admitted Cotten.

After the fight, Cotton saw the effects of German fire, and possible divine intervention, on one of his men. Tanker Lloyd Burnett caught a bullet in the chest, but fortunately his pocket Bible stopped it, but left Burnett’s entire chest bruised black and blue.

As the tankers continued pushing east, Cotten received a strange call from the ordnance department. “Hey,” a man said into Cotten’s headset as men laughed in the background, “we got one of your tanks back here.” One of his less aggressive tank commanders had gotten lost and conveniently ended up in the rear. The ordnance men quickly sent the stray back to Cotten.

While Cotten got that tanker back, one of his sergeants deserted. “He was a softy,” Cotten recalled, “a mama’s boy.” Military policemen found the sergeant and brought him back to the company where he was charged with desertion in the face of the enemy and court-martialed.

Attacked at Night After Occupying Fürth

As the Third Reich crumbled, the 14th Armored Division approached Fürth, a suburb of Nuremburg, which the Germans still held. As the company approached the town, an American tank from the 10th Armored Division fired on them. Word quickly spread that it had been captured by the Germans, so the tankers brought it under fire and destroyed it.

The company occupied Fürth and the men bedded down. That night, retreating Germans attacked Cotten’s men. By morning they had disengaged, but nine of his men were reported missing. Cotten hopped in a jeep to find them. First, he came across a tanker walking, falling, and getting back up with a large hole in his chest. He recognized him as Oscar Mauser, who had caught a hand grenade in the chest. “He was breathing through the chest and making bad sounds,” Cotten remembered. He quickly wrapped Mauser in a raincoat, carefully loaded him onto the jeep, and rushed him to an aid station.

Returning to the area, Cotten spotted a German boy who led him to a fresh grave in a ditch with an American helmet perched on a rifle. Cotten removed the helmet and found the soldier’s name and serial number in the liner. It belonged to Steve Gavurnik. Cotten reported the name of his dead friend.

Next, the boy led Cotten to a barn. Cotten entered and climbed a ladder to the loft, where he found another tanker, John Healy. His abdomen had been opened by a glancing bullet and his intestines exposed.

“He was bleeding like crazy and crying,” remembered Cotten, but Healy said he was happy to see him. The Germans had captured Healy after he was wounded, placed him on a stretcher, and had other prisoners carry him. When American fighter planes strafed their column, everyone scattered, except Healy, who was left in the middle of the road. The Germans, considering him a liability, stuck him in the loft.

Cotten quickly gave Healy a shot of morphine in each arm, but he could not safely get him out of the loft. He raced from the barn and returned with stretcher bearers, who carefully strapped Healy onto a stretcher and lowered him with ropes and placed him into a jeep, while Healy shouted, “Hurry!”

Cotten kept his distance while the stretcher bearers did their job. “I couldn’t stand it,” he said about seeing his friend in so much pain, but before the jeep pulled away, he went over to say goodbye. Healy told him the last six missing men had all been taken prisoner. Then the jeep departed. “I didn’t think I would ever see him alive again.”

Getting Barked at by Old Blood and Guts

With his nine missing men accounted for—one dead, two wounded, and six captured—Cotten got back in his tank, but the killing wasn’t over. Another tanker, Mike Rusnak, was driving his tank along the edge of some woods when a German antitank gun took off his head and ripped off his gunner’s legs. The next morning Cotten located Rusnak’s tank and pulled the body out. “He was the best tank driver,” Cotten recalled. “He was the most liked guy in the company.”

On April 6, 1945, the 14th Armored arrived at the Hammelburg POW camp, officially known as Stalag XIII-C. General Patton had tried to liberate it in late March, in part to rescue his son-in-law, Lt. Col. John Waters, but the mission had failed.

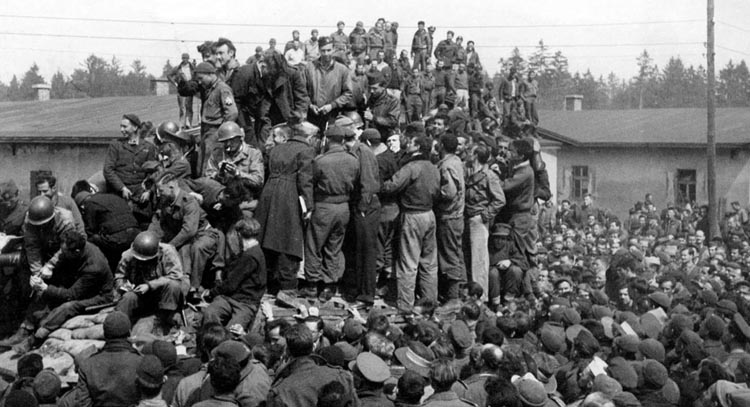

There was no failure for the 14th. At the approach of the Sherman tanks, German sentries quickly abandoned their posts and surrendered. Tankers either barreled through the camp’s gates or yanked them down using ropes attached to their tanks. Ecstatic American, French, and British soldiers, as well as imprisoned civilians, swarmed the tankers in celebration.

One of the first people to greet Cotten was Steve Gavurnik, the soldier he had reported as dead in Fürth. He hugged a shocked Cotten and told him he was happy to see him. “Hell, I’m doubly glad to see you,” Cotten responded, “because you’ve been killed in action!”

Gavurnik explained that the man in the grave was actually Lowell Dean Carlson, whom he last saw standing in the street, firing an M-3 submachine gun—a “grease gun”—before he went down fighting. Cotten reported Gavurnik’s survival to Coxe.

Cotten’s tank soon pulled onto the autobahn, Germany’s superhighway, and cruised unimpeded. “It had lanes all over the place with walls and cuts in the road,” he said. It led east through the mountains and across the Danube River. No more ambushes awaited the Americans; the war was at last winding down.

When Cotten’s tanks ran low on gas, he pulled them into some woods to await refueling. As he and his men waited, Cotten spotted a jeep with large metal flags headed his way. A tall general got out of the jeep wearing a leather jacket, baggy horse-riding pants tucked into his boots, and an ivory-handled pistol on his hip. Cotten was looking at General George S. Patton, Jr.

“Patton was not an attractive man,” recalled Cotten. His mouth was filled with big, wide, stained teeth, and his lips and face were splotched and cracked. Cotten snapped a salute.

“What the hell are you doing stopped?” Patton demanded of Cotten. “Why aren’t you moving?”

Cotten explained that two of his tanks were out of fuel. “Why don’t you get the other two moving?” Patton shouted. “Get moving as soon as you can,” the general added, “and take off those sandbags.” A few curse words emphasized Patton’s sense of urgency. Cotten saluted again and the general departed.

After Patton left, Lieutenant Coxe asked over the radio who had spoken to Patton. Cotten admitted it was him. “You did pretty good,” Coxe told him, “I think he sanctioned the sandbags, but he wanted you to move out.” “Well, we ran out of gas,” Cotten responded.

“Liberators”: The Origin of the Name

Once refueled, Cotten and his comrades pushed east. They knew there was another camp down the road. On April 29, the tankers reached Moosburg prison camp (Stalag VII-A) and tore down the camp’s fences. Again, a captured tanker from Cotten’s company, Tom Manley from Chicago, ran up and greeted him.

All the other missing 14th Armored tankers were also in the camp. They were told to either get back to their units or to the hospital. Medical personnel soon arrived to take care of the worst off. The division continued east to Austria, where the locals acted friendly toward the Americans. For liberating the two camps, and numerous others, the division adopted the title “Liberators.” Approximately 200,000 Allied prisoners of war were liberated by the 14th Armored Division.

Cotten and his men continued their charge east. In early May they occupied a German kaserne along the Inn River near the Czech border. As Cotten and his comrades enjoyed the time off the line, two MPs showed up with the sergeant who had deserted and turned him over to the company. Cotten put a guard on the man and put him to work digging foxholes.

One day, Cotten was working on a firing pin inside his turret when Lann, now a lieutenant colonel, poked his head in and told him, “The war’s over.” Cotten jumped out of his hatch and hugged his commander. It was May 8, 1945. Germany had surrendered.

With the war in Europe finally over but still raging in the Pacific, the division’s longest serving men were allowed to return to the United States for Pacific training. Cotten was part of the first contingent to go home.

He and two other soldiers took a jeep to Linz, where they packed with nine other soldiers onto a train with 30-and-8 boxcars that had no seats or windows. “We thought we were going to fly to France,” said Cotten. The slow-moving train took five days to reach Le Havre, France.

Cotten and the other men marched off the train at Camp Lucky Strike, one of the departure camps, where they waited for transport home.

Cotten Heads for Home

A tanker named Delgardo offered to take Cotten into Paris to sell booty and war trophies that he had collected. The two took a half-track into the City of Lights where Delgardo sold everything and split the profits with Cotten. They made it back to camp in time for Cotten to board a Liberty ship headed for Boston, Massachusetts.

A Liberty Ship could carry 400 men. “It was not the Queen Mary,” said Cotten. Cots were stacked six high. The same meal—stew—was served twice a day. Halfway through the journey, the propeller lost a blade and the ship circled for three days before a repair ship arrived.

Many men got seasick on the voyage. “Usually the guy who got sick was on the top bunk,” recalled Cotten. “We had one man detailed to clean up the mess every day.”

While in transit, the war in the Pacific ended. Cotten’s Liberty ship finally arrived in Boston, and the men debarked to Camp Devens. There, Cotten ate his best meal of the war: “Steak, ice cream, and milk. I hadn’t had ice cream in two years.”

From Devens, Cotton was put in charge of soldiers on a train bound for Fort Sam Houston, Texas. During the slow trip south, the train’s kitchen ran out of bread. Cotten paid for bread for everyone out of his own pocket at towns along the way. As the train neared its destination, two men asked Cotten if they could hop off to visit their nearby homes. Cotten agreed but took down their names, telling them to be at the fort when the train arrived. When the train pulled into the fort, the two men were the first to greet Cotten. “They were glad to be off that list,” he said, for they could have been charged with being AWOL.

There were also recruiters, telling the men they would get 90 days leave if they reenlisted. “However, if you’d like to sign up now, you can.” Cotten wasn’t sure if he wanted to stay in the Army, so he decided to go home to return to his railroad job.

Cotten bought a car and headed to Waco. He went to his sister’s place and kissed his now three-year-old daughter, Marty. He discovered that his wife had strayed while he was at war and his oldest sister Ethel had taken custody of Marty.

Cotten also discovered that his old railroad job had moved to Kansas, so he reenlisted and soon shipped out to South Korea where he worked for a year at the port of Inchon. While there, he divorced his wife, but when his mother died, he took emergency leave and returned to the United States, where he became an ROTC Master Sergeant at Bowling Green State University in Kentucky.

When the Korean War broke out on June 25, 1950, he returned to the country to fight as an officer. In 1959, he was assigned to Fort Knox. There Cotten met Mary Ann Bewley and married her. They had two children, Cynthia in 1965 and Eric in 1967.

He remained in the Army and retired with the rank of major on January 31, 1963. He then worked for 24 years at the Texas Department of Transportation, serving in several positions and retiring as an internal review auditor.

Reconnecting After the War

The war never left Cotten. When stationed in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1965, he took Mary Ann to Hagenau, where they saw a knocked-out tank from his unit. “Twenty years later, and it was still there!” he recalled. Mary Ann also told him that her uncle, Stanley Spalding, had been killed while serving as a reconnaissance scout leading Cotten’s tanks to Hatten. They visited his grave at Epinal, France.

Cotten eventually connected with his fellow tankers. At a division reunion, he hugged John Healy, the wounded tanker in the barn loft, who told Cotten that he had saved his life. Cotten also learned that his mentor, Staff Sgt. Pennington P. Smith, had survived his head wound, was promoted to lieutenant, and had the honor of returning the division’s colors and records back to the United States. Cotton caught up with him at a reunion, and as he remembered it, “We had a nice L-O-N-G, friendly conversation.”

Cotten also met with Mike Rusnak’s family at another reunion. “That was a sad day.” He learned that Oscar Mauser, the soldier with the chest wound, made it home to Louisville, Kentucky, but had later died in an automobile accident.

Like many men of his generation, Cotton credited his comrades for his unit’s success. He always worked with other tankers and armored infantrymen in accomplishing their missions. (He was also uncomfortable with his name appearing so often in this article, wanting to give more credit to his men.)

Looking back at his service in 2019, Cotten had no regrets, although the war sometimes came back to him in his dreams. He started off poor, but the Army gave him a vocation and a career. At 95 years of age, he and Mary Ann are back in Waco, Texas, where their children often visit. “I lived a good life before,” he reminisced, “and I’ve had a hell of a great life.”